No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

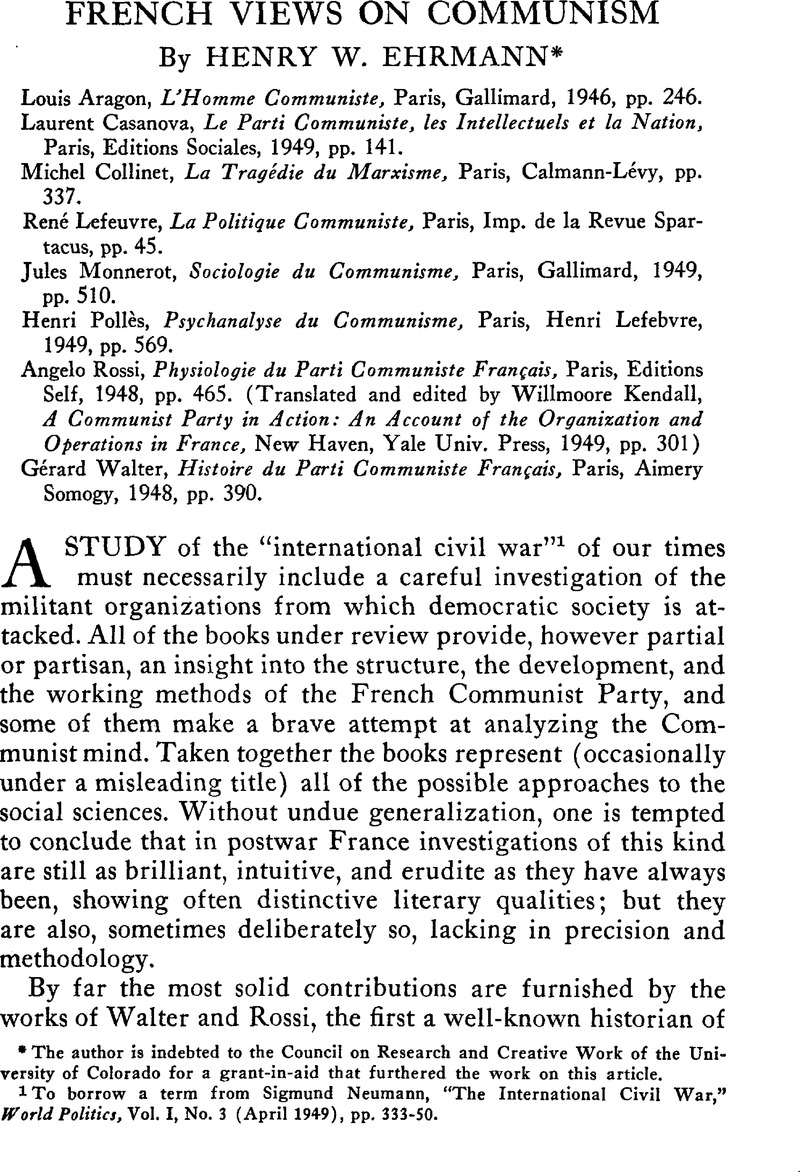

French Views on Communism

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 July 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Trustees of Princeton University 1950

References

1 To borrow a term from Neumann, Sigmund, “The International Civil War,” World Politic, Vol. I, No. 3 (April 1949), pp. 333–50.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 La Naissance du Fascisme: L'ltalie de 1918 à 1922, Paris, Gallimard, 1938, tr. by P. and Wait, D. as The Rise of Italian Fascism, 1918–1922, London, Methuen, 1938.Google Scholar

3 “The Record of French Communism,” The Economist, CLVI, No. 5519 (June 4, 1949), 1047.

4 Pollès, p. 56.

5 Les Faits Sociaux ne sont pas des choses, Paris, Gallimard, 1946.

6 The faith in the “socialist potentialities” of the United States seems to be quite widespread among certain European socialists. See, e.g., Laurat, Lucien, Déchéance de I'Europe: Capitalisme et Socialisme devant I'héritage de la guerre, Paris, Aimery Somogy, 1948Google Scholar, and various articles in La Revue Socialiste, the official theoretical organ of the French Socialist Party.

7 For a good re-evaluation of the “Popular Front” strategy as sanctioned by the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International see McKenzie, Kermit E., “The Soviet Union, the Comintern and World Revolution: 1935,” Political Science Quarterly, LXV, No. 2 (June 1950), 214–37.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

8 For example: Most of Casanova's brochure is devoted to a stern refutation of “deviations” of various kinds on the part of Communist intellectuals. He is constantly preoccupied with possible sympathies for Tito.

9 Compare, e.g., Aragon's glorification of the “communist” miner's movement, p. 47, and of the student manifestations in the Latin Quarter, p. 137, with the account of the same episodes as given by Rossi, p. 411 and p. 48.

10 Monnerot, p. 18 and passim; Pollès, p. 167 et seq.

11 Rossi, p. 74.

12 Thomson, David, Democracy in France: The Third Republic, New York, Oxford Univ. Press, 1946, p. 52.Google Scholar

13 Collinet, pp. 283–84.

14 See, e.g., Casanova, pp. 16–18.

15 Ibid., p. 65.

16 Aragon, pp. 226–27.

17 Ibid., pp. 232, 236.

18 Ibid., p. 32; very revealing to this point also Monnerot, p. 292.

18 Aragon, p. 133; interesting details on Vaillant-Coturier in Walter, pp. 72–76. Walter's book in general excels in portraits of Communist leaders, especially of the early period.

20 Fromm, Eric, Escape from Freedom, New York, Farrer & Rinehart, 1941 p. 175.Google Scholar

21 A suggestion concerning the role to be attributed to the Catholic faith of the French (and Italian) worker is contained in an article by Louzon, R., “La répétition générale et le drame de demain,” La Revolution Proletarienne, XIX (1950), 3–195.Google Scholar

22 Cf. Blum, Léon, For all Mankind, tr. by Pickles, W., New York, Viking Press, 1946, p. 116Google Scholar; Rossi, p. 446; and Lefeuvre, pp. 40–42.

23 Laski, Harold, Communism, New York, Holt, 1927, p. 246.Google Scholar The remarkable two concluding chapters of this small volume deserve close restudy.