1. Introduction

The Liberal International Order (LIO) established in the aftermath of WWII is a set of international rule-based relationships founded on political liberalism, economic liberalism, as well as liberal internationalism.Footnote 1 It builds on principles such as open markets, security cooperation, and liberal democracy. These are circumscribed by legal principles such as the (international) rule of law and human rights. Liberal internationalism involves international cooperation through multilateral institutions such as the international organizations forming part of the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation (WTO).Footnote 2

The intergovernmentalism promulgated by the LIO lies between two extremes: the complete absence of international organized collaboration, on the one side, and the desire for a world government, on the other.Footnote 3 International bodies – and overall governance by international organizations – were also developed within a dialectic relationship between ‘nationalism’ and ‘internationalism’.Footnote 4 Nationalism expresses the view that international institutions should be serving the interests of States; internationalism suggests instead that the purpose of international institutions is eventually to serve the global public good.Footnote 5 In the post-WWII international order, international institutions of the economic sphere became vehicles for the liberalization of cross-border trade and investment; the dialectic seemed to have settled in favour of the international – at least when it came to economic matters.

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, there has been a relative decline in economic globalization. Global trade has been receding since at least 2012,Footnote 6 and global FDI has seen a dip since 2016.Footnote 7 The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated these trends.Footnote 8 This development has been described as ‘de-globalization’,Footnote 9 or ‘slowbalization’.Footnote 10

Overall, faith in the post-WWII LIO of international institutions is diminishing.Footnote 11 This is particularly the case with the institutions of the international economic orderFootnote 12 – especially international investment arbitration – that had given shape to the internationalism of the post-WWII international order.Footnote 13 We observe, as a result, a trend towards institutional and legal deglobalization tooFootnote 14 – or a process that we identify as ‘domestication’ of IEL. We understand domestication as a process of development of domestic rules instead of, or sometimes in parallel to the rules of international (economic) law.Footnote 15 States have a sovereign right to regulate the entry and establishment of foreign investment within their borders.Footnote 16 Foreign trade and investment have a domestic life too – which remains largely understudied.Footnote 17 Borrowing the concept of an ‘ecosystem’ from the field of ecology, we compare the diverse components of domestic rules regarding foreign trade and investment to the different biotic and abiotic components of an ecosystem. What results is a ‘foreign investment ecosystem’.Footnote 18 The foreign investment ecosystem is currently growing in the process of domestication. There are three main types of domestic instruments and institutions regulating foreign investment: Domestic Investment Laws;Footnote 19 Investment Screening Mechanisms;Footnote 20 and Investment Promotion Agencies.Footnote 21 There are also non-investment specific laws relevant to cross-border trade and investment such as property laws and arbitration laws. Such laws co-exist with instruments of International Economic Law such as Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and International Investment Agreements (IIAs).Footnote 22 This article and special issue focus on the relationship between Domestic Investment Laws and IEL in the contemporary environment of contestation of economic globalization.

The domestication of IEL seems to be challenging the assumptions of the post-WWII international order. This article examines the ways in which the foundations of the LIO may be seen to be changing with the transition from international to domestic rules for the regulation, control, and/or promotion of cross-border trade and investment. The article is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the origins and relationship between the LIO and contemporary international law. It then explores the process of ‘domestication’ of IEL. Section 3 provides a typology of domestic laws relating to foreign investment in the broader ‘ecosystem’ of domestic investment law; the main focus is Domestic Investment Laws. Section 4 concludes and outlines the special issue.

2. From Domestic to International in International Economic Law

The present section discusses the origins of both international law and the LIO, as well as conceptualizes the relationship between contemporary international law and the LIO. It finally discusses the process of what is identified in the article as the ‘domestication’ of IEL.

2.1 International Law and the Liberal International Order: Origins and Crises

The twentieth century was marked by the Great Depression and two world wars. A new system was envisaged approximately 75 years ago to avert a repeat of the first half of the twentieth century's major man-made disasters. This is referred to today as the LIO. The LIO is a system based on rules that are applied equally to all countries and encourage each nation to be democratic and operate an open economy. It is a global system in the sense that all states are encouraged to join and adhere to the rules – even if some decide not to join or adhere to them. It is also a system that promotes order with subscribing countries bearing obligations to respect each other's borders and seek peaceful resolution of their differences. International institutions were established to serve as an aspirational blueprint for what became known as the liberal world order.Footnote 23

While these institutions laid the groundwork for the liberal world order, the US was ultimately responsible for its shaping and development after its victory in WWII and subsequent economic boom. The US attributed its success to democracy and free markets and urged other countries to improve their democratic institutions and develop economies that were open to trade and investment.Footnote 24 While entry into the LIO remains voluntary, exiting or refusing to engage with the institutions of the LIO is not a realistic option for most states.Footnote 25 The liberal economic model achieved near-hegemony – even though countries implemented some of the central tenets of the LIO, such as capitalism, differently. The majority of states have shifted to market-based economic management and are integrated into the global economic system.Footnote 26

IEL was shaped as a separate discipline of international law in an era of LIO dominance and has largely accommodated the freedom of movement of goods and capital.Footnote 27 This explicit or implied ideological dominance of LIO, as well as the legitimacy of this order and the international law it gave rise to, has receded gradually due to three interrelated developments: the rise of state capitalism as an opposing ideological paradigm, the crisis of international trade law, and the backlash against international investment law and arbitration.

‘State capitalism’ as a political and economic system puts LIO to the test.Footnote 28 State capitalism can be broadly defined as an economic system whereby the State plays an active role in business and commercial activity – through State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) or otherwise.Footnote 29 State capitalism has exited the realm of the state and become a global paradigm of economic organization. SOEs such as Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) and other government investors have started operating internationally and exercising significant economic influence across borders.Footnote 30 State capitalism is reshaping the foundations of international investment law,Footnote 31 and raises, among others, issues relating to the protection of sovereign investments under IIAs, and posing thus potential challenges to the system of investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS).Footnote 32

The Doha Development Round has largely come to a deadlock. The main success in the multilateral negotiations since the establishment of the WTO has been the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) and the agreement on export subsidies in agriculture.Footnote 33 The ‘Geneva Package’ adopted during the 12th Ministerial Conference on 17 June 2022, including among others a historic deal on fisheries subsidies, has been celebrated as a big success of multilateralism.Footnote 34 Still, the crown jewel of the WTO, i.e. the dispute settlement mechanism under the Dispute Settlement Understanding, remains under severe criticism. Washington has frequently criticized the Appellate Body's (AB) operation, claiming that it ruled unfavourably against the US in trade disputes due to ‘judicial overreach’. In recent years, the US has obstructed new appointments to the AB. This has halted the appeals process, effectively shutting down the mechanism for resolving disputes.Footnote 35

The ‘backlash’ against international investment law and its institutions is now commonplace and a symptom of the overall loss of faith in the institutions of global capitalism.Footnote 36 The backlash as well as the willingness to reform international investment law has been expressed by governments and other stakeholders in both the South and the North.Footnote 37 This shift could have far-reaching implications for the regime of foreign investment. The current crisis is acting as a catalyst to long-overdue change.

2.2 International Economic Law: Towards Domestication

In the immediate post-war years, there was a heavy reliance on domestic laws for the regulation of cross-border economic activity. The new states of the post-colonial world in Asia and Africa started developing domestic investment laws upon independence. This also attracted academic interest in the field during the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 38 Some of the first studies focusing on domestic investment law were carried out by the United Nations regional commissions for AsiaFootnote 39 and Africa.Footnote 40 This gave rise to a series of studies focussed on laws in other economic groupings and jurisdictions.Footnote 41 These studies highlighted the different approaches adopted by states and focused among other things also on constitutional law, admission requirements, and guarantees against expropriation.

International law was thus less relevant for the regulation of cross-border trade until the middle of the 20th century. Foreign trade operated mostly with the unilateral opening of domestic borders and was supported by a series of Treaties of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation (FCN).Footnote 42 FCN Treaties were concluded bilaterally (usually) between Western States and included both trade and investment provisions. Separate international investment agreements started slowly being developed when decolonization of the South was well underway.Footnote 43 Specialized bilateral investment treaties started replacing FCN Treaties for investment and investor protection. International law largely replaced domestic law as the dominant system for cross-border trade and investment protection in the second half of the twentieth century.

It was the rise of LIO and economic globalization that led to the increasing adoption of international trade and investment agreements. The LIO signaled a shift from domestic to international; an increase in the conclusion of international investment treaties as well as a reduction in nationalization of foreign property. Academic interest in national investment laws dropped as well during the same time.Footnote 44 The World Bank published in 1992 a study of existing instruments focussing on the admission, treatment, expropriation, and dispute settlement sections of 48 developing country investment codes.Footnote 45 Since then, developing countries adopted some of the guidelines put forward by the World Bank study.Footnote 46 Developing countries often incorporated, for example, international arbitration into their domestic laws responding to the labelling of arbitration as ‘international best practice’ by the World Bank.Footnote 47

The crises of IEL discussed in the previous section are driving countries again towards the adoption of robust domestic frameworks for the management of foreign economic flows. IEL generally recognizes the regulation of FDI as a sovereign right of states. There are no general international obligations to allow market access to foreign investors and admit foreign investments into the host state. The standard BIT does not grant a right of admission to a foreign investor or any other type of pre-entry protection for foreign investment; BITs generally defer to the requirements of the host states.Footnote 48 The same is true for the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (ICSID Convention), which includes no rules on pre-entry protection for foreign investments.

‘Domestication’ in IEL may be understood as a process of devolution from the international to the domestic, i.e. a transition from the use of international to domestic legal instruments for the regulation of cross-border trade and investment flows. States around the world have been resorting again in more recent years ever more frequently to domestic means to regulate foreign trade, investment, and finance. Policies aimed at attracting FDI have explicitly focused on attempts to improve the host nations’ broader enabling environment.Footnote 49 An increasing number of nations are using domestic law to govern the entry and development of foreign investments, give assurances for the repatriation of profits, and resolve investment disputes.Footnote 50 Tax breaks are often provided too.Footnote 51 Some governments, for example, have used very low corporate tax rates to entice foreign corporations – as well as to induce domestic enterprises to stay. Other policies have included preferential tariff regimes, reduced red tape, increased infrastructure investment, and educational initiatives. These domestic policies are often adopted with a view to replacing international legal instruments. South Africa, for example, decided to terminate or not to renew the BITs concluded after 1994. The Protection of Investment Act (PIA) of 2015 aims instead at replacing BITs as the main instrument for FDI regulation.Footnote 52 Other countries enhance their domestic investment legal framework while continuing to pursue international economic agreements.

Overall, these changes may be interpreted as a move from the international to the domestic in IEL. Yet, the interplay between domestic and international in IEL is very complex. Domestic laws can be viewed as a source of international investment law, especially when it comes to investment treaty arbitration claims. Salacuse identifies domestic legal frameworks as one of the three legal layers of international investment that seek to encourage and control foreign investment.Footnote 53 Some scholars see domestic law as a formal source of foreign investment law.Footnote 54 Domestic investment laws may be interpreted as functioning as unilateral acts of states under international law.Footnote 55 Jarrod Hepburn argues that foreign investment laws (FILs) occupy a complicated position in public international law;Footnote 56 for this reason, claims under FILs are neither mere treaty claims nor contract claims. Instead, such claims possess a separate and distinct nature, raising unique questions of general international law – particularly the law of state responsibility and unilateral acts.Footnote 57 Over the last few decades, there has also been an increase in domestic investment law-based international arbitration claims.Footnote 58 Thus, recent studies have focussed on international arbitration resulting from domestic law – with a focus on issues such as consent to ICSID arbitration in domestic investment laws,Footnote 59 and the risk of arbitration in accordance with domestic laws.Footnote 60

Independent of the exact classification of the role of domestic law under international law, the move to domesticate IEL does not generally signify a new era of economic isolationism for states. Instead, it is largely an effort to achieve similar ends of attracting foreign investors using different means while exercising at the same time more control over foreign investment. Thus, the domestication of IEL is not necessarily incompatible with the core values of IEL – that remain the freedom of cross-border movement of goods and capital. However, the domestication process in IEL still challenges the dominant paradigm of the LIO, where trade and investment were to be regulated at the international level by multilateral and other international rules and institutions.

The next section of the article turns to the discussion of laws relating to foreign investment with a focus on Domestic Investment Laws.

3. Laws Relating to Foreign Investment

Laws relating to foreign investment may be specialized, dedicated to investment, or non-specialized; they may include special provisions for foreign investors or may apply to any investor independent of nationality; they may be promoting and facilitating, or controlling foreign investment.Footnote 61 This section of the article discusses Domestic Investment Laws and other laws relating to foreign investment in the broader ‘ecosystem’ of domestic investment law.

3.1 The Legal Ecosystem of Foreign Investment

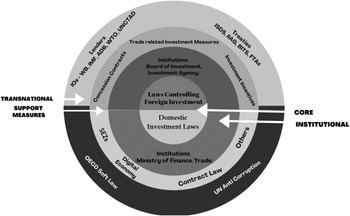

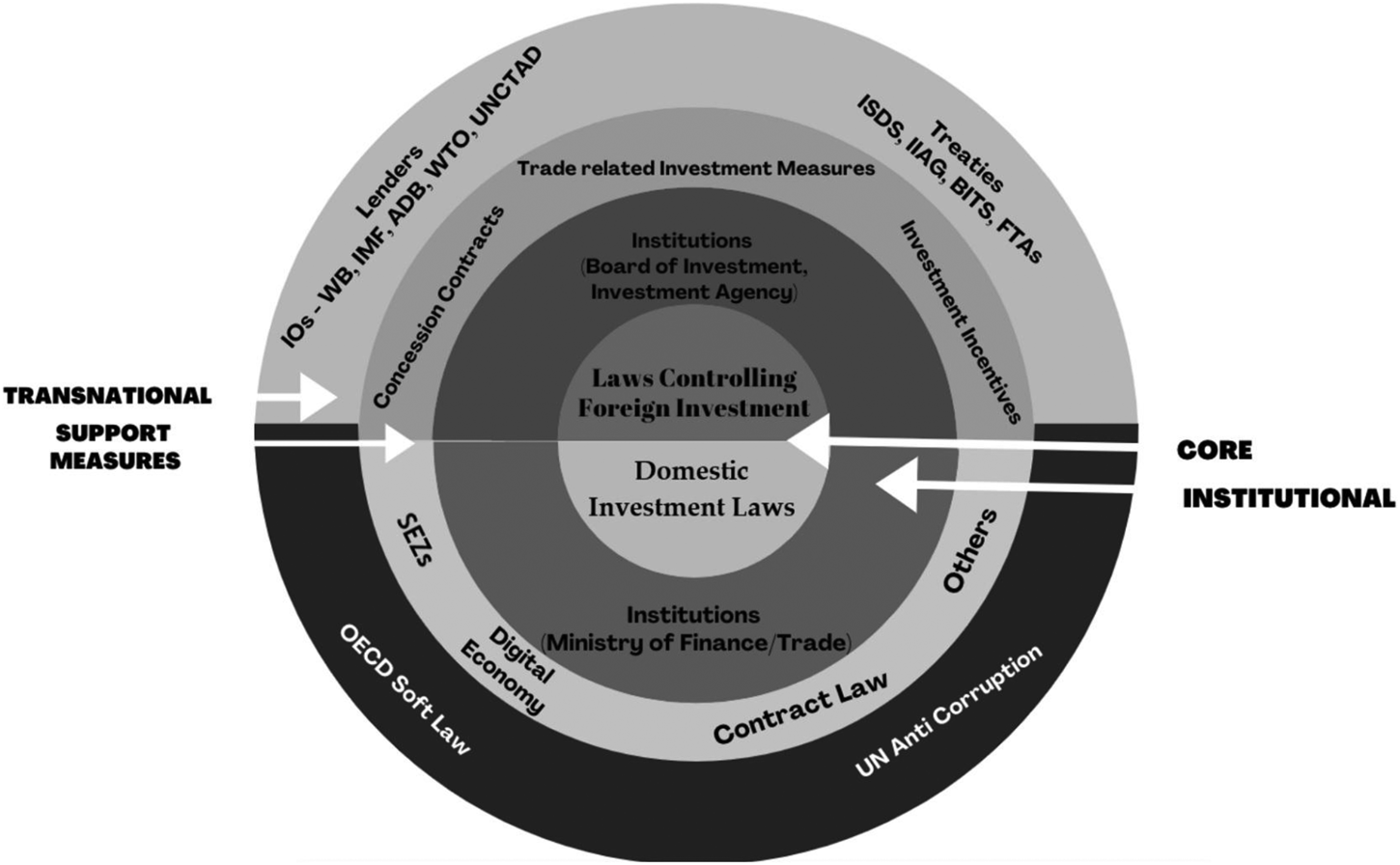

A very broad set of diverse laws may have an impact on foreign investment. A national legislative and regulatory framework pertaining to foreign investment may be understood as forming an ‘ecosystem’ of domestic investment law. An ecosystem is a term from the field of ecology that can usefully be applied to describe the way domestic laws regulate investment.Footnote 62 The legal eco-system on foreign investment (Figure 1) has three distinct features. First, it is a system greater than the sum of its components. Second, any change in one element of the ecosystem impacts the rest of the system. Third, the ecosystem is organized as a hierarchy.

Figure 1. The Legal Ecosystem of Foreign Investment

Source: prepared by the authors.

As shown in Figure 1, the legal ecosystem of foreign investment comprises interactions and relationships between players in the same region or section of the environment. The ecosystem's ‘dynamic elements’ include law firms, law schools, in-house counsel, regulators, and alternative suppliers. Regulations and other external factors are examples of non-living components – and are the focus of the article.

The investment law ecosystem of a jurisdiction may be comprised of legislation that is specialized and specifically addressed to foreign investors; or it may be comprised of more general legislative instruments that may have an impact on foreign investment flows.Footnote 63 Some countries have no laws to regulate investment specifically. Jurisdictions with a more liberal approach to foreign investment often choose not to have laws specifically addressed to prospective investors.Footnote 64 Hong Kong, for example, has no general investment legislation governing the admission of foreign investment.Footnote 65 Hong Kong's laws do not differentiate between domestic and foreign investors; foreign investors are treated like domestic investors and the general competition law applies to them, as well as regulations governing mergers and acquisitions. Jurisdictions with less liberal approaches to FDI have also sometimes followed the same approach.Footnote 66

There are many laws that form part of the broader legal ecosystem but are not always designed specifically to promote and/or facilitate foreign investment. Public procurement and Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) are the two main financing tools that are used to attract private investment, often foreign,Footnote 67 for public projects.Footnote 68 Many countries have used PPP laws as a substitute for or complement to international investment law. The government of Ecuador, for example, famously terminated several BITs based on the findings of a committee tasked with auditing Ecuador's IIAs – the Ecuador Investment Treaties Audit Commission (CAITISA).Footnote 69 At the same time, it introduced a new PPP law with the aim of replacing the international law protection mechanism with a domestic framework.Footnote 70

An often-disregarded category of laws of the broader legal ecosystem of foreign investment are property laws. Many jurisdictions place restrictions on real estate ownership by foreigners; for instance, countries in the Middle East and North Africa Region have traditionally had in place laws limiting the purchase of land by foreign nationals. Latin American countries, on the other side, are often open to foreign investment in real estate and infrastructure sectors, making foreign ownership of land and investment in infrastructure generally possible.Footnote 71 Besides property laws, employment laws will have an impact on foreign investment too. Nationality and residence laws are equally important. Governments have started placing a greater emphasis on these aspects of the domestic investment framework by giving, for example, nationality to foreign investors or adopting ‘golden visa’ schemes to attract foreign investors.Footnote 72 In the digital age, new types of laws are added to the overall foreign investment ecosystem,Footnote 73 amongst which laws governing data – whether commercial or personal.Footnote 74

Laws and institutions pertaining to dispute settlement are also an integral part of the eco-system. National arbitration laws often form part of the factors foreign investors consider when deciding to invest in a foreign jurisdiction. National arbitration laws are often drafted based on an international arbitration law template, such as the UNCITRAL Model Law, with a view to reassuring foreign investors that potential disputes will be adjudicated based on arbitration laws with which they are familiar.Footnote 75

3.2 Domestic Investment Laws

More recently, countries around the world have started adopting specialized investment laws. Laws that control and restrict foreign investment have started becoming popular. Almost all major economies have in place mechanisms to control inward investment flows. One can distinguish between two main types of foreign investment control: outright prohibition and screening.Footnote 76 Some countries – either alongside or without a formal review process – may prohibit foreign investment in certain industries or restrict market access to certain sectors or (the extent of) ownership in certain sectors, such as very often in the natural resource and real estate sectors. For example, Russia does not allow foreign investors and foreign SOEs to gain majority interests in ‘business entities of strategic importance for national defence and state security’ in industries such as defence, oil and gas, and aviation.Footnote 77 France uses the Banque publique d'investissement (Bpifrance) to block takeovers of ‘strategic companies’ in which the government owns shares by using the ‘golden share’ mechanism, as well as further actions such as sanctions imposed by the Minister for the Economy and Finance.Footnote 78

Amongst foreign control mechanisms, investment screening statutes establishing foreign investment screening mechanisms have become widespread.Footnote 79 Most countries in the West have now established investment screening mechanisms to control investment flows from emerging economies.Footnote 80 The example of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an interagency committee established in 1975 by President Gerald Ford, has often been followed.Footnote 81 Countries from other regions already have a longstanding tradition of controlling foreign investment flows.Footnote 82 Investment screening mechanisms block or limit the entry of foreign investors, generally or for certain sectors, and/or subject them to requirements listed in the law. Protection of national security interests is the main driver behind the establishment of investment screening mechanisms.Footnote 83 Contemporary investment screening laws move beyond national defence and link national security to three additional considerations: the involvement per se of SOEs; protection of critical technologies with a view to keeping a technological edge in today's competitive economy; and the protection of critical infrastructure.Footnote 84

Other legislative frameworks still aim at promoting and/or facilitating foreign investment. Investment promotion and/or facilitation laws aim at achieving their result by providing – organizational, infrastructural, and/or fiscal – incentives for foreign investment in certain sectors.Footnote 85 Tax incentives, for example, have long been used to attract, retain, and expand business. By creating more job opportunities, they in turn have significant local benefits. Nationals will benefit from increased employment and income as a result of more local jobs. More jobs may result in ‘fiscal benefits’ in the form of increased tax income that exceeds growth-induced increases in government expenditures.Footnote 86

Different jurisdictions also have different institutional set ups to manage the domestic investment ecosystem. National authorities must determine the amount of decision-making power that will be transferred to lower levels of government. This decision is determined by the type of FDI incentive methods adopted. Providing the local level of governance with greater leeway, for example, often allows nations to benefit from the detailed knowledge of sectors that local state actors typically possess. Further, investment projects then become more locally accessible. However, this comes with the risk of inciting competitive bidding and other wasteful activities within the jurisdiction.Footnote 87 Some countries establish, instead, Investment Promotion Agencies (IPAs) to proactively promote and facilitate foreign investment in their jurisdiction at the central government level.Footnote 88 Irrespective of where administrative and political responsibility is assigned, it is widely acknowledged that the implementation of FDI incentives should be driven by a set of clearly defined policies conveyed to the appropriate authorities by policymakers. Greater standards of accountability and transparency to the general public provide clarity and allow for generalized support of the investment policies.Footnote 89 On the other side, political pressure and media speculation make the management of incentive schemes more challenging. When FDI incentives are contested in the legislature or the media, it is particularly difficult for public sector managers to negotiate with prospective investors.Footnote 90

The article – as well as broader special issue – focuses on Domestic Investment Laws (DILs) that seek to promote and/or facilitate foreign investment. While different types of laws and institutions in the broader foreign investment ecosystem touch upon investment, DILs may be defined as specialized statutes that seek to promote and regulate (foreign) investment in one single document.Footnote 91 While thematically specialized, DILs apply in the whole jurisdiction of the country that adopts them.Footnote 92

DILs and their recent coming into vogue remain largely understudied.Footnote 93 Developing countries have historically promulgated statutes promoting and facilitating (foreign) investment in one single instrument.Footnote 94 These laws vary significantly in scope and include foreign investment codes, national investment codes, etc. Some countries, while having in place DILs, provide for the same or similar treatment to both domestic and foreign investors.Footnote 95 For example, the South African Protection of Investment Act of 2015 applies to both national and foreign investors.Footnote 96 The statute safeguards national treatment to foreign investors.Footnote 97 Other countries choose instead to adopt DILs that apply exclusively to foreign investors. Countries in the Gulf Region – such as Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates – have traditionally followed this approach. Their foreign investment statutes place restrictions on the participation of foreign investors in certain sectors of the economy, and/or mandate the involvement of nationals in economic activity. Non-nationals are usually allowed to invest in most sectors of the economy provided that they become shareholders in a company that is established according to national law and that they have a local partner that contributes no less than 51% of the capital of the company.Footnote 98 This has recently started changing as more Gulf countries adopt new foreign investment laws lifting some of these restrictions.Footnote 99

Unlike the rules of international investment law, DILs are unilateral laws stipulated at the domestic level, which may extend protection to both domestic and foreign investors.Footnote 100 DILs are introduced with a view to applying domestic law either instead of or in parallel with the instruments of international economic law as a way to attract foreign investment and provide safeguards to foreign investors.

4. Conclusion and Outline of the Special Issue

The focus of this special issue is on the relationship between DILs, as well as other aspects of the domestic legal ecosystem of foreign investment, and IEL. The articles cover a broad range of theoretical issues pertaining to DILs and international investment, as well as more concrete applications of the interplay between these two means of regulating cross-border economic flows.

Jarrod Hepburn in the Article titled ‘The Past, Present and Future of Domestic Investment Laws and International Economic Law’ discusses the history and the future of domestic ‘facilitative’ investment laws. These statutes encourage foreign investment by providing substantive protections to foreign investors as well as consent to international arbitration over investment disputes. The author suggests that while investment treaties perform very similar functions to facilitative investment laws, states have had independent reasons to enact domestic laws alongside the international agreements. The article then argues that investment laws can be characterized either as unilaterally assumed international obligations or as simple domestic laws. The different classification leads to varying consequences. Finally, the article discuses four possible futures for investment laws: contamination, continuation, compromise, and contestation.

In the contribution to this issue titled ‘Domestic Investment Incentives in International Economic Law’, Anastasios Gourgourinis discusses various types of domestic investment incentives and how they are dealt with under the WTO agreements. Investment incentives are often included in domestic investment laws aiming at influencing investment location decisions by creating favourable conditions for foreign investment. The article explains that the WTO agreements set implicit constraints on potentially trade-distorting investment incentives. The author finally claims that this poses limitations to the process of domestication in IEL.

The article by Anna Sands discusses ‘Regulatory Chill and Domestic Law: Mining in the Santurbán Páramo’. The article – deviating from methodological orthodoxy – addresses regulatory chill from the perspective of the state itself. The article fills a gap in the relevant scholarship by providing an analysis of the interplay of domestic laws and institutions in the context of potential investment claims – using a case study of mining in the Santurbán páramo region in Colombia. Colombia had created laws and institutions internalizing international investment rules. The article highlights instead the role of domestic constitutional law in averting regulatory chill. The case study also adds to the discussion of how the contemporary international order may be shifting from international to domestic governance. It does so by stressing that domestic laws and institutions may have diverging priorities, which also determines how the risk of investment claims may be dealt with domestically.

Julien Chaisse's article titled ‘“The Black Pit:” Power and Pitfalls of Digital FDI and Cross-Border Data Flows’ addresses the relationship between international investment and increasing cross-border data flows. It discusses the legal aspects of new data paradigms in the broader framework of globalization and the LIO. The author discusses the interplay between national and international legal regimes, and how the changing nature of the LIO impacts cross-border data flows. The article addresses the lack of overarching international legal and policy frameworks governing cross-border data flows, and puts forward the proposal to update existing international agreements with a view to including digital FDI.

In a contribution titled ‘The Right to Hospitality in International Economic Law’, Georgios Dimitropoulos discusses the ways in which investment law has been shaped in the interaction between national and international rules. While under the LIO, investment protection to foreign investors was supposed to be granted by international law and institutions, current economic de-globalization is giving way to institutional and legal de-globalization. DILs, and other domestic laws relating to foreign investment, are largely playing the role BITs and other IIAs used to perform. This suggests a move away from some of the principles of the LIO. The author provides an explanation for this process based on an alternative political economy for international and domestic law. The cornerstone of this new law and political economy framework is a ‘right to hospitality’, which is reflected in a ‘right to invest’ in IEL.

Kehinde Olaoye and Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah discuss – in a contribution titled ‘Domestic Investment Laws, International Economic Law, and Economic Development’ – how ‘development’ continues to be at the forefront of the interaction between DILs and IEL. The study of over 3000 IIAs and DILs signed in the last 70 years helps the authors identify the ways in which development as a concept has evolved together with the growth of IEL. The authors then break down the history of international investment law in six main phases, and trace the emergence of ‘development’ as a pertinent topic in DILs to the decolonization era. They also look into the interpretation of ‘investment’ by ICSID tribunals, the continued relevance of the New International Economic Order, and the more recent shift to sustainable development in academic debates and practice in IEL.

The article of Xu Qian titled ‘Domestic Investment Laws and State Capitalism’ suggests that state capitalism and the LIO are in a competitive relationship. While IEL during the LIO has generally aimed at reducing the role of the state in the economy, SOEs have more recently increased in size and importance domestically, as well as internationally. The article undertakes an analysis of the principles and of state capitalism with a view to understanding whether domestic laws promoting investment are positive, negative, or neutral to state capitalists.

Tarald Gulseth Berge and Ole Kristian Fauchald, in their contribution titled ‘International Organizations, Technical Assistance, and Domestic Investment Laws’, discuss how international organizations have been trying to shape domestic laws aimed at protecting foreign investment. While the influence of international organizations has been generally assumed to operate though loan conditionalities, the article studies the influence of international organizations on domestic policy through technical assistance. The empirical study presents a cross-sectional mapping of the protection offered by states to foreign investors in DILs, as well as a mapping of the advisory activities of the three main organizations active in the field of technical assistance – the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Bank. The authors find significant variations in the protection offered under DILs, as well as the types of technical assistance offered across international organizations – as well as by the different international organizations over time.

Finally, Pasha Hsieh, in his article on ‘New Investment Rulemaking in Asia: Between Regionalism and Domestication’, provides an analysis of investment rulemaking in the context of new Asian regionalism as well as emerging and evolving national legislation of Southeast Asian states. The author suggests that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) represent Asia's ‘pragmatic incrementalism’ in reforming the investment regime. This is, according to the author, a process that reinforces the relationship between IEL and DILs. Alongside transforming international investment agreements, ASEAN expedited investment and trade in services and established ISDS. The author argues that RCEP further consolidates ASEAN Plus One agreements – despite the exclusion of ISDS. The article then discusses the Asian countries’ recent investment agreements as well as domestic dispute settlement that seems to complement the LIO. The author concludes that the Asian paradigm may provide a model for developing countries and emerging economies, as well as contribute to the broader discussion on global investment reform.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our thanks to our colleagues Tarald Gulseth Berge, Ole Kristian Fauchald, Anastasios Gourgourinis, Jarrod Hepburn, Pasha Hsieh, Susan Karamanian, Kehinde Olaoye, Xu Qian, Anna Sands, and Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah who provided incisive feedback on earlier ideas and drafts. We would also like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided generous and constructive comments on a draft of this article. We are also verry grateful to the editors-in-chief and staff of the World Trade Review for their wonderful communication and support throughout the project. All errors remain ours.