1. Introduction

The World Trade Organization (WTO) struggles to make substantial progress on trade reforms, its Appellate BodyFootnote 1 has been disabled, and multilateral trade rules are eroding. There are at least 20 unresolved WTO disputes that remain in limbo, and that could be ‘Appealed into the void’.Footnote 2 Most recently, the US has announced export controls on high-end semiconductors to China, explicitly citing the need to ‘degrade’ China's technological capacity. The US also recently announced subsidies on electric vehicles made in the US, a clear violation of WTO rules, and rejected WTO panel findings against its invocation of national security to apply aluminum and steel tariffs on its allies. Of course, the US is not the only culprit in this worrisome dynamic. However, it is difficult to see how the rules-based system resists the barrage of rule-breaking, especially when the US, the architect of the present system, is in an ongoing and intensifying trade war with China, the world's largest exporter of goods.

Meanwhile, preferential trade agreements (PTAs) continue to proliferate. Trade under preferences (preferentialism) was envisaged initially as an exception to the most favored nation (MFN) principle at the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)/WTO. Still, WTO members now carry out most of their trade under some form of preferential agreement.

To be clear, this does not mean that most of the world goods trade benefits from preferences. Underscoring the WTO acquis, estimates placed the average trade-weighted preference margin at only 1% in 2008 (WTO, 2011). However, WTO MFN treatment can no longer be considered the assured counterfactual, and the expected welfare added by PTAs increases the lower the probability that WTO treatment remains.

The progressive erosion of WTO rules calls for capitals to reassess the role of PTAs in their trade policy. This article reviews the state of PTAs and addresses their systemic implications in the present context based on the most recent trends. At a time of fraught relations among the trade giants, China, the EU and the US, we pay special attention to the blocs forming around them. Can PTAs replace a fading WTO or at least mitigate the effects it has? How will a trading system based increasingly on PTAs and weak multilateral rules look, and how will nations adapt?

Drawing on updated information on the evolution of PTAs, we make the following assessments:

• After a remarkable advance from the establishment of the GATT in 1948 to 2010, by when PTAs had come to cover most of the world trade, the years since have seen continued, albeit slower, progress in their trade coverage. Still, the role of PTAs has been bolstered because the composition of agreements shifted markedly towards PTAs that are reciprocal, deeper, broader, and more enforceable. Moreover, the new agreements include three mega-regionals and the updated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)/United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), which accounts for a vast share of world trade and gross domestic product (GDP)

• Additional trade covered by PTAs since 2010, marking the end of the global financial crisis (GFC), was overwhelmingly concentrated among countries in Asia or involved an Asian partner. Meanwhile, the trading powers followed different paths, with China especially active in negotiating new PTAs and concluding Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnerships (RCEPs), the EU pursuing a very active program, including deals with large trading partners such as Canada and Japan, and the US standing back entirely from new agreements beyond the renegotion of NAFTA.

• Driven by geopolitics, trade policy uncertainty, and other powerful motives, the proliferation of PTAs is likely to continue, and they will soon cover about two thirds of world trade. However, the world's most important bilateral trade relationships – those between China, the EU, and the US – remain uncovered by PTAs or even partial deals, as negotiations among them have failed or been stalled. The giants are each part of PTAs/mega-regionals in their respective regions, in which they play a dominant role, so as multilateral rules erode, there is is a strong temptation for policy makers to push for ‘friend-shoring’ or ‘near-shoring’. Firms faced with this uncertainty will be inclined to follow and partition their supply chains regionally, implying duplication and inefficiency but not necessarily outright withdrawal from global markets.

• The regional blocs are not cohesive, reflecting divergent economic and security interests among members and between the members and the regional hegemon. Smaller members and the middle powers will be forced into asymmetric deals with the hegemon or try to play off the hegemons with each other or both. This means that the politicization and weaponization of trade relations are likely to increase even within regions

• The worst scenario is the one to which we are heading, where the WTO rules become increasingly eroded, and the regional hegemons eschew deals with each other. The best scenario, presently a low probability but to which policy must aspire, is a revitalized WTO with enforceable rules and deals among the trade giants that specifically address the major issues that divide them.

In the rest of this article, we provide information on the coverage and scope of PTAs, drawing on the latest available data in Section 2. We then discuss some systemic implications of the recent trends in Section 3. In Section 4, we offer some policy observations and conclude.

2. PTA Trends

2.1 Motivations

Before multilateral trade rules were adopted by 30 signatories of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1948 – global rules as we know them did not exist. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, right up to World War 2, London and Paris proclaimed tariffs that applied generally, or only to some, and established imperial preferences, trade rules, and navigation laws that their colonies observed. Great and minor powers struck dozens of commercial treaties or fought trade wars. By today's standards, trade flows were small as a share of output – the commercial treaties of the past were shallow agreements, covering mainly tariffs, quotas, and navigation rights. Dating back to the eighteenth century, an MFN clause was often included. The MFN clause was an invention of commercial treaties of past centuries, the precursor of today's PTA, but it now lies at the core of multilateral trade disciplines. Underscoring the remarkable achievement of the post-war trading system under the GATT/WTO, the MFN clause and its companion, national treatment, now covers 164 countries or territories and 98% of world trade.

Over a long spell following the GATT's establishment, the contracting parties’ focus was on multilateral agreements that reduced tariffs and established global rules, culminating in the creation of the WTO and the expansion of its membership to cover nearly all of the world trade. Over eight GATT Rounds from 1948 to 1994, including the Uruguay Round, which launched the WTO, tariffs were reduced progressively. Since 1990, the world average MFN applied tariffs were cut from over 20% to under 10%, and below 5% in high-income countries.Footnote 3

The rise or, more accurately, the rebirth of preferentialism was a gradual process, one which overlapped with the multilateral trade agenda but eventually came to surpass it as the main preoccupation of WTO members. Today WTO members have some type of PTA – including non-reciprocal arrangements – with an average of 55 partners.Footnote 4 For example, each EU member has reciprocal agreements with 46 non-EU countries, in addition to those with the 26 other EU members, for a total of 72, while the US counts only 19 such reciprocal agreements, and China 37 of which eight are non-reciprocal.

The political economy literature identifies numerous possible motives behind PTAs (Whalley, Reference Whalley1998).Footnote 5 Most relevant to the questions that this article seeks to address are four reasons countries pursue PTAs, each of which is likely to reinforce the present proliferation trend: the cementing of alliances, deep integration, trade policy uncertainty, and competitive liberalization.

Geopolitics has long been recognized as a driver of PTAs. For example, Eichengreen, Mehl, and Chitu (Reference Eichengreen, Mehl and Chitu2021) find, using the pre-World War 1 period as a reference, that defense pacts boost the probability of a bilateral trade agreement by as much as 20%. Other scholars have found a link between trade flows and military alliances (Long and Leeds, Reference Long and Leeds2006). Of course, the EU is, at its origin, an agreement to cement peace between France and Germany, and all US trade agreements are with allies or closely aligned nations. At a time of increasing great power competition, trade deals motivated by alliances and national security will be pursued.

Also relevant to our purpose is that reciprocal PTAs are often more ambitious in scope than WTO disciplines. This feature makes them more attractive as globalization continues to advance (Dadush, Reference Dadush2022). For example, they typically bind tariffs at zero for 90% or more of tariff lines, whereas WTO agreements allow tariffs to be bound at higher levels. They are also increasingly designed to address regulations that impede exchange. This ‘deep integration’ aims to ease the efficient allocation of all resources – capital, labor, and technologies – among the parties. The European Union's single market framework is the most advanced (and quite unique) example of this model.

Increased trade policy uncertainty, especially global uncertainty, associated with eroding multilateral rules and rifts among the world's largest trading nations, encourages countries to cement their most important trading relationships (Constantinescu, Mattoo, and Ruta, Reference Constantinescu, Mattoo and Ruta2019; Handley and Limão, Reference Handley and Limão2022). Meanwhile, the fear of exclusion, or loss of competitiveness, causes third parties to seek similar deals (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg2003).

Our brief account of how PTAs rose (or returned) after a brief interlude of dominant multilateralism is divided into three periods. The first period, 1948 to 2010, ended with the global financial crisis and saw the most rapid advance in PTAs. The second period, from 2011 to 2020, saw a slower advance of trade coverage of PTAs but also a number of changes that, in our view, made them more systemically important. The third period, 2021 onwards, is a forward look based on the latest available data and our reading of the trends.

In describing the evolution of PTAs, we adapt the typology of Frankel, Stein, and Wei (Reference Frankel, Stein and Wei1997), recognizing four main types of agreements: non-reciprocated preferential trade agreements (NR-PTA); free trade agreement (FTA) – a reciprocated granting of preferences compliant with Article 24 conditions; partial free trade agreement (PFTA) – a reciprocated granting of preferences on a part of trade, such as those developing countries grant each other under the Enabling Clause; and a common market (CM) which includes customs unions, agreements which include adoption of a common external tariff, and even deeper agreements which may include free movement of capital and labor, adoption of a common currency, etc. CMs are the deepest type of agreement, followed by FTAs, PFTAs, and NR-PTAs, which are granted and can be withdrawn unilaterally.

2.2 1948–2010: PTAs come to Cover Over 60% of World Trade

The first trade agreement in the GATT-WTO era was the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU) which entered into force in 1949, became inactive in 1955, and was relaunched in 1970. SACU is the post-war world's first customs union.Footnote 6 The European Customs Union, among six founding members, was launched in 1968, almost 20 years after SACU. Until it signed its first FTA with Israel in 1985, followed by the FTA with Canada in 1988, the United States focused its efforts almost exclusively on furthering the multilateral liberalization agenda in the GATT, which was the main driver, and with considerable success.

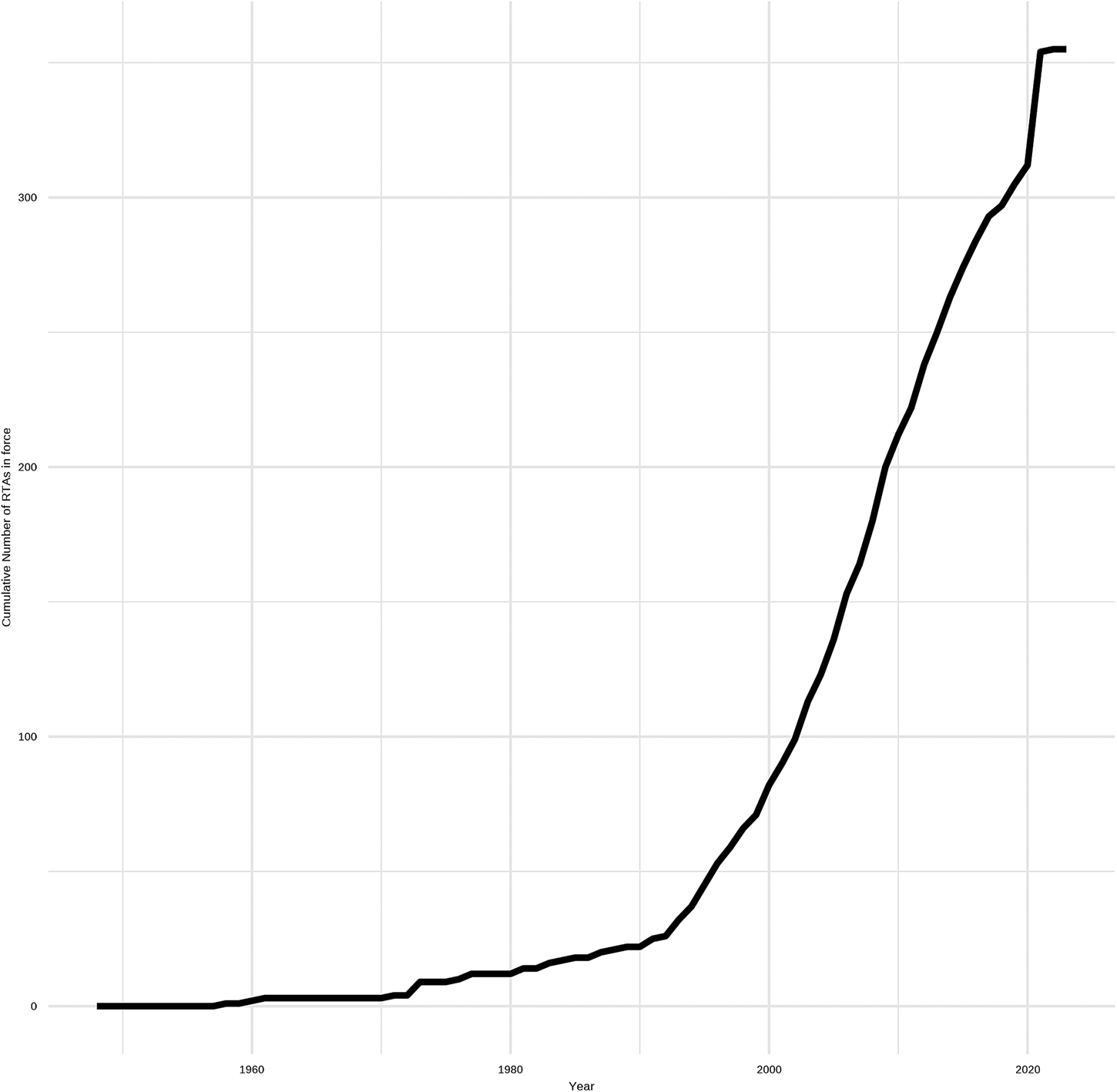

Despite progress in reducing tariffs multilaterally, the trend towards PTAs gradually gathered strength. As Figure 1 shows, a sharp acceleration in the number of agreements notified to the WTO occurred around 1991, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the entry of formerly planned economies into the mainstream of world trade. The rapid increase in the number of agreements persists to this day. Recently, the increase is due to Brexit and new agreements negotiated by the UK,Footnote 7 which replace EU agreements, with third parties and add little to world trade coverage of PTAs.

Figure 1. Evolution of Preferential Trade Agreements

As the UK case illustrates, counting notifications to the WTO is not terribly meaningful since agreements come in various sizes and may not be additional at all in terms of trade coverage. In 1965, with the European Community recently established, the share of world exports covered by preferential trade was 22%. By 2010, it was 60% (Limão, Reference Limão2016). The most consequential PTAs include the progressive expansion of the European Union from six to 28 members and the conclusion of the North American Free Trade Agreement between Canada, Mexico, and the United States in 1994.

To update the estimates of trade covered by PTAs, we first tried to replicate the calculations to 2010, using Limao's method, drawing on the WTO as well as on the NSF-Kellogg Institute Database on Economic Integration Agreements.Footnote 8

That database uses the above-mentioned taxonomy of PTAs between 195 countries for the period 1950–2017.Footnote 9 This NSF-Kellogg database has been used in other subsequent studies (Nguyen and Vaubourg, Reference Nguyen and Vaubourg2021; Díaz-Mora, García-López, and González-Díaz, Reference Díaz-Mora, García-López and González-Díaz2022)

We arrive at 61.7% of exports covered by PTAs in 2010, 1.7 percentage points more than that of Limão (Reference Limão2016). Possible explanations for the small difference are data revisions that caused us to include an agreement not previously reported or caused us to use a different base for world trade.Footnote 10

As discussed, not all trade among the parties of a PTA is covered by the agreement. It is not possible to know exactly how much trade is covered without examining in depth the stipulations of hundreds of agreements. To get around this problem, we adopt the convention of counting all trade among the parties to the agreement whether the agreement covers it or not.Footnote 11

2.3 2011–2020: PTAs Deepen and Widen

In the years following the GFC, trade negotiations lost momentum and only some small agreements were concluded, such as Chile–Viet Nam in 2011 and Australia–Japan in 2014. The conclusion of large preferential agreements occurred only in recent years.

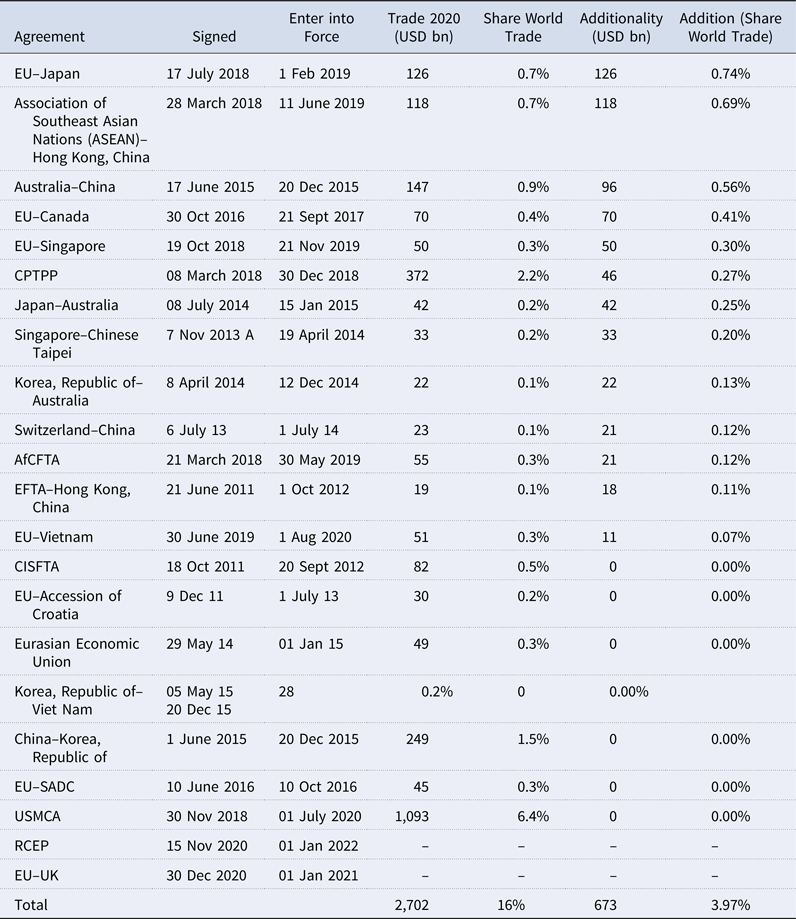

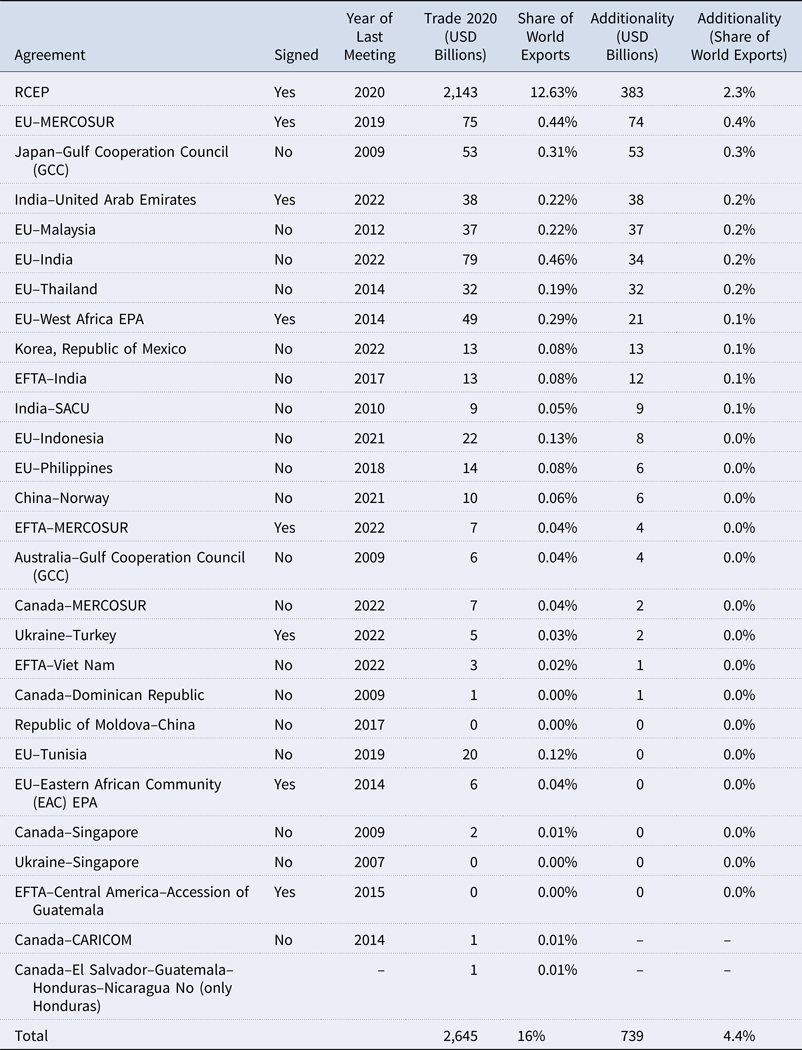

To update the trade coverage analysis after 2010, we used the NSF-Kellogg database, available only to 2016. To compile the list of agreements that came into force after 2016, the primary source is the WTO, whose information ends in 2020. In Table 1, we show only agreements which cover more than 0.1% of world trade, reported to the WTO and signed between 2011 and 2020. We checked our estimates of trade coverage using the DESTA dataset, which provides data on all trade agreements signed since 1945.Footnote 12

Table 1. Larger Agreements signed 2011–2020 and In Force, Reported under Article XXIV

Source: Own Elaboration based on UN COMTRADE, Kellogg Institute, and WTO.

Note: In Commonwealth of Independent States Free Trade Area (CISFTA), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and EU-Southern African Development Community (SADC) it is hard to assess the exact amount of additionality due to previous agreements. We assume 0 to not overestimate additionality. In the case of the UK, we only mention in this table EU–UK, but every agreement signed by the UK in 2020 does not provide additionality. For African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), it should be noticed that not every country (11 out of 54) has deposited its instruments of ratification. Since we take Limão's estimations as the last accurate estimation of trade covered by PTA's, we do not update trade coverage before 2010.

Some trade agreements supersede previous ones among the parties, while other agreements – the mega-regionals – provide an additional layer to previously existing agreements among some parties. To account for the impact on world trade, we include a measure of additional trade covered by each agreement, which we refer to as additionality. For example, the additionality of USMCA is zero, that of Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is partial, and that of EU–Japan is 100%. Of course, this is just a rough metric of impact since new agreements can differ materially from previous ones, deepening them (e.g., CPTPP) or diluting them (e.g., the UK's agreements following Brexit, including the EU–UK).

The RCEP and the EU–UK were signed in 2020 – so they are included in Table 1 – but entered into force in 2021 and 2022 respectively, so they did not provide additionality in 2020.

As Table 1 shows, the exports covered by Agreements reported to the WTO under Article XXIV for 2011–2020 represent 16% of the world total, of which almost 4% was additional. Not shown in Table 1 is the loss of GSP treatment; most notably, China's loss of GSP treatment by the EU reported to the WTO under the enabling clause.Footnote 13

Accounting for the latter, the coverage of PTAs of all kinds has increased by 2 percentage points since 2010, reaching 63.7% of world exports, with reciprocal agreements playing an increasingly important role and unilateral preferences a lesser one.

Ten Agreements explain 93% of the additionality in Table 1. Strikingly, eight of these were among Asian countries or involved an Asian country. EU–Canada and AfCFTA are the only two agreements among the top 8 ranked by additionality that do not include an Asian country as a partner.

In this sense, Asia has been the motor of additionality in trade agreements since the GFC. Two large agreements between Asian countries and the EU (EU–Japan, and EU–Singapore), also came into force. In contrast, the US struck no new agreements other than the renegotiation of NAFTA. The FTA between the US and Korea, which entered into force in 2012, providing additionality of around 0.7% of world exports, was signed in 2007.

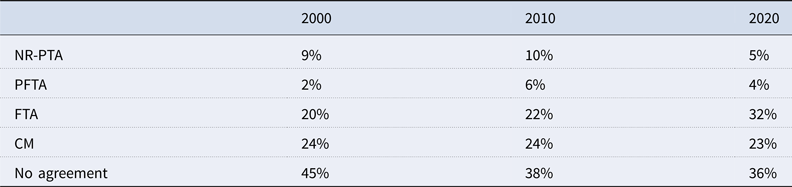

Beyond expanding trade coverage, PTAs since 2010 have been of higher quality since the share of world exports covered by FTAs increased sharply. FTAs cover more trade and entail larger tariff reductions than either NR-PTAs or PFTAs. Whereas unilateral preferences can be subject to many conditions (for example on democracy and human rights) and can be withdrawn, FTAs constitute binding international treaties. As can be seen from Table 2, the share of world exports covered by FTAs increased from 23% in 2010 to 34% in 2020, whereas the share of world exports covered by NR-PTAs and PFTAs fell by nearly the same amount. Taken together, the share of world trade covered by FTAs and CMs increased from 46% in 2010 to 55% in 2020.

Table 2. World's Exports covered by partners with PTA

Source: Own elaboration based on UN COMTRADE and NSF-Kellogg Institute.

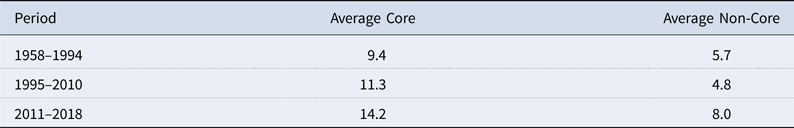

Increased depthFootnote 14 can also be seen by examining the breadth of PTAs, what Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta (Reference Hofmann, Osnago and Ruta2017) call ‘horizontal depth’. They find that, on average, 11 provisions in reciprocal PTAs and CMs were signed between 1990 and 1994 and 23 provisions in those signed between 2010 and 2015. Adopting their method, we draw on a World Bank dataset containing the number of provisions – among 52 options – included in 318 reciprocal PTAs notified at WTO between 1958 and 2019.Footnote 15 In Table 3, we can see that the average number of provisions in recent trade agreements rose in both core and non-coreFootnote 16 groups compared to older agreements.Footnote 17

Table 3. World's Exports covered by partners with PTA

Source: Own elaboration based on UN COMTRADE and NSF-Kellogg Institute.

In addition, Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta (Reference Hofmann, Osnago and Ruta2017), and the database on which they drew,Footnote 18 highlight when provisions were legally enforceable. Nearly all reciprocal PTAs include legally enforceable provisions on tariff liberalization in industrial and agricultural goods. In recent years, however, a much higher share of PTAs contains legally enforceable provisions related to non-tariff measures, such as Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT). For example, all the SPS and TBT provisions in the five agreements notified to the WTO in 2018 and 2019 are legally enforceable, compared to about one-third of the agreements notified in 2000–2001. As a general rule, agreements between developing countries have fewer and less enforceable provisions than those involving an advanced country.

2.4 Outlook

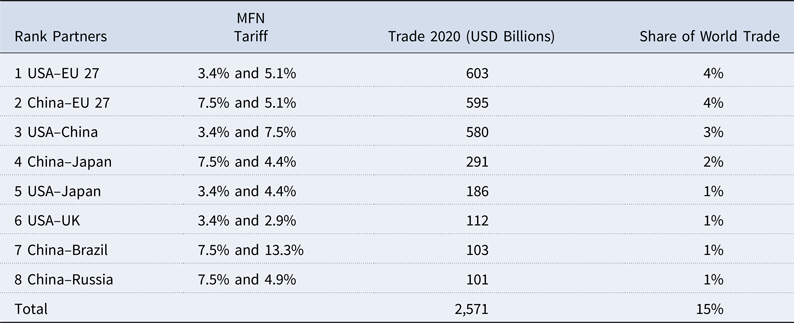

How will the export coverage of PTAs change when agreements, currently under negotiation or that have been concluded and ratified, come into force? Table 4 provides a list of potential future agreements drawing on various sources. Asia continues to be the motor of trade agreements. The largest of these agreements is RCEP, which accounts for nearly 12% of world exports. As of August 2022, RCEP was already in force in China, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and nine other signatories. Only Indonesia, the Philippines, and Myanmar remain to execute the agreement in full. The EU, despite having already achieved the highest PTA coverage, remains very active, with notable potential agreements, which include EU–India and EU–Mercosur.

Table 4. Exports covered by PTAs, including under GSP, in selected groups

Source: Own elaboration based on WTO and research.

Note: New Zealand–Russia, Ukraine–Serbia, EFTA–Russian Federation–Belarus–Kazakhstan, and EU–US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) were not added due to the low probability of success. We have not included UK Agreements since they do not provide additionality. The US started in July/August 2022 negotiations with Kenya and Taiwan, but it is too early to tell whether these negotiations have a good chance of success.

Total exports affected by these potential agreements account for about 16% of the world total in 2020, and their potential additionality, if all were to come into force, would be 4.4% of world exports. We attach a probability of 1 to RCEP coming fully into force, and, quite arbitrarily, a probability of 0.5 to agreements that were concluded but not ratified, and a probability of 0.25 to agreements that are not concluded but were the object of formal meeting in 2021–2022. Using these parameters, we arrive at 468 billion USD of expected additionality. This would imply an increase in the export coverage of 2.8 percentage points, which would bring the total coverage of PTAs to 66.5% of world trade.

3. Systemic Considerations

The trade coverage of PTAs is now so extensive that under any assumption about the future of multilateral trade rules, they will play a major role in keeping large parts of world trade secure. In many instances, PTAs now include more parties and have coverage that is both broader (e.g., market access in services, investment) and deeper, i.e., ‘behind the border’ than under the WTO and are increasingly more enforceable. Recent research has shown that ‘deep PTAs’ can benefit third parties, reducing concerns about trade diversion due to tariffs and complex rules of origin.

However, there are no trade deals among the regional hegemons, and the parts of world trade that are most secure are – with some exceptions – predominantly those that are intra-regional. This situation is not entirely new, of course, dating back to the precursors of the EU's single market, the establishment of ASEAN in the late 1960s, and the coming into force of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1995. However, compared to, say, a decade ago, WTO rules are less secure, and mega-regional agreements in Asia have consolidated.

In this section, we try to discern the systemic implications of these developments against the background of a deepening rift between China and the US and its allies. We argue that based on current trends, interregional trade will become intrinsically more uncertain and unstable than that within the world's main producing regions, causing a partial fragmentation of world trade. Contrary to the views of many politicians and commentators who are comfortable with this course, regional markets will go only so far. In 2021, 70% of North America's exports, 41% of Asia's, and 31% of Europe's were destined outside the region, while Africa and Latin America depend on other regions for 85% of their exports.Footnote 19 Trade links today are global, as they have been as far back as the great explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries, only they run deeper. The globalization of production entails trade in machines, components, and raw materials that are far larger than those in consumer goods. Regionalization is bound to lead to disruption, duplication, and, ultimately, lost efficiency.

3.1 The Mega-Regional Trend

Before December 2018, when the CPTPP came into force, there had been no new mega regional agreement since NAFTA a generation prior. In the years since, three other major agreements were concluded: the RCEP among 15 countries in Asia, the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), and the AfCFTA. USMCA is already fully in force. The other agreements are in force in several of their members, and we consider that all will be fully in force in the coming years. The members of these four mega-regional agreements together account for over 60% of the world GDP. If we add the oldest mega-regional agreement to the list, the European Union (EU) after Brexit, countries accounting for over 78% of world GDP are now members of mega-regional agreements.

RCEP, which includes 20 chapters, is notable because it includes China and accounts for about 12% of world trade and 30% of the world GDP. However, since its 15 members, all in Asia were already linked by various PTAs, RCEP's trade coverage additionality is far less, about 2.1%. Most importantly, RCEP connects three manufacturing giants, Footnote 20 China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea for the first time with lower tariffs on about 90% of products and simplified rules of origin, facilitating the progress of regional value chains. The participation of these three nations places RCEP, an agreement that is structured to evolve and deepen (a ‘living agreement’, in the mode of its predecessor, ASEAN), at the center of the world's largest manufacturing hub by far – even without counting access to the resources and markets of other parties to the agreement.

Beyond its economic impact, RCEP has profound political implications. Even though China was not the prime mover of RCEP (ASEAN initiated the agreement), it demonstrates China's commitment to trade liberalization and regional cooperation (Shimizu, Reference Shimizu2022; Drysdale and Armstrong, Reference Drysdale and Armstrong2021; Petri and Plumer, Reference Petri and Plummer2020). India's late decision to drop out of the agreement diminishes its scope but further underscores China's rising political influence and the centrality of its economy in Asia.

CPTPP, the successor to the ill-fated TPP, covers 30 chapters, including innovative provi sions on subsidies and state-owned enterprises. However, unlike the other mega regionals, CPTPP is not confined to one region unless one considers the Pacific as one. Japan, the world's fourth-largest economy, and the other ten members span three continents, Asia, South America, and North America. Because of its geographic scope, diversity, depth, and provisions for the accession of new members to all the PTAs in force, CPTPP is perhaps the most likely to serve as a partial countertrend to the regionalization of world trade. It may also become a testing ground for new disciplines that can become multilateral or that can be copied into other PTAs. In this regard, the agreement's systemic importance as a ‘multilateral mega-regional’ will be enhanced if either the United Kingdom's or China's application to join succeeds.

The USMCA contains 34 chapters and 12 side letters (Villarreal and Fergusson, Reference Villarreal and Fergusson2020), adding to NAFTA innovative features on electronic commerce, intellectual property protection, state-owned enterprises, and more enforceable labor and environmental standards. However, USMCA provides no significant additional trade liberalization, has more restrictive rules of origin in automobiles than NAFTA, and includes a 16-year sunset clause which introduces uncertainty in investment decisions. The main consequence of USMCA from a systemic perspective is that it precludes the discontinuation of NAFTA, keeping the US tightly connected to its two largest trading partners.

AfCFTA covers all countries in Africa and is the smallest of the new mega regionals terms of trade coverage. Its systemic significance lies in recognizing the importance of trade by the world's poorest nations. Nearly all its members were until recently colonized and have been skeptical of trade liberalization, yet AfCFTA was negotiated autonomously without the significant involvement of Europeans. African nations still trade overwhelmingly outside their region. Still, when interregional trade becomes less secure, it can be seen as a vehicle to boost intraregional trade and as a form of partial insurance. The AfCFTA also holds the promise of improved coordination of positions across the continent in bilateral and multilateral negotiations.

3.1.1 Divergent Paths

The trade coverage of PTAs varies greatly since nations have followed vastly different paths in negotiating them, especially in recent years. Under President Trump, the US withdrew from the TPP, and the last trade agreement signed by the United States that added coverage to its exports was with the Republic of Korea, signed in June 2007 and entered into force in March 2012, and Colombia, signed in November 2006 and entered into force in May 2012. Including USMCA, about 44% of US exports are now under trade agreements. This contrasts with the members of the EU-27, whose exports are 81% covered by PTAs, of which the EU single market covers 61%. Notable new EU agreements negotiated with third parties since 2010 include those with Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom, whose exit from the EU represents a step backward in terms of depth. While the EU presently has active negotiations with five partners,Footnote 21 and has concluded but not signed or ratified negotiations with another 23 partners,Footnote 22 the Biden Administration has put all bilateral trade negotiations on indefinite hold and declined to pursue renewal of Trade Promotion Authority which expired in July 2021.

As we can see in Table 5, China was a major beneficiary of GSP but has progressively graduated, so the share of China's exports covered by PTAs has declined, with a sharp fall in 2015 from 68% – GSP accounted for 35% of the total – to 49%, with only 9% accounted for by GSP because the EU withdrew its preferences. However, in recent years, China has been among the most active in negotiating reciprocal trade agreements, many related to its Belt and Road initiative. China's notable FTAs since 2010 include those with Costa Rica in 2010, EFTA in 2013, Switzerland in 2014, Korea and Australia in 2015, Georgia in 2017, and the RCEP. With the coming into force of the RCEP, China's total PTAs export coverage will increase from 49% to 55%. China concluded a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with the EU, now on hold, and has applied to join the CPTPP. Both these initiatives signal that China is willing to engage in agreements that entail deep reforms on subsidies and state-owned enterprises, among others.

Table 5. Exports covered by all PTAs (Exports covered by NR-PTA or GSP)

Source: own elaboration based on UN COMTRADE and NSF-Kellogg Institute.

Note: EU-27 Refers to the average of individual EU members and includes intra-EU trade. The total number reflects the share of exports covered by every type of PTA, while the number in parenthesis states how much trade is covered by GSP or NR-PTA.

India has been a passive player in trade agreements, withdrawing from RCEP at the last minute. It relies on the GSP for more than 38% of its exportsFootnote 23 and has negotiated some low-quality trade agreements with other developing countries. Only 19% of its trade is covered by FTAs. The last significant FTA concluded by India with Japan dates back to February 2011.

Perhaps surprisingly for a country with a strong export orientation, Japan had until recently a low share of trade covered by PTAs. Japan's top five export markets are the US, China, Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, Province of China. RCEP will change the picture since it includes Korea, China, and New Zealand,Footnote 24 countries with which Japan does not have trade agreements. Once RCEP comes fully into force in all its signatories the share of Japan's exports covered by PTAs will than double, from 31% to 63%.

Brazil saw the export coverage by PTAs decline from 84% to 33% in 2020. This is accounted for by Brazil's loss of GSP in the EU in 2014 and Brazil's soaring commodity exports to countries with which it does not have PTAs, mainly in Asia. China alone now accounts for 33% of Brazil's exports.

3.1.2 A Rules Vacuum?

The number of bilateral relationships covered by some type of PTA has increased in the last 20 years. Out of 37,830 bilateral combinations between the 195 countries (195 × 194),Footnote 25 in 2000, 16.5% had some type of PTA. That number increased to 26.8% in 2010 and 28.4% in 2020. Considering bilateral trade relationships not covered by PTAs, only eight account for 1% of world trade or more, as shown in Table 6. Only one of these important relationships, China–Japan, will be covered by an already concluded agreement (RCEP).

Table 6. Exports covered by PTAs, including under GSP, in selected groups

Source: Own Elaboration based on NSF Kellogg Institute and UN COMTRADE.

Note: Average MFN (simple, 2020) based on WTO, World Bank, and WITS.

The disabling of the WTO's Appellate Body and the threat posed to the system by rule breaking means that these big trading relationships risk becoming ungoverned by any rule. This is why three of the largest traders, Brazil, China, and the European Union, established the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration (MPIA), an agreement to resort to arbitration under WTO Article 25 in the event of a dispute. However, the MPIA includes only 28 WTO members and is still to be fully tested,Footnote 26 and does not include the United States, Japan, India, and the United Kingdom among the large traders.

Summarizing, all major traders are likely to lose by varying degrees from the fragmentation and regionalization trend. Members of the EU may be less adversely affected than China and the US on account of the large share of their trade that is intra-EU and covered by PTAs with non-members and because of the rivalry between the two super powers. China's geographic position in Asia, the world's largest and fastest-growing region, and its membership in RCEP will provide it with some advantages relative to the EU and the US, especially if the latter stands back from new trade agreements. Finally, although the China–EU–US triangle comprises only 11% of world trade in goods, that arena will most likely determine whether the fragmentation and regionalization of world trade will prevail.

4. Policy Observations, and Conclusion

PTAs are a source of the resilience of the trading system, and the pursuit of high-quality (deep, broad, enforceable) PTAs with major trading partners will help navigate an increasingly uncertain trade policy environment. However, the world's largest trade relationships, along with many smaller ones, may fall into a rules vacuum, governed neither by enforceable WTO rules nor by PTAs.Footnote 27

4.1 Worst Case Scenario

Under a worst-case scenario, the largest players will aim to protect and subsidize production at home and concentrate their trade and foreign investment in their wider sphere of influence, a trend that is already becoming apparent. This push for ‘reshoring’, ‘near-shoring’, and ‘friend-shoring’ will increase costs and trigger responses along similar lines or outright retaliation. It may also have the opposite consequence to that intended, which is to encourage international firms to relocate closer to markets, for example, to produce in China for China.

Fearing the absence of multilateral rules, smaller nations seek to establish agreements with the regional hegemons or reinforce existing ones. To mitigate the risk of one-sided deals, smaller countries may try to trade off the hegemons. Ultimately, depending on power, they may be forced to choose one side, and divergent trade interests among countries in the same region may push members in different directions. Even when trade interests coincide, security interests may not, adding to the risk of politicization and weaponization of trade and increasing trade policy uncertainty.

As stressed by those who early on saw PTAs as ‘stumbling blocks’ of multilateralism, the dynamics inherent in the proliferation of PTAs are worrisome. It is notable that already some small and middle-sized countries, such as Chile, Mexico, and Morocco, are party to numerous PTAs covering 85% or more of their trade. In a sense, these nations have already hedged their geopolitical bets, which is a good thing. But is there still sufficient incentive for countries so reliant on PTAs to engage in WTO negotiationsFootnote 28, and is there a systemic tipping point beyond which reliance on PTAs makes multilateral deals, which require consensus, impossible?

This worst-case fragmentation scenario is reminiscent of the trade relations of the 19th and 18th centuries when empires and colonial systems competed for markets and natural resources and imposed trade rules and navigation laws in their sphere of influence – frequently contested and resulting in military conflict. The old idea that trade helps promote peace is often dismissed as simplistic, as one can cite counter examples, but it is notable that while wars among the great powers occurred almost continuously over the last six centuries, there have been no wars directly involving the great powers since the Korean War, 1950–1953.Footnote 29

4.2 The Permanence of WTO Centrality

It is difficult to see how the fragmentation and regionalization of world trade can be avoided without a return to enforceable multilateral rules that are observed by everyone, beginning with the trading powers. This will require reinstatement of the WTO Appellate Body, or a reformed version that addresses the concerns expressed by the United States, or – as a second-bestFootnote 30 – compulsory arbitration under the aegis of the WTO as envisaged by the MPIA and applied to all members. At MC-12, held in Geneva in June 2021, Ministers took a notable step, agreeing to talks aimed at securing a fully functioning dispute settlement system by the next Ministerial in 2024.

At the same time, to remain relevant, the WTO must advance on multilateral disciplines, dealing with the issues members confront in a changing global economy. As many have argued, there are important cases where this is no longer possible if all 164 members have to agree (or there must be no strong dissenting voice) under the consensus procedure. The WTO membership is too diverse, and the issues are too complex. Moreover, the increased importance of PTAs has probably reduced the incentive and urgency to strike deals in some instances. Forward movement in these circumstances will require plurilateral deals, agreements on market access in a specific sector or on a specific theme that a critical mass of members can strike and whose benefits may or may not accrue to the rest of the membership. In 2021, 67 WTO members reached an open plurilateral agreement (OPA), one where benefits accrue to all members, irrespective of their participation in domestic services regulation. Other OPAs are advancing, such as investment facilitation. The last closed plurilateral agreement, whose benefits accrue only to signatories, was on government procurement, which has undergone several revisions and required a waiver from the membership under the Uruguay Round. Meanwhile, deals among the whole membership were reached at MC-12 in June 2022 on fisheries and pandemic response. These agreements were of limited importance, but they showed that advancing trade disciplines in a multilateral context is still possible.

4.3 Deals among the Hegemons

Encouraging as these recent developments are, the thorniest issues dividing the hegemons (or those dividing China on one side and the EU and the US on the other) are unlikely to be resolved in a WTO context, at least not in the first instance. We refer here to rules on subsidies, state-owned enterprises, forced technology transfer and joint ventures, intellectual property protection, investment and export restrictions, and climate-related trade measures, among others. These issues are complex, entail policies that are often specific to the hegemons, and have become entangled with national security concerns. Realistically, progress on them is unlikely to be achieved in a multilateral forum but will instead require direct negotiations between the hegemons.

Negotiations among the hegemons are least likely to succeed amid acute geopolitical tensions, as we have today. But, in a more propitious context and with determined leadership, future deals are not to be excluded. Despite some highly visible recent disputes, such as those over aluminum and steel and subsidies on electric vehicles, trade and investment relations between the EU and the US are extensive and remain quite free. Many attempts have been made to strike a deal covering EU–US trade to remove remaining barriers at the border and, especially behind it. The latest effort, the TTIP, was abandoned in 2019 when it became evident that neither side was willing to make significant concessions. But the war in Ukraine has injected new life into the transatlantic alliance, and there is a keen sense that trade relations between the EU and the US should be better regulated somehow. A revival of TTIP is not on the horizon, but some unpacking of it is possible, as is being attempted in the EU–US Trade and Technology Council, for example. Such steps are needed, not only to deal with many outstanding regulatory issues but also to guard against backtracking.

The EU is torn between its geopolitical alliance and security dependence on the US and the big trade and investment opportunities available in a rising China. Negotiations between China and the EU have advanced further than many recognize with the conclusion of the China–EU Comprehensive Agreement of Investment (CAI), which had been intended as a first step toward negotiating a China–EU FTA. The CAI has been shelved in the ratification process over a dispute on human rights. Beyond opening up several service sectors to investors, the CAI made significant progress in establishing disciplines on subsidies, forced joint ventures, and forced technology transfer (Dadush and Sapir, Reference Dadush and Sapir2021). It is difficult to see any further advance on these issues as war rages in Ukraine, and China's position on Russia's invasion of Ukraine is ambiguous. However, in an improved geopolitical context, progress is evidently possible, as shown by the groundwork that has already been laid.

As their rivalry intensifies, the China–US trade relationship is the most problematic. The phase-1 deal struck under President Trump consisted essentially of a Chinese promise to buy more American goods, in blatant violation of WTO rules, and the targets remain unmet. Phase 2 negotiations were intended to deal with structural reforms but were shelved under President Biden. Indeed, relations with China have deteriorated further under the present administration. Not only is the geopolitical context decidedly unpropitious for an accommodation with China, but little has been done so far to lay the groundwork for a potential deal.

One should not despair, however. Even as the Soviet Union and the US saw each other as existential threats, they found common ground in nuclear disarmament, and there were extended periods when tensions were allayed. As during the Cold War, there are guardrails around the China–US relationship because open warfare between nuclear powers is unthinkable. Moreover, the opportunity to cooperate is far greater because of the extensive trade and investment links and the common threats of climate change, pandemics, and financial instability.

The best-case scenario for the trading system almost certainly begins with an accommodation between China and the United States. In the concluded CAI negotiations and its application to CPTPP and other ways, China is signaling that it is willing to consider trade reforms that address some of the partners’ concerns, even though there is no sign that the Chinese leadership is about to change its statist model and tight control. The US says it sees the relationship with China as one of competition, not enmity. If that is true, sooner or later, the US leadership will recognize that it will not prevail in that competition by eschewing trade agreements, refusing WTO rules, or decoupling from China, a course that even its closest allies reject.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5PL1KC (Dominguez Prost, Reference Dominguez Prost2023).