No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

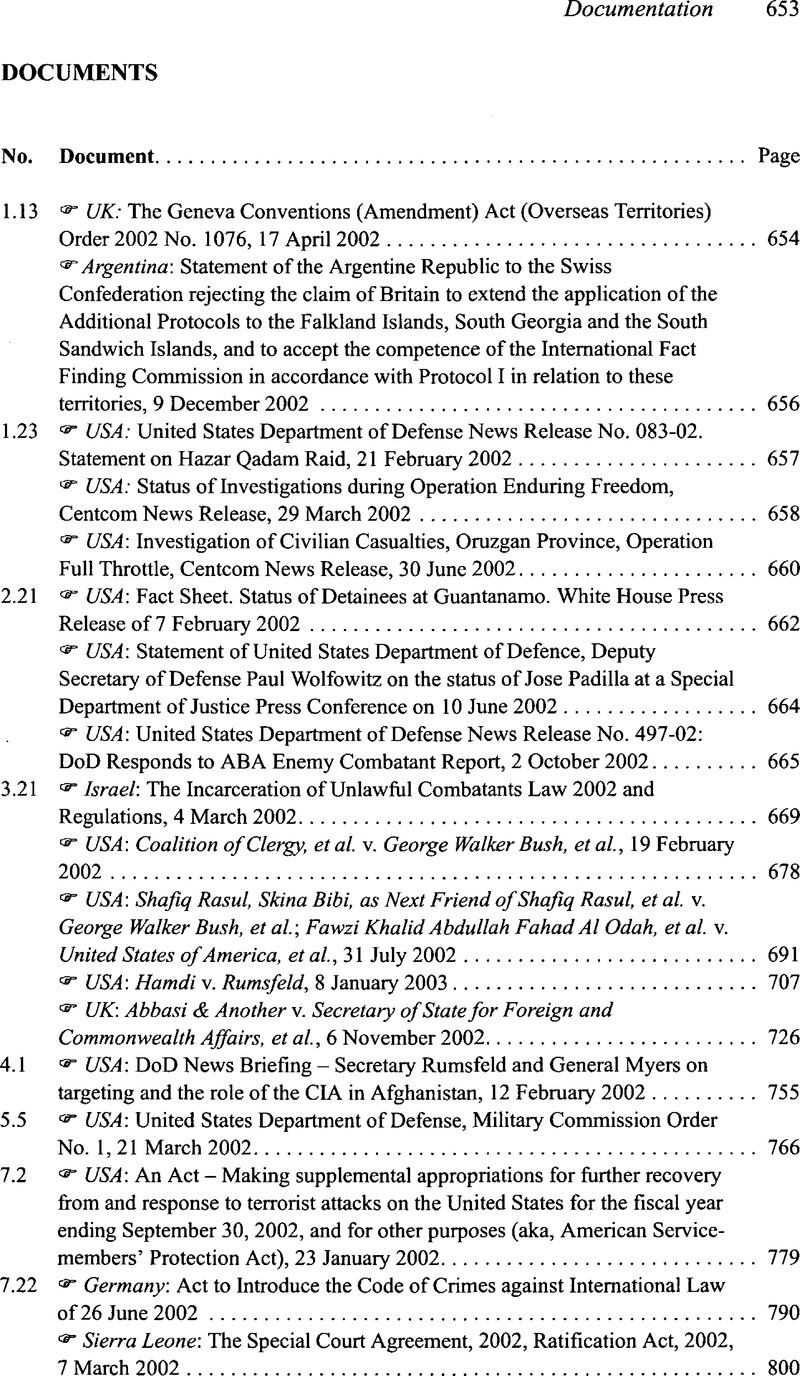

Documents

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Documentation

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © T.M.C. Asser Instituut and the Authors 2002

References

2. [1] 5 & 6 Eliz. 2.c.52.

3. [2] 1995 c.27.

4. S.I. 1959/1301.

5. [4] See S.I. 1998/1754.

6. [1] AAA = Anti-Aircraft Artillery [editor's note].

7. [2] The AC-130 is a medium-sized cargo plane, commonly known as a “Hercules,” converted to combat use by placing several machine guns and/or rapid-firing cannon to fire out of windows on one side of the aircraft. The AC-130 attacks a target on the ground by circling the target with its “armed” pointed towards the target. [editor's note]

8. Footnotes omitted. Translation provided with the courtesy of the Legal Department, International Committee of the Red Cross, Tel Aviv.

9. [1] On February 11, 2002, after the parties had filed their respective briefs on the threshold jurisdictional issues, petitioners filed a “First Amended” petition purporting to add a claim under what they refer to as the “cruel and unusual clause” of the Eighth Amendment. Counsel for petitioners had acknowledged at the hearing “I'm going to have to proceed on the petition as it is right now. And if a decision is reached to add an Eighth Amendment claim, then I'm going to have to ask for permission to do that.” He neither sought nor received permission. Moreover, the court instructed the parties that “if there is jurisdiction the petition could be amended at a later time.” (Tr., p.10-11) The Amended Petition does not affect, much less cure, the jurisdictional defects described below, and this Order applies to both petitions.

10. [2] The foregoing discussion involves only the writ of habeas corpus “ad subjiciendum,” which compels an inquiry into the cause of restraint. There are other writs of habeas corpus, but they are irrelevant here.

11. [3] Compare Groseclose v. Dutton, 594 F. Supp. 949 (M.D. Tenn. 1984), where next friends, including a death row inmate, minister and two anti-death penalty organizations, were permitted to proceed. There, the real party in interest did not oppose their efforts and the petitioners demonstrated that his previous waiver of the right to file a habeas petition was involuntary. Groseclose, 594 F. Supp. at 951, 961-62.

12. [4] The Court may take judicial notice of the information in the articles attached to the petition. Fed. R. Evid. 201(b). Indeed, both sides cite these articles for different purposes.

13. [5] In using the term “uninvited meddlers” in Whitmore, Chief Justice Rehnquist cited to United States ex rel. Bryant v. Houston, 273 F. 915, 916 (2d Cir. 1921). There, the named petitioner failed to disclose anywhere in her petition who she was, what relationship, if any, she had with the real party in interest or whether the real party was unable to file the petition himself. Chief Justice Rehnquist also cited to Rosenberg v. United States, 346 U.S. 273, 291-292, 75 S. Ct. 1152, 1161-1162 (1953). There, the real parties in interest already had several attorneys but their habeas petition was prepared by another lawyer who sought to intervene. Justice Frankfurter noted that the legitimate counsel of record “simply had been elbowed out of the control of their case” by the lawyer who filed the habeas petition. Idem.

14. [6] As Justice Frankfurter stated in a different context, “Nor does law lag behind common sense.” Ludecke v. Watkins, 335 U.S. 160, 167, 68 S. Ct. 1429, 1432 (1948).

15. [7] The court is not suggesting that the mere failure of a “next friend” to establish direct communication with the prisoner and obtain explicit authorization from him is enough to preclude “next friend” petitioners. If it were, then there would be an incentive for the government to keep all captives, even United States citizens, incommunicado. Although respondents are not advocating that unacceptable and illegal result, a too-expansive interpretation of “uninvited meddlers” could lead to it.

16. [8] At the hearing today, Prof. Erwin Chemerinsky, one of the named petitioners (but not the author of petitioners’ court papers), argued that the requirement that “next friends” demonstrate a “significant relationship” with the real parties in interest should be relaxed where the real parties lack access to court. He urged that general principles of standing under the constitutional requirements of Art. III favor such an approach. The court chooses to apply the standards enunciated in the Whitmore-Massie line of cases and notes that in Whitmore the Supreme Court noted that the limitations on standing that it was applying were in fact consonant with Article III, and were not based merely on “prudential” limitations. 492 U.S. at 156 n. 1.

17. [9] In Braden v. 30th Judicial Circuit Court, 410 U.S. 484, 93 S. Ct. 1123 (1973), the Supreme Court noted that a writ of habeas corpus is issued to the person who has allegedly detained the prisoner unlawfully and held that a federal court with jurisdiction over the custodian can exercise jurisdiction even if the prisoner is outside that court's jurisdiction.

18. [10] Despite the clear holding of these cases, petitioners' counsel argued in his brief that section 1391 permits this court to subject the respondents to jurisdiction on this basis.

19. [11] The Supreme Court has “characterized as ‘well-established’ the power of the military to exercise jurisdiction over … enemy belligerents, prisoners of war or others charged with violating the laws of war.” Johnson, 339 U.S. at 286 (citations deleted).

20. [12] In emphasizing the importance of sovereignty, the Court distinguished its earlier decision in In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. I, 66 S. Ct. 340 (1946). There, a Japanese general convicted by an American Military Commission in the Philippines, challenged the authority of the Commission to try him. The Supreme Court denied his habeas petition on the merits. The Johnson court noted that, unlike the status of Guantanamo (see infra), the United States had “sovereignty” over the Philippines at the time, which is why Yamashita was entitled to access to the courts. Id. at 781.

21. [13] It appears that the Guantanamo detainees will also be subjected to trial before military commission. On November 13, 2001, the President issued an Executive Order entitling members of Al Qaeda and other individuals associated with international terrorism who are under the control of the Secretary of Defense to be tried before “one or more military commissions” that will be governed by “rules for the conduct of the proceedings …[and] which shall at a minimum provide for … a full and fair trial, with the military commission sitting as the triers of both fact and law …” See Detention, Treatment and Trial of Certain Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism, 66 Fed. Register 57,833 (November 13, 2001). Thus, it appears that the detainees are similar to the petitioners in Johnson in this respect, too.

22. [14]. The cases on which petitioners mainly rely to avoid this result do not support their arguments. United States v. Corey, 232 F.3d 1166 (9th Cir. 2000), not a habeas case, merely reached the unexceptional conclusion that federal courts have jurisdiction over a criminal case charging a United States citizen with offenses committed at United States installations abroad. Cobb v. United States, 191 F.2d 604 (9th Cir. 1951) does not hold - indeed, rejected the view — that America's exclusive control over the Guantanamo Naval Base constitutes de jure sovereignty; Okinawa, not Guantanamo Bay, was at issue in Cobb and the court found that de jure sovereignty over Okinawa had not passed to the United States, so Okinawa was still a “foreign country” within the meaning of the Federal Tort Claims Act. Idem at 608. Finally, the judgment in Haitian Centers Council, Inc. v. McNary, 969 F.2d 1326 (2d Cir. 1992) was vacated by the Supreme Court in sale v. Haitian Centers Council, Inc., 509 U.S. 918, 113 S. Ct. 3028 (1993).

23. [15] The President recently declared that the United States will apply the rules of the Geneva Convention to at least some of the detainees. See “U.S. Will Apply Geneva Rules to Taliban Fighters,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 2002 at Al.

24. [I] The Court notes that, at least for Petitioner David Hicks in the Rasul case, diplomatic efforts by the Australian government have already commenced. First Am. Pet. for Writ of Habeas Corpus (“Am. Pet”), Ex. C., “Affidavit of Stephen James Kenny,” Attach. 2 (Letter from Robert Cornall, Australian Attorney-General's Office to Stephen Kenny, counsel for Petitioner Terry Hicks) (“Australia has indicated to the United States that it is appropriate that Mr Hicks remain in US military custody with other detainees while Australia works through complex legal issues and conducts further investigations … Australian authorities have been granted access to Mr Hicks and will be granted further access if required.”).

25. [2] In reaching its decision in the Rasul case, the Court considered the First Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, the Exhibits to the Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, the Memorandum in Support of the Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Respondents' Motion to Dismiss Petitioners' First Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Petitioners' Memorandum in Opposition to Respondents' Motion to Dismiss, and Respondents' Reply in Support of Their Motion to Dismiss Petitioners' First Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus. In reaching its decision in the Odah case, the Court considered the Amended Complaint, Plaintiffs' Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, Plaintiffs' Request for Expeditious Hearing on Plaintiffs' Motion for a Preliminary Injunction and Supporting Statement of the Facts that Make Expedition Essential, Defendants' Motion to Dismiss Plaintiffs' Complaint and Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Motion to Dismiss Plaintiffs' Complaint and Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, Defendants' Reply in Support of Motion to. Dismiss, Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Leave to Late File Their Reply In Support of Defendants' Motion to Dismiss and Response to Plaintiffs' Request for Expeditious Hearing, Plaintiffs' Consent Motion for Leave to File Post-Argument Brief Correcting Erroneous Statements by Defense Counsel at Oral Argument, Defendants' Response to Plaintiffs' Post-Argument Brief, and Plaintiffs' Reply to Defendants' Response to Plaintiffs' Post-Argument Brief.

26. [3] After full briefing and oral argument on Defendants' Motion to Dismiss in the Odah case, Plaintiffs filed an Amended Complaint, which they filed as of right pursuant to Rule 15 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. In a conference call with the Court, Plaintiffs represented that there were three specific differences between the Amended Complaint and the original Complaint. First, the Amended Complaint added two new plaintiffs to the action, a Kuwaiti national held at the military base at Guantanamo Bay and a member of his family who brings the suit on his behalf. Originally, there had only been twenty-two Plaintiffs. Compare Compl. 3, 4, with Am. Compl. 3, 4. Second, Plaintiffs abandoned their request that the Court order Defendants to turn Plaintiffs, held at the military base at Guantanamo Bay, over to the Kuwaiti government. Compl. 44. Third, Plaintiffs made an effort to clarify the four specific requests for relief that they seek in this case. Compare Compl. /42, with Am. Compl. 40. Ordinarily, when the Court receives an amended complaint after a defendant files a motion to dismiss, it denies the motion to dismiss without prejudice and requests that the defendant re-file the motion based on the allegations presented in the amended complaint. In this case, based on the Court's review of the Amended Complaint, it appears that such a procedure would be a useless exercise since the legal theories underlying Defendants' present motion o dismiss will not be affected by the filing of the Amended Complaint. Defendants agree with the Court and contend that the amendments will not impact upon the Court's ruling on the motion to dismiss. Accordingly, the Court will apply Defendants' motion to dismiss to Plaintiffs' Amended Complaint. See Nix v. Hoke, 62 F. Supp. 2d 110, 115 (D.D.C. 1999) (citing cases); see also 6 Wright, Charles Alan & Miller, Arthur R., Federal Practice and Procedure § 1476 (2d ed. 1990)Google Scholar (“[D]efendants should not be required to file a new motion to dismiss simply because an amended pleading was introduced while their motion was pending. If some of the defects raised in the original motion remain in the new pleading, the court simply may consider the motion as being addressed to the amended pleading. To hold otherwise would be to exalt form over substance.”).

27. [4] The Court's initial briefing schedule in the Odah case did not contemplate that Defendants would be moving to dismiss the entire action. Rather the Court's briefing schedule set forth a date for Defendants to respond to Plaintiffs' motion for preliminary injunction. Odah v. United States, Civ. No. 02-828 (D.D.C. May 14, 2002) (order setting forth briefing schedule). Instead of filing an opposition to the motion for a preliminary injunction, on the date that their opposition to the preliminary injunction was. due, Defendants moved to dismiss the entire case (and, by inference, the motion for preliminary injunction). Plaintiffs filed a timely opposition to Defendant's motion. Defendants then filed a reply, which Plaintiffs argued was inappropriate since the Court's initial briefing schedule did not set a date for Defendants to file a reply. However, when the Court set the initial briefing schedule, it was only concerned with receiving a response to the motion for preliminary injunction. Defendants were clearly within their right to move for dismissal of the entire action, which would permit them the opportunity to file a reply to their motion to dismiss. Although Defendants filed their reply late, the Court shall grant them leave to file the reply. To the extent that Plaintiffs' opposition to Defendants' filing of a reply brief esponds to new issues first raised in Defendants' reply, the Court shall consider Plaintiffs' response as a surreply to Defendants' motion to dismiss.

28. [5] For purposes of the instant motions to dismiss, the allegations of the Amended Petition/ Amended Complaint are taken as true. The facts in this section are presented accordingly, and do not constitute factual findings by this Court.

29. [6] While denying a role in any terrorist activity, Petitioners in their Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus conspicuously neglect to deny that they took up arms for the Taliban. In fact, in an exhibit attached to the Amended Petition, Petitioner Terry Hicks, who has brought this suit on behalf of his son, indicates that his son had joined the Taliban forces. Am. Pet., Ex. C., “Affidavit of Stephen James Kenny,” Attach. 8 (Letter from Stephen Kenny, counsel for Petitioner Terry Hicks to Respondent Bush) (“It is our client's understanding that his son subsequently joined the Taliban forces and on 8 December 2001 was captured by members of the Northern Alliance.”). Interestingly, this fact has been omitted from the text of the Amended Petition, but can be found only by a careful reading of an exhibit attached to the Amended Petition. Id.

30. [7] It has not been confirmed that Plaintiff Mohammed Funaitel Al Dihani is currently in custody at Guantanamo Bay. Am. Compl.¶ 21.

31. [8] Notably, there are a few attachments to the Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus which the Court cites in this Memorandum Opinion. The Court does not consider these matters to be outside the pleadings because they were attached as exhibits to the Amended Petition.

32. [9] Plaintiffs cite to the habeas statutes as a basis for the Court's jurisdiction over their claims. Am. Compl. 1. Even though Plaintiffs have disavowed that their action is one sounding in habeas, the Amended Complaint continues to rely on the habeas statutes to provide this Court with jurisdiction.

33. [10] Plaintiffs' citation to Brown v. Plaut is similarly unavailing. Pls.’ Opp'n at 20 (citing Brown v. Plaut, 131 F.3d 163 (D.C. Cir. 1997)). The Brown case involved a prisoner's challenge to a decision to place him in administrative segregation. The Court of Appeals held that such action did not have to be brought as a petition for writ of habeas corpus. Id. at 167. In that case, the appellate panel observed that the Supreme Court “has never deviated from Preiser's clear line between challenges to the fact or length of custody and challenges to the conditions of confinement.” Id. at 168. Plaintiffs' broad request to be produced before a tribunal is obviously a challenge “to the fact … of custody.” Id. Accordingly, Brown does not apply to this case.

34. [11] Alternatively, the Court notes that in order for the government to be sued under the Alien Tort Statute, the government must waive its sovereign immunity. FDIC v. Meyer, 510 U.S. 471, 475 (1994) (“Absent a waiver, sovereign immunity shields the Federal Government and its agencies from suit.”). Plaintiffs argue that Section 702 of the Administrative Procedure Act provides such a waiver. Pls.' Opp'n at 24 (citing Sanchez-Espinoza v. Reagan, 770 F.2d 202, 207 (D.C. Cir. 1985) (Scalia, J.) (stating that while the Alien Tort Statute does not provide a waiver of sovereign immunity, “[w]ith respect to claims against federal [officials] for nonmonetary relief … the waiver of the Administrative Procedure Act … is arguably available”) (emphasis in original)). Assuming that Section 702 of the Administrative Procedure Act provides a waiver, the Court finds that the actions of the government in this case would be exempt by 5 U.S.C. § 701(b)(1)(G) (providing an exemption for, “military authority exercised in the field in time of war or in occupied territory”). Cases that have analyzed Section 701(b)(1)(G) have had occasion to address it only in the context of “judicial interference with the relationship between soldiers and their military superiors.” Doe v. Sullivan, 938 F.2d 1370, 1380 (D. C. Cir. 1991). Despite the absence of pertinent case law, the language of Section 701(b)(1)(G) supports the view that this Court is unable to review the claim Plaintiffs make under the Administrative Procedure Act. There is no dispute that Plaintiffs were captured in areas where the United States was (and is) engaged in military hostilities pursuant to the Joint Resolution of Congress. Am. Compl. 16 (“the Kuwaiti Detainees were seized against their will in Afghanistan or Pakistan”). This situation plainly falls within Section 701(b)(1)(G). The Court was unable to find any material in the legislative history that addressed Section 701(b)(1)(G) of the Administrative Procedure Act, see, e.g., S. Rep. No. 89-1350, at 32-33 (1966); H.R. Rep. No. 89-901, at 16 (1965), and the parties have not provided any legislative history, that would change the Court's view of this provision. Furthermore, granting Plaintiffs relief under the Administrative Procedure Act would produce a bizarre anomaly: United States soldiers would be unable to use the courts of the United States to sue about events arising on the battlefield, while aliens, with no connection to the United States, could sue their United States military captors while hostilities continued. Such an outcome defies common sense. Accordingly, even if the Court did not treat the Odah case as a petition for writs of habeas ccorpus, Count III, brought pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act, fails because the actions complained of by Plaintiffs are exempt pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 701(b)(1)(G). Additionally, as Plaintiffs have not set forth another basis for the government's waiver of its sovereign immunity outside the Administrative Procedure Act, Count II brought pursuant to the Alien Tort tatute would be subject to dismissal.

35. [12] The government has encouraged this Court to take “judicial notice” that these individuals are “enemy combatants.” Tr. 9-10. In reviewing this case, the Court has taken the allegations in the Amended Petition and Amended Complaint as true as required by Rule 12(b)(1). Petitioners and Plaintiffs allege that the individuals held at Guantanamo Bay were initially taken into custody and detained in Afghanistan and Pakistan where military hostilities were in progress. Am. Pet. 22-24; Am. Compl. 16. David Hicks, who had joined the Taliban, see supra note 6, arguably may be appropriately considered an “enemy combatant.” The paucity, ambiguity, and contradictory information provided by the Amended Petition and the Amended Complaint about Petitioners Rasul and Iqbal and the twelve Kuwaiti Plaintiffs held at the military base at Guantanamo Bay prevents the Court from likewise concluding that these individuals were engaged in hostilities against the United States, or were instead participating in the benign activities suggested in the pleadings. While another court with apparently the same factual record has labeled, without explanation, the individuals held at Guantanamo Bay “enemy combatants,” Coalition of Clergy v. Bush, 189 F. Supp. 2d, 1036, 1048 (C.D. Cal. 2002), this Court on the record before it, declines to take that step because taking judicial notice of a fact requires that the fact be “not subject to reasonable dispute.” Fed. R. Evid. 201.

36. [13] The United States confronts an untraditional war that presents unique challenges in identifying a nebulous enemy. In earlier times when the United States was at war, discerning “the enemy” was far easier than today. “[I]n war ‘every individual of the one nation must acknowledge every individual of the other nation as his own enemy.”’ Eisentrager 339 U.S. at 772 (quoting The Rapid, 8 Cranch 155, 161 (1814)). The two cases at bar contain nationals from three friendly countries at peace with the United States, demonstrating the difficulty in determining who is the “enemy.”

37. [14] The United States occupies Guantanamo Bay under a lease entered into with the Cuban government in 1903. Agreement Between the United States and Cuba for the Lease of Lands for Coaling and Naval Stations, Feb. 16-23, 1903, U.S.-Cuba, art. III, T.S. 418. The lease provides: While on the one hand the United States recognizes the continuance of the ultimate sovereignty of the Republic of Cuba over [the military base at Guantanamo Bay], on the other hand the Republic of Cuba consents that during the period of occupation by the United States of said areas under the terms of this agreement the United States shall exercise complete jurisdiction and control over and within said areas with the right to acquire … for the public purposes of the United States any land or other property therein by purchase or by exercise of eminent domain with full compensation to the owners thereof. Id. As is clear from this agreement, the United States does not have sovereignty over the military base at Guantanamo Bay.

38. [15] In Harbury, the Court of Appeals referred to Balzac as a situation where foreign nationals were under “de facto U.S. political control.” Harbury, 233 F. 3d at 603. This phrase does not imply that in situations where “de facto sovereignty” might arguably be present, constitutional rights are available to aliens. In making this statement, the Court of Appeals cited to two cases involving Puerto Rico, Examining Bd. of Eng'rs., Architects & Surveyors v. Otero, 426 U.S. 572, 599 n.30 (1976) and Balzac, 258 U.S. at 312-13, and another case involving a special court of the United States that was held in Berlin, United States v. Tiede, 86 F.R.D. 227, 242-44 (U.S. Ct. Berlin 1979). In the two cases involving Puerto Rico, it is undisputed that the United States had sovereignty over the territory.

In the case involving the special court convened in Berlin, the court was a United States court convened in an occupation zone controlled by the United States. Tiede, 86 F.R.D. at 244-45 (“The sole but novel question before the Court is whether friendly aliens, charged with civil offenses in a United States ourt in Berlin, under the unique circumstances of the continuing United States occupation of Berlin, have a right to a jury trial.”). Accordingly, the fact that the panel in Harbury used the phrase “de facto U.S. political control” to describe a category of cases where constitutional rights were provided to non-citizens does not aid Petitioners and Plaintiffs. The cases relied upon by the Court of Appeals in Harbury for this statement do not support the view that where the United States has de facto sovereignty, courts of the United States have jurisdiction to entertain the claims of aliens.

39. [16] While there is dicta in the HCC, opinion which indicates a broader holding with regard to the constitutional rights of individuals detained at the military base on Guantanamo Bay, such dicta in HCC is not persuasive and not binding. HCC, 969 F.2d at 1343. The Supreme Court in Eisentrager, Verdugo-Urquidez, and Zadvydas, and the District of Columbia Circuit in Harbury, have all held that here is no extraterritorial application of the Fifth Amendment to aliens.

40. [1] The court expresses its appreciation to the Public Defender's Office for the Eastern District of Virginia, the United States Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Virginia, and the Solicitor General's Office for the professionalism of their efforts throughout these expedited appeals.

41. [2] This court has previously determined that Esam Fouad Hamdi is a proper next friend. Ham-di I, 294 F.3d at 600 n.1. Two earlier petitions filed by the Federal Public Defender for the Eastern District of Virginia Frank Dunham and Christian Peregrim, a private citizen from New Jersey, were dismissed. Neither Dunham nor Peregrim had a significant relationship with the detainee, and Hamdi's father plainly did. Id. at 606.

42. [3] Persons captured during wartime are often referred to as “enemy combatants.” While the designation of Hamdi as an “enemy combatant” has aroused controversy, the term is one that has been used by the Supreme Court many times. See, e.g., Madsen v. Kinsella, 343 U.S. 341, 355(1952); In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. 1, 7 (1946); Quirin, 317 U.S. at 31.

43. [4] The government has contended that appointment of counsel for enemy combatants in the absence of charges would interfere with a third detention interest, that of gathering intelligence, by establishing an adversary relationship with the captor from the outset. See Hamdi II, 296 F.3d at 282 (expressing concern that the June 11 order of the district court “does not consider what effect petitioner's unmonitored access to counsel might have upon the government's ongoing gathering of intelligence”). That issue, however, is not presented in this appeal.

44. [5] We reject at the outset one other claim that Hamdi has advanced in abbreviated form. He asserts that our approval of his continued detention means that the writ of habeas corpus has been unconstitutionally suspended. See U.S. Const. art. I, § 9. We find this unconvincing; the fact that we have not ordered the relief Hamdi requests is hardly equivalent to a suspension of the writ.

45. Translation Brian Duffett; revision by Jan Christoph Nemitz and Steffen Wirth.

46. [1] In German law the term “serious criminal offence” (“Verbrechen”) is used to denote criminal offences (“Straftaten”) that are punishable with not less than one year of imprisonment. Mitigating (and aggravating) circumstances - as regulated for instance in section 8 subsection (5) - are to be disregarded in this respect (section 12 German Criminal Code). As a result, all criminal offences in the present Draft Code are “serious criminal offences” (“Verbrechen”) with the sole exception of the criminal offences in sections 13 and 14 see the Explanations: B.rticle 1, section 1). Please note that the terminological differentiation between “criminal offences” (“Straftaten”) and “serious criminal offence” (“Verbrechen”) is, for technical reasons, not reflected everywhere in this translation.

47. [1] OJ C 379, 7.12.1998, p. 265.

48. [2] OJ C 262, 18.9.2001, p. 262.

49. [3] P5_TA(2002)0082

50. [4] P5_TA(2002)0367.

51. Under points II 5 and 6 of the Protocol to the Treaty of Amsterdam on the ‘role of National Parliaments in the European Union’.

52. [1] OJ C 295, 20.10.2001, p. 7.

53. [2] Opinion delivered on 9 April 2002 (not yet published in the Official Journal).

54. [1] OJ C 379, 7.12.1998, p. 265.

55. [2] OJ C 262, 18.9.2001, p. 262.

56. [3] P5_TA(2002)0082

57. [4] P5_TA(2002)0367.

58. [5] P5_TA(2002)0449.