No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

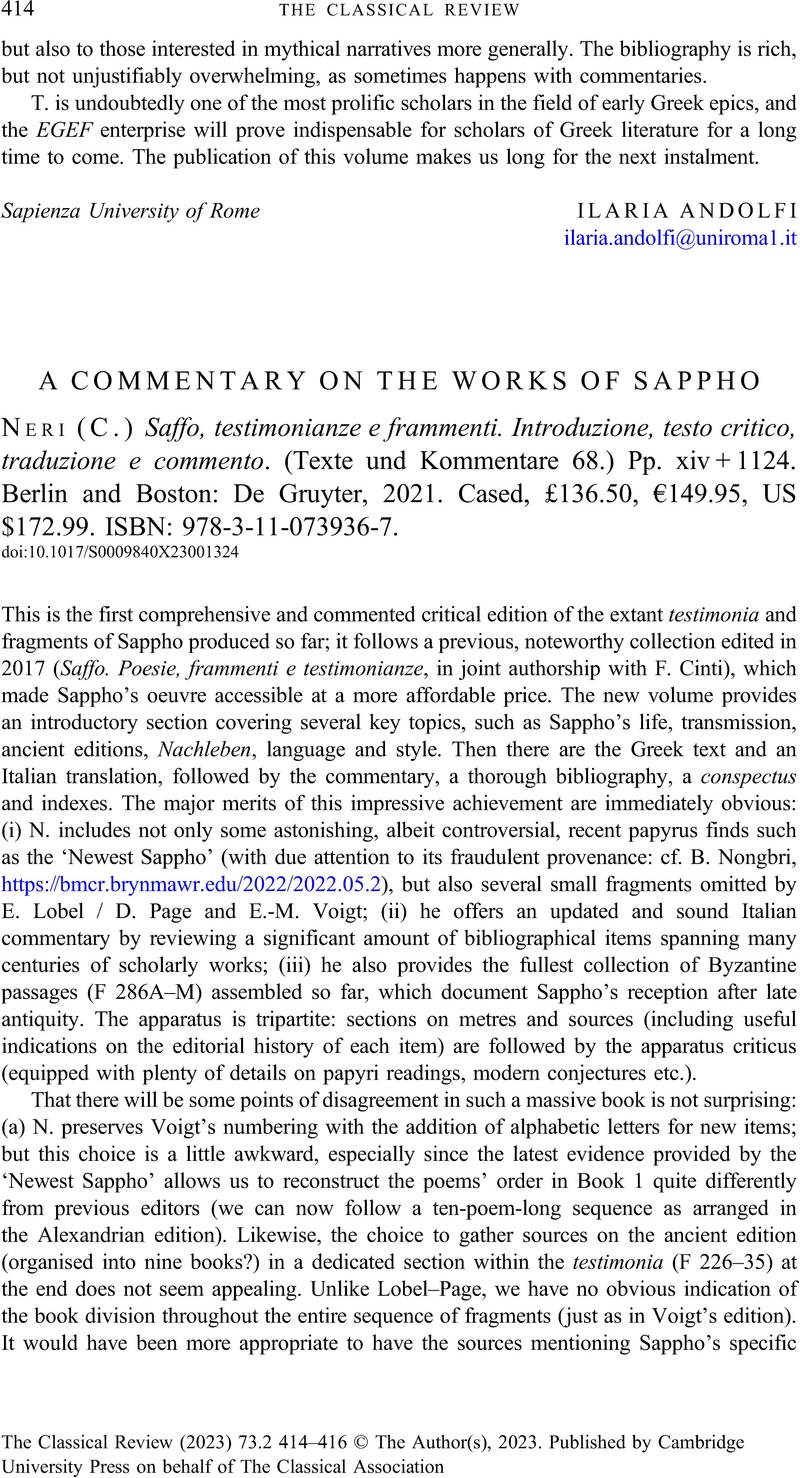

A COMMENTARY ON THE WORKS OF SAPPHO - (C.) Neri Saffo, testimonianze e frammenti. Introduzione, testo critico, traduzione e commento. (Texte und Kommentare 68.) Pp. xiv + 1124. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2021. Cased, £136.50, €149.95, US$172.99. ISBN: 978-3-11-073936-7.

Review products

(C.) Neri Saffo, testimonianze e frammenti. Introduzione, testo critico, traduzione e commento. (Texte und Kommentare 68.) Pp. xiv + 1124. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2021. Cased, £136.50, €149.95, US$172.99. ISBN: 978-3-11-073936-7.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 June 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association