In 1931, the Addo Elephant National Park, a reserve near the city of Port Elizabeth, was founded with a unique zoological purpose: the protection of a single ‘race’ of elephants. The park has since become an important attraction, and is home to several hundred elephants, antelope, carnivora, and thousands of birds. Despite its renown, little has been written on its history. Most accounts depict its genesis as a process of enlightenment: ‘killers’ turned their guns from wildlife and became ‘conservationists’, realizing that nature-protection was ethical.Footnote 1 Jane Carruthers has published a short, nuanced account of the park, which contextualizes it as the first example of a trend in 1930s southern African wildlife-protection of creating sanctuaries protecting particular species.Footnote 2

Behind this success story lies a bloody history of conflict amongst farmers, zoologists, bureaucrats, and elephants. In the 1910s, the ‘Addo Elephants’ roamed the Addo region, ignoring human-inscribed boundaries between farm and bushveld, trampling crops, fences, and occasionally humans in the process. Settler farmers denounced them as ‘vicious’, and demanded they be eliminated, which brought them into conflict with various scientists and metropolitan publics, who were persuaded by a widespread Anglo perception of the elephant as sagacious and peaceful.Footnote 3 Bureaucrats, big-game hunters, and zoologists saw African elephants as potential imperial agents: highly intelligent animals who could be domesticated for labour as in South Asia.Footnote 4 For farmers, they were ‘vermin’ who competed with their livelihood. These conflicts between farmers on the ground, bureaucrats in offices, and zoologists in museums, spawned a twenty-year controversy into the status of these animals as wild or domestic, ‘noble’ or ‘rogue’, oppressed victims, or violent by nature. Ultimately, the founding of the park was shaped by debates about elephant domestication, and fears of elephant degeneration.

Structured into three sections representing different strategies of elephant management – proposals to domesticate the elephants in the 1910s, the decision to eliminate them in 1919, and, finally, to protect them in a game reserve in 1920 – this article seeks to make two contributions to the histories of African conservation, animals, and natural history. First, it adds to growing interest in connecting histories of science and national parks. Although, as Raf de Bont has argued, it is now a ‘cliché’ that conservation ‘should be “science based”’, parks were not always considered scientific spaces.Footnote 5 Scientists were at times actively opposed to African parks on the grounds that they were vast reservoirs of livestock diseases.Footnote 6 As Carruthers has noted, the ‘historiography of nature conservation as science in South Africa…has hardly been touched upon by professional historians’.Footnote 7 This article addresses this lacuna by arguing that the Addo Elephant National Park was founded with explicit scientific racist intentions.

Peder Anker has observed close links between politics and ecology in South Africa in relation to evolutionary theories and the perceived place of human ‘races’ in society.Footnote 8 Saul Dubow, similarly, has investigated how fears of African ‘racial deterioration’Footnote 9 in cities shaped apartheid policies of creating rural ‘native reserves’.Footnote 10 In these spaces, the pastoral African ‘veneer of civilization’Footnote 11 could be ‘protected’ from ‘the urban environment’.Footnote 12 In the 1920s–1930s, Prime Minister Jan Smuts argued that Africa was a ‘human laboratory’ in which racial evolution was an ‘experiment’.Footnote 13 In South Africa, Smuts thought that multiple stages of human ‘evolution’ were preserved and ready for study: from ‘living fossil’Footnote 14 hunter-gatherers, to the developing ‘Transvaal Boer…type’.Footnote 15 Although such racist evolutionary and ecological thinking was typically associated with humans, elephants were also subjected to it.Footnote 16 Racial taxonomy, neo-Lamarckian interpretations of evolution, and fears of degeneration shaped every elephant-management policy taken by the Cape Province. Concepts of racial degeneration justified brutal violence against the animals, and preservationist thinking was mobilized to argue for the creation of the park in ways paralleling the development of segregation legislature and ‘native reserves’.Footnote 17

My second aim is to bring the history of the wild/domestic border into greater conversation with the history of national parks, and the intellectual history of race.Footnote 18 Environmental historians have devoted considerable attention to problematizing the perceived ‘wildness’ of African parks. These spaces were not ‘untouched’ windows onto the prehistoric, but constructed landscapes, deeply entangled with colonial attempts to ‘civilize’ nature, biopolitics, and racism.Footnote 19 Created initially to preserve animals for hunters, and later to entertain tourists, national parks were often established at the expense of indigenous Africans who were forcibly removed from their lands.Footnote 20 Nevertheless, such work has largely operated according to the idea that conservationists predicated the park ideal as a ‘fundamental separation of nature, usually understood as wilderness, from society and culture’.Footnote 21 Animals living within parks have been treated as necessarily ‘wild’, rather than as ‘domestic’, or ‘tame’. Yet the historicization of these actors’ categories reveals that not all advocates of national parks were thinking within these binaries. Parks were not always constructed as wild places in which the domestic was excluded, nor were their animal inhabitants necessarily considered wild.

The Addo Elephant National Park was publicized a ‘wild’ space, but also one where ‘tame’ animals could be viewed in their ‘natural state’, bathing in borehole water and feasting upon cultivated oranges. This does not mean that conservationists placed a veil of wilderness over a constructed landscape,Footnote 22 but that tame, domestic, and wild were not neatly bifurcated actors’ categories, and could co-exist within early twentieth-century parks. Paying closer attention to these categories, along with their inextricably linked concepts of degeneration, race, and evolution, can potentially transform how we think about animal-protection in this period.

But where does the agency of the elephants fit into a story of colonial discourse and environmental alteration?Footnote 23 Farmers, bureaucrats, and zoologists were aware of the capacity of elephants to shape Addo, the danger they posed to humans, and were hesitant to enrage them for fear of retaliation.Footnote 24 For settlers and bureaucrats in the region who struggled to contain their movements, elephant agency was self-evident and limiting it was their primary aim.Footnote 25 The difficulty here is not allowing elephants to ‘speak’, but considering how they trumpeted louder than colonial representations of their behaviour.Footnote 26 Rather than utilizing neo-materialist theory or modern science to ascribe agency to the elephants, I treat agency as an exercise of writing.Footnote 27 Here, I am inspired by Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga's use of the term ‘mobility’ in interpreting the actions of tsetse flies and the knowledge produced in response to their movements.Footnote 28 A key motif in this article is boundary crossing, and I demonstrate how the physical mobility of elephants (roaming, trampling, wallowing) upset colonial understandings of elephant behaviour and transformed ‘Addo Elephant’ into a conceptually mobile category. Not only did it render the Addo region a ‘beastly place’,Footnote 29 but the mobilities of the elephants shaped processes of knowledge production. The animals repeatedly undermined official representations of their behaviour, creating moments of controversy and forcing officials to rethink their categorization as noble beasts, domestic labourers, wild animals, or ferocious rogues.

I

In the 1910s, the area known as the ‘Addo Bush’ was a region of approximately forty-two square kilometres, characterized by dense bush and low rainfall. In the early twentieth century, the bush was thought to be uninhabited by humans and impenetrable: it could only be traversed by cutting it down to clear a path (Figure 1).Footnote 30

Fig. 1. Teams of labourers were required to cut through the bush. Cape Sundays River Settlements (Cape Town, 1918), p. 9.

Despite this, the bush and its surrounds had a long history of amaXhosa, amaFengu and Khoekhoe occupation and dispossession. The bush itself was a site in which the first major conflicts of the fourth Xhosa frontier war took place.Footnote 31 Xhosa leader Ndlambe had a stronghold within the bush, and between 1811 and 1812, a series of skirmishes between his forces and those of Colonel John Graham took place.Footnote 32 By 1869, the colonial government had firm control over the area, and divided the bush into two forest reserves in an attempt to ‘protect’ it from human use.Footnote 33 At the end of the century, although the bush was thought to be unoccupied, between 500 and 1,500 indigenous Africans were still farming in the surrounding valley.Footnote 34 In the 1900s, their independence was steadily eroded: a succession of companies purchased large tracts of land for development, and in 1906, the Strathsomers Estate Company passed a motion forbidding all but white settlers from purchasing their estates. This, according to Jane Meiring, reduced the ‘status of the native’ to ‘that of a labourer entirely dependent upon the European farmer for his living’.Footnote 35 By the 1910s, indigenous Africans had largely been dispossessed of their lands, and were living primarily as tenants on white farms, or as labourers. This longer history of dispossession in the Addo region wrote African land-ownership out of the history of the bush.Footnote 36 Bureaucrats, zoologists, and other white civilians in the 1910s assumed that the bush was a primordial landscape and the home of the elephants ‘from time immemorial’.Footnote 37

Because of its density and the presence of wild elephants, the bush was thought to be extremely dangerous. Even Frederick Selous, the most famous African big-game hunter of the nineteenth century, feared for his safety in the region, and declined the opportunity to shoot an Addo Elephant.Footnote 38 Some African labourers outright refused to enter the bush, while others would only do so if armed.Footnote 39 Surrounding the bush was the Sundays River Valley, a farming district situated between two major cities, Port Elizabeth and Grahamstown (now Makhanda). Unlike the protected bush, the valley had a relatively long history of colonial agriculture. White settlers had been farming in the region from at least 1815,Footnote 40 and since the late nineteenth century, the Cape government and several private developers had attempted to convert the region into a citrus, lucerne, and grain-farmer's paradise. These schemes brought more settlers into the area, and as agriculturalists encroached upon the borders of the bush, farmers encountered herds of aggressive, highly mobile elephants.Footnote 41

In 1913, these farmers complained about the elephants to the Alexandria and Uitenhage magistrates, as well as the Cape provincial administration. These great beasts were crossing boundaries between bushveld and farm, drinking borehole water, trampling fences that impeded their path, and occasionally attacking humans. The four government bureaucrats adjudicating farmers’ complaints, Lewis Mansergh and Don Janisch of the Cape provincial administrator's office, C. W. Chabaud, the magistrate of Uitenhage, and the magistrate of Alexandria, were sceptical of such claims. The idea that elephants were terrorizing the countryside contradicted a widespread perception of elephants amongst metropolitan elites. These great pachyderms were considered docile, intelligent, and co-operative with humans.Footnote 42

From the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, elephants were not thought to be typical pests in the Anglo-world. Elephants fascinated artists, writers, and scientists alike. Wise, compassionate, noble, and humane were some of the adjectives used to describe these great beasts. In Britain and India, as Sujit Sivasundaram has shown, elephants were considered to possess near-human intelligence, human-hand-like trunks, and a penchant for working with humans.Footnote 43 According to Harriet Ritvo, the elephant was often considered one of the most intelligent of all animal species.Footnote 44 This animal, wrote Harvard geology professor Nathaniel Shaler, is ‘innately domesticable, and best fitted by nature for companionship with man, of all our great quadrupeds’.Footnote 45 Being ‘innately domesticable’ was unique: in all other domestic animals except the dog, obedience had been ‘slowly developed by thousands of years of selection’.Footnote 46 Elephants, on the other hand, could supposedly be caught in the wild and easily domesticated.Footnote 47

Despite their putative partiality to humans, elephants were also thought capable of treachery. The noble elephant could transform into a ferocious and pathological ‘rogue’. According to the Oxford English dictionary, this term first entered British naturalists’ vocabularies in traveller James Holman's A voyage around the world (1835). Holman defined the ‘rogue’ as ‘a large male who has been driven from the herd, after losing a contest for mastery of the whole; or a female wandering from it in quest of her calf’.Footnote 48 Unlike other elephants in Ceylon, rogues were ‘cunning and daring’, and ‘a plague and a terror to the neighbourhood in which they prowl’.Footnote 49 By the 1910s, this concept had been directly linked to agricultural depredations. In the 1911 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, rogues were defined as ‘solitary bulls…of a spiteful disposition’ that were ‘permanently separated from their kind’, due to ‘their partiality for cultivated crops’.Footnote 50

As Chris Roche has argued, settlers living alongside elephants in Knysna, South Africa, had a similarly dynamic opinion of the beasts. From the 1850s to the 1920s, the settlers’ conceptions of the elephants shifted between culturally valued animals and pests as economic systems changed. By the 1900s, government bureaucrats thought that the Knysna herd, along with the Addo Elephants, were the last remnants of a population of elephants that once abounded the Cape. Settlers in Knysna who encountered them rejected the idea of elephant sagacity. The Knysna Elephants destroyed their crops and harassed people, and were viewed as vermin that ‘infested’ the forest in the mid- to late nineteenth century.Footnote 51 Despite their protests, Roche argues, as the wildlife-protection movement grew, well-funded game-protection lobbies were founded, and in 1908 elephants were legally classified as ‘Royal Game’.Footnote 52 Under this classification, they could only be hunted with a Royal Game licence and permission from the governor.Footnote 53

Like the Knysna Elephants, as the Addo Elephants crossed the physical borders between farm and veld, they crossed the conceptual margins between Royal Game and vermin. White farmers bitterly resented their classification as Royal Game: the elephants could only legally be shot if they destroyed crops or injured livestock. Yet in this case, the onus of proof lay upon the farmers, and action against an elephant could only be taken after the damage had been done.Footnote 54 Elephant depredations were so severe that farmers insisted that the animals be exterminated.Footnote 55 Yet government officials were unwilling to sanction the death of Royal Game based on this testimony alone. Information was needed from an ‘experienced man’ as to why the Addo Elephants were behaving in ways that undermined existing knowledge of elephant behaviour.Footnote 56

In 1913, Chabaud, the magistrate of Uitenhage, suggested that domestication might prove a means of reconciling the human and elephant conflict. Although African elephants were not usually domesticated, he insisted that this was possible, and worth attempting.Footnote 57 Seeking to confirm his views, he contacted Captain James MacQueen, ‘a gentleman who has done a lot of exploration work in Central Africa and who is well acquainted with the habits of elephants’.Footnote 58 In his initial conversation with Chabaud, MacQueen connected the concept of a rogue elephant with ideas about degeneration. MacQueen was ‘surprised to hear that they are said to be dangerous, as the elephant is inoffensive by nature’ and thought that there ‘must be some “rogue” elephants – degenerates – among them’, who were corrupting the herds.Footnote 59 According to British zoologist Edwin Lankester, degeneration constituted a ‘gradual change of the structure in which the organism becomes adapted to less varied and less complex conditions of life’.Footnote 60 This left the ‘whole animal in a lower condition…than was the ancestral form with which we are comparing it’.Footnote 61 By raiding farms, the Addo Elephants were placed in a ‘lower condition’ by comparison with the sagacious elephants that MacQueen had encountered in Central Africa. According to Daniel Pick, in Britain, France, and Italy, degeneration in humans was a symptom of advancing civilization and social ‘progress’ in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Through alienation from nature, processes of elaboration were being reversed, producing ‘degenerate’ people.Footnote 62 Animals could also fall prey to degeneration. In his 1880 monograph, Degeneration, Lankester argued that any ‘new set of conditions occurring to an animal which render its food and safety easily attained, seem to lead as a rule to Degeneration…as Rome degenerated when possessed of the riches of the ancient world’.Footnote 63

Evidently convinced by such ideas, MacQueen speculated that the cause of roguery was the combination of advancing civilization upon the bush, and a very poor diet (rather than a lavish Roman one).Footnote 64 In his opinion, one means of resolving the conflict would be to plough up the bush, and cultivate ‘sweet potatoes and bananas, of which elephants are very fond’.Footnote 65 If this was done, they would ‘become docile and almost domesticated in time’.Footnote 66 Impressed by his knowledge, Chabaud hired MacQueen to visit Addo and assess the situation.Footnote 67

In August 1913, MacQueen surveyed the bush with two white farmers, and a ‘native guide called Bartman’, and his observations confirmed his speculations.Footnote 68 The Addo Elephants’ mischief was the result of ‘rogue’ elephants who had become ‘vicious’ by exposure to ‘civilization’, and farmers who shot indiscriminately, inevitably wounding them.Footnote 69 Bullet-wounds, he speculated, were key in turning an elephant from sagacious to rogue, because wounded elephants ‘cannot keep pace with the herd, and will end up taking the vagrant occupation of a rogue’.Footnote 70 Human violence had caused the elephant-degeneracy problem. Addo Elephants were not malicious and destructive agents: their mobility was a response to human brutality. They were forced to cross the line between peaceful and pest, as farmers unjustly extended the boundaries between their farms and the bush.Footnote 71

This said, MacQueen acknowledged that elephant mobility needed to be curtailed and thought that benevolent elephant management provided the solution. Like Chabaud, he suggested that the province create an elephant ‘paddock’, and ‘reclaim’ the animals from the wild – domesticate them as had been the norm in India for centuries. MacQueen's ‘reclaiming project’, which may seem antithetical to nature conservation, has a long history in Anglo-imperial thought.Footnote 72 It was posed in an intellectual milieu which bifurcated the sagacious elephant from the rogue and correlated the degeneration of the African elephant with the putative decadence of the African continent from its ‘heights’ of Roman and Carthaginian antiquity.

Although Asian elephants had long been utilized by humans in war and forestry, African elephants had not. In the nineteenth century, naturalists from Georges Cuvier to William Jardine, to Francis Galton had speculated whether the African elephant could be ‘domesticated’, and why no domestication had taken place in Africa for centuries.Footnote 73 As early as 1846, travellers to South Africa such as missionary Henry Methuen had commented on why African elephants had never been ‘tame’. For Methuen, the reasons were cultural: the Africans he encountered (amaXhosa) hunted elephants rather than training them.Footnote 74 Methuen thought elephant hunting was cruel and insisted that the animal ‘be enlisted in the service of man’.Footnote 75 Not only did Indian elephant trainers (mahouts) provide a model of expertise here, but in antiquity, this feat had been accomplished by Hannibal of Carthage, who trained African elephants for warfare.Footnote 76 Like the Carthaginians, settlers could utilize elephants in conquering the environment and its inhabitants, by employing elephants to eat and trample the ‘Fish river bush’, a stronghold of the amaXhosa.Footnote 77

In the mid- to late nineteenth century, such discussions became less about cultural difference, and more about hierarchies of race.Footnote 78 In 1864, president of the Royal Geographical Society, Clements Markham, argued that ‘The inferiority of the African, as compared with the Hindu, is demonstrated by the latter having domesticated the elephant…while the former…has merely destroyed the elephant for the sake of his ivory tusks.’Footnote 79 This view seems to have been widespread, and ex-colonial administrator of Singapore John Crawfurd (1866),Footnote 80 as well as James Tennent (1867)Footnote 81 offered near identical arguments. Others, such as big-game hunter Charles Andersson (1873), and veterinarian John Steel (1885), thought the lack of African elephant domestication was connected with the ‘decline’ of the continent from its ‘heights’ of Roman and Carthaginian civilization.Footnote 82

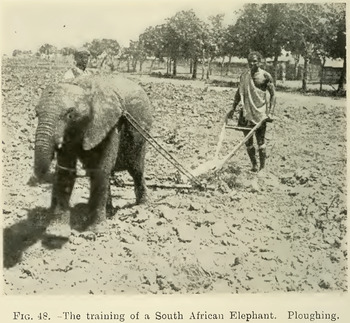

During and after the Berlin Conference of 1884–5, the African elephant became captive to British developmentalist rhetoric: a symbol of, and a tool for, ‘civilizing’ the continent. Numerous British scholars saw the domestication of the elephant as a means of reclaiming the putative glory of North African antiquity. The new ‘superior’ race in British Africa – the Anglo-Saxons – could ‘civilize’ the beast. According to such thinkers, if domesticated, elephants, like Africans, would not degenerate as a result of advancing civilization but stood to benefit: domestication would accelerate their mental evolution. In 1882, Scottish zoologist Andrew Wilson suggested elephants were ‘susceptible of higher development, through domestication’.Footnote 83 Domesticated elephants would benefit colonial survey-teams by serving as steeds that could traverse impenetrable jungles without fear of predators.Footnote 84 These animals could even assist in securing Rhodes's vision of Cape-to-Cairo: British imperialists could train elephants to construct railway lines across the continent (Figure 2).Footnote 85

Fig. 2. Frontispiece to Shaler's 1895 monograph on domestication and civilization. Here an explicit link between the African elephant, civilization, and domestication is drawn. Nathaniel Shaler, Domesticated animals: their relation to man and to his advancement in civilization (New York, NY, 1895). Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by the Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine, <https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.27701>.

For these British imperialists, as well as Chabaud and MacQueen in the Cape Province, the African elephant was thus not a naturally ‘wild’ species that should be left undisturbed. Elephants were powerful imperial agents, who wanted the benefits of ‘civilized life and employment’.Footnote 86 Domestication represented the apex of elephant evolution, and their ‘decline’ in Africa was a result of continental degeneration. While Hindus had successfully domesticated the animals, indigenous Africans had not. This ‘inability’ to master a docile animal that was naturally predisposed to co-operating with humans was taken as evidence of biological African inability to manage nature. To address this, a multispecies civilizing mission was needed: both African humans and elephants could be ‘civilized’ through employment. MacQueen's domestication proposal needs to be viewed within this intellectual landscape – like much of Africa, the Addo Bush was constructed as a backward, wild, and violent space from which the noble and ‘innately domesticable’ elephant could be uplifted.

II

Unlike MacQueen and Chabaud, other Cape provincial bureaucrats were less convinced by nineteenth-century literature on elephant domestication. In May 1914, MacQueen's domestication proposal was debated. Secretary of the Cape provincial administration J. Warrington-Smyth made enquiries into whether the animals could ‘be kraaled and tamed’ by mahouts.Footnote 87 In the course of his enquiries, he realized that this was not economically feasible. Capturing the animals would be difficult because of the dense bush, and the elephants were too expensive as labourers, given their voracious appetite.Footnote 88 Lewis Mansergh, a bureaucrat in the Cape provincial administrator's office drew upon racial science to dismiss the proposal. Economic issues aside, although he recognized that the ‘taming and employment of the elephants for services such as they render to man in India…might open a new era’, there was insufficient Indian labour to perform ‘such an experiment’.Footnote 89 Perhaps concerned about growing anti-Indian sentiment amongst whites, Gandhi's political activism in Natal, and the recent Natal Indian Strike of November 1913,Footnote 90 he also felt it was not a ‘suitable time to import men from India’, but was willing to employ a ‘trustworthy European’.Footnote 91 However, the issue was complicated by a greater labour problem: in the absence of Indian labourers, indigenous South Africans would be required to direct the elephants. Such labourers, in Mansergh's view, were unsuitable for this task:

Handling the animals is not natural to the Native of South Africa, and in his present stage of development it is unlikely that he would readily adapt himself to a calling which, to be successfully proceeded with, one would think would involve some hereditary qualities or, at least traditional if not some natural or national characteristics.Footnote 92

Mansergh's ideas were presented as common-sense but require further analysis. Drawing upon Anglo-imperialist rhetoric which had correlated elephant domestication with hierarchies of civilization, Mansergh suggested that over centuries of co-evolution elephants had learned to respect Indians, and such characteristics were passed down generations in elephant populations. Indigenous South Africans, contrastingly, had never domesticated elephants, and thus were not naturally predisposed to this task. Even if they learned from mahouts, the elephants would not obey them because African elephants had no hereditary characteristics rendering them amenable to African control. In other words, in thousands of years of selection, the relationship between indigenous South Africans and elephants had never been one of master and servant: to Mansergh, indigenous South Africans were biologically incapable of commanding elephants.Footnote 93

In 1914, evidence to the contrary of Mansergh's view already existed. In the 1900s, the Belgian Congo government, with the assistance of Indian mahouts, had established a keddah (elephant training establishment) and trained elephants for timber hauling. Zande peoples were employed as mahouts. Footnote 94 Yet this could also be explained in terms of racial difference: the Azande had ‘Hamatic and Berberine ancestry’, which rendered them ‘natural born mahouts of Africa, the lineal descendants of Hannibal's Nubians’, who had domesticated African elephants in antiquity.Footnote 95 Without any South African ‘natives’ sharing such ancestry, the domestication proposal was discarded by the Cape provincial government. On 3 April 1916, the provincial council of the Cape met to formulate an alternative. Politician Mr Ross was anxious to preserve the elephants, because they were ‘the last surviving remnant in the Southern portion of the Continent of the great African fauna’.Footnote 96 In an attempt to stabilize the status of the Addo Elephants as a protected species, and not a pest, the council resolved to create an elephant reserve. This would allow them to curtail elephant mobility, regulate livestock, and prevent cattle from wandering into the area and ‘possibly irritate the elephants’.Footnote 97 By mid-1916, this proposal had irritated farmers, who complained that the elephants continued to lay waste to their properties. They claimed to be defenceless against the ‘wily brutes’ who had already killed and ‘shockingly mutilated’ several farmers in the area.Footnote 98 If the Cape provincial administration insisted on protecting the Addo Elephants, argued farmer Louis Walton, they should compensate the farmers financially.Footnote 99 In September, thirteen farmers signed a petition demanding the extermination of the elephants.Footnote 100

As the elephants continued to trample crops and fences while moving between bush and farm, this physical mobility forced state officials to reconsider MacQueen's categorization of the species as naturally peaceful. The ‘degenerate’ rogue elephants were too dangerous to be allowed to live, but killing any elephant, they feared, would enrage the other elephants, and drive the entire population to roguery. Wholesale extermination was the only safe course of action.Footnote 101 More importantly, in 1918, the Sundays River Settlement Scheme, an irrigation and town-building project, began attracting farmers from across the world.Footnote 102 The Sundays River settlements could not afford to be destroyed by elephant mobility, and the enclosure of the bush was too expensive to entertain.Footnote 103 Given these new economic constrains, elephant ‘civilization’ was no longer a possibility. Unable to prevent the elephants from crossing physical boundaries between bush and farm, the provincial government could not prevent them from crossing conceptual margins between ‘Royal Game’ and ‘vermin’. On 4 April 1919, the provincial government under Frederic de Waal resolved to exterminate the animals.Footnote 104

One month later, the task was given to famed elephant hunter Phillip Jacobus Pretorius.Footnote 105 Pretorius came at a price but managed to convince the administration that the operation would be profitable. The sale of elephant skeletons and skins for museums, ivory and meat for the market, and the capture of calves for zoos would fetch a total of £9,200.Footnote 106 At the end of May, the hunt began. This was the first step towards physically (but not conceptually) transforming the bush from a wasteland into a semi-domestic space and involved carving roads in a four-by-four grid, and erecting shooting platforms.Footnote 107 Pretorius's hunt was mired with difficulties. He battled to recruit African labour – with an abundance of agricultural jobs in the region, few labourers were willing to risk their lives hunting elephants – and only a group of desperate ex-convicts agreed to work for him.Footnote 108 Although it had been intended as a quick and profitable hunt, the operation dragged on for more than a year, and by mid-1919, zoologists in South Africa, Britain, and the USA began campaigning for the cessation of the slaughter.

While some of these scientists made economic arguments for elephant domestication, most mobilized racial science to articulate their value to zoology. This ultimately became the primary argument for elephant-protection and is directly correlated with the foundation of the park. The South African Association for the Advancement of Science (S2A3) – the largest science society of the country – began pushing a taxonomic argument in favour of their preservation.Footnote 109 In 1900, Paul Matschie, a German zoologist, had compared eighteen elephant specimens, and suggested that African elephants exhibited considerable skull and ear variation relative to their environments.Footnote 110 In his view, they needed to be divided into four regional races.Footnote 111 In 1907, British zoologist Richard Lydekker suggested that further sub-races should be created on the basis of ear-comparison. One of these was what he referred to as the ‘Addo Bush, or East Cape Elephant’.Footnote 112 The Addo Bush elephant was categorized as a unique type (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. A juxtaposition of the ears of the Addo Bush Elephant (p. 383) and West Cape Elephant (p. 385). Richard Lydekker, ‘1. The ears as a race-character in the African elephant’, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (Aug. 1907). Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by the Natural History Museum Library, London, <www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/44963>.

In August 1919, S2A3 issued a statement, drawing upon this taxonomic argument and infusing it with eugenic tropes of ‘dying races’ that were already in circulation across South Africa, but typically applied to humans.Footnote 113 At a meeting in July, J. R. L. Kingon proposed that S2A3 adopt a resolution that ‘this Association views with great regret the decision…to exterminate the herd of Cape elephants, relics of a dying race, now preserved in the Addo Bush’.Footnote 114 Subsequently, S2A3 circulated a memorandum, suggesting that the remaining elephants be preserved in the interests of science, and the ‘young animals…be trained for labour’, while the ‘rogues, should, of course be shot’.Footnote 115 S2A3 suggested that the elephants were not all ‘degenerates’, but a unique race of importance to zoology that could be preserved in peace.

One month later, the Uitenhage and Port Elizabeth farmers associations met to discuss this, and other protests against the slaughter of the elephants. In this meeting, the status of the Addo Elephants as a unique racial type did little to change the farmers’ perspectives. They insisted that the elephants were naturally violent, and that it was a choice between ‘protecting human life or protecting animal life’.Footnote 116 They were also declared to be prone to criminality: farmer Jack Harvey insisted that the elephant was ‘always a thief, and a thief of the worst nature’.Footnote 117 Another farmer, C. H. Mackay, rose in support of Harvey, claiming that the elephants ‘played football’ with his pumpkins.Footnote 118 In his opinion, the ‘scientific value’ of the herd could be preserved by the supply of ‘representative specimens free of cost’ to the Port Elizabeth Museum.Footnote 119 Despite such arguments, the operation was becoming costly. In order to sell the specimens to zoologists, Pretorius agreed to skin the animals, collect their bones and ivory, and make measurements of their morphology. This was time consuming, and nearing the end of October, Pretorius had killed only thirteen elephants.Footnote 120

Although the government had assumed the elephant remains would be valuable, insects and carnivores feasted upon them in the field, and few museums were willing to pay for those that survived. Ivory sales were negligible: almost all the elephants had minute or absent tusks. A mere £390 of £6,100 expenditure was recovered (Figure 4).Footnote 121

Fig. 4. Pretorius supervises his team of labourers as they skin an Addo Elephant in the field. Exact date unknown, 1919–20. P. J. Pretorius, Jungle man: the autobiography of Major P. J. Pretorius (London, 1947), p. 225.

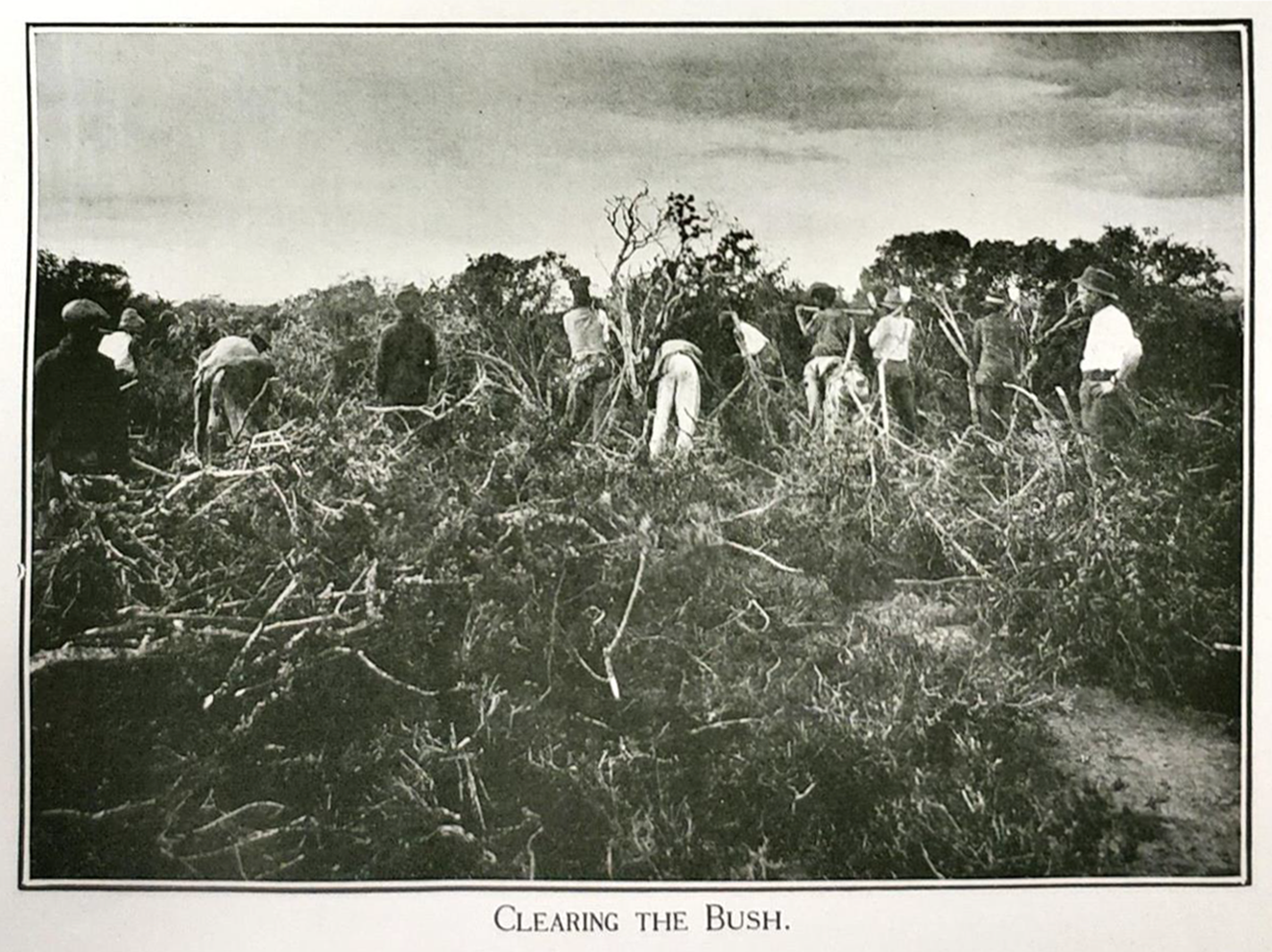

By this point, S2A3's resolution that the elephants were a ‘dying race’ had found traction in North America and Britain, and the government was under pressure to prevent what Science called a ‘zoological calamity’.Footnote 122 Directors of three major South African Natural History Museums, Louis Peringuey (South African Museum), Frederick FitzSimons (Port Elizabeth Museum), and Ernest Warren (Natal Museum), were all vocally opposed to the hunt.Footnote 123 Alwin Karl Haagner, of the National Zoological Gardens, also condemned it as a ‘calamity’ and propagated a plea for the government to reconsider domestication (Figure 5).Footnote 124

Fig. 5. Haagner's field guide, South African mammals: a short manual for the use of field naturalists, sportsmen and travellers (Cape Town, 1920), p. 122, included photographs of an elephant pulling a plough and a cart under the direction of an African labourer in Mozambique. Such photographs served as evidence of the possibility and profitability of domestication. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by the American Museum of Natural History Library, <https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.8933>.

With the elephants worthless as dead specimens, their living value to science provided a new rationale for their preservation. Under pressure from zoologists, the expense of the hunt did not seem justified. Seeking to ‘pocket’ their losses,Footnote 125 the administration renegotiated with Pretorius. The ultimate outcome of the negotiations was that Pretorius would stop collecting specimens, and kill all but sixteen elephants, at a rate of £25 per elephant.Footnote 126 In December 1920, an elephant reserve for the remaining sixteen was created in an attempt to stabilize their categorization as a scientifically valuable species. Under the ward of the province, no humans nor livestock could enter the reserve.Footnote 127 Human and elephant spaces were thoroughly segregated – any human entering the reserve was to be prosecuted, and any elephants leaving their ‘sanctuary’ could be shot.Footnote 128

From 1913 to 1920, although economic concerns were of importance, every decision was justified by recourse to interlinked ideas about race, evolution, civilization, and degeneration. Because indigenous South Africans were considered incapable of domesticating the elephants, the provincial government attempted to segregate the animals in a ‘wild’ space. Facing opposition from farmers, officials subsequently resolved to eliminate the population to protect humans from ‘degenerate’ rogues. Now, protecting the elephants against the wishes of the farmers had been justified according to eugenic concerns about the elephants’ distinct character as a ‘dying race’ (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Pretorius used morphological charts to take measurements for taxonomy and taxidermy. A total of six annotated copies have survived, five with measurements, and this one, with a humorous poem. The author requested that their poem be deposited in the Addo Elephant files, and it appears without any further context in KAB, PAS 3/241. Image reproduced with permission from the Cape Archives Repository, Cape Town. For a brief account of the other five, see M. T. Hoffman, ‘Major P. J. Pretorius and the decimation of the Addo elephant herd in 1919–20: important reassessments’, Koedoe, 36 (1993), p. 29.

III

By the time the reserve was created, the Addo Bush had been physically pacified. The elephant population was a fraction of its former size, a section of the bush had been cut into a grid, and its boundaries were delineated. Yet the monthly reports of elephant caretaker J. J. Millard suggest that the Addo Elephants wanted nothing to do with the reserve.Footnote 129 This, most commentators thought, was the result of a lack of water in the region.Footnote 130 Others offered psychological interpretations. Zoologist Frederick FitzSimons thought the animals were traumatized by Pretorius's devastation of their friends, and no longer wished to reside in a space violated by memories of terror.Footnote 131 Bureaucrats began to recognize that the area designated as wild (the Addo Bush) would never be appealing to animals accustomed to drinking farmers’ water supplies and eating their crops. Throughout the 1920s, the administration continued transforming the bush into a semi-domestic space by erecting boreholes and reservoirs, in the hope that elephants would utilize these water supplies, rather than those belonging to farmers.Footnote 132 Once sufficient water was provided, in 1931, Harold Trollope, a game ranger from the Kruger National Park, and a team of African labourers drove the elephants into the reserve.Footnote 133 Shortly after the drive was complete, the area was declared a national park, with Trollope as its warden.Footnote 134 The elephants, who had once freely roamed the Sundays River Valley, were now to be confined in a small reserve.

At this point, seeking to capitalize upon the zoological curiosity of the elephants, and their close proximity to Port Elizabeth, the Port Elizabeth Publicity Board attempted to transform the park into a tourist spectacle.Footnote 135 The near-impenetrable bush rendered this difficult: nobody could see the elephants, and the animals dared not approach humans. In order to solve this problem, attempts were made to tame the elephants. Between 1931 and 1935, Trollope commenced a ‘feeding experiment’,Footnote 136 in which he tried to train the animals to venture into the open by feeding them oranges, in the hope that they might ‘lose their fear of man’.Footnote 137

Between 1920 and 1935, elephant management in the Addo Bush followed MacQueen's original suggestion for rendering the elephants ‘docile and almost domesticated in time’:Footnote 138 in order to regain their trust, they were given a paddock and offered sustenance. Yet this was never referred to as a domestication project. Instead, the word ‘tame’, once interchangeable with ‘domesticated’, was used exclusively and began to take on a new meaning: the training of elephants to become docile and trusting of humans. By 1934, the elephants were beginning to appear at viewing platforms, eagerly awaiting their food.Footnote 139 In February 1934, the Rand Daily Mail reported that the elephants were ‘getting tamer…and have shown a fancy for the forage’.Footnote 140 A year later, the same newspaper reported that the ‘tame elephants’ were a ‘treat for tourists’, and that the reserve would be opening to the public shortly, in which the ‘comparatively tame’ elephants ‘will amuse visitors by eating oranges at their feeding places’.Footnote 141 In 1959, Jane Meiring dubbed them ‘the pampered pets of the Parks Board’. (Figure 7)Footnote 142

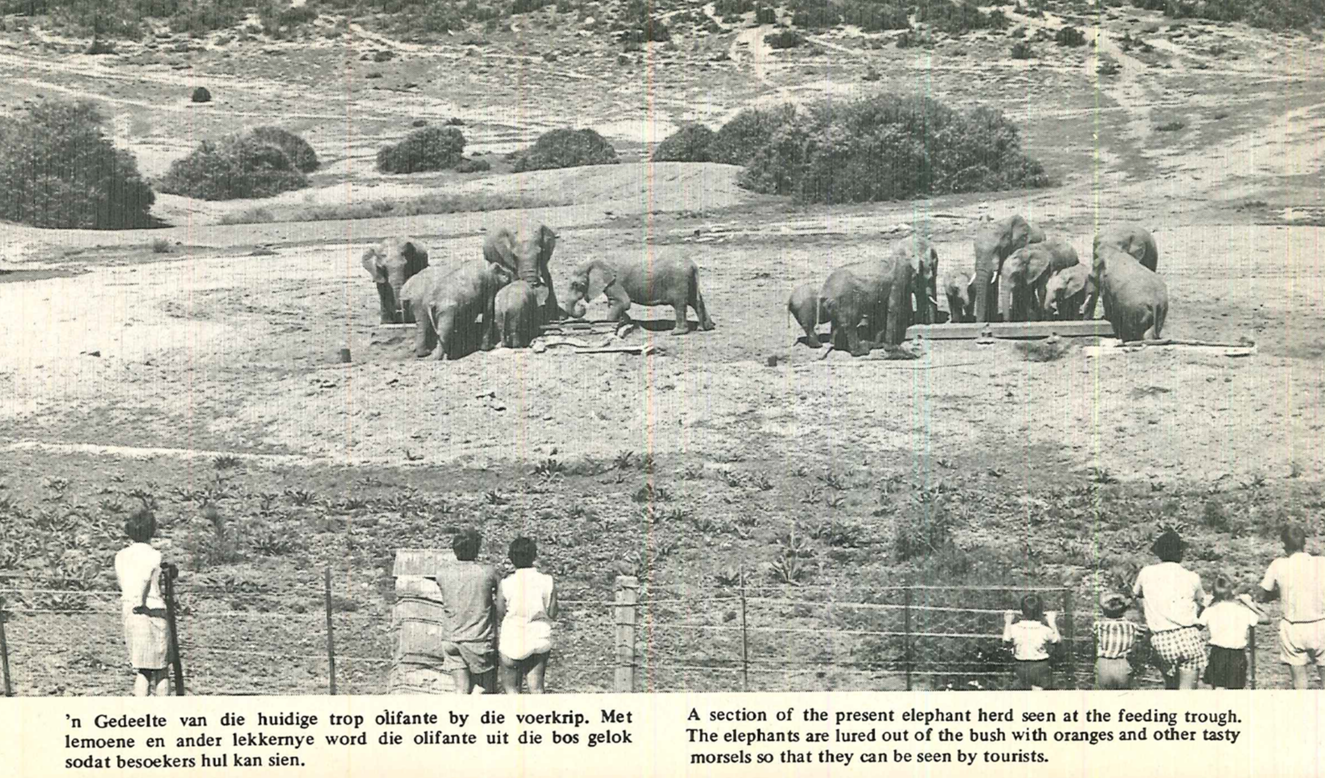

Fig. 7. As late as the 1970s, the elephants were still being viewed feeding on oranges on the outskirts of the park. Visitors were aware of the artificial provision of water. National Parks Board of Trustees, Die Addo Olifante (Pretoria, 1971), insert at p. 30. Reproduced with permission from University of Cape Town Libraries. See also C. S. Stokes, Sanctuary (Cape Town, 1941), p. 378.

Yet despite this physical domestication of the Addo Elephant National Park, and the presence of ‘tame elephants’, the bush retained its conceptual status as a window onto the deep past.Footnote 143 In the 1920s, various South African naturalists, influenced by neo-Lamarckian ideas, argued that the area was of considerable interest to evolutionary biology.Footnote 144 It provided an example of thousands of years of adaptation to a new environment producing a new species (for some), or a degenerate race (for others), through Lamarckian use-inheritance. The greatly diminished or missing tusks, characteristic of the Addo Elephants, was key to their arguments. Perhaps seeking to justify his hunt, Pretorius argued that they were a degenerate ‘family of elephants’.Footnote 145 Based on field-comparisons with a Knysna Elephant he shot, he argued that the elephants had lost their tusks due to inbreeding, and lack of use in the dense and ‘horrible’ Addo Bush.Footnote 146 Zoologist Louis Peringuey of the South African Museum offered a near-identical argument.Footnote 147

These ideas caught on quickly, and from 1925 to the 1930s, proponents of the reserve increasingly stressed its scientific significance.Footnote 148 These publicists argued that the elephants had not degenerated but become perfectly adapted to their environment. In a newspaper article, former minister of lands Deneys Reitz argued that the elephants exhibited no signs of degeneration, as they ‘remained enormous animals’, and did not lag ‘intellectually behind the rest of the elephant family’.Footnote 149 Instead, they had developed unique characteristics on account of hundreds of thousands of years of use-inheritance for the bush, and become a ‘sub-species’.Footnote 150 Elephant tusks, he argued, were needed in forests to strip bark and dig up roots, but not in the Addo Bush. On the contrary, they posed a handicap in ‘tangled and thick’ vegetation, and thus ‘nature’ was ‘eliminating’ their tusks.Footnote 151 Yet, ‘nature’ had compensated by providing the elephants with ‘greater bulk’ to push through the ‘impenetrable thicket which would defeat any other pachyderm’.Footnote 152

Evidently, a tourist spectacle of deep time was incompatible with earlier visions of domesticated elephants on farms. Yet the taming of the elephants did not undermine the idea of ‘natural conditions’. Trollope still referred to the area as one in which elephants lived under ‘natural conditions which were one of South Africa's greatest attractions in the past’.Footnote 153 Likewise, in a seemingly contradictory sentence, T. C. White of the Port Elizabeth Publicity Association argued that the Addo ‘elephants were becoming quite tame’ and that soon tourists would ‘be able to see the elephants in their natural state’.Footnote 154 This seems to pose a paradox: commentators framed the park as a ‘natural habitat’, yet it had been cut into a grid, irrigated, and the elephants were referred to as ‘tame’. Human interference in the area had initially caused the roguery problem, but now promised its solution. These apparent contradictions were never explained, nor problematized by contemporary commentators.

IV

It might be easy to dismiss the construction of the Addo Bush as a site of wilderness as merely artifice: preserving the animals under ‘natural conditions’ was impossible, and this was a compromise. The reality is more complex: the creation of the park was shaped by ideas of domestication and degeneration. In this period, elephants were perceived as a fundamentally domesticable species in Anglo-imperialist thought. In zoological and imperial discourse, elephants sat on the fence between wild and domestic, peaceful and pestilent, and could cross to either side when confronted with ‘civilized’ peoples, just like dogs or ‘wild’ humans. Yet as they crossed physical borders between bush and farm in search of nutrition and fulfilment, the Addo Elephants appeared to resist any stable classification. In response to their mobilities, colonial bureaucrats were repeatedly forced to rethink their categorization of wild or tame, peaceful or pestilent. This boundary-straddling, amidst racist discussions of a wild-continent waiting to be tamed, created the liminal status of the ‘race’, suggesting that the elephants were naturally domesticable and peaceful animals, living in a wild and violent space.

Although the elephants were tamed, they were never ‘civilized’. Due to a series of scientific racist ideas, preservationist and segregationist arguments proved more powerful. With domestication proposals deemed unprofitable or impossible on the grounds of race, scientists gathered momentum for the creation of the park by depicting the elephants as a ‘dying race’ that had adapted to the bush over millennia. Such discourse naturalized the bush as their ancestral home and working elephants could hardly be publicized as a spectacle of the prehistoric. The bush itself had supposedly produced their racial peculiarities and training them for labour would remove them from the very environment to which they were suited.

While elephant domestication was a facet of the nineteenth-century British ‘civilizing mission’, the creation of this park had parallels with twentieth-century segregationist thought in southern Africa. In 1938, Northern Rhodesian bureaucrat Frank Melland argued that the ‘elephant problem’ and the ‘native problem’, meant ‘much the same thing…the attempt to bring an old, indigenous and very different form of life into harmony with our own life and aims’.Footnote 155 In South Africa specifically, ‘native reserves’ were justified as spaces in which Africans were ‘protected’ from the supposedly degenerative effects of urbanization.Footnote 156 To Jan Smuts, South Africa was also a ‘laboratory’ in which racial evolution at different stages could be studied – from hunter gatherers to Boers.Footnote 157 Similar thinking shaped the development of the Addo Elephant National Park: the elephants were confined in a sanctuary which ‘protected’ their ‘race’ from ‘civilization’ and offered a site for the study of elephant racial evolution.

When viewed through racialized lenses of domestication and degeneration, the paradox at play in the Addo Elephant National Park ceases to be a contradiction. Historicizing actors’ categories of ‘domestic’, ‘tame’, and ‘wild’, as well as their connotations of natural and unnatural, reveals that national parks were not necessarily constructed as spaces in which wild animals roamed free of human interference. Taming the elephants was not antithetical to seeing them under ‘natural conditions’: it was a strategy to transform the area into a spectacle of the deep past, and simultaneously to put them on a path towards increasing mental complexity, while protecting them from advancing ‘civilization’. In this space, concepts of tame, domestic, and wild were not bifurcated, but entangled within a network of scientific racist ideas. Wild was considered to be a stage in the evolution of the elephant, as it was in the development of ‘the African’.