Introduction

Although exposure therapy (ET) is an effective treatment and a key element of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for many anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Deacon and Whiteside2019), a significant portion of mental health providers across the spectrum self-report that they either infrequently or never utilize ET in the treatment of anxiety for either youth (Higa-McMillan et al., Reference Higa-McMillan, Kotte, Jackson and Daleiden2017; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Fernandez, Deacon, McNamara, Geffken, McCarty and Striley2018; Whiteside, Sattler et al., Reference Whiteside, Sattler, Ale, Young, Hillson Jensen, Gregg and Geske2016) or adults (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson2004; Freiheit et al., Reference Freiheit, Vye, Swan and Cady2004; Hipol and Deacon, Reference Hipol and Deacon2013; Pittig and Hoyer, Reference Pittig and Hoyer2017; van Minnen et al., Reference van Minnen, Hendriks and Olff2010). Even among therapists who identify as cognitive behavioural therapists, use of ET is low compared with other cognitive behavioural techniques (Freiheit et al., Reference Freiheit, Vye, Swan and Cady2004; Hipol and Deacon, Reference Hipol and Deacon2013; Whiteside, Deacon et al., Reference Whiteside, Deacon, Benito and Stewart2016) and when ET is utilized, clinicians report utilizing less effective forms of ET, such as imaginal exposures rather than in vivo exposures (Hipol and Deacon, Reference Hipol and Deacon2013; Pittig and Hoyer, Reference Pittig and Hoyer2017; Sars and van Minnen, Reference Sars and van Minnen2015; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Fernandez, Deacon, McNamara, Geffken, McCarty and Striley2018).

Given this concern, determining the barriers to the implementation of ET has become of empirical interest in recent years. Many clinicians report concerns that use of ET will cause distress to the patient and exacerbate their symptoms (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson2004; Deacon, Lickel et al., Reference Deacon, Lickel, Farrell, Kemp and Hipol2013; Zoellner et al., Reference Zoellner, Feeny, Bittinger, Bedard-Gilligan, Slagle, Post and Chen2011), that patients will drop out of treatment (Deacon, Lickel et al., Reference Deacon, Lickel, Farrell, Kemp and Hipol2013; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Deacon and Abramowitz2009), worry about legal liability due to exposures (Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Deacon and Abramowitz2009), and a belief that research findings do not translate to clinical practice (Gunter and Whittal, Reference Gunter and Whittal2010; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Deacon and Abramowitz2009). While these concerns are not supported by research (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Wu, Choy and Piacentini2018; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Deacon and Abramowitz2009), endorsement of negative beliefs about ET has been shown to be associated with lower rates of self-reported usage (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Farrell, Kemp, Blakey and Deacon2014; Pittig et al., Reference Pittig, Kotter and Hoyer2019; Reid, Bolshakova et al., Reference Reid, Bolshakova, Guzick, Fernandez, Striley, Geffken and McNamara2017; Whiteside, Deacon et al., Reference Whiteside, Deacon, Benito and Stewart2016), and cautious/suboptimal exposure delivery in experimental and hypothetical situations (Deacon, Farrell et al., Reference Deacon, Farrell, Kemp, Dixon, Sy, Zhang and McGrath2013; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Deacon, Kemp, Dixon and Sy2013; Reid, Bolshakova et al., Reference Reid, Bolshakova, Guzick, Fernandez, Striley, Geffken and McNamara2017), as well as in self-reported actual practice (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Fernandez, Deacon, McNamara, Geffken, McCarty and Striley2018).

The personal characteristics of clinicians have also been identified as a barrier to practising ET. For instance, clinicians’ own anxiety is associated with lower rates of self-reported ET use, less optimal exposure delivery, and larger endorsement of other barriers to ET (Harned et al., Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock and Contreras2013; Levita et al., Reference Levita, Salas Duhne, Girling and Waller2016; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Farrell, Kemp, Blakey and Deacon2014; Reid, Bolshakova et al., Reference Reid, Bolshakova, Guzick, Fernandez, Striley, Geffken and McNamara2017; Scherr et al., Reference Scherr, Herbert and Forman2015). Clinicians may experience anxiety during in vivo exposures (Levita et al., Reference Levita, Salas Duhne, Girling and Waller2016; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Gaudlitz, Plag, Miller, Kirschbaum, Fehm, Fydrich and Ströhle2014) and some therapists worry that they will not be able to effectively tolerate their own distress during this time (Levita et al., Reference Levita, Salas Duhne, Girling and Waller2016). As such, the emotion of disgust may be a particularly salient domain to investigate. Disgust appears to be an important clinical variable, as there is a large body of research linking high proneness to disgust with the development, maintenance and symptomatology of many forms of psychopathology, particularly certain phobias (e.g. blood, animal, health) and contamination fear (a common symptom of OCD; see Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Armstrong and Elwood2017 for a review). Additionally, it has been posited that therapists’ proneness to feelings of disgust may also play a role in the dissemination of ET when considering how frequently disgust is targeted in anxiety and OCD, as exposures may be avoided by clinicians as to not elicit this aversive emotion (Reid, Bolshakova et al., Reference Reid, Bolshakova, Guzick, Fernandez, Striley, Geffken and McNamara2017; Reid, Guzick et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Balkhi, McBride, Geffken and McNamara2017). As a result, therapists may inadvertently model avoidance behaviour through not conducting exposures or approaching exposures in an overly cautious nature (Reid, Bolshakova et al., Reference Reid, Bolshakova, Guzick, Fernandez, Striley, Geffken and McNamara2017; Waller and Turner, Reference Waller and Turner2016).

Clinicians have also reported a lack of formal training as a barrier to utilizing ET (Gunter and Whittal, Reference Gunter and Whittal2010; Reid, Bolshakova et al., Reference Reid, Bolshakova, Guzick, Fernandez, Striley, Geffken and McNamara2017; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Fernandez, Deacon, McNamara, Geffken, McCarty and Striley2018; van Minnen et al., Reference van Minnen, Hendriks and Olff2010). Indeed, individuals who report more extensive training in ET and identify as anxiety specialists are more likely to report utilizing ET in clinical practice (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson2004; Hipol and Deacon, Reference Hipol and Deacon2013; Sars and van Minnen, Reference Sars and van Minnen2015; Scherr et al., Reference Scherr, Herbert and Forman2015). Training interventions for ET in the form of online training or brief workshops have shown promise in decreasing negative attitudes toward ET, increasing knowledge, competence and confidence in conducting ET, and increasing self-reported rates of ET utilization (Deacon, Farrell et al., Reference Deacon, Farrell, Kemp, Dixon, Sy, Zhang and McGrath2013; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Deacon, Kemp, Dixon and Sy2013; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Kemp, Blakey, Meyer and Deacon2016; Harned et al., Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock, Kelly, Zavertnik, Contreras and Danner2014; Jacoby et al., Reference Jacoby, Berman, Reese, Shin, Sprich, Szymanski, Pollard and Wilhelm2019; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Pollard, Szymanski, Berman, Crowe, Rosenfield and Wilhelm2016). While most of these training sessions were open for clinicians of any level of experience (i.e. licensed providers or pre-doctoral trainees), only one was targeted toward novices (i.e. pre-professionals; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Deacon, Kemp, Dixon and Sy2013). There is also concern that the effects of workshops on established providers do not persist over time (Beidas and Kendall, Reference Beidas and Kendall2010; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Crocco, Arnold, Brown, Southam-Gerow and Weisz2015); it is possible, therefore, that such training may be more effective for those earlier in their clinical training.

As such, there have been calls for more early clinical training in treatment modalities such as ET (Callahan and Watkins, Reference Callahan and Watkins2018; Klepac et al., Reference Klepac, Ronan, Andrasik, Arnold, Belar, Berry, Christofff, Craighead, Dougher, Dowd, Herbert, McFarr, Rizvi, Sauer and Strauman2012). The progressive cascading model (PCM; Balkhi et al., Reference Balkhi, Reid, Guzick, Geffken and McNamara2016) is one of the few described methods of practicum training for novices in ET. In the PCM, ET is taught through a hierarchical structure and is based on a ‘train-the-trainer’ model, where individuals play different roles in the delivery of ET based on their comfort, understanding of principles, ability to utilize skills, autonomy, and ability to lead (Balkhi et al., Reference Balkhi, Reid, Guzick, Geffken and McNamara2016). In practice, individuals with limited experience are given lower levels of responsibility which gradually increase as training progresses. In addition, structured supervision is provided and tailored for trainees at each level. Often in traditional training, techniques such as exposures are considered ‘advanced’ techniques, and students do not practise these techniques until their later training (Balkhi et al., Reference Balkhi, Reid, Guzick, Geffken and McNamara2016), which is not ideal for maximizing ET dissemination. Rather, in the PCM, inexperienced individuals are provided early opportunities to build comfort and confidence with ET (e.g. acting as therapy aides or co-therapists) rather than either immediately throwing trainees into the ‘deep end’ or waiting long periods of time before trainees actively experience ET. Establishing early self-efficacy in one’s ability to engage and conduct exposures is essential, as self-efficacy is perceived as an influential variable for therapists to adopt use of ET and evidence-based practices in general (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Schnurr, Biyanova and Coyne2009; Deacon, Farrell et al., Reference Deacon, Farrell, Kemp, Dixon, Sy, Zhang and McGrath2013; Harned et al., Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock and Contreras2013, Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock, Kelly, Zavertnik, Contreras and Danner2014; Pittig et al., Reference Pittig, Kotter and Hoyer2019).

The present study proposed to extend the PCM in a short-term but active, intensive and naturalistic training experience in ET via participation as camp counsellors in a therapeutic summer camp, ‘Fear Facers’. Fear Facers is a 40-hour long, 5-day exposure-based therapeutic summer camp for individuals aged 7 to 16 years with a diagnosis of OCD and/or an anxiety disorder. Camp counsellors acted as ‘exposure coaches’ (see more below) and were, primarily, but not exclusively, undergraduate college students or recent graduates who had never conducted therapy or engaged in any graduate-level clinical practicum. This study aimed to assess whether these pre-professionals broadly interested in mental health and healthcare could build self-efficacy in conducting exposures following participation in this experience. Additionally, this study sought to examine the role of trainee’s perceptions of disgust in this experience, through both its change from beginning to end of camp, as well as its relationship with ET self-efficacy. Disgust sensitivity has been previously demonstrated to decrease during graduate-level training in ET (Reid, Guzick et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Balkhi, McBride, Geffken and McNamara2017), but it is unknown how disgust may influence ET self-efficacy. In the present study, a counsellor’s own feelings of disgust were hypothesized to have a negative influence on ET self-efficacy, considering that the Fear Facers camp placed heavy emphasis on contamination and phobic-related fears (described below).

Method

Procedure

A retrospective review of training records of camp counsellors was conducted, as approved by a university ethical review board (University of Florida IRB201902582). Records of counsellors participating in the two summer 2018 and the two summer 2019 sessions of Fear Facers were obtained. Individuals were recruited to volunteer as counsellors for this program either through word-of-mouth or advertisements on a university web page for those interested in health-related professions. Counsellors completed in-person questionnaires before the training and after completing the week of camp to evaluate the success of the training program. One questionnaire was also administered by email one month following the end of camp. Some counsellors participated in multiple camp sessions; however, only their information from their first camp session with data was utilized. The trainees were reminded during data collection that all responses were de-identified. No compensation was provided.

Participants

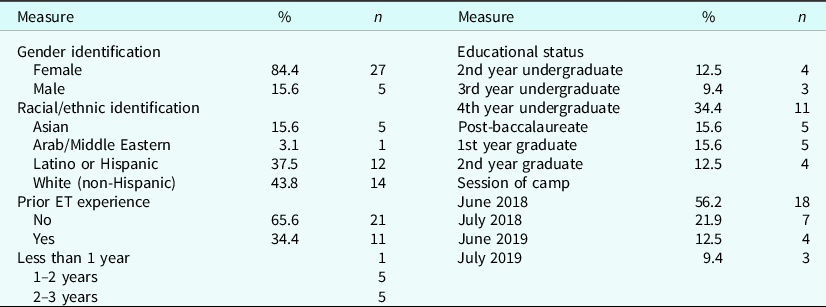

Participants in this study consisted of 32 camp counsellors. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 27 years (mean=21.67, SD = 2). The sample predominantly identified as female (n = 27, 84.4%). Approximately two-thirds of the sample (n = 21, 65.6%) self-reported that they had zero experience with ET. The remaining 11 participants reported having some informal experience with ETFootnote 1 in a volunteer role, with years of experience averaging from 0.25 to 3 years. However, none of the participants had formal clinical experience. The majority of the sample (n = 18, 56.3%) were undergraduate students in a 4-year degree program, five (15.6%) were recent bachelor’s level graduates, and nine (28.1%) were either first- or second-year graduate students in graduate health professions programs. All counsellors reported either being in or completing a psychology or pre-health undergraduate track. Additionally, all but two participants with previous ET experienced acquired their experience through a university clinic specializing in ET. Table 1 summarizes the demographic information described above.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (n = 32)

Prior ET experience was chiefly experience participants had as volunteers within an ET clinic. Undergraduate and graduate majors all fell within the health professions umbrella, most frequently medicine and psychology, as well as some nursing students. Information regarding the exact major for each participant was not available.

Training

Before the beginning of the first day of a camp session, camp counsellors attended training lasting 2–4 hours that consisted of a mix of didactics and active practice in facilitating and conducting exposures in an optimal manner. Topics reviewed in this training include but were not limited to: the symptom presentation of OCD and anxiety, an explanation of how anxiety becomes impairing from a cognitive behavioural perspective, an explanation of the principles of exposure and response prevention, discussion of the theories positing exposure’s mechanism of action, how to design exposures, how to encourage patients to engage in exposures, common myths regarding ET, and techniques to conduct exposures effectively. In addition, counsellors attended meetings prior to the start of camp to review information regarding the camper to whom they had been assigned, as well as to interact with the therapists assigned to the camper.

The clinical structure of camp follows the PCM, a hierarchically structured train-the-trainer model which is described extensively in Balkhi et al. (Reference Balkhi, Reid, Guzick, Geffken and McNamara2016). At all times, at least one licensed psychologist was on-site and available to provide real-time supervision. Each camper was assigned a treatment team consisting of two therapists, typically a combination of a more experienced and less experienced graduate practicum student in psychology or mental health counselling, and a camp counsellor. Camp counsellors served as therapy aides during individual therapy sessions, and throughout the rest of the day served as exposure ‘coaches’ through facilitating the completion of in-camp exposure challenges established during therapy sessions, actively participating in camp activities, and modelling approach and non-avoidant behaviours. Although counsellors were assigned to specific campers, many camp activities involved splitting up counsellors and campers into various groups; thus, counsellors had opportunities to work with several campers. Counsellors were trained to readily seek supervision or assistance at any point in time they felt it was needed. Additionally, supervisors and more advanced therapists regularly checked in with counsellors and their patients, through group therapy, camp activities, or individual encounters.

Each camp day consisted of camper participation in an hour-long individual therapy session, a group therapy session, and a variety of camp games and activities. Camp activities included team building games, as well as artistic, sport, and other performance-related activities and games with creative twists designed to challenge common fears and symptom domains, such as contamination, perfectionism, social anxiety, and phobias. These activities incorporated exposure and response prevention exercises that encouraged campers to ‘face their fears’ in a variety of contexts. Some examples of this include playing ‘hot potato’ with a ‘contaminated’ object, conducting scavenger hunts with exposure goals, playing games in an incorrect or uneven manner, presenting in front of others about odd topics, and participating in a bug zoo demonstration.

Measures

Confidence in Conducting Exposures Scale (CCES)

The CCES (see Supplement 1 of the Supplementary material) was developed by the personnel in charge of training at the Fear Facers camp to assess volunteers’ self-efficacy in conducting ET. The CCES is a self-report scale consisting of nine items. Each item asks participants to rate how confident they currently feel about conducting elements of ET on a 0 to 100 scale, where 0 = ‘cannot do at all’, 50 = ‘moderately certain can do’ and 100 = ‘highly certain can do’. These elements were derived from previous research investigating the training of ET (e.g. Harned et al., Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock and Skutch2011). Example items include ‘design an exposure for a patient’, ‘challenge a patient to participate in an exposure’ and ‘conduct an exposure independently’. A total score was created by averaging all nine items, and the internal consistency for the present sample was found to be excellent (Cronbach’s α=0.98). This measure was administered at pre-camp, post-camp, and 1 month following the end of camp.

Disgust Scale-Revised (DS-R)

The DS-R (Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Williams, Tolin, Abramowitz, Sawchuk, Lohr and Elwood2007) is a psychometrically validated and widely used self-report scale assessing disgust sensitivity in multiple contexts. Disgust sensitivity has been defined as the propensity to experience disgust as aversive (Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Williams, Tolin, Abramowitz, Sawchuk, Lohr and Elwood2007). The DS-R contains 25 items assessed on a 0 to 4 Likert scale. A total average score was used in the present study, with higher scores indicative of higher sensitivity to disgust. Internal consistency was found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s α=0.78). This measure was administered to the counsellors at pre-camp and post-camp.

Contamination Disgust Scale (CDS)

A modifiedFootnote 2 version of the Contamination Cognition Scale (Deacon and Olatunji, Reference Deacon and Olatunji2007), labelled as the CDS in the present study (see Supplement 2 of the Supplementary material), was utilized to assess participants’ estimation of the disgust they would experience if they touched a potentially contaminated item and could not wash their hands. The scale includes 13 items that patients with OCD often associate with germs, including toilet seats, raw meat, and animals. Participants rated their disgust on a 0 to 100 scale, where 0 = ‘not at all disgusted’, 50 = ‘moderately disgusted’ and 100 = ‘extremely disgusted’. A total score averaging all 13 items was calculated, and the scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.92). This measure was administered pre-camp and post-camp.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analysed using the program IBM SPSS 25. Preliminary preparation of the data revealed that 9.9% of all potential pre- and post-camp data points were missing, with Little’s Missing Completely at Random analysis suggesting the data was missing at random (χ2 (30)=26.35, p = 0.657). Multiple imputation with 25 imputations was conducted to impute for missing values of the variables of interest at pre-camp and post-camp, using those variables along with all demographic variables as predictors. Pooled statistics across all 25 imputations are reported when possible, otherwise ranges of statistics across all imputations are presented.

As a preliminary analysis, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to determine whether there was an association between particular demographic variables (i.e. prior volunteer experience with ET, level of education, and session of camp) and the pre- and post-camp variables of interest (i.e. CCES, DS-R and CDS scores). Prior experience with ET was dichotomized as yes (1) or no (0), while level of education was divided into three groups: current undergraduate students, post-baccalaureates, and current graduate students.

A repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (RM-MANOVA) was then conducted to investigate changes in ET self-efficacy and disgust sensitivities from pre- to post-camp. CCES scores, DS-R scores and CDS scores were entered as dependent variables, and time of assessment (pre-camp or post-camp) was entered as the within-subjects factor. Additionally, the interactions between time and the demographic variables found to have a significant multivariate effect from the preliminary MANOVA were also evaluated to account for any confounding relationships. For effect sizes, η2 partial was calculated for multivariate and univariate effects, while Cohen’s d for either between or within subjects was calculated for pairwise comparisons.

A separate RM-ANOVA was also conducted for participants who provided CCES data at pre-, post- and follow-up assessment. Imputed variables were not used for this analysis, as only 14 of the 32 participants provided these data. Bonferroni corrections were applied to these analyses to correct for multiple comparisons.

Lastly, two linear regressions were conducted to test whether ET self-efficacy was related to the disgust variables at either pre-camp or post-camp. The first predicted pre-camp CCES score using pre-camp DS-R and CDS scores, as well as any significant demographic variables. The second was conducted with pre-camp CCES score, post-camp DS-R and CDS scores, and significant demographic variables predicting post-camp CCES score.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The first MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate effect for prior ET experience on the pre-camp and post-camp variables across all 25 imputations (Pillai’s trace≥.596, F 6,20≥4.908, p ≤ .003). Level of educational attainment (Pillai’s trace≤.493, F 12,42≤1.112, p ≥ .376) and session of camp (Pillai’s trace≤.482, F 18,66≤0.722, p ≥ .777) did not have significant multivariate effects across all imputations. As such, the subsequent RM-MANOVA was conducted using the interaction between time and prior ET experience, and prior ET experience was included as a predictor for both sets of regressions predicting CCES scores.

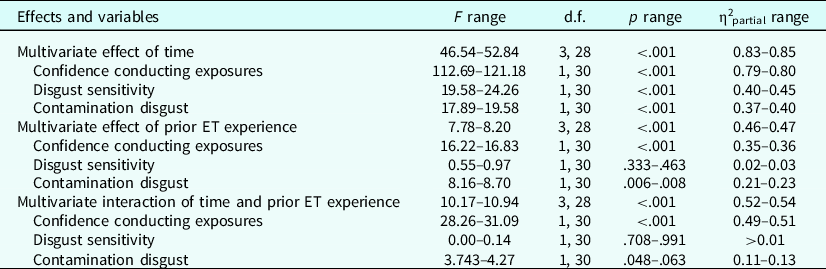

Change in variables

The RM-MANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time on the dependent variables, collectively, for all 25 imputations (all p < .001), with η2 partial values ranging from 0.83 to 0.85. Additionally, there was a significant multivariate interaction between time and prior ET experience for all 25 imputations (all p < .001), with η2 partial values ranging from 0.52 to 0.54. Multivariate and univariate effects are summarized in Table 2 and estimated marginal means for each variable at each time point are presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Model statistics of RM-MANOVA tests

Based on 25 imputations. Time and time×prior ET experience entered as within subjects’ factors; prior ET experience entered as between subjects’ factor Pillai’s trace for each multivariate effect is equivalent to its η2 partial value.

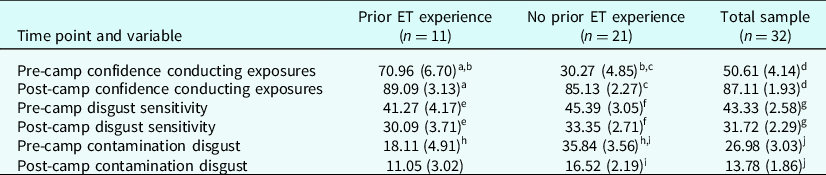

Table 3. Estimated marginal means

Pooled mean (SE) statistics based on 25 imputations. All variables can range from 0 to 100. Variables with the same superscript letter are significantly different from each other at p < .05.

Self-efficacy conducting ET following training

Both the main effect of time (F 1,30≥112.69, p < .001, η2 partial≥0.79) and the interaction of time and prior ET experience (F 1,30≥10.17, p < .001, η2 partial≥0.49) were significant for CCES scores across all imputations. Overall, ET self-efficacy increased by 36.5 points (72% increase, p < .001 for all imputations) from pre-camp to post-camp, corresponding to a pooled Cohen’s d of 1.86. Across all imputations, pairwise comparisons revealed significant increases in ET self-efficacy for both those with prior experience (d = 1.19, p < .005) and those without prior experience (d = 2.92, p < .001) from pre-camp to post-camp. Those who had prior ET experience also reported significantly higher pre-camp ET self-efficacy than those without (d = 1.23, p < .001); however, there was no significant difference between the two groups in post-camp ET self-efficacy (d = 0.27, p > 0.3).

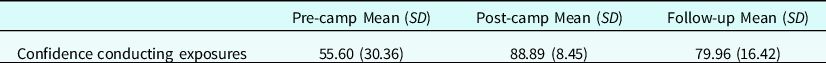

The RM-ANOVA for the participantsFootnote 3 providing pre-, post- and follow-up data revealed a statistically significant effect of time (F 1.13,15.81=26.22, p < .001, η2 partial=0.70). Pairwise comparisons revealed the following differences in ET self-efficacy at each time point; post-camp was significantly higher than at pre-camp (d = 1.42, p < .001), post-camp was significantly higher than at follow-up (d = 0.84, p = .023), and follow-up was significantly higher than at pre-camp (d = 1.43, p < .001). Table 4 summarizes these findings.

Table 4. Confidence conducting exposures at three time points

n = 14, all significantly differ from each other at p < .05. Of these participants, six had prior ET experience.

Disgust sensitivity following training

The univariate effect of time was significant on DS-R scores for all 25 imputations (F 1,30≥19.58, p < .001, η2 partial≥0.40), but the interaction between time and prior experience was not (F 1,30≥0.00, p ≥ .708, η2 partial≥0.00]. Pairwise comparisons revealed that on average across all imputations, mean disgust sensitivity decreased by 11.61 points (27% decrease, p < .001 for all imputations) from pre-camp to post-camp, corresponding to a pooled Cohen’s d of 0.84. Disgust sensitivity did not significantly differ between those with and without prior ET experience at either time point.

Contamination disgust following training

The main effect of time for CDS scores was significant across all 25 imputations (F 1,30≥17.89, p < .001, η2 partial≥0.37). The interaction between time and prior ET experience on CDS scores reached significance at α=.05 for two of the 25 imputations but approached significance in all other imputations (F 1,30≥3.743, p ranges .048 to .063, η2 partial≥0.11). Across all participants, the pooled decrease in contamination disgust was 13.2 points (49% decrease, d = 0.80, p < .001 for all imputations). For those without prior experience with ET, contamination disgust significantly decreased (p < .001 for all imputations) with a pooled Cohen’s d of 1.17. There was not a significant decrease in contamination disgust for those with prior ET experience (pooled d = 0.43, p < .16 for all imputations). While those without prior ET experience reported higher contamination disgust at pre-camp (pooled d = 1.09, p < .001 for all imputations), there was no significant difference between the two groups at post-camp (pooled d = 0.55, p < .15 for all imputations).

Predictors of ET self-efficacy

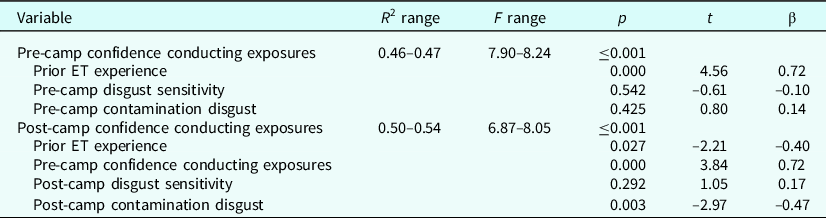

Table 5 summarizes the regressions predicting pre-camp and post-camp ET self-efficacy. The imputed models for the first regression explained 46–47% of the variance in pre-camp ET self-efficacy (F 3,28≥7.90, p < .001). In this first model, having prior experience with ET was a significant positive predictor of ET self-efficacy (pooled β=0.72, pooled p < .001), while pre-camp disgust sensitivity (pooled β=–0.10, pooled p = 0.542), and pre-camp contamination disgust (pooled β=0.14, pooled p = 0.425) were not.

Table 5. Regression statistics

R 2 and F values are the minimum and maximum statistics observed for the 25 imputations. β and t are pooled statistics of the 25 imputations.

In the second regression, between 50 and 54% of the variance in post-camp ET self-efficacy was explained across 25 imputations (F4,27 ≥ 6.87, p < .001). Pre-camp ET self-efficacy was a significant positive predictor of post-camp ET self-efficacy (pooled β=0.72, pooled p < .001). Additionally, having prior experience with ET before participating in the camp and post-camp contamination disgust were both significant negative predictors of post-camp ET self-efficacy (pooled β=–0.40, pooled p = .027, and pooled β=–0.47, pooled p = .003, respectively). Post-camp disgust sensitivity was not a significant predictor in the model (pooled β=0.17, pooled p = .292).

Discussion

Consistent with hypotheses, participants’ feelings of self-efficacy conducting ET significantly increased between the beginning of the training and the end of the summer camp, with a large effect size. This increase in self-efficacy was especially pronounced in individuals who reported they had no experience conducting exposures prior to the camp. Additionally, among a subset of participants surveyed one month following the end of the camp, average self-efficacy with ET remained above levels observed before the camp, although below levels observed immediately after the end of camp. Taken together, these findings contribute to research suggesting that brief training experiences that emphasize experiential learning, tiered supervision, and a train-the-trainer model can increase feelings of self-efficacy in performing ET or other forms of evidence-based practice, which has been linked with an increased likelihood of using the treatment (Harned et al., Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock and Skutch2011; Harned et al., Reference Harned, Dimeff, Woodcock, Kelly, Zavertnik, Contreras and Danner2014; Pittig et al., Reference Pittig, Kotter and Hoyer2019). These previous investigations, however, have utilized samples of currently practising clinicians, whereas the present study investigated individuals who had never conducted therapy or independent clinical work. There are several advantages to targeting this population.

First, providing early opportunities for individuals to gain experience conducting ET is associated with an increased likelihood of utilizing this treatment in the future (Broicher et al., Reference Broicher, Gerlach and Neudeck2017; Pittig and Hoyer, Reference Pittig and Hoyer2017). In general, clinicians directly report that early training experiences are highly influential in their decision to utilize certain psychotherapeutic practices (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Schnurr, Biyanova and Coyne2009). Additionally, younger, more inexperienced individuals are more open to undergo training in evidence-based modalities and ultimately adopt the treatment (Beidas and Kendall, Reference Beidas and Kendall2010; Pittig and Hoyer, Reference Pittig and Hoyer2017). Thus, from a developmental lens, early experiences – particularly experiences prior to graduate-level training – with empirically supported treatments such as ET can be important in establishing a professional identity in which evidence-based practices are viewed as favourable and feasible to conduct in actual practice. Drawing from vocational theory, experiences like these can serve as opportunities to build interest in career choice through development of career self-efficacy (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Park, Yang, Lee, Lee and Lee2012). Specifically, this kind of training serves as a method to affect both process career self-efficacy (which refers to actively engaging in activities to make decisions on a career) and content career self-efficacy (referring to self-efficacy performing in certain fields, like exposure therapy in this case; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Park, Yang, Lee, Lee and Lee2012).

An additional advantage to this population is that it can potentially result in interdisciplinary dissemination of ET. Providing hands-on training in how to combat anxiety for those who may enter medicine, nursing or other health fields can be valuable in enhancing their treatment conceptualization and recommendations moving forward (Reid, Guzick et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Balkhi, McBride, Geffken and McNamara2017). Calls to disseminate ET to lay-providers or non-mental health specialists have already been made, and findings suggest it can be effectively taught (Gega et al., Reference Gega, Norman and Marks2007; McDonough and Marks, Reference McDonough and Marks2002).

In examining the CCES scores, one may be surprised by the high average level of ET self-efficacy following the end of camp (86.5 out of a possible 100) for a group of relative novices. Certainly, there is evidence to suggest that providers may over-estimate their own capabilities or competence with psychotherapeutic treatments (Waller and Turner, Reference Waller and Turner2016). There is also the possibility of a ceiling effect of the CCES measure. However, it may also be attributable to the extensive clinical support provided to the counsellors through the PCM. Research has previously described the important role of organizational and environmental factors on feelings of self-efficacy conducting evidence-based practice (Beidas and Kendall, Reference Beidas and Kendall2010; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Nicholson and Sanders2011). Through the PCM, counsellors were able to take limited responsibility and heavily lean on experienced therapists or supervisors, yet were also given numerous opportunities to directly experience and even administer the delivery of exposures, which was associated with greatly enhanced self-efficacy with ET even one month following camp. With that said, this increase in self-efficacy is heavily contingent on contextual factors, as participants’ rating of self-efficacy is a function of their specific role in camp, so it is unknown if this would generalize to exposure therapy in other contexts.

Even amongst pre-professionals, those who had some level of ‘experience’ with ET came into the training experience with much higher feelings of exposure self-efficacy. Rather than exclude these individuals, these counsellors were included in the analyses because the PCM is designed to meet trainees where they are at in terms of their own capabilities (Balkhi et al., Reference Balkhi, Reid, Guzick, Geffken and McNamara2016), which is in line with conceptualizations that training should become increasingly complex as individuals progress (Callahan and Watkins, Reference Callahan and Watkins2018). Counsellors entering with some experience were often assigned campers with more severe symptoms and more complex presentations or were given more responsibilities in setting up or leading camp-related activities. This may be reflective in that, while ET self-efficacy did increase amongst those with prior experience, post-camp self-efficacy did not significantly differ from those without prior experience. More experienced individuals may have had a different conceptualization as to their role in delivering ET, reflective of a developmentally tailored experience.

Both counsellor global disgust sensitivity and contamination disgust decreased with time, although the decrease in contamination disgust was only significant in those without prior ET experience. This is probably due to a combination of a floor effect on the CDS – those with prior ET experience already scored fairly low on this measure – and constraints related to the small sample size for the prior ET experience group (n = 11). Disgust sensitivity was previously observed to decrease across a practicum experience in ET following the PCM (Reid, Guzick et al., Reference Reid, Guzick, Balkhi, McBride, Geffken and McNamara2017), and has also been shown to reduce during ET for individuals independently of their anxiety (Smits et al., Reference Smits, Telch and Randall2002). Of note, declines in disgust following exposure tend to be situation specific as opposed to global (Consedine et al., Reference Consedine, Yu and Windsor2013; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Armstrong and Elwood2017; Smits et al., Reference Smits, Telch and Randall2002), so perhaps these changes in disgust are contextualized to the setting of the camp. This may have been accomplished by the opportunities that counsellors had to model disgust-related exposures, as well as modelling they witnessed from more advanced trainees.

Moreover, in this study disgust sensitivity broadly did not predict ET self-efficacy; however, lower contamination disgust after camp was associated with higher post-camp ET self-efficacy. This may be because the camp’s group activities tended to target contamination, phobic, and social fears, rather than obsessions and compulsions related to harm, symmetry or taboo thoughts. For example, counsellors and campers were instructed to not wash their hands while at camp except under specific circumstances, and many activities were designed to elicit feelings of being potentially contaminated. Based on their camp experience, pre-professionals in this study may have been more inclined to think that exposures typically involve contamination and may have been more likely to believe there is a stronger relationship between ability to deliver ET with how disgusted they feel with possibly contaminated objects as opposed to more broad disgust sensitivity. On the other hand, it is possible that specific feelings of disgust are more pertinent to beliefs of being able to effectively conduct ET than a more general disgust sensitivity. A study by Holstermann et al. (Reference Holstermann, Grube and Bögeholz2009) found that feelings of task-specific disgust moderated changes in perceived self-efficacy related to that task. Like this study, disgust did not seem to impact self-efficacy prior to the start of the task but did impact participants’ ratings of self-efficacy after the task had begun (Holstermann et al., Reference Holstermann, Grube and Bögeholz2009). Results from Randler et al. (Reference Randler, Hummel and Wüst-Ackermann2013) also suggest that situation-specific disgust may negatively impact feelings of competence.

This possible relationship between disgust and feelings of self-efficacy appears to be consistent with other research regarding disgust’s impact on vocational development. Disgust sensitivity has been found to be associated with certain vocational decisions, such as choosing medicine over other healthcare professions (Consedine et al., Reference Consedine, Yu and Windsor2013), or being more willing to engage in direct volunteer activities over indirect participation (Hamerman and Schneider, Reference Hamerman and Schneider2018). Randler and colleagues (Reference Randler, Hummel and Wüst-Ackermann2013) and Holstermann et al. (Reference Holstermann, Grube and Bögeholz2009) suggested that feelings of disgust relating to academic activities may negatively influence intrinsic motivation, which may also apply in a context such as ET. Notably, average levels of disgust sensitivity and contamination disgust in this study were below the midpoint of the DS-R and CDS, respectively, at pre-camp and post-camp, thus, it is possible that individuals interested in participating in ET may present with lower or more easily adjusted state or trait disgust, but the present study cannot provide explicit support for that hypothesis.

In considering these findings, it is also important to note the limitations of the present investigation. This study did not have a control group and was not experimental in nature, thus statements regarding the ‘effect’ of this training must be tempered. That stated, this study possesses ecological validity due to the examination of an actual clinical event (i.e. clinical care during the Fear Facers camp) and the scalability and replicability of the PCM due to its focus on experiential learning with a hierarchical structure with tiered supervision (Balkhi et al., Reference Balkhi, Reid, Guzick, Geffken and McNamara2016). However, the sample size for the present study was limited, there was heterogeneity in participants’ education levels and majors, and there was certainly selection bias due to use of a convenience sample. Additionally, two of the three main outcome measures were created by the authors for the purpose of this training, and thus have unestablished indices of reliability and validity. Other important measures of training outcome and impact such as satisfaction with utilizing ET, desire to utilize ET in the future, and directive measures of ET knowledge and competence were not included, nor was extensive longitudinal data gathered. As was observed, ET self-efficacy at 1-month follow-up decreased relative to immediately after camp, so it is unknown whether the gain in ET self-efficacy observed would remain over a longer period of time. It is also important to note that while feelings of competence utilizing a therapy are often associated with utilization rates, this is far from a perfect relationship (Beidas and Kendall, Reference Beidas and Kendall2010). In this training experience, individuals were only assessed following the initial didactic training and after the end of camp, but not following the end of didactic training. As such, the relative effect of the pre-camp training versus the actual camp experience on the variables of interest is unknown. The information that was collected was not linked to patient outcomes, which can be problematic given that change in therapist variables such as self-efficacy have not always corresponded with patient change (Beidas and Kendall, Reference Beidas and Kendall2010), although it is important to note the preliminary clinical data for patient outcome in Fear Facers is promising (L. Lazaroe et al., under review).

Future research should include experimental research utilizing larger, diverse samples, psychometrically validated questionnaires, and longitudinal data collection to verify the efficacy of the PCM, both in terms of trainee development as well as patient satisfaction and outcome. Use of control interventions (e.g. didactic instructions without hands-on experience) would also increase confidence in the efficacy of this training model. Additionally, more research is needed to directly identify the benefits of receiving early hands-on experience with evidence-based practices like ET, such as its role in vocational selection. The role of clinicians’ feelings of disgust surrounding exposures warrant further investigation, as it is unknown if disgust is influential for more experienced clinicians. Clinician characteristics, particularly disgust proneness, should be holistically conceptualized and considered for their possible influence in treatment outcome.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a time-limited training experience that follows the principles of a live tiered-supervision model with modelling from more advanced clinicians and a hierarchical structure that provides incrementally more responsibility with increased competence is a promising method to enhance feelings of self-efficacy conducting ET, even amongst a group of pre-professionals with limited ET experience. In turn, there is potential that establishing early self-efficacy in ET may lead to increased dissemination of this efficacious treatment. While more research is needed on how therapist characteristics influence utilization of evidence-based practice, particularly disgust, we hope that these findings help guide future dissemination work and training efforts, with the goal of increasing the availability of evidence-based services that leads to more patients experiencing symptom decline and improvement of life.

Key practice points

-

(1) Pre-professionals can establish self-efficacy conducting CBT techniques following experiential training.

-

(2) Sensitivity to disgust may be an important clinician level variable to consider in the practice of exposure therapy.

-

(3) Providing early and enriched training experiences with CBT techniques may aid to improve dissemination.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X22000010

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Ryan McCarty: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Danielle Cooke: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (lead), Project administration (equal), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Lacie Lazaroe: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (equal), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Andrew Guzick: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Andrea Guastello: Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Sierra Budd: Data curation (equal), Investigation (supporting), Project administration (equal), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Seth Downing: Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Ashley Ordway: Investigation (equal), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Carol Mathews: Resources (lead), Supervision (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Joseph McNamara: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statements

All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. This study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (IRB201902582).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, R.M., upon reasonable request.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.