Introduction

This article sets out a framework for studying the power of secrecy in security discourses. More specifically, this article makes the case that to understand the complex workings of power within a security discourse, the political work of secrecy as a multilayered set of practices needs to be analysed. Taking inspiration from the work of Karma Lochrie who argues that rather than focusing on ‘the secret’ as the locus of power, studying ‘what covers secrecy’ and the particular social context of these practices offers insight into the ‘power relations that surround and give meaning’ to a discourse’.Footnote 1 As Eve Sedgwick suggests, secrecy can be ‘as performative as revelations’ and may be as multiple and follow different paths as the knowledge it works to obscure.Footnote 2

To date, this interplay between secrecy and security has been explored within security studies most often through a framing of secrecy and security as a ‘balancing act’, especially concerning executive power and intelligence agencies. Within this literature, secrecy and security are uncontested and self-evident, secrecy and revelation are binary opposites, and excesses of either secrecy or revelation are a ‘corruption’ that damages either democracy or national security.Footnote 3 Increasingly, however, the co-constitutive relationship between secrecy and security is the subject of scholarly explorations. Across critical geography, anthropology, sociology, history, and cultural studies, a transdisciplinary field of ‘secrecy studies’ has emerged that offers insight into the complex interconnections and the generative powers of secrecy.Footnote 4

As this article contends, secrecy can be understood therefore as a nested set of practices, a composition that obscures, hides, and even makes illegible as a central part of the act of power. Beyond a binary and linear spatial conception of secrecy as inside/outside, covered/uncovered, concealed/revealed, enclosed/exposed, security discourses may rely on multiple layers of secrecy practices with associated meaning-making, an arcanum that includes geospatialities of secrecy, techniques and technologies of secrecy, cultures of secrecy, and spectacles of secrecy (see Tables 2–5). As argued here, the result of these different layers is the production and centring of several different secrecy subjects that help to make sense of war. Security subjects within a discourse must be enrolled or hailed into subject positions. This interpellation, however, rests on a co-constitutive relation between these subjects and secrecy and the extent to which certain subjects are permitted or denied different secrecy practices.Footnote 5 Secrecy is therefore connected to the personal, embodied, raced, gendered, sexed, abled, and everyday ways of being and structures of knowing that make possible the broader international and transnational dimensions of power.Footnote 6 In other words, to study the social and political power of secrecy directs ‘attention to the practices of concealment that cultures exert upon different subjects and in different ways’.Footnote 7 These practices produce not only the ‘[c]arefully scripted absences and silences’Footnote 8 of redactions, radio silences and cover-stories that state actors use to justify war, but also a composition and layering of ‘insider’, ‘stealthy’, ‘quiet’, and ‘alluring’ subjects as well.

Therefore, taking inspiration from Critical Security Studies’ engagement with assemblage theory,Footnote 9, how might a turn to composition offer new insight? As this article proposes, the term and practice of composition looks both at the content, form, and relations within a text – an approach more common in rhetoric and visual studiesFootnote 10 – while also drawing attention to layering as a knowledge-making practiceFootnote 11 in ways underexamined in security theory's engagements with assemblage theory. A multilayered composition, or an ‘assemblage of assemblages’,Footnote 12 entails a ‘flow’, route or ductus, by which it ‘leads someone through itself’.Footnote 13 Layering also offers a means to explore the complex and dynamic interactions between the everyday and the global. As Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani argues, we can imagine individuals layering meaning onto experiences in dynamic, concentric, and interconnected ways and in connection with the larger world and their worldviews.Footnote 14

Most importantly, compositions entail layers of meaning and practices that are constituted through their blanks, silences, absences and gaps, not as an enigmatic gap into which meaning can be poured, but tied to a specific flow of the composition and therefore to specific meaning and knowledge-making efforts.Footnote 15 The conception of social space as layered is therefore complicated further by attention to the ways in which layering works as obscuration through secrecy. As Susan Star argues, layering is a knowledge-making practice that includes partial visibilities. Meaning is made in part through the interplay of the partial visibility and invisibilities between layers, and ‘a layering process, which both complicates and obscures’.Footnote 16 Multilayered compositions are therefore also made meaningful through the meaning-making potentials of invisibilities, negative space, silences, gaps, and absence about which there is a growing literature.Footnote 17

Taking layers, and in particular multilayers, that work to obscure seriously, as part of compositions within security discourses, therefore invites a way to think through the political work that covering secrets does within security discourses. Studying a security discourse as a multilayered composition enables a study of the way that everyday secrecy is experienced, sensed, narrated, negotiated, and woven into lives; to understand how people ‘know secrets’, how knowledge of secrets is personal while also global, and how secrets also make people. To disappear a body, a nuclear submarine, a file, tetrabytes of data, or a succession of US military bases relies on a multilayered composition for keeping secrets, what I call an arcanum.

Using the US ‘shadow war’ as an empirical case study, adding to a growing body of literature that explores the power and politics of a second decade of the Global War on Terrorism (GWoT),Footnote 18 and in particular conducting a close reading of a set of key memoirs associated with the rising practice of ‘manhunting’ in the GWoT, the legitimising and meaning-making practices of this multilayered composition are explored. This article therefore also responds to the methodological challenge of studying secrecy by focusing on the public life of these secrets, such as the details surrounding the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, and how its covering over was detailed and narrated.Footnote 19 In staying with ‘what covers the secret’,Footnote 20 rather than on what is concealed and revealed, the series of interconnected and layered secrecy practices become the site of power.

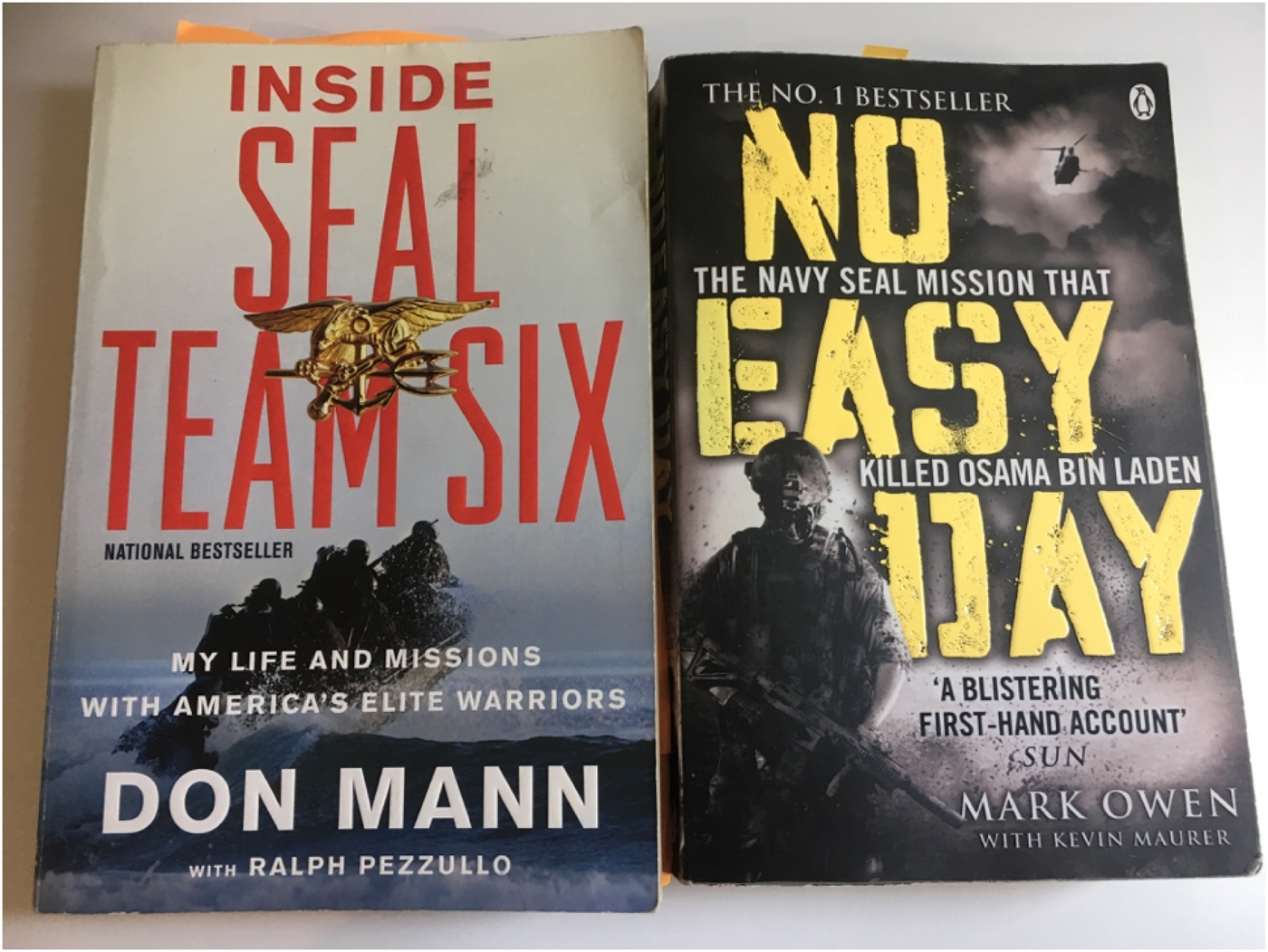

More specifically, using a discourse analytic approach, this article draws on a set of key memoirs of the US ‘shadow war’, some of which have generated significant controversy, in order to document the different secrecy practices and attendant subjects made public. Drawing on these texts written and co-written – including through ‘ghostwriters’ and the censoring processes of the US Defense Office of Prepublication & Security Review, which vets, alters, and redacts individual manuscripts – by US special operators (and one drone operator who worked alongside them), with a particular focus on those written by US Navy SEALs, this article explores how those at the ‘front lines’ of manhunting make sense of the secrecy practices they used and how these construct the subjects within this discourse (see Table 1). Many of these memoirs have made bestseller lists (Lone Survivor; No Easy Day; American Sniper; My Share of the Task; Drone Warrior), some have been made into popular Hollywood films, even garnering Academy Awards (American Sniper, dir. Clint Eastwood), and none of them can be completely trusted.Footnote 21 As Rachel Woodward and Neil Jenkings argue, military memoirs are ‘public narratives of war’ that are important sites of security meaning making.Footnote 22 They help generate the commonsense of war. These texts are then supplemented by analysis of investigative reporting on the shadow war and situated alongside existing academic scholarship on contemporary counterterrorism practices.

Table 1. Memoirs.

Secrecy is powerful and productive. As Michel Foucault suggests, ‘There is not one but many silences, and they are an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourse.’Footnote 23 To understand the power invested in security discourses therefore means paying closer attention to these diverse ways of secrecy and associated subjects function as legitimising forces.

Layer 1: Geographies of secrecy and ‘insider’ subjects

Two months before Operation Neptune Spear became public knowledge, 23 SEAL Team Six operators (ST6)Footnote 24 were recalled to their (unmarked) headquarters at the Dam Neck Annex, Oceana Naval Air Station, Virginia Beach under mysterious circumstances: ‘Something big was up and whatever it was, our leadership wanted it on a need-to-know basis’ (RO: 274).Footnote 25 Directed to the Commander's Conference Room in an area designated as a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, or SCIF (pronounced ‘skiff’), the operators were ‘read into’ a new mission, though only partly (MO1: 161). For in addition to being briefed in a space intentionally constructed as highly secret and ‘spy proof’ – with lead-lined walls to keep out electronic listening devices, encrypted data networks, special access passes, and a no outside phones policy (the White House Situation Room(s) being the most famous SCIF) – the select groups of US operators encountered the most intense regime of secrecy they had ever encountered before. For them, the secrecy surrounding the operation was ‘strange’, ‘brand-new, and very odd. Nobody knew what the hell was happening’ (RO: 272). Their leadership would not provide additional information and the operators were under an unprecedented level of direction not to speak about their mission to anyone outside their smaller group or in any detail beyond the walls of their briefing spaces. As Robert O'Neill recalled, ‘Even the other team leaders, Troop Chiefs, and troop commanders who hadn't been specifically recalled were asked to leave [the briefing room]. They had to be told a few times because they couldn't believe their ears’ (RO: 274–6).

After a cryptic initial planning meeting at their Headquarters, the operators were ordered to report the following week to an even more secret facility, ‘one of the most top secret defense facilities in the country’ (RO: 281), or as an anonymous contributor to the online crowdsourced open intelligence website Cryptome later identified, to the Department of Defense's Harvey Point Defense Testing Facility in North Carolina, a facility used by the CIA and FBI for counterterrorism training, including and especially for covert high explosives work.Footnote 26 Entering this facility meant passing through another round of secrecy measures, that, as operator Mark Bissonnette described, made sure the facility ‘[f]rom the outside … looked innocent’ (MO1: 170, meaning it hid no ‘guilty’ secrets). Harvey Point was shielded from the public road by a pine forest as well as by ‘the screens [that] hung down along the fence to block anyone from looking inside’ (MO1:170), a security guard-monitored the gate, an access list and facility-specific security pass system was used, a second ‘large ten-foot-tall wooden security barrier’ surrounded an inner perimeter ‘making it impossible to see inside’ (MO1: 170), and within the specific compound, additional security guards were also on hand. These security guards, however, had to be moved out of earshot when the briefing commenced, while a visual check was conducted ‘around the room to ensure that no one was in the room who didn't belong’ (RO: 282).

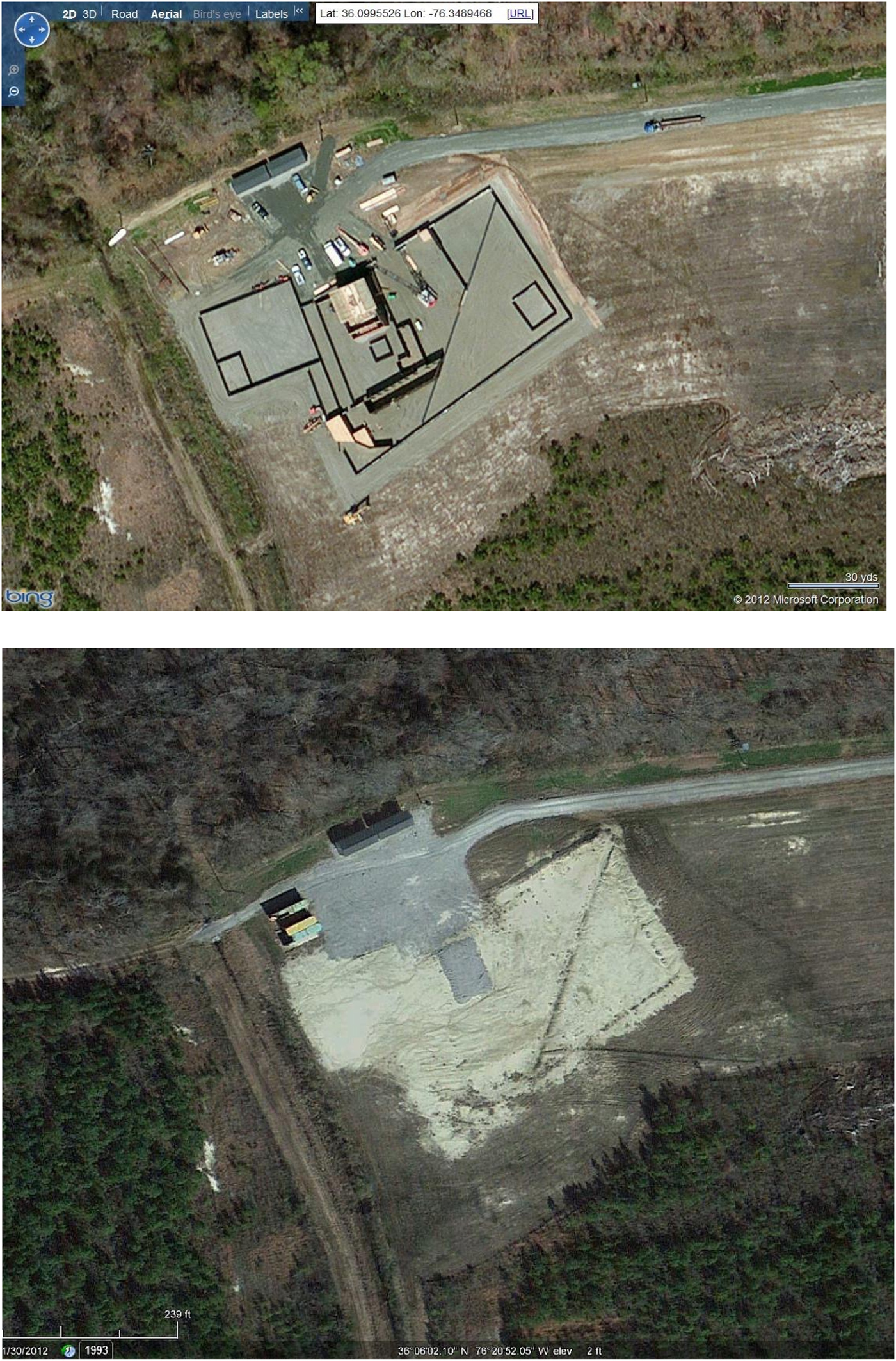

In other words, for the planning and training associated with Operation Neptune Spear to occur – the operation that would eventually be known worldwide as the mission that killed Osama bin Laden – succession of geospatial secrecy practices (an architectonics of secrecy) were mobilised to limit the spread of information. These practices for producing and monitoring spatial arrangements included: establishing physical boundaries (walls and fences, rooms and buffer spaces), as well as distant locations and relocations, which were in turn policed (key cards, access lists, visual checks) to control access, visibility, and sound transmission. Sitting alongside those were a second set of secrecy practices that can equally be understood as geospatial: controlling the flow of documents, including video and audio transmissions, through, for example, the elaborate processes of document security classifications and redactions to isolate and contain the flow of information, or in Trevor Paglen's words, to create ‘blank spaces on the map’ and prevent evidence of its existence from entering the public sphere (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 27 Collectively, these practices point to the ongoing importance of geospatial practices to secrecy; the making and unmaking of boundaries and associated geospatial practices (see Table 2), including the design of multiple and interlocking concentric boundaries, as the memoirs demonstrate, remains a core layer of secrecy within security discourses.Footnote 28 Within this set of practices, secrets are material objects with spatial qualities that can be contained, enclosed, and compartmentalised as space is delineated through ‘a set of structures such as fences, buildings, or fixed marks on a map’ to keep ‘dangerous knowledge’ contained.Footnote 29 The spatial and material practices paradoxically therefore take the form of new facilities and bureaucracies to manage the geospatial dimensions, the ‘traces’, ‘leaks’ in the containment, and outlines of which can be followed, even if the secret cannot.Footnote 30 For example, the visual traces detected by satellite of the mock-up of the Abbottabad compound at Harvey Point, along with evidence of its subsequent demolition.

Figure 1.1. Harvey Point Defense Testing with the bin Laden house life-sized replica, during preparations for the raid (Microsoft image), and after (Google Maps) as documented in Cryptome (Anonymous (2012)). Google Maps removed its publicly available satellite images of Point Harvey between 17 March 2010 and 30 January 2012.

Table 2. Layer 1: The geospatial compositions of secrecy or secrecy's architectonics.

Moreover, within this understanding, secrecy and secrets are spatially organised and owned as property. To have access to a secret space and its traces is to overcome the barriers of secrecy and therefore to have ownership, and power, over the secrets contained within. Correspondingly, for Paglen there is therefore ‘a strong connection between geography, secrecy, and extralegal violence’;Footnote 31 to hold or generate secrets is an act of power that ‘removes knowledge’, creates absences or blank spots, is anti-epistemological and is therefore an act of violence.Footnote 32

Within these memoirs, these geospatial secrecy practices were not only central to keeping the secrecy of Neptune Spear, but also worked to constitute the first secrecy subject: the ‘insider subject’ who can access spaces, move across barriers and into enclosures in order to know ‘secret’ information. For many of the operators, these were groups they wanted to join: ‘As soon as I heard that there was a special group … I knew I wanted to be part of the team’ (DM: 104) or ‘join the club’ (RO: 176). This ‘special group’ is then closely tied to the separate world they occupy and for being ‘in the know’, articulations common among clandestine and selective groups.Footnote 33 For Mark Bissonnette (AKA Mark Owens), operators existed in a ‘circle of trust’ (MO1: 204). For Brett Velicovich, who worked alongside special operators in targeting, their secret world was an ‘inner circle’ (BV: 69), ‘another world’ (BV: 79) or ‘a whole different world, sealed off’ (BV: 67). Physically, these secret spaces and compartments manifested in the form of their team rooms, referred to as ‘getting to the second deck’ (floor) of their headquarters: ‘a place historically reserved for warriors’ with an entrance ‘lined by Lost Heroes’ (BW: MO2), or for Velicovich, gaining special access to the unmarked trailers called ‘the Box’ that he and others were permitted to enter and work from when ‘hunting’ for terrorists. When access was denied, as in the case of Neptune Spear, the exclusion was distressing: ‘Every man in the room knew that this [extra layer of secret keeping associated with the operation] would cause a problem. The other guys would be wondering why they were not read-in and would think we were arrogant for not telling them what was going on’ (RO: 274–6). This included the policing of the insider subject and its geographies in relation to sexualities.Footnote 34 When Brett Jones, a Navy SEAL who had served ten years, was outed as gay in 2002 in the era of Don't Ask, Don't Tell, ‘all his clearances were pulled’. ‘I had to be escorted everywhere I went in my SEAL team building. I even got issues a new ID card with “Escort Required” printed on it in bold red letters’ (BJ: 137).

Approaching secrecy as geospatial therefore enables a richer understanding of the power of secrecy. However, while this is the dominant way through which secrecy is often culturally reproduced and understood in US security discourses, as evidenced, for example, through these memoirs, this perspective, as Perkins and Dodge argue, ‘reinforce[s] the view of secrecy as the dark opposite of publicity’ and spatially organised along a single axis of in/out, covered/uncovered, enclosed/exposed, silent/spoken, visible/invisible. Limiting the analysis to these geospatial practices of inside/outside, what Oliver Kearns calls ‘secrecy as enclosure’,Footnote 35 however, has two effects. First, it overlooks an additional set of geospatial practices that these memoirs illustrate: how geospatial practices of secrecy also entail the large and small scale, circulations and removals, and the complex, as discussed below. Second, it reproduces the sense that granting access to spaces, or documents, can reveal a secret. As Perkins and Dodge suggest, and as detailed across the following layers, accessing these spaces can ‘only hint at the nature of power, they cannot actually show us power relationships’ or the complexity of the ‘social practices that are performed in particular places’.Footnote 36 For this, more layers and subjects are needed.

Layer 2: Crafting secrecy and ‘stealthy’ subjects

Beyond the geospatial practices of secrecy, secret keeping within security discourses is often understood as reliant on technologies and techniques for composing secrets. Or, what is often referred to as using ‘the tools of the trade’ but might better be understood as the art and science of crafting secrets (as in ‘spycraft’ or ‘tradecraft’). In other words, secrecy as enclosure and containment may be a central way in which secrecy is understood and practiced, but it is closely followed by the conception of secrecy as a form of expertise and practice of secrecy craft.

As documented across the memoirs analysed, crafting secrecy is a core feature of the work of special operators.Footnote 37 These practices allow operators to move quietly, through the dark, or take action from longer ranges, and ultimately to detect, surveil, surprise, capture, kill, or rescue their targets. This includes using the ‘noble art of camouflage’ (ML: 156; BW); night-vision goggles; high-powered rifle scopes and muzzle suppressors to muffle sound; camouflaged cameras with long-distance lenses; covert audio recording systems; encrypted satellite-supported video, communication and navigation systems, including using drone feeds from larger drones, but also from smaller, shorter range ones; laser-guided targeting systems (the ‘light of god’) and infrared markers invisible to the ‘naked eye’; the ‘flash-bang’ stun grenades that overwhelm the senses; stealth helicopters for inserting special operators, such as the MH-6 ‘Little Birds’, MH-47 Chinooks, and H-60 Black Hawk helicopters designed with ‘radar absorbent material’ used by special operators (all flown by the 160th Special Air Operations Regiment (SOAR) (or Night Stalkers) who specialise in covert flying techniques); high altitude parachuting (high and low opening); and for SEALs in particular, the underwater diving equipment and the ‘swimmer delivery vehicle’ (SDV): ‘the minisubmarine that brings [SEALs] into [their] ops area … the stealthiest vehicle in the world’ (ML: 173). Many of these technologies and techniques are themselves often wrapped in layers of secrecy, as documented by Paglen,Footnote 38 including the nature of the modified Black Hawk helicopter used in Neptune Sphere.

The specially selected and trained bodies of special operators, however, and their mastery of the craft of secrecy, are an essential component of this layer of the composition (see Table 3). Or, as US Navy SEAL Petty Officer Marcus Luttrell, a SEAL sniper and the ‘lone survivor’ (made famous through his memoir and later the Hollywood film) claims, ‘it follows that the troops manning the world's stealthiest vehicle[s] are the world's sneakiest guys’ (ML: 173). In particular, their expertise revolves around two skill sets: the ability to navigate through unknown/secret spaces, whether urban, ship-based, or forest and jungle environments, for ‘snatch and grabs’ (HW: 52) and hostage rescue, and the stealthy movement and camouflaging skills associated with trained snipers. In the first subset of skills, operators are trained in ‘shoot houses’ (also known as ‘skills houses’ and ‘kill houses’) to navigate through spaces that may contain hidden threats and blind spots, mastering the art of movement through these unknown and often ‘maze-like’ spaces and detect the ‘traces’ of others (see Figure 2.1). For example, a core component of the preparation for Neptune Spear included top secret US government efforts to build and then use multiple versions of the Abbottabad compound in order to prepare the SEAL operators (and reassure higher ups), including a table-top version, and at least two life-sized versions, one being the Harvey Point construction (see Figure 2.2 and Layer 1).

Table 3. Layer 2: The technical and technological compositions of secrecy or secrecy's choreography.

Figure 2.1. Learning the choreography of training in a shoot house.

Figure 2.2. The National Geospatial Agency's scale model of Osama bin Laden's compound used to brief and plan Operation Neptune Sphere. See {https://www.stripes.com/news/middle-east/bin-laden-s-pakistan-hideout-turn-it-into-playground-or-graveyard-1.422184}.

Figure 2.3. US Army Special Forces Operational Detachment (Delta) operators in Afghanistan, searching for bin Laden.

Figure 2.4. The insignia of ST6 Red Squadron.

In the second subset, operators learn to move slowly and quietly, construct ‘hides’ (as animal hunters might) and camouflage themselves and their equipment (including learning to wear local clothing in order to ‘blend in’), to use longer range small arms, learning how to be where the enemy least expects as part of keeping the advantage of secrecy and surprise, and above all be patient. As SEALs say, ‘Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast’ (RO; HW). For Brandon Webb, the skillset of snipers is the pinnacle of the mastery of secrecy as craft, possessing ‘a set of capabilities that is as close to omniscience and omnipotence as a human being can get’ (BW: 20). In addition, all operators are trained in ‘sound’ and ‘light discipline’ (to monitor their emissions), to use coded language along with knowing how to use encryption software/systems and respect classification orders (of the sorts associated with Layer 1), and to survive, evade, resist, and escape (SERE) capture (CK: 49) so that all this craft become second nature or ‘muscle memory’ (HW: 87).Footnote 39

In the context of security discourses such as the GWoT, however, these skills in particular are part of the construction of masculinities tied to heroism, elitism, mastery, freedom, autonomy, and modernity. Or in other words, stealth and secrecy on the battlefield become synonymous with professionalism, warrior status, especially as ‘shadow warriors’,Footnote 40 ‘unconventional warriors’ (HW: 51) and even as ‘supersoldiers’. For intelligence analysts such as Brett Velicovich, the self-styled ‘drone warrior’, working closely with special operators in Iraq meant working with ‘the world's best professionals, giving them the tools and technology they never had access to before, and then seeing them free to do what they do best’ (BV: 66). For Luttrell, ‘This kind of close-quarter recon is the most dangerous job of all’ (ML: 25), SEALs therefore move ‘quietly, stealthily through the shadows, using the dead space, the areas into which your enemy cannot see. Someone described us as the shadow warriors. He was right. That's what we are’ (ML: 31). ‘[We're] big, fast, highly trained guys, armed to the teeth, expert in unarmed combat, so stealthy no one ever hears us coming’ (ML: 9). For O'Neill, the skills and professionalism of ST6 made them ‘wanted for the most sensitive, secretive missions with the most at stake’ (RO: 119). And for Howard Wasdin, as a ‘master of cover and concealment’, ‘when the US Navy sends their elite, they send the SEALs. When the SEALs send their elite, they send SEAL Team Six’ (HW: 3).

As such, discourses of crafting secrecy mobilise and intensify existing understandings of militarised hegemonic masculinity as tied to ‘courage, inner direction, certain forms of aggression, autonomy, mastery, technological skill, group solidarity, adventure and considerable amounts of toughness in mind and body’.Footnote 41 Within these memoirs, SEALs are often described as ‘elite warriors’ alongside constructions of masculinity: they are ‘all that is best in the American male – courage, patriotism, strength, determination, refusal to accept defeat, brains, expertise in all that they did’ (ML: 53). On top of this, and intensifying this construction, is layered the additional element of secrecy: Or, as journalist Mark Bowden explains, ‘In the [US] military, secrecy is status … It's an awfully powerful cultural pull.’Footnote 42 Sniper training, for example, includes ‘the ultimate examination of a man's ability to move stealthily, unseen, undetected, across rough, enemy-held ground where the slightest mistake might mean instant death, or, worse, letting your team down’ (ML: 156). The mastery of the craft of secrecy, including its technologies, produces these hegemonic masculine figures who seemingly become all knowing and all powerful by their capacity to be secretive and to detect secrets, and are heroic, even superheroic, for doing so.Footnote 43

Therefore, in addition to producing secrecy through managing the geospatial, operators are trained to mask, silence, and invisibilise themselves while detecting the ‘traces’ of others; to manage and even ‘master’ the sensory-world, what might be understood as a choreography of secrecy. This layer of secrecy therefore begins the process of recognising that occupying a space, or being an ‘insider subject’, is not sufficient for understanding the power of secrecy. Knowing a secret is more than breaking its containment, it requires an expertise or craft in order to interpret or recognise its presence. Consequently, expert practices of secrecy are deeply intertwined with the construction of a second subjectivity, that of ‘stealthy’ subjects. Stealthy subjects not only have access to secret knowledge but are experts, even ‘masters’, in managing the ‘sensory milieu’Footnote 44 in a particular way – whether covertly (unseen and unheard, for example in the cover of night) or ‘hidden in plain sight’ (walking in disguise among a crowd) (Figure 2.3).Footnote 45 ‘Stealthy’ subjects are also constructed by virtue of their ability to present and embody two or more identities and to move between spaces safely and undetected by virtue of this craft. Therefore, unlike ‘insider’ subjects who rely on geospatial containment practices to construct identities, for legitimacy, and for their claim to access and produce security knowledge (for example about targets), it is the ability of stealthy subjects to shift between identities across space and within them, and to master the sensory milieu, that constitutes their legitimacy and the legitimacy of their actions.

Moreover, while insider subjects construct the world as made of clear inside/outside distinctions, and in particular keeping curious outsiders away from secrets, stealthy subjects begin to trouble this sharp distinction, taking advantage of the lack of curiosity or attention of others and relying on knowledge of conventions, categories, and stereotypes in order to move unobserved. Stealthy subjects and practices therefore must be understood not only as a strategy of resistant or marginalised communities, as ‘passing’ subjects might be,Footnote 46 but as part of the crafting practices of dominant and hegemonic powers.Footnote 47

Finally, interconnecting with the gendered constructions of military masculinity inherent in special operators’ constructions of themselves as ‘stealthy’ subjects, are their constructions of stealth in a particularly racialised way. As Patricia Owens argues, ‘military orientalism’ is ‘made possible by other discourses, those of sexuality, gender and race’.Footnote 48 While there is an implicit construction of elite warriors and ‘whiteness’ against the racialised terrorist other who is ‘sneaky’ (‘as rats’, for example) as true ‘modern’ men,Footnote 49 often tied to class-based constructions (against ‘rednecks’ but also against ‘suits’ or DC-based elites), but most particularly tied to ‘hunting’ discourses in US American culture that remain and centre whiteness,Footnote 50 these crafting secrecy practices constitute special operators as supersoldiers and warriors first as ‘ninjas’ and more recently as Native American ‘braves’ despite the ongoing lack of diversity within special operator communities.Footnote 51 Most notably, while ST6 is made of six squadrons, where the ‘Gold Squadron’ occasionally features the ‘crusaders cross’ for example, the ‘Red Squadron’ takes as its central identity that of a ‘Tribe’ (see Figure 2.4): the logo, featured on flags, shoulder patches and tattoos, even on the 15 × 10 foot black-and-white carpet that decorates their Team Room, centres around a stylised image of a Native American ‘chief’. Moreover, a life-sized statue of the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh (with no sense of irony)Footnote 52 adorns the entryway to ST6 (RO: 273), while each ST6 member was given a ‘tomahawk’ weapon to carry into battle.Footnote 53 Most importantly, it is the construction of the secretive fighting skills, especially as a master of the stealthy ‘hunt’, that are made central to this cultural appropriation: Operators simultaneously describe their work as going into ‘Indian country’ and fighting the ‘savages’ while also taking pride in their ability to move as silently and as stealthily as to ‘make an Apache scout gasp’ (ML: 156). As Howard Wasdin describes: ‘we embraced the bravery and fighting skills of the Indians’ (HW: 151). O'Neill, deployed to Ramadi in Iraq as part of ST6, describes in particular how they ‘honed [their] tactics and techniques’ in stealth (RO: 191):

[w]e became so good at entering targets silently that we started playing a game we called ‘counting coup’ in honor of Native American warriors of the past. … To demonstrate their courage and stealth, Native Americans would creep up on their sleeping enemy and touch him, even take items off his person without waking him. So we started doing that too. We'd sneak up on a house full of bad guys and enter as quietly as we could, forgoing explosives for the silent removal of windows, picking locks, or whatever clever ways we could think of that would make minimal noise (RO: 191–2).

Overall, special operators therefore rely on and reproduce a second set of practices, the techniques and technologies of secrecy that are part of the crafting, or even the choreographies of secrecy. Mastery of the multisensory domain, both to conceal their own traces and to reveal those of others, is integral to constituting themselves as professional, heroic, and elite ‘warriors’, but this discourse reproduces racial and gendered security discourses. The result is therefore the reproduction of a second layer of subjectivity, that of ‘stealthy’ subjects that are gendered and raced in particular ways.

Layer 3: Disciplining secrecy and ‘quiet’ subjects

On 31 October 2014, Rear Admiral Brian Losey, the Commanding Officer of Naval Special Warfare Command (the SEALs), and the senior enlisted SEAL, Force Master Chief Michael Magaraci, circulated a letter to all within the Command:

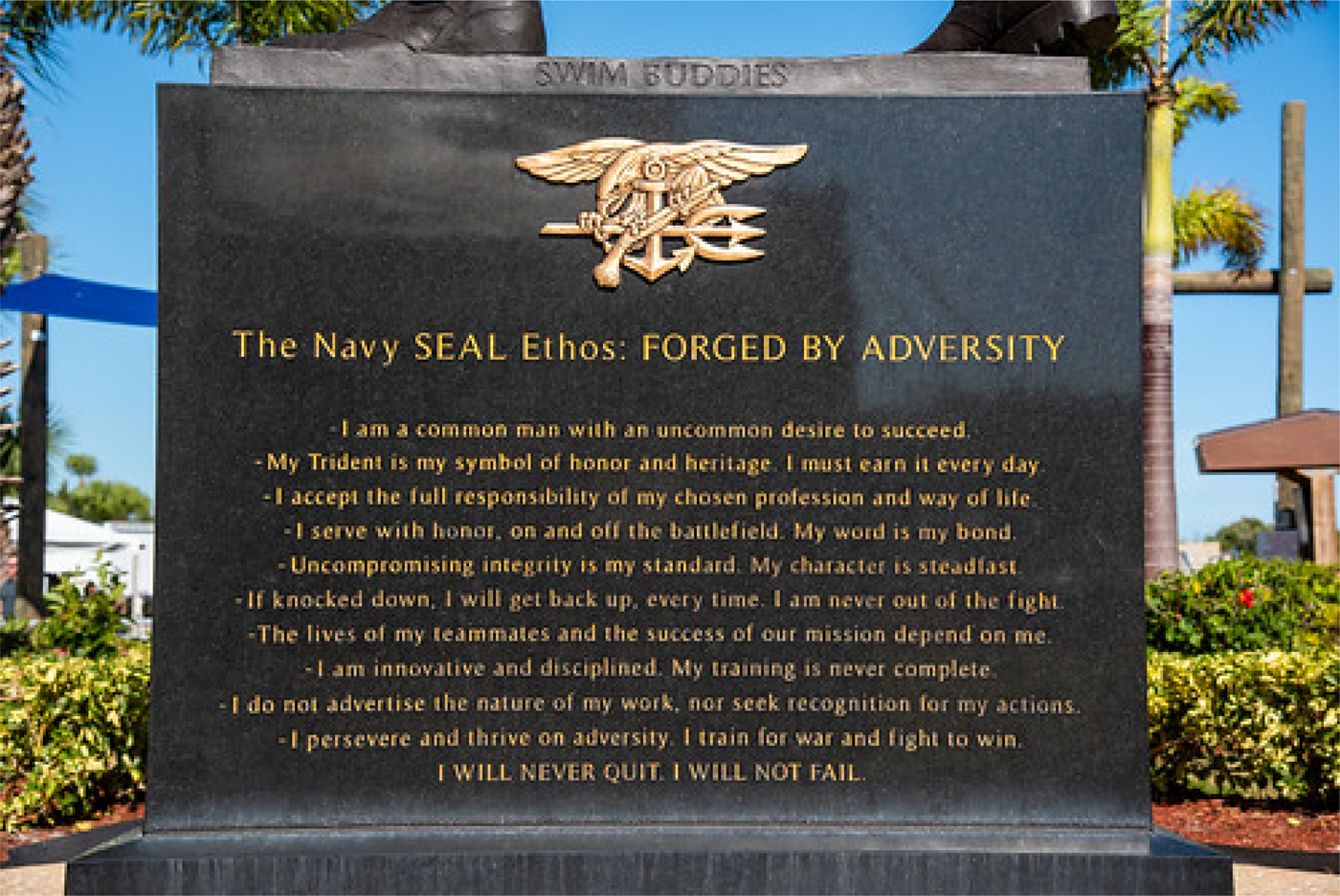

Figure 3.1. The Navy SEAL Ethos: ‘I do not advertise the nature of my work’, outside the Navy SEAL Museum.

Each day, thousands of current and former members of Naval Special Warfare live as ‘quiet professionals’. Our members continue to serve around the world, accomplishing critical and sensitive missions that contribute to our national security, and keep our nation safe … undertaken with little individual public credit. It is the nature of our profession.

At Naval Special Warfare's core is the SEAL Ethos. A critical tenant of our Ethos is ‘I do not advertise the nature of my work, or seek recognition for my actions.’ Our Ethos is a life-long commitment and obligation, both in and out of the Service. Violators of our Ethos are neither Teammates in good standing, nor Teammates who represent Naval Special Warfare. We do not abide willful or selfish disregard for our core values in return for public notoriety and financial gain, which only diminishes otherwise honorable service, courage and sacrifice. Our credibility as a premier fighting force is forged in this sacrifice and has been accomplished with honor, as well as humility.Footnote 54

What part prompted this letter were the ‘revelations’ by two Navy SEALs, and importantly two ST6 operators, of first-hand accounts of Operation Neptune Spear. Historically, SEALs are understood to have a ‘carefully cultivated aura of secrecy’, and pride ‘ourselves for being the quiet professionals’ (MO1: 333; SM: 112), for being ‘part of a team with a code of silence’ (RO: 322). These ‘quiet professional’ are made material in the signs that decorate US special operator spaces, for example within the spaces of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), ‘The Deed is All, Not The Glory’ that discourages seeking fame, fortune, and ‘Ego’; the codified SEAL Ethos that forms part of their training (see Figure 3.1); and reinforced through the non-disclosure agreements that they are obliged to sign when they join and when they leave (as well as the NDA signed in connection with Neptune Spear).Footnote 55

Following Neptune Spear, however, Bissonnette and O'Neill (AKA ‘The Shooter’) nevertheless violated these non-disclosure agreements and, even worse to many SEALs, the SEAL Ethos, in ‘going public’ about the raid: Bissonnette through a pseudonymously published and unauthorised hit memoir, No Easy Day (MO1), which was not cleared by US military censors, accompanied by an interview on CBS's 60 Minutes; and O'Neill through an anonymous interview in Esquire where he identified himself as the one who fired the shots that ultimately killed bin Laden, an appearance on Fox News to pre-empt the revelation of his identity, and later, his own memoir, The Operator (RO), with a new career as a motivational speaker.Footnote 56

Bissonnette and O'Neill have therefore become the highest profile focal points of a recent concern within special operations communities that this longstanding, and for some, fundamental, code of silence of the ‘quiet professionals’ has been broken.Footnote 57 For those concerned, operators going public so soon after retiring offers a significant challenge to this code, to the secrets it is meant to safeguard, and therefore to a set of interconnected securities: US national security (and by extension through the GWoT discourse, international security), operational security (OPSEC) and security of US soldiers operating abroad, a threat to ST6 community cohesion and therefore effectiveness, to the personal safety and security of SEALs when home, the security of their families and wider communities, as well as a threat to the mythos itself. President Obama, for example, singled out the ‘quiet professionals’ who took part in the raid and whose success ‘demands secrecy’, doing so again and again in speeches that celebrated ‘the consummate quiet professional’, one of a ‘special breed of warrior that so often serves in the shadows’.Footnote 58 For Obama,

The American people may not always see them. We may not always hear of their success. But they are there in the thick of the fight, in the dark of night, achieving their mission. … We sleep more peacefully in our beds tonight because patriots like these stand ready to answer our nation's call and protect our way of life – now and forever.Footnote 59

For many, including the operators themselves, their leaders, those who work alongside them, live with them, and for many who report on their operations, the success of their missions ‘demands secrecy, and that secrecy saves lives’.Footnote 60 For Rear Admiral Sean Pybus, head of Naval Special Warfare Command (2011–13), ‘“hawking details about a mission” and selling other information about SEAL training and operations puts the force and their families at risk’.Footnote 61 Or as Navy SEAL Lieutenant Forrest Crowell argued:

The raising of Navy SEALs to celebrity status through media exploitation and publicity stunts has corrupted the culture of the SEAL community by incentivizing narcissistic and profit-oriented behavior … [It] erodes military effectiveness, damages national security, and undermines healthy civil-military relations.Footnote 62

In short, special operators are constructed as ‘quiet’ subjects, including through the reaction to these ‘transgressive’ acts, such that their actions are not only intentionally kept secret through the practices of Layers 1 and 2, but through an associated set of disciplinary processes that help interpolate subjects into keeping these secrets as well (see Table 4).

Table 4. Layer 3: The cultural compositions of secrecy or secrecy's discipline.

As Joseph Masco has argued with relation to nuclear secrecy, intensified secrecy regulations or ‘hypersecurity protocols’ reveal ‘that the most portable nuclear secrets are not in the documents but are locked up in the experience and knowledge of weapons scientists’.Footnote 63 For secrets to remain secret, one or two layers are not sufficient, a multilayered composition is needed that specifically enrolls the subject (including and widening out to their families and their communities) into keeping secrets beyond the practices already discussed. In other words, this means to live as a ‘quiet professional’ when encountering the public (or as a Goffman-esque interpretation might suggest; to live the ‘dramaturgy’ of a quiet professional in the front stage) while performing as a ‘stealthy’ and ‘insider’ subject with colleagues (in the backstage).Footnote 64 These public-facing practices therefore include encouraging members to stay silent and go unnoticed (‘dressed like civilians, and tried to look like civilians’ (DM: 160)) or to lie and use a cover story (to create secrecy fictions). Covers, for example, have included being part of a skydiving team, working for the embassy, or working for a relief organisation (RO: 128; ML: 283; HW: 10, 151; DM: 154).Footnote 65 Only after some time has passed – the informal rule that Bissonnette and O'Neill violated by ‘going public’ so soon after retiring (along with taking personal credit) – are ‘quiet professionals’ permitted to speak more openly, even to write memoirs.

Adding this layer of the composition therefore helps to move the discussion of the power of secrecy away from the geospatial and (often ‘high’) technological crafting of secrecy, to a greater focus on the interconnections between the subjects, their bodies, their cultural surroundings, and ‘low’ technologies needed to keep a secret. For example, wearing their hair longer than permitted by US military regulations to blend in. It also troubles the focus on ‘intention’ at the centre of many definitions of secrecy.Footnote 66 This third layer, that mobilises the less spoken about cultural and intimate practices associated with secret keeping within security discourses, requires the existence of a cultural context into which operators can ‘disappear’.Footnote 67 For the ‘quiet professionals’, being stealthy also involves ‘hiding in plain sight’ and ‘covering’, often within their own communities and through the support of their communities, by adopting the signs, cultural codes and conventions of the given identity into which one moves and steering away the curiosity of others, as they are taught (BV: 79; MO2: 6).Footnote 68 In other words, being quiet always also entails a raced and gendered component.

Quiet subjects also require a public that is much less curious about the ‘secret’ than is commonly assumed. As Thomas Kirsch argues, part of the power of secrecy is connected to the reproduction of the cultural construction of the ‘epistemophilic other’, an active subject that is always seeking out secrets.Footnote 69 In practice, part of the ability for ‘quiet professionals’ to cover over their secrecy and to ‘hide in plain sight’ are the routine and everyday ways in which they come in to contact with an epistemophobic other, such that they are ignored, left alone or unchallenged – whether eating out with family members, or driving along public roads – by communities which have the ‘privilege of unknowing’Footnote 70 and don't feel threatened or feel compelled to ask questions. As operators recognise:

Most of my neighbours were oblivious to what I or any of the guys who came to my house did when they were at work (MO2: 6).

What would the people in all the cars passing by say if they knew what the big bearded guys in that van beside them might be on their way to do? (RO: 281).

But this code of silence is also a deeply masculine one, as codes of silence (or omertà) often are. ‘Snitches’ and ‘leakers’ are derided for their inability to contain themselves, as feminised ‘gossips’ who have ‘gone wild’Footnote 71 put themselves ahead of their (male) honour and the honour of their community.Footnote 72 Despite the prevalent flow of gossip and ‘rumint’ (rumour ‘intelligence’) (MO2: 3) within these communities, on the ‘frontstage’ it is heroic to stay silent, to be ‘discreet’Footnote 73 as Lilith Mahmud might argue, to ‘hold demons inside’ (BV: 192), or ‘live the lie’ (RO: 103). For Velicovich, this heroic silence was a cost to be borne in the service of US security:

You had to bottle war up, even when your instinct was to talk and sort things out. Any accomplishments could only be shared among the group. … I had learned to give up the idea that I should be patted on the back or hugged every time I did good … None of that mattered. I had an important job to do and American lives depended on me to do it well, whether they knew about our existence or not (BV: 77).

I couldn't talk to anyone at home about anything. Everything I did was top secret. … Normal sentences became censored, my mind reciting the lines in my head multiple times before they were spoken aloud. It forced me to become quieter and more introverted. I simply shut down when I wasn't in the office (BV: 150).

Moreover, ‘quiet’ subjects are reproduced within these memoirs through their commitment to their teammates, their ‘brothers’, ‘family’ (BJ: 124), for example the SEAL ‘Brotherhood’ (KB: 3; CK: vii; BJ: 124; MO1: v; MO2: 17). Quietness is therefore also tied to a notion of a cis-gendered loyalty and honour to the homosocial spaces that are the ‘teams’ and ‘brotherhoods’ where, as Sharon Bird argued, normative heterosexual hegemonic masculinity can be reproduced – whether in the exclusive spaces that are the Team Rooms (Layer 1), in the private spaces of their homes, or in the public spaces where they also often socialise, including and often in the strip clubs discussed in the memoirs (RO; HW; CK; BJ; MO2; DM).Footnote 74

This layer of secrecy therefore emphasises an additional component. Within SOF communities, violators of the code of the quiet professional are noticed and punished, as much if not more than those who fail in their duties in relation to Layers 1 or 2. As a small community of ‘brothers’ who ‘work hard’ and ‘play hard’ together, ‘each SEAL is constantly being judged by the team’ (BJ: 124; MO1: 35).

Everything from one's physical condition, to marksmanship, to communication, to one's form when diving … SEALS who do just enough to get by find themselves at the top of the gossip [rumint] network. Once someone is labelled a ‘shitbag’, it is a tough road back to redemption (BJ: 124).

O'Neill experienced this policing when he was ordered not to share the secret of Neptune Spear within the community; keeping this secret was a (gendered) problem: ‘Every last one [of the other members of the squadron] was pointedly ignoring us, like a jealous girlfriend who didn't want to come out and say that she felt left out’ (RO: 274–6). Equally, Bissonnette, for example, has been subjected to a certain amount of blacklisting and is ‘persona non grata’ among the SEAL community in response to the ‘greatest betrayal[s] the community has ever known’.Footnote 75 ‘“There are people in the community who aren't talking to me anymore”, he said, especially active-duty SEALs who fear their careers would be ended if caught communicating with him.’Footnote 76 Bissonnette's former commanding is officer is reported to keep a mock tombstone with Bissonnette's name on it, along with O'Neill's, and instructed Bissonnette to delete his phone number.Footnote 77 ‘Those who divulge mission secrets to reporters – even retired SEALs who appear as analysts on television – are often criticized or even ostracized by peers.’Footnote 78 SEALs are socialised into ‘quiet’ subjects, either enrolling into this subjectivity and policing its boundaries, or face expulsion. In other words, to cover over the secret requires disciplinary power that functions on a very personal and everyday level for operators, and yet is a key part of the composition.

Layer 4: Magical secrecy and ‘alluring’ subjects

In the immediate aftermath of Operation Neptune Spear, friends, family and colleagues, former ST6 squadron commanders, and the Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta all sent private messages of congratulations to the operators involved. In some cases, meeting with them to shake their hands and offer their congratulations, as Vice President Joe Biden and President Barack Obama did. When the news broke, the US media and members of the public also wanted their chance to get a little closer. For example, descending on Virginia Beach, the ‘open secret’ home of ST6, in attempts to go ‘SEAL-spotting’.Footnote 79 Publishers, filmmakers and television producers, often assisted by the US military, moved quickly to respond and (re)produce this growing demand for special operative-related content. In other words, in recent years, in connection with the operation, but also spurred by greater media attention surrounding the near-capture of Luttrell in Afghanistan in 2007, and then the rescue of the hostage Captain Phillips in 2008 by SEALs, the reputation and public presence of SEALs and other special operators such as Delta or Army Rangers have grown. Over fifty memoirs and histories of SEALs alone have been published, many of which have made bestseller lists in the US or turned into Hollywood movies, including Lone Survivor; Act of Valour; and the Oscar-winners American Sniper and Zero Dark Thirty, while new US television shows appeared, including Stars and Stripes (a reality-television show that paired celebrities with special operatives, including Chris Kyle) and CBS's SEAL Team. Meanwhile, ‘sales of merchandise at the Navy UDT-SEAL Museum in Fort Pierce, Fla., are up 200 percent [and in] Chesapeake, Va., ex-SEAL Don Shipley has been flooded with calls and e-mails seeking information about his Extreme SEAL Experience camp’, and a growing number of retired SEALs have entered politics, staking out their claim to office on their military credentials, including Missouri Governor Eric Greitens (removed from office in 2018)Footnote 80 as well as former SEAL and Montana congressman Ryan Zinke as the Secretary of the Interior in the Trump administration. Following the raid, a ‘skyrocketing’ in the number of cases of ‘stolen valour’, or men falsely claiming to be SEALs, were reported.Footnote 81 While romance novels also featured a resurgent interest in SEALs and other special operatives as their male protagonists (see Figure 4.1).Footnote 82 SEALs are increasingly ‘alluring’.

Figure 4.1. Cover design, Navy SEAL Security by Carol Ericson; Still from Eric Greitens campaign advertisement ‘On Target’, 2016.

Figure 4.2. Sample DEVGRU Challenge Coins available to purchase.

Figure 4.3. Cover art for Inside SEAL Team 6 (DM) and No Easy Day (MO1).

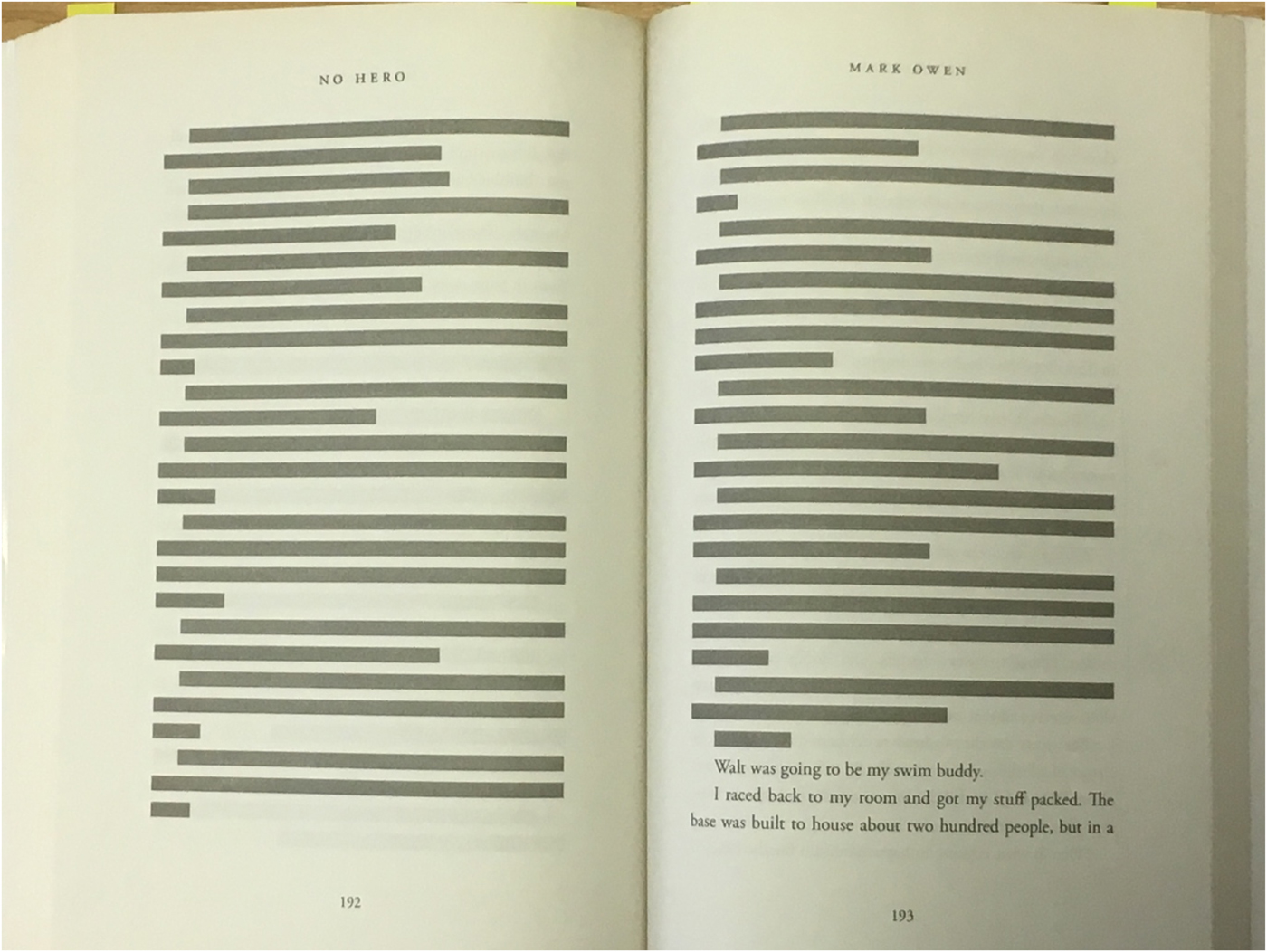

Figure 4.4. Extract from Mark Bissonnette's No Hero (MO1).

For some within the special operator community, this interest is understood as a desire to ‘touch the magic’. In other words, for all the talk of ‘quiet professionals’, special operators often understand themselves as ‘alluring’ subjects – many even confess in these memoirs to being recruited based on this allure, or that this ‘allure’ played a role in attracting sexual partners. Spying, after all, can be ‘sexy’ (BV: 43).Footnote 83 As Velicovich (BV: 158) and Bissonnette (MO1: 323) construct themselves, women and politicians seek out opportunities to ‘touch the magic’, to get closer to the world of covert operations. For example, as Velicovich describes:

The girls [women working at the US Defense Intelligence Agency] always seemed to perk up when we arrived … There was something that got these girls hooked when they worked with us or the SEALs. I think they got a taste of what it was like to get out from behind their desks – we called it ‘touching the magic’. The upside for us was that the girls from the DIA were always good looking (BV: 158).

For O'Neill, flying on a US military ‘Little Bird’ reaffirmed a connection between stealth, technology, and heterosexuality: ‘Every time I took off on one, I'd say to myself, Yep, chicks dig this’ (RO: 194, emphasis in original). Reproducing the US popular culture of ‘hard bodies’ tied to discourses of modern masculinity, SEALs construct themselves as alluring through their ‘perfect physique’ (RO: 102) – crafted as part of the second layer of secrecy – as often ‘damn good-looking’ (RO: 323), ‘studs’ (RO: 326), ‘cool guys’ (RO: 334), ‘buff guys, most of us good-looking’ (HW: 10), ‘ripped’ (CK: 42), with ‘strong features and a square jawline’ the ‘textbook image of a chiselled Navy SEAL’ (RO: 39) with nicknames like ‘Tripod’ or ‘Casanova’, or described as a ‘ladies’ man’ and the type who had ‘panties thrown at [them]’ (HW: 11).Footnote 84 They are ‘hardasses’, ‘assholes’, and ‘pricks’ (CK: 100), ‘hard’ and ‘tough’, and amazing physical specimens (DM: 78; CK: 216). They are in ‘impeccable physical condition’ or are a ‘physical phenomenon who emitted visible rays of intimidation’ (CK: 102). This physicality is then tied to their sexuality: For Kyle, SEALs spend their ‘downtime impressing women, living the SEAL dream’ (CK: 120) and ‘hitting up babes’.Footnote 85 Most importantly, what is reflected in these memoirs is therefore a culture of articulating not only physicality, expertise, and mastery (Layer 2), but also connecting this to (hetero)sexuality, pleasure and value, which includes watching and comparing each other's physiques, ‘bullying others when they are out of shape’ (CK: 214; HW: 91), and excluding the bodies of non-conforming non-heterosexual cis males (KB, BJ).

As a final layer of secrecy, secrecy therefore operates within security discourses to construct subjects, legitimate military intervention, and reproduce forms of ‘expert’ knowledge through the reproduction of this ‘allure’, this ‘covert spectacle’ (see Table 5).Footnote 86 Merging insight from recent scholarship on the pleasures of war as well as investigations into secrecy as cultures and affects, the power of secrecy can be understood as connected to the ‘adornment’ of secrecy (or secrecy as ‘ornamentation’), the careful interplay and co-constitution of secrecy as revelation, and the value, including economic value, that is often associated with this interplay.Footnote 87 Like a burlesque fan dance or a magic act that manufactures a scarcity of information for entertainment, the secrecy practices surrounding special operations also entail a selective and controlled revelation, a performance of secrecy that helps to justify their ongoing existence and their secrecy, building up and facilitating their credentials as secret keepers and therefore their power.Footnote 88 Secrecy therefore becomes, as George Simmel contended, an ‘adorning possession’.Footnote 89 Knowledge is once again property and contained (Layer 1) but it can also be understood as generating affects of secrecy which have value and circulate as part of the logic of these security discourses.

Table 5. Layer 4: The spectacle of secrecy or secrecy's performance.

In other words, ‘alluring’ subjects and magical or ‘revelatory’ secrecy practices trade, often literally, on the pleasures and feelings that come from the partial revelation of information. These practices are part of a broader set of cultural practices and processes that sees value in (partial) concealment, where to reveal all would be ‘obscene’ or ‘spoil it’.Footnote 90 Rather than understanding concealment as covering over that which is dangerous for the benefit of ‘insiders’ and ‘experts’ only (Layer 1, Layer 2), ‘alluring’ subjects protect the secret while also signalling its existence, encouraging others to take pleasure in secrecy as well and gaining financially or otherwise as a result.Footnote 91 In particular, revelatory secrecy practices articulate secrecy, cleanliness, and purity; secrecy supposedly covering over that which is pure and uncontaminated, saving secrets ‘from prying eyes’, ‘grubby fingers’, a ‘defilement’, or even a ‘desecration’.Footnote 92 Magical or revelatory secrecy practices therefore may even function, as Murray Leeder argues about magic, ‘as the secular re-enchantment of the world after the decline of religion’, in this case not only promoting science as magic, but also through promoting highly specialised and crafted military operations as ‘magical’.Footnote 93

To that effect, challenge coins, for example, illustrate these interconnections between secrecy, revelation, circulation, intimacy, and pleasure allowing those within (‘insiders’) or outside (‘outsiders’) special operation communities to ‘touch the magic’ (see Figure 4.2).Footnote 94 Often presented as a collector's item, challenge coins can be bought online, but those most highly valued, including those associated with ‘elite’ and top secret units such as ST6, are those carried by operators themselves to signal their inclusion – they are ‘ornaments’ of secrecy in Hugh Urban's sense and markers of belonging to the ‘brotherhood’ of ‘quiet professionals’ (Layers 1 and 3). These coins are, however, carried surreptitiously (in pockets, rather than worn like badges) and more importantly exchanged and circulated through ‘secret handshakes’, a literal ‘touching the magic’ and form of intimacy, when given as tokens by operators in return for a favour: ‘A SEAL challenge coin is especially valued, both for its rarity and symbolism. Slipping it [a coin] to someone in the navy is like giving him a secret handshake’ (CK: 224).

Most importantly, as a genre, and as part of the composition, memoirs themselves are explicitly revelatory practices in this dialectical sense, making them interesting objects in and of themselves to study secrecy practices and the constitution of the ‘alluring’ subject. In terms of revelation, these memoirs construct ‘alluring’ subjects in multiple ways. First, through their adherence to the traditional narrative arc of the genre, interweaving the high drama and transformative power of combat and training with ‘an intimate glimpse into the life and work of a SEAL’ (MO2: 17): O'Neill having dinner with his children before deploying, Kyle documenting his marriage alongside the descriptions of the challenges of training and operations.

Second, the memoirs also reproduce the sense of an ‘intimate public’Footnote 95 by claiming to reveal details of inner thoughts that even close family members are supposedly unaware of:

I couldn't say anything. I told them I was just passing through … A part of me thought they wouldn't really understand … I was working in another world. (BV: 79).

SEALs hadn't fired a shot in anger in years. But nobody ever admitted that around civilians, even to their closest non-SEAL friends. We'd pull the old ‘can't talk about it’ crap, leaving the impression of untold secret missions. We actually referred to the whole charade as ‘Living the Lie’ (RO: 103).

Therefore, as Molly Pulda argues, ‘For all that it confesses, memoir also elides, rendering unspeakable subjects sharable.’Footnote 96 Or as Catelijne Coopmans and Brian Rappert argue, memoirs of secrecy subjects are alluring by simultaneously presenting ‘evidence of their genuineness with evidence of their ability to mislead’.Footnote 97 The effect is a formula has been widely popular helping to generate the ‘intimate public’, construct the ‘public narratives of conflict’,Footnote 98 and reproduce the mythos of special operators and operations, while constructing what is considered transgressive or ‘dangerous knowledge’ and what is considered ‘ordinary’ within the security discourse. As much as these memoirs mobilise the promise of the genre to offer an ‘insider look’ and an ‘intimate glimpse’, a behind the scenes take, even a ‘tell all’ (see Figure 4.3), as Neil Jenkings and Rachel Woodward document in relation to UK military forces memoirs, they are also filled with (self-)censorship that is itself revealed, even highlighted.Footnote 99 For example, Velicovich draws attention to the secrets beyond what is revealed in his memoir:

the U.S. government won't let me say much about how I was recruited into the unit or the gauntlet of mental tests that only a few pass to gain entry into what is hands-down the most elite organization in the military. I can't tell you about where I went, the people there, or what went on … Most of what I wrote about the process in an earlier version of the book was completely redacted and blacked out. The government wants to keep it that way (BV: 60).

‘What was behind that black door? Unfortunately, the government won't let me tell you’ (BV: 63)

Finally, these memoirs also help to produce the ‘alluring’ subject through a set of interconnected visual practices that extend from the shadow figures that often populate the covers, the blacked out words, but also the blurred faces or concealed eyes of operators within photographic inserts (Figures 4.3 and 4.4).Footnote 100 Some memoirs, for example The Operator (RO), published in 2017, consistently redacts ‘Six’ in mentions of ST6, while others leave the Six uncovered. Some memoirs leave censored passages out. Others, such as No Hero (MO1) or Inside SEAL TEAM SIX (DM), include entirely redacted pages so that ‘readers will understand that [their] experience and knowledge go even further’ (DM: v). All of these practices, however, are practices that declaim, as an ‘insider’ subjects (Layer 1), ‘I know something you don't know’ (a ‘speech act’ that is nevertheless an intentional public performance of secrecy via invisibility or silence), but that also helps to constitute these subjects as ‘alluring’.

Overall, magical secrecy practices are also finally heavily dependent on the complicit spectator. Revelatory practices such as memoirs and collectible challenge coins would not be possible without the recirculation of these objects and their ideas by a ‘certain kind of (halfway) knowing spectator’.Footnote 101 Those who consume, and are happy to limit their curiosity to this consumption, are essential for the reproduction of this layer of secrecy.

Conclusion: Secrecy, the foreign ‘other’ and the ‘modern’ self

Secrecy as a legitimate practice of war is part of the construction of the ‘self’ as this article argues. It is also, however, a key element in the construction of dangerous ‘others’. Whether more historically, for example through the UK's ‘careless talk’ campaign of the Second World War, or during the Cold War where, as Jutta Weldes argues, ‘[t]he legitimation strategy pursued by U.S. decision makers was successful precisely because it drew on the already familiar representations provided by the U.S. security imaginary … the already established reputation, or better, representation, of totalitarian regimes as secretive and duplicitous.’ Footnote 102

More recently, within the context of the GWoT, dangerous secrecy was a key element justifying action. As key figures in the Bush administration articulated early on:

War has been waged against us by stealth and deceit and murder (Bush, 14 September 2001).

Thousands of dangerous killers, schooled in the methods of murder, often supported by outlaw regimes, are now spread throughout the world like ticking time bombs, set to go off without warning … A terrorist underworld – including groups like Hamas and Hezbollah … operates in remote jungles and deserts and hides in the centres of large cities (Bush, 29 January 2002).

[I]n order to fully defend Americans, we must defeat the evildoers where they hide (Bush, 11 October 2001).

This is, in some respects, as big as any war we've fought. And, at the same time, it is against an enemy that hides, an enemy that is in important ways invisible (Wolfowitz, 23 February 2002).

It is a global conflict against a hidden and deadly enemy with many faces in many places (Kerry, 3 December 2003).Footnote 103

Danger became synonymous with ‘terrorists’ who ‘have spent their lives eluding U.S. forces’ (BV: 85): hiding in ‘spider holes’, in plain sight among non-combatants, using the cover of darkness or a crowd, hiding in a ‘blind spot’, covering their tracks, hiding IEDs, wearing suicide vests, using ‘booby-trapped’ buildings, or women carrying concealed weapons.Footnote 104 Secrecy as dangerous, as Helen Kinsella argues, also coalesced in the sexed bodies of Afghanistan women.Footnote 105

Security discourses in short often rely on a construction of a dangerous and racialised ‘other’ that uses secrecy as part of this construction. These memoirs and the layered composition of secrecy therefore also tells a story about the mapping out and reproduction of the ‘legitimacy of social space’.Footnote 106

These secrecy practices, though often understood as a ‘blank spot’, can also be understood as part of US (as well as other colonial) foreign policy practices that have long invested in spectacle in the effort to influence. In other words, as this work suggests, ‘dominance by design’ and the spectacle of war as foreign policy – the showcasing of technology, military or otherwiseFootnote 107 – also takes place through these secrecy practices. Returning to Michael Leeder on magic, demonstrations of secrecy are also efforts to show the foreign ‘other’ and the ‘self’ that ‘we are superiors in everything’.Footnote 108 Using the memoir of French magician turned envoy, M. Robert-Houdin, and the 1856 mission to Algeria to quell Algerian resistance with a show of French force through his illusion show, Leeder argues that Robert-Houdin's shows served multiple functions: to reproduce ideas about ‘the savage colonial’Footnote 109 as well as to reproduce ideas about French rationalism and modernity for ‘others’, and the benefits to ‘others’ of adopting French ways, allowing ‘Europeans to confirm their own modern advancement by casting Algerian natives in the inferior role.’Footnote 110

US Special operations, as presented in these memoirs, can be read in the same way. Secrecy practices therefore can be understood as part of a longer-term and larger set of US foreign policy practices that reproduce ideas about the ‘self’ and ‘others’. As President Bill Clinton allegedly claimed in 1996, following reports that al-Qaeda had relocated to Afghanistan, ‘you know it would scare the shit out of al-Qaeda if suddenly a bunch of black ninjas rappelled out of helicopters into the middle of their camp. It would get us enormous deterrence and show the guys we're not afraid.’Footnote 111 Secrecy practices – whether constructing the foreign ‘other’ or the self as insider, stealthy, quiet, and alluring subjects – therefore helps to reproduce the logic of the GWoT security discourse as a multilayered composition. Secrecy's power is also secrecy’s subjects.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of the article were presented at the International Studies Association Annual Convention and at the Composing Global Security Workshop in San Francisco in 2018. I would like to thank Debbie Lisle, for thoughtful and engaged comments on an early draft, as well as the support and comments of the excellent members of SPIN, the Secrecy, Politics, and Ignorance Research Network, including Brian Rappert, Oliver Kearns, Clare Stephens, and the participants at the ‘Secrecy and (In)Security’ Workshop in Bristol. My thanks also to Kate Byron, Clare Stephens, Javiera Correa, Natalie Jester, Stuart and Georgina for lifesaving research assistance, and to the EJIS Editor Tim Edmunds, the Special Issue Editor Jonathan Luke Austin, and the reviewers for helpful advice and support.

Elspeth Van Veeren is a Senior Lecturer in Political Science in the School of Sociology, Politics, and International Studies at University of Bristol. Specialising in the security cultures, politics, and foreign policy of the United States, and in particular on the visual and material dimensions of meaning-making in security discourses, she has published work on torture, US detention practices at JTF Guantánamo, and on art and conflict. Her more recent work is an exploration of secrecy cultures, invisibilities and ignorance, and the practices of ‘manhunting’ in the second decade of the Global War on Terror. Elspeth is a co-convener of SPIN, the Secrecy, Politics and Ignorance Research Network based in the UK.