Introduction

Racism in the USA has roots that extend deep into the history of both healthcare and medical research [Reference Bailey, Feldman and Bassett1–Reference Elias and Paradies4]. The systemic oppression of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in our healthcare system and their exploitation by researchers has existed since the time of enslavement and continues to this day.

“The most difficult social problem in the matter of Negro health is the peculiar attitude of the nation toward the well-being of the race. There have… been few other cases in the history of civilized peoples where human suffering has been viewed with such peculiar indifference.” W.E. B. Du Bois (1899)

Over 120 years ago, American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois highlighted the connection between social inequities and health inequities and consequently the prevalence of poorer health for Black Americans [Reference Du Bois5]. To this day, that health divide caused by structural racism still remains irrefutable. Black people do not live as long [Reference Arias, Tejada-Vera and Ahmad6]. They have higher rates of hypertension, cancer, diabetes, and heart disease than other groups [Reference Dyer7]. Critically examining and acknowledging the history of racism in our healthcare and research systems is crucial to closing the health equity gap.

It is vital that Learning Health Systems adapt and function in ways that directly prioritize equity [Reference Parsons, Unaka and Stewart8]. Learning Health Systems are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation as networks that aim to transform healthcare and research via evidence-based knowledge generation, continuous learning, and broad stakeholder engagement [Reference Friedman, Rubin and Brown9]. At the University of Rochester Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UR CTSI), in collaboration with our community partners, we have successfully developed and disseminated a community-based participatory research (CBPR) training program, adapted from the Columbia University Irving Institute model, that has been transformative for both community partners and university researchers who have completed the program. Our UR CTSI Community Engagement Function benefits from its close association with the Center for Community Health and Prevention (CCHP) which is a model for community engagement and team science, and whose mission statement includes “To join forces with the community to promote health equity; improve health through research, education and services, and policy.” Utilizing this unique relationship, our Community Engagement Function worked closely with the CCHP to build upon the success of the CBPR Training Program. While a small part of the curriculum for this training program included the history of racism in research, we recognized the need to expand on this content and offer a more comprehensive and complete educational experience. As we strive to build community partnerships, as an institution we continue working to build and repair trust with people from all backgrounds, and it is imperative that we acknowledge and address the dark history of racism in healthcare and research. In addition, to further strengthen UR researcher and community member capacity to collaborate in research through new educational offerings, we sought to develop and deliver an educational program that provides a foundational knowledge of the history of racism in healthcare and research. The objective of the course was for participants to understand that racism, and not race, causes health disparities and why mistrust of the healthcare system and the long history of their exploitation in research is the primary reason for some BIPOC not participating in research studies.

Course Development

Building upon our innovative approach to curriculum development and delivery for our CBPR Training Program that engaged both UR research faculty and community research partners, we applied the Public Health Critical Race praxis (PHCR) that draws upon the robust body of antiracism work that exists outside of public health [Reference Ford and Airhihenbuwa10]. One tenet of PHCR is “outsiders within,” describing individuals who are members of their respective discipline but are often marginalized within it because of their social identity [Reference Hardeman11]. By grounding themselves in the experiences and perspectives of their social identity, these “outsiders within” integrate critical analysis of their lived experience into their respective discipline [Reference Ford and Airhihenbuwa12]. Another central tenet of this work was trustworthiness [Reference Frerichs, Kim and Dave13] utilizing the practices of accountability and transparency. A goal of the academic/community partnership planning group was to communicate honestly and openly about power dynamics and bias while attempting to shift them. This transparency was also present in interactions with course participants. With shared agreements, the facilitation team and participants held ourselves and others accountable for words and impact.

Academic/community partnerships developed from individual relationships have fostered increased understanding of racist practices and the will to change. As organizing principles, these have informed future action. The development of the Structural Racism in Healthcare and Research course was both a response to these factors and an initiative to acknowledge and transform the future of practice.

The first step in determining community partner interest in leading course creation and implementation was sending a request to the local African American Health Coalition and Latino Health Coalition, asking for members who have a knowledge of the history of racism in healthcare and research and a commitment to community health and multi-directional learning. Through this solicitation, six BIPOC community members responded – five identifying as Black and/or African American and one identifying as Hispanic/Latinx; all identify as women.

Each facilitator brought their unique lived experience within the local community, along with decades of professional experience in health and mental health education, organizational management, clinical practice, and passion for eliminating disparities. Additionally, the combination of lived and professional experience meant each facilitator understood the ways in which structural racism influences health disparities in communities of color. Each of the six members of the facilitation team had previously worked with the UR CTSI in some capacity; this social capital came as a result of connection to the CBPR program and personal connections. Aligning with the PHCR “outsiders within” principle, the UR CTSI held space for the facilitators to have creative freedom in the curriculum development process. As all group structures benefit from clarity with regard to leadership, roles, and norms to ensure effectiveness and efficiency, one person among the six was designated the lead facilitator.

Identifying professionally as a clinician and educator who had a dual background working both in community health and as a PhD student at the University of Rochester, Warner School of Education, TT, (who was later recruited to URMC) volunteered to act as the lead facilitator of the curriculum development meetings. In this role, she integrated knowledge of cultural humility [Reference Tervalon and Murray-Garcia14] and critical race theory [Reference Delgado and Stefancic15, Reference Ladson-Billings and Tate16], into the modules and leadership role, as it related to leading the team of facilitators. In this role, the lead facilitator balanced structure and flexibility to support the group in identifying areas of personal interest and expertise. She led group decision-making regarding ways to scaffold and integrate the curriculum modules, as well as determining the length of each module, delivery, and modality.

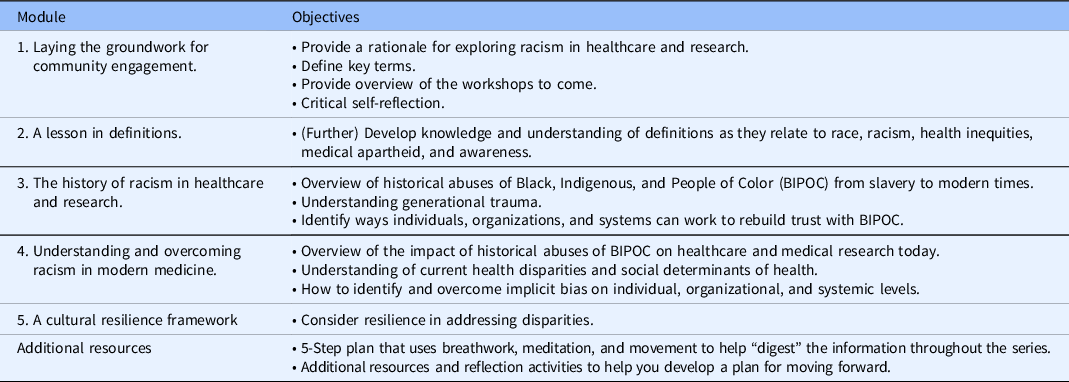

Over an eight-week period, during spring 2021, the facilitators met weekly as a group with additional meeting times designated for facilitators to work independently or in pairs on their respective modules. These weekly meetings were convened by two UR CTSI Community Engagement Function and CCHP staff members (JC and LS) who were present, not to facilitate or direct the discussions, but rather to answer any strategical or logistical questions from the facilitators. Grounded in the work of Harriet Washington’s (2006) Medical Apartheid [Reference Washington17], each facilitator had the creative freedom to decide the topic and content to be covered in each session. Based on a transformational theory [Reference Mezirow18] of change, the SRHR curriculum was developed considering the various conditions that work to maintain systems of oppression and structural racism. This premise finds value in experiences of discomfort, identifying them as a catalyst for change. According to the theory, it is through discomfort that transformation can occur on 3 levels: (1) psychological (view of self-in-relation to other); (2) convictional (individual belief systems); and (3) behavioral (one’s actions). Structural change relies on both relational (i.e., power dynamics) and intra-personal change [Reference Kania, Kramer and Senge19]. Hence, lecture, small group discussion, reflection, and practice were intentionally integrated into each session. This multimodal approach gave attention to the need for shifts in individual mental models, the interpersonal actions stemming from these beliefs, and the policies/procedures that codify racist ideas. Together, the team determined the order in which topics would be covered, the length of each session, and the mode of content delivery (i.e., via live Zoom, pre-recorded, in-person). In sum, five, 90-minute modules were developed (Table 1).

Table 1. Course overview with module description and objectives

Topics included the following: Module one, “Laying the Groundwork for Community Engagement,” was an introductory module providing the rationale for focusing on structural racism in healthcare and research. In addition to relationship-building and establishing group norms, module one gave a sense of context by exploring racism as a public health crisis, shifting the focus from the individual to the systems and structures influencing the way people live and die. In recognizing the importance of a common language when teaching and learning about such topics, module two, titled “A Lesson in Definitions,” focused on defining key terms for the purpose of building participants’ knowledge and understanding of definitions as they related to race, racism, health inequities, and medical apartheid.

Modules three and four titled, “The History of Racism in Healthcare and Research,” and “Understanding and Overcoming Racism in Modern Medicine,” respectively, were the most content heavy: heavy in relation to both the amount and intensity of the content. These workshops provided accounts of historical abuses in healthcare and research of people identifying as BIPOC from enslavement to present times. The specific objectives of module three included the facilitation of participants’ development of a general understanding of the historical abuses of BIPOC in healthcare and medical research from enslavement to modern times. Additionally, module three aimed to develop participants’ understanding of intergenerational trauma, as well as supporting them in identifying ways individuals, organizations, and systems can work to build trust with BIPOC individuals and communities. Module four focused on further developing participants’ understanding of the impact of historical abuses of BIPOC on healthcare and medical research today. In addition, topics such as social determinants of health and health disparities were covered. It was important to the facilitators that the workshop content covered topics not only to facilitate awareness but to compel participants to take action. For this reason, discussions such as identifying and challenging implicit bias and ways to rebuild trust with communities of color were included in module four. As such, the final objective of module four was to further support participants in identifying and responding to racism and implicit bias on individual, organizational, and systemic levels.

Finally, recognizing that it is possible for teaching focused on dismantling structural racism to actually propagate racist ideas [Reference Blake, Ioanide and Reed20], it was imperative for the facilitators to end the series with a focus on resilience. To be clear, despite the historical and contemporary experiences of trauma that people identifying as BIPOC have endured over centuries, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color are still here. Thus, module five, the final workshop titled, “A Cultural Resilience Framework,” focused on cultural humility and the community and cultural wealth model [Reference Yosso, Solórzano, Romero and Margolis21]. Through her work in critical race theory, Yosso (2005) shifted the lens away from a deficit view of communities of color as places plagued by poverty and disadvantage, and instead focused on and learned from the array of cultural knowledge, skills, abilities, and contacts possessed by socially marginalized groups that often went unrecognized and unacknowledged. Because everyone belongs to a larger society in which racist ideas are perpetuated, no one is immune from the cultural conditioning that instills biases and prejudices that discriminate against People of Color, even as persons of color [Reference Sue, Capodilupo and Torino22, Reference Terrance23]. As such, it was incumbent upon the lead facilitator to engage in critical self-reflection with regard to the components of her own social identity that afford access (privilege) and act as barriers (oppression), while also facilitating that process with the team. The community and cultural wealth model articulates six forms of capital originating within communities of color, each of which was used to challenge workshop participants in thinking of the ways such capital is demonstrated by/in which the patients or communities with whom they work.

Course Implementation

The five-module course pilot took place over five weeks in Fall 2021. This free course was open to University of Rochester faculty, staff, trainees, and students associated with research as well as community members (typically from community-based organizations) and was advertised widely through our own university networks, listservs, and newsletters and also by our partners at local community-based organizations. Approximately one hundred individuals registered their interest in completing the course, and ultimately, 12 community members and 12 university researchers were chosen at random to participate. The course was delivered on a virtual platform with two co-facilitators leading each module for 90-minutes and included a mixture of didactic presentation and breakout sessions. Co-facilitators were also joined by the same two UR CTSI Community Engagement Function and CCHP staff members (JC and LS) who offered remote platform technical assistance and other logistical support.

All course participants had shared interests and goals around in-depth learning about structural racism in healthcare and research and therefore the group progressed through this course as a supportive peer learning community learning from and with each other [Reference Boud and Cohen24]. Each individual’s contribution to the discussion based on their lived experience, intersectional identities, and cultural background was heard and valued. Additionally, because a lot of the curriculum addressed sensitive and potentially triggering topics, we incorporated breath work, meditation, and movement throughout all modules of the course.

Community-academic partnerships continue to struggle around issues of equitable compensation for community member’s expertise and time due to a mismatch in resources mirrored by traditional university systems that value the degrees earned by academics more than the years of experience earned by community members [Reference Black, Hardy and De Marco25]. To further reinforce an equitable power structure course, facilitators were financially compensated for all time spent on the project, including group planning meetings.

Evaluation and Process Improvement

A course evaluation survey was designed and pretested across multiple iterations, incorporating feedback from course facilitators and survey experts. Four community members and one university researcher who attended three or fewer sessions were not considered “graduated from the course” and did not receive an evaluation survey. Two weeks after completion of the course, the evaluation survey was sent to all participant to examine how well the meeting goals were achieved. All attendees received an initial email invitation with a link to the survey and two subsequent weekly reminders. The survey was designed to elicit ratings of attendees’ perceptions of content-specific learning objectives. It also included open-ended questions, for which attendees were asked to describe the most helpful aspects of the course and what aspects they would recommend to others.

For analysis of survey results, responses were de-identified, and personal identifiers were removed. Means, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated for demographic and quantitative survey response items. The generated data of this study were summarized as a mean with standard division wherever applicable. A paired t-test was conducted to compare the response scores of participants before and after the online survey. Multiple test adjustment was not applied due to the explorative nature of this study. Statistical significance was defined as P-value <0.05 (two-sided). Statistical analyses were performed using Software SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

For analysis of the qualitative results, procedures included establishing a general framework for data analysis (open coding of themes and specific quotes related to domains of interest). Then, a structured process to associate self-reported constructs (axial coding) led to the development of specific categories and sub-categories based on established qualitative research methodology for theme coding developed by Strauss & Corbin [Reference Strauss and Corbin26] and similarly employed in our recent work [Reference DeAngelis, McIntosh, Ahmed and Block27, Reference McIntosh, Coykendall and Lin28]. Specific representative quotations were placed into a spreadsheet to aid analysis. One reviewer with experience in qualitative theme coding (SMc) reviewed and assigned each individual response to initial themes. A second coder (LS) reviewed and confirmed the emerging themes. The study team then reviewed and confirmed final themes and conclusions.

Evaluation Results

At the conclusion of the online data collection, 14 responses were received from the total of 19 attendees, for a final response rate of 73.68%. All of the respondents self-reported as women (n = 14; 100%). Two respondents were Asian (14.3%); six were African American (42.9%); and six were white (42.9%). Regarding ethnicity, one respondent self-reported as Puerto Rican (8.3%). Of the 13 respondents who described their affiliation, eight (61.5%) selected University of Rochester (8, 61.5%), and five (38.5%) selected community partner/member.

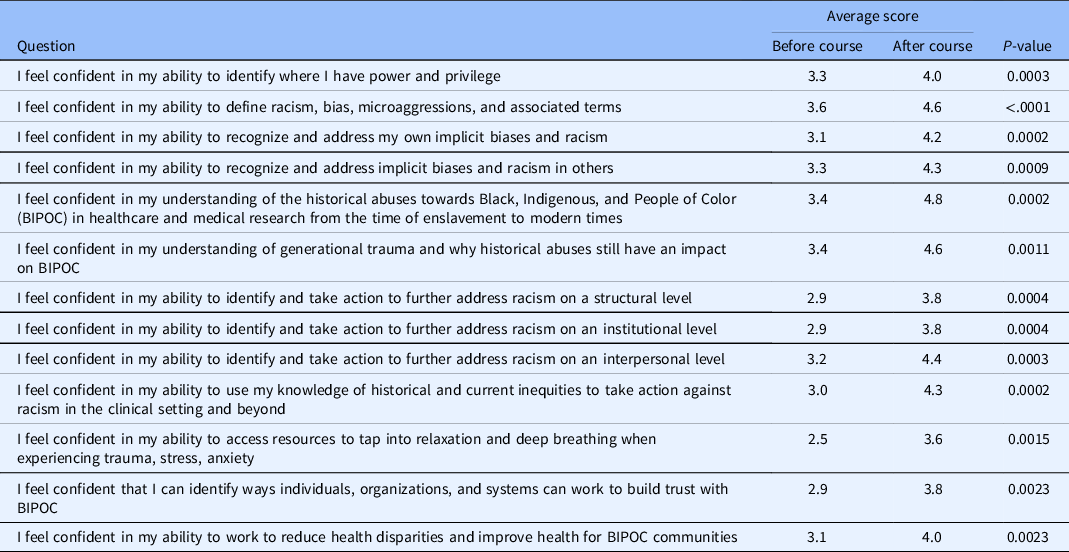

Participants responded to questions in terms of how true it is for you with respect to their learning in this course using the scale: 1–5, where 1 is not at all true, 3 is neutral, and 5 is very true. Results demonstrated a significant increase in participant’s knowledge related to racism in healthcare and research and their ability to identify and take action to address inequities related to racism at an interpersonal and institutional level and inequities in healthcare and research after the course when compared to before the course for all 13 questions (Table 2).

Table 2. 2-week post-course participant evaluation survey results. Ratings based on a scale: 1–5, where 1 is not at all true, 3 is neutral and 5 is very true

Also, most of the respondents (n = 13; 92.86%) agreed or strongly agreed that the course aligned with their expectations. The respondent who felt the course did not align with expectations felt there should be more of a focus on the evidence base and recommended action steps based on current context, rather than the course being focused on building interpersonal relationships.

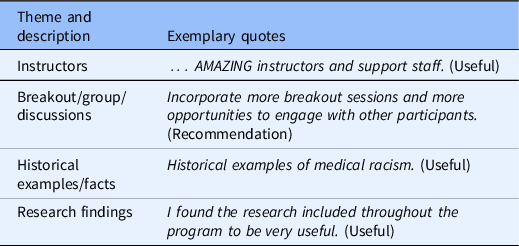

Common themes relevant to what respondents liked about the course and/or reasons for recommending it to others included the following: (1) good instructors; (2) group discussions; (3) basis in research; and (4) use of historical examples (Table 3). The types of persons for whom they would recommend the course included persons in health, higher education, and faith-based fields, including administrators, faculty, and staff.

Table 3. 2-week post-course participant evaluation survey results – common themes and exemplary statements

Discussion

Cultural humility is a way of being that begins with critical self-reflection. Inherent in such criticality is the understanding of one’s own cultural knowledge and the ways in which this knowledge influences the interpersonal dynamic, for better or worse. For instance, it was imperative to know that when working with People of Color, relationship is primary; thus, time spent among the team of facilitators getting to know one another personally as well as professionally throughout the curriculum development process was crucial when it came to idea sharing, decision-making, and navigating differences in style and opinion.

Additionally, understanding one’s own knowledge base is to also understand the ways in which such knowledge is influenced by racist ideas [Reference Kendi29]. The recognition of racism as a permanent component of American life that operates on institutionalized, interpersonal, and internalized levels [Reference Brown30–Reference Speight32] was central to the framework of course creation and facilitation [Reference Kendi29] – based on one’s assumptions, stereotypes, and prejudices.

Moving forward, a cultural humility orientation also emphasizes the reality that there are limits to one’s knowledge; thus, a sense of openness or receptivity within the context of differing ideas and opinions is needed. In illustrating the dynamics involved in working across difference, Chavez et al. (2008) used the metaphor of dancing. Within the context of curriculum development, this “dance” required the lead facilitator to find a balance between leading and following, navigating her role in a manner that did not step on others’ toes, and in instances when toes did get stepped on, the lead facilitator had to move through her own defensiveness, and decide whether to continue dancing or take a seat [Reference Chavez, Duran, Baker, Avila, Wallerstein, Minkler and Wallerstein31]. It was through this practice of “stepping-up/stepping-back,” that a cultural humility orientation demonstrated and modeled by the lead facilitator’s intra-personal process of critique and perspective-taking ability translated inter-personally into humble actions, thus facilitating the group’s ability to navigate the curriculum development process.

The relationship between our UR CTSI Community Engagement Function and CCHP staff and the community partners who developed and facilitated the course goes beyond only co-creating and implementing the course. This partnership was truly community-engaged, being mutually beneficial with bi-directional communication that was open and honest and is a relationship that can serve as a best practice model for partnerships between community members and organizations. As a result of comments on participants’ experience with the pilot, the team used feedback from the evaluation to make changes to the format of the second iteration of the course. This included the addition of an introductory module that was attended by all co-facilitators and the UR CTSI Community Engagement Function and CCHP staff. Furthermore, discussion forums were added between modules three and four and after the final module. The ability to talk openly and in a brave space about personal beliefs, biases, and action impacted attendees personally and advanced the cohort together. This course is a step in the dismantling of racism in healthcare and research spaces led by trusted community partners. The class will be offered at least once each year and continue to be open to both researchers and community partners. Future development of the course will strive to provide even more opportunities for participants to formulate actionable strategies and plans to address institutional and structural racism, feedback that has come directly from participants themselves.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the following: Alfred Vitale and Edwin Van Wijingaarden for support and guidance for course creation, educational objectives, and evaluation of facilitator experience; Amatul Musawar Ahmad for organizational support, including operating Google Classroom; Jiaya Pang for survey design; Sanjukta Bandyophadhyay for statistical analysis of quantitative survey measures; and all of our families for later than usual dinners and making sure we could focus on this work.

The project described in this publication was supported by the University of Rochester CTSA award number UL1 TR002001 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (JC, LS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no declarations of any conflicts of interest.