1 Overview

In 2014, a Chinese-financed company, Société Minière de Boké (SMB), contracted with the Guinean government and obtained three mining concessions to exploit bauxite reserves in Boké, Guinea.Footnote 1 Since then, SMB has had a tumultuous history working in Boké, with local residents complaining of copious amounts of dust being generated, depleted and polluted freshwater sources, and a reduction in farming capacity due to pollution and lack of fresh water. These environmental issues have also led to adverse health impacts within local communities, including respiratory illnesses as a result of excessive dust. However, despite these controversies, SMB’s presence in the country has grown. In 2015, SMB began construction of major mining infrastructure, including roads and ports,Footnote 2 and in 2020, preparation for the construction of an alumina refinery and a coal-fired power plant in Boké started.

SMB’s operations in Guinea raise important questions about the Chinese leadership’s commitment to green and sustainable development in China’s overseas projects. The construction of the fossil fuel power plant continued after Chinese President Xi Jinping’s public statement in 2021 that “China will vigorously support the green and low-carbon development of energy in developing countries and will no longer build new overseas coal power projects.”Footnote 3 Civil society organizations have made efforts to force SMB to use a cleaner energy source to power the refinery. Such efforts draw attention to the gap between rhetoric and reality in China’s overseas projects.

This case study focuses on how local and international civil society organizations and public interest lawyers use legal instruments to ensure Chinese investors and the Guinean government comply with the laws of Guinea (as the host country of Chinese investments), of China (the home country), and international laws. Specifically, this case study shows how civil society organizations have been able to combat SMB’s plan to use coal as an energy source by recourse to a number of legal strategies. More broadly, it demonstrates how non-state actors can use the law to hold Chinese investors accountable for environmental harms inflicted on host states, particularly those in the Global South.

The case study is written by members of an advocacy NGO that is leading actions against SMB for violating relevant laws. While procedures are still pending, the case study provides both the history of the project and a snapshot of current problems.

2 Introduction

2.1 Guinea Country Profile

The target project, the alumina refinery and proposed coal-fired power plant, is located in the Boké prefecture of the Republic of Guinea. Guinea is a West African country located on the Atlantic Ocean and bordered by Sierra Leone, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali. Boké prefecture is located in the northeastern part of the country and is home to more than 480,000 people in ten subprefectures that are composed of twenty-four distinct village communities.Footnote 4

The major exploitable mineral resources in Guinea include bauxite, iron, diamonds, gold, and uranium.Footnote 5 Guinea contains a third of all known bauxite reserves in the world and SMB is the largest producer of bauxite in the country.Footnote 6 Bauxite is needed to produce aluminum, and China is the world’s largest producer of aluminum, thus its access to Guinea’s mines is an economic imperative. However, the main economic activities in the region include subsistence agriculture, fishing, salt farming, livestock, and handicrafts – all of which are threatened by bauxite mining activities.Footnote 7 Despite Guinea’s copious natural resources and bauxite reserves, it is one of the poorest countries in the world.Footnote 8

The country’s current predicament reflects a complicated history. Guinea achieved its independence from French West Africa in 1958.Footnote 9 After gaining independence, Guinea was ruled by authoritarian leaders, Sékou Touré, Lansana Conté, and Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, for more than fifty years.Footnote 10 In 2010, for the first time since gaining its independence from France, Guinea conducted elections to choose its next ruler, President Alpha Condé.Footnote 11 A new constitution was passed in 2010 and then again in 2020.Footnote 12 These legal reforms had limited effect on the mining industry, which has been central to the country’s economy.

Condé expanded the mining sector, particularly the bauxite mining sector, during his time as president and promulgated a new mining code meant to improve mining regulations and increase profits for the government from mining.Footnote 13 However, the bauxite mining sector faced some initial setbacks during Condé’s first term, including resistance from companies that, as a result of the new regulations, had to pay higher taxes (the 2011 Mining Code was amended in 2013 because of this issue), the Ebola epidemic, and low global prices for bauxite.Footnote 14 The bauxite sector boomed after Condé’s first term in office after other bauxite-producing countries banned exports and Chinese demand for bauxite increased.Footnote 15

Condé ran for and won a contentious third term in 2020 and remained in power until he was overthrown by a military coup in late 2021.Footnote 16 The ruling military junta suspended the 2020 Constitution and instituted a Transitional Charter with Col. Mamady Doumbouya serving as the transitional president.Footnote 17 As of 2023, Guinea’s ruling military junta has yet to conduct elections to determine the country’s next leader. It is also worth noting that the Natural Resource Governance Institute has consistently given Guinea low scores in the category of rule of law; in 2021, Guinea received a ranking of just 15 out of 100.Footnote 18

2.2 Guinea–China Relations

In the past decade, Guinea and China have deepened their relations. In November 2016, President Condé paid a state visit to China to meet with President Xi Jinping. The two heads of state decided to establish a comprehensive strategic partnership and to take the implementation of the outcomes of the 2015 Johannesburg Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) as an opportunity to deepen and expand friendly and mutually beneficial cooperation between the two countries in various fields and create a broader future for China–Guinea relations.

In September 2017, China and Guinea signed the “China-Guinea Resource and Loan Cooperation Framework Agreement” in Xiamen, China.Footnote 19 In the agreement, Guinea granted Chinese corporations exploration rights for bauxite, iron, and other mineral resources, while China agreed that Chinese financial institutions would provide the necessary loans for the extraction projects.Footnote 20 The agreement notes that over the next twenty years (2017–2036) the amount of money invested in mining projects in Guinea by China would reach US$20 billion.Footnote 21 A list of priority projects added as an addendum to the agreement includes bauxite mining projects in Boffa and Boké.Footnote 22 Overall, this resource for infrastructure agreement seeks to accelerate China-financed extraction of mineral resources in Guinea.

In September 2021, after the military coup overthrew President Condé from office, Chinese companies remained active in Guinea. However, the Chinese government condemned the coup and urged for the immediate release of President Condé.Footnote 23 A spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, Mr. Wang Wenbin, stated in a press conference concerning the coup that “[w]e hope relevant parties can exercise calm and restraint, bear in mind the fundamental interests of the nation and people, resolve the relevant issue through dialogue and consultation and safeguard peace and stability in Guinea.”Footnote 24

2.3 China’s Climate and Biodiversity Commitments in the Context of Chinese Laws and Policies on Outbound Direct Investments

China’s outbound direct investments regime is designed with the objective of safeguarding state-owned assets and their financial security. The environmental and social impact of offshore projects has not been a core concern of the Chinese government, and as such, there is no legislation with enforcement effect to screen the environmental and social impact of overseas investment projects. In addition, institutionally, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the main administrative agency in charge of environmental affairs in China, does not have the mandate to regulate overseas projects.Footnote 25

Recognizing the threat that climate change poses, China has made significant commitments to reduce emissions in its international investments, particularly in developing nations. In 2021, FOCAC published the “Declaration on China-Africa Cooperation on Combating Climate Change.”Footnote 26 The Declaration states that both China and African countries will advocate for and advance sustainable development and will “promote ‘green recovery’” in a post-COVID economy. Further, China commits to promoting low-emission technologies in Africa, including solar and wind-powered energy production. The Declaration also states that China “will not build new coal-fired BRI power projects abroad.” China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has made similar commitments to sustainable development in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).Footnote 27 Specifically, the NDRC commits China to promoting green energy in its operations abroad linked to the BRI,Footnote 28 stating that “[e]nterprises shall be encouraged to promote green and environmental protection standards and best practices for infrastructure.” Additionally, the NDRC notes in their opinion that “the full implementation” of China’s and participating African countries’ commitments under international climate agreements including the Paris Agreement shall be promoted.Footnote 29 The NDRC further states that “[t]he construction of overseas coal-fired power projects shall be completely stopped.”

China made similar goals for green international development in the notice by the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment on issuing the “Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation.”Footnote 30 An enumerated goal for Chinese outbound investment stated in the guidelines is to “support outbound investment in clean energy such as solar, wind, nuclear and biomass energy, facilitate the global revolution of energy production and consumption, and build a clean, low-carbon, secure and efficient energy mix.” In September 2021, at the 76th UN General Assembly, President Xi Jinping stated, “China will vigorously support the green and low-carbon development of energy in developing countries and will no longer build new overseas coal power projects.”Footnote 31 Further, China reiterated the goal to not build any new coal power plants abroad in the communication to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) on China’s Nationally Determined Contributions.Footnote 32

2.4 Guinean Governmental Structure on Mining, Natural Resource Management, and Environmental Matters

While conducting mining operations in Guinea, SMB not only should abide by the laws and policies of China but is legally bound by the laws of the Republic of Guinea in relation to the environment and human rights. Institutionally, both the Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable/Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD) through the Guinean Environmental Assessment Agency (AGEE) and the Ministry of Mines and Geology have oversight of mining projects and the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) process in Guinea.

2.4.1 Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development and the AGEE

The AGEE coordinates the administrative procedure of the mining projects’ ESIAs and audits in Guinea. It approves the terms of reference of all ESIAs submitted by the companies as a first step, receives the ESIA reports, and organizes public audiences with local stakeholders to ensure that the members of communities who may be affected can participate in the ESIAs and are aware of the conclusions. It is responsible for approving the ESIAs through the Comité Technique d’Analyse Environnementale/Technical Committee for Analysis and Assessment (CTAE). The CTAE is a committee formed by the MEDD and coordinated by the AGEE. The CTAE is composed of members of ministerial departments and civil society representatives.Footnote 33

Additionally, the Comités Préfectoraux de Suivi Environnemental et Social/Prefectural Committee for Environmental and Social Monitoring (CPSES) was set up by the Ministry in charge of the MEDD to support the AGEE in its mission of monitoring the implementation of the projects’ Environmental and Social Management Plans (ESMPs). The CPSES is represented in all prefectures where mining projects occur. It provides close monitoring for certain environmental and social components of mining projects being developed in the territories covered by their activities.

The AGEE carries out the monitoring and audits of the projects’ ESMP and delivers, on behalf of the MEDD, the environmental compliance certificate for “Category A projects” (projects that have significant impacts on the environment) and environmental authorization for “Category B projects” (projects that have less effect on the environment).

2.4.2 Ministry of Geology and Mines

The Service National de Coordination des Projets Miniers/National Service for the Coordination of Mining Projects (SNCPM) coordinates the feasibility studies of all mining projects, which consists of evaluating both the technical feasibility and the economic viability of a project. The feasibility report is submitted to the Ministry of Mines and Geology through the SNCPM for the project evaluation and approval. The Direction Nationale des Mines/National Directory of Mines is in charge of monitoring the mining production and all related taxes while the Centre pour la Promotion et du Développement Minier/Center for the Promotion of Mining Development is responsible for managing the Guinean mining cadastre. The service delivers mining permits and authorizations for research, exploration, and exploitation activities.

2.5 Guinean Environmental Laws and Decrees

The Guinean legal system is highly influenced by its history of French colonization and prescribes a civil law system. The relevant sources of Guinean law that provide the framework for regulating the mining industry include the Guinean Constitution of 2010 and 2020, as well as the Transitional Charter, the Environmental Code of Guinea 2019 and implementing regulations, and the Mining Code and implementing regulations.

The Constitution of Guinea guarantees the right to a healthy environment along with other environmental protections.Footnote 34 Article 16 of the 2010 Constitution states, “[e]very person has the right to a healthy and lasting environment and the duty to defend it.”Footnote 35 As mentioned, in 2020, a reformed constitution was passed by referendum.Footnote 36 The 2020 Constitution contains a similar right to a clean and healthy environment in Article 22, which states in part that “[t]he right to a healthy environment is recognized throughout the territory.”Footnote 37 After the 2021 coup, the ruling military junta suspended the 2020 Constitution and instituted a Transitional Charter. Because the SMB project began in 2014, all three texts (2010 Constitution, 2020 reformed Constitution, and the Transitional Charter) apply. The Transitional Charter does not contain any explicit protections for the environment.Footnote 38

The Environmental Code of Guinea 2019 sets out a few basic overarching policies when it comes to environmental protection and energy generation. Generally, it promotes environmental sustainability, the consideration of climate issues, and the use of renewable energy. The Code places explicit duties on private companies operating in the extractives sector in Guinea, noting in Article 16 that “[p]rivate enterprises and public and mixed companies carrying out industrial and/or commercial activities shall be required to integrate environmental concerns into their operating, production and responsible management systems, meeting the requirements of sustainable development.”Footnote 39 Article 9 of the Code notes that development projects in Guinea must take into account the importance of environmental protection and must adhere to several principles of environmental stewardship including, among others, the precautionary principle and the principle of sustainable development.Footnote 40

Procedurally, the Environmental Code specifically requires that projects having an impact on the environment perform an ESIA.Footnote 41 Article 142 of the Mining Code also requires that mining companies complete an ESIA as a part of the application for an Authorization or Operation Permit and that the ESIAs prepared by companies abide by the Environmental Code and meet “internationally accepted standards.”Footnote 42

According to Article 31 of the Environmental Code, “[w]hen the environmental and social impact study is deemed to be satisfactory, the minister in charge of the environment shall issue to the developer a certificate of environmental compliance.”Footnote 43 Guinean regulations concerning ESIAs require that after the completion of the study period for the ESIA, a report (an environmental and social impact study report, known as REIES) must be submitted to the Ministry in charge of the environment for review by the CTAE.Footnote 44 If the REIES is approved by the CTAE, the minister in charge of the environment must issue the environmental authorization or the environmental compliance certificate (certificat de conformité environnementale).Footnote 45 Article 22 of Order A/2022/MEDD/CAB/SGG of 25 July 2022 on the administrative procedure for environmental assessment states that the environmental compliance certificate, which is granted by the minister of the environment on the recommendation of the CTAE, is valid for one year and is renewable each year.Footnote 46

Additionally, as part of the ESIA process, companies operating in Guinea must produce an ESMP.Footnote 47 The ESMP is a document that lays out the procedure for managing, implementing corrective or mitigation measures, monitoring, and following up on the environmental and social risks and impacts in preparation for and during the project that operating companies must adhere to.Footnote 48 Each year, the company must submit an ESMP implementation report to the AGEE. This yearly report is a requirement for the renewal of the environmental compliance certificate.

2.5.1 The Use of Guinean Law by Civil Society

The accessibility of the judicial system by civil society organizations or impacted communities remains a challenge to be met in Guinea. Article 24 of the Environmental Code guarantees access to justice to “the State and the local collectivities; any company working in the field of the environment; and any approved association in the field of the environment; any natural person having a sufficient interest to act.” Further, Article 19 of the Environmental Code allows for environmental protection organizations to challenge any administrative act that may have a significant impact on the environment. Despite these legal guarantees, in practice, often access to justice is not granted. Specifically, as of the time of this writing, no administrative environmental action has been brought to the Guinean courts.

2.6 International Treaties and Standards

Both China and Guinea are signatories of the UNFCCC. Article 3 of the UNFCCC states in part that “[t]he Parties should take precautionary measures to anticipate, prevent or minimize the causes of climate change and mitigate its adverse effects.”Footnote 49 Additionally, the Guinean ESIA regulations note that companies should adhere to national standards when conducting ESIAs, but when national standards are absent, companies should follow international best practices, specifically mentioning the International Finance Corporation (IFC) standards.Footnote 50 The IFC standards aim to guide corporations on best practices to ensure that environmental and social rights of affected communities are respected and preserved.

IFC Performance Standard 3 concerns “Resource Efficiency and Pollution Prevention.”Footnote 51 A key objective of IFC Performance Standard 3 is “[t]o reduce project-related GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions.”Footnote 52 In relation to GHG emissions, IFC Performance Standard 3 instructs companies to consider less polluting alternatives to energy generation stating, “the client will consider alternatives and implement technically and financially feasible and cost-effective options to reduce project-related GHG emissions during the design and operation of the project.”Footnote 53 The standard goes on to note that a reasonable project alternative may include “adoption of renewable or low carbon energy sources.”

Further, the IFC Performance Standards make reference to the World Bank Group Environmental, Health and Safety Guidelines (EHS Guidelines) and note that the EHS Guidelines are “technical reference documents with general and industry-specific examples of good international industry practice.”Footnote 54 The IFC Performance Standards note that when the standards of a host country differ from standards presented in the EHS Guidelines, the company should abide by whichever standards are more stringent.Footnote 55

3 The Case

The Société Minière de Boké was founded in 2014 by the SMB Winning Consortium, a consortium of companies including the Shandong Weiqiao/China Hongqiao Group Limited, Winning International Group of Singapore, Yantai Port Group, and United Mining Supply of Guinea.Footnote 56 SMB’s operations in Guinea include four bauxite mining sites, a railway, two ports, and two mining roads. SMB is the leading producer and exporter of bauxite in Guinea, responsible for about 40% of bauxite production in 2020 (see Figure 6.1.1).Footnote 57 Additionally, SMB is planning on building an alumina refinery; construction was set to begin in 2023 but has been delayed. The refinery will be powered by a captive coal-fired power plant. SMB began the ESIA process in September 2020 for the refinery project. SMB completed the ESIA in February 2021 and the report was validated and given an environmental compliance certificate in April 2021 after a virtual session organized by the validation committee (CTAE). The ESIA conducted by SMB combined both the refinery and the coal plant projects but did not independently assess the impacts of the coal plant. The planned coal plant is a “captive coal plant,” meaning that the energy produced from the coal-fired power plant will only be used to power the planned alumina refinery and will not provide any energy to the surrounding communities.

(a) Truck transporting bauxite on an SMB mining road in Boké.

(b) Trucks kicking up dust on an SMB mining road in Boké.

(c) Mounds of bauxite at SMB headquarters in Boké.

(d) Front gate of SMB operations in Boké.

Figure 6.1.1 SMB’s operations in Guinea:

3.1 SMB’s Environmental and Social Record in Boké, Guinea

In 2022, a Pan-African environmental NGO, Natural Justice, completed a Community Audit of the Boké area to determine the on-the-ground effects of SMB’s mining activities on local communities and their livelihoods. The Community Audit Report notes that the local economic activities impacted by SMB’s bauxite mining include agriculture (rice and mahogany), fishing, salt farming, livestock, trade, and handicrafts, and that these forms of subsistence are under threat due to the bauxite mining activities.Footnote 58 Generally, the report notes the extreme degradation of the natural environment in Boké.Footnote 59 Additionally, according to a report by Human Rights Watch, the required ESIA was not finished and approved before SMB began constructing mining infrastructure such as mining roads and ports.Footnote 60 The same pattern of starting the operation before the ESIA was approved can be found at SMB’s investors’ Simandou iron mine-related infrastructure project, a violation of the Guinean Environmental Code.Footnote 61

One of the main concerns of local communities noted during the community audit is access to safe drinking water. SMB discharges wastewater directly into fields and local waterways, thereby polluting local water sources and making them unsuitable for human domestic use.Footnote 62 Uncontrolled and untreated runoff after periods of rain also contributes to pollution of local waterways, turning streams and rivers the deep red color of bauxite.Footnote 63 Additionally, local communities complain that many of the boreholes and wells drilled by SMB to compensate for the pollution of streams and rivers are not functional. Of the thirty-one boreholes surveyed for the community audit report, only seven were found to be operational at the time of the audit.Footnote 64

Another key environmental complaint of local communities is the copious amounts of dust generated from heavy machinery used for mining operations, including large trucks that travel through communities and on mining roads (Figure 6.1.1). Individuals from Katougouma complain that passing trucks kick up dust that deteriorates the air quality.Footnote 65 Communities also complain that the dust coats their farms and food and has caused respiratory disease among locals.Footnote 66 The Community Audit Report also notes that dust kicked up by trucks coats roadside fruit trees and discusses the need for a dust mitigation program.Footnote 67 Additionally, community members have complained that their land rights have been violated by SMB. Specifically, in Boké, individuals complain that their customary land rights have been ignored and they have not been provided with adequate compensation.Footnote 68

3.2 Civil Society Actions

Despite Xi Jinping’s pledge that China will no longer build coal plants overseas, many Chinese companies have continued with their plans to construct coal-fired power plants.Footnote 69 Thus, bottom-up work led by civil society is necessary to ensure companies comply with both the Chinese government’s and the host country’s laws. A group of Guinean, regional, and international NGOs have been working together to design advocacy strategies to halt the construction of the coal plant in Boké. These NGOs include the Guinean human rights legal nonprofit Les Mêmes Droits pour Tous (MDT), the Association pour le Développement Rural et l’Entraide Mutuelle de Guinée, the US-based environmental legal nonprofit Center for Transnational Environmental Accountability (CTEA, Figure 6.1.2), Natural Justice, and the Ghana-based Advocates for Community Alternatives.

Figure 6.1.2 CTEA Executive Director, Jingjing Zhang, meeting with the Wawayiré village in the Boké prefecture

Even though both the validation of the ESIA of the refinery with the coal plant and the environmental compliance certificate were issued to SMB for the planned refinery and coal plant before Chinese President Xi Jinping announced in September 2021 that China would no longer build coal-fired power plants abroad, nonetheless, SMB failed to change its plan of building a captive coal plant to power the alumina refinery to align the project with China’s policy direction. The consortium of NGOs decided to take action to stop its plan. The main strategies identified include the following: first, applying pressure to SMB to comply with Chinese and Guinean climate policies and commitments, including by writing letters to the Guinean government and the Chinese Embassy in Conakry, media exposure, and participation in UN human rights mechanisms; and second, taking legal action, including access to information requests, Compulsoire,Footnote 70 and administrative litigation,Footnote 71 in Guinea to challenge the approval process for the coal plant.

According to the news on China’s Ministry of Commerce website, other Chinese companies in the Boké and Boffa region, including the State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC), plan to build refineries with captive coal or heavy fuel oil burning plants despite Xi Jinping’s policy prohibiting coal plants.Footnote 72 The NGO consortium is currently working to expand its advocacy efforts to include all planned coal and heavy fuel oil burning plants.

On 13 June 2022, MDT submitted letters to the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Geology and Mines urging them to cancel the plan to build a coal-fired power plant and replace it with a cleaner source of energy. Additionally, on 14 June 2022, one of the authors brought the MDT letters, two ESIAs (SMB and SPIC), and a letter calling for stopping the coal plants to the Chinese Embassy in Conakry (the capital of Guinea). These letters were meant to capitalize on China’s recent pledge not to build new coal-fired power plants abroad while simultaneously setting up potential administrative litigation if the Guinean government refuses to compel SMB to find a cleaner source of energy for the refinery project. In July 2022, both ministries responded favorably to the letters submitted by MDT with the Ministry of Environment stating that the department “will take all necessary steps to examine the concerns of the communities in the SMB mining area.”

In early 2023, MDT and CTEA submitted follow-up letters to both ministries and the Chinese Embassy in Conakry calling for the Guinean government to revoke the environmental compliance certificate and cancel the coal-fired power plant. Additionally, in April 2023, MDT submitted a request to the AGEE asking for a copy of the most recent environmental compliance certificate for SMB’s refinery and coal plant project. MDT met with officials from the AGEE and was told that no environmental compliance certificate had been issued to SMB, which was an excuse to avoid disclosing it. If informal processes to obtain the certificate continue to prove unsuccessful, MDT will submit a Compulsoire or formal information request seeking the certificate.

Crucially, the Compulsoire can be addressed to both the Ministry and the company. The environmental compliance certificate (as discussed in Article 31 of the Guinean Environmental Code) must be renewed each year. The environmental compliance certificate for the SMB’s refinery and coal plant ESIA are set to be renewed in May each year. If the certificate is renewed despite obvious deficiencies with the ESIA, as pointed out in MDT’s letters to the ministries, then the NGO consortium would bring administrative litigation to challenge the decision to renew in the Guinean courts.

On the international stage, CTEA and Natural Justice coauthored and submitted a shadow report to the UN Committee for Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights during its periodic review of China and highlighted Chinese companies’ plans to construct captive coal-fired power plants and made recommendations to the Committee that China has the obligation to oversee Chinese companies operating abroad regarding their human rights impact. As a result of this engagement, the Committee made the following recommendation to China in their concluding observations: “Suspend permissions to construct coal-fired power plants as well as pause ongoing financing construction hereof, including in the State party and abroad,” and “[e]nsure that business entities operating in the State party or those domiciled under the State party’s jurisdiction and those acting abroad, including their sub-suppliers, as well as institutions that provide financing, are held accountable for economic, social and cultural rights violations, paying particular attention to indigenous and peasants’ land rights, environmental impact.”Footnote 73

Because of pressures built by the actions above, in July 2023, an SMB manager had orally promised to abandon its plans to build a coal-fired power plant. It was a victory for communities and civil society organizations. However, SMB is now looking to build a heavy fuel oil plant, which comes with more serious health impacts for the local community, and the legal battle and campaign to stop the fossil fuels power plants will be carried on to a new stage.

4 Conclusion

As SMB forges ahead with its plans to construct a coal-fired power plant, civil society organizations are working tirelessly to ensure that SMB respects the environmental and human rights of local communities. China’s recent commitment not to build any new coal-fired power plants abroad gives civil society an opportunity to pursue advocacy efforts at the international level and exert pressure on SMB to find a cleaner source of energy for its planned refinery. The planned administrative litigation to challenge the renewal of the environmental compliance certificate for SMB’s alumina refinery will be the first of its kind in Guinea and will set the stage for further legal challenges to other companies also planning to construct coal-fired power plants.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

Guinea is a country that has had a tumultuous political history and recently experienced a military coup in 2021. The military junta has yet to hold democratic elections to institute a new leader. Additionally, Guinea has suffered from a weak “rule of law.” The rule of law is defined by the UN as “a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards.”

While Guinea has several environmental statutes by which international corporations are required to adhere, Guinean institutions have failed to enforce these laws and the Guinean judiciary has proven difficult to access by impacted community members and the organizations representing community concerns. What actions do you propose such organizations take to ensure accountability in a country with a weak rule of law? Do you think mobilizing litigation, including administrative litigation or tort litigation, would be more successful in Guinea? Why or why not? What other legal tools are available? And who are the potential defendants? If formal institutions prove inadequate, what extralegal means may be more effective?

The SMB case may shed light on the disconnect, found elsewhere in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, between political rhetoric and the actual conduct of Chinese corporations. What legal avenues are available for affected parties to challenge environmental and human rights violations perpetuated by foreign companies or multinationals? What are SMB’s Chinese investors’ or its parent company’s legal liabilities? Can lawsuits similar to the US’s Alien Tort Claims Act be filed in China? What differentiates the legal liabilities of the parent company and its subsidiaries? Will using the corporation’s or financiers’ grievance mechanisms in China be possible? Are there any climate and biodiversity commitments strong enough to hold Chinese parties accountable to the host country’s laws and international law sources? Are current international environmental laws or international human rights laws adequate to provide legal bases and avenues to redress multinationals’ wrongdoings on the environment and communities?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

As discussed in the case study above, SMB began construction of major mining infrastructure before completing the ESIA. The ESIA process is a crucial first step in any development project. Rushed or incomplete ESIA processes can undermine the entire purpose of evaluating the environmental and social impacts of a project. Additionally, SMB’s ESIA contained several deficiencies, including lacking a climate assessment, reasonable alternatives, and baseline air quality studies. An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a planning tool meant to assess environmental risks of a given project so that decision makers can make fully informed decisions regarding the project.Footnote 74 If project developers begin construction before completing the ESIA, then decisions are made without critical environmental and social information that is crucial to ensuring responsible and sustainable development.

Based on the facts in this case study, what policy tools do you think would be the most effective in ensuring that Chinese companies adhere to their ESIA requirements? Additionally, what are some of the dangers to communities when companies begin construction of large development projects without properly conducting environmental assessments?

Under Guinean law, it is the company proposing the project that is required to conduct ESIAs for proposed projects. However, in other countries, such as the United States, it is the government that is required to conduct such studies.Footnote 75 What are some of the benefits and/or risks of an EIA law that requires the company to conduct ESIAs? Do you think the purpose of environmental assessment laws would be better served if a company or the government conducted the studies?

1 Overview

This case study examines the dispute between Micron Technology, United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), and Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co. Ltd. (“Jinhua”) over the alleged theft of Micron’s trade secrets in integrated circuits (ICs), specifically dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chips. This dispute offers a lens through which to analyze China’s strategic efforts to strengthen its semiconductor industry by overseas investment. It begins by introducing China’s ambitious policy framework aimed at achieving self-reliance in the semiconductor industry, set against the backdrop of geopolitical tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on global IC supply chains. It then turns to the case adjudicated by Taiwanese courts in 2020, where UMC and Jinhua faced allegations of trade secret misappropriation from Micron. Finally, this study compares the different legal and regulatory approaches of Taiwan and the United States in addressing such disputes, highlighting the challenges in regulating global supply chains amidst evolving geopolitical and economic landscapes. Through exploring both the legal complexities and international responses to Chinese outbound investments in critical technologies, this case study delineates the strategic interplay between China’s state-directed industrial goals, international commercial norms, and the pursuit of technological innovation.

2 Introduction

In October 2022, the United States promulgated a series of export controls on China’s access to advanced computing chips and semiconductor manufacturing items designed or produced by American companies. Under the new regulations, restrictions on China’s reach into the global semiconductor value chain are comprehensive, including high-end artificial intelligence (AI) chips, US-made chip design software, and US-built semiconductor manufacturing equipment and components. These controls illustrate the “stranglehold” or “neck choking” (kabozi) challenge that the Chinese authorities have long identified: that Western domination of advanced chip designs and manufacturing can lead to weaponizing its chokepoint positions in the global semiconductor industry to gain leverage over China’s economic and national security interests. From the US perspective, however, this set of new regulations may be read as a direct strategic response to China’s own peculiar approach to the development of its semiconductor industry, which Americans view as highly aggressive.

China makes no secret of its ambition to become a global leader in the integrated circuits industry. Since the early 2010s, the Chinese government has launched several policy initiatives to do so.Footnote 1 Among the most crucial is the State Council’s “2020 IC Notice,”Footnote 2 which replaces most of the country’s previous IC-related policy instructions. Adding muscle to these policy frameworks is the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, also known the “Big Fund.” Created as a government guidance fund, the fund is designed to assist China in realizing its aim of becoming self-reliant in the semiconductor sector, aligned with the broader objectives of the “Made in China 2025” plan.Footnote 3

While China’s drive to develop its semiconductor industry may seem like part of a global trend,Footnote 4 the country’s circumstances are notably distinct due to geopolitics and the aftereffects of COVID-19. The pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in the international IC supply chain, leading to disruptions and bottlenecks that wreaked havoc across multiple industries. The crisis underscored the perils of depending on a handful of key semiconductor suppliers, especially when they are concentrated in specific geographic regions. This awareness has prompted many countries, including China, to reconsider their reliance on foreign chip suppliers and explore ways to bolster domestic production and research. For China, however, the situation is compounded by additional layers of geopolitical tensions, notably the sanctions imposed by the United States. These sanctions have not only restricted China’s access to cutting-edge semiconductor technology but also accelerated its drive for self-sufficiency in IC production. The confluence of geopolitics and pandemic-induced supply chain issues has made China’s semiconductor landscape unique, heightening the urgent need for the country to develop a resilient and independent chip industry.

China’s official policy documents thus reveal a pivot toward semiconductor self-reliance that diverges from the current model of global interdependencies. These policies explicitly advocate for a self-sufficient and enclosed semiconductor production system within China, positioning the country as the epicenter of global semiconductor production. This is a striking departure from the highly globalized structure of current IC supply chains and represents an ambitious goal. Contrasting with the approach for deeper global integration, Beijing’s leadership perceives the status quo as a national security vulnerability. They prioritize security over efficiency or global cooperation, viewing interdependence as a threat that exposes the country to potential supply chain disruptions, notably from the United States and its allies.

As prescribed in these policy instructions, measures specified or encouraged by the state have been wide-ranging. One key measure is providing a set of tiered tax incentives such as exemptions or reductions in enterprise income tax or value-added tax. IC companies that produce chips with a line width of smaller than 28 nanometers and that have operated for more than fifteen years, for instance, will be exempt from corporate income tax for the first ten years of operation (Article 1.1, 2020 IC Notice). IC companies that have been in operation for less than fifteen years, starting from the year they become profitable, will be exempt from corporate income tax for the first and second years, and for the third to fifth years their corporate income tax will be levied at half of the statutory rate of 25% (Article 1.2, 2020 IC Notice). Other measures include inducement subsidies, concessional loans, mergers and acquisitions (M&As), and talent recruitment.

There is more to the worries about China’s ambition in the semiconductor industry than meets the eye. The source of concerns stems primarily from its highly strategic, often strong-armed approach to technological advancement, which is at odds with the liberal ideal of market competition and international commercial norms. To accelerate the self-sufficiency of its chip industry, for example, China’s FDI incentive scheme often encourages foreign firms to form joint ventures and share their technology with local partners in exchange for access to the Chinese semiconductor market.Footnote 5 This same tactic of technology transfer is also seen in China’s overseas investment in the semiconductor industry, particularly through M&As that permit the repatriation of more advanced know-how.Footnote 6 However, alongside these more formal and sanctioned strategies, some Chinese companies have been accused of adopting more aggressive, under-the-table tactics such as talent acquisitions and the misappropriation of trade secrets or other forms of intellectual property. Owing to the controversial nature of these practices, they frequently result in legal challenges, criminal charges, and regulatory crackdowns on Chinese investment in the host state’s sensitive areas.

One high-profile example that encapsulates these issues is the criminal case involving trade secrets between Micron, UMC, and Jinhua, which was adjudicated by Taiwanese courts in 2020.

3 The Case

3.1 Court Case: UMC and Jinhua

China’s ambition to lead in the semiconductor industry is intrinsically tied to its broader strategic objective of becoming a global powerhouse in AI. Both sectors are interdependent: Semiconductors serve as the foundational technology for AI-enabled applications. Take, for example, DRAMs. These chips are staples in everyday electronic devices like smartphones and computers, but their role has become increasingly important due to the data-intensive nature of modern AI applications. DRAM chips enable quick access to vast amounts of data, a necessity for the real-time processing performed by AI algorithms.

Despite the government’s generous funding for the semiconductor industry, Chinese firms have yet to break into the DRAM market. In terms of market share, Samsung and SK Hynix in South Korea continue to dominate the industry, followed by Micron in the United States. This monopolization is largely due to the highly competitive nature of the DRAM industry, which requires not just massive capital investment for manufacturing facilities but also specialized expertise. All these factors make it difficult for latecomers to challenge the dominance of the key players. Nonetheless, this has not stopped some key Chinese companies from trying and Micron was one such target.

Founded in 1978, Micron is a multinational corporation specializing in designing and manufacturing not just DRAM but also other types of memory chips such as NAND flash memory and solid-state drives. Headquartered in Boise, Idaho, in the United States, Micron also operates many production facilities in the Asia-Pacific region. Tsinghua Unigroup’s US$23 billion acquisition offer in 2015 was the first attempt to approach Micron.Footnote 7 Micron did not think this deal was realistic as it assumed that the US regulator would not approve the transaction due to national security concerns.Footnote 8 Hence, the deal did not go forward.

One year later, Micron was targeted by another Chinese company, Jinhua, a Fujian-based DRAM chipmaker. Unlike Tsinghua Unigroup’s straightforward takeover bid, Jinhua took a more circuitous route. Jinhua entered into a licensing agreement with UMC, a major Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer. UMC had just recruited the president of Micron’s Taiwan branch, thereby gaining valuable insights into DRAM production. According to the Taichung District Court,Footnote 9 in January 2016 UMC struck a deal with Jinhua that provided UMC with US$700 million in exchange for developing and providing knowledge transfer about DRAM production processes. Up to this point, the deal appeared to be legally sound. However, two years later, in 2018, UMC and three individuals involved in the collaboration – Jianting Ho, Yongming Wang, and Letian Rong – were charged with criminal violations of Taiwan’s Trade Secret Law.

In 2020, the Taichung District Court found them guilty of infringing Micron’s trade secrets. UMC was ordered to pay a fine of NT$100 million.Footnote 10 Ho, Wang, and Rong were sentenced to five years and six months, four years and six months, and six years and six months, respectively.Footnote 11 The decision was appealed to the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court (IPCC).Footnote 12 In January 2022, the IPCC reversed the district court’s decision.Footnote 13 UMC’s fine was reduced to NT$20 million. Ho’s sentence was reduced to one year, whereas Wang’s was reduced to only six months. Rong was acquitted of all charges. The IPCC’s ruling against UMC is final. The charges against individuals were appealed by prosecutors to Taiwan’s Supreme Court. In August 2022, the Supreme Court reversed the decision and remanded the case back to the IPCC for further proceedings. As of September 2023, the criminal charges against Ho, Wang, and Rong are still pending in the IPCC.

According to the information presented in these decisions, the licensing collaboration between UMC and Jinhua raised some questions about potential irregularities, particularly given UMC’s area of expertise. UMC is a major semiconductor manufacturer focused primarily on the design and production of logic chips, not memory chips like DRAM. This specialization made the licensing arrangement with Jinhua, a DRAM chipmaker, somewhat unusual and prompted scrutiny.

To further contextualize, in 2015 UMC recruited Stephen Chen, who had previously served as the president of Micron Memory Taiwan Co., Ltd. (hereinafter, “MMT”). Chen was tasked with leading UMC’s New Business Development unit, established in January 2016 specifically to finalize a DRAM licensing deal with Jinhua. Chen also recruited two former employees from MMT, Ho and Wang, to join UMC’s new unit.

Both Ho and Wang had worked at MMT for several years, during which they had gained access to Micron’s confidential data and trade secrets related to memory chips. The fact that these individuals, who had access to sensitive Micron information, were now involved in a DRAM deal between UMC and Jinhua raises questions about the true intent behind the licensing arrangement.

Ho was accused of reproducing and using the trade secrets that he had acquired during his employment at MMT. Wang was introduced to UMC by Ho and was offered a salary that was equal to his position at MMT, plus an additional bonus upon signing another employment contract with Jinhua and working in Mainland China. Wang resigned from MMT on 26 April 2016 and started at UMC two days later. However, before leaving MMT, he downloaded and copied the company’s trade secrets onto a USB drive and uploaded them to his Google Drive. All these actions took place between 16 April and 23 April 2016 while Wang was still employed at MMT. He then used the data to help UMC develop DRAM products.Footnote 14 As the court shows, the licensing collaboration between UMC and Jinhua involved two stages: initially conducting research and development (R&D) in Taiwan and then transferring the technology to Jinhua.Footnote 15 In the scenario presented in the court decisions, talent acquisition and trade secret theft were the major measures adopted to achieve the licensing agreement’s objectives.

3.2 Regulatory Analysis

Currently, the key legislation that governs China’s investment in Taiwan is the Act Governing Relations between Peoples of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (hereinafter, the “Cross-Straits People Relations Act”).Footnote 16 Pursuant to Article 40-1 of the Act, Mainland Area profit-seeking enterprises, as well as their investments in other territories, are prohibited from conducting any business activities within the Taiwan Area without prior authorization from the competent authorities and the requisite establishment of a local branch or liaison office. Similarly, Article 73 mandates that individuals, juristic persons, organizations, or other institutions from the Mainland Area, along with any companies they invest in within other territories, may not partake in investment activities within the Taiwan Area without explicit permission from the competent authorities.

As the court decisions reveal, the licensing agreement between UMC and Jinhua received regulatory approval from the Investment Commission of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEAIC) in Taiwan,Footnote 17 making it legitimate under current Taiwanese law. However, if Jinhua’s objective was merely to develop or acquire expertise related to DRAM production, this collaboration seems inefficient, especially considering that UMC does not specialize in memory chips. This raises the possibility that Jinhua’s strategy may have been designed to circumvent Taiwanese laws restricting the recruitment of talent from Taiwan, as prohibited in the Cross-Straits People Relations Act.

Article 34 of the Cross-Straits People Relations Act contains strict restrictions on job recruitment information for positions in Mainland China. According to this article, job positions in Mainland China cannot be advertised in Taiwan without permission. Advertisers or human resources agencies who violate this rule are subject to Article 89, Paragraph 1 of the Act. It stipulates that any person who entrusts to another, is entrusted, or acts on their own to engage in advertisement broadcast or publication, or any other promotion activity in the Taiwan Area for any goods, service, or other item of the Mainland Area other than those prescribed in Paragraph 1 of Article 34, or violates Paragraph 2 of Article 34 or the mandatory or prohibitive provisions of the rules governing the management prescribed in accordance with Paragraph 4 of Article 34, shall be punished with an administrative fine of not less than NT$100,000 and no more than NT$500,000.

In more practical terms, any company registered in Taiwan, foreign company, or foreign company branch office or representative office that is registered or approved to operate in Taiwan, is not allowed to post job advertisements that list Mainland China as the workplace. This means that advertisements for positions in Mainland China cannot be published on job search websites or any other platform, including the company’s official website or social media platforms in Taiwan. According to the Regulations for Advertising Goods, Labor and General Services of the Mainland Area in the Taiwan Area, a specific exception exists for posting job advertisements. If a domestic company has received approval from MOEAIC to invest in Mainland China and establish a Taiwan-funded enterprise, it is permitted to list Mainland China as the workplace in job advertisements (Article 6, Paragraph 5).

By entering into a technology transfer agreement with a Taiwan-based chip company like UMC, neither Jinhua nor UMC needed to establish their own R&D capacity in Mainland China. Such a licensing collaboration is not unusual assuming no criminal activities related to trade secret theft are involved. However, as illustrated in a number of court decisions, talent poaching frequently leads to misappropriation of trade secrets and intellectual property in order to facilitate R&D outputs. As Wang himself revealed during the investigation, this behavior is largely motivated by financial gain: “I only have my eyes set on the output, making money, and then retiring.”Footnote 18

Under Taiwan’s Trade Secret Act, trade secret theft is a serious offense. Promulgated in 1996, the Act initially did not have a criminal clause to regulate misappropriation of trade secrets. It was not until 2013 that it criminalized such wrongdoing by adopting a dual-track model. Article 13-1 specifies the penalties for committing acts related to trade secret theft, embezzlement, fraud, and unauthorized reproduction, usage, or disclosure, and outlines the fines that may be imposed in addition to imprisonment. Under Article 13-1, the maximum penalty for trade secret misappropriation is five years’ imprisonment in addition to a fine of between NT$1 million and NT$10 million.

Article 13-2 adds additional penalties for committing these crimes with the intention of using the trade secret in foreign jurisdictions, including Mainland China, Hong Kong, or Macau, and increases the potential fines that may be imposed for such offenses. Under Article 13-2, the penalty for committing such an offense with the intention of using the trade secret in foreign jurisdictions is imprisonment of between one and ten years, in addition to a fine of between NT$3 million and NT$50 million. The penalties outlined in Article 13-2 are generally considered to be harsher than those in Article 13-1, which may serve as a stronger deterrent against trade secret misappropriation with the intention of using the information in foreign jurisdictions.

The issue at the heart of the UMC-Jinhua case pertains to the potential violation of Article 13-2 of Taiwan’s Trade Secret Act by the three individuals in question, namely Ho, Wang, and Rong. The Taichung District Court concluded that they had indeed violated this provision, while the IPCC reversed this decision on appeal, finding that the defendants did not meet the legal standard required for a conviction under Article 13-2. However, the decision was later remanded by Taiwan’s Supreme Court, which required the IPCC to consider the following evidence and issues: Wang’s confession regarding his knowledge of the UMC-Jinhua licensing collaboration; Ho’s statement regarding his employment contract signed with Jinhua during October and November 2016; a witness’s statement that UMC planned to arrange for employees involved in the collaboration to open bank accounts in Mainland China with incentive bonuses being wired to their accounts once product development was complete; Wang’s communication with his friends where he stated “Conducting R&D in Taiwan and transferring the technology to Mainland”; and UMC’s application to MOEAIC for the approval of the UMC-Jinhua licensing collaboration.Footnote 19 The Supreme Court indicated that the evidence listed above seemed to suggest that the three individuals had the intention of using Micron’s trade secrets in Mainland China.

3.3 International Responses

The UMC-Jinhua licensing collaboration has faced legal challenges not only in Taiwan but also in the United States. In September 2018, the US government indicted UMC and Jinhua for conspiracy to commit economic espionage and to steal trade secrets from Micron.Footnote 20 The following month, the US Department of Commerce added Jinhua to its export restriction list, prohibiting the company from purchasing components, software, and technology goods from US firms.Footnote 21 In 2020, UMC pleaded guilty to a single count of criminal trade secret theft and offered to pay a US$60 million fine. In November 2021, the US Department of Justice dismissed other allegations against UMC, including conspiracy to commit economic espionage, and UMC and Micron agreed to a global settlement.Footnote 22 Jinhua, on the other hand, denied any wrongdoing related to the allegations. However, the consequences for Jinhua were severe. In the wake of the US export restrictions, Jinhua was forced to cease production of memory chips within a few months, and it did not resume operations until 2022 when it received assistance from Huawei and shifted its focus to manufacturing logic chips.Footnote 23

It is worth noting that the US Department of Justice indicted Jinhua as a major defendant largely due to its technology cooperation agreement with UMC that took place in or around January 2016. The US government’s indictment against Jinhua reflects its discourse that China engages in unfair and illegal practices to acquire technology, and as a Chinese state-owned enterprise, Jinhua is particularly vulnerable to such a perception. The statement released by the US Department of Justice implied just that:

The theft of intellectual property on a continuing basis by nation-state actors is an even more damaging affront to the rule of law. We in the Northern District of California, one of the world’s great centers of intellectual property development, will continue to lead the fight to protect U.S. innovation from criminal misappropriation, whether motivated by personal greed or national economic ambition.Footnote 24

Compared to the legal and political backlash in the United States against the UMC-Jinhua licensing collaboration, Taiwan’s justice system has taken a more restrained approach. Jinhua has never been considered a defendant in the case and the collaboration was not seen as Jinhua’s involvement in a conspiracy to commit economic espionage or steal trade secrets. The court decisions in Taiwan have only implicated UMC and its three employees, Ho, Wang, and Rong, in the theft of trade secrets. Jinhua’s role in facilitating the theft of Micron’s trade secrets was not confirmed in the court decisions.

In February 2024, Jinhua was cleared of charges related to economic espionage and other criminal allegations in the United States.Footnote 25 Judge Chesney ruled that the evidence presented by US prosecutors did not sufficiently demonstrate that Jinhua, with state support, had unlawfully acquired confidential information from Micron.Footnote 26 Nonetheless, this case, initiated in 2018, has garnered considerable attention, spotlighting concerns over China’s pursuit of semiconductor self-sufficiency, which includes acquiring technologies from abroad.Footnote 27 Key stakeholders in the global IC supply chain have closely monitored the UMC-Jinhua conflict.

4 Conclusion

Semiconductors have emerged as critical components within contemporary geopolitics, holding significant implications for national security due to their incorporation in both civilian and military applications. Recognizing the strategic imperative of these technologies, China’s pursuit of semiconductor development and acquisition is a strategic initiative aimed at enhancing its technological autonomy and may influence the reorientation of the global supply chain to a more China-centric model. This move presents a potential shift from the established supply chain dynamics, traditionally influenced by US-centric alliances.

Taiwan’s leading role in manufacturing chips places it at the heart of these geopolitical tensions, particularly considering its political relationship with China. This environment amplifies the sensitivity of semiconductor technology as a point of international contention, where economic ambitions intersect with national security priorities. The UMC-Jinhua case illustrates the challenges in differentiating between sanctioned technological collaboration and the misappropriation of trade secrets. The incident reveals how an endorsed collaboration can potentially lead to unlawful activities, highlighting the importance of thorough oversight in cross-border technological partnerships. While this case involves China, it exemplifies a global concern where informal business engagements require scrutiny to align with the host state’s legal and regulatory frameworks.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

5.1.1 Law and Politics

The legal dispute involving Micron, UMC, and Jinhua centered on accusations of unauthorized use of Micron’s trade secrets. Taiwanese courts primarily assessed the conduct of UMC and certain employees, while the US Department of Justice extended its scrutiny to Jinhua, indicting the company as a major defendant.

The divergent approaches by Taiwanese and US legal systems may stem from their distinct legal frameworks and enforcement priorities. Taiwan’s focus on individual and corporate conduct within its jurisdiction aligns with its legal traditions, emphasizing direct involvement and evidence of misappropriation. The United States, conversely, may have broader geopolitical and economic considerations, employing legal instruments as part of its strategic enforcement against perceived threats to its technological leadership.

The indictment of Jinhua by the US government could be interpreted within the larger context of allegations against China’s methods of acquiring advanced technology. This framing raises critical legal questions about the international standards of corporate behavior, the enforcement of intellectual property rights, and the nexus between government actions and corporate strategies. The UMC-Jinhua case, initially sanctioned by Taiwanese authorities, now invites scrutiny under the lens of these broader geopolitical conflicts.

1. What legal principles underpin the different approaches taken by Taiwan and the United States, and how do these principles manifest in cross-border enforcement and extraterritorial application of laws?

2. How do these legal actions reflect and impact the regulatory challenges inherent in managing international supply chains, particularly in the high-tech sector?

3. Does the UMC-Jinhua case serve as a microcosm of the broader geopolitical struggle between the world’s two largest economies, the United States and China? Why or why not?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

5.2.1 Economic Espionage and Policymaking

In the UMC case heard by Taiwanese courts, Jinhua was not identified as the primary agent of economic espionage; the focus was rather on UMC and certain employees. The absence of direct evidence in court records tying Jinhua to espionage directives suggests that worries about economic espionage are broader and not necessarily confined to the actions or policies of any one nation.Footnote 28 Therefore, it is essential to approach each case on its merits without preconceived notions tied to the national origin of the entities. Many countries are currently challenged with promoting innovation and international cooperation while simultaneously protecting intellectual property rights and ensuring national security. The entanglement of these conflicting goals presents a need for policy considerations beyond the trend of reducing reliance on foreign entities, commonly referred to as “decoupling.” Further questions to be discussed include:

1. What legal and regulatory measures can be implemented to impartially address economic espionage, ensuring equal treatment across different national contexts?

2. How might nations tactically support innovation and uphold intellectual property and security without resorting to complete disengagement from international collaboration?

3. What collaborative efforts between the public and private sectors are necessary to mitigate the risks of economic espionage in critical industries like semiconductor manufacturing, without impeding the flow of trade and technological progress?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

5.3.1 Business Strategies and the US-China Tech War

Amid escalating US-China tensions in technology, the outcomes of the UMC-Jinhua case are likely to shape global tech industry practices going forward. US regulatory actions, including the addition of certain Chinese entities to the Entity List and the application of Export Administration Regulations (EAR), have increased scrutiny of international transactions involving sensitive technologies.Footnote 29 Consequently, companies worldwide, including those in Taiwan with core technology specializations, are assessing their international partnerships.

In addressing these developments, companies are advised to enhance their strategies for intellectual property protection to align with current international trade regulations. This may include evaluating current alliances, especially those potentially affected by US-China technological disputes and considering engagement with emerging markets for diversification. Key strategic measures could involve:

strengthening internal protocols to secure intellectual property, aligning them with international best practices, and engaging in regular audits;

enhancing transparency and communication channels with international partners to foster trust and align business strategies with the global regulatory environment; and

exploring diversification in customer bases and supply chains, to reduce reliance on a particular market, thereby mitigating risks associated with geopolitical uncertainties.

From a business strategic perspective, consider the following questions for further discussions:

1. In what ways can firms recalibrate their international collaboration models to ensure trust and compliance amidst stringent regulations like the US Entity List and EAR restrictions?

2. What strategic shifts should companies undertake to diversify their market engagement and supply chain dependencies in the face of escalating geopolitical tensions in technology?

3. What specific measures should tech companies adopt to bolster intellectual property protection and foster better communication with international partners to build trust and minimize risks associated with the current US-China frictions over technological supremacy?

1 Overview

Over the years, the economic relationship between China and African states has continued to grow and this is evident in the volume of Chinese investments in Africa.Footnote 1 In the wake of these investments, China and African states have signed bilateral investment treaties (BITs), which aim to promote the development of host states and protect foreign investments from one contracting state in the territory of the other contracting state, thereby stimulating foreign investments by reducing political risk. BITs are unique in character in that they provide substantive protections to foreign investors and a basis for claims by an individual or company against a host state on grounds that such substantive protections have been breached by the host state. In order to avoid the need to turn to the national courts in the host state for a judicial remedy, BITs usually contain an arbitration clause submitting disputes to a neutral arbitration tribunal. This case study demonstrates one such instance where, in a first-of-its-kind case, a Chinese investor sued Nigeria, an African host state, for breach of its treaty obligations under the China-Nigeria BIT 2001 (“China-Nigeria BIT”),Footnote 2 and throws light on how BITs can be used in the protection of Chinese outbound investments, including in Africa.

2 Introduction

This case study discusses an investment dispute between a Chinese company, Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Company Limited (“Zhongshan”), and the Federal Republic of Nigeria (“Nigeria”) under the China-Nigeria BIT that resulted in an arbitration award dated 26 March 2021 (the “Award”).Footnote 3 This is the first investment treaty arbitration won by an investor from Mainland China against a sovereign state in Africa. It is also the first arbitration Award ever made against Nigeria in an investment treaty dispute. The place of arbitration was London, United Kingdom, but the arbitration proceedings were held virtually due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. The hearing was conducted under the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).Footnote 4

This case study sheds light on Chinese corporate behavior, Chinese companies’ approaches to mitigating investment risks in international business, their use of the investment treaty arbitration regime,Footnote 5 and, ultimately, Chinese investment behavior at large. The case study demonstrates how Chinese companies navigate policy and regulatory challenges in local markets in their host states. The case of Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria is a good example of the use of an investment treaty by a Chinese investor to protect its investment against the unbridled use of power by a sovereign host state, in this case Nigeria. In terms of data and methodology, the case study draws on primary source documents (see Table 6.3.1) and a semi-structured interview with one of the lawyers who indirectly participated in the arbitration proceedings. The interview revealed that this case study should reassure other Chinese companies that recourse to investment treaty arbitration may increase protection for their foreign investment. This case, therefore, serves as a valuable lens through which to examine Chinese investments in Nigeria, and on the African continent at large.

Table 6.3.1 List of primary documents

| Primary documents | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Annual flow of foreign direct investments from China to Nigeria between 2011 and 2021 |

| 2. | Map of Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone |

| 3. | Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments (China-Nigeria BIT), 2001 |

| 4. | Framework Agreement between Zhuhai and Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone (“OGFTZ Company”) on the Establishment of Fucheng Industrial Park in Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone, 2010 |

| 5. | Joint Venture Agreement between Ogun State, Zhongfu and Zenith Global Merchant Limited for the Development, Management, and Operation of the Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone, 2013 |

| 6. | Framework Agreement between Ogun State, Zhongfu and Zenith Global Merchant Limited, and Xi’an Ogun Construction and Development Limited Company, 2016 |

| 7. | Final Arbitral Award dated 26 March 2021 in Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria |

| 8. | Order of Seizure of Nigeria’s Bombardier Aircraft Issued by the Superior Court of Quebec, Canada, 25 January 2023 |

| 9. | Entrustment of Equity Management Agreement between Guangdong Xinguang International Group Co., Ltd., and Zhuhai Zhongfu Industrial Group Co., Ltd., 2012 |

| 10. | Petition Filed by Zhongshan to Recognize and Enforce Foreign Arbitral Award Between Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd. v. The Federal Republic of Nigeria before the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (Case 1:22-cv-00170), Civil Action, 25 January 2022 |

| 11. | An Order of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia Recognizing the Arbitral Award Between Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co. Ltd., v. Federal Republic of Nigeria [Civil Action No. 22-170 (BAH)], 26 January 2023 |

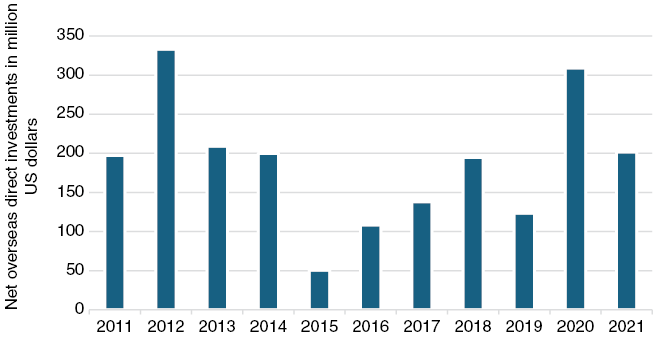

As background to the China–Nigeria investment relationship, China’s outbound investments across the world, including in African countries, have continued to grow massively since 2005, now exceeding US$2.3 trillion.Footnote 6 In Africa and Nigeria specifically, Chinese investments are rooted in various institutional and policy frameworks adopted by China and African countries. Since the beginning of the century, Chinese state-owned enterprises and private companies have increasingly invested in Nigeria under China’s investment policy framework known as the “Going Out” strategy.Footnote 7 The result has been an influx of Chinese businesses into the Nigerian market. Figure 6.3.1 shows the volume of foreign direct investment from China to Nigeria between 2011 and 2021. As the data shows, about US$201.67 million’s worth of direct investments from China were made in Nigeria in 2021. Chinese investment in Nigeria’s manufacturing sector can be traced back to as early as the 1960s when private Chinese companies, such as the Lee Group of Companies and Western Metal Products Company, made early strides in Nigeria.Footnote 8

Figure 6.3.1 Annual flow of foreign direct investments from China to Nigeria between 2011 and 2021 (million US$)

In addition to the “Going Out” strategy, the first Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit was held in Beijing in November 2006 where a new type of strategic partnership between China and African states was declared.Footnote 9 The African continent has great potential to attract Chinese investors, particularly given that Africa features natural resources and emerging economies.Footnote 10 At the Summit, the Chinese and African governments agreed to establish special economic zones, among other things, to deepen economic and trade relations between China and African states.Footnote 11 In fact, the Ogun Guangdong Free Trade Zone (the “Zone”),Footnote 12 which is the location of the Chinese investment that resulted in the investment arbitration that this case study discusses, was established in 2009 and exemplifies the implementation of one of the declarations of the 2006 FOCAC Summit and the Sino-Nigeria investment partnership. The Zone is located in Ogun State in Southwest Nigeria,Footnote 13 and 50 km from Lagos as shown in Figure 6.3.2.Footnote 14 The Zone covers an area of 2,000 ha of land owned by the Ogun State government.Footnote 15 For Nigeria, the establishment of the Zone is economically significant as the objective is to support the country’s plan to diversify its economy away from sole reliance on petroleum. As of September 2023, there are 56 companies operating in the Zone and 600 Chinese employees.Footnote 16 The Zone is also seen by Chinese authorities as a necessary component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) adopted by the Chinese government in 2013.

Figure 6.3.2 Map of Ogun Guangdong free trade zone

As a general observation, cross-border investments by Chinese companies in emerging markets are sometimes prone to risks, which include adverse or illegitimate actions from the host state. To guard against the attendant risks, China signs investment treaties with foreign states. As of the end of 2023, the Chinese government has 107 BITs with foreign states (including Nigeria) that are in force and 16 BITs that have been signed but are not yet in force.Footnote 17 These BITs primarily aim to protect Chinese investors and their investments in the host state, while host states hope that such investments will foster overall socioeconomic development in their country. Therefore, the BITs that China has signed and are in force typically provide substantial protection and guarantees for qualifying Chinese investments abroad. In these BITs, Nigeria, for instance, guarantees Chinese investors that their investments shall be treated in a fair and equitable manner and shall not be expropriated without appropriate compensation. In addition, the BITs, as this case study will demonstrate, allow Chinese investors to institute claims against host states before an arbitral tribunal if their investments are treated in a manner that is contrary to the terms of the relevant BIT, without the need to exclusively rely on the national courts of the host states. In recent times, Chinese business enterprises have demonstrated their willingness to resort to arbitration to resolve investment disputes between them and host states for the protection of their investments abroad. According to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) case database, as of 10 September 2023, there have been ten ICSID cases filed by Chinese investors as claimants, of which five cases are still in progress.Footnote 18