Introduction

Negative interactions between carnivores and people, often referred to as human–carnivore conflict, are a leading cause of carnivore decline globally (Ripple et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2014; Fisher, Reference Fishbein and Ajzen2016). Such conflict may arise when the activities of carnivores affect the livelihoods or safety of communities, which can result in persecution of carnivores (Inskip & Zimmermann, Reference Hemson, Maclennan, Mills, Johnson and Macdonald2009). It is exacerbated when local people perceive that wildlife protection is prioritized over their own needs, or when authorities lack the ability to manage conflict appropriately (Madden, Reference Lindsey, Du Toit and Mills2004).

To minimize human–carnivore conflict, the conservation of large carnivores has in the past primarily depended on the creation of protected areas (Packer et al., Reference Ng and Cribbie2013). However, large predators range over vast areas and often use adjacent unprotected landscapes, which are typically shared with people (Carter & Linnell, Reference Carter and Linnell2016). Such shared landscapes now represent a substantial proportion of the remaining ranges of most large carnivore species (Di Minin et al., Reference Di Minin, Slotow, Hunter, Montesino Pouzols, Toivonen and Verburg2016), underscoring the need for research on the interface between human and wildlife communities. Livestock-rearing communities are affected by depredation, particularly within and around protected areas (Ripple et al., Reference Redpath, Young, Evely, Adams, Sutherland and Whitehouse2014). This can result in financial hardship, reduced emotional well-being, and increased time spent guarding livestock that could have otherwise been spent improving livelihoods (Rostro-García et al., Reference Romañach, Lindsey and Woodroffe2016).

Previous studies on human–wildlife interactions have recognized the complexity of social-ecological systems and highlighted the need for an interdisciplinary approach integrating ecological, economic and social contexts (Dickman, Reference Dickman2010; Redpath et al., Reference Core Team2013). Examining the attitudes of communities living near wildlife areas is important for informing effective conflict mitigation. A better understanding of the factors that influence community attitudes towards carnivores, particularly those that negatively affect attitudes towards wildlife, is needed to achieve human–carnivore coexistence and reduce negative outcomes for both people and carnivores.

Broad strategies to improve human–wildlife coexistence include community-based natural resource management (Fabricius, Reference Fabricius, Fabricius, Koch, Magome and Turner2004) and integrated conservation and development projects (Alpert, Reference Alpert1996), both of which aim to provide tangible benefits of conservation to local communities. Other human–carnivore coexistence strategies include compensation schemes (Dickman et al., Reference Dickman, Macdonald and Macdonald2011) and community-based livestock insurance programmes (Mishra et al., Reference Madden2003). The effectiveness of these strategies depends on local contexts, attitudes and institutional capacities.

Key determinants of attitudes vary depending on political, social, economic, cultural and geographical factors (Madden, Reference Lindsey, Du Toit and Mills2004). However, previous studies point to common variables underlying conflict, such as previous livestock losses, livestock demographics, husbandry methods, socio-demographic and socio-economic factors, knowledge of wildlife behaviour, and prior experience with raising livestock and encountering carnivores (Zimmermann et al., Reference van Griethuijsen, van Eijck, Haste, den Brok, Skinner and Mansour2005; Kansky & Knight, Reference Inskip and Zimmermann2014; Thorn et al., Reference Störmer, Weaver, Stuart-Hill, Diggle and Naidoo2015; Störmer et al., Reference Stein, Athreya, Gerngross, Balme, Henschel and Karanth2019). Consideration of these variables is essential to ensure carnivore management policies are locally appropriate and minimize negative social impacts. Ultimately, approaches intended to facilitate coexistence need to consider social as well as ecological aspects, especially in tropical contexts, where trade-offs often occur between economic development and biodiversity conservation (Laurance et al., Reference Kittle, Watson, Kumara and Sanjeewani2012).

Sri Lanka is a global biodiversity hotspot with high rates of endemism. The country relies economically on its biodiversity for tourism, but this diversity is threatened by a high human population density, with the majority of people living in rural areas (Bawa et al., Reference Bawa, Das, Krishnaswamy, Karanth, Kumar and Rao2007). The Sri Lankan leopard Panthera pardus kotiya is an endemic subspecies of leopard that is increasingly threatened by habitat loss resulting from the expansion of cattle (dairy) farming (Vernooij et al., Reference Uduman2015). This leopard subspecies is currently categorized as Vulnerable (Kittle & Watson, Reference Kittle and Watson2020) on the IUCN Red List; at the time of our study it was categorized as Endangered (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Athreya, Gerngross, Balme, Henschel and Karanth2020) and was presented as such.

The Sri Lankan leopard is the island's apex predator and a potential keystone species (Kittle et al., Reference Kansky and Knight2018). It holds high economic value, given that wildlife park visits are the third highest source of public sector tourism revenue (SLTDA, Reference Sekhar2017). Maintaining viable leopard populations is thus important because of the species’ ecological and economic role, as well as its intrinsic value. When leopards prey on livestock, even if losses are few in absolute numbers, they can represent a significant challenge for economically vulnerable rural communities whose livelihoods depend on livestock farming (Dickman, Reference Dickman2010). Sustained economic hardship may lead to the retaliatory killing of leopards, which does occur in Sri Lanka, usually by poisoning depredated livestock carcasses (Fernando, Reference Fernando2016; Uduman, Reference Uduman2020). However, quantitative data on livestock depredation and its impact on people and leopard populations are lacking.

Using quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews, we examine attitudes towards leopards, and identify their determinants, in two rural communities with different approaches to cattle rearing. Based on these insights, we identify potential strategies, grounded in the local context, that could address factors underlying negative attitudes towards leopards, to improve human–leopard coexistence.

Study area

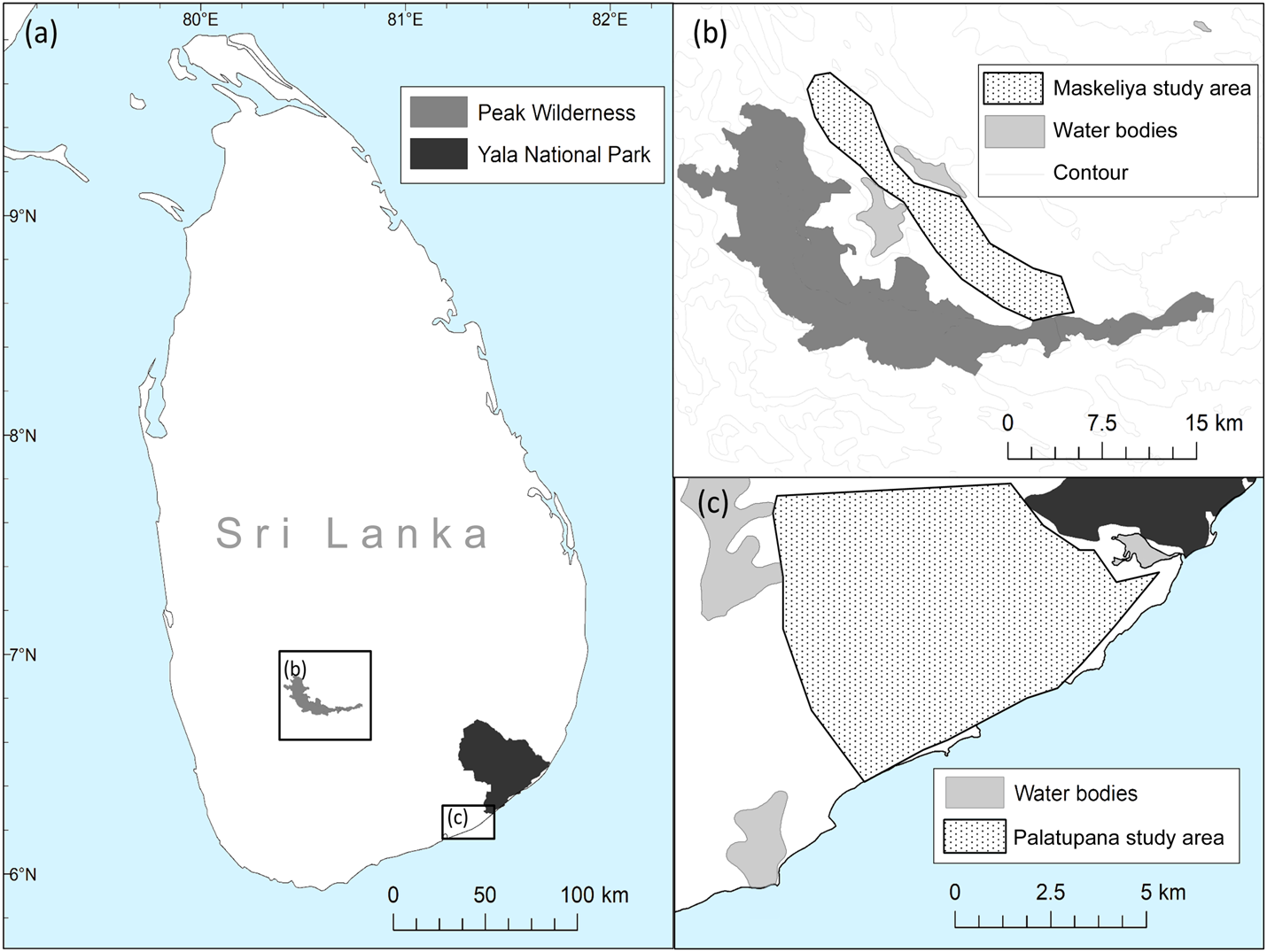

We selected two study sites where cattle are reared in landscapes inhabited by leopards (Fig. 1), but that differ in socio-demographics and cattle farming history. The first site, Palatupana, is in the south-eastern coastal region of Hambantota District, near Yala National Park, with one of the highest leopard densities globally (Kittle et al., Reference Kittle, Watson, Cushman and Macdonald2017). Palatupana is adjacent to the south-western boundary of the Park and is characterized by thorny scrub forest. Yala National Park is the most visited national park in Sri Lanka, generating c. LKR 670 million (c. USD 3.68 million) in annual revenue (SLTDA, Reference Sekhar2017). An electric fence separates the Park from the surrounding area, but wildlife including elephants Elephas maximus, Sri Lankan axis deer Axis axis ceylonensis, wild boar Sus scrofa and primates such as the tufted grey langur Semnopithecus priam move between the Park and adjacent areas despite this fence. Luxury hotels in the area advertise the frequent wildlife presence around their properties to attract tourists. The primary occupation of the local community is cattle rearing, with cattle grazing in areas inhabited by wildlife, including leopards, some of which may be transient and dispersing individuals. Incidents of cattle depredation by leopards are occasionally reported by cattle owners and recorded by the Sri Lankan Department of Wildlife Conservation.

Fig. 1 Sri Lanka (a), with study sites in Maskeliya (b) and Palatupana (c), where we conducted surveys and interviews with cattle owners.

The second site, Maskeliya, is within the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the island's central wet zone. This region is dominated by large-scale tea plantations whose owners are increasingly permitting estate workers to rear cattle. It has a high human population density and is characterized by a landscape mosaic of tea cultivation, degraded secondary forest, less-disturbed forest patches and human settlements. Leopards inhabit forest patches at higher altitudes and use tea estates as movement corridors (Kittle et al., Reference Kittle, Watson and Fernando2012). This study site included eight tea estates located immediately north of Peak Wilderness Sanctuary (Fig. 1), the region's largest protected area. Most cattle owners are workers on the tea estates and rear cattle for secondary income. Cattle in this area are of a more productive breed and are not grazed in wildlife areas, but kept in enclosures. The Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust has worked in the landscape for > 4 years and confirmed that at the time of the study, no depredation incidents had been reported in Maskeliya.

Methods

Data collection

During May–August 2018, we (AU and research assistants) conducted 113 surveys (61 in Palatupana and 52 in Maskeliya; Supplementary Material 1) that included closed-ended, including Likert scale type (Likert, Reference Laurance, Carolina Useche, Rendeiro, Kalka, Bradshaw and Sloan1932), and open-ended questions. We endeavoured to survey at least 50 cattle owners at each site. The survey covered themes related to human–leopard interactions, including socio-demographic parameters, cattle demographics, husbandry and mitigation techniques, livestock depredation, importance of conservation, awareness of leopard ecology and economic benefits, and attitudes towards leopards. Surveys were conducted without leading or directional questions about conflicts involving leopards, to avoid bias (Treves et al., Reference Thorn, Green, Marnewick and Scott2006). We define an attitude as a tendency to respond more or less favourably to a psychological object that represents an aspect of an individual's world (e.g. an issue, behaviour or action; Fishbein & Ajzen, Reference Fernando2010). We characterized attitudes towards leopards using a composite score based on eight attitude statements. Statements were ranked on a 5-point Likert scale, with a balanced number of positive and negative statements (Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig and Jones2000).

Our target population for the surveys were cattle owners who penned and/or grazed their cattle in areas where leopards were present. In Palatupana, we conducted purposeful sampling (Cresswell & Plano Clark, Reference Cresswell and Plano Clark2011) to ensure we captured a broad range of husbandry practices and cattle rearing experiences. Some respondents had participated in a corporate social responsibility programme operated by a nearby hotel, which provided steel enclosures to protect cattle. In Maskeliya, we contacted eight tea estates located near Peak Wilderness Sanctuary that were part of a more extensive study conducted by the Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust, and gained permission from each estate superintendent to survey cattle owners. We obtained informed consent orally from all respondents before conducting surveys and interviews.

We pre-tested 8–10 surveys at each study site to ensure respondents had a clear understanding of the questions, and modified questions as needed. Pre-test surveys were excluded from subsequent analysis. We administered surveys in Sinhala in Palatupana and Tamil in Maskeliya. During the survey, we used photographs of wildlife species to ensure they were not misidentified by respondents. We received assistance from community members familiar with the cattle-rearing community. In Palatupana, this was a safari guide who had lived and worked in the surveyed landscape for several decades and was knowledgeable about cattle rearing practices and the wider physical environment. In Maskeliya, each estate had a dedicated worker to assist us in recruiting respondents.

To provide additional context and nuance to the surveys, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a subset of 51 (32 in Palatupana and 19 in Maskeliya) of the initial 113 respondents, each lasting c. 15–20 minutes. Based on a literature review of human–wildlife conflict and communities, and existing knowledge of the region, we developed an interview protocol designed to explore themes of conflict mitigation, husbandry techniques, and barriers to cattle rearing in these landscapes. Following an iterative approach characteristic of qualitative analysis and inquiry (Cresswell & Plano Clark, Reference Cresswell and Plano Clark2011), we chose interview questions to help identify emergent themes relevant in this context (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008). Respondents were free to introduce additional topics they perceived as relevant. We did not ask questions regarding illegal activities such as killing of leopards, which could elicit distrust in respondents who may fear penalty; however, if they volunteered such information it was noted.

Interviews were transcribed and translated shortly after speaking with each respondent. We examined translated transcripts collaboratively with local field assistants shortly after each interview, to ensure subtext and nuances were captured accurately. We focused our analysis on husbandry techniques and barriers to cattle rearing faced by respondents, following an inductive approach (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006), to identify common themes across respondents.

Data analysis

We analysed all data using R 3.5.1 (R Core Team, Reference Packer, Loveridge, Canney, Caro, Garnett and Pfeifer2018). We characterized attitudes towards leopards from the survey results using χ² statistics and Fisher's exact tests. We used exploratory factor analysis to group survey item responses and attitude statement responses into a manageable number of variables, and to avoid over-parametrizing our models. Exploratory factor analysis identifies collinear variables and extracts factors by grouping strongly associated variables together (DiStefano et al., Reference DiStefano, Zhu and Mîndrila2009). For example, the variables ‘age’, ‘number of dependants’, and ‘length of time rearing cattle’ were grouped into a single factor, described as ‘socio-demographics’, which captures the relative influence of each comprising variable, for use in subsequent modelling.

We then created a weighted composite attitude score for each respondent by multiplying the responses to each attitude statement (Table 1) by the associated factor loading (Supplementary Material 2). This does not mask the individual effect of each question but weights each question separately. The resulting composite attitude score is continuous and on a relative scale, interpretable in comparison with other respondents within the sample. Cronbach's coefficient α was used to assess the reliability of this score, with standard requirements for internal consistency of α > 0.70 for non-clinical studies (Bland & Altman, Reference Bland and Altman1997). The resulting α value in Palatupana was 0.76 and in Maskeliya 0.65, with the latter value still being considered acceptable, particularly given the small sample size (van Griethuijsen et al., Reference Treves, Wallace, Naughton-Treves and Morales2015) and the Likert-type nature of the survey questions (Gadermann et al., Reference Fisher2012).

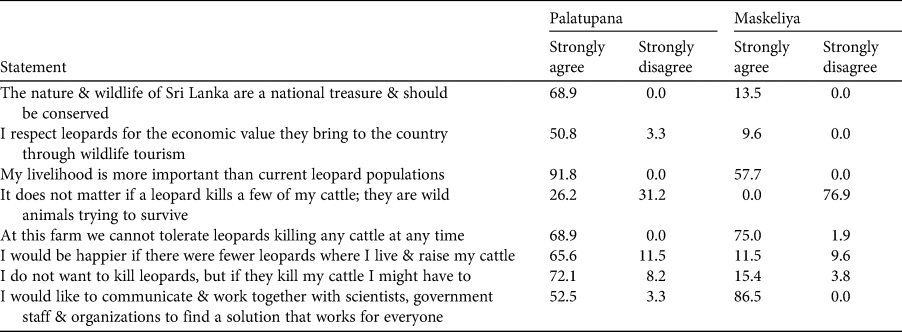

Table 1 Per cent of respondents who strongly agreed and strongly disagreed to eight statements relating to attitudes towards leopards in the Palatupana (n = 61) and Maskeliya (n = 52) regions, scored on a 5-point Likert scale. For complete results see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

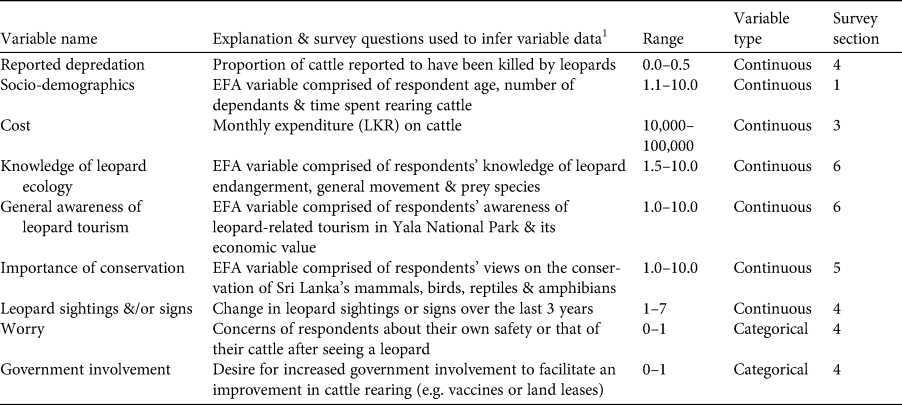

We used generalized linear models to examine the relationships between the composite attitude score (response variable) and determinants of attitudes (predictor variables; Table 2). Continuous variables were standardized to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one prior to regression modelling, to allow for direct comparison of effect sizes. We ran generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and log link because of the continuous response variable and right-skew of the data (Ng & Cribbie, Reference Naughton-Treves, Mena, Treves, Alvarez and Radeloff2017).

Table 2 Predictor variables included in regression models with their explanations and examples of survey questions used to infer variable data. The range of response values are given across both study sites. Survey section refers to the complete survey (Supplementary Material 1).

1 EFA, exploratory factor analysis.

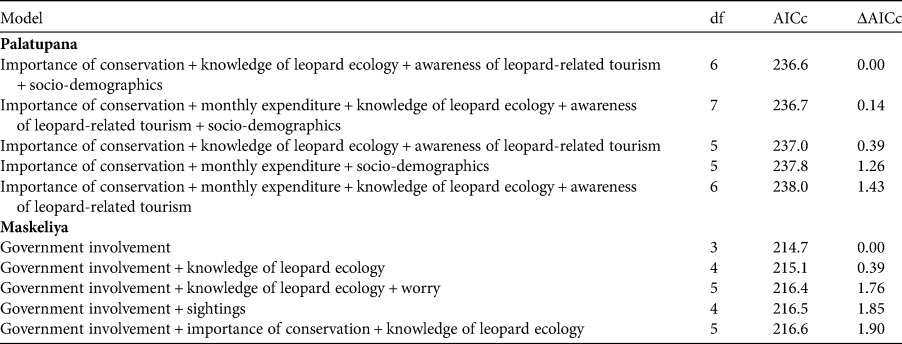

We ranked the performance of competing models that explained variation in attitudes towards leopards using the Akaike information criterion, corrected for small sample size (AICc; Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002). We assessed the appropriateness of the top-ranked models using residual diagnostics in the DHARMa package in R (Hartig, Reference Geffroy, Sadoul, Putman, Berger-Tal, Garamszegi, Møller and Blumstein2019) and used the adjusted proportion of deviance explained as a measure of model fit (Crawley, Reference Crawley2007). We ran separate global models for each study site, including first-order additive effects of the full set of predictor variables (Table 2). We compared these global models with a set of candidate models representing all possible first-order additive combinations of the variables. We ranked candidate models by their AICc score and considered all models with ΔAICc ≤ 2 compared to the top-ranked model (the one with the lowest AICc) as plausible (Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002).

Results

Attitudes towards leopards

Respondents in Palatupana had more negative attitudes towards leopards compared to those in Maskeliya (Table 1), most clearly evident by their level of agreement to attitude statements that pertained to cattle depredation and leopard populations. For example, 66% (40 of 61) of respondents in Palatupana indicated they would be happier if there were fewer leopards in the areas where they raised their cattle, compared to 12% (6 of 52) in Maskeliya (χ 2 = 13.95, P < 0.001). Similarly, 72% (44/61) of respondents in Palatupana strongly agreed they may have to kill leopards if these depredate their cattle, compared to 15% (8/52) in Maskeliya (χ 2 = 13.15, P < 0.001).

Respondents in Palatupana strongly agreed that the nature and wildlife of Sri Lanka are a national treasure and should be conserved (69%, 42 of 61), and that leopards should be respected for the economic value they bring to the country through wildlife tourism (51%, 31 of 61). This contrasted significantly with attitudes in Maskeliya (χ 2 = 33.05, P < 0.001 and χ 2 = 27.78, P < 0.001, respectively), where most respondents (c. 80%) gave neutral responses to these statements. The statement suggesting that respondents could tolerate the killing of a few of their cattle by leopards because the felids are wild animals trying to survive received a broad range of responses (indistinguishable from a uniform distribution across the five categories: χ 2 = 5.91, P = 0.206) from respondents in Palatupana, whereas the majority (77%, 40 of 52) of those in Maskeliya strongly disagreed. These differences in response distributions were highly significant (Fisher's exact test: P < 0.001). Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 provide full details of responses to attitude statements in both communities.

Determinants of attitudes towards leopards

We found that determinants of attitudes towards leopards differed between the two study sites. There was no reported livestock depredation in Maskeliya, whereas 93% of respondents in Palatupana reported depredation. Variables included in the top model for Palatupana included respondents’ knowledge of leopard ecology, awareness of leopard tourism, opinions on the importance of conservation, and socio-demographics (Table 3). Parameter estimates were similar across models close to the top model (ΔAICc ≤ 2). Respondents who thought that the presence of leopards in the buffer zones of protected areas would increase encounters between leopards and cattle had more negative attitudes (−3.41; 95% CI −5.77, −0.95; P = 0.008). Similarly, respondents who were more aware of leopard tourism had more negative attitudes (−0.38; 95% CI −0.65, −0.11; P = 0.009). Respondents who thought that wildlife conservation in general was important had more positive attitudes (0.15; 95% CI 0.10, 0.21; P < 0.001), as did those with high scores in the socio-demographics metric (0.04; 95% CI −0.01, 0.10; P = 0.09). The adjusted proportion of deviance accounted for by the top model was 46%. Models with ΔAICc ≤ 2 (compared to the top model) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Predictor variables included in generalized linear models to identify determinants of cattle owner attitudes (n = 61) towards leopards in Palatupana and Maskeliya, with associated degrees of freedom, Akaike information criterion corrected for small sample size (AICc), and difference in AICc from the best-performing model (ΔAICc). Models included are those with ΔAICc ≤ 2.

In Maskeliya, the top-ranked model (Table 3) suggested that a desire for increased government involvement in improving cattle rearing was associated with more positive attitudes towards leopards (0.31; 95% CI 0.16, 0.46; P < 0.001). The adjusted proportion of deviance accounted for by the top model was 21%.

Discussion

Determinants of attitudes towards leopards

Palatupana and Maskeliya differ in terms of histories, socio-demographics, depredation experienced, and cattle husbandry and characteristics. Concomitantly, our findings indicate that determinants of attitudes towards leopards also differed between the two communities. Attitudes towards leopards in Palatupana were more negative amongst respondents who thought that leopard presence in protected area buffer zones would increase encounters between leopards and cattle. Many respondents claimed that leopards prefer dairy calves over wild prey, stating that domesticated cattle do not react to leopards with the same anti-predator response that deer, boar and langurs exhibit (Geffroy et al., Reference Gebresenbet, Baraki, Tirga, Sillero-Zubiri and Bauer2020). This awareness of reduced anti-predator responses in cattle may have made those respondents feel more anxious about their calves and the security of their livelihoods, even with abundant wild prey in the area.

Similarly, cattle owners with greater awareness of the economic value of leopards held less favourable attitudes towards them. In Palatupana, leopard sightings within Yala National Park are a main tourist attraction, and those who are affected by negative interactions with leopards expressed frustration that they received no compensation and few benefits from the tourism industry. The income from tourism benefits primarily the local hotels and the government, and an increased awareness of these benefits combined with a lack of involvement in the tourism industry may cause resentment amongst cattle owners and lead to hostilities. Therefore, developing tourism programmes that include cattle owners (e.g. ecotourism, safari camps, hotels sourcing milk from local producers) could be an important step towards improving their attitudes towards leopards (Lindsey et al., Reference Likert2005; Hemson et al., Reference Hartig2009).

Respondents who supported wildlife conservation in general also had more favourable attitudes towards leopards. Similarly, as socio-demographic metrics increased (age, number of dependants and number of years spent rearing cattle), attitudes towards leopards were more favourable. Increased age, and thus a longer presence in the local landscape, may result in respondents being more tolerant of depredation incidents, a pattern that has been suggested previously (Mkonyi et al., Reference Mishra, Allen, Mccarthy, Madhusudan, Bayarjargal and Prins2017).

In contrast to the distrust felt towards the government in Palatupana, respondents in Maskeliya expressed greater hope that the government would lend assistance in resolving potential conflict concerning leopards. This difference is probably because Palatupana cattle owners have experienced poorer government relations over longer periods than those in Maskeliya, who are entirely dependent on tea plantation companies for their livelihoods. This dependence may be the reason for the cattle owners’ desire for greater assistance from the government. As cattle in Maskeliya are raised on lands owned by plantation companies, any government programme to assist cattle owners (e.g. by providing secure enclosures for cattle) would require permission from the respective plantation company before being implemented.

Barriers to cattle rearing

Our interviews highlighted differences in key constraints and issues faced by cattle owners in both study sites (Supplementary Table 3). The most frequently raised issue in Palatupana was the inability to lease or develop land for cattle husbandry, with 93% of cattle owners desiring some form of land or building rights for protective structures. All cattle owners agreed that the steel enclosures provided by the hotel's corporate social responsibility programme reduce depredation risk more effectively than the standard pens made from thorny bushes and barbed wire. However, local cattle owners cannot afford to purchase these pens, and those who did not receive one as a donation reported hardship.

The majority of respondents (72%) indicated that increased development has reduced available land, leading to overgrazing and reduced cattle productivity. Before the end of the civil war (1983–2009), there was less development and fewer vehicles, and cattle owners could camp by their cattle pens overnight for increased protection, which is now banned. The combined effects of not performing night-time patrols and the inability to erect semi-permanent structures were common themes of frustration.

Our interviews illuminated a common distrust of cattle owners in Palatupana towards the Sri Lankan government's Department of Wildlife Conservation, which has jurisdiction over the buffer zone adjacent to Yala National Park. Historical unrest and distrust continue to exist between these two groups, as cattle rearing in this landscape persists but its legality is not well defined. Our surveys revealed that only 9.84% of respondents reported incidents of livestock depredation to the Department for verification.

In contrast, in Maskeliya the most frequently raised issue was the need for improved infrastructure, indicated by 90% of cattle owners. Specifically, improvements were desired for cattle sheds and for the roads leading to the tea estates, which are unpaved and uneven. Poor roads restrict veterinary access, a serious issue for cattle owners, who reported a high rate of miscarriages, infections and hypothermia in their cattle. The poor condition of roads also hinders milk collection services, forcing many cattle owners to travel long distances on foot. The inability to own or lease land on the tea estates was another recurring issue in Maskeliya, where 84% of cattle owners expressed difficulty in acquiring the funds necessary (LKR 200,000–300,000; USD 1,100–1,650) to construct cattle sheds and were keen for a government-run loan programme to be initiated.

Potential strategies for human–leopard coexistence

Our findings from Palatupana indicate that being unable to own or develop land, along with lack of trust in the Department of Wildlife Conservation, were the main barriers to human–leopard coexistence. Improving communication between cattle owners and the Department, and developing a depredation reporting programme, could facilitate positive relationships. However, this is contingent on sufficient operational capacity of the Department, which may lack funding and staff. We recommend that prior to considering any land-use agreements, official buffer zone demarcations are first clarified and relevant jurisdictions of the Department of Wildlife Conservation and the Forest Department delineated.

Communal land ownership, whereby community members share the risk of livestock loss, may be an option to address constraints in land ownership. This approach has been shown to facilitate human–wildlife coexistence in Peru and central Kenya (Naughton-Treves et al., Reference Naidoo, Weaver, Diggle, Matongo, Stuart-Hill and Thouless2003; Romañach et al., Reference Ripple, Estes, Beschta, Wilmers, Ritchie and Hebblewhite2007). However, the potential impacts of granting restricted land ownership in ecologically sensitive regions (such as buffer zones of protected areas) need to be carefully considered. In Palatupana this could involve enforcing minimum distances away from the boundaries of Yala National Park, and limiting herd sizes to reduce grazing pressure and avoid overgrazing.

Cattle owners in Palatupana are affected by negative interactions with leopards but do not profit from leopard-related tourism, despite being aware of the regional economic benefits of this industry. A more equitable distribution of benefits is a fundamental goal of community-based natural resource management and integrated conservation and development projects, which have been successful in recovering wildlife populations and increasing community revenue and interest in conservation in Namibia and Nepal (Baral et al., Reference Baral, Stern and Heinen2007; Naidoo et al., Reference Mkonyi, Estes, Msuha, Lichtenfeld and Durant2016). However, using wildlife tourism to generate revenue for communities is a newer concept in South Asia, and any developments in this area need to consider local capacity (Sekhar, Reference Rostro-García, Tharchen, Abade, Astaras, Cushman and Macdonald2003).

Compensation schemes are another method used to alleviate loss of income caused by livestock depredation. In our study, 34% of respondents expressed an interest in receiving such compensation, and estimated a payment of c. LKR 100,000 (USD 550) per cattle lost to depredation to be adequate, based on the profit per litre of milk produced. However, compensation schemes may be prone to ‘problems of perverse incentives’ (Dickman et al., Reference Dickman, Macdonald and Macdonald2011, p. 13943), and a community-based livestock insurance programme (Mishra et al., Reference Madden2003) may be a more suitable alternative. Initially, these programmes require incentives, start-up funds and monitoring, providing an opportunity for future tourism sector corporate social responsibility programmes.

Depredation was not reported in Maskeliya, and attitudes towards leopards were related to a desire for increased government involvement, presenting an opportunity to proactively mitigate conflict. The government is promoting domestic dairy production, and efforts to alleviate some key challenges may help maintain positive attitudes towards wildlife conservation. Improving estate infrastructure and milk collection services, subsidizing prices for nutritional cattle feed and offering improved loans to help fortify cattle sheds are locally supported options.

For cattle-rearing communities and leopards to coexist and thrive in these landscapes, new strategies must consider the local context and attitudes. Further research should also consider factors not included in this study, such as personal and social motivations, behaviours and actions towards leopards, and whether or not a culture of tolerance exists (Gebresenbet et al., Reference Gadermann, Guhn and Zumbo2018). Given that Palatupana and Maskeliya are both landscapes where it is essential to work with local partners, we acknowledge the potential bias that may arise with this presence and encourage future research to similarly recognize this limitation. Ultimately, there is also a need to move beyond snapshots of current attitudes, towards longer-term studies that evaluate how attitudes change with changing social and environmental factors.

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork was supported by The Rufford Foundation, National Geographic Society and the City of Greenville Zoo; AU and ACB received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada, Canada Research Chairs Program, and the University of British Columbia Faculty of Forestry; AK and AW were supported by Cerza Conservation. We thank Al-fayed Mohammed, Parami Pieris and the Maskeliya estate superintendents and staff for help delivering and translating surveys; Cinnamon Wild Sri Lanka for providing accommodation and field assistance; all survey and interview respondents for their participation; and the University of British Columbia Wildlife Coexistence Lab for feedback.

Author contributions

Study design: AU, SH, AK, AW, ACB; data collection AU; data analysis: AU, with guidance from ACB, AK, EK; writing: AU; revision: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. Approval (H18-01121) from the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board was obtained prior to the surveys being conducted.