Scholars and policymakers debate how good diversity in the news media environment is for democracy. On the one hand, political communications scholars note that commercialization and new technologies have fostered more varied news formats and outlets that compete for niche markets. These trends, they argue, create fragmentation or “public sphericules” with little overlap and encourage selective exposure to like-minded news, undermining political communication and debate (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Ferguson1998; Gitlin Reference Gitlin, Liebes, Curran and Katz1998; Iyengar and Hahn Reference Iyengar and Hahn2009; Stroud Reference Stroud2008). One analysis of South Korean politics similarly notes that divisions among mass media outlets—both in terms of ideology and type of media—reinforce political polarization (Lee Reference Lee2005, 118–121). More optimistic assessments emphasize that targeted news, such as the partisan content associated with press-party parallelism, mobilizes voters in democracies worldwide (Baek Reference Baek2009, 384; Hallin and Mancini Reference Hallin and Mancini2004, 158; Van Kempen Reference Van Kempen2007). And democratic theorists see media diversity as encouraging a “marketplace of ideas,” in which minority voices can participate and citizens are exposed to multiple points of view (McQuail Reference McQuail1992, 142; Mutz and Martin Reference Mutz and Martin2001). Likewise, while Japan's relatively concentrated mainstream media have been accused of “capturing, subverting, misleading, or alternatively ignoring the political periphery” (Freeman Reference Freeman, Schwartz and Pharr2003, 236), the proliferation of online news outlets in Korea in the new millennium fostered broader political participation (Kwak Reference Kwak2011, 94–95).

From the perspective of activists seeking attention for their cause, however, the very forces democratizing access to news coverage in East Asia and beyond are paradoxically reducing the persuasive potential of publicity. Although activists in the digital age can cultivate support directly through their websites or social media, most groups still depend on the mass media, which have greater credibility and reach, to persuade bystanders and decision-makers of the worthiness of their cause. Activists aim not just to have their issue mentioned in the news (access), but also to obtain coverage that accurately conveys their claims (messaging) to large audiences (reach). While some scholars recognize these dimensions of news coverage, few have disaggregated access from messaging and reach—especially not in a comparative context. And few have examined how news production, distribution, and consumption processes in a given country may be more conducive to one dimension than another. Yet the structures and norms of each country's media sector create differing barriers to entry and foster distinctive modes of communication that affect activists’ efforts to promote their causes. As many countries, including Korea and Japan, are grappling with commercial pressures, and fragmentation in their media systems, as well as the rise of online news, scholars should pay more attention to the tradeoffs between diverse, accessible news media and media environments that help outsider groups garner the publicity needed to influence policy outcomes.

This article uses comparative analysis to examine the paradox of access—how characteristics of a media environment that render the news media more open to diverse voices can also limit the impact of an activist group's efforts to gain news coverage, and vice versa. Countries’ media environments exhibit varying degrees of diversity, depending on prevailing journalistic norms, media market and ownership structures, news format and content, outlets’ partisanship, and citizens’ news consumption habits. I hypothesize that new activist groups seeking policy change may have an easier time getting into the news in more diverse and fragmented media environments, but a harder time projecting a coherent message that reaches many people. Journalists in diverse media environments may be more receptive toward new groups, especially those that fit their political inclinations or generate “scoops.” But each group must then compete with more voices, and audience fragmentation limits the number of people a group can reach. More homogeneous media environments create higher barriers to entry for new activist groups seeking publicity and are subject to stronger gatekeeping by news companies and/or the government, but they also tend to help those groups that manage to break into the news to reach wider audiences with a more coherent message. I illustrate these dynamics by comparing the movements of victims of hepatitis C-tainted blood products in Japan and Korea.

My comparative examination of the Janus-faced implications of media environment diversity for activists makes two contributions to studies of social movements, media systems, and the public sphere. First, understanding when and how the media report on a group elucidates social forces that organize voices in or out of politics in democracies worldwide. Page (Reference Page1996, 23), for one, called for more research on the effects of “how concentrated or dispersed persuasive power [is]” and how diverse political stances are across news outlets. Yet social movement researchers often take media operations and structures for granted. This is largely the case among studies of movements in Northeast Asia, even though Krauss (Reference Krauss and De Vos1984, 172) long ago bemoaned the lack of attention to activists’ “silent partner”—the media—among Japan scholars (but see Reich Reference Reich and De Vos1984). For instance, Samuels’ (Reference Samuels2010) astute analysis of how the Japanese families of people abducted by North Korea were better able to “capture” policymaking processes than their South Korean counterparts fails to consider how differences in these countries’ media environments facilitated the Japanese abductee movement (see further Arrington Reference Arrington2013). At the same time, comparative media systems research tends to overlook East Asia, focusing more on North America and Europe (for a foray outside the West but not to East Asia, see Hallin and Mancini Reference Hallin and Mancini2011). I aim to draw these literatures more into dialogue.

Second, whereas prior scholars often conflate the process of getting into the news with the process of spreading an issue framing to wide audiences, I use a paired comparison to systematically show that attributes of a country's news media can have contradictory implications for these distinct processes. Rather than trying to explain movement outcomes or policy change (for such an analysis in the hepatitis C cases, see Arrington Reference Arrington2016, chap. 4), I focus on the effects of media environment diversity on news coverage of hepatitis C-related activist groups.

The relatively similar sociopolitical and judicial contexts of Japan and Korea, the contemporaneity and supra-partisan nature of these countries’ hepatitis C (HCV) victims’ activism, and the movements’ analogous tactics and claims enable me to conduct a “paired comparison” that minimizes potential confounding factors and isolates the impact that each country's media environment had on the publicity these movements received (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2010). After situating my theory in the existing literature about movement–media interactions, this article compares the Japanese and Korean media environments. It employs paired qualitative case studies, discourse analysis of HCV coverage, and an original panel dataset on newspaper coverage of HCV and other marginalized issues in both countries to show how surprisingly beneficial the relative homogeneity of Japan's mainstream media can be for activist groups that manage to break into the news, as that country's HCV movement did.

HOW MEDIA ENVIRONMENT DIVERSITY AFFECTS COVERAGE OF ACTIVISM

The news media play a central role in the processes of political participation and advocacy because they serve as gatekeepers of the public sphere, and they filter and package public discourse about sociopolitical issues. Activists seek media coverage to raise public and political awareness of their cause and thereby increase their bargaining leverage over decision-makers (Burstein, Einwohner, and Hollander Reference Burstein, Einwohner, Hollander, Klandermans and Jenkins1995; Lipsky Reference Lipsky1968). Media coverage also helps groups coordinate with their members and discern the opinions of the state actors they target (Gamson Reference Gamson, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004, 243–244; Koopmans Reference Koopmans2004). Mere mention of a group's grievance or protest is insufficient, however. And media coverage can be detrimental, such as when news reports undermine a group's credibility, sow dissent within a movement, or constrain a group's tactical options (Groth Reference Groth, Pharr and Krauss1996). Activists, therefore, try to get quoted in the news to signal their “standing” as legitimate news sources (Ferree et al. Reference Ferree, Gamson, Gerhards and Rucht2002, 9–13). They also aim to retain a say over their cause's framing in order to sway the policy options that officials might consider. Particularly effective framing “redefine[s] as unjust and immoral what was previously seen as unfortunate but perhaps tolerable” (Snow and Benford Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992, 137). Thus, media coverage shapes not only a social movement's tactics, access to resources, credibility, and efficacy, but also the broader public discourse about an issue, political agendas, policy options, and policy outcomes (Andrews and Caren Reference Andrews and Caren2010, 842).

Social movement scholars increasingly acknowledge the mediating role of the mass media (e.g., Gamson Reference Gamson, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004; Koopmans Reference Koopmans2004; Rohlinger and Brown Reference Rohlinger and Brown2013), but their predictions are often still ambiguous. The inconclusive debates about the effects of movements’ level of organization or their tactics on media coverage are particularly relevant for the case studies below. On the one hand, Gamson and Wolfsfeld (Reference Gamson and Wolfsfeld1993, 121) contend in their seminal study, professional planning, organizations, and resources are associated with more prominent media standing and preferred framing. An analysis of American pro-choice activism similarly argues that movements with staff tend to obtain more coverage because the staff can produce media packets and cultivate relationships with journalists (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1988). Interactions with reporters over time matter, as Reich (Reference Reich and De Vos1984) showed in his study of how Japanese reporters’ routines shaped their interpretations and reporting of information received from various sources. Furthermore, articulating grievances through institutional channels, such as the courts or conventional lobbying, is associated with getting coverage because it puts challengers into contact with reporters whose “beats” regularly cover these institutions (Oliver and Myers Reference Oliver and Myers1999).

On the other hand, whether due to profit concerns or the desire to produce stories that appeal to audiences, journalists and editors are often attracted by the drama of more contentious tactics and by human interest rather than professionalism. Gitlin (Reference Gitlin1980, 146–147) argues that the media's interest in personalizing the news has existed since the dawn of the mass commercial press and only grew with technological advances that enabled the media to convey real people's voices and then photos. Indeed, one study of activism surrounding US presidential campaigns discovered that activists who demonstrated “authenticity” as citizens with grievances tended to receive more coverage than those who cultivated “legitimacy through professionalism” (Sobieraj Reference Sobieraj2010, 524). Mazur (Reference Mazur1998) likewise found that local organizations of residents actually affected by the Love Canal pollution in the United States received more media attention than did officials.

In part, these studies offer orthogonal predictions about coverage of social movements because they do not distinguish how the processes of news production, distribution, and consumption might facilitate one dimension of media coverage more than another. By disaggregating questions of getting the media to cover one's issue (access) from questions of the message and reach of that coverage, and by drawing on political communications studies, this section elaborates a theory of how pluralistic media environments are a mixed blessing for activists. As others have noted, news media function as more than just neutral referees or gatekeepers, and their practices and organizational structures have significant effects on how they select and frame topics and arbitrate among different voices (Ferree et al. Reference Ferree, Gamson, Gerhards and Rucht2002, 12). I draw particular attention to the ways in which the news media's growing diversity and fragmentation are undermining the potential of news coverage to help movements convince bystanders and decision-makers to support their cause.

The disagreements over the benefits of media diversity for democracy that were described in the introduction stem at least partly from differing definitions of diversity and a tendency to focus on only some media characteristics. As an antidote, Napoli (Reference Napoli1999) offers a multidimensional conceptualization of media diversity that facilitates comparisons in terms of source, content, and exposure diversity. Source diversity describes how news organizations vary in terms of ownership structures, market shares, editorial priorities, and workforce composition, as well as each country's balance between local and national outlets. Scholars have found, for example, that ownership concentration tends to reduce the number of perspectives in the news, encourage soft news, and make the media less likely to challenge the state (Bagdikian Reference Bagdikian1985; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2004). Meanwhile, reporting and editorial practices shape news content, which can be diverse in terms of format, issues covered, perspectives included, tone, and duration of coverage. Hallin and Mancini (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004, 29–30) describe content as varying within a news outlet (“internal pluralism”) or across news outlets (“external pluralism”). Finally, indicators of exposure diversity include data about media outlets’ audience shares, generational or ideological divides, and citizens’ news consumption patterns, though these are notoriously difficult to ascertain (see Prior Reference Prior2009). These dimensions of diversity are interrelated, sometimes in opposite directions (Baker Reference Baker2007, 14). Increased choice in news, for instance, is associated with audience fragmentation and a reduction in the range of different perspectives or content that an individual encounters (Webster and Phalen Reference Webster, Phalen, Ettema and Whitney1994, 35).

Implicit in Napoli's discussion of diversity is a recognition of how different media interrelate to constitute a distinctive media environment in each country. A more explicit framework for describing and comparing the models of journalism, media market dynamics, and media–politics relations that prevail in a particular country is Hallin and Mancini's influential “media systems approach.” Their work has received little attention from social movement scholars, however, and is rarely extended to East Asia. I hope to rectify this. Hallin and Mancini posit that media systems vary in terms of the structure of media markets, the degree and form of connectedness to the political arena (“political parallelism”), journalistic conventions, and the state's involvement in media operations (Hallin and Mancini Reference Hallin and Mancini2004, chap. 2). A similar earlier study included the degree of integration among media and political elites and the partisanship of news outlets (Blumler and Gurevitch Reference Blumler and Gurevitch1995, chap. 5). My analysis below considers these characteristics, as well as how citizens consume and engage with different media. I prefer the term “media environment,” because segments of the media operate according to different principles, which the term “system” masks (McQuail Reference McQuail1994, 133). My conceptualization of a media environment also draws on field studies, which follow Bourdieu in analyzing how differentiated spheres of activity in modern societies develop distinctive interorganizational structures and norms over time (for more, see Benson Reference Benson2006). As shown in the next section, social learning processes shape interactions within the journalistic field, reporters’ conceptions of their work, and citizens’ expectations of the news media.

Due to such processes, some countries’ news media develop greater diversity in terms of their content and political stances across outlets, which both reflect and reinforce media market structures and audience fragmentation. Such is the case in Korea, as detailed in the next section. Rohlinger and Brown (Reference Rohlinger and Brown2013, 45) conclude from their analysis of academic freedom movements in the United States that such pluralistic media fields are more accessible to activist groups because non-mainstream reporters are often less concerned about groups’ reputations. Other countries, like Japan, develop comparatively homogeneous media environments, characterized by more ownership concentration, a preference for balanced reporting over product differentiation, and relatively isomorphic news consumption patterns. Although Walgrave and Manssens (Reference Walgrave and Manssens2000, 236) do not disaggregate access from messaging and reach, they predict that consensus mobilization is easier in media environments that are depoliticized and relatively homogeneous. The Japanese case resonates with their findings. But it also adds a cautionary note that such felicitous effects are conditional on a group first breaking into the news, which is difficult in more concentrated media systems because they are subject to stronger gatekeeping.

To analyze these dynamics, the next section identifies the constellations of attributes of the media (as opposed to any single attribute) that determine a media environment's source diversity, content diversity, and exposure diversity and thus constrain the processes of gaining media coverage, crafting a clear message, and reaching wide audiences. I hypothesize that media environment diversity facilitates access to the news but frustrates activists’ efforts to reach wide audiences with a coherent message (for a similar argument in a different context, see Evangelista Reference Evangelista1999). More homogeneous media environments do the reverse.

THE KOREAN AND JAPANESE MEDIA ENVIRONMENTS

Japan and Korea are ideal candidates for a paired case study on the effects of media environment diversity on activism. Not only are they relatively similar sociopolitically and judicially, but the news media in both countries were also historically criticized for excluding marginal voices and abetting the conservative political establishment, especially during Korea's authoritarianism (1950s–1987) and Japan's single-party democracy (1955–1993). Today, both countries are multiparty democracies with competitive elections, and their news media have transformed, albeit in different ways. Several scholars have analyzed the Japanese media and Korean media separately (e.g., Pharr and Krauss Reference Pharr and Krauss1996; Freeman Reference Freeman2000; Kabashima and Broadbent Reference Kabashima and Broadbent1986; Krauss Reference Krauss2000; Kwak Reference Kwak2012; Youm Reference Youm1994). But features of a country's media environment that one might take for granted become apparent through comparative analysis. Focusing on newspapers, TV, and the internet, this section explicates the ways in which Korea's media environment has become more pluralistic than Japan's in terms of source, content, and exposure diversity. As I demonstrate below through a paired comparison of media coverage of HCV-related activism in both countries, these differences mean that the Japanese mainstream media may be less accessible to outsider groups than are Korea's news media but groups that manage to break into the mainstream news in Japan are more likely to get the kind of coverage that persuades many bystanders to care about their cause.

Japan is a “media-saturated democracy” but its media environment is characterized by ownership concentration and relatively little diversity among mainstream outlets (Krauss Reference Krauss2000, 266). Despite regulations prohibiting cross-media ownership, Japan's main national dailies—the Asahi, Mainichi, Nikkei, Yomiuri, and Sankei newspapers—are each part of large business groups that practice “competitive matching” and own commercial TV and radio stations, weekly magazines, publishing houses, sports teams, and other businesses (Westney Reference Westney, Pharr and Krauss1996, 69). From 2008 to 2012, the Asahi, Yomiuri, and Nikkei even ran a joint website (allatanys.jp) that displayed the three papers’ top stories side-by-side. Although the main papers, listed above from liberal to conservative, have distinct editorial stances on some issues, such as Japan's war guilt or constitutional revision, they differ less in ideology and the issues they cover than do Korea's national papers. They also boast some of the largest circulations in the world, although, unlike in Korea, the largest regional newspapers in Japan rival the Nikkei and Sankei’s national circulation figures. Until the 1990s, Japan's public broadcaster NHK, which is legally required to be impartial, dominated over the five commercial broadcasters affiliated with each of the national newspapers, and regulations basically prevented new entrants to the market (Krauss Reference Krauss2000, chap. 7). The deregulation of cable and satellite TV and the rise of “info-tainment” talk shows in the 1990s drew some viewers away from NHK's famously pro-establishment and non-analytical news broadcasts (Noble Reference Noble2000; Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2007). Yet these shows’ content and formats remain relatively congruent, and audience sizes for NHK news programs are still nearly double that of the next most watched TV news programs (Collet and Kato Reference Collet and Kato2014, 43).

Korea's mainstream news media are more diverse, and market competition is fiercer. The 11 national newspapers vastly outsell any regional papers, represent a range of ideological positions, and compete by covering different topics. Korea's three largest and most conservative dailies—the Chosun, JoongAng, and DongA newspapers (nicknamed Cho-Joong-Dong)—still control nearly 60 percent of the market, partly due to benefits accrued while adhering to the authoritarian government's line in the 1980s. But at the other end of the political spectrum are the now-mainstream national papers, Hankyoreh and Kyunghyang, which feed off and contribute to progressive Koreans’ distrust of Cho-Joong-Dong. Founded in 1988, Hankyoreh touts a more “democratic” ownership structure than Cho-Joong-Dong and prides itself on covering more marginal groups and issues in Korean society. Between these ideological poles are several general and business-focused national papers. Before the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–1998, chaebol (conglomerates) or families owned most newspapers, but financial challenges diversified ownership structures (Kwak Reference Kwak2012, 72). Whereas NHK dominates the TV market in Japan, Korea's public broadcasters (KBS and MBC) and a commercial broadcaster (SBS) compete with a growing array of channels since deregulation in 2002. The Cho-Joong-Dong and Maeil Kyeongjae newspapers also launched four new general programming cable channels to take advantage of controversial and politically motivated deregulation in 2011. Thus, source diversity is greater in Korea than in Japan.

News content is also less diverse in Japan than in Korea. Over the course of decades of press freedom, Japanese journalists cultivated a reputation for objective thoroughness. Observers, however, often criticized Japanese reporters for engaging in “pack journalism” that supplied similar and unanalyzed minutiae as news and privileged government sources over independent investigation (inter alia O. Feldman Reference Feldman2005, 18–20; Van Wolferen Reference Van Wolferen1989). The Japanese media's most notable institutions—the reporters’ (kisha) clubs—were intended to give mainstream reporters equal access to officially validated information, but also tended to homogenize news content (Farley Reference Farley, Pharr and Krauss1996, 135–138; Freeman Reference Freeman2000). The clubs excluded reporters from non-mainstream or foreign outlets, who sometimes uncovered important scoops but did not gain regular access to officials until the Democratic Party of Japan's governments of 2009–2012 began giving extra briefings to non-club reporters. In the late 1990s, some newspapers created positions for roving columnists (henshūiin) who reported different perspectives.Footnote 1 But less than 20 percent of Japanese citizens surveyed in 2009 thought the national media paid attention to “society's weak” (NSK 2009, 49). Breaking into the national news remains difficult for new activist groups, therefore, even though many citizens and netizens criticized the mainstream media for unquestioningly reporting the government's line after the March 2011 earthquake-tsunami-nuclear disaster (McNeill Reference McNeill and Kingston2014, 65). The UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression also recently voiced “serious concerns” about the Japanese media's ability to report issues that the government deems sensitive (Murai Reference Murai2016). At the same time, the content isomorphism and “narrow, biased saturation coverage,” which Lynn (Reference Lynn2006, 484) argues “herd[s] the public into a relatively constricted range of views” and limits policymakers’ options, can be a potent tool for those activists who manage to gain coverage, as he shows with the families of Japanese nationals abducted by North Korea.

There are several dimensions on which news content can be homogeneous, but the extent to which different newspapers cover the same topics at the same time offers one indicator of content isomorphism across outlets. In conjunction with the paired comparison of media coverage of hepatitis C-related activism discussed below, I created a panel dataset of Japanese and Korean newspaper coverage of HCV and three other issues that similarly concerned bodily harm and government negligence and were relatively non-partisan. The other issues related to asbestosis and the problem of abuse of disabled persons in both countries, as well as Korean workers who developed leukemia while working in Samsung's semi-conductor and display facilities and Japanese patients who suffered adverse side-effects from the lung cancer drug, Iressa. In all these cases, movements formed and the issues gained at least some public and political attention in the past decade.Footnote 2 Special legislation was also passed in all cases, except in the Japanese disabled abuse case. Each observation in the panel dataset represents the number of articles that mentioned Samsung and leukemia, Iressa, disabled and abuse, or asbestos in a given month in a given national newspaper. I then calculated pairwise correlation coefficients on the level of coverage across time in each pair of newspapers in each country. The average pairwise correlations for each issue, reported in Figure 1, offer us a proxy for the congruity of news content across outlets in each country.

Figure 1 Comparison of News Homogeneity across Main Newspapers, Average Correlation Coefficients by Issue

On average (and in three of the four issues examined here) Japanese newspapers covered a given issue significantly more congruously than Korean ones did. The asymmetry in HCV coverage among Korean newspapers is extreme. Yet across the four issues, Japanese newspapers’ average pairwise correlation coefficient is 0.77, while Korean newspapers’ average is 0.51. Newspapers offer only one measure of media coverage and Korean newspapers still exhibit some congruity, but these findings indicate demonstrably less content diversity across newspapers in Japan when compared to Korean newspapers.

In part, Korea's relatively greater content diversity is a reaction to the recent authoritarian past, as well as to commercial pressures amid declining ad revenues. Government interference in the media and overt censorship in the 1980s (Youm Reference Youm1994, 112–114) and many Korean journalists’ experiences as political dissidents engrained a “skepticism of the government line” that renders reporters (including at mainstream outlets) more “open to new voices” than their Japanese counterparts.Footnote 3 Additionally, reporters’ clubs (gijasil), which were established under Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945), have become a lesser part of journalists’ routines because they were tainted by their association with authoritarian controls over the media. Moreover, Korean reporters tend to provide more analysis than Japanese reporters. Financial challenges encouraged outlets to “compete by offering distinctive content, often along ideological lines.”Footnote 4 In a 2008 survey, two-thirds of Koreans agreed that newspapers and broadcasters supplied “politically partial” stories (Rhee Reference Rhee2010, 53). The political sphere encourages such ideological differentiation. Since the 1990s, Korean presidents (from both sides), political parties, and individual politicians have at times favored reporters and news outlets that match their political leanings, indicating greater political parallelism than in Japan (see Haggard and You Reference Haggard and You2015). As Haggard and You note, charges of violating the National Security Law and rising numbers of defamation suits signal continued efforts by political elites to constrain or sway the media. But the greater content diversity in the Korean media than in the Japanese media, especially in the internet age, stems from a combination of all these factors.

Finally, citizens’ news exposure and consumption habits appear more congruent and traditional in Japan than in Korea, where audiences are more fragmented. While just nine percent of Koreans reported reading a newspaper daily in 2013, for instance, the percentage in Japan only fell from 70 to 56 between 2001 and 2013 (Korea Press Foundation 2013; NSK 2013, 34–35). And, although viewership hours are high in both countries, Korean TV audiences are more evenly spread among the main broadcasters than is the case in Japan, where NHK still predominates. Relatively high levels of public trust in the media also reinforce Japanese journalists’ sense that their audiences “expect objective news,” whereas “differentiated and often politicized content is considered attractive to Korean audiences,” especially amid falling ad revenues.Footnote 5

In addition, internet-based news providers have had more success in Korea than in Japan. Korea's hundreds of online news outlets, many of which are run by professional journalists, combine traditional journalism (e.g., Pressian) with innovations such as citizen journalism (e.g., OhMyNews), blogging, readers’ comments, or podcasts like Naneun Ggomsu Da, and they are popular (Kern and Nam Reference Kern, Nam, Shin and Chang2011; Kwak Reference Kwak2011). For example, live streams of police violence during the 2008 beef protests in Seoul attracted millions of viewers to Korea's OhMyNews site (Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Reference Lee, Kim and Wainwright2010, 364). In contrast, the Japanese version of OhMyNews lasted only four years after its launch in 2004 due to a dearth of visitors. Koreans also spend 500 more minutes per month online than Japanese do (Winseck and Jin Reference Winseck and Jin2011, 40). And in 2011, only 34 percent of Japanese named the internet as an “essential source of information,” compared to 56 percent for newspapers and 50 percent for TV (Yomiuri Shimbun Reference Shimbun2011). Japanese social media like 2channel, Mixi, Niko-Niko Dōga, and Twitter are also only gradually becoming platforms that facilitate political commentary, though this transformation accelerated after the March 2011 triple disaster, especially on Twitter.Footnote 6 Hence, while Japanese consume more congruent news in more congruent ways, Korea's media environment—encompassing both online and more traditional news outlets—is characterized by greater source, content, and exposure diversity.

METHODOLOGY

To illustrate how such differences in the media environments interact with activist groups’ efforts to gain coverage, send a coherent message, and reach wide audiences, the rest of the article conducts a paired comparison of media coverage of activism related to hepatitis C in Japan and Korea. In 2002–2003 and 2004, respectively, Japanese and Korean people who claimed to have contracted hepatitis C (HCV) from tainted blood derivatives mobilized to collectively sue the producers and government regulators. HCV causes inflammation of the liver cells and can lead to liver failure and liver cancer, though symptoms vary and chronic infections often progress slowly. Treatment is expensive and difficult. The plaintiffs in both countries sought compensation and medical subsidies, but struggled to prove which blood products had caused their infections and when government and industry decision-makers had had enough information about HCV contamination that their inaction could be considered negligent. Ultimately, the five Japanese courts hearing the HCV suits handed down rulings in 2006 and 2007 finding the state and producers liable, albeit for different periods of time and different blood products. In Korea, liability and causation were also contested. In February 2013, the Seoul High Court recognized a link between domestically made clotting factor and some of the plaintiffs’ HCV infections, but rejected the others' claims because the statute of limitations had expired. Both sides appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court, where the case is currently pending.

In the face of similarly lengthy court battles and continued denials of liability from the state and the manufacturers, Japanese and Korean HCV plaintiffs sought publicity to supplement their legal battles and associated activism. Through it, they hoped to gain public and political support for their claims and eventually catalyze special legislation providing compensation to all HCV victims since rulings or settlements in collective lawsuits (shūdan soshō in Japanese/ jipdan sosong in Korean), which are these countries’ closest equivalent to US-style class action lawsuits, only cover individuals actually listed as plaintiffs. These movements looked quite similar, in part because the Korean one involved so little of the coalitional activism that is common in Korea. They also both eschewed association with political parties to emphasize the supra-partisan nature of their claims. Both movements courted publicity through press conferences, press releases, and direct appeals to individual reporters. These movements’ similarities enable me to use the method of paired comparison to limit potentially confounding factors, such as the nature of the issue, the movements’ tactics, or the structure of the legal system, and focus on how each country's media environment shaped coverage of the HCV issue.

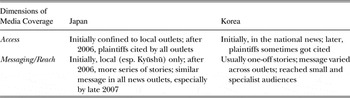

Disaggregating access from messaging and reach, I consider various qualitative and quantitative measures of the level, content, and impact of media coverage (summarized in Table 1). Discourse analysis of all articles about the HCV lawsuits in the main Japanese and Korean newspapers traces which actors were quoted when, the tone and language used, and issue framings or arguments included in coverage. I similarly analyzed the content of TV news stories (when available), online news articles, several special series in newspapers or on TV, and editorials about the lawsuits. I also interviewed two dozen Japanese and Korean journalists who had covered the movements and movement participants about media coverage.Footnote 7 The movements’ websites and newsletters provided further insights into their perceptions of the messaging and reach of news coverage.

Table 1 Summary of Indicators of Access, Messaging, and Reach

To supplement this qualitative analysis, I traced trends in coverage by collecting panel data on the number of articles that mentioned hepatitis C each month in each of the main Japanese and Korean newspapers’ national editions (morning editions in Japan). I used the KINDS database for Kyunghyang, Hankyoreh, and DongA and the JoongAng, Chosun, Asahi, Yomiuri, and Mainichi newspapers’ own digital archives. Not all articles necessarily focused on the movements, but this measure casts the widest net to discern the salience of hepatitis C as an issue. I also searched within these articles for references to the plaintiffs or to particular phrases that each movement adopted in its activism to analyze framing or messaging. In addition, I compared the aggregate monthly data on HCV coverage with the relevant “news hole,” which I calculated by tabulating how many articles each newspaper published per month on the Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare (MHLW) in Japan or the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) in Korea. Since Japanese newspapers on average run about two to three times as many articles per month on the MHLW than Korean newspapers do on the MOHW, it was important to analyze HCV coverage as a proportion of the news hole rather than in terms of absolute numbers of articles. I also calculated the correlation coefficients on each pair of newspapers’ coverage of HCV over time for a comparison of congruity across outlets in coverage of similar issues (see Figure 1 above). Combined, these qualitative and quantitative indicators reveal divergences in the overall level and the nature of media coverage of two analogous movements that I argue stem from characteristics of each country's media environment.

MEDIA COVERAGE OF HEPATITIS C-TAINTED BLOOD PRODUCTS IN JAPAN AND KOREA

Despite making similar claims and adopting similar tactics, the Japanese and Korean HCV movements received very different media coverage. The level of coverage related to HCV in each country’s main newspapers over time offers one indicator of this divergence. Figure 2 shows panel data on the average number of articles that mention hepatitis C per month in each country's main newspapers’ national editions as a proportion of the average number of articles related to the country's health ministry. Initially, hepatitis C received similar levels of media attention in Japan and Korea. As elaborated below, however, news reports in the early stages of litigation and activism included the perspectives of plaintiffs and their lawyers more often in Korea than in Japan, indicating greater media accessibility in Korea. But the Korean movement struggled to sustain media attention and reach large audiences with a coherent message. By contrast, members of the Japanese HCV movement didn't break into the national news for several years, but then received extensive and sustained coverage once they did. The main Japanese papers, for example, each devoted about 60 percent of their normal MHLW “news hole” to the HCV issue for several months in late 2007. The extent of this coverage relative to the news hole is especially surprising when one considers that the Japanese MHLW's jurisdiction is broader than the Korean MOHW's is. By late December, different types of media outlets in Japan were consistently reporting the movement's main demands, and Japan's five largest newspapers all ran editorials calling for compensation for HCV victims. The greater media attention to the HCV issue in Japan in 2007 exemplified what one Japan scholar called “saturation coverage” (Lynn 2006, 484).

Figure 2 Average Proportion of the Monthly “News Hole” Devoted to HCV in the Main Japanese and Korean Newspapers, 2002–2013

One could attribute such divergent media coverage to the small differences between these otherwise analogous movements. I do not deny that the two HCV movements had distinctive relationships to their countries’ lawsuits over HIV-tainted blood products, and that the movements differed somewhat in terms of the plaintiffs’ identities and the movements’ organizational structures and sizes. But, as I discuss next, these factors offer inconclusive predictions about media coverage. Consequently, I show below that a full understanding of the divergent media coverage requires examining the impact of differences in the Korean and Japanese media environments.

An Alternative Explanation: the HCV Lawsuits’ Relationship to HIV Litigation

Japanese and Korean victims of hepatitis C-tainted blood products followed thousands of victims of blood-borne HIV and HCV in the West by suing the manufacturers and state regulators and publicly blaming them for their infections (on HIV, see Feldman and Bayer Reference Feldman and Bayer1999). Across the developed world in the 1970s, patients with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders started receiving concentrated clotting factor. Although these new and more effective products were costly, they made treatment less inconvenient and time-intensive. Since producing factor concentrates involved pooling thousands of units of whole blood, however, one unit of virus-tainted blood could contaminate tens of thousands of doses. Epidemiological data led some US scientists to link rising rates of hepatitis among hemophiliacs in the 1970s to factor made from pooled blood, which was often purchased from high risk populations such as prisoners, drug addicts, and poor people (Allen Reference Allen1976). But factor concentrates’ effectiveness rendered hepatitis an “acceptable risk” for hemophiliacs (Institute of Medicine et al. Reference Leveton, Sox and Stoto1995, 8). And researchers did not identify HCV (previously called non-A non-B hepatitis) or develop a test for it until the late 1980s.

In fact, addressing hepatitis contamination in blood products did not become urgent until the early 1980s, when Western medical experts discovered a previously unknown disease, HIV/AIDS, in gay men and hemophilia patients. As in other developed countries, about half of Japan's hemophiliacs contracted HIV. Korea's hemophilia community avoided such an epidemic because few patients could afford the new concentrates. But the 25 Korean hemophiliacs who contracted HIV did so around 1990, years after the developed world had addressed viral contaminants in blood derivatives (Cho et al. Reference Cho, Foley, Sung, Kim and Kim2006). HIV victims in both countries sued for compensation. Japanese HIV-infected hemophiliacs’ lawsuits ended in 1996 in a highly publicized settlement (Feldman Reference Feldman2000). Korean hemophiliacs’ 2003 lawsuit over HIV-tainted blood products, by contrast, overlapped temporally with the HCV lawsuit and was quietly settled in late 2013.

Due to the similarities between HIV- and HCV-contamination, HIV litigation had implications for both countries’ HCV movements. But the effects on media coverage of the HCV movements were mixed. The Japanese HIV movement, for instance, bequeathed to that country's HCV movement the highly familiar yakugai (drug-related damages) issue framing (Cullinane Reference Cullinane2005), experienced lawyers and, perhaps most importantly, journalists who understood the technical details of tainted blood products. Despite such “priming” effects, the Japanese HCV movement struggled initially to assert their voice in the national media, as detailed below. The Korean HCV movement, meanwhile, had to compete with the contemporaneous HIV movement for attention, but it also used journalists’ interest in HIV as an entrée for discussing HCV. The two HCV movements’ relationships to their countries’ HIV movements differed, therefore, in ways that cannot fully explain divergences in media coverage of the HCV issue.

Moreover, on the basis of coverage of HIV and the safety of the blood supply, both countries’ media were similarly receptive to discussions about public health concerns, which might have competed with or facilitated coverage of the HCV movements. Media in both countries avidly reported examples of lax regulation by the MHLW/MOHW or other gaffes, such as 50 million misplaced pension records in Japan, even while reporting about the HCV issue. Thus, the larger constellation of related issues also fails to account for the divergent coverage of HCV.

Another Alternative Explanation: Plaintiffs’ Identities and the Movements’ Organization

Differences in the Japanese and Korean HCV plaintiffs’ identities and the movements’ organization and size offer another potential explanation for the divergent media attention they received. Yet these explanations are also unsatisfactory. Like HIV, HCV spread to several different populations via blood derivatives in the 1980s as decision-makers worldwide debated countermeasures to HIV amid changing scientific knowledge. Today, about 60 percent of Korean and Japanese hemophiliacs who received factor before 1992 are infected with HCV. In addition, about 10,000 non-hemophilic Japanese contracted HCV from blood products (fibrinogen and Factor IX) that were prescribed unusually often in Japan in the 1970s and 1980s during labor or surgery. For strategic reasons, the Japanese lawyers who launched that country's HCV lawsuits accepted only the latter non-hemophilic HCV victims as plaintiffs. In Korea, all plaintiffs were HCV-infected hemophilia patients. Japanese HCV-related litigation began in 2002 with 16 plaintiffs filing two suits in Tokyo and Osaka. Additional lawsuits were filed in Fukuoka, Nagoya, and Sendai the following year and included about 250 plaintiffs by February 2008, when the first court-mediated settlement talks began. The single lawsuit filed in Seoul included 102 plaintiffs by December 2004. Only 77 of them appealed a district court's unfavorable ruling in 2007, and 44 appealed the high court's partially favorable ruling in early 2013. Despite such attrition, a greater proportion of HCV victims in Korea joined the lawsuit than did in Japan.

Yet existing scholarship, as discussed above, offers ambiguous predictions about what such differences in plaintiffs’ identities or their organizational resources should mean for media coverage. Arguably, journalists may have been more sympathetic toward the Japanese plaintiffs, who were mostly women and had contracted HCV from one-off exposure to factor concentrates. The Korean plaintiffs, by contrast, were all male and depended on weekly infusions of factor to treat their congenital bleeding disorders.

At the same time, the Japanese plaintiffs relied more on their lawyers and had to establish their organizational legitimacy from scratch because they had no pre-existing group with staff, such as the Korean plaintiffs had through the Korea Hemophilia Association (KOHEM). KOHEM, which had represented the interests of all 2,000 Koreans with bleeding disorders since the 1980s, not only facilitated plaintiffs’ initial mobilization but also subsidized the lawsuit, gathered medical records for the lawsuit, and coordinated publicity and lobbying efforts. KOHEM and its press releases gave journalists a credentialed source of information about tainted blood, the HCV lawsuit, and hemophilia.Footnote 8 The fact that strategic choice and a lack of interest on the part of potential partner organizations led KOHEM to engage in little of the coalitional activism that is so common in Korea may have reduced the number of civil society channels through which to spread awareness of its cause.Footnote 9 But it also helped KOHEM avoid some of the problems that often plague coalitional activism in Korea, such as an incoherent message or disputes over leadership and issue framing (e.g. Moon 2007).

The Japanese movement, meanwhile, was started by lawyers, who helped overcome the plaintiffs’ dearth of organizational resources and leveraged the plaintiffs’ authenticity as affected parties (tōjisha). About 150 Japanese lawyers, of whom two dozen were active, signed on to the plaintiffs’ legal teams (bengodan) at the five court sites.Footnote 10 Many had participated in the prior HIV lawsuits or other collective lawsuits and associated activism, and many willingly used contacts from prior activism to advance the HCV movement. By contrast, Korea's HCV plaintiffs started with four lawyers, of whom only one remained on the case for the entire decade. Moreover, while few Korean plaintiffs were available for media interviews, the Japanese plaintiffs and the supporter groups (shien dantai) that students and local citizens formed at each court site supplied journalists with authentic voices and personal stories with human interest appeal. In their identities and organizational resources, therefore, Japanese and Korean plaintiffs had different but both potentially potent means of appealing for media attention.

How the Media Environments Shaped Coverage of the HCV Movements

Hence, I argue that accounting for divergences in media coverage requires examining the effects of each country's media environment. From the start of litigation in 2002 until 2006, the Japanese movement received little helpful national coverage. Reflecting a global tendency that is particularly pronounced in the Japanese media, reporters privileged the government's position, which acknowledged the epidemic but not the government's liability for plaintiffs’ infections (MHLW 2002). When the Osaka and Tokyo lawsuits were filed in late 2002, for example, fewer than half of the articles related to HCV in the Mainichi newspaper even used the word “plaintiff.” Aside from similar and brief stories reporting the start of the five lawsuits in 2002 and 2003 or providing the plaintiffs’ lawyers’ contact information, Japanese news stories mentioning HCV focused more on the disease generally or medical treatments and health insurance coverage for it. National media also reported the government's decision in December 2004 to publish the names of clinics that had used unheated blood products that might have been contaminated in the 1980s, though few outlets noted that former patients would have to pay for HCV testing if they wished to do anything about this information. Only two of the Asahi newspaper's nine articles that month even mentioned the plaintiffs, who were the most visible victims of these contaminated products. The plaintiffs and their lawyers persevered, organizing press conferences and rallies on each court date, and reporters attended. But as one journalist recalled, “Only Fuji TV's late-night News Japan covered the hepatitis issue at the national level until 2006.”Footnote 11 That program's prolonged investigative series on hepatitis C was unparalleled but had a small audience.Footnote 12

Lacking national publicity, Japanese HCV plaintiffs focused on sustaining local support between court hearings, which occur once every few months in Japan (as in Korea). Japanese local news outlets’ independence and sizeable readerships facilitated this effort. Through press conferences, seminars at local universities, and flyers distributed in busy parts of town, the plaintiffs capitalized on their credibility as affected parties and the local media's interest in “personalizing the news” (Gitlin 1980, 146–147). Yamaguchi Michiko's decision in April 2003 to become the first plaintiff to use her real name (jitsumei genkoku) gave reporters in her region of Kyūshū a poignant story.Footnote 13 Yamaguchi and subsequent real-name plaintiffs spoke about their suffering and the meaning of the lawsuits on court dates, at rallies, and to local reporters, who were familiar with such tactics from the HIV and Hansen's disease (leprosy) movements of the 1990s and early 2000s. The plaintiffs, especially in Kyūshū, recall being recognized from local TV news in supermarkets, but the fact that a reporter in Tokyo mistook Yamaguchi for a lawyer in early 2006 indicated what Yamaguchi called “a distressing lack of national visibility.”Footnote 14

The Korean HCV movement gained national publicity with comparative ease. About a dozen reporters from national and online news outlets attended the press conference that the lawyers and KOHEM organized in Seoul announcing the lawsuit in July 2004 (Kim Reference Kim2004, 3). Unlike in Japan, all articles quoted the plaintiffs’ lawyers, indicating easier access. Yet the stories' content varied across outlets. The article in the progressive daily, Hankyoreh, was four times as long as the article in the conservative daily, Chosun (Kang Reference Kang2004). Hankyoreh also reported the plaintiffs’ emphasis on the abnormally high HCV infection rates among Korean hemophiliacs and quoted a MOHW official placing the burden of proof on KOHEM (Gil Reference Gil2004). The online newspaper, Pressian, ran a long and sympathetic piece that quoted the plaintiffs’ lawyers and explained the parallels with HCV epidemics in the West, for which victims had already received compensation (Kang Reference Kang2004). The broadcasters SBS and KBS, as well as Yonhap wire service, also ran stories on the new lawsuit.

While Japanese HCV plaintiffs had to earn legitimacy as news sources in reporters’ eyes, Korea's HCV plaintiffs began with credibility via KOHEM. But media interest was difficult to sustain. Several individual reporters, as opposed to news outlets, personally kept tabs on the movement. One KOHEM officer recalled early interest from a KBS reporter and an MBC reporter, whose son happened to have hemophilia.Footnote 15 Yet the low number of court dates presented little new news. Moreover, as one former KOHEM staffer explained, “it felt like the [blood product] manufacturer would arrange meetings with any reporter I contacted … And then call to apologize for not running a story.”Footnote 16 The defendants’ influence and the manufacturer's libel suit against a researcher allied with KOHEM in the HIV lawsuit may have deterred media coverage. If mainstream newspaper articles mentioned HCV, it was in the context of more majoritarian concerns about the safety of the blood supply or the high cost of hemophilia treatment (which was “not helpful for the movement”Footnote 17 ). Most of the coverage the movement received after 2004 was in online or niche medical news outlets. For instance, when the GNP lawmaker Ko Gyeong-hwa revealed during the 2005 legislative audit of the government that the Korean National Red Cross and the blood derivative manufacturer had concealed the distribution and use of tens of thousands of units of HCV-tainted blood the previous year, only the online newspaper Pressian and specialist outlets like Daily Pharm and Medicate News reported the story. Thus, the Korean media were accessible but media segmentation hampered the movement's efforts to spread a coherent narrative.

By contrast, while the homogeneity of Japan's national media initially posed high barriers to entry and constrained coverage to local outlets, it proved felicitous once the HCV movement broke into the national news. This occurred when a journalist from the Mainichi newspaper, who had known the plaintiffs’ lawyers since covering HIV in Kyūshū in the 1990s, “convinced” his editor to run “an unprecedented series of five articles on the HCV movement” in the paper's national edition in early 2006.Footnote 18 The Mainichi series gave visibility and legitimacy to plaintiffs’ newly formed national organization (genkokudan), which their lawyers thought might provide national reporters with a clear point of contact.Footnote 19 Indeed, reporters from all national outlets contacted the plaintiffs' organization when the Osaka court ruled in some plaintiffs’ favor in June 2006. The series’ author also arranged meetings for plaintiffs with key editors and journalists in the wake of that ruling and another partly favorable ruling in Fukuoka in August.Footnote 20 Rulings offered official validation to some plaintiffs’ claims, but they were also inconsistent and rapidly appealed. News stories continued to frame the HCV issue as a dispute over the state and manufacturers’ alleged misconduct.

Ultimately, though, the relatively low content and exposure diversity in Japan's media environment helped plaintiffs articulate and spread a story that incited public indignation against the government and the producers. The movement's decision to re-release the “418 List” in autumn 2007 highlights how this occurred. This list, originally sent to the MHLW by a manufacturer of blood derivatives in 2001, included the names and infusion dates of 418 HCV victims, proving that the company had known that its product had infected people and that the MHLW had failed to inform victims. MHLW officials had given the list to members of the ministry's reporters’ club in 2002, but it received little publicity because officials had not flagged it. The list's re-release by the movement in late 2007 was choreographed for impact. Lawyers alerted journalist friends, a DPJ politician referenced the list in the Diet, and plaintiffs on the list were available for media interviews (Iwasawa Reference Iwasawa2008, 239). Japan's reporters’ clubs gave the movement “clear targets” as they notified journalists about the list.Footnote 21 Competing for the same story, all news outlets covered the list.

Several indicators suggest that most Japanese citizens had been exposed to coverage of the HCV movement by late 2007, although assessing the reach of media coverage is difficult. For example, Japan's main newspapers each published scores of articles on HCV each month throughout fall 2007 (see Figure 2 above). This deluge of coverage was relatively sympathetic to the movement. By late 2007, more than two-thirds of Japanese newspaper articles on HCV mentioned plaintiffs and/or their lawyers. More importantly, the movement's key demand of ichiritsu kyūsai (uniform financial assistance [for all victims]) began appearing verbatim almost daily in December 2007 after never appearing previously. The level of media attention to the HCV issue also looked very similar across the main Japanese newspapers. According to pairwise correlation analysis of panel data of coverage in each paper from January 2002 to December 2010, the Yomiuri’s coverage was correlated at a level of 0.91 and 0.92, respectively, with the Mainichi and Asahi newspapers’ coverage. And coverage in the Asahi and Mainichi was correlated at the 0.95 level.Footnote 22 In addition, all five main newspapers—the Asahi, Mainichi, Yomiuri, Nikkei, and Sankei—ran editorials on the same two days in late December 2007 calling on the state to compensate victims. Similar levels of coverage and content across TV stations and online outlets helped the plaintiffs’ claims reach wide audiences. As indicators of the reach, a plaintiff collecting signatures of support in downtown Tokyo noted that “most passers-by recognized [her] from TV,”Footnote 23 and 87 percent of Japanese respondents in one poll thought that the prime minister should draft legislation to compensate all HCV victims.Footnote 24

In contrast, the average Korean citizen would have had difficulty piecing together a coherent picture of the plaintiffs’ claims about the government and producer's liability for their HCV infections, since Korean news outlets compete for market share by diversifying and targeting narrow sub-audiences. Even HCV victims’ main ally in the National Assembly recalled not knowing that they had filed a lawsuit when she promoted blood safety legislation in 2005.Footnote 25 And no outlets devoted sustained attention to the issue. The movement elicited one-off stories from the Kyunghyang, JoongAng, and Chosun newspapers in fall 2007, when the court handed down its first ruling (against the plaintiffs). But even when some plaintiffs won their appeal in February 2013, the same newspapers, KBS, and the wire service Yonhap ran just one story each. Only Yonhap even mentioned the 2011 landmark Supreme Court ruling in the closely related HIV lawsuit. Thus, although the issue made it into the mainstream media, no outlets—traditional or online—engaged in sustained or in-depth reporting.

The Korean media environment left KOHEM little choice but to seek publicity whenever possible. Initially, HCV victims decried their country's “authoritarian medical administration” and claimed to promote the rights of all who have suffered from a “medical world distorted by money” to tap into master frames related to Koreans’ battles against authoritarianism and chaebol dominance (KOHEM 2004). Although this effort found little resonance in the media, except in a program about the safety of the blood supply on KBS's Chujeok 60bun in 2004, it mirrored a common tendency observed among civil society groups in Korea to feel compelled to fit into existing political agendas (Kim Reference Kim2009; Moon Reference Moon2007). After also hiring a press agency in 2006 and 2010 to little avail, KOHEM collected donations from within the hemophilia community in 2011 to pay for an ad in the JoongAng newspaper publicizing the Supreme Court's ruling in the HIV case and raising awareness of tainted blood products.Footnote 26 Yet the Korean media environment's diversity and segmentation impeded the kind of sustained coverage and consistent messaging that the Japanese movement had achieved.

Table 2 recaps the differences in media coverage given to the Japanese and Korean HCV movements along the key dimensions of access and messaging/reach. Although each country's media environment was not the only factor affecting these parallel movements, it is a crucial and often overlooked factor that had significant implications for public and political perceptions of the movements. Korea's relatively more diverse media environment helped HCV victims gain national news coverage early on but undermined their attempts to spread a coherent message to wide audiences. By contrast, the Japanese mainstream media's homogeneity posed high barriers to entry for HCV victims but helped them capture considerable attention and support once they finally broke into the national news.

Table 2 Summary of the Case Studies

CONCLUSION

Few observers question the importance of media coverage for activists who seek public and political attention for their cause. Sympathetic media coverage enhances the impact of activism when it transmits and “dramatizes [grievances] in such a way that they are taken up and dealt with by parliamentary complexes” (Habermas Reference Habermas2006, 359). Some groups seem to elicit news coverage more easily than others. As others have shown, however, an issue or group's “newsworthiness” is socially constructed rather than inherent (Sobieraj Reference Sobieraj2011, 81–83). Reporters’ habits, editorial priorities, commercial pressures, and audience expectations also combine to shape how an issue is framed and thus its resonance. Yet, as Bennett and Entman (Reference Bennett, Entman, Bennett and Entman2001, 6) note, “how the political communication environment shapes both information availability and the ways people use it in thinking about politics” is often taken for granted, including in East Asia.

To understand the effects that a country's media environment has on activism, I argued that we must decompose the distinct dimensions of “media coverage” into: (1) access and (2) messaging and reach. Doing so indicates that the very forces that are opening up the news media to more voices are also reducing the persuasive potential of publicity for activist groups. Activist groups may struggle to gain initial coverage in more homogeneous media environments, but they are more likely to sustain a coherent message that reaches wider audiences if they manage to break into the mainstream national news. Although Hallin and Mancini's media systems approach illuminates the constellations of media attributes that social movement scholars should consider, it overlooks these paradoxical effects of media environment diversity and the ways in which citizens’ news consumption patterns interact with media systems. Future research should investigate further the extent to which my argument holds in other national contexts. The Japan-Korea comparison suggests that the implications of media commercialization will vary cross-nationally for reasons internal to each country's media field. Media environments may be relatively diverse or homogeneous in different ways or change over time, especially in the digital era. The news media also interact in distinctive ways with dominant patterns of activism, which tend to be more coalition-oriented in Korea and more issue-oriented in Japan (Lee and Arrington Reference Lee and Arrington2008). My analysis indicates that understanding how the media filter and convey political communication requires examining constellations of factors related to news production, distribution, and consumption through quantitative and qualitative data that capture such dynamic interactions.

More broadly, the parallel activism of Japanese and Korean victims of hepatitis C-tainted blood products draws attention to the contradictory implications that pluralism in a country's news media has for democratic processes. Although Korea's vibrant media enable different voices and perspectives to flourish in the public sphere, they can also impede activists’ efforts to craft focused messages and retain social and political support. Coalitional activism is a similarly double-edged sword (e.g., Moon Reference Moon2007). Japan's comparatively homogeneous media may pose high barriers to entry for marginal voices, but they also offer those groups that do manage to break into the mainstream media potent tools for mobilizing the substantial support needed to compel concessions from the state. These attributes are arguably mutually reinforcing with Japan's issue-oriented and “victim-centered” model of activism (Avenell Reference Avenell2012). Neither situation is necessarily better for democracy, since victories for activists are not always victories for the rest of society. Grievance groups can also inhibit reasoned political debate and compromise. Moreover, they may render decision-making slower and more complicated, especially in the face of litigation. The Japanese HCV case, though, highlights the unanticipated upsides of a relatively homogeneous media environment, which many consider detrimental to democratic debate. More broadly, these cases indicate that answering questions about when and how citizens leverage democratic processes to make claims requires understanding how the media environment shapes political communication about sociopolitical issues, sometimes in unexpected ways.