Editorial

Fifteen years ago, the society that produces this journal was established to advance research on the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD). But, as we show here, extending our previous work,Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson 1 DOHaD research has been more concerned with exposures in the fetal period than in any other window of development. This interest manifests as an abundance of studies on the potential effects of the health and lifestyle of mothers around the time of pregnancy on the health of their children. We argue that this focus reflects deeply-held assumptions, among researchers, clinicians, policy makers, the media and the public, that maternal pregnancy exposures are the most important, causal determinants of offspring health.Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson 1 We call for the DOHaD research community to recognize and challenge these assumptions.

Evidence of an imbalance

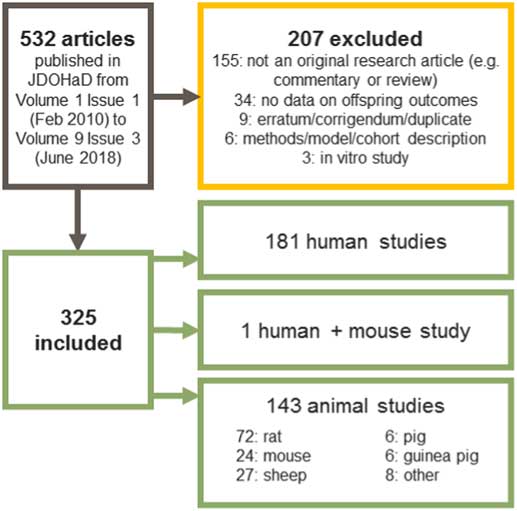

As shown in our previous article,Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson 1 nearly 20 times more papers have been published mentioning terms relating to DOHaD and ‘maternal’/‘mother’ compared to the same terms and ‘paternal’/‘father’. In an attempt to further quantify the scale of the DOHaD literature imbalance towards studies of maternal pregnancy exposures, we extracted information about each original research article published in the Journal of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease since it began almost a decade ago (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Summary of identification of articles for review. We extracted information on 325 articles published in journal of DOHaD from 2010 to 2018. Data extraction was performed independently by at least two authors, with any differences reconciled through discussion with a third.

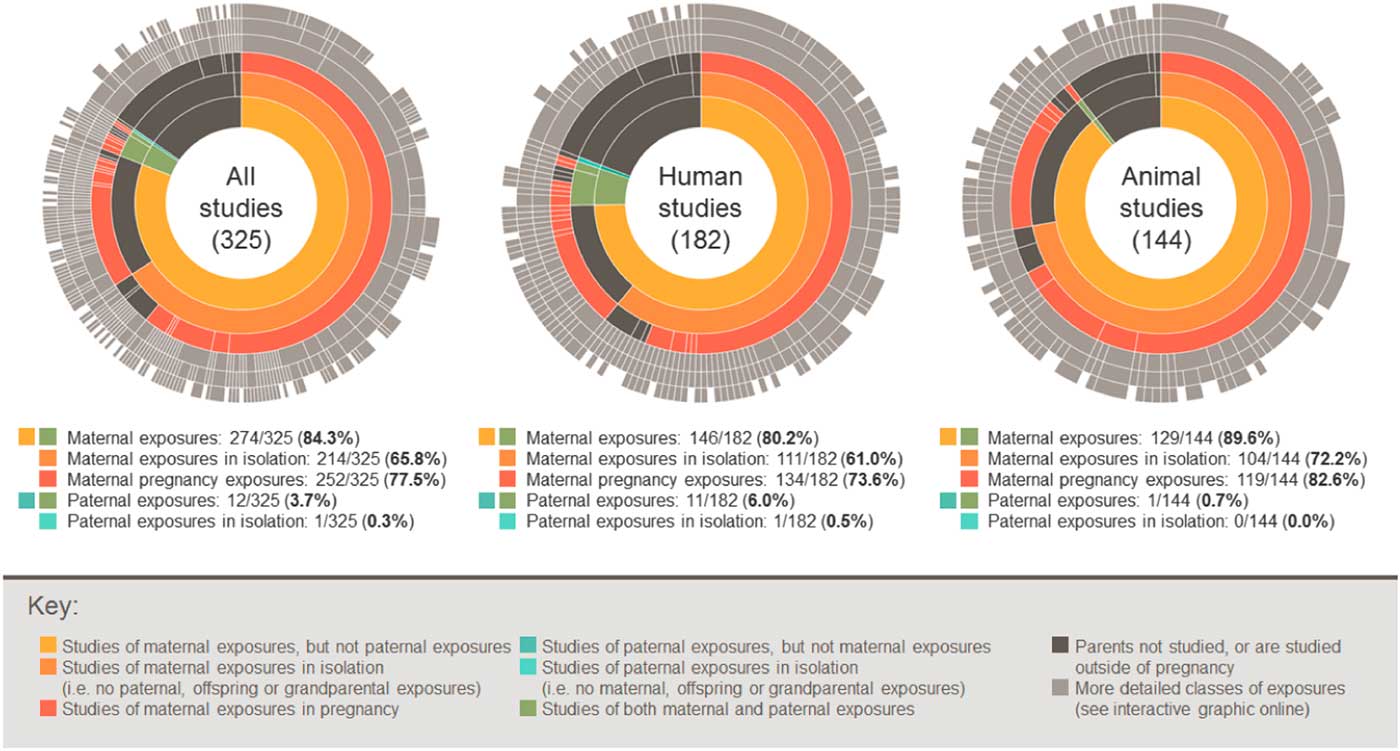

Of 325 eligible articles, 274 (84%) describe studies of maternal exposures, with 214 (66%) describing studies of maternal exposures in isolation (i.e. these studies did not consider paternal, offspring or grandparental exposures). Maternal exposures in pregnancy were studied in 252 articles (77%), with 167 articles (51%) reporting on maternal pregnancy exposures in isolation (Fig. 2). In stark contrast, only 12 articles (4%) described studies of paternal exposures (in any period) and only one study (0.3%) considered paternal exposures in isolation.

Fig. 2 Sunburst charts showing the proportion of studies considering different classes of exposures. An interactive version of this graphic is available at https://gs8094.shinyapps.io/sunburst/.

Where studied as exposures, we categorized fetal or birth characteristics (fetal growth and intrauterine growth restriction, birth size/weight, molecules in cord blood, gestational age at delivery and mode of delivery) as maternal pregnancy exposures, because these characteristics are often considered to be largely influenced by the intrauterine environment afforded by the mother during pregnancy. However, even if we reclassify these exposures as pertaining to offspring in all 52 relevant studies, there is still a striking imbalance towards studies of maternal pregnancy exposures (198 studies; 61%).

To allow readers to further explore all of the data that we extracted, we have produced an interactive version of the graphic presented in Fig. 2 (available at https://gs8094.shinyapps.io/sunburst/). Using this web app, readers can view more specific information about exposures, subdivide into animal and human studies and further explore the impact of classifying fetal/birth characteristics as pertaining to offspring or mothers during pregnancy. The web app also provides links to the data and code used in this analysis.

Why has DOHaD research traditionally focussed on maternal pregnancy exposures?

‘Mothers are easier to study’

Many human birth cohort studies take advantage of maternal health services to recruit mothers as the primary participant, often regarding them as the ‘gatekeeper’ to the recruitment of other family members.Reference Kiernan 2 Conversely, there is often less opportunity to recruit fathers directly and retain them throughout the study period. For example, researchers in the Born in Bradford study tried a number of strategies, including going to sports grounds, places of worship and working men’s clubs, but recruitment rates were still low compared to mothers.Reference Wright, Small and Raynor 3

Since these difficulties do not apply to animal studies, we might expect more animal studies of paternal exposures. However, we were surprised to find that our review of studies published in the journal of DOHaD suggests that this literature is similarly imbalanced: of 144 eligible animal studies, 129 (90%) considered maternal exposures, 119 (83%) in pregnancy and 76 (53%) in pregnancy in isolation (Fig. 2). This suggests that difficulties in studying fathers might make only a small contribution to DOHaD’s research focus on maternal exposures.

‘The scientific rationale for studying maternal pregnancy exposures is stronger’

The proximal and intimate relationship between a mother and offspring around pregnancy, and the potential for efficient health promotion during the antenatal period provides a strong rationale to study the influence of maternal pregnancy exposures on offspring health. However, with a few well-known exceptions (e.g. maternal smoking and birthweightReference Tyrrell, Huikari and Christie 4 ), the current evidence for a causal influence of most studied maternal pregnancy exposures on offspring outcomes is weak.Reference Mamluk, Edwards and Savović 5 – Reference Taylor, Carslake and Mola 8 Additionally, the relative contribution of maternal pregnancy exposures is difficult to ascertain because other exposures (including paternal exposures and postnatal offspring non-familial exposures) have not been studied with the same intensity. We would argue that with over two decades of correlative research on maternal pregnancy exposures with relatively little evidence of robust causal effects, there is currently no strong scientific rationale for continuing to focus research efforts on maternal pregnancy exposures so intensively.

‘It just makes more sense’

We argue that the main reason for the current imbalance in DOHaD research is that it reflects implicit, unquestioned and deeply-held starting assumptions that maternal pregnancy exposures are the most important, causal drivers of offspring health.Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson 1 This explains why, despite the lack of robust causal findings, DOHaD research on maternal pregnancy exposures is: (a) greater in intensity (and potentially quality), in both human and animal studies, than that on other exposures; (b) more likely to be published (publication bias is a factorReference Stern and Simes 9 ); and (c) more likely to be subsequently translated in the media, clinic and public health policy. In a looping effect,Reference Lombrozo 10 this wide public uptake of weak, but ‘common sense’ claims about maternal pregnancy effects reinforces assumptions about the causal primacy of maternal pregnancy exposures, which in turn further drives the over-focus of the DOHaD research agenda on the fetal developmental period.Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson 1

The potential negative impact of imbalanced DOHaD research

The potential impact of these assumptions, and the resultant imbalanced DOHaD research, is far from benign. It increases the risk of missing more appropriate, more easily modifiable targets for intervention. Paternal or postnatal factors might mitigate or amplify the effect of any maternal or pregnancy exposure and could yield more effective and less expensive intervention targets than maternal pregnancy exposures. For example, higher rates of smoking cessation in pregnant women are consistently associated with their partners’ cessation.Reference McBride, Baucom and Peterson 11 Additionally, pregnancy interventions designed to maximize offspring health can have adverse effects. For example, it is current practice to weigh women throughout pregnancy in an attempt to limit maternal weight gain to prevent offspring obesity. However, there is limited evidence that gestational weight gain has a causal effect on offspring adiposity and associated adverse cardio-metabolic health, or that it can be modified safely in pregnancy.Reference Lawlor 6 , Reference Lawlor, Relton, Sattar and Nelson 7 Conversely, the practice of continual monitoring of gestational weight gain and the pressure to conform to recommended levels that are not evidence-based may be associated with maternal anxiety.Reference Farrar and Duley 12

When DOHaD findings, despite a lack of causal evidence, are rushed into policy and clinical practice, concerns for the fetus are often placed above those of the mother. For example, the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPG) recently updated their recommendations for diagnosing gestational diabetes following DOHaD research highlighting the potential influence of gestational diabetes on the risk of greater offspring adiposity at birth and beyond.Reference Metzger and Gabbe 13 In a notable shift from previous decades, where the thresholds used to define gestational diabetes were directed towards reducing the future risk of maternal type 2 diabetes, the newly proposed IADPG thresholds are directed towards reducing birth size and future offspring overweight or obesity. The widespread use of these thresholds in clinical practice results in an increase in the number of women identified with gestational diabetes,Reference Farrar, Fairley and Santorelli 14 but any benefit for future offspring risk of obesity beyond birth is unknown.

In the media, DOHaD findings are often reported using alarmist, inflammatory language, with pregnant mothers presented as individually responsible for a host of specific harms to future generations, ignoring the societal systems that influence health behaviours. This public discourse can have coercive and autonomy-limiting effects for women, as we have previously described.Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson 1 , Reference Richardson, Daniels and Gillman 15 For example, a recent report by Amnesty International showed that fetal endangerment laws in the United States, designed to promote healthy pregnancies, discourage pregnant women who are dependent on drugs from seeking healthcare services for fear of criminal conviction. 16

Tackling the imbalance

The DOHaD field needs to remain critical of assumptions around the causal primacy of maternal pregnancy effects. To do this, we recommend:

1) collaborating with social scientists to consider the role of cognitive assumptions and the social and ethical implications of DOHaD research throughout the research cycle;Reference Müller, Hanson and Hanson 17

2) systematically reviewing and monitoring publication bias in the literature to further raise awareness of the current imbalance and help promote a cultural change;

3) collecting better quality data on other factors that influence offspring health, including social factors, postnatal life and partner/paternal factors (which should be straightforward in animal studies, and for human studies will involve working collectively nationally and internationally to promote the importance of exploring the effect of fathers on their child’s health and wellbeing);

4) improving and contextualizing the causal evidence base by scrutinizing the influence of these factors alongside potential maternal pregnancy effects using causal inference techniques;

5) accurately communicating DOHaD research in a way that does not sensationalize or overstate the findings, in both the academic literature and translations in the media, clinic and policy.

We are encouraged to see progress in these areas. For example, the recently launched WRISK project draws on women’s experiences to understand and improve the development and communication of risk messages in pregnancy.Reference Trickey 18 It is also encouraging to see the wider discussion of paternal exposures in the DOHaD literatureReference Soubry 19 , Reference Braun, Messerlian and Hauser 20 (although we are concerned that referring to the ‘Paternal Origins of Health and Disease’ or ‘POHaD’ continues the unhelpful reductionist attitudes that have contributed to the current focus on maternal pregnancy exposures and would suggest using a more systems-based approach).

We hope that strategies such as these will help ensure that DOHaD research supports effective policies and clinical practice to maximize the health of all family members.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

G.C.S., L.S. and D.A.L. work in a unit that receives funds from the University of Bristol and UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/5 and MC_UU_00011/6). D.A.L.’s contribution to this work is supported by grants from the US NIH (R01 DK1034) and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement (grant number 66945; DevelopObese). D.A.L. is a National Institute of Health Research Senior Investigator (NF-SI-0611-10196). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily any funders. The funders had no influence on the content of the paper.