In the aftermath of attacks on civilians in Western cities, psychiatrists, psychologists and criminal justice agencies have sought to understand the role of mental illness in terrorist offending. Reference Victoroff1–Reference Stevens3 An association has been reported between severe mental illness and terrorists who operate independently of others; 30–40% of these so-called ‘lone wolves’ appear to show signs of mental illness, isolation and marginalisation, which may make them suggestible and vulnerable to persuasion by terrorist ideology. Reference Corner and Gill4 Mental illnesses are 13 times more likely to occur in ‘lone wolves’ than in group-based terrorists, but mostly as a result of severe mental illnesses such as psychoses rather than depression. Reference Corner and Gill4,Reference Gill, Horgan and Deckert5 However, even lone wolves are not always isolated, suggesting there is no uniform profile. Reference Gill, Horgan and Deckert5 Compared with lone wolves, those who conduct school attacks and assassins are more likely to have signs of depression, despair and suicidal ideas, and a history of violence. Reference McCauley, Moskalenko and Van Son6

By contrast, terrorist plots and attacks in the UK, France, USA and Canada were, on the whole, organised by people without obvious symptoms of mental illnesses. 7 The perpetrators were born and educated in the countries that they attacked, and they seemed to be socially integrated. Without evidence of previous criminal activities or adverse life events, they fall into the category of offenders called ‘late starters’. 7 Links with organised terrorist groups are not easily identified, but communications through social media and websites, as well as exposure to extremist ideology, are often revealed during criminal investigations to have contributed to adopting extremist ideology. 7 Whether hidden or subthreshold mental illness plays a part in the recruitment of this group of ostensibly ordinary individuals is underresearched, but radicalisation is the process that is proposed by governments to explain this phenomenon.

The term radicalisation was first used following the Madrid 2004 and London 2005 bombings, Reference Christmann8 although its definition continues to evolve. The UK Prevent policy defined radicalisation as the process by which a person comes to support terrorism and forms of extremism leading to terrorism. We adopt a broader definition: a social and psychological process by which ordinary individuals come to sympathise with, and then make a commitment to, terrorist activities. Reference Horgan9,Reference Silber and Bhatt10 However, all definitions are explicit that radicalisation can exist without violence and extremist behaviour. Indeed, the 2011 revision of Prevent includes a broadening of what is considered radical, encompassing vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. 11 Despite the evolving shift in preventive frameworks and terminology, there is little empirical research into the process of radicalisation, and how this might differ in populations and specific groups, or about the role of psychological factors or common mental illnesses. The dominant explanation about radicalisation is that poverty, unemployment, discrimination, political isolation and cultural marginalisation lead to grievances, which in turn foster increased receptivity to political violence as a solution. 7 Adverse life events and poor civic engagement are associated with depression Reference Tennant12,Reference Viswanath, Randolph Steele and Finnegan13 and poor health Reference Gourion14,Reference Gluckman, Hanson and Beedle15 and are reported to engender extremism, 7,Reference Sousa16–Reference Ghosh18 suggesting some shared aetiologies for depression and extremism.

Sympathies for violent protest and terrorism (SVPT) are regarded as a ‘pre-radicalisation’ phase when individuals are vulnerable to recruitment to terrorist causes. We developed a measure of SVPT as a marker of susceptibility to engagement with extremist groups and actions. Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones19 We previously found an association between depressive symptoms and SVPT, Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones19 suggesting that these symptoms may drive cognitive biases leading to the adoption of extremist ideology and violence. Reference Victoroff1 The lack of hope and pessimism that characterise depression may increase the appeal of potent ideologies that promote agency and empowerment, and give purpose and meaning, even if related to criminal actions. Reference Victoroff1,Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones20 Further evidence in support of a potential role for depression comes from a recent meta-analysis that shows a three-fold increase in the risk of violence among those with depression. Reference Fazel, Wolf, Chang, Larsson, Goodwin and Lichtenstein21 Given the associations that exist between depression, social adversity Reference Brown22 and marginalisation, Reference Targosz, Bebbington, Lewis, Brugha, Jenkins and Farrell23,Reference Jobst, Sabass, Palagyi, Bauriedl-Schmidt, Mauer and Sarubin24 we hypothesised that depressive symptoms mediate relationships with SVPT.

Method

Participants

The study included 608 people of Pakistani and Bangladeshi family origin, aged between 18 and 45, of Muslim heritage and living in Bradford and East London. Bradford, an industrial town in northeast England, is home to a significant proportion of the Muslim population who live in isolated and traditional communities associated with deprivation. Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones19,Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones20 East London has a substantial and well-established Muslim population living in a region of greater religious and cultural diversity with wider opportunities for employment.

Participants were recruited by proportional quota sampling. This is a standard method that sets quotas for participants on a range of demographic factors and ensures that the sample interviewed is representative of the target population. Quota sampling offers an alternative to probability sampling and is often used in market research and national surveys as an efficient sampling strategy. Reference Rubin, Amlot, Page and Wessely25 Using UK Census 2001 data, quotas were set for each region to reflect the key demographic variables of those living there. Target quotas were set for age (18–30 years and 31–45 years) gender, work status (working full time, not working full time) and ethnicity (Pakistani and Bangladeshi). Data were collected from Pakistani and Bangladeshi men and women of Muslim heritage, given the concerns expressed in the media and in counter-terrorism responses focused on South Asians and people of Muslim heritage. In addition, these UK communities experience social adversity and marginalisation, and in our preliminary community discussions endorsed the need for more empirical research to inform preventive actions. Individuals living within a sampling unit were identified by door knocking and offered a computer-assisted interview if they gave informed consent. Flash cards were used to simplify the process of answering questions with choices.

Data collection was undertaken by Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute. All questions were refined following eight pilot interviews to check wording, sensitivity and questioning styles. Interviewers from Ipsos MORI were recruited from the local population, and had significant experience of research into sensitive topics including religion and terrorism. Questions were asked in a computer-assisted format with prompts and cues so that sensitive questions could be answered anonymously, out of sight of the interviewer. Piloting and the main study itself found that language or religious matching were not requested or necessary, although available. Informed consent was recorded by checking an appropriate box before proceeding with the survey. Ethical approval was received from Queen Mary University of London Research Ethics Committee.

Measuring SVPT

The 16-item measure designed to assess early signs of radicalisation asked about support for, or condemnation of, acts of protest characterised by differing levels of violence and extremist behaviour. Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones19 Sympathies are regarded as an early phase of vulnerability to radicalisation. Reference Silber and Bhatt10 The wording and items were developed through participatory discussions. Reference Ghosh18 We consulted Muslim and non-Muslim researchers and members of local community panels (consisting of local charities and mental health and educational organisations and religious institutions) about how to measure radicalisation. Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones19 The 16 core questions identified for inclusion had been proposed by and then reviewed by the community panel, and tested in pilot interviews. Reference Bhui, Warfa and Jones19 The questions were specifically aimed at being inclusive, rather than focusing on specific religious, cultural or ethnic groups as respondents. The responses were in the form of a seven-item Likert scale, ranging from −3 (completely condemn) to +3 (completely sympathise). For all but two items a higher score indicated greater support for violent protest and terrorism. These two items, which asked about sympathies for or condemnation of the UK government's decision to send British troops to Afghanistan and Iraq, were reverse-scored as condemnation might reflect a more radicalised perspective. The 16-item scale was found to be highly reliable, with a Cronbach's α = 0.81.

A cluster analysis of the 16-item measure of SVPT produced a three-group solution: a group that was least sympathetic (group 1, n = 93), a large intermediary group (group 2, n = 423) and a most sympathetic group (group 3, n = 92). The methods for generating clusters are already published; Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones20 a specific method of cluster analysis, a classification likelihood method, was applied to the 16 items. Reference Everitt, Landau, Leese and Stahl26,Reference Banfield and Raftery27 The Bayesian information criterion was used to determine the number of clusters. The clustering was carried out on the principal component scores from a principal components analysis of the original 16-item scores. The clustering was carried out using different numbers of principal component scores, and the most stable solution found was the one with the three groups.

Depressive symptoms were associated with membership of group 3 (which contains individuals who show most sympathy towards violent protest and terrorism) when compared with groups 1 and 2 combined, or group 2 alone. Depressive symptoms were not associated with membership of group 1 when compared with group 2, or with groups 2 and 3 combined. Therefore, we aggregated groups 1 and 2 to form a reference group to offer a comparison with group 3. Conceptually, this comparison is the most important in terms of understanding radicalisation.

Employment and education

Employment status was grouped into a three-level variable: employed (full time, part time or self-employed), unemployed, and an aggregated group who reported as retired, unwell or a housewife. Educational status included those having no qualifications v. any qualifications below degree level (GCSE/O-level/CSE, vocational qualifications such as NVQ1+2, A-level or equivalent such as NVQ3), and those having a degree (bachelor, master or doctorate).

Adverse life events

The measure of adverse life events included injury, bereavement, separations, loss of job, financial crisis, problems with the police or courts, theft and other major stressful events in the preceding 12 months. Reference Brugha, Bebbington, Tennant and Hurry28 For each adverse life event, a binary variable (yes/no) was derived.

Political engagement

The questions to assess political engagement were drawn from the UK Department of Communities and Local Government Citizenship Survey. 29 These questions addressed voting in local council elections, political discussions, signing a petition, donations to a charity or campaigning organisation, payment of membership fees to a charity or campaigning organisation, voluntary work, a boycott for political, ethical, environmental or religious reasons, political views expressed online, attendance at a political meeting, donations to or membership of a political party, and participation in a demonstration or march. 29 For each specific item of political engagement, a binary variable (yes/no) was derived.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a screening measure commonly used in primary care and specialist mental health services, with well-established validated thresholds for indicating risks of clinical depression. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams30 For the analysis, the total PHQ-9 score was classified into the following categories: PHQ score <5 and PHQ score ⩾5, where the latter indicates ‘probable clinical depression’.

Statistical analysis

A binary measure of sympathies for violent protest and terrorism was used in univariable and multivariable logistic regression models weighted for the sampling strategy and for non-response, thus yielding estimates attributable to the population from which the sample was drawn.

-

(a) All sociodemographic, life event and political engagement variables were assessed for associations with the binary outcome of SVPT and probable clinical depression. This information was used to undertake two further analyses.

-

(b) All variables significantly associated with the binary SVPT in the univariable analyses were included in the multivariable logistic regression models with one model for each life event and for each action of political engagement. These models were adjusted for age, gender, employment status, education level and depression.

-

(c) If specific life events and political engagement actions were significantly associated with both depressive symptoms and with SVPT, mediation models were employed to assess to what extent depressive symptoms explained the associations of life event and political engagement with SVPT. Reference MacKinnon, Fairchild and Fritz31 Where conditions of mediation analyses were met, we estimated what proportion of the direct relationship was explained by the indirect relationship through depressive symptoms.

The cluster analysis was implemented using the mclust package in R. All other analyses were performed in Stata 14. Statistical significance was considered at P<0.05.

Results

Demographic, health and social characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 show the distribution of demographic, social and health characteristics. The sample is primarily composed of 26 to 35-year olds, most of whom are employed and educated; 61% of this sample have a personal income between £5000 and £24 999. A total of 10% of the participants had experienced the death of a close friend or relative, and 10% had encountered a serious problem with a close friend, neighbour or relative; 62% of the sample voted in the last local council election, 41% donate money to charity and 19% undertake voluntary work. Only 1.4% reported a problem with the police or courts and 6% had been seeeking a job for one month or more in the preceding year. A fifth (22%) reported a PHQ-9 score indicating probable clinical depression.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics by sympathies for violent protest and terrorism (weighted)

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Groups 1 and 2 (n = 488) | Group 3 (n = 120) | All (n = 608) |

| Age groups, a years | |||

| 18–25 | 113 (23.68) | 42 (35.29) | 155 (25.98) |

| 26–35 | 249 (52.14) | 42 (35.82) | 291 (48.91) |

| 36–45 | 116 (24.18) | 24 (28.89) | 150 (25.11) |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 272 (55.79) | 59 (49.03) | 331 (54.44) |

| Women | 216 (44.21) | 61 (50.97) | 277 (45.56) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Pakistani | 223 (45.63) | 61 (50.78) | 284 (46.65) |

| Bangladeshi | 265 (54.37) | 59 (49.22) | 324 (53.35) |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 247 (50.45) | 59 (49.48) | 306 (50.26) |

| Unemployed | 97 (19.98) | 30 (24.94) | 127 (20.97) |

| Retired/ill/housewife | 144 (29.57) | 31 (25.57) | 175 (28.78) |

| Education | |||

| No qualifications | 93 (19.13) | 26 (21.63) | 119 (19.62) |

| <Bachelor degree | 239 (49.24) | 65 (55.31) | 304 (50.43) |

| Bachelor, Master, PhD | 153 (31.63) | 27 (23.06) | 180 (29.95) |

| Income b | |||

| <£5000 | 75 (23.12) | 9 (15.01) | 84 (21.86) |

| £5000–24 999 | 199 (60.96) | 34 (58.05) | 234 (60.51) |

| £25000–49 999 | 31 (9.45) | 12 (19.91) | 43 (11.07) |

| >£50 000 | 21 (6.48) | 4 (7.03) | 25 (6.56) |

a. n = 596.

b. n = 386.

Table 2 Social and health characteristics by sympathies for violent protest and terrorism (weighted)

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups 1 and 2 (n = 488) | Group 3, % (n = 120) | All, % (n = 608) | |

| Life events | |||

| Serious illness, injury or assault to a relative | 24 (4.89) | 1 (1.10) | 25 (4.14) |

| Death of a partner, spouse, parent or child | 16 (3.25) | 1 (0.42) | 17 (2.69) |

| Death of a close friend or relative | 57 (11.65) | 4 (3.64) | 61 (10.07) |

| Separation due to marital differences | 4 (0.86) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (0.69) |

| The end of a regular and steady relationship | 23 (4.69) | 3 (2.66) | 26 (4.29) |

| A serious problem with a close friend, neighbour or relative | 58 (11.81) | 6 (4.88) | 64(10.44) |

| Unemployment or seeking work unsuccessfully for 1 month or more | 28 (5.77) | 10 (8.51) | 38 (6.32) |

| Lost a job (fired, asked to leave) | 18 (3.68) | 1 (1.05) | 19 (3.16) |

| Major financial crisis | 24 (5.03) | 8 (6.38) | 32 (5.30) |

| Problem with the police or a court appearance | 4 (0.81) | 5 (3.81) | 9 (1.41) |

| Something valuable to you was lost or stolen | 23 (4.81) | 0 (0.02) | 23 (3.86) |

| Another major event that you found stressful not listed above | 35 (7.08) | 1 (0.88) | 36 (5.85) |

| Political engagement | |||

| Voted in the last local council election | 316 (64.92) | 60 (49.48) | 376 (61.86) |

| Discussed politics or political news with someone else | 122 (24.98) | 23 (19.34) | 145 (23.86) |

| Signed a petition | 125 (25.69) | 17 (13.79) | 142 (23.33) |

| Donated money to a charity or campaigning organisation | 222 (45.56) | 26 (21.97) | 248 (40.89) |

| Paid a membership fee to a charity or campaigning organisation | 30 (6.06) | 3 (2.73) | 33 (5.40) |

| Done voluntary work | 104 (21.30) | 10 (8.66) | 114 (18.80) |

| Boycotted certain products for political, ethical or environmental reasons | 24 (4.84) | 2 (2.07) | 26 (4.29) |

| Boycotted certain products for religious reasons | 43 (8.95) | 1 (0.40) | 44 (7.26) |

| Expressed my political opinions online | 16 (3.41) | 5 (3.98) | 21 (3.52) |

| Been to any political meeting | 10 (2.05) | 0 (0.13) | 10 (1.67) |

| Donated money or paid a membership fee to a political party | 17 (3.46) | 4 (3.12) | 21 (3.39) |

| Take part in a demonstration, picket or march | 19 (4.00) | 1 (0.71) | 20 (3.35) |

| Depression a | |||

| Patient Health Questionnaire score <5 | 339 (80.93) | 56 (62.09) | 395 (77.57) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire score ⩾5 | 80 (19.07) | 34 (37.91) | 114 (22.43) |

a. n = 509.

Univariable analyses

Table 3 shows that, contrary to expectation, those who had experienced the death of a close friend, a serious problem with a close friend, neighbour or relative, or another major event were less likely to have SVPT. People who had problems with the police or made a court appearance were more likely to report SVPT. As predicted, people who voted in the last election, signed a petition, donated money to charity, provided voluntary work or boycotted products for religious reasons were less likely to report SVPT. See online Table DS1 for odds ratios for demographic characteristics.

Table 3 Simple regression models: associations between sympathies for violent protest and terrorism and depression with social and health variables (weighted) a

| Sympathies for violent protest and terrorism |

Probable clinical depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (OR) (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Life events (no reference group) | ||||

| Serious illness, injury or assault to a relative | 0.22 (0.04–1.26) | 0.089 | 1.00 (0.38–2.64) | 0.999 |

| Death of a partner, spouse, parent or child | 0.12 (0.01–2.08) | 0.147 | 13.15 (3.83–45.17) | <0.001 |

| Death of a close friend or relative b | 0.29 (0.11–0.77) | 0.014 | 2.16 (1.18–3.94) | 0.012 |

| Separation due to marital differences | – | – | 0.39 (0.01–14.89) | 0.611 |

| The end of a regular and steady relationship | 0.56 (0.17–1.82) | 0.332 | 0.64 (0.16–2.58) | 0.532 |

| A serious problem with a close friend, neighbour or relative | 0.38 (0.16–0.92) | 0.031 | 1.39 (0.73–2.65) | 0.311 |

| Unemployment or seeking work unsuccessfully for 1 month or more | 1.52 (0.72–3.20) | 0.271 | 1.07 (0.45–2.54) | 0.876 |

| Lost a job (fired, asked to leave) | 0.28 (0.05–1.71) | 0.167 | 4.69 (1.70–12.95) | 0.003 |

| Major financial crisis | 1.29 (0.56–2.97) | 0.555 | 2.68 (1.12–6.44) | 0.027 |

| Problem with the police or a court appearance | 4.84 (1.24–18.86) | 0.023 | 5.15 (0.81–32.91) | 0.084 |

| Something valuable to you was lost or stolen | – | – | 1.79 (0.72–4.46) | 0.209 |

| Another major event that you found stressful not listed above b | 0.12 (0.02–0.81) | 0.030 | 4.72 (2.00–11.12) | <0.001 |

| Political engagement (no reference group) | ||||

| Voted in the last local council election | 0.53 (0.35–0.79) | 0.002 | 1.11 (0.72–1.72) | 0.625 |

| Discussed politics or political news with someone else | 0.72 (0.44–1.18) | 0.195 | 0.52 (0.31–0.89) | 0.016 |

| Signed a petition b | 0.46 (0.27–0.81) | 0.007 | 1.59 (1.00–2.52) | 0.048 |

| Donated money to a charity or campaigning organisation | 0.34 (0.21–0.54) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.44–1.04) | 0.076 |

| Paid a membership fee to a charity or campaigning organisation | 0.43 (0.14–1.38) | 0.158 | 0.86 (0.34–2.17) | 0.750 |

| Done voluntary work | 0.35 (0.18–0.69) | 0.002 | 1.46 (0.89–2.40) | 0.131 |

| Boycotted certain products for political, ethical or environmental reasons | 0.42 (0.11–1.56) | 0.193 | 2.17 (0.92–5.10) | 0.076 |

| Boycotted certain products for religious reasons | 0.04 (0.00–0.70) | 0.028 | 0.82 (0.37–1.83) | 0.621 |

| Expressed my political opinions online | 1.17 (0.42–3.31) | 0.761 | 3.40 (1.31–8.88) | 0.012 |

| Been to any political meeting | 0.06 (0.00–8.77) | 0.274 | 8.07 (2.07–31.42) | 0.003 |

| Donated money or paid a membership fee to a political party | 0.90 (0.29–2.80) | 0.852 | 1.85 (0.68–5.03) | 0.225 |

| Take part in a demonstration, picket or march | 0.17 (0.02–1.51) | 0.112 | 1.38 (0.50–3.85) | 0.537 |

| Depression (Patient Health Questionnaire score <5 as reference group) | ||||

| Patient Health Questionnaire score ⩾5 | 2.59 (1.59–4.23) | <0.001 | – | – |

a. See online Table DS1 for odds ratios for demographic characteristics.

b. Potential mediating effect of depression as associated with life events and political engagement and sympathies for violent protest and terrorism carried forward for mediation analyses, see Fig. 2.

Multivariable analyses

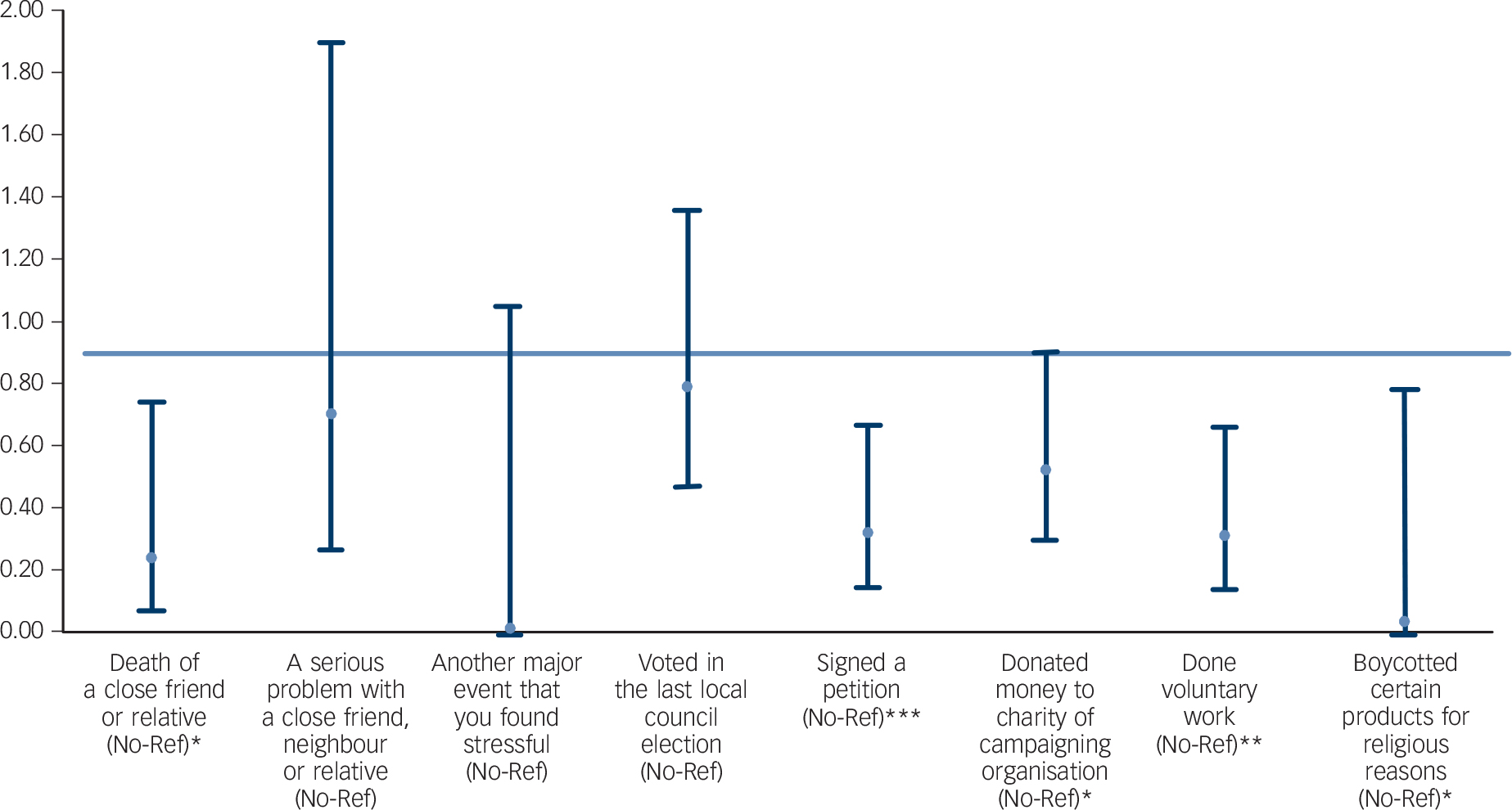

Figure 1 shows the relationship between SVPT, specific life events and acts of political engagement, with one model for each of the items. On the whole, the effects of life events and political engagement on SVPT were independent of probable clinical depression. Adjusted analyses (Fig. 1) suggest that death of a close friend (odds ratio (OR) = 0.24, 95% CI 0.07–0.74, P = 0.014), signing a petition (OR = 0.32, 95% CI 0.15–0.66, P = 0.002), donating money to a charity (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.3–0.9, P = 0.018), voluntary work (OR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.14–0.66, P = 0.003) and boycotting religious products (OR = 0.04, 95% CI 0–0.78, P = 0.033) are associated with a lower risk of SVPT. Another variable, major life events (not specifically defined by the questionnaire), falls just short of a significantly lower risk (OR = 0.01, 95% CI 0–1.05, P = 0.053), whereas contact with the police and courts falls just short of a significantly higher risk of SVPT (OR = 6.49, 95% CI 0.96–43.85, P = 0.055).

Fig. 1 Mulitvariable analyses: association between sympathies for violent protest and terrorism and demographic, social and health variables (odds ratios, weighted).

Logistic regression model for each life event or political engagement action in separate models (adjusted for age, gender, employment status, education level, depression; weighted). Most sympathetic group (n = 92) compared with least sympathetic and intermediary groups (n = 516). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. No-Ref: ‘no’ responses used as reference.

The aggregation of cluster groups in the analysis was driven by the association of a higher risk of depressive symptoms in group 3 compared with groups 1 and 2 combined. However, in order to aid interpretation of the findings, univariable analyses of life event and political engagement items by specific cluster groups were also undertaken. These compared group 1 (condemning) with group 2 (intermediate as reference) and group 3 (sympathetic). Boycotting religious products, signing a petition and voluntary work were associated with (lower risk) membership of group 3 compared with group 2 as the reference, but these items were also associated with a lower risk of membership of group 1 compared with group 2, suggesting that those who expressed most sympathies and most condemnation had lower levels of political engagement. In contrast, voting in the last council elections, donating money to a charity, and all the life event items were not associated with membership of group 1 compared with group 2, but showed an association (lower risk) with membership of group 3 compared with group 2.

Mediation analyses

Three items were potential mediators, showing significant associations with both probable clinical depression and SVPT (Table 3): death of a close friend or relative, another major life event, and signing a petition. Expressing a problem with the police or criminal justice agencies was strongly associated with SVPT, but less so with probable clinical depression. As a result, the effects were unlikely to be mediated by depression and this possible association was not considered further.

In the absence of depression, experiencing the death of a close friend or relative, another major life event, and having signed a petition are all associated with a lower direct risk of SVPT. Yet, when the three variables are accompanied by symptoms of depression, the risk of SVPT increases by a small amount. We found a lower overall risk of SVPT associated with political engagement and life events even in the presence of depressive symptoms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Mediation analyses for the role of depressive symptoms in explaining the relationship between life events, political engagement and sympathies for violent protest and terrorism: logistic regression showing direct and indirect pathways.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Pathways to SVPT

Specific life events are strongly associated with a lower risk of SVPT, whereas the effects are mostly independent of depression. Only contact with police or the courts carried a higher risk of SVPT, perhaps explained by past criminality or a heightened sense of injustice, leading to grievance and support for extremism. Yet, relatively few participants reported involvement with the police and courts and the variable was not strongly associated with probable clinical depression. Political engagement was also associated with a lower risk of SVPT, which is encouraging given the current UK emphasis on policies to promote political literacy and civic participation. These life events and acts of political engagement should not be used as markers of SVPT, as some types of political engagement (boycotting religious products, signing a petition and voluntary work) do not distinguish those at high and low risk of SVPT.

An association between adverse life events and depression is well established, invoking feelings of entrapment or humiliation, Reference Brown22,Reference Parker, Paterson and Hadzi-Pavlovic32,Reference Mumford, Nazir, Jilani and Baig33 underpinned by biological mechanisms of heightened amygdala activity and altered brain connectivity. Reference Anand, Li, Wang, Wu, Gao and Bukhari34,Reference Swartz, Williamson and Hariri35 We found depressive symptoms are associated with SVPT. However, the finding that life events appear to reduce the risk of SVPT is surprising, as adversity and inequality are often proposed to explain extreme beliefs and violent behaviour. 7 It is possible that losing a friend or relative might teach about the value of life and what it means to others to suffer a bereavement or loss, thereby deterring SVPT. Alternatively, adverse life events may cause people to draw on pre-existing social networks as a means of emotional support, creating opportunities to resolve disaffection and isolation. Yet, post hoc adjustments to the regression models for social support and the proportion of people from the same ethnic group made no difference to the estimates. This suggests that social support does not explain the effect, although there may be residual unmeasured or unknown influences.

Depression and violence

A recent systematic review suggested that depression predisposes participants to later offending. Reference Fazel, Wolf, Chang, Larsson, Goodwin and Lichtenstein21 Depression is also associated with impulsivity and suicidal behaviour, and these in turn are associated with risk of violence more generally. Reference Witt, Hawton and Fazel36,Reference Apter, Plutchik and van Praag37 In a previous paper, we found that the effect of depressive symptoms on SVPT is sustained when the analysis is re-run without the suicide item from the PHQ. Reference Bhui, Everitt and Jones20 This suggests that the association between SVPT and depressive symptoms is not because of suicidal thinking.

Alternatively, depressive symptoms may serve as a proxy for a number of other social concerns and psychiatric disorders. Reference Mumford, Nazir, Jilani and Baig33,Reference Bhui, Stansfeld, McKenzie, Karlsen, Nazroo and Weich38 Further research into these possibilities is needed. Preventing depressive responses to adverse life events and poor political engagement (or poor civic participation) may marginally reduce the risk of SVPT, but our findings suggest that promoting political engagement and social connectedness are more likely to have a larger impact.

Criminal justice system contact

The association between problems with the police or courts and SVPT suggests a subsample who have offended or come to the attention of law enforcement agencies. Violent offending linked with early exposure to adversity, such as material disadvantage and harsh or absent parenting in childhood, produces so-called ‘early starters’ who use substances, join gangs and offend. Reference Simpson, Grimbos, Chan and Penney39,Reference Ferguson, San Miguel and Hartley40 However, such influences have not been reported among the families of the recent perpetrators of terrorist attacks in the European Union and North America, where young men and women involved in terrorist actions appear to fall into the group called ‘late starters’; that is, they are relatively high functioning and offend after having encountered political ideologies or developed grievances or, less frequently, become violent because of developing mental illness.

Strengths and limitations

SVPT do not measure actual violence or terrorist offending, but their importance lies in the finding that such sympathies can create or accentuate vulnerability to persuasion and the adoption of the narratives of extremist groups. Reference Silber and Bhatt10 In recognition of the importance of cognitive rather than behavioural violence, Reference Horgan9 recent definitions of radicalisation include attitudes towards democracy, British values, and respect for the law and human dignity. Studies of terrorist offending and the emergence of extreme beliefs are important but ethically challenging, given the dilemma and risks of observing behaviour of increasing radicalisation. Furthermore, levels of support for terrorism fluctuate and are influenced by high-profile events and selection bias in sampling. For example, after the Charlie Hebdo attacks in France, 27% of a sample of British Muslims endorsed an item showing sympathy for the motives behind the attacks. Reference Hodges41

There are other reasons for trying to reduce SVPT. Sympathisers may serve as a pool for sustaining infectious ideas that, even if in the minority, polarise whole populations. Reference Deffuant, Amblard, Weisbuch and Faurs42,Reference Johnson, Madin, Sagarin and Taylor43 Radical ideas may be transformed into a practical threat if those who are sympathetic offer resources to terrorist groups. Reference Johnson, Madin, Sagarin and Taylor43 Reductions of the population prevalence of SVPT may be effected by encouraging political engagement and social inclusion in order to shift public opinion. Achieving this in young people and public institutions accords with the UK Terrorism Act of 2000, which mandates safeguarding duties for all citizens. Although this study suggests that depression may be a key pathway; more needs to be discovered about specific mechanisms of developing extremist ideas, preferably using longitudinal designs. Although cross-sectional data are not ideal for studying partial mediation, Reference Maxwell and Cole44 the bias serves to overestimate apparent effects. Our study found little support for mediation and, as longitudinal studies would reveal more conservative or no effect, these would be consistent with our findings.

Given the global importance of terrorism and the relative lack of research into the process of radicalisation, further studies are needed of other populations, and replication of the existing methods in different country contexts. Alternative sampling strategies, such as probability sampling, may be useful but would be expensive as large numbers of participants would be needed to complete the preliminary consent and screening procedure to assess their suitability for the study. For such a sensitive topic, this would raise ethical questions if the same research questions can be answered using quota samples. We did not assess personality disorders, which may be important correlates of offending behaviour, especially antisocial personality disorder. However, the notion of measuring personality across cultures is contested and diagnostic thresholds may differ across cultural groups. Reference McGilloway, Hall, Lee and Bhui45,Reference Ryder, Sunohara and Kirmayer46 Future research will need to grapple with these methodological dilemmas.

Funding

The study received no grant funding. The data collection was commissioned from Ipsos MORI. The statistical analyses were part funded by Careif, www.careif.org, an international mental health charity. Careif had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.