INTRODUCTION

With aging comes declines in cognitive ability (Raz et al., Reference Raz, Lindenberger, Rodrigue, Kennedy, Head, Williamson and Acker2005). Specifically, age-related decline in memory is the most pronounced. Age-related memory decline is known to result from exponential neuronal loss and impaired replacement of the lost cells (Kuhn, Dickinson-Anson, & Gage, Reference Kuhn, Dickinson-Anson and Gage1996; Morrison & Hof, Reference Morrison and Hof1997). Additionally, reduction in synaptic contacts plays a role in age-related memory loss (Detoledo-Morrell, Geinisman, & Morrell, Reference Detoledo-Morrell, Geinisman and Morrell1988; Foster, Reference Foster1999). Memory difficulties among older adults can dramatically debilitate their ability to perform daily living tasks, such as comprehending medication labels, using emergency telephone information, understanding transportation schedules, and driving (Leirer, Morrow, Pariante, & Sheikh, Reference Leirer, Morrow, Pariante and Sheikh1988; Vance, Wadley, Ball, Roenker, & Rizzo, Reference Vance, Wadley, Ball, Roenker and Rizzo2005).

Exercise is a viable intervention for maintaining quality of life in older adults (Rejeski & Mihalko, Reference Rejeski and Mihalko2001). Exercise has been shown to enhance brain health, improve cognitive function, and delay the onset of cognitive decline in elders (Cotman & Engesser-Cesar, Reference Cotman and Engesser-Cesar2002). However, less is known about the short-term effects of single sessions of exercise on indices of brain function during memory retrieval. These effects presumably accumulate over time to produce adaptations that benefit cognitive function. For example, in animal models exercise enhances neurogenesis, brain plasticity, and hippocampal-dependent learning and memory, suggesting it serves as a potential therapeutic tool for preserving and improving memory.

Indeed, converging lines of evidence in both rodents (Gómez-Pinilla, Ying, Roy, Molteni, & Edgerton, Reference Gómez-Pinilla, Ying, Roy, Molteni and Edgerton2002; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Huddleston, Brickman, Sosunov, Hen, McKhann and Small2007; Russo-Neustadt, Alejandre, Garcia, Ivy, & Chen, Reference Russo-Neustadt, Alejandre, Garcia, Ivy and Chen2004) and humans (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Voss, Prakash, Basak, Szabo, Chaddock and Kramer2011; Nouchi et al., Reference Nouchi, Taki, Takeuchi, Sekiguchi, Hashizume, Nozawa and Kawashima2014; Suwabe et al., Reference Suwabe, Byun, Hyodo, Reagh, Roberts, Matsushita and Suzuki2018; Vaynman & Gomez-Pinilla, Reference Vaynman and Gomez-Pinilla2006; Weinberg, Hasni, Shinohara, & Duarte, Reference Weinberg, Hasni, Shinohara and Duarte2014) have documented that increased leisure-time physical activity is associated with enhanced memory function. Among healthy younger adults, it is increasingly recognized that an acute bout of exercise can improve memory consolidation (Segal, Cotman, & Cahill, Reference Segal, Cotman and Cahill2012), short-term memory (Etnier et al., Reference Etnier, Wideman, Labban, Piepmeier, Pendleton, Dvorak and Becofsky2016), and long-term memory (Winter et al., Reference Winter, Breitenstein, Mooren, Voelker, Fobker, Lechtermann and Knecht2007). However, whether these effects occur in healthy older adults has not been clearly established.

Moreover, although the effects of acute exercise on memory have been examined extensively in younger adults, most studies of this nature have focused on perceptual or short-term memory paradigms and episodic memory (Nouchi et al., Reference Nouchi, Taki, Takeuchi, Sekiguchi, Hashizume, Nozawa and Kawashima2014; Ruscheweyh et al., Reference Ruscheweyh, Willemer, Krüger, Duning, Warnecke, Sommer and Flöel2011; Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Hasni, Shinohara and Duarte2014), while the association between exercise and semantic memory has received little attention. Given that the inability to remember familiar names is the most common memory complaint among older adults (Jonker, Geerlings, & Schmand, Reference Jonker, Geerlings and Schmand2000), investigating semantic memory may serve as a useful predictor of neurodegenerative disease. Furthermore, findings suggest that the semantic memory system is vulnerable to the earliest stages of cognitive decline (Henry, Crawford, & Phillips, Reference Henry, Crawford and Phillips2004; Lonie et al., Reference Lonie, Herrmann, Tierney, Donaghey, O’Carroll, Lee and Ebmeier2009). Therefore, research examining the impact of exercise on semantic memory is of great importance for understanding its therapeutic potential.

Beyond behavioral studies, recent advances in neuroimaging techniques, particularly fMRI, offer neurophysiological perspectives into the link between exercise and memory. Our research team has shown that two groups of older adults (cognitively intact and those with mild cognitive impairment) exhibit a significant reduction in semantic memory activation intensity after completing 12 weeks of moderate intensity treadmill walking relative to baseline. This study suggests that exercise may improve neural efficiency during semantic memory retrieval in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and cognitively intact older adults and may lead to improvements in cognitive function (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013).

Despite this evidence, our understanding remains limited regarding the effects of acute exercise on semantic memory activation in older adults. To our best knowledge, no study has observed semantic memory-related fMRI blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) activation immediately following a single bout of exercise in older adults. Considering that single bouts of exercise are the building blocks of chronic exercise (Basso & Suzuki, Reference Basso and Suzuki2017), understanding the changes induced by acute exercise may provide novel insight into the association between exercise and memory. Therefore, this study investigated the effect of acute exercise on BOLD semantic memory activation patterns using task-activated fMRI in 26 healthy older adults. Based on previous evidence (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013), it was hypothesized that acute exercise would reduce the magnitude and spatial extent of semantic memory-related functional activation compared to a rest condition.

METHODS

Participants

Thirty-two physically active, right-handed older adults (ages, 55–85 years) were recruited to participate in this study. Participants were pre-screened using a structured interview questionnaire, which included items specific to MRI safety (i.e., regarding the presence of metal implants, pacemakers, aneurysm clips, and other potential safety hazards) to ensure they could safely participate in the MRI scan. Participants were excluded if they reported a history of stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure, neurological disease, major psychiatric disturbance, substance abuse, or were taking psychoactive prescriptive medications. Before the first MRI scan, participants who were eligible attended the pre-screening session where they provided informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Maryland. They also completed the 7-day physical activity recall (Sallis et al., Reference Sallis, Haskell, Wood, Fortmann, Rogers, Blair and Paffenbarger1985) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975), a 30-point questionnaire used to screen for global cognitive impairment and dementia.

Participants were instructed to maintain normal eating habits and to refrain from eating for 4 hours, drinking alcohol for 12 hours, and from drinking caffeine for 4 hr before participation each day (Ferré & O’Brien, Reference Ferré and O’Brien2011). Participants who completed all experimental sessions were paid for their participation. This study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (World Medical Association, 2008). Demographic, physical, and cognitive data for all participants are provided in Table 1. Details of the recruitment process and inclusion in the final sample are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1 Demographic information, physical characteristics, and cognitive function of study participants

Note: SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; HR, heart rate; BPM, beats per minute; Age-predicted HRmax, Age-predicted maximal heart rate; HRresting, resting heart rate; 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Score, based on time spent in light, moderate, hard, and very hard activities during the seven days before enrollment in the study; kJ, kiloJoules; kg, kilograms.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of participant recruitment, eligibility screening, enrollment, withdrawals, and the final sample included in the fMRI analysis (n=26).

Exercise and Rest Conditions

Using a within-subject design, the order of the experimental conditions (exercise and rest) was counterbalanced across participants. During the exercise condition, participants completed 30 min of continuous cycling on a Monark cycle ergometer (Varberg, Sweden) located outside of the fMRI scanner. The rationale behind our choice of exercise intervention was based on a previous finding indicating that moderate exercise enhances cognition to a greater degree than light or high intensity exercise (Kamijo, Nishihira, Higashiura, & Kuroiwa, Reference Kamijo, Nishihira, Higashiura and Kuroiwa2007). Before each condition, participants were fitted with a heart rate (HR) monitor (Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland) and standardized instructions regarding the use of the Borg 6-20 Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale (Borg, Reference Borg1970) were provided before adjusting the seat height.

A 5-min warm-up session was then administered before the 20-min moderate-intensity exercise session. During the exercise session, participants were instructed to self-select their workload to meet an intensity corresponding to an RPE of 15 (associated with the verbal anchor “Hard”). Pedal cadence was maintained between 60 and 80 rpm while participants freely adjusted resistance. Immediately following moderate-intensity exercise, a 5-min cool-down was completed before participants were escorted to the MRI scanner. To measure exercise intensity, RPE and HR were recorded every 5 min. During the rest condition, participants were seated for 30 min while HR and RPE were measured every 5 min.

fMRI Acquisition

Whole-brain, event-related fMRI was conducted on a Siemens 3.0 Tesla MR scanner (Magnetom Trio Tim Syngo, Munich, Germany). A 32-channel head coil was used for radio frequency transmission and reception. Foam padding was positioned within the head coil to minimize head movement within the coil. A high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image was acquired for co-registration with the following sequence parameters: Magnetization Prepared Rapid Acquisition of Gradient Echo (MPRAGE), matrix= 256, field of view (FOV)=230 mm, voxel size=0.9×0.9× 0.9 mm, slices=192 (sagittal plane, acquired right to left), slice thickness=0.9 mm, repetition time (TR)=1900 ms, echo time (TE)=2.32 ms, inversion time (TI)=900 ms, flip angle=9°, and sequence duration=4:26 min.

The Famous Names Task (FNT) event-related data were acquired using the following sequence parameters: single-shot gradient echo planar images, matrix=64, FOV=192 mm, voxel size=3.0×3.0×3.0 mm, slices=36, slice thickness=3.0 mm, TR/TE=2000/24 ms, volumes=175, flip angle=70°, bandwidth=2232 Hz/Px, multi-slice mode=Interleaved, and sequence duration=5:56 min. The MPRAGE and FNT sequences began approximately 15 and 35 min after the completion of the exercise or rest session, respectively.

fMRI Task

Semantic memory activation was assessed using the FNT, presented electronically using E-Prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). The FNT was administered during fMRI acquisition following the exercise or rest condition. Participants were instructed to respond as accurately as possible to identify a set of Famous name stimuli. The fMRI task stimuli consisted of 30 names of easily recognized prominent entertainers, politicians, or sports figures obtained through magazines, trivia books, and the Internet (e.g., Ringo Starr) and 30 names of non-famous individuals chosen from a local phone book (Nielson et al., Reference Nielson, Douville, Seidenberg, Woodard, Miller, Franczak and Rao2006). Only names with a high rate of identification (>90% correct for targets and foils) were selected from an original pool of 784 names (Douville et al., Reference Douville, Woodard, Seidenberg, Miller, Leveroni, Nielson and Rao2005).

Stimuli were presented for 4 s each with randomly interspersed 4-s fixation intervals at an overall 2:1 (names:fixation) ratio. Fixation intervals consisted of a single centrally placed fixation crosshair. Participants were instructed to make a right index finger key press for Famous names and a right middle finger key press for Non-Famous names. Both accuracy (% correct) and response time (ms) were recorded. Upon arrival, participants underwent a practice session, which included 10 trials and lasted 1:15 min. The practice version was always different form the version used in the scanner. Moreover, two versions of the task, comprising unique sets of Famous-and Non-Famous names, were counterbalanced across experimental sessions.

fMRI Analysis

Preprocessing

Functional images were processed using the Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI) software package (Cox, Reference Cox1996). Using AFNI’s Dimon program, the DICOM image files were converted into 3D space. For each image time series, the scanner automatically discarded the first three TRs and, subsequently, two additional TRs were excluded to avoid magnetization disequilibrium. Slices within each volume of the time series were then time-shifted to the beginning of the TR. The time series were spatially registered to minimize the effect of head motion and aligned to the participant’s high-resolution anatomical image. The images then were transformed into standard stereotaxic space (AFNI’s MNI152_T1_2009c template) and spatially smoothed using a 4-mm Gaussian full-width half-maximum kernel. Incorrect trials were removed from the analysis. Then, regressors of interest for the presentation of Famous and Non-Famous name stimuli were created by convolving a square wave (duration (d)=4 s; amplitude (p)=1) with the default canonical hemodynamic response function in AFNI, and the Famous minus Non-Famous contrast was computed. The resulting parametric maps for each participant were submitted to the group analysis.

Whole brain voxel-wise analysis

Semantic memory-related activation maps (Famous minus Non-Famous) were created separately for the exercise (see Supplementary Figure S1) and rest (see Supplementary Figure S2) conditions to illustrate the intensity and spatial location of activation after each condition. AFNI’s 3dClustSim was used to control the whole brain family-wise error rate (FWER) at p<.01 by setting a voxel-wise probability threshold of p<.001 and minimum cluster size k≥26 (NN=1, bi-sided) (Eklund, Nichols, & Knutsson, Reference Eklund, Nichols and Knutsson2015). Semantic memory-related activation was defined where the Famous minus Non-Famous contrast was significantly different from zero at FWER corrected p<.01 (Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Durgerian, et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Verber, Durgerian and Lancaster2011; Woodard et al., Reference Woodard, Seidenberg, Nielson, Antuono, Guidotti, Durgerian and Rao2009).

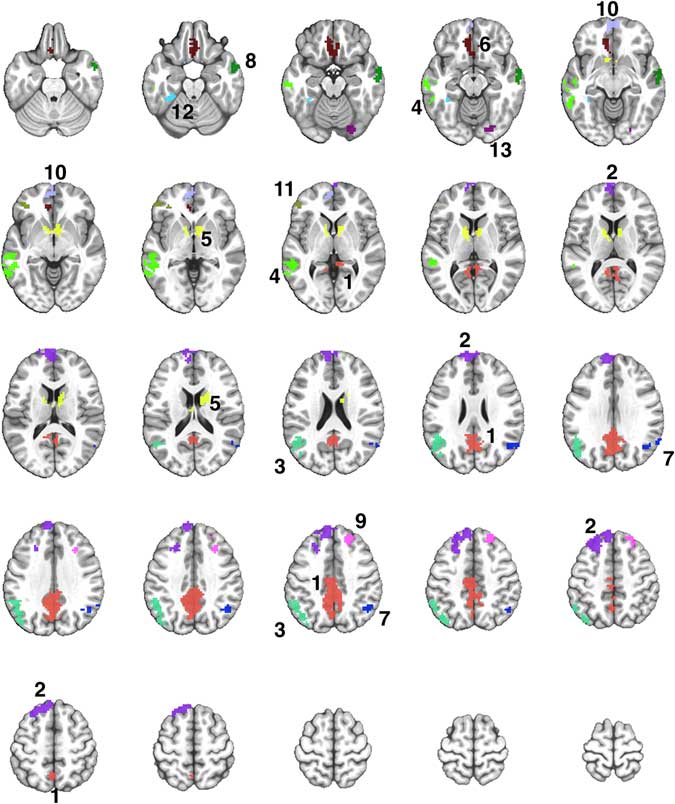

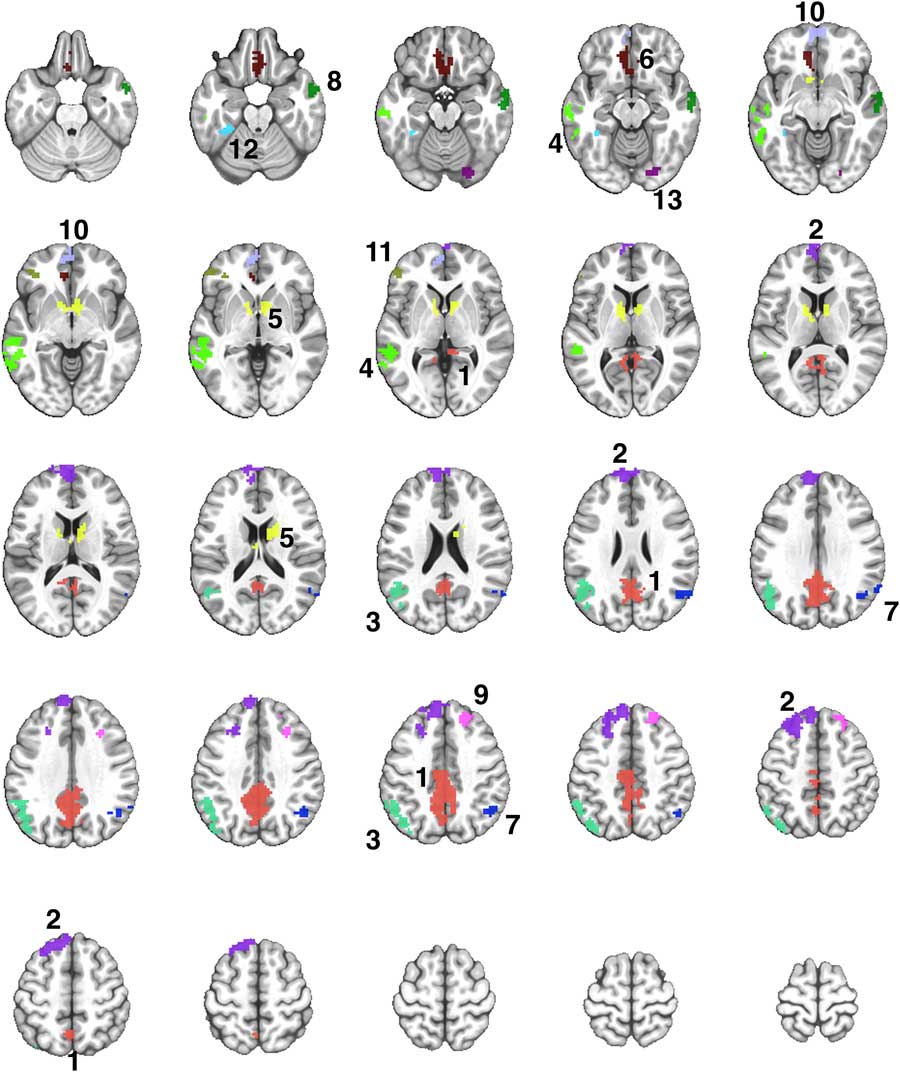

Using AFNI’s 3dcalc function, the activation maps for each condition were combined to create a disjunction (“OR”) mask (see Figure 2) by conjoining activated regions identified in the voxel-wise analysis for the exercise and rest conditions. Any significantly activated clusters in each condition, based on the Famous minus Non-Famous contrast, contributed to the disjunction map. Voxels identified in the disjunction map were applied as a mask to each participant’s individual data, and the mean activation intensities (β coefficients) for each participant within each distinct region were extracted for both the exercise and rest conditions. Finally, a one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the activation intensity between the exercise and rest conditions in each region, with statistical significance determined at p < .05.

Fig. 2 A montage of axial slices showing the 13 regions derived from a disjunction (OR) mask activated in both Exercise and Rest conditions. The numerical labels correspond to the region numbers shown in Table 3. The colors only denote the spatial location of the distinct regions, which may appear in multiple slices of the montage.

Hippocampal region of interest analysis

Using an anatomically defined region of interest, we examined the effect of acute exercise on semantic memory-related activation of the bilateral hippocampus. AFNI’s MNI reference dataset (MNI152_T1_2009c) was processed with FreeSurfer’s automated pipeline for generating cortical and subcortical volumetric reconstructions (Fischl, Reference Fischl2012). Using the Desikan-Killiany aparc + aseg segmentation, a structurally defined bilateral hippocampal mask was created based on the resulting FreeSurfer parcellation using AFNI’s 3dcalc. Using this mask, the mean β coefficients were extracted from each participant’s parametric maps for the exercise and rest conditions based on a whole brain FWER corrected threshold of p<.01 (voxel-wise probability threshold of p<.01 and minimum clusters of size k≥426 (NN=1, bi-sided), and the difference between exercise and rest was determined using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA (p<.05).

RESULTS

Participants

Based on the 7-day physical activity recall interview, our participants indicated regular participation in moderate intensity physical activity. Of the 32 participants who completed the entire study protocol, five participants were excluded from analysis due to technical errors with the button response box during the FNT task and one participant was excluded due to failed completion in one of the experimental sessions. The excluded participants were mostly women (66.7%), predominantly white (83.3%), and had similar age (66.7 ± 8.1 years), BMI (23.2), resting HR (66 bpm), and MMSE score (28.7). None of these demographic characteristics were statistically significantly different from the participants who completed the study.

Exercise Manipulation Check: HR, RPE, and fMRI Task Performance

HR and RPE data during exercise and rest conditions are reported in Table 2. HR (±SD) was significantly greater during the exercise (136.1 ± 18.4 bpm) compared to rest (66.3 ± 9.2 bpm) [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=331.44; p<.001; η2=0.930]. Similarly, RPE during exercise was significantly greater (14.5 ± 1.4) relative to rest (6.1 ± 0.4) [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=945.562; p<.001; η2=0.974]. The mean RPE value during exercise was most closely associated with the verbal anchor “Hard”, indicating that participants performed exercise at the prescribed subjective exertion level of moderate intensity.

Table 2 Exercise and fMRI task outcome data for study participants

Note: p-Values and effect sizes reflect between and within group differences. SD, standard deviation; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; HR, heart rate; BPM, beats per minute; RT, response time; ms, millisecond; percentage of heart rate reserve; η2 p, partial eta squared. Bold indicates p<.05.

During FNT performance (see Table 2), response time (RT) for Famous names (±SD) was 1141.1 ± 282.7 ms after exercise and 1148.2 ± 267.6 ms after rest. The mean RT (±SD) for Famous names did not show significant difference between the two conditions [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=0.083; p=.775; η2=0.0037]. The mean RT (±SD) for Non-Famous names was 1413.6 ± 363.4 ms after exercise and 1449.2 ± 267.6 ms after rest. The mean RT (±SD) for Non-Famous names also was not significantly different between the two conditions [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=0.656; p=.426; η2=0.026]. The mean performance accuracy for Famous names was not statistically different between exercise (88.3 ± 17.9%) and rest (89.4 ± 15.5%) [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=0.332; p=.570; η2=0.013]. The participants correctly identified greater than 92% of the Non-Famous names after both conditions and there was no significant condition main effect [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=0.001; p=.971; η2=0.000].

Semantic Memory fMRI Activation: Exercise and Rest Versus Zero

Results from the voxel-wise analysis and volumes of the regions that were activated in the comparison of Famous minus Non-Famous names after the exercise and rest conditions are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Although the spatial extent of activation did not include a statistical comparison between the exercise and rest conditions, exercise was associated with a greater extent of activation (2322 voxels; see Supplementary Figure S1) compared to rest (637 voxels; see Supplementary Figure S2).

Semantic Memory fMRI Activation: Comparisons of Exercise Versus Rest

The Famous > Non-Famous comparison resulted in 13 contiguous regions showing significant semantic processing-related activation after exercise or rest (Supplementary Table S1). Table 3 shows the locations of the 13 regions, and the results of the repeated measures ANOVA to compare the activation in each region after the exercise and rest conditions. Four of the 13 regions showed significantly greater activation after exercise compared to rest (see Figure 3).

Table 3 Comparison of semantic memory-related activation (Famous minus Non-Famous) between the exercise and rest conditions in 13 regions

Note: ROI, regions of interest; Positive, right (x), anterior (y), and superior (z), representing peak activation in Talairach coordinates; BA, Broadmann area; AG, angular gyrus; CN, Caudate nucleus, FG, fusiform gyrus; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; IPL, inferior parietal lobule; LG, lingual gyrus; LN, Lentiform nucleus; MEFG, medial frontal gyrus; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; RG, rectal gyrus; SCG, subcallosal gyrus; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; vox, number of voxels in mm3; SD, standard deviation. Comparisons in bold font are significant at p<.05.

Fig. 3 Mean semantic memory-related activation intensity (mean β coefficient) for regions demonstrating significant differences between the exercise and rest conditions (*** significant difference at p<.0001, ** significant difference at p<.01, * significant difference at p<.05). Note. ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; FG, fusiform gyrus; MFG, middle frontal gyrus. Error bars=SEM.

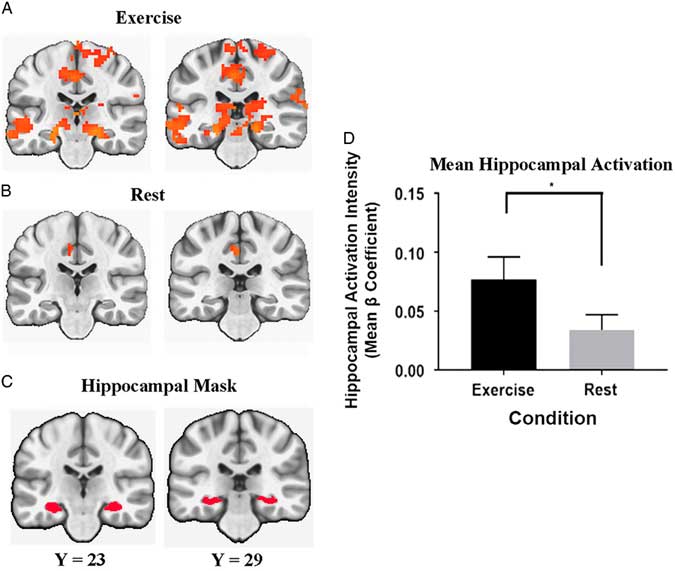

In the a priori hippocampal activation analysis, the mean semantic memory-related activation in the bilateral hippocampus was significantly greater after exercise compared to after rest [Condition main effect, F(1,25)=5.382; p=.02; η2=0.177]. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison between the conditions in the bilateral hippocampus.

Fig. 4 Coronal view of regions that include the hippocampal formation. Significant semantic memory-related activation (Famous minus Non-Famous) was determined at a whole brain FWER corrected threshold of p<.01 after the exercise (A) and rest (B) conditions. The anatomical bilateral hippocampal mask is presented in panel (C). The bar graph (D) represents the bilateral hippocampal activation intensity (Mean beta Coefficient) differences between exercise and rest conditions (* significant difference at p<.05).

DISCUSSION

The fMRI results provide evidence that an acute bout of aerobic exercise can influence semantic memory neural circuits in healthy older adults. Specifically, we have shown greater semantic memory activation following a single session of exercise compared to rest in several brain regions involved in semantic memory retrieval. These effects were localized to the known semantic memory network, and thus do not appear to reflect an overall or general increase in brain blood flow.

The present results were contrary to the hypothesis of reduced semantic memory activation. To address this discrepancy, possible neurophysiological evidence underlying the effects of acute exercise on cognition and brain function needs to be examined. One of the important questions pertinent to the study is how acute exercise yielded greater semantic memory activation compared to seated rest. Although the physiological mechanism behind acute exercise and associated enhancement in cognitive function remains unidentified, a plausible candidate is the upregulation of brain dopamine and noradrenaline through exercise (McMorris, Collard, Corbett, Dicks, & Swain, Reference McMorris, Collard, Corbett, Dicks and Swain2008).

The upregulation of brain dopamine and noradrenaline are associated with stimulated transcription, expression of neural growth factors [e.g., brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)], and neurogenesis particularly in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampal regions (Intlekofer & Cotman, Reference Intlekofer and Cotman2013; Trejo, Carro, & Torres-Aleman, Reference Trejo, Carro and Torres-Aleman2001; Van Praag, Shubert, Zhao, & Gage, Reference Van Praag, Shubert, Zhao and Gage2005). Acute upregulations in these neurophysiological pathways are associated with improved cognitive function (McMorris et al., Reference McMorris, Collard, Corbett, Dicks and Swain2008). Although the current study did not assess the metabolism of such neurotransmitters, it is possible that upregulation of dopaminergic and/or noradrenergic neurotransmitters in the brain elicited by a single bout of exercise (Hyodo et al., Reference Hyodo, Dan, Suwabe, Kyutoku, Yamada, Akahori and Soya2012) resulted in greater semantic memory-related activation compared to rest.

The scaffolding theory of aging and cognition (STAC) theory suggests that the greater neural activation during memory retrieval in cognitively intact older adults may reflect neural reserve or successful compensation (Reuter-Lorenz & Park, Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014). Previous cross-sectional (Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Verber, et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Durgerian, Antuono and Rao2011) and longitudinal evidence (Woodard et al., Reference Woodard, Sugarman, Nielson, Smith, Seidenberg, Durgerian and Rao2012) support the idea that greater extent and intensity of fMRI activation during the FNT is associated with cognitive stability over time. Taken together, the current findings suggest that acute exercise promotes engagement in the extended semantic memory networks and the greater engagement may reflect enhanced cognitive function in healthy older adults.

Another question left to address is why acute exercise and long-term exercise interventions result in inconsistent semantic memory activation patterns. We speculated that performing a 30-min session of aerobic exercise would engender reduction in semantic memory activation. Our prediction was based on a 12-week walking exercise intervention study demonstrating that increased maximal aerobic capacity following the intervention led to an associated enhanced neural efficiency through a decreased neural workload during successful engagement of semantic memory networks (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013).

Because the adaptations to chronic exercise training arise from an accumulation of acute exercise-induced effects, we hypothesized that performing acute exercise would also reduce semantic memory activation. However, the current and previous results may support the conclusion that short-term and long-term exercise may affect semantic memory activation differently. Cabeza (Reference Cabeza2002) suggested that greater activation patterns after a single session of exercise may demonstrate the occurrence of HAROLD (Hemispheric Asymmetry Reduction in Older Adults), presumably reflecting the activity of compensatory neural networks when performing cognitive tasks.

Recruiting a more extensive neural network during successful engagement in a cognitive task indicates a possible stimulus for enhancement or reserve in cognitive function elicited by acute exercise (Hyodo et al., Reference Hyodo, Dan, Suwabe, Kyutoku, Yamada, Akahori and Soya2012). The enhancement in neural network engagement during successful semantic memory retrieval after long-term participation in exercise may be indicated by reduced fMRI activation, suggesting reduced neural workload and greater network efficiency. The results of the current study complement the previously published study by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013) and suggest that both acute and chronic exercise may differentially benefit the semantic memory networks.

Famous name task considerations

The present study used a low effort and high accuracy semantic memory task which instructs participants to discriminate between Famous and Non-Famous names (Douville et al., Reference Douville, Woodard, Seidenberg, Miller, Leveroni, Nielson and Rao2005). Hantke et al. (Reference Hantke, Nielson, Woodard, Breting, Butts, Seidenberg and Rao2013) suggested that semantic memory fMRI activation may be a better predictor of longitudinal cognitive change than episodic memory-related activation, while other groups of researchers have shown that future cognitive decline can be predicted by fMRI activation during episodic memory tasks (Bookheimer et al., Reference Bookheimer, Strojwas, Cohen, Saunders, Pericak-Vance, Mazziotta and Small2000; O’brien et al., Reference O’Brien, O’Keefe, LaViolette, DeLuca, Blacker, Dickerson and Sperling2010). The FNT we have used has two major advantages over episodic memory tasks.

First, the FNT has been designed to be inherently easy to perform, and, therefore, results in high accuracy even without practice. Several previous studies using the FNT in a wide range of participants including older and younger adults (Douville et al., Reference Douville, Woodard, Seidenberg, Miller, Leveroni, Nielson and Rao2005; Nielson et al., Reference Nielson, Douville, Seidenberg, Woodard, Miller, Franczak and Rao2006), individuals with high risk for Alzheimer’s disease (Seidenberg et al., Reference Seidenberg, Guidotti, Nielson, Woodard, Durgerian, Antuono and Rao2009; Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Durgerian, et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Verber, Durgerian and Lancaster2011) and those diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013; Woodard et al., Reference Woodard, Seidenberg, Nielson, Antuono, Guidotti, Durgerian and Rao2009) show consistently high accuracy (>80%) on the task. Because the task is so easy to perform, we did not expect participants to improve their behavioral performance. Participants in the present study also demonstrated high accuracy (>88%) during recognition of famous names. The high accuracy rate, in fact, is a major advantage of the task as it eliminates any confounding influence of task difficulty. Unlike more difficult episodic memory tasks, for example, the activation observed in this semantic memory task is independent of task performance and task difficulty.

Second, the event-related fMRI design allows the exclusion of incorrect trials and thus only successful memory trials are used for the analysis (Seidenberg et al., Reference Seidenberg, Kay, Woodard, Nielson, Smith, Kandah and Rao2013). The use of an event-related procedure may have reduced error-based contributions to the functional maps (Woodard et al., Reference Woodard, Seidenberg, Nielson, Antuono, Guidotti, Durgerian and Rao2009). Also, by subtracting the Non-Famous names activation from that of Famous ones, we were able to remove any confounding influence of performance and any activation not related to semantic memory network (e.g., activations of visual cortex when seeing the screen or motor cortex associated with finger movement during performance of the task). This allows for the isolation of semantic memory-related activation, as demonstrated previously by others (Douville et al., Reference Douville, Woodard, Seidenberg, Miller, Leveroni, Nielson and Rao2005; Nielson et al., Reference Nielson, Douville, Seidenberg, Woodard, Miller, Franczak and Rao2006; Seidenberg et al., Reference Seidenberg, Guidotti, Nielson, Woodard, Durgerian, Antuono and Rao2009; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013; Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Durgerian, et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Woodard, Seidenberg, Verber, Durgerian and Lancaster2011; Sugarman et al., Reference Sugarman, Woodard, Nielson, Seidenberg, Smith, Durgerian and Rao2012; Woodard et al., Reference Woodard, Seidenberg, Nielson, Antuono, Guidotti, Durgerian and Rao2009).

One may wonder if the effects we observed could be explained by increased cerebral blood flow (CBF) after exercise. Studies in humans have demonstrated that global brain blood flow is controlled quite tightly during exercise, and is maintained at a nearly constant rate not different from a resting metabolic rate (Ide & Secher, Reference Ide and Secher2000). The key question is whether or not there are regional changes in CBF after acute exercise in areas implicated in semantic memory (or other cognitive functions). Studies that have measured CBF after exercise have reported mixed results; exercise has been shown to increase global CBF (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paulson, Cook, Verber and Tian2010), to decrease CBF (MacIntosh et al., Reference MacIntosh, Crane, Sage, Rajab, Donahue, McIlroy and Middleton2014), and to not change CBF (Pontifex, Gwizdala, Weng, Zhu, & Voss, Reference Pontifex, Gwizdala, Weng, Zhu and Voss2018).

Unfortunately, we do not have the perfusion imaging data to directly address the question regarding regional changes in CBF. However, the experimental design of the FNT takes into consideration global changes in CBF through the subtraction of the BOLD response for the Famous and Non-Famous names as the estimate of neural activation. If exercise had a general effect to increase CBF throughout the brain (or even regionally), then this would have affected the BOLD signal in response to the Famous and Non-Famous name stimuli; their subtraction effectively cancels any effect related to whole brain differences in CBF. Therefore, it is unlikely that increased CBF after acute exercise can explain the results of present study.

Moreover, the pattern of activation after both conditions is very consistent with several papers we have published over the past 10 years using this task (Nielson et al., Reference Nielson, Douville, Seidenberg, Woodard, Miller, Franczak and Rao2006; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013; Woodard et al., Reference Woodard, Seidenberg, Nielson, Antuono, Guidotti, Durgerian and Rao2009), and is localized in the well-characterized semantic memory network (Binder, Desai, Graves, & Conant, Reference Binder, Desai, Graves and Conant2009; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Bonner-Jackson, Nielson, Seidenberg, Smith, Woodard and Durgerian2015), including the bilateral middle temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, and precuneus.

Because of the well-documented effects of exercise on the hippocampus, we also conducted an a priori analysis using a hippocampal anatomical mask and identified greater bilateral activation after exercise compared to rest. Regular participation in physical activity and associated enhancement in cardiorespiratory fitness are related to attenuation of age-related brain tissue atrophy, especially within the hippocampus (Colcombe et al., Reference Colcombe, Erickson, Scalf, Kim, Prakash, McAuley and Kramer2006; Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Prakash, Voss, Chaddock, Heo and McLaren2010; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Rykhlevskaia, Brumback, Lee, Elavsky, Konopack and Gratton2008; Suwabe et al., Reference Suwabe, Byun, Hyodo, Reagh, Roberts, Matsushita and Suzuki2018).

Also, regular exercise has been shown to decrease amyloid burden in the hippocampus (Adlard et al., Reference Adlard, Perreau, Pop and Cotman2005). The recent work by Suwabe and colleagues (Suwabe et al., Reference Suwabe, Byun, Hyodo, Reagh, Roberts, Matsushita and Suzuki2018) suggests low intensity exercise is sufficient to increase hippocampal activation during pattern separation. Our findings further suggest that acute moderate intensity exercise, compared to rest, results in a greater recruitment of hippocampal neural activation during semantic memory retrieval.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations in the current study. First, the present study did not differentiate types or intensities of exercise, or determine if acute exercise influences other cognitive domains. An important direction for future research is to investigate the effect of acute exercise of differing intensities on other cognitive domains including executive function using the fMRI BOLD signal. Second, this study is not able to answer questions regarding the effect of acute exercise on older adults diagnosed with neurodegenerative symptoms such as mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, since only cognitively asymptomatic older adults participated in this study. Similarly, our participants were regularly engaged in moderate intensity physical activity, and we cannot assume these effects would be observed in sedentary older adults.

In addition, because the FNT task engages semantic memory networks and is designed to be inherently easy to perform, our study was not designed to examine changes in other types of memory performance, such as episodic memory or working memory. Finally, due to time and cost constraints, we were not able to conduct scans both before and after the rest and exercise conditions. However, using our counterbalanced post-test only design, we were able to demonstrate that HR and perception of effort were significantly greater during the exercise session compared to rest, indicating a sound experimental manipulation.

CONCLUSION

The present study suggests that an acute bout of exercise is associated with an increase in semantic memory activation compared to rest when measured approximately 30 min after the exercise has ended. Our previous study (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013) showed that exercise training was associated with decreased semantic activation using the same task on a day that exercise was not performed. The decreased activation after a period of exercise training, coupled with consistently high accuracy on the task, suggests enhanced neural efficiency (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Nielson, Antuono, Lyons, Hanson, Butts and Verber2013).

Our current results show an opposite pattern. We speculate that performing a single bout of exercise elicits a short-term impact on the upregulation and expression of neurotransmitters and neural growth factors that promotes increased neural activation (Hyodo et al., Reference Hyodo, Dan, Suwabe, Kyutoku, Yamada, Akahori and Soya2012). With regular participation in exercise, this process repeatedly occurs; a stress to the system followed by recovery and adaptation. This may promote a greater capacity within the neural networks, perhaps related to increased oxidative capacity, mitochondrial function, insulin sensitivity (Heath et al., Reference Heath, Gavin, Hinderliter, Hagberg, Bloomfield and Holloszy1983), and/or neurotransmitter receptor number or sensitivity (Meeusen et al., Reference Meeusen, Smolders, Sarre, De Meirleir, Keizer, Serneels and Michotte1997).

Exercise results in increased dopaminergic activity in the basal ganglia, and these ascending dopaminergic projections have been shown to increase the signal to noise ratio in frontal cortical networks, and D1 receptor activation may help to prolong frontal-striatal network activation (Crosson, Benjamin, & Levy, Reference Crosson, Benjamin and Levy2007). These adaptations may represent the building of a stronger neural scaffolding (Reuter-Lorenz & Park, Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014) that ultimately leads to a stronger, more efficient and resilient neural network, able to better withstand age- or disease-related insults.

Based on this plausible mechanism, we hypothesize that neural adaptations after daily bouts of exercise mediate exercise training-related cognitive improvement and enhanced brain function. The immediate and long-term clinical impacts of these findings are yet to be fully elucidated, but our data suggest that single sessions of exercise may be a stimulus to bolster the capacity of memory networks during successful memory retrieval, and support previous findings indicating exercise offers protection against age-related cognitive decline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to report. Support for this study was provided by the Department of Kinesiology at University of Maryland. This project was completed by J.W. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Kinesiology at the University of Maryland. We thank the participants for their time and dedication while participating in this study. We also thank Sally Durgerian for her technical and analytical assistance.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617719000171