Although the vast majority of Americans decide to have children (or more children) because they anticipate that parenthood will be personally fulfilling (Bloom Reference Bloom2021; Hansen Reference Hansen2012), there have been and remain other more instrumental reasons to procreate. Indeed, historically, physical protection, support in old age, tribal survival, the preservation of family wealth, political alliances, and social honor were the major reasons to have children (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021; Schoen et al. Reference Schoen, Kim, Nathanson, Fields and Astone1997). Given that these latter reasons no longer exercise the same fertility pressure in wealthy Western societies, this study considers what undergirds support for “group-serving pronatalism” in the contemporary United States. Specifically, what drives certain groups of Americans to consider group-serving reasons like bolstering national fertility rates, perpetuating one’s religious or racial heritage, or securing political power as important reasons to have children, even after accounting for the personal fulfillment they attribute to parenthood?

Previous research would lead us to expect group-serving pronatalism to be stronger among religious and political conservatives. Both pronatalist cultural values and practices are traditionally higher among these Americans and their communities (Hayford and Morgan Reference Hayford and Morgan2008; Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021; Perry and Schleifer Reference Perry and Schleifer2019; Schnabel Reference Schnabel2021; Vogl and Freese Reference Vogl and Freese2020). Moreover, contemporary leaders on the religious and political right often laud having children as a way of addressing national economic woes and issues of religious and political influence or even racial survival (Del Valle Reference Del Valle2024; Martuscelli Reference Martuscelli2023). Prominent Christian pastors and authors, as well as far-right provocateurs, for example, have argued that conservative Christians should have more babies to win “the culture war” (DeYoung Reference DeYoung2020), “save our civilization” (Walsh Reference Walsh2021), and stave off “the great replacement” (Del Valle Reference Del Valle2024; Keenan Reference Keenan2024).

Related to this last point, recent research by Perry, McElroy, et al. (Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022) found that Christian nationalist ideology—reflecting a desire to restore or privilege conservative Christian values and identity in American civic life—is among the leading factors supporting what they call “nationalist pronatalism.” Yet their measures only tap into broader pronatalist attitudes related to concerns about the nation’s declining fertility, women delaying motherhood, a selfish anti-children culture, and married couples needing to have more babies, not fewer. In other words, their questions do not ask for specific reasons to have children—for example, for the nation or for one’s religious, racial, or political group—and thus cannot directly assess the link between Christian nationalism and whether such reasons might indeed be group-serving.

Drawing on representative data that include explicit questions about specific group-serving reasons to have children and use two measures of Christian nationalism to ensure robustness, we examine the association between Christian nationalism and group-serving pronatalism in general and for specific reasons. We also test how this association may be moderated by key social identities and relevant ideological commitments.

BACKGROUND AND EXPECTATIONS

Research suggests that a variety of ideological and identity-based influences might incline Americans on the political and religious right to endorse “pronatalism,” most often meaning an explicit belief or informal norm that children are a source of individual and cultural flourishing and thus families should have more (Perry Reference Perry2017; Wilde Reference Wilde2020). Within and across societies, religious commitment and theological conservatism are associated with higher fertility. In some cases, this is because of explicit doctrinal proscriptions against birth control (Wilde Reference Wilde2020). However, higher fertility largely occurs because conservative religiosity is associated with greater social traditionalism and lower educational attainment (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021; Schnabel Reference Schnabel2021). Vogl and Freese (Reference Vogl and Freese2020) have shown that “family values” conservatives tend to have more siblings and more children, which is also related to their being more religious and less educated. The authors demonstrate that the relatively higher fertility of family-values conservatives bolsters their political influence, with opposition to same-sex marriage and abortion in the United States remaining substantially higher than if their fertility rates were equal to those of other Americans.

This latter point raises an often ignored dynamic at play in ideological pronatalism; namely, that higher fertility benefits group interests. Historically, group interests such as economic and military support were major reasons to have children (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2021; Schoen et al. Reference Schoen, Kim, Nathanson, Fields and Astone1997). Yet pronatalism is still championed on the American right with an eye toward how it protects religious, racial, national, and partisan interests. Evangelical megachurch pastor and author Kevin DeYoung (Reference DeYoung2020) cited declining overall birthrates and told evangelicals, “Here’s a culture war strategy conservative Christians should get behind: have more children and disciple them like crazy.… The future belongs to the fecund.” More recently, Christian social media provocateur and pseudonymous writer for the Claremont Institute, “Peachy Keenan” (Reference Keenan2024) likewise cited the higher fertility of conservative Christians as a sign of hope: “Trads, Christians, Catholics, and other baby-friendly types on the Right are still leaning into parenthood and big families. The libs are staying childfree.… They’re wiping out their own genetic lines on purpose!”

Historically, group interests such as economic and military support were major reasons to have children. Yet pronatalism is still championed on the American right with an eye toward how it protects religious, racial, national, and partisan interests.

These calls explicitly assert that fertility preserves the cultural and political influence of conservative Christians. Yet the racial implications are clear, given that such calls are almost certainly not intended to encourage the higher fertility of committed Christians who largely vote for Democrats, such as Black Protestants and Latino Catholics. Among other conservative voices, the racialist implications of pronatalism are more explicit. Christian-right activists like Charlie Kirk (Reference Kirk2020), former Fox News host Tucker Carlson (Bort Reference Bort2021), and Peachy Keenan (Reference Keenan2024) have all publicly lamented America’s “fertility crisis” and stressed that the alternative to (White) native-born Americans replacing themselves will be economic and political “replacement” with Latino immigrants. Indeed, Keenan (Reference Keenan2024) celebrates the fact that taboos against saying “White genocide is real” and “Great replacement is not a conspiracy theory” are losing their power.

Still others cite national interests as the major reason to encourage more children. For example, given that economic vitality and social safety nets depend on a growing workforce and tax base, commentators argue that encouraging higher fertility is in the nation’s best interests and indeed worth subsidizing with policy (Del Valle Reference Del Valle2024; Last Reference Last2013; Vesoulis Reference Vesoulis2023). Others are more explicitly nationalistic, citing that higher fertility would encourage greater patriotism. For example, Christian-right provocateur Matt Walsh (Reference Walsh2021) on his podcast argued that people with more children are less selfish and more connected to community and country.

We propose that Christian nationalism ties together much of the ideological foundation undergirding calls for group-serving pronatalism in the United States. Gorski and Perry (Reference Gorski and Perry2022) argue that (White) Christian nationalism represents a form of authoritarian “ethno-traditionalism” that conflates ethnoreligious identity with an understanding of national destiny and cultural supremacy; thus, it responds to perceived threats with calls to engagement. Indeed, recent experimental work has documented increases in Christian nationalism in response to perceptions of religious decline and replacement (Al-Kire et al. Reference Al-Kire, Pasek, Tsang and Rowatt2021; Walker and Haider-Markel Reference Walker and Haider-Markel2024). Although institutionalizing and preserving conservative Christian supremacy can take place at the policy level, calls by DeYoung, Keenan, and others support the idea that prioritizing religious, racial, national, or political group interests in decisions about childbearing would be another means to that end.

Although our focus is the United States, we can perceive these dynamics elsewhere throughout history and in the present day. Ethnonationalist (typically far-right) regimes around the world have long sought to bolster the cultural and political supremacy of those who traditionally held power via higher fertility (Perry, McElroy, et al. Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022; Wilde Reference Wilde2020). In the present day, Vladimir Putin in Russia and Viktor Orban in Hungary have both explicitly sought to encourage larger families to stave off cultural change caused by immigration. Each are held up as exemplars of strong leadership by the Christian far right in the United States because of their opposition to LGBT freedoms and their defense of national Christian identity (Gessen Reference Gessen2017; Martuscelli Reference Martuscelli2023; Perry, McElroy, et al. Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022). Most recently, Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni, who also espouses Christian nationalist views and advocates “great replacement” theory, has sought to “initiate a substantive cultural change” to bolster Italian fertility (Martuscelli Reference Martuscelli2023; Pascale Reference Pascale2023; Vergara Reference Vergara2022).

In summary, pronatalism is historically tied to religious conservatism, but group-serving pronatalism is often tied to political and ethnocultural threats in a zero-sum “us vs. them” paradigm (Del Valle Reference Del Valle2024). Because Christian nationalism, at bottom, represents adherence to a mythological understanding of whom the nation rightfully belongs to and a vision for establishing the supremacy of that group (Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023; Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022), we anticipate that Christian nationalism will powerfully predict group-serving pronatalism represented in a variety of reasons relevant to group supremacy, including the nation itself, one’s religious or racial group, and one’s political regime. Moreover, we anticipate that this influence goes above and beyond a commitment to partisan or ideological conservatism or traditionalism, or even to children as a means of personal fulfillment: rather, it represents a commitment to group supremacy that envisions childbearing as a promising means of preserving that supremacy.

Because Christian nationalism, at bottom, represents adherence to a mythological understanding of who the nation rightfully belongs to and a vision for establishing the supremacy of that group, we anticipate Christian nationalism will powerfully predict group-serving pronatalism represented in a variety of reasons relevant to group supremacy, including the nation itself, one’s religious or racial group, and one’s political regime.

In terms of potential moderating influences, Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey (Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023) argue that Christian nationalism represents “a Republican project” and, along with other studies, show that Christian nationalism’s influence often matters more for Americans on the partisan or ideological left, rather than those on the right (McDaniel, Nooruddin, and Shortle Reference McDaniel, Nooruddin and Shortle2022; Perry, Davis, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Davis and Grubbs2023). In addition to this, and following the same logic, we would also anticipate that Christian nationalism would matter at lower levels of social traditionalism. Other studies suggest that social factors like race and (less often) gender can moderate Christian nationalism’s influence (Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022; Perry, McElroy et al. Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022: Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2022). Importantly, Perry, McElroy, et al. (Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022) find that the association between Christian nationalism and “nationalist pronatalism” is stronger among men and is virtually nonexistent among Black Americans. Thus, we would anticipate a similar moderating influence regarding group-serving pronatalism.

METHODS

Data

Data for this study come from Waves 1, 3, and 4 of the National Addiction and Social Attitudes Survey (NASAS), which we designed (Perry, Davis, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Davis and Grubbs2023; Perry, Grubbs, and Schleifer Reference Perry, Grubbs and Schleifer2024). It was fielded in by YouGov, an international research data and analytics company. Wave 1 was fielded in March 2022, Wave 3 in October 2022, and Wave 4 in March 2023. Waves 1, 3, and 4 are the source of our control variables. Waves 3 and 4 supply two Christian nationalism measures, and Wave 4 provides a measure of fulfillment-driven pronatalism and measures for our outcome variable, group-driven pronatalism.

YouGov recruits a panel of respondents through websites and banner ads, which invite respondents to enter into lotteries for monetary prizes. To draw a nationally representative sample, YouGov uses a method called “matching.” Drawing a random sample from the American Community Survey, YouGov then matches a respondent in the opt-in panel who is the closest to the sensus respondent based on key sociodemographic factors. Because of the specific recruitment and sampling design used by YouGov, the company does not publish traditional response rates. However, it develops sampling weights to ensure that the survey sample is in line with nationally representative norms for age, gender, race, education, and census region. The resulting Wave 1 March 2022 survey sample included 2,809 Americans who were matched and weighted. Our final analytic sample in the full models is 1,486 cases after attrition and a modest number of missing cases.

Group-Serving Pronatalism

In Wave 4 of the NASAS, we asked Americans, “Which of the following are good reasons to have children?” The reasons included (1) Because you want to help reverse our nation’s declining fertilityFootnote 1; (2) Because you want to perpetuate your religious heritage; (3) Because you want to perpetuate your ethnic or racial heritage; and (4) Because you want to secure influence for those who share your political views. Response options ranged from 1 = Very bad reason to 5 = Very good reason. The questions correlate strongly, and confirmatory factor analyses reveal they load cleanly onto a single factor (see online appendix table A1). Thus, for our main outcome we combined them into an additive index with a Cronbach’s alpha of .88 indicating strong reliability. We also tested models with measures separated to ensure that key associations are not isolated to one or two measures. For all models we used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression.

Christian Nationalism Measures

Our primary independent variable of interest is Christian nationalism. As the literature on Christian nationalism has grown, several measurements have been used (Braunstein and Taylor Reference Braunstein and Taylor2017; Davis and Perry Reference Davis and Perry2021; Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023; Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022; McDaniel, Nooruddin, and Shortle Reference McDaniel, Nooruddin and Shortle2022; Vegter et al. Reference Vegter, Lewis and Bolin2023). Because we want to ensure that our findings are not limited to a specific way of measuring Christian nationalism, we use two composite indexes pulled from Waves 3 and 4 of the NASAS, respectively. See online appendix tables A2 and A3 for results of the factor analyses.

Both Christian nationalism measures from Waves 3 and 4 include the following four statements that have been used separately or in some combination in multiple studies (Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023; Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022; Perry, Grubbs, and Schleifer Reference Perry, Grubbs and Schleifer2024): (1) “America holds a special place in God’s plan”; (2) “The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation”; (3) “I consider founding documents like the Declaration of Independence and US Constitution to be divinely inspired”; and (4) “I consider being a Christian an important aspect of being truly American.” Responses ranged from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree.

For Wave 3, respondents were also asked how well the term “Christian nationalist” described them (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very well) to help us understand how affirming Christian nationalist views corresponded to actual identification with the label “Christian nationalism” (Pew Research Center 2024). These five measures together combine for a Cronbach’s alpha of .91 and thus create a reliable index of Christian nationalism (range 0–20).

In Wave 4, we replaced the single-item identity measure from Wave 3 with two additional statements to capture a “dominionist” dynamic described in other studies (e.g., Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023): (5) “Christians have a responsibility to gain control over national institutions like government, education, and the media” and (6) “The Bible should be the foundation of our legal system.” These two statements combine with the original four for a Cronbach’s alpha of .94 and thus create a reliable index of Christian nationalism (range 0–24).

Other Key Predictors

Other key predictors include factors that we theorize would be strongly associated with both group-serving pronatalism and Christian nationalism. These include measures of fulfillment-driven pronatalism, social traditionalism, and ideological and partisan conservatism. Along with questions about group-serving pronatalism, respondents were asked about the following reason to have children: “Because you find parenthood personally fulfilling.” Response options ranged from 1 = Very bad reason to 5 = Very good reason. We consider this an indicator of fulfillment-driven pronatalism that allows us to control for the degree to which respondents are already disposed to favor having more children as a personal preference.

We also sought to include a measure of social traditionalism to ensure that our Christian nationalism measures are tapping not only a preference for traditionalist social arrangements but also a desire for institutionalizing conservative Christian supremacy. In Wave 3, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) with the following statements: (1) I would support the Supreme Court overturning their 2015 decision that legalized same-sex marriages; (2) I would support legally nullifying all current same-sex marriages; (3) I support the 2022 Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade; and (4) I would support state governments arresting women who have abortions. The Cronbach’s alpha for these measures is reliable at .86, and thus we create an index set to zero (ranging 0–16). See online appendix table A4 for results from the factor analyses.

Lastly, we must ensure that Christian nationalism is not merely a proxy for political or religious conservatism/commitment generally. Christian nationalism is strongly related to conservative ideological identity and Republican partisanship (Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023; Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022), and thus we control for both. Respondents indicated their ideological identity from 1 = Very liberal to 5 = Very conservative, with 3 = Moderate. Likewise, our measure of partisanship ranges from 1 = Strong Democrat to 5 = Strong Republican, with 3 = Independent/Other.

Religious characteristics include measures of religious identity and commitment. Religious identity was measured with the following categories: Evangelical Protestant (reference), Non-Evangelical Protestant, Catholic, Other Christian, Non-Christian Religion, Atheist, Agnostic, and Nothing in Particular.Footnote 2 We also include a measure for religiosity derived from three questions about religious service attendance (1 = Never to 6 = More than once a week), prayer frequency (1 = Never to 7 = Several times a day), and religious importance (1 = Not at all important to 4 = Very important). We transformed measures into z-scores and combined them to create a religiosity index (alpha = .83). Online appendix table A5 presents results from the factor analyses for this measure.

Controls

Our multivariate regression analyses also include a variety of demographic controls. Age was measured in years from 20 to 97. Sex was measured with dummy-coded variables with men (reference), women, and nonbinary persons. Similarly, racial identity was measured with dummy variables, with White (reference), Black, Hispanic, and Other Race. Educational attainment was measured with attainment categories from 1 = less than high school to 6 = postgraduate work. Household income is measured with a series of dummy variables, including less than $30K per year (reference), $30–60K, $60–100K, $100–200K, and $200K or more, and did not indicate income. We also included a control for living in the South. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analyses and for bivariate associations between predictors and our main outcome.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Note: NASAS, Wave 1–4 (N = 1,486).

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Plan of Analysis

We first note key bivariate associations in Table 1. Turning to regression analyses, we recoded all continuous or ordinal measures to range from 0 to 1 to make plotting marginal effects and comparisons more intuitive (see Table 1 for original and recoded descriptive statistics). Full regression models are presented in online appendix tables A7–A10. Figure 1 presents forest plots in which we present the association between each predictor variable and our index of group-serving pronatalism, focusing on our Christian nationalism measure from Wave 3 (left panel) and Wave 4 (right panel). Figure 2 presents forest plots for our key ideological predictors and our four specific group-serving pronatalism rationales, again providing plots for our Christian nationalism measure from Wave 3 (left panels) and Wave 4 (right panels). Finally, Figure 3 plots marginal effects from noteworthy interactions.

Figure 1 Marginal Effects of Each Variable Predicting Group-Centered Pronatalism

NASAS, Waves 1–4 (N = 1,486). Analyses from appendix table A7. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

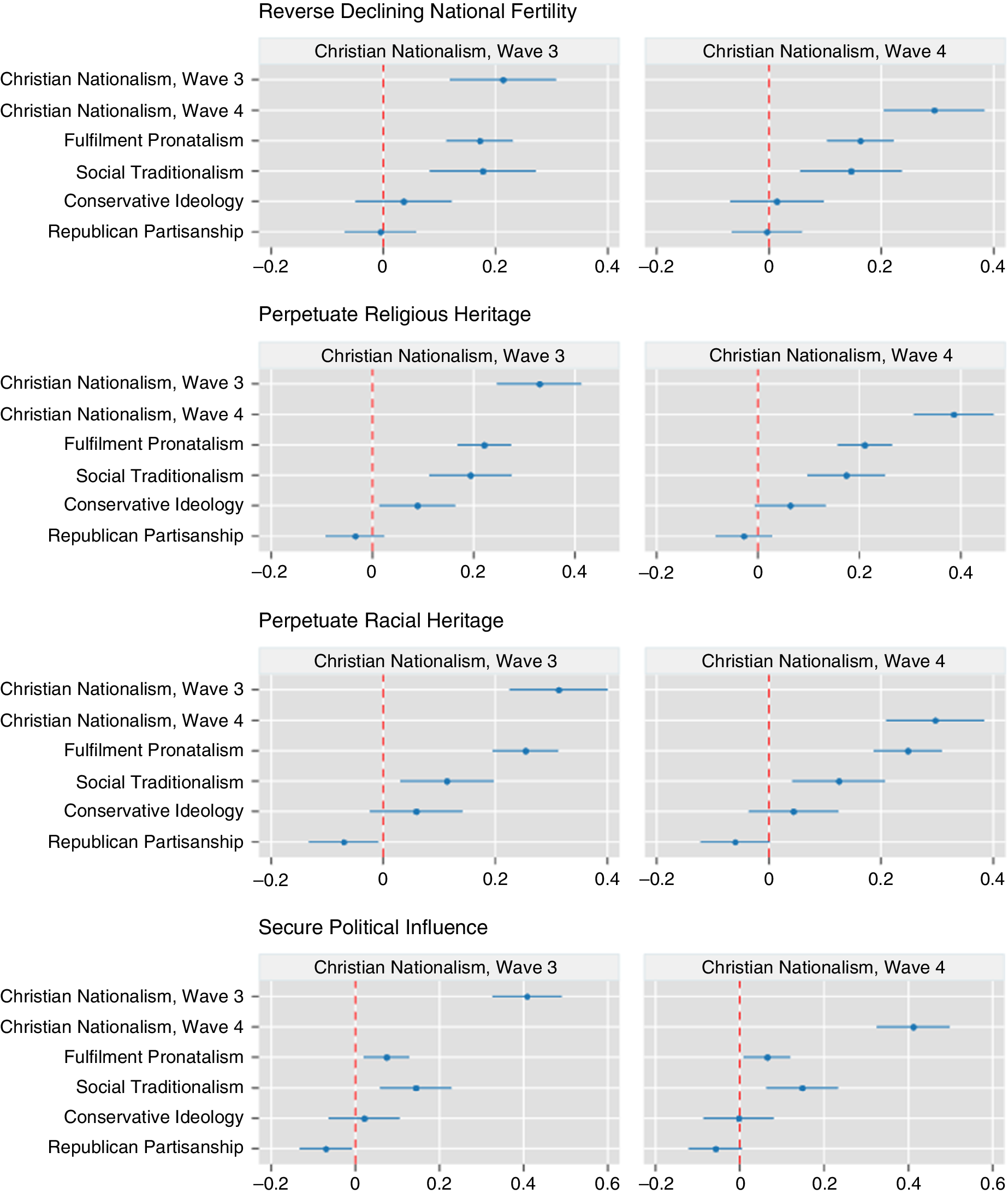

Figure 2 Marginal Effects of Key Variables Predicting Specific Pronatalist Rationales

NASAS, Waves 1–4 (N = 1,486). Analyses from appendix table A8. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS

At the bivariate level, either measure of Christian nationalism shows the strongest association with our focal outcome, the group-serving pronatalism index. In addition, Christian nationalism measures show the strongest association with the specific group-serving reasons for having children, when disaggregated (see online appendix table A6). As we would anticipate, social traditionalism is also strongly associated with group-serving pronatalism, as are personal religiosity, ideological conservatism, Republican partisanship, and fulfillment-driven pronatalism. Among other correlates, evangelical Protestants are the religious tradition most supportive of group-serving pronatalism, whereas atheists are the least. Because these key indicators of religious, ideological, and partisan conservatism are all strongly associated with one another (see online appendix table A6), we turn to multivariate analyses.

Figure 1 presents two forest plot panels demonstrating the association between our two Christian nationalism measures and other predictors with our measure of group-serving pronatalism (see online appendix table A7). Even after accounting for measures of ideological or partisan conservatism, social traditionalism, and how much Americans support having children as a means of personal fulfillment, either measure of Christian nationalism is positively associated with group-serving pronatalism. Indeed, the plots show either measure of Christian nationalism is the strongest predictor in the model (because all predictors were transformed to range from 0 to 1). Also positively associated with group-serving pronatalism are fulfillment-driven pronatalism and social traditionalism. Comparing these findings with the baseline model without Christian nationalism also shows that including Christian nationalism reduces the influence of both ideological conservatism and personal religiosity to nonsignificance (see online appendix table A7).

Interestingly, several non-evangelical religious traditions in Figure 1 appear significantly more likely than evangelicals to support group-serving pronatalism in full models. Yet bivariate associations (Table 1) indicate that evangelicals have the strongest positive association with this outcome. Ancillary analyses show that the signs flip and that non-evangelical religious traditions become significantly different from evangelicals when strong measures of ideological conservatism and traditionalism (Christian nationalism, social traditionalism) are included in models. These factors thus seem to account for any association between evangelical Protestants and group-serving pronatalist views.

Do these patterns reflect a strong association between Christian nationalism and only one or two of the group-serving reasons for having children included in our main outcome? Figure 2 shows forest plots for our main indicators of ideological conservatism and each of our four rationales separated (see online appendix table A8). Either measure of Christian nationalism has a significant positive association with all four group-serving reasons for having children.

Specifically, even after controlling for measures of social traditionalism, indicators of ideological and partisan conservatism, and Americans’ support for fulfillment-driven pronatalism, the more that Americans affirm Christian nationalist views, the more likely they are to say that having children to reverse the nation’s declining fertility rates, perpetuate one’s religious or racial heritage, or secure the influence of one’s political group are all good reasons to procreate. Indeed, either measure of Christian nationalism is far and away the strongest predictor of believing that having children to secure one’s political influence is a good reason to have them.

Yet, does the association between Christian nationalism (measured either way) and support for group-serving pronatalism depend on the values of some other key variables? To understand the potential influence of moderating factors, we tested several models with interaction effects (see online appendix tables A9 and A10). Ultimately, the models show that the interaction terms contribute little in terms of variance explained. Moreover, although some interaction terms reach statistical significance (particularly with the Wave 3 Christian nationalism measure), no interaction terms reach statistical significance at the .05 level for both measures of Christian nationalism. In addition, several that reach statistical significance show no meaningful difference when we plot out the marginal effects (e.g., see the interactions with ideological and partisan identity in online appendix A1 and A2, as well as the interactions with racial identity in online appendix figure A3).

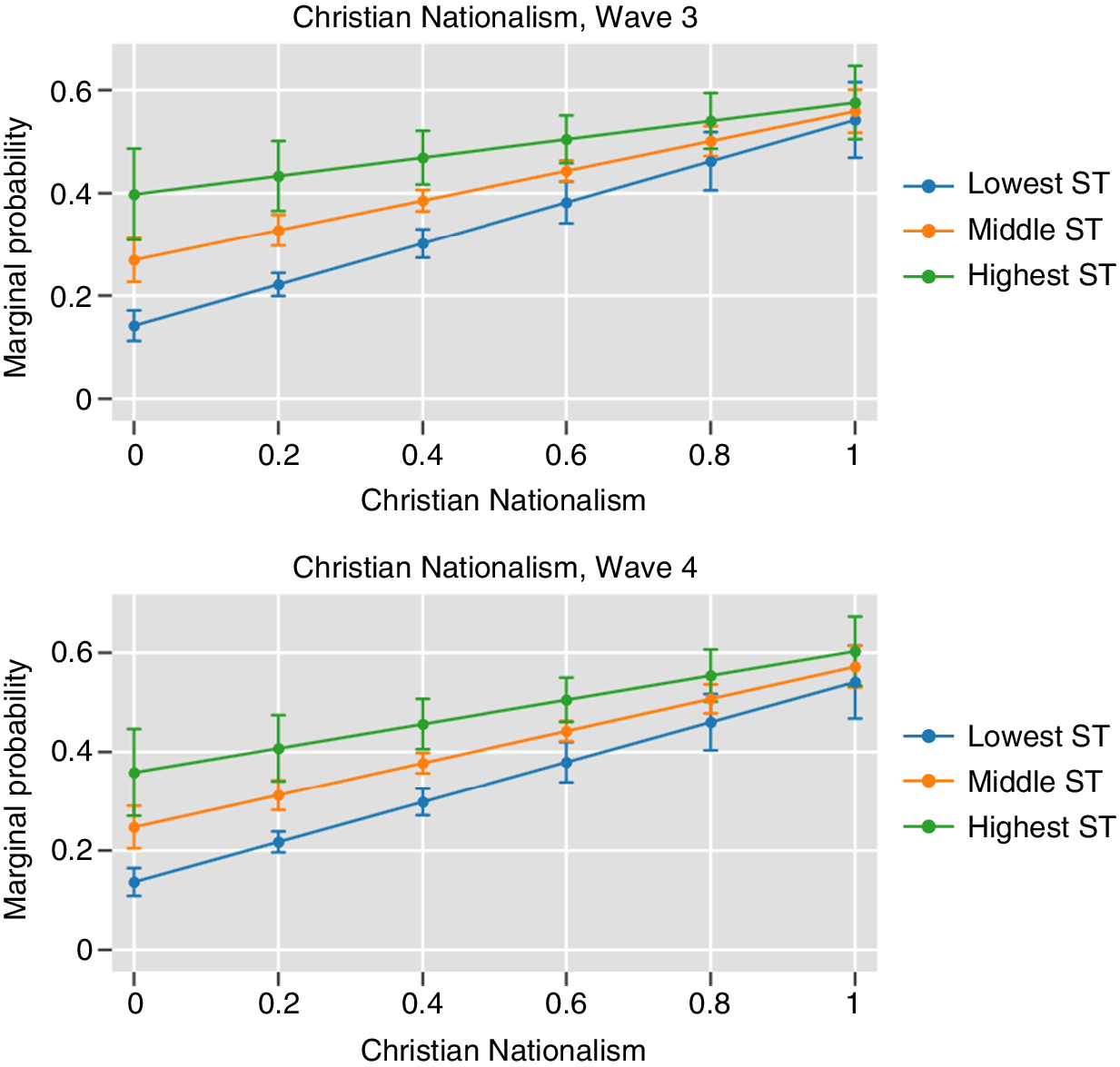

Among the only moderating trends worth noting is that the association between Christian nationalism and group-serving pronatalism is stronger for Americans at the lower scores of the social traditionalism spectrum. As we show in Figure 3, Americans who have the highest and middle scores on the social traditionalism index seem to change little in their support for group-serving pronatalism as Christian nationalism increases, whereas those Americans who score the lowest on social traditionalism show significant differences from others at the lowest end of Christian nationalism. As Christian nationalism increases, however, even those Americans at the lowest levels of social traditionalism become indistinguishable from those in the middle and higher ends in their support for group-serving pronatalism.

Figure 3 Marginal Effects of Social Traditionalism on Support for Group-Serving Pronatalism across Christian Nationalism

NASAS, Waves 1-4 (N = 1,486). Analyses from appendix table A9. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

What undergirds Americans’ support for having children to accomplish instrumental social or political goals, rather than merely personal fulfillment? Building on previous research, we anticipated that Christian nationalism would strongly predict support for “group-serving pronatalism,” and our findings wholly affirm our expectations. Using two measures of Christian nationalism, analyses show that Christian nationalist views are the leading predictor that Americans see having children to reverse the nation’s declining fertility, preserve one’s religious or racial heritage, or secure political influence as good reasons to have them. This is true even after accounting for Americans’ fulfillment-driven pronatalism, social traditionalism, and indicators of religious, ideological, and partisan conservatism.

Using two different measures of Christian nationalism, analyses show Christian nationalist views are the leading predictor that Americans will see having children to reverse the nation’s declining fertility, preserve religious or racial heritage, or secure political influence as good reasons to have children.

Interactions suggest this association is not meaningfully moderated by most measures of conservatism or salient social identities, although Christian nationalism’s association is slightly diminished at higher levels of social traditionalism. This latter finding likely reflects both that Americans who already score the highest on our social traditionalism measure had little room to increase in their support for group-serving pronatalism and that the two variables are strongly correlated (r ≥ .71 for either Christian nationalism measure; see online appendix table A6). Yet, it is worth noting that Christian nationalism does not wash out the influence of social traditionalism in multivariate analyses, suggesting that both contribute something unique to the model. Given the specific measures included in our social traditionalism index, the construct likely accounts for Americans’ support for conventional, patriarchal and heterosexual family relationships, whereas our Christian nationalism measure more likely reflects Americans’ adherence to a mythological narrative of Christian supremacy and a desire to institutionalize that supremacy in the present (Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022).

We also found, however, that Christian nationalism’s influence is not necessarily contingent on characteristics like partisanship, race, or gender as other studies might suggest (Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023; Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022; Perry, McElroy et al. Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022; Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2022). Although it is associated with group-serving pronatalism at the bivariate level, partisanship was not a significant predictor in full models, even before Christian nationalism was included (see online appendix table A7). Thus, it is likely that partisanship did not strongly influence Americans’ views on this outcome in the first place. Race and gender were significant predictors, however, and both were found to significantly moderate Christian nationalism’s association with “nationalist pronatalism” in Perry, McElroy, et al.’s (Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022) analysis. Those authors use a slightly broader Christian nationalism measure, and thus, the relative precision of our two measures may result in more uniform associations across race and gender. Additionally, our outcome measures are also more specific, focusing on explicitly group-serving reasons to have children, rather than on broader support for addressing declining national fertility or encouraging couples to have more children. Given Christian nationalism’s obvious implications for issues of partisanship, race, and gender, future studies should continue to examine how these factors may moderate its influence on similar outcomes.

Acknowledging several data limitations of our analyses can help chart a path for future research. First, the data are cross-sectional, and thus we cannot definitively establish causal direction. Experimental designs that prime Christian nationalist views (e.g., Al-Kire et al. Reference Al-Kire, Pasek, Tsang and Rowatt2021; Walker and Haider-Markel Reference Walker and Haider-Markel2024) would be an ideal next step to discern whether evoking political, cultural, or demographic threat might prime Christian nationalism and then lead to increases in support for group-serving pronatalism. Moreover, Perry, McElroy, et al. (Reference Perry, McElroy, Schnabel and Grubbs2022) used measures of perceptions of discrimination against Whites and Christians and a common measure of patriarchal ideological views, the latter of which was strongly associated with “nationalist pronatalism.” Although our social traditionalism index likely captures much of this latter construct, we acknowledge that we were not able to account for the same variables. Moreover, although our study is only able to focus on hypothetical support for group-serving reasons to have children, future studies could extend these findings with surveys of soon-to-be parents or current parents asking them to indicate the reasons they had children. These accounts would need to be cross-checked because family decisions are often so laden with symbolic meanings that convey status in certain religio-political subcultures that persons may misrepresent their actual reasons (see Perry Reference Perry2017, Reference Perry2024). Yet, even these accounts would reveal more about what such subcultures value. Ethnographic data would also be helpful for understanding how childbearing choices are contextualized in conversations or in public gatherings.

Data limitations notwithstanding, our findings hold implications for understanding rhetoric involving pronatalist policies like those of Victor Orban or Vladimir Putin, claims by Donald Trump that he would support “baby bonuses for a new baby boom,” or J. D. Vance’s proposal that the government cover the cost of childcare, explicitly citing Orban’s policy. These and other proposals come from MAGA Republicans who, like Orban, run on anti-immigration, pro-Christian nationalism campaigns (Vesoulis Reference Vesoulis2023). Our findings suggest their messages will likely find resonance with Americans who are not merely social traditionalists or find children personally fulfilling but who also hold firmly to a belief in America’s conservative Christian foundations and desire to explicitly preserve or restore Christian supremacy in the nation’s identity, values, and even laws.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096524001069.

DATA AVAILABLITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QHDPQK.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.