During the last couple of decades, numerous initiatives undertaken by institutions (private and state libraries and collections, museums, ecclesiastical foundations, connoisseur's societies, etc.) in the possession of medieval manuscripts have been concerned with their digitization and the creation of digital libraries for their online display. These endeavors have generally been driven by practitioners’ interests in reconciling their conflicting obligations to preserve the materials while also providing intensive access to these fragile artifacts (Nichols Reference Nichols2008; Shafir Reference Shafir2013). Nevertheless, they often still prioritize texts over materiality. Moreover, in many such initiatives, standardization of data, tools, and systems has not been a major concern (Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). As a result, the digital surrogates and the environments created for hosting them are designed fast and, in some cases, without the necessary research regarding requirements for users ranging from scholarly to general audiences (Edwards Reference Edwards2013; Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018).

Although the majority of scholarly users tend to be interested in the textual content of these digital collections (Kropf Reference Kropf2017; Shafir Reference Shafir2013), a small number (e.g., codicologists, art historians, book historians, book archaeologists) are interested in their extratextual features (Table 1), which are often considered secondary (Edwards Reference Edwards2013). Unable to access the actual artifacts, mainly because of their geographic dispersion, scholars accessing their digital surrogates remotely have no option but to trust these surrogates in whatever form they have been captured. Yet, scrutiny of the surrogates on digital screens does not always allow users to obtain the information they are looking for. In some cases, this information can be provided by the metadata that accompany surrogates, but again it cannot be verified easily or revised, if necessary (Edwards Reference Edwards2013; Kropf Reference Kropf2017).

TABLE 1. List of Extratextual Features of Manuscripts.

The question of whether and to what degree we can cater to the special needs of individuals interested in the different extratextual features of online manuscripts is an underappreciated matter. It hence forms the focus of this review, where I explore the issue with specific reference to databases comprising digital surrogates of Greek New Testament manuscripts created by different categories of institutions (public, academic, and ecclesiastical) located in Greek-speaking regions (Greece and Cyprus), Europe, and the United States.

SCHOLARLY WORK WITH MANUSCRIPT DIGITAL SURROGATES: NEEDS

For manuscript curators, the goal of designing digital surrogates and associated repositories whose delivery features can respond to the needs of every scholarly group is challenging, limited by technical, resource, and time-related constraints (Edwards Reference Edwards2013; Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). The needs of users working with digital surrogates can be condensed into two fundamental prerequisites: accessing (i.e., being able to see the physical features of the manuscripts) and assessing the features of interest quickly and efficiently whether knowing what to look for or not (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Schema of the needs of users working with digital surrogates of manuscripts.

When it comes to the needs of users interested in the extratextual features of manuscripts, the realizable levels of efficiency regarding accessibility and assessment can vary significantly. Practitioners have already pointed out that the material and structural features of manuscripts are often neglected (Edwards Reference Edwards2013; Kropf Reference Kropf2017). Such neglect relates in part to decisions taken during the digitization process to include—or not—reference to them, mainly because of overlooking the needs of users who may be interested in extratextual features. It is important for some users to be able to study the physicality of the manuscripts and, in particular, to grasp their real sizes and colors (Edwards Reference Edwards2013). For instance, these considerations are crucial when dealing with artifactual production patterns, questions of style, and provenance.

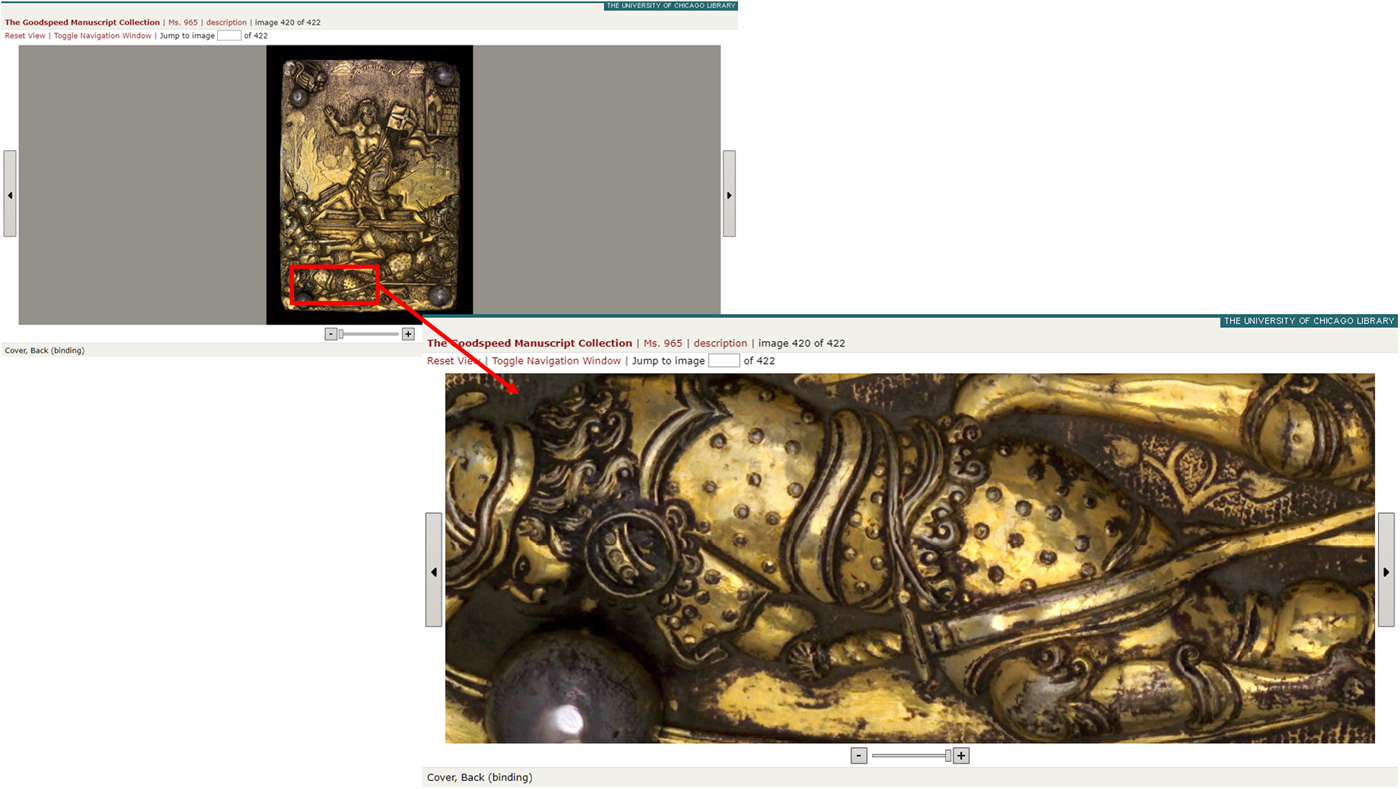

Equally critical are the possibilities provided by the way images and information regarding extratextual features are presented and made available and assessible, through the method of image display and the digital tools that can support scholarly work (Nichols Reference Nichols2008; Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). Image presentation (e.g., through thumbnails, single and/or full-screen imagery, single- or double-page views, simultaneous views of images) can have an impact on the way the physicality of the manuscript is replicated, the efficiency of the end user's workflow, and their ability to forge a first general impression of the entire manuscript before entering into detailed analysis of it. Image display can moreover enhance the rapidity of access to points of interest in the same way that tags, fully labeled navigation bars, or metadata entries with links and/or folio numbers allow (Kropf Reference Kropf2017). Moreover, digital tools can provide unique insights, sometimes impossible to gain even when consulting physical manuscripts. For instance, the ability to assess at high magnification color images of illuminations/decorations, of the structural characteristics of the manuscripts, or of other various physical details guarantees a higher potential performance for the digital surrogate. It also allows the gathering of evidence related to textures, materials, the methods of work of scribes, illuminators, and various craftspeople involved in the manufacture of the manuscripts (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. University of Chicago Library's Goodspeed Manuscript Collection viewer with an image of the repoussé metallic decoration of the back cover. On the right, detail of the cover at high magnification. It is presented using Zoomify software that allows for fast zooming and panning of high-resolution files over the web. The manuscript showcased here is Chicago, University Library, Goodspeed collection, 965 (also known as the Rockefeller-McCormick New Testament; http://goodspeed.lib.uchicago.edu/).

WORKING WITH GREEK NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS ONLINE: ARE THESE SURROGATES ENOUGH?

The actual number of collections that include Greek New Testament manuscripts cannot be easily estimated. After the first large-scale digitization projects undertaken by eminent institutions (e.g., British Library, Bibliothèque Nationale de France), smaller ones followed their example (Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). While these projects have allowed remote access to institutional holdings, the possibilities for detailed scholarly investigation of these holdings vary considerably. The availability of resources (time, cost) is often the reason behind the technical and workflow options that might limit the optimal presentation of digital collections. My interest, though, is in whether priority should be put on digitizing and putting online material that is otherwise difficult or even impossible to look at—or, alternatively, if this priority should go to offering more refined possibilities (Holsinger Reference Holsinger2012) for the exploration of features of the manuscripts, thus focusing investment less on ubiquitous “access” and more on meaningful episodes of engagement. The recent digitization initiatives undertaken by ecclesiastical institutions in Greece and Cyprus provide a case in point in terms of their efforts to make unknown manuscripts accessible for the first time. These cases validate the argument that emphasis should be put, at least in the first instance, on accessibility (Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018; Shafir Reference Shafir2013), given that initiatives from ecclesiastical institutions are extremely scarce despite the number of physical collections available in the Greek-speaking regions. Such institutional efforts demonstrate changes—albeit slow in nature—to the mentality of the decision-makers of the Greek Orthodox church who are increasingly allowing, through new media and the web, glimpses into the church's dogma, heritage, and traditions. Recognition of the impact of digital culture on society has obliged ecclesiastical authorities to revise their once-skeptical position toward digital technologies, appreciating them now as new means for reaching out to younger generations (Halabi Reference Halabi2012:132–146).

The databases of the Leimonos Monastery on the island of Lesvos (Moni Leimonos manuscripts’ database, http://web.pvaigaiou.gov.gr/leimonos/library/index.php) and the Monastery of Saint Neophytos (Enkleistra) in Cyprus (Saint Neophytos manuscripts’ database, https://apsida.cut.ac.cy/items/browse?collection=39) were created recently these links can be accessed from a connection provided by the Greek government services, i.e., University Libraries, Ministry of culture etc. but not by private connections. Neither of them is complete, though, in the sense that they both include just a portion of their holdings. The Leimonos database mentions this fact (“This website presents part of Leimonos' written wealth”), while in the case of the Enkleistra database, bibliographic research is necessary for the user to verify its partial nature (e.g., Constantinides Reference Constantinides1988–1989; Weyl Carr Reference Weyl Carr, Bryer and Georghallides1993). In the first case (Leimonos database), it is not clear what the criteria are for excluding certain manuscripts. In the latter case (Enkleistra database), the illuminated, and thus the most precious manuscripts of the collection (mss. 11 and 12), have been excluded, leading to questions about the criteria used for the selection of the digitized manuscripts (Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018).

Despite their similar interface in PDF format, which can be loaded only in a separate tab (Figure 3)—thereby allowing the user merely to scroll through the manuscript—the range of information provided for each varies significantly. The surrogates in the Leimonos database are accompanied by a very detailed description of the contents (text, notes, inscriptions) indicating their exact position (folio number) and the paleographical and codicological characteristics of the manuscripts but have no mention of their decorations or illuminations (e.g., http://web.pvaigaiou.gov.gr/leimonos/library/view_more_en.php?id=269&status=1&type=manuscript). The Enkleistra database provides images of the written folios only, forbidding assessment of the structural characteristics of the manuscripts. The descriptions, if present, include very basic information limited to date, content, dimensions, and number of folios (e.g., https://apsida.cut.ac.cy/items/show/26090).

FIGURE 3. Interface of the databases of the Enkleistra (top) and Leimonos (bottom) monasteries. On the left we see the description of the manuscript. On the right is a clickable image of the manuscript that loads the digital surrogate in PDF format. The manuscripts showcased here are Paphos, Monastery of Saint Neophytos, 5 (top); and Lesvos, Leimonos Monastery, 295 (bottom).

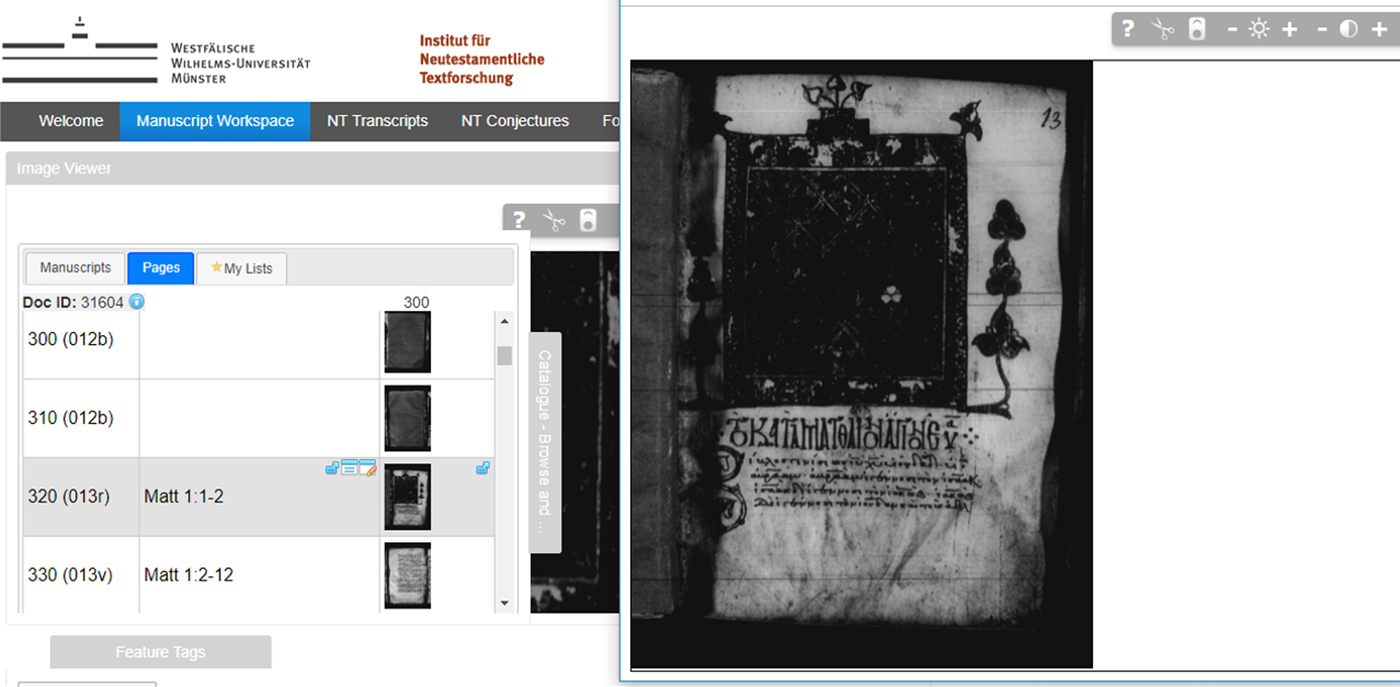

Two projects—the first initiated by a German institution (Institute for New Testament Textual Research, University of Münster) and the second following the initiative of a U.S. New Testament scholar, Daniel B. Wallace (Center for the Research of Early Christian Documents, Dallas Theological Seminary)—have resulted in the creation of two databases, the New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room (NTVMR; http://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/home) and the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM; http://csntm.org/), both designed to support biblical scholarship. NTVMR is an extremely valuable repository since it allows access to the most important corpus of images from biblical manuscripts from around the world. However, accessibility might be restrictive in some cases: to use the database, the administrator of the site needs to be contacted with an explanation for why access is needed. An account is then created for which final approval is necessary. Once access is obtained, the range of tools provided for the detailed textual study of the manuscripts can be also useful and explored by scholars interested in extratextual features. Indicatively, users have the ability to add tags—for example, for making notes or for easier retrieval—and to significantly magnify an image that can also be displayed in an embedded external viewer (while the rest of the manuscript remains displayed in the initial window, in thumbnails, allowing comparisons of features; Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. NTVMR's interface with a color digital image magnified in the embedded external viewer. The manuscript showcased here is Münster, Universität Münster, Bibelmuseum, gr. 10.

However, in some cases the surrogates pose serious restrictions on users interested in extratextual features, offering little to no improvement on—indeed, perhaps even proving retrogressive in relation to—previous methods of digital preservation and access. Many of them derive from grayscale scans of microfilms that often exclude images of the structural elements of the manuscripts. Moreover, beyond the absence of color, their quality is low and the views are distorted, since digitization standards were obviously not followed by photographers and manuscript custodians (e.g., ecclesiastics, nonspecialized staff), probably because of lack of awareness of such standards or simply owing to rushed efforts to digitize large numbers of manuscripts very quickly. As a result, iconographic and stylistic assessment of miniatures and decorations based on these surrogates is almost impossible (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. NTVMR's interface with a grayscale image magnified in the embedded external viewer. This image was derived from a grayscale scan of a microfilm. The manuscript showcased here is Athos, Vatopedi Monastery, 976.

NTVMR's value lies in the fact that the available surrogates constitute the only point of access to manuscripts that are usually preserved in institutions lacking the necessary resources for creating full digital repositories. Many of these institutions are also seemingly reluctant to allow wide access to their collections, excusing their exclusivity by suggesting that digitization initiatives could trigger the looting of their patrimony or uncontrolled reproduction through publications and unconstrained commercial reprint of manuscripts’ images. Greek Orthodox monasteries are especially prone to such exclusivity, although it is worth mentioning that, for the first time, the monasteries of Mount Athos have agreed to digitize—adhering to certain technical standards—an important number of their manuscripts and archives for use on the web. It is therefore expected that the Athoniki Psifiaki Kivotos (Athonite Digital Arc; http://www.athoskivotos.eu/index.html), which will go online in 2019, will make a significant impact on the field.

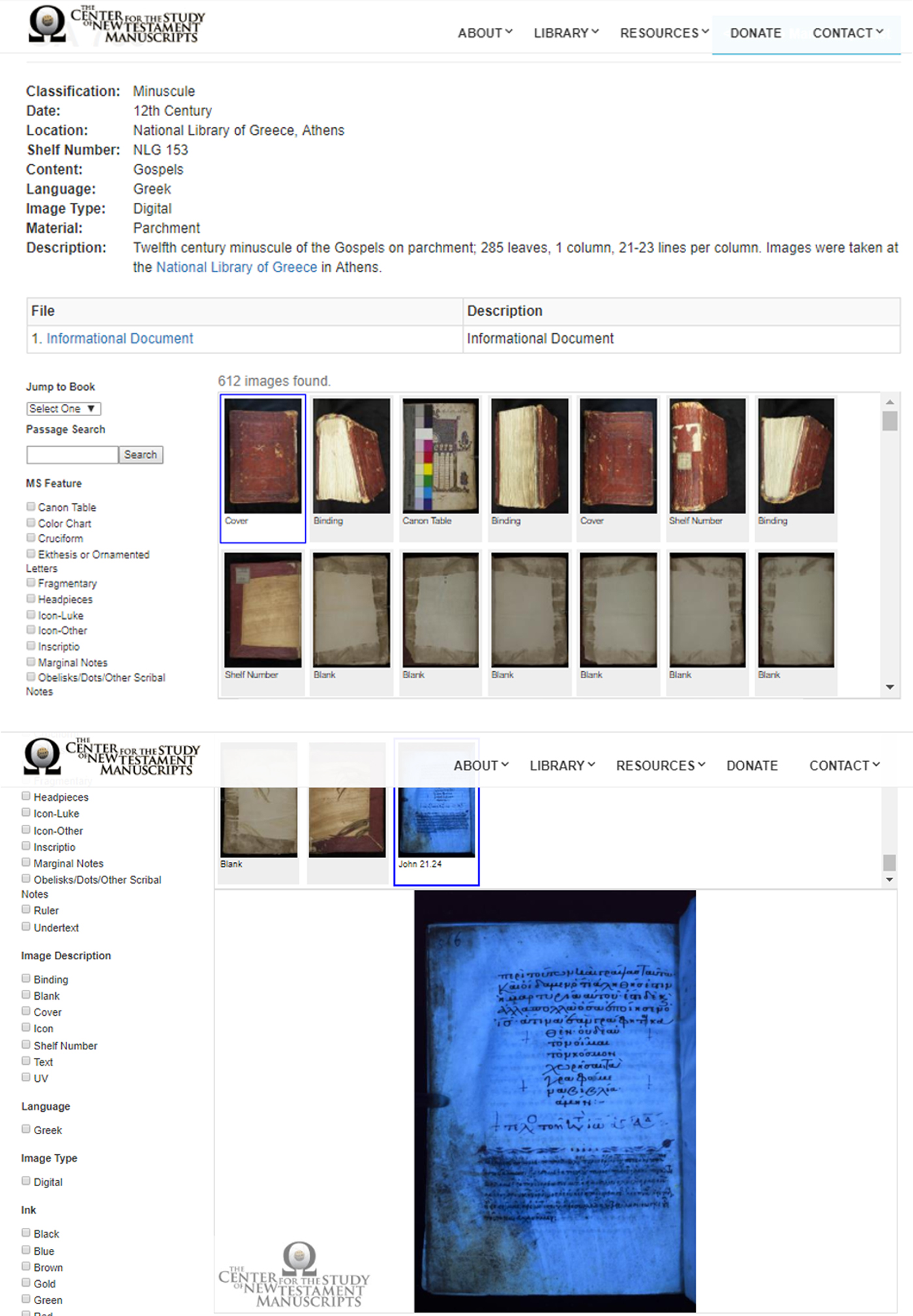

In contrast, the mission of CSNTM—to produce high-quality images of New Testament manuscripts by bringing a high level of professional expertise to the technical task of photography—has resulted in the creation of a substantial, freely accessible repository. The quality of the digital surrogates suggests a move away from bulk digitization toward a concern for surrogate performance, permitting the exploration and accumulation of knowledge and understanding about the manuscripts, as recently proposed by Prescott and Hughes (Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). The performance of the CSNTM surrogates is actually high since they allow the efficient accessing and assessing of physical and structural features of the manuscripts via provision of a sequence of images of the cover, the binding, and the edges, plus a photo of a written folio with a ruler and a color chart (Figure 6, top). More recent acquisitions demonstrate that it is possible to continue contributing to the exploration and investigation of the manuscripts (Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). Thus, photographs captured with UV imaging showcase detected palimpsests (i.e., text written over parchment folios that were effaced and reused), and in some cases even allow the deciphering of erased/damaged text (Figure 6, bottom).

FIGURE 6. CSNTM's interface with a sequence of images (top). UV image of a folio with damaged text (bottom). The manuscript showcased here is Athens, National Library of Greece, 153.

Yet the way these excellent surrogates are presented still restricts their great potential. The ability to magnify significantly the high-resolution images is indisputably an asset, even though this is the only tool in support of detailed scholarly analysis of extratextual features. The viewer, however, is restrictive, as it does not offer the possibility for simultaneous views of full materials but only of thumbnail shots of the rest of the folios. Neither is there a possibility to have a double folio (verso-recto opening) view that could permit the user to consider how the physicality of manuscripts is/was affecting the experience of readers. For instance, in some manuscripts, images on opposite pages (verso-recto) are often placed such that their iconography mirrors or converses with each other. In medieval iconography, we encounter juxtaposed (in the same image or on the opposite folio) iconographic motifs that function as examples and counterexamples of faith, humility, etc. (Toumpouri Reference Toumpouri and Tsamakda2017). Hence, in the latter case, if the reader is not offered a view of the manuscript opening (double folio), then the didactic purpose of the creator/planner of the manuscript can be easily missed. A single folio view is therefore a sort of decontextualization of the object, its texts, and its images.

More positively, and unlike NTVMR, CSNTM provides a great deal of information that meets the needs of those interested in extratextual features via a document (in PDF format) that accompanies the surrogates (see, e.g., Athens, National Library of Greece, 153; http://images.csntm.org/Manuscripts/GA_760/GA_760_prepdoc.pdf). These detailed codicological descriptions enhance the already high efficiency of CSNTM's surrogates. They furthermore compensate for the weaknesses of the viewer by allowing users to navigate directly to features of interest through a detailed list of the location of the manuscript's decorative elements and illuminations (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Section of the description (PDF document) that accompanies the CSNTM digital surrogate of ms. Athens, National Library of Greece, 153. Here we see the detailed list of the decorative elements and miniatures of the manuscript.

WHAT'S NEXT?

The digitization efforts undertaken by different categories of institutions, including ecclesiastical ones that were previously reluctant to invest in such work, indicate that barriers toward the democratization of heritage are slowly being dismantled. We can perhaps accept that manuscripts were originally created for transmitting knowledge and that their texts will always be of importance to scholars. Yet manuscripts are more than mere text carriers, and understanding them thus necessitates moving beyond what is written, to consider their materiality, since they are complex pieces of craftwork (Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018). As technology and scholarly needs are constantly evolving, so the responsibility of institutions holding manuscripts is to invest in long-term collaborations with specialists/users who know what they want and have already been trained in, exposed to, or are appreciative of the importance of material literacy (Edwards, Reference Edwards2013; Kropf Reference Kropf2017). In the meantime, manuscripts remain unopened on the shelves of libraries with the excuse that their images exist online, but current digital surrogates do not yet instill the appreciation and necessary knowledge that can inform future digitization and database initiatives. This predicament negatively impacts on critical and reflective discussions about the digitization and online display of manuscripts, further postponing the development and creation of tools and initiatives that could significantly advance the field of manuscript studies (Kropf Reference Kropf2017; Nichols Reference Nichols2008; Prescott and Hughes Reference Prescott and Hughes2018).

Acknowledgments

I would like to gratefully acknowledge the reviewers and editors for their valuable comments and suggestions. Sara Perry is particularly thanked for the support and patience she generously offered throughout the preparation of this article.