In 2006, the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) issued a Statement of Professional Standards regarding the role of the pharmacist in responding to crises, including pandemics and manmade or natural disasters. 1 This document notes the many ways that pharmacy personnel can work to mitigate harm following an emergency event. It also specifies additional actions that should be taken to enable members of the pharmacy profession to work to their full potential in alleviating hardship during a crisis. Since the above statement was issued, members of the Military and Emergency Pharmacy Section of the FIP have conducted additional work in this domain, and a comprehensive document was recently published to provide guidance to pharmacists working in national associations, governments, industry, hospitals, and community pharmacies in responding to natural disasters. 2 Similar statements and guidance documents have also been made by other pharmacy organizations and regulatory bodies in North America. 3 - 5

Unfortunately, despite the directives issued by practice leaders and regulatory bodies, the available literature suggests that recommended infrastructure and operating procedures are not being adequately implemented in pharmacy workplaces. In 2016, Ford et alReference Ford, Trent and Wickizer 6 assessed the degree to which US state boards of pharmacy had implemented the Rules for Public Health Emergencies issued by the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. These rules—which address many issues of practical importance, such as emergency refills, temporary relocation of pharmacies, and employment of out-of-state pharmacy personnel in support of disaster relief—were established following the challenging 2005 hurricane season. 4 However, nearly one decade later, the median number of rules adopted among all boards was 1, and only one board had adopted all 8 rules.Reference Ford, Trent and Wickizer 6 Pharmacists may therefore lack the frameworks and legal authority required to practice in a responsive manner following disasters. Lack of uptake of established guidance was also evident in a 2013 survey of hospital pharmacies in New Jersey, with only 10 of 18 respondents having a pharmacy-specific component to their institutional emergency plan.Reference Awad and Cocchio 7 Responses to other questions on this survey further suggest that such planning may not have been based on recommended guidelines, and quantities of medications may therefore not have been sufficient for a mass casualty event.Reference Awad and Cocchio 7

More discouragingly, earlier reports evaluating diverse groups of health care personnel have found many behaviors and competencies related to emergency response to be suboptimal among pharmacists.Reference Crane, McCluskey and Johnson 8 - Reference Seib, Gleason and Richards 10 Crane and colleaguesReference Crane, McCluskey and Johnson 8 evaluated Florida health care providers’ preparedness to respond to a bioterrorism attack, using measures of their self-reported ability to perform various clinical and administrative activities. For the pharmacist subgroup, major deficits were identified in 5 of the 8 clinical competencies evaluated. When combined with their low willingness to respond, pharmacists overall appeared to be less prepared than either physicians or nurses for a potential bioterrorism attack.Reference Crane, McCluskey and Johnson 8 In a separate report, Durante and colleaguesReference Durante, Melchreit and Sullivan 9 assessed training needs in real time among personnel participating in a simulation involving mass distribution of antibiotics from the Strategic National Stockpile. Among the 7 dispensing facilities established for this exercise, a total of 266 participants provided valid information regarding their training needs, 11% of whom were licensed pharmacists.Reference Durante, Melchreit and Sullivan 9 Compared with other individuals with a professional certificate (a diverse grouping which included sanitarian workers, emergency medical technicians, social workers, and physician assistants, among others), pharmacists were significantly more likely to indicate that they required additional training in 5 or more competency areas.Reference Durante, Melchreit and Sullivan 9 Finally, in a more recent review of H1N1 vaccine providers published in 2013, notable differences were again seen between pharmacists and other health professionals, with lower rates of staff vaccination coverage for influenza, greater reliance on sources of information other than local health units (including federal sources, news media, internal thought leaders, or corporate headquarters), and lower rates of participation in emergency training.Reference Seib, Gleason and Richards 10

None of the above findings should be surprising. In the studies by Crane et al and Durante et al, the authors attempted to perform comprehensive assessments of the participants’ ability to function as part of a response team during an emergency. As a result, profession-specific task performance (eg, the ability to accurately dispense medications) did not factor heavily into the final scores. Pharmacists’ excellent dispensing skills and strong therapeutic knowledge related to medications would not have been sufficient to ensure that they could confidently perform the full range of activities deemed essential during an emergency, such as communicating risks to patients, identifying and initiating care for exposed individuals, and addressing psychological impacts of disasters among victims and colleagues.Reference Crane, McCluskey and Johnson 8 , Reference Durante, Melchreit and Sullivan 9 Furthermore, while pharmacists individually are very capable of safely dispensing medications to individual patients, they generally do so as part of a broader system that includes a large number of support personnel and in practice settings that have significant technological aids in place. Competency to dispense in these types of resource-rich environments does not necessarily mean that the same personnel will be equally proficient in “mass dispensing” or other forms of medication supply that occur during emergencies, where existing supply chains are disrupted, information is limited, and key infrastructure may be compromised. Community pharmacists who work in retail settings are also understandably more likely to refer to alternate chains of command for guidance in an emergency situation,Reference Seib, Gleason and Richards 10 given that local public health agencies exert little or no influence on their day-to-day operations. This group of personnel would therefore be particularly challenged to identify appropriate sources of information for onward transmission to patients and members of the public in the event of an emergency.Reference Crane, McCluskey and Johnson 8 - Reference Seib, Gleason and Richards 10 All of these issues have been raised repeatedly in “lessons learned” and other reports of pharmacists who have encountered emergency situations.Reference Hogue, Hogue and Lander 11 - Reference Austin, Martin and Paul 14

It is clear from the literature that individuals and communities that have prepared in advance for natural disasters and foreseeable emergencies are better equipped to respond in times of crisis and experience better health and functional outcomes in the aftermath.Reference Morton and Lurie 15 - Reference Masten and Obradovic 17 During emergency situations, it is imperative that all team members, regardless of their training or background, have a clear understanding of their collective roles and responsibilities, so they can work together to efficiently address all health threats that arise. For pharmacists and their supporting personnel, the delivery of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies is generally accorded highest priority following an emergency event, along with interventions to ensure appropriate use of products that are scarce in supply. However, given the findings in the studies cited above, it appears that pharmacists, and by extension other pharmacy personnel, stand to benefit more substantially from training that allows them to articulate their roles and responsibilities more clearly as they relate to general emergency management.

Many documents already exist that highlight pharmacy roles and contributions in emergency response. 1 - 5 , Reference Pincock, Montello and Tarosky 18 - Reference Woodard, Bray and Williams 20 Most of these aim to provide an exhaustive list of activities, and many of these activities will necessarily relate to medical supply functions. But other activities that are generally accepted as essential to ensure a robust emergency response—such as making arrangements for alternate care of dependents and maintaining up-to-date vaccinations among responders—may go unstated, or will be displayed less prominently, and are thus likely to be downplayed or assigned lower priority as part of pharmacists’ overall emergency preparedness efforts. Available guidance documents also tend to be directed specifically at pharmacists 2 , Reference Pincock, Montello and Tarosky 18 , Reference Bell and Daniel 19 or other narrowly defined audiences (eg, foreign health teams 21 ), and thus do not promote involvement of the full range of pharmacy personnel. They are also of limited use in facilitating collaboration between pharmacy practitioners from different geographic areas, who may be required to respond jointly to a large-scale event.

To ensure an effective emergency response can be mounted, individual members of pharmacy response teams must first work together to articulate their roles and responsibilities, and thereafter, high-priority duties must be assigned to appropriately qualified personnel. Designated personnel must in turn perform all necessary actions, both for individual and family preparedness as well as for personal professional development, so that assigned tasks can be executed within defined timeframes before, during, or after the emergency event itself. The work reported here represents our efforts to develop a framework that will be versatile enough to be used by a wide range of pharmacy practitioners, to support them in developing a general emergency response plan that is relevant to their areas of practice. The cataloging of medical supply activities, which will vary and evolve over time depending on the nature of the affected health care systems and the circumstances of specific emergency events, is being undertaken as a separate project.

METHODS

Work to develop this framework was conducted in 3 stages. In the first stage, a literature review was conducted to identify core capabilities in general emergency response for pharmacy personnel. During the second stage, a categorization scheme for pharmacy personnel was developed. In the final stage, identified activities were matched to the different categories of pharmacy personnel to develop specific role profiles related to general emergency preparedness and response.

Phase 1: Identification of Core Capabilities

Given the limited amount of time available for analysis, we elected to conduct a focused (rather than comprehensive) literature search using PubMed and gray literature. PubMed searches were completed by using a combination of terms including “pharmacy,” “pharmacy support team,” or “pharmacy support workforce” and “emergency response,” “disaster” (including both “natural” and “manmade”), or “pandemic.” Relevant documents from the gray literature were identified by reviewing websites of relevant organizations active in providing direction and guidance to pharmacists in the domain of emergency response, including the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the World Health Organization, and FIP.

A total of 27 publications were selected for data extraction (Appendix 1 in the online data supplement). These articles were selected on the basis of the language of publication (English only), the level of detail provided in the reports (ie, suitable for extraction into our framework document), and representativeness of a diverse range of pharmacists’ emergency response activities. Reports that predominantly described activities done to facilitate delivery, management, and resupply of medications or health supplies during emergencies were excluded from review.

Activities reported to have been done by pharmacists in anticipation of or following an emergency were then extracted from these articles and collated in a single spreadsheet. Where necessary, activities were either paraphrased or reworded to convey directed action (eg, “Adhere to professional guidelines, including requirements for licensure and scope of practice” instead of “All staff must be registered to practice in their home country and have license for the work they are assigned to by the agency”Reference Morton and Lurie 15 ). Some activities extracted from these articles were later deemed to be more closely related to medical supply functions (eg, identifying medications for stockpiles) and were set aside for subsequent review. The remaining activities, which pertained more generally to emergency response and preparedness, were then regrouped under common themes and duplicates were removed. Further consolidation of similarly themed activities was also undertaken to allow key activities to be supplemented with specific examples (eg, ensure conformity with existing legislation, including those pertaining to (1) narcotics and controlled substances, (2) hazardous materials, and (3) emergency-specific supplies such as stockpiles).

To ensure broad applicability, the consolidated list of activities was then revised once again to better align with other guidance on public health and emergency preparedness. 22 - Reference Subbarao, Lyznicki and Hsu 24 Framework materials were also adapted to correspond to 3 time periods, which were loosely defined in relation to onset of the emergency event and clearly situated along a continuum: (1) planning and preparation before an event occurs; (2) early/acute response during a declared emergency; and (3) recovery after the emergency.

Phase 2: Development of a Classification Scheme for Pharmacy Personnel

Eleven articles were drawn from the gray literature (Appendix 2 in the online data supplement) and these were used to inform development of the classification scheme for pharmacy personnel. The majority of these documents originated in Canada, where work to formally regulate pharmacy technicians has been underway in multiple jurisdictions for a number of years, although a few key articles were also international in scope. Distinct classification levels were defined following discussion among the authors, one of whom (SG) has been involved in reviewing lessons learned from multiple disaster response exercises throughout his military career and who has worked extensively with pharmacy professionals from many other countries.

Phase 3: Defining Roles and Responsibilities (Role-Mapping)

During this phase, identified activities were mapped against the newly defined categories of pharmacy personnel. Using the core capabilities and key activities defined in the first phase, and considering specific activities that occur during each of the 3 time periods, a series of role profiles were developed (1 for each of the 4 defined categories). These role profiles illustrated the range of activities that different pharmacy personnel could be expected to undertake. The 4 profiles were then consolidated into a checklist format to enable individual pharmacy practitioners to assess their existing competencies and self-identify areas for future professional development.

RESULTS

Core Capabilities

A total of 505 different work activities were extracted from the 26 identified articles. Of these, 208 (41.2%) were associated with medical supply functions. The remaining 297 activities were then regrouped under 5 broad thematic areas of capability: professional practice, population health planning, direct patient care, legislation, and communications. Further consolidation of these activities allowed for 12 key activity areas to be identified against these 5 areas of core capability. Core capabilities are listed and associated key activities briefly defined in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Core Capabilities and Key Activity Areas for Pharmacy Personnel Working in Emergency Preparedness and Response.

Classification Scheme for Pharmacy Personnel

Four categories of pharmacy personnel were defined (Table 1). Distinctions between the different types of personnel were made by considering the following 5 characteristics:

-

1) Level of pharmacy-related education completed;

-

2) Amount of work experience or practical training in a pharmacy setting;

-

3) Other non-pharmacy specific skill sets that are present;

-

4) Day-to-day tasks performed within a pharmacy (dispensary); and

-

5) Level of independence that can be afforded to the individual when performing pharmacy-related activities.

Table 1 Categories of Pharmacy Personnel Involved in Emergency Response

In addition to 2 categories of pharmacist, the described categorization scheme also includes 2 categories that attempt to capture the variation that exists among nonpharmacist support personnel. We use the term “dispensary assistant” here to refer collectively to individuals who are not registered with a regulatory body but who are legally permitted to perform activities within a pharmacy (ie, under the direction or supervision of a licensed professional). This allowed the full range of pharmacy staff to be assessed and their suitability for specific emergency roles to be determined. Additional detail regarding on-the-job training and practical experience was included, recognizing that formal training programs and regulatory frameworks may not always be in place where disasters occur and that there can be important variations in licensing and practice standards for the same personnel across different jurisdictions.

Role-Mapping

Role profiles were created by regrouping defined activities against capability areas and against different categories of practitioners, across the 3 time periods. This structure accounts for the fact that individual pharmacy practitioners may adopt different roles at different times. For example, clinical pharmacists with specialties in infectious disease, critical care, or radiopharmaceuticals could be expected to act in a Category 4 role when developing an organization’s emergency plan for disasters in their area of expertise. However, if an emergency in an unrelated therapeutic area occurs, such pharmacists could be reassigned to perform Category 3 activities (eg, provide medications according to established treatment protocols).

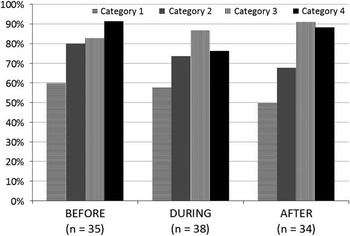

The role profiles currently identify 107 separate activities (Appendix 3 in the online data supplement). The number of activities was relatively balanced across all 3 time periods, with 35 activities (32.7%) assigned to the time period “before,” 38 (35.5%) to “during,” and 34 (31.8%) occurring “after” the event. However, burden of work—as indicated by discrete numbers of activities performed—fluctuated over time, depending on the category of personnel involved (Figure 2). Personnel in Categories 1 and 2, who had primary responsibility for clerical, administrative, and low-level technical duties, performed a progressively smaller number of activities over the course of the emergency response. Category 3 personnel performed more activities over time, whereas Category 4 personnel exercised a more narrowly focused role during the emergency itself.

Figure 2 Proportion of Activities Performed by Different Categories of Pharmacy Personnel Over the Course of an Emergency Response.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this work represents the first attempt to generate a broad framework for pharmacy-related activities in general emergency management. Given the variability noted in the definitions of competencies in this domain,Reference Hsu, Thomas and Bass 25 , Reference Daily, Padjen and Birnbaum 26 we expect that further refinement of our framework will be required. In the meantime, pharmacy practitioners who have reviewed our framework should be better prepared to review, interpret, and act upon health advisories and other guidance relevant to emergency preparedness. By undertaking many of the activities we have identified as necessary in the time period before an emergency occurs, pharmacy team members are likely to come to a better understanding of the hazards that exist within their practice settings, their communities, and the communities of their patients. In this way, pharmacists may be better equipped to interact effectively with public health and disaster medicine professionals, as well as legislators and other “system players,” to advocate for and develop appropriate risk mitigation strategies. A number of recent emergency-related public health challenges have seen pharmacists exercise key roles that differ substantially from their traditionally defined duties,Reference Seib, Gleason and Richards 10 , Reference Gaudette, Schnitzer and George 12 , Reference Tsuyuki 27 and local public health departments will undoubtedly continue to draw upon these new skills sets as they strengthen their partnerships with pharmacies going forward.Reference Rubin, Schulman and Roszak 28 It will therefore be especially important that pharmacy personnel are well-informed and well-prepared—and not just well-intentioned—to advance discussions on emergency preparedness in meaningful ways.

Identification of activity areas is also expected to assist in developing pertinent training for pharmacy personnel across the entire span of their careers. Prior training has been noted to increase the likelihood that individual health care workers will be willing and able to respond adequately in the event of a disaster.Reference Ogedegbe, Nyirenda and DelMoro 29 - Reference Devnani 31 Repeated training may also serve to reinforce and further encourage preparedness, thus enhancing the capacity for an effective response. Although highly structured, simulation-based training that involves many system players may be highly valued, smaller-scale learning activities involving tabletop simulationsReference Pate, Bratberg and Robertson 32 and exercises targeting low-intensity, high-frequency eventsReference Hendrickson 33 are also likely to prove beneficial. Our work could also conceivably be adapted by community pharmacists, who do not operate as part of a broader organizational plan like their counterparts working in hospitals,Reference Awad and Cocchio 7 to initiate a limited form of training at the level of their individual pharmacy (eg, to simulate a power outage affecting their neighborhood for several hours).

Limitations

This framework represents an intensive amount of work done over a limited period of time. As such, it is possible that some relevant activities were overlooked. However, it is unlikely that any areas of major importance were omitted, given the wide variety of articles reviewed and the repetitiveness of common themes identified therein. Although only 3 authors were involved in this work, each one has had practical experience either in preparing for or working in various emergency scenarios over the past 2 decades in military and civilian health care settings and in industrial workplaces. This experience ensures that a suitably broad range of considerations were made during the identification and collation of activities.

As mentioned previously, the current review did not address activities related to the provision of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, since this subset of activities is being actively addressed in a separate project. This work thus clearly did not capture the full range of expected duties for pharmacists in an emergency situation, but instead highlighted key principles of primary importance that have been relatively neglected in the literature to date.

Future Work

Additional effort should be directed at validating the utility of our proposed framework among different types of pharmacy personnel who may become involved in emergency preparedness or response. Since efforts were made to ensure that the framework would be broadly applicable, we encourage its review by pharmacy practitioners working across the full spectrum of practice settings, including those affiliated with health care institutions (hospitals), community pharmacies, and outpatient health care clinics. Given prior variations observed in pharmacy practice in different countries,Reference Eades, Ferguson and O’Carroll 34 review of this framework should be similarly international in scope.

It may be especially valuable to verify the value and relevance of this framework among individuals who possess pharmacy-related qualifications but do not (or are not legally permitted to) provide direct patient care. This includes researchers and academics; drug information pharmacists; individuals employed by drug plans, pharmacy corporations, wholesalers, or pharmaceutical manufacturers; and staff of pharmacy regulatory bodies. Hogue and colleaguesReference Hogue, Hogue and Lander 11 previously reported their success in enlisting practicing pharmacists with academic appointments at a nearby school of pharmacy to provide care for persons displaced by Hurricane Katrina, an effort that could otherwise have overwhelmed existing pharmacy resources in the host community. Other pharmacy-related personnel could similarly serve as a source of surge capacity during the early response following an event, by undertaking activities that support patient care (eg, adapting drug information materials to convey key emergency-specific information, preparing professional communications in different languages, relaying information regarding pharmacy operations in an affected area to response coordinators). While ongoing provision of care will be of prime importance to those affected by an emergency, our framework has identified 4 other areas of equal value for pharmacists who are proactively preparing to respond to such emergencies. Nonpracticing pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists working in nontraditional settings could provide valuable assistance during the planning and preparation stages of emergency management to establish legislationReference Ford, Trent and Wickizer 6 and other practice elements required by pharmacists responding to an emergency.Reference Bhavsar, Kim and Yu 35

Further work is also underway to investigate learning opportunities for pharmacy personnel who wish to pursue additional training in this field. While numerous public health programs are available worldwide to provide in-depth training in emergency preparedness and response,Reference Algaali, Djalali and Della Corte 36 , Reference Ingrassia, Foletti and Djalali 37 many of these are structured for full-time study and thus would not be feasible for most practicing pharmacists to complete. Such programs would also not address the needs of pharmacy practitioners who lack a university degree or who have limited post-secondary education. Development of a more practical training program that addresses core concepts of emergency preparedness, while allowing for further study and specialization based on individual needs in specific contexts, is likely to be both desirable and highly relevant for pharmacy practitioners practicing in multiple settings around the world.

CONCLUSIONS

A framework has been developed that outlines key activities that different categories of pharmacy personnel can perform to prepare for, respond to, and recover from an emergency event. This framework builds on and addresses gaps in the existing literature and should therefore assist in ensuring a coordinated response among all members of a pharmacy team. Additional work is required to validate the utility of this framework and to identify suitable training opportunities for pharmacy practitioners in this domain.

Acknowledgments

Dr Alkhalili’s portion of this work was completed to fulfill academic requirements for the Doctor of Pharmacy Program at the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of Toronto.

Commander Grenier is currently the President of the Military and Emergency Pharmacy section of the International Pharmacy Federation. The authors disclose no financial relationships of relevance.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https:/doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2016.172