1. Defining step therapy

Step therapy is a managed-care approach to reimbursement of prescribed treatment that is designed to control costs and is the most commonly used coverage restriction for specialty drugs (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Kim, Pope, Graff, Wilkinson and Neumann2018a). In a step-therapy protocol, a person must have tried and found ineffective (failed) one or more therapeutic agent(s) that the insurance company considers first-step before they will be reimbursed for a medication considered to be a second or higher step. Within a step-therapy protocol, the decision about what medication will be reimbursed, and therefore accessible, to a person is not necessarily determined by their medical provider – or evidence-based best-practice clinical guidelines, but rather by the insurance policy algorithm (Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Foromera, Feuerstein, Falchuk and Feuerstein2017).

A review of 50 insurance policies regarding reimbursement of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatments showed that 98% of policies were inconsistent with the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) evidence-based guidelines for ulcerative colitis, and 90% did not follow the AGA guidelines for Crohn's disease. Failing two or more treatments before an evidence-based first-line agent would be reimbursed was required by 34% and 28% of policies, respectively, for these two forms of IBD. Typically, the step-therapy protocols required failed corticosteroid treatment before biologics would be reimbursed, despite evidence and guidelines supporting biologics as first-line treatments and recommending avoidance of long-term corticosteroid therapies (Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Foromera, Feuerstein, Falchuk and Feuerstein2017).

In practice, in states without laws regulating step-therapy practices, or for patients not protected under those laws, this means that health care providers and patients cannot simply partner to choose the best treatment option, but instead must try alternative options mandated by the insurance company or pharmacy benefit management (PBM) company. In the 29 states that require exemptions be offered, patients and physicians must either try the drug the insurance company's or PBM's algorithm allows or complete paperwork justifying their treatment choice. This adds to the already onerous prior-authorization process imposing a burden on the health care provider, the practice and the patient that was estimated by the American Medical Association to cost 14.6 hours per week for every physician in the United States (American Medical Association, 2017).

Not only may patients be required to fail multiple treatments before being able to access the treatment their health care provider identifies as the best option for them as an individual, if they move or change jobs or insurance policies, they may have to fail the same treatment twice (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Kim, Pope, Graff, Wilkinson and Neumann2018a, Reference Chambers, Pope, Bungay, Cohen, Ciarametaro, Dubois and Neumann2018b; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Dhruva and Ros2018).

2. Step therapy and cost effectiveness

As noted, step therapy was designed as a cost savings measure to prevent overuse of expensive treatments in favor of more cost-effective options. The above example of IBD treatments suggest this may be short-sighted, saving immediate costs only to incur complications with potentially increased long-term costs of less effective medications. There is other evidence from multiple areas of medicine that step-therapy policies shift, rather than reduce, costs. A study on the use of step-therapy protocols for antihypertensive medications showed there was an initial decrease in the amount spent on medication that was offset by an approximate increase of $400/year in costs paid directly by patients (Mark et al., Reference Mark, Gibson and McGuigan2009). A study comparing spending on atypical antipsychotics in Georgia and Mississippi Medicaid programs showed that the step-therapy protocol saved Georgia $19.62 per member per month but increased outpatient service costs by $31.59 per member per month, for a net increase of $11.97 per member per month (Farley et al., Reference Farley, Cline, Schommer, Hadsall and Nyman2008). A later narrative literature review found that three of four studies on the economic effects of step therapy for atypical antipsychotics showed overall cost increases, and only one showed modest savings (Rajogopalan et al., Reference Rajagopalan, Hassan, Boswell, Sarnes, Meyer and Grossman2016). In the treatment of neuropathic pain conditions in people aged 65–89, those affected by step-therapy protocols had decreased medical costs and increased disease-related pharmacy costs. Neither total pharmacy costs nor total health care costs, however, differed between the two groups (Suehs et al., Reference Suehs, Louder, Udall, Cappelleri, Joshi and Patel2014).

Some analysis suggests step therapy may also increase costs for insurers. The health care consulting firm Avalere published an analysis modeling patient cost sharing, out-of-pocket expenses and payer liability. They found implementing fail-first protocols could increase total costs paid by the insurer by 37% for individuals who failed the first-step alternative to current best-practice care (Avalere Health, 2020).

The economics of U.S. health care is complex, with multiple players and payors; data regarding which, if any, benefit financially from step-therapy as it is currently implemented are limited. What is clear, however, is that cost-efficacy is not achieved simply by using the lowest-priced drug available, especially if neither overall cost savings nor evidence-based best medical practices are achieved.

3. How fail-first step therapy can harm

Not only are step-therapy protocols failing to provide cost-effective treatments and preventing use of evidence-based best practices, these policies also harm individuals, diminishing adherence to treatment, decreasing quality of life, and risking further disease progression and physical harm (American Medical Association, 2017; Burns, Reference Burns2017; Burns, Reference Burns2018; Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Pope, Bungay, Cohen, Ciarametaro, Dubois and Neumann2018b; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Dhruva and Ros2018; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Kesselheim, Lu, Ross, Tessema and Avorn2019; Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2018; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Jones, Compton, Losby, Murimi, Baldwin, Ballreich, Thomas, Bicket, Porter, Tierce and Alexander2018; Park et al., Reference Park, Raza, George, Agrawal and Ko2017; Wirrell et al., Reference Wirrell, Vanderwiel, Nickels, Vanderwiel and Nickels2018, Doshi et al., Reference Doshi, Puckett, Parmacek and Rader2018).

Step therapy is used millions of times per year with no harm to patients, but there are instances where these practices hurt patients by

• creating additional barriers that can lead people to forgo needed medications (American Medical Association, 2017; Park et al., Reference Park, Raza, George, Agrawal and Ko2017; Potter et al., Reference Potter, Maldonado, Lentine, Schnitzler, Zhang, Hess, Garrity, Kasiske and Axelrod2018; Wirrell et al., Reference Wirrell, Vanderwiel, Nickels, Vanderwiel and Nickels2018)

• causing patients' medical conditions to deteriorate, thereby increasing the need for more medical intervention and thus raising the cost of health care while decreasing health of the patient (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2018; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Dhruva and Ros2018)

• increasing frustration and incidence of depression (Park et al., Reference Park, Raza, George, Agrawal and Ko2017; Potter et al., Reference Potter, Maldonado, Lentine, Schnitzler, Zhang, Hess, Garrity, Kasiske and Axelrod2018)

• increasing the risk of nonadherence and self-medication (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Dhruva and Ros2018)

In our work with the arthritis, migraine, cardiovascular and osteoporosis communities and advocacy groups, we have taken the position that we prefer patients to succeed first by taking the medication prescribed by their health care professional.

This is not to say that physicians and patients shouldn't include cost as part of the risk–benefit analysis when they choose among treatment options. However, what is cost-effective for the overall population, or a particular player in the health care system, may not be the most cost-effective or even an effective choice for a given individual (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Pope, Bungay, Cohen, Ciarametaro, Dubois and Neumann2018b). Many health care professionals, either because they believe a step-therapy protocol is correct or don't have the time or inclination to argue against it, follow step-therapy procedures (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Kesselheim, Lu, Ross, Tessema and Avorn2019). In practice, this means therapy choice may be driven not as a medical decision in the physician–patient partnership, but rather as a decision made by a company financially incentivized to use the drug that costs that company the least amount.

Determining cost-effectiveness of a drug is also complicated by the fact that although a relative efficacy of drugs at a population level and the costs of producing a particular drug are relatively constant, prices paid to drug manufacturers vary by insurance company and PBM (Park et al., Reference Park, Raza, George, Agrawal and Ko2017; Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Kim, Pope, Graff, Wilkinson and Neumann2018a, Reference Chambers, Pope, Bungay, Cohen, Ciarametaro, Dubois and Neumann2018b). Whether a drug is considered first step, or most cost effective, in insurance policy step-therapy protocols changes not with the efficacy or cost of a drug, but with the rebates, fees and discounts negotiated among the PBMs, drug manufacturers and insurers. Pharmaceutical companies may use these programs to access patients with favorable pricing or no- or low-cost coupons with the promise or history of high volume that in turn increases rebates to the insurer and associated PBMs. Those negotiations determine the amount that will be paid for a drug and, thereby, are likely to drive the choice of what is the first-step drug in an insurance company policy. This also partially explains why what is considered the first-step fail-first drug differs among insurers and PBMs. It also explains why an individual patient could be made to fail the same first-step drug more than once (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Kim, Pope, Graff, Wilkinson and Neumann2018a, Reference Chambers, Pope, Bungay, Cohen, Ciarametaro, Dubois and Neumann2018b; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Dhruva and Ros2018).

4. Evidence-based therapeutic choices

Scientifically validated pathways can prove efficacy and safety of a drug, allowing the drug choice to rise to a most preferred position for a specific population as a first-line agent and for others to be considered a second- or third-line agent. If two drugs provide similar efficacy and safety, it may be reasonable to consider whichever has lower cost to be the preferable choice. If this methodology was followed, every insurer would offer the same first-step medication for a condition, which is not the case.

In the current health care environment, health care providers, systems and regulatory agencies are all trying to show a positive effect on population health. An individual health care provider does this by treating individuals – offering them best choices for them as an individual. Insurers and PBMs with publicly stated goals of improving population health also have a goal of financial success for shareholders that drive cost-reduction across the board at a disadvantage to individuals who don't fit into the insurer's lowest-cost (to the insurer) group that determines cost-effective population health protocols.

5. Efforts to protect patients with state legislation

5.1 What state legislation provides

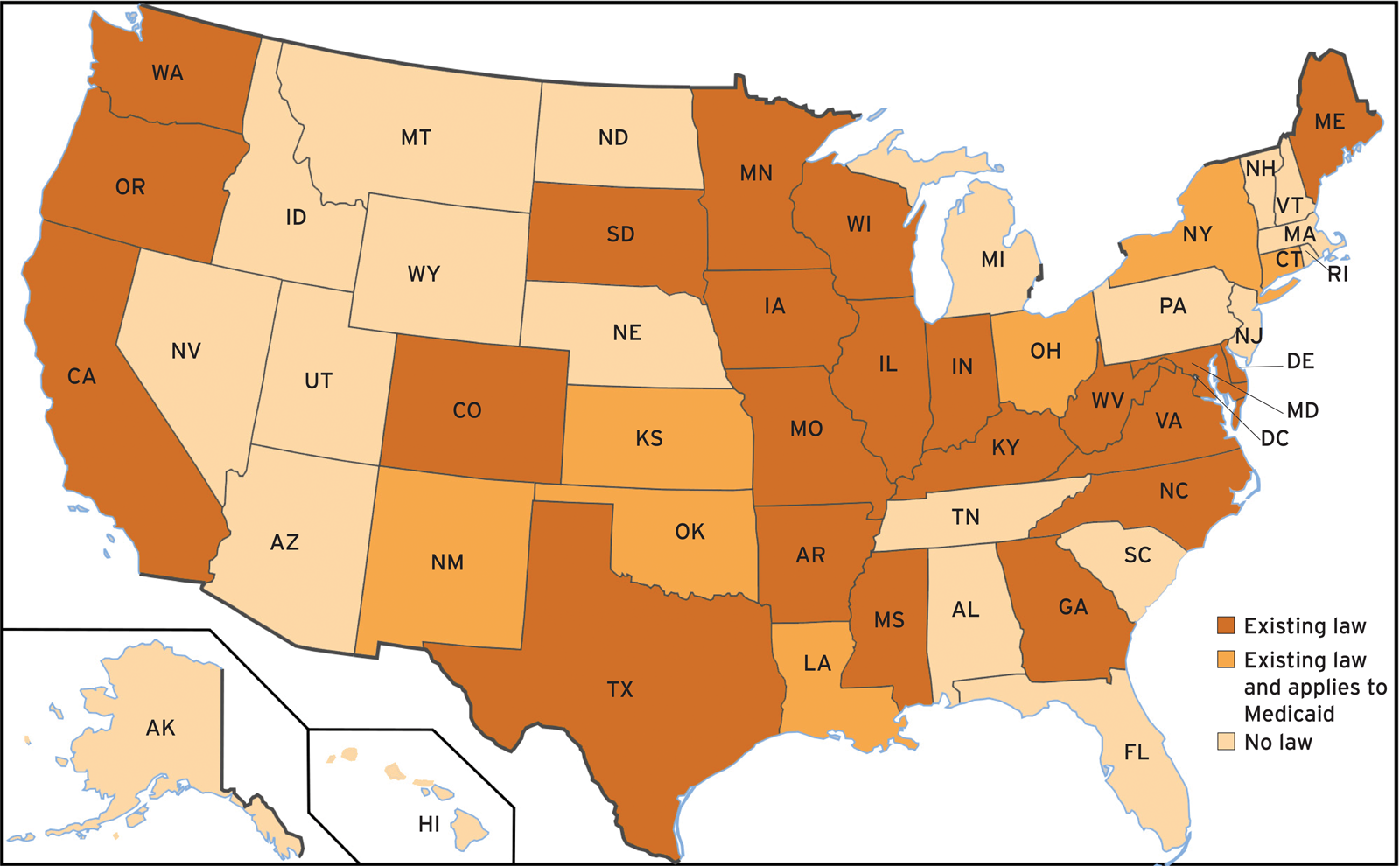

We have conducted an audit of state laws (Appendix A). Although no state prohibits step-therapy protocols by insurers, 29 states have passed laws requiring a process that allows health care professionals to protect their patients from step-therapy protocols with a list of exemptions that insurers are required to accept (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1. Step-therapy laws by state. Note that in Louisiana, South Dakota and Washington, the legislation becomes effective 1 January 2021.

Table 1. Accepted reasons for exemption from step therapy

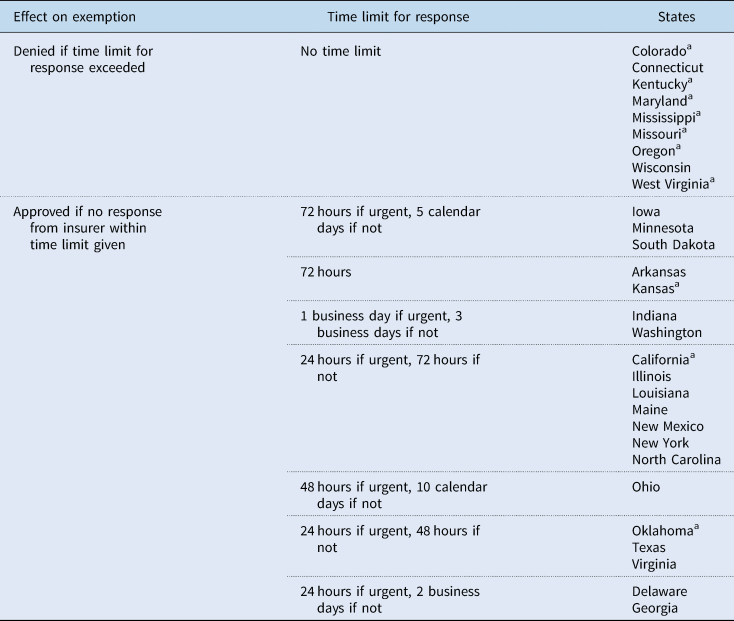

Table 1 shows the primary reasons for requesting an exemption from the step-therapy protocol listed in state laws. Only six states cover all these reasons; California and Oregon cover none, and Missouri and Colorado cover only one. In 10 states, there is no appeal process if an exemption is denied, further weakening these laws. Some state legislation imposes specific time periods within which the insurer must respond. In nine states, however, insurers or PBMs have no obligation to respond, rendering the laws moot. In California and Mississippi, because the law states that step therapy that is not clinically effective shall not last longer than 60 or 30 days, respectively, the law is essentially allowing step therapy for a period of time – during which harm may still occur (Table 2).

Table 2. Effect of exemption request time limits on insurer response

a No appeal of decision possible.

The weakest step-therapy protocol state laws are in California, Oregon, and Missouri. California provides an appeal process that is the same as a prior authorization appeal. Oregon's law says that plans create clear clinical criteria for step-therapy protocols and provide documentation that a practitioner must submit to determine appropriateness of step therapy. Missouri's law provides exemption only if the patient has already tried and failed the drug considered first-step by their insurance company.

Ohio has the strongest step-therapy law for a number of reasons. The law touches on most of the primary reasons for exemption from step therapy and clearly outlines the exemptions process and the appeals process. The law places time restraints on the payer for both the exemptions and appeals process, therefore increasing the chance of approval of exemption. The Ohio law even gives the ability to appeal further than the typical appeals process in other states. It is mentioned that violations of the law will be considered unfair and deceptive practice. The Ohio law, spearheaded by the American Academy of Dermatology, also applies to Medicaid and therefore covers a significant portion of the state population.

In 2020, Louisiana passed new legislation to add protections to the previous step-therapy law passed nearly a decade before. The new law includes all seven of the common exemption reasons. Insurers are now required to respond to exemption requests in a timely manner or the request is automatically granted, whereas before there was no limit. Providers are also now able to appeal an exemption decision. This new legislation provides protection for more than just Medicaid and strengthens the previous law after a decade without these protections.

No step-therapy laws carry exemptions over on an annual basis, which means patients are faced with failing multiple times on the same drug. Typically, if a patient stays on the same insurance plan after an exemption, step therapy is not repeated, but there are no laws that prevent this, and repeating fail-first therapies will likely have to be repeated if

• a covered employer changes insurer or PBM,

• a covered employee changes jobs, even if the new job has the same insurer and/or PBM,

• a covered employee moves into a different tier of the Affordable Care Act or

• a covered employee leaves a job and utilizes the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA).

5.2 Who is protected by state legislation?

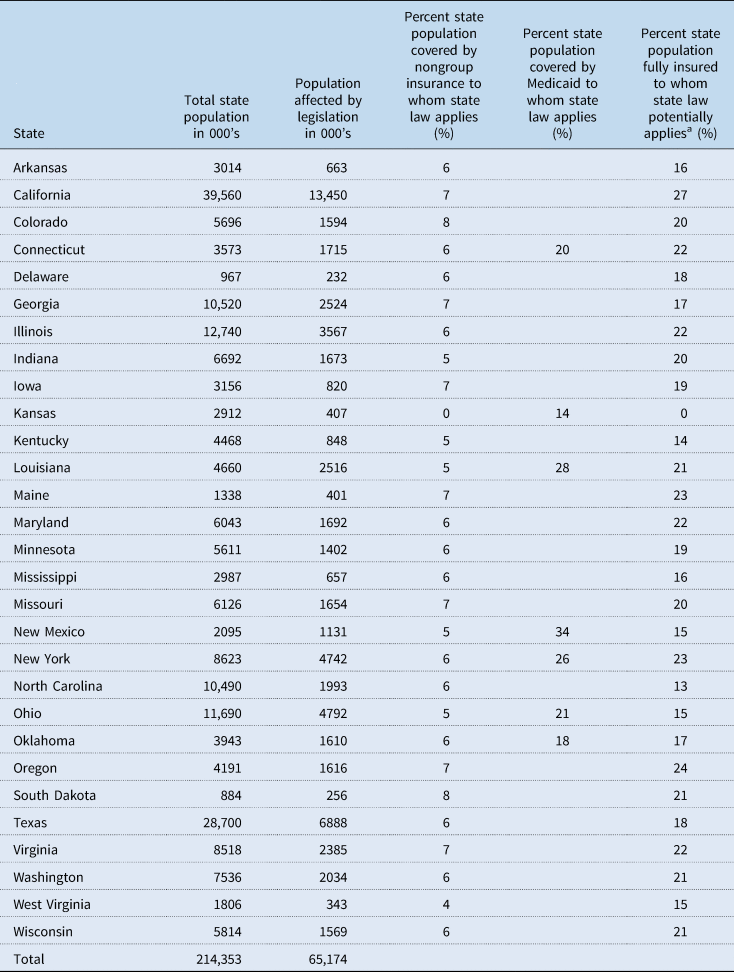

In seven states the legislation has protections for Medicaid beneficiaries (Table 3) benefitting patients in the hardest-to-treat category. However, the lack of procedures to enforce the law, rigid policy requirements, onerous paperwork and work requirements for Medicaid diminish this benefit.

Table 3. Percent of state population covered by state step-therapy regulatory law

a Extrapolated from available data (MEPS, 2018) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019a).

For most states, step-therapy legislation applies to state-regulated health plans (in other words, nongroup coverage and some fully insured employer plans). Nongroup insurance, which includes policies purchased directly from an insurance company either as policyholder or as a dependent, covers fewer than 10% of the U.S. population and not all of these individuals are protected by state laws regarding step therapy. They may live in states with no or weak/unenforceable step-therapy laws, or they may unknowingly purchase plans from companies in a state other than where they reside, which therefore are not subject to their state's step-therapy laws.

Most people covered by employer-provided health plans are also not protected by state legislation regulating step-therapy because of restrictions under the federal Employee Retirement Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). ERISA preempts state insurance regulations, meaning that employers with self-funded medical benefits are not required to comply with state insurance laws that apply to health plan administrators. The ERISA ‘savings clause’ allows states to regulate the terms and conditions of health insurance (e.g. policy benefits or market operations). Under the ‘deemer clause’, however, states may not regulate plans that are self-insured. Therefore, state step-therapy laws do not apply to these plans, which are used by the majority of insured individuals in the United States. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized that this creates two types of employer-sponsored health plans for which fully insured plans are subject to state oversight and self-insured plans are beyond state jurisdiction (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2020).

Almost all large employers are self-insured (86% of those with over 5000 employees), and about half of individuals in the United States are covered by self-insured employer insurance (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019a). An increasing number of businesses are choosing self-insured plans, suggested by benefits managers as a cost-saving measure, notably because of not having to provide state-mandated benefits (Bazar, Reference Bazar2017). According to a 2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey, 61% of covered workers in the United States are enrolled in a self-funded plan (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019b). Thus, for the majority of workers and their families, employer-sponsored plans are self-insured plans, making step-therapy reform at the state level ineffective for these millions of people.

Although fully insured plans must comply with some ERISA requirements, they are primarily subject to state regulations. This is because although the plan itself is regulated by ERISA, the insurance product that the plan sponsor purchases in a fully insured plan can be regulated by states and therefore influence benefits (Borzi, Reference Borzi2002). Therefore, state step-therapy laws should protect fully insured employer-sponsored plans.

Fully insured employees, however, who ordinarily would be covered by state step-therapy legislation (unless specifically excluded as in Kansas) may not be protected because the company they work for isn't headquartered in the state where they reside (territorial prerogatives). Fully insured plans are subject to the laws in the state where the plan is issued, not necessarily where the beneficiary resides. It is unknown whether these individuals are protected by the laws limiting step therapy in the state where the company is domiciled or not protected because there is no law in the state where they work. This is likely to occur in the northeastern United States, where states are clustered, and many people work in another state. It is also likely for individuals employed by large companies with employees all over the country that are headquartered in a state with no protections. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that everyone in a fully insured plan is protected by state laws limiting step therapy.

Available data to assess this are limited, and this may be why the Kaiser Family Foundation data do not distinguish between fully insured and self-insured plans. Nevertheless, we extrapolated data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance/Component to assess what proportion of individuals within each state are protected by step-therapy legislation of that state (Table 3). We found the state with the potentially highest proportion of people protected (~33.6%), California, is one of three states with the weakest step-therapy laws, making the number of people covered moot, especially because it could be further reduced by territorial prerogatives (see Section 5). Another state with step-therapy laws, Kansas, specifically excludes fully insured employees. Thus, adding in people who are fully insured to those protected by state step-therapy laws does not change the conclusion that these laws protect only a minority, usually small, of a state's population.

Furthermore, if reliable data and information are not available to research, it is also not available to patients, who will also not know whether they are protected by the laws. It is also unlikely that insurers or PBMs will volunteer this information, making the practical application of these laws nearly impossible.

5.3 Overall effectiveness and future of state legislative efforts

In the 22 states that have passed step-therapy legislation that does not apply to those on Medicaid, at most 19–34% of the state's population are protected by these laws. For state laws limiting step therapy to have the most reach, each state needs its own law that mentions both Medicaid and private health insurance plans. Most states, as of now, only contemplate one or the other, and only seven states have protections that cover both those insured by Medicaid and private insurance. In the seven states where Medicaid is subject to step-therapy laws, 14–55% of people could be protected from the potential harm of step-therapy protocols. As discussed, the number of people who are truly protected is significantly lessened by the lack of means to enforce these laws, lack of an appeals process and lack of time limits for response that are a part of the laws in many states.

Efforts to pass laws addressing step-therapy protocols in the 21 states without such laws are likely to become more difficult. The 15 that have legislatures and/or executive branches controlled by Republican majorities are generally not predisposed to favor patient-centered legislation. Many want to take away or reduce state involvement in health care. Of the other seven, only four have Democratic control of both executive and legislative branches.

As the health care debate continues, positions become more entrenched and ideologic reasons for supporting step therapy, including free- or open-market positions and a priority on reducing per capita health care costs become more difficult to counter. Because the United States continues to have the highest health care costs with the worst outcomes among industrialized countries, the population health argument that justifies step therapy for the sake of cost-effectiveness despite the potential harm to people with higher health care needs has also become further entrenched.

Arguments from legislators who oppose regulation of step therapy have linked step-therapy reforms to single patient coalitions and/or single pharmaceutical companies funding those groups' efforts. This has also created a backlash in the media with major media outlets suggesting patient groups are advocating for their pharmaceutical funders and not their individual members (Kopp et al., Reference Kopp, Lupkin and Lucas2018; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Bai, Karas and Anderson2019). This backlash has put patient group coalitions in a defensive position. Similarly, working with public relations companies and coalitions can create grass-top organizations that give the perception of community-based support without actual community involvement of true grass-root organizations. This model further opens advocacy groups to the backlash described, undermining important patient-centered work, including step-therapy reform.

In summary, the backlash against patient-advocacy groups, conservative legislative bodies in states without step-therapy regulation, and arguments for free-market population-focused efforts to control health care costs all make passing reforms in the remaining 21 states without step-therapy regulation unlikely, making the value of efforts to this end questionable. The fact that so few individuals are affected in those states that have passed step-therapy regulatory controls also makes the benefits of state legislation vs the expense of organizing to support this legislation questionable.

6. Federal legislation efforts

In the 116th Congress (2019–2020), Representative Brad Wenstrup (R Ohio 2nd) and Representative Raul Ruiz (D California 36th), who is a physician, introduced H.R. 2279, a step-therapy reform bill, into the U.S. House of Representatives. The bill's short title is the Safe Step Act. Its official title is ‘To amend the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 to require a group health plan (or health insurance coverage offered in connection with such a plan) to provide an exceptions process for any medication step-therapy protocol, and for other purposes’. The bill is modeled after the Ohio state legislation. On 10th April 2019 the bill was introduced in the House and referred to the House Committee on Education and Labor. In the House of Representatives, the bill has 150 cosponsors, including the original cosponsors Ruiz and Wenstrup. The breakdown is 99 Democratic cosponsors and 51 Republican cosponsors (116th Congress of the United States, 2019).

On 25th September 2019 Senator Lisa Murkowski (R Alaska) introduced The Safe Step Act (S. 2546) in the Senate, and it has been referred to the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee. In the Senate, the bill has 16 cosponsors, seven of whom are Democrats, eight of whom are Republicans and one of whom is an Independent.

Previously, during the 115th Congress (2017–2018), Representatives Ruiz and Wenstrup introduced H.R. 2077, the Restoring the Patient's Voice Act of 2017. Its official title was ‘To amend the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 to require a group health plan (or health insurance coverage offered in connection with such a plan) to provide an exceptions process for any medication step-therapy protocol, and for other purposes’. The bill had 88 cosponsors, including the original cosponsors. The breakdown was 51 democratic cosponsors and 37 republican cosponsors (115th Congress of the United States, 2019). Since being introduced on 6th April 2017 and referred to the House committee on Education and the Workforce, no further actions have been taken.

6.1 What the safe step act entails

The Safe Step Act would require group health plans or related health insurance coverage to provide a clear exemptions process for any step-therapy protocol. The Safe Step Act also would provide expedited approval if a first-step medication was contraindicated, expected to be ineffective, known or likely to cause an adverse reaction in the individual, not in the best interest of the individual or already being used in a patient who is stable. The Safe Step Act would require an insurer to respond within three days of an exemption request, or in the case of an emergency request, within 24 hours.

The Safe Step Act would not completely end step-therapy practices; this allows step-therapy protocols to still be used for cost-effective prescribing to promote population health while protecting individual patient's situations and needs to prevent harm. If passed, the federal bill works with the state laws to provide protection for all people on employer plans by amending ERISA. This type of protection would apply to a much larger proportion of the population than the existing state legislation regulating step therapy because the majority of people in the United States are covered by employer plans. State step-therapy legislation would fill in the gaps in the federal legislation by providing protections for the remainder of the population, including nongroup beneficiaries.

6.2 Chances of passage

Chances that the Safe Step Act will pass are low, although it has bipartisan cosponsors and support. The bill was sent to only one committee, which is often promising for movement as compared with being sent to many committees. A senate bill was introduced in September 2019, which is an important sign of support for legislation to regulate step therapy.

Although it is unlikely that the Safe Step Act will be passed quickly, there is still hope for the future. Most cosponsors were retained in the transition from the first to the second bill, indicating continued support. If advocacy efforts build more support in Congress, the chances for a bill eventually being passed will increase.

7. Recommendations

Even if a federal bill was passed, there are no guarantees that it would cover the minority of people covered by state statutes. For this reason, we recommend continued commitment to step-therapy reform and regulation as well as auditing of current legislation to make sure that it is serving patients' best interests in an evolving health care landscape. Although we question the value of committing significant resources to step-therapy regulation and reform at the state level, continued support for groups pursuing that legislation is important, if only for the sake of letting those involved know they are not abandoned by larger efforts.

We also recommend resources be committed for rule-making assistance for existing state laws, almost all of which lack rules governing implementation and enforcement, significantly diminishing most of the law's utility. Experts should be deployed to assist states in creating a relevant application of laws to serves patients.

Education of patients, health care professionals, social workers, employers and state government administrators alerting all audiences to existing laws, provisions and penalties is needed to keep legislation from becoming unknown and unused. Individual patients, especially those with chronic disease, have the fewest resources compared with other stakeholders to fight for themselves to ensure high-quality health care at an affordable price. We recommend creating or reinforcing infrastructure that makes it unnecessary for those with chronic illnesses to devote any of their already limited resources to fight for the drugs they and their physicians have determined they need.

We recommend the use of model legislation, such as that created by the Physicians Research Institute with templated research, legislator communications and media outreach (Physicians Research Institute, 2019). This could provide legislators with what they need to pass effective step-therapy regulatory legislation and also reduce the cost of advocacy for state laws in those states that do have them yet. Lowering the cost of legislation is critical and model legislation is a priority. Working closely with national organizations such as the National Conference of State Legislators and the National Academy for State Heath Policy to help achieve the above objectives is potentially an efficient method of educating lawmakers, answering questions and streamlining patient involvement in lawmaking.

Infrastructure to collect and audit compliance and patient benefit is also needed. We have to know the efficacy of the legislation and whether enforcement is necessary. It should be determined if penalties are sufficient to curtail gaming the system and disadvantaging patients, whether patients know about their rights and can easily access the law's provisions, as well as whether health care professionals and social workers are able to advocate easily for patients in need.

Employer education may help convince employers of a larger role they can take in ensuring step-therapy policies of insurers and PBMs they contract with do not harm individuals. Employers could also advocate for step-therapy legislation in states that don't have it, which is especially relevant for multistate companies that have to deal with conflicting laws. Such efforts have been initiated in conjunction with the National Alliance of Health care Purchaser Coalitions, Global Health care Resources, George Washington University's Institute for Corporate Responsibility and biopharmaceutical companies (National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions, 2019). Engaging with employers may be a more direct way to reach businesses committed to healthy productive people, create employee groups who can advocate for themselves and recruit lobbying and government relations expertise to engage in rulemaking as well as passage of legislation at both the state and federal levels. Engaging with populations who pay health insurance premiums and have a common goal of sustaining high-quality health care at reasonable prices may be a more direct way of achieving patient-centered results.

Finally, we recommend engaging in patient-centered medical research projects. For example, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Patient Partners Research Network can create patient-reported outcomes data that provide an objective assessment of patient benefits related to step therapy. Credible data are likely to help improve existing laws and supports legislative efforts in states without them.

Conflict of interest

Louis Tharp and Zoe Rothblatt have no personal disclosures to make. The Global Healthy Living Foundation receives funding from pharmaceutical companies, nongovernment organizations and private foundations which have opinions and business strategies for and against step therapy legislation.

Appendix A: Step-therapy laws by state

Arkansas: Senate Bill 665, An act to clarify certain provisions of the prior authorization transparency act; to limit retrospective denials of authorized services; to authorize benefit inquiries; to exempt authorized services from audit recoupment; to declare an emergency and for other purposes.

California: Assembly Bill No. 374, An act to add Section 1367.244 to the Health and Safety Code, and to add Section 10123.197 to the Insurance Code, relating to health care coverage.

Colorado: Senate Bill 17-203, Concerning the prohibition against a carrier requiring a covered person to undergo step therapy, and, in connection therewith, requiring coverage for a prescribed medication that is part of the carrier's medication formulary.

Connecticut: Senate Bill No. 394, An act concerning requirements for insurers' use of step therapy.

Delaware: House Bill 105, An act to amend title 18 of the Delaware code relating to health insurance contracts.

Georgia: House Bill 63, An act to amend Chapter 24 of Title 33 of the Official Code of Georgia Annotated, relating to insurance generally, so as to require health benefit plans to establish step-therapy protocols; to provide for a step-therapy exception process; to provide for definitions; to provide for statutory construction; to provide for applicability; to provide for related matters; to repeal conflicting laws' and for other purposes.

Illinois: House Bill 3549, An act concerning regulation.

Indiana: Senate Enrolled Act No. 41, An act to amend the Indiana Code concerning insurance.

Iowa: House File 223, An act relating to the use of step-therapy protocols for prescription drugs by health carriers, health benefit plans, and utilization review organizations, and including applicability provisions.

Kansas: House Substitute for Senate Bill No. 402, An act concerning public assistance; relating to cash assistance, food assistance, medical assistance and child care subsidies; eligibility; recovery of assistance debt; verification of identity and income; fraud investigations; work requirements; lifetime benefit limits; removing certain limitations under the electronic claims management system; amending K.S.A. 39-719b an K.S.A. 2015 Supp. 39-702, 39-709 and 39-7,121 and repealing the existing sections.

Kentucky: Senate Bill 114, An act relating to step therapy.

Louisiana: House Bill No. 393, An act to enact Part XI of Chapter 3 of Title 46 of the Louisiana Revised Statutes of 1950, to be comprised of R.S. 46:460.31 through 460.35, relative to the medical assistance program; to provide relative to managed care organizations which provide health care services to medical assistance program enrollees; to provide relative to prescription drugs; to provide for prepaid coordinated care network pharmaceutical and therapeutics committees; to provide for a standard form for the prior authorization of prescription drugs; to provide for certain procedures relative to step-therapy and fail-first protocols; to provide for promulgation of rules; to provide for exemptions and to provide for related matters.

Maine: House Bill 1009, An act to provide for Maine patient facing step therapy.

Maryland: House Bill 1233, An act concerning health insurance – step-therapy or fail-first protocol.

Minnesota: House Bill 3196, A bill for an act relating to health insurance; establishing a step-therapy protocol and override for prescription drug coverage; proposing coding for new law in Minnesota Statutes, chapter 62Q.

Mississippi: Senate Bill No. 2737, An act to provide for the step-therapy or fail-first protocols by a prescribing practitioner under certain circumstances; and for related purposes.

Missouri: House Bill No. 2029, An act to amend chapter 376, RSMo, by adding thereto three new sections relating to step therapy for prescription drugs.

New Mexico: Senate Bill 112, An act relating to health coverage; enacting new sections of the health care purchasing act, the public assistance act, the New Mexico insurance code, the health maintenance organization law and the nonprofit health care plan law to establish guidelines relating to step therapy for prescription drug coverage.

New York: Bill No. A02834D, An act to amend the insurance law and the public health law, in relation to expedited utilization review of prescription drugs.

North Carolina: Senate Bill 361, An act to enact the psychology interjurisdictional compact, allow licensed marriage and family therapists to conduct first-level commitment examinations, eliminate redundancy in adult care home inspections, ensure the proper administration of step-therapy protocols and clarify the use of coronavirus relief funds allocated to the North Carolina community health center association.

Ohio: Substitute Senate Bill Number 265, An act to amend sections 173.12, 341.192, 1739.05, 1751.01, 3702.30, 3712.06, 3712.061, 3963.01 and 5167.12 and to enact sections 1751.91, 3901.83, 3901.831, 3901.832, 3901.833, 3923.89, 5164.14, 5164.7512, 5164.7514 and 5167.121 of the Revised Code to permit certain health insurers to provide payment or reimbursement for services lawfully provided by a pharmacist, to adopt requirements related to step-therapy protocols, and to recognize pharmacist services in certain other laws.

Oklahoma: Senate Bill 509, An act relating to health insurance; defining terms; requiring insurers to use clinical practice guidelines for developing step-therapy protocol; requiring insurers to provide process to request a step-therapy exemption; requiring step-therapy exception process be posted online’ requiring insurer to grant step-therapy exception in certain circumstances; requiring insurers to permit appeal of step-therapy exception decision’ establishing timeline for response to step-therapy exception; authorizing automatic granting of exception in certain circumstances' requiring insurer to authorize coverage and dispensation of drugs in certain situations; providing construing provisions; authorizing Insurance Department and Health Care Authority to promulgate rules; providing for codification; and providing an effective date.

Oregon: House Bill 4013, An act relating to prescriptions; creating new provisions; amending ORS 475.185 and 475.188; and declaring an emergency.

South Dakota: Senate Bill 155, An act to provide for step-therapy protocol regarding certain prescription drugs.

Texas: Senate Bill No. 680, An act relating to step-therapy protocols required by a health benefit plan in connection with prescription drug coverage.

Virginia: H 21216, An act to amend the code of Virginia by adding a section numbered 38.2-3407.9:05, relating to accident and sickness insurance; step-therapy protocols.

Washington: House Bill 1879, An act relating to regulating and reporting of utilization management in prescription drug benefits; adding new sections to chapter 48.43 RCW; and creating a new section.

West Virginia: House Bill 2300, A bill to amend the Code of West Virginia, 1931, as amended, by adding thereto a new section, designated §33-15-4o; to amend said code by adding thereto a new section, designated §33-16-3aa; to amend said code by adding thereto a new section, designated §33-24-7p; to amend said code by adding thereto a new section, designated §33-25-8m; and to amend said code by adding thereto a new section, designated §33-25A-8o, all relating to regulating step-therapy protocols in health benefit plans which provide prescription drug benefits; providing for an exception from the protocols; setting out criteria for the exception; providing for an effective date; and setting out exclusions.

Wisconsin: Senate Bill 26, An act to create 632.866 of the statutes; relating to: step-therapy protocols for prescription drug coverage and requiring the exercise of rule-making authority.