Introduction

Persistent pain occurs in 45%–85% of adults over the age of 65 (Jakobsson et al., Reference Jakobsson, Hallberg and Westergren2004) often with serious impact on function and wellbeing (Gianni et al., Reference Gianni, Ceci, Bustacchini, Corsonello, Abbatecola, Brancati, Assisi, Scuteri, Cipriani and Lattanzio2009). Pain treatment and management are important contributors to the quality of life in older people and facilitate participation in valued activities. Help the Aged (Kumar and Alcock, Reference Kumar and Alcock2008), a UK charity advocating for older people, reported the views of those living with pain and emphasised the pervasive nature pain has on all areas of life, including other medical conditions, mental health, relationships, opportunities to socialise, and identity all of which are reported elsewhere (Holloway et al., Reference Holloway, Sofaer and Walker2000; Reyes-Gibby et al., Reference Reyes-Gibby, Aday and Cleeland2002; Drummond, Reference Drummond2003; Closs et al., Reference Closs, Staples, Reid, Bennett and Briggs2009).

While common, pain in older people appears to be under-recognised and under-treated (Cavalieri, Reference Cavalieri2002). Although older people are more likely to experience pain than younger people (Fayaz et al., Reference Fayaz, Croft, Langford, Donaldson and Jones2016), older people are less likely to receive effective and sufficient help for their pain (Makris et al., Reference Makris, Higashi, Marks, Fraenkel, Sale, Gill and Reid2015) partly due to inadequate assessment. Pain assessments are disproportionately overlooked for older people, with some physicians perceiving pain as a normal part of ageing (Niemi-Murola et al., Reference Niemi-Murola, Nieminen, Kalso and Pöyhiä2007). Additionally, pain in older people often presents ‘atypically’, for example, poorly localised and lasts longer compared to younger counterparts (Robinson, Reference Robinson2007). Given that pain assessments as well as physician training in pain management are based on studies of younger (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Patijn and Lamé2007), often male (Samulowitz et al., Reference Samulowitz, Gremyr, Eriksson and Hensing2018), identifying and recognising pain in older people can be challenging. Furthermore, older people are less likely to vocalise their pain, experience greater self-doubt around reporting it, and may use different words (e.g., ‘sore’ or ‘aching’) to describe pain compared to younger people (Collett et al., Reference Collett, O’Mahoney, Schofield, Closs and Potter2007).

The issues around assessing pain are exacerbated in residential and nursing homes where access to physicians is often less frequent than in a community setting (Ferrell, Reference Ferrell2004; Hunnicutt et al., Reference Hunnicutt, Ulbricht, Tjia and Lapane2017). Additionally, residents often have cognitive and/or communication difficulties (Frampton, Reference Frampton2003), which is problematic given that the majority of widely used and standardised pain assessments rely on self-reporting.

Pain management also presents age-related issues. The ageing process per se increases sensitivity to both the intended and unintended effects of pain medication (Beyth and Shorr, Reference Beyth and Shorr2002). Multi-morbidity and polypharmacy, both common among older people (Wehling, Reference Wehling2009), can introduce complex drug interactions that exacerbate other health conditions (Marengoni and Onder, Reference Marengoni and Onder2015). For example, drugs providing pain relief can negatively affect other health conditions such as gastritis. Furthermore, changes in metabolism in later life and the long-term effects of using pain medication over decades (Alam et al., Reference Alam, Gomes, Zheng, Mamdani, Juurlink and Bell2012) need to be factored into prescribing decisions (Gloth, Reference Gloth2001). Therefore, as well as under-treatment of pain, over-prescription of strong pain killers, based on the doses required for younger people, larger than those required for older people, adds to the complexity of inappropriate pain management for older people.

Inappropriate prescription of opioids for older people appears particularly prevalent (West and Dart, Reference West and Dart2016; Fain et al., Reference Fain, Alexander, Dore, Segal, Zullo and Castillo-Salgado2017). Initiation of strong opioids without first treating pain with simple analgesics or weak opioids has been identified in one-third of community-dwelling older outpatients (Gadzhanova et al., Reference Gadzhanova, Bell and Roughead2013). Prescribing strong opioids is not only more prevalent for older people, but also increasing at the fastest rate in this age group (Roxburgh et al., Reference Roxburgh, Bruno, Larance and Burns2011). Häuser et al. (Reference Häuser, Bock, Engeser, Tölle, Willweber-Strumpf and Petzke2014) compared the consumption of prescribed opioids for non-cancer pain in 2014 in Australia, Canada, Germany, and the USA and found ‘signs of an opioid epidemic’ (page e-599/p1) in North American and Australian but not Germany and attributed this not to opioids per se, but how they are used, ‘without appropriate indication, appropriate precautions, and with excessive doses, often as a monotherapy’ (page e-599/p10).

This trend is problematic given the international ‘opioid crisis’, or increasing rates of opioid addiction and opioid-related mortality (Dhalla et al., Reference Dhalla, Persaud and Juurlink2011). Opioid-based pain management has a specific impact on older people who may be experiencing falls, memory problems, and incontinence all of which can be exacerbated by opioids (Gianni et al., Reference Gianni, Ceci, Bustacchini, Corsonello, Abbatecola, Brancati, Assisi, Scuteri, Cipriani and Lattanzio2009; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Blundell, Gladman and Masud2010; Morley, Reference Morley2017). The majority of findings on changes in opioid prescribing for older people come from outside the UK and little is known about the UK-specific context or if the trends in other countries are mirrored in the UK.

Most health and care services in the UK are commissioned by groups of GP Practices known as Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and our local CCG (Canterbury and Coastal) provided the catalyst for this study. There is little UK literature concerning not only what the trends of inappropriate opioid prescribing for older people are, but also why inappropriate prescribing occurs in this age group (and compared to younger people). This scoping review aimed to ascertain what factors influence opioid prescribing as non-palliative pain-management medication for older people; the results will be used to inform practice development and training within the CCG.

Methods

A scoping literature review is a comprehensive and systematic approach that allows for a broad research question and incorporates all sources, including grey literature, compared to a standard systematic review that focuses on a ‘narrow range of quality assessed studies’. We used Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) framework as it offers a rigorous approach suited to identifying gaps in existing literature (Reyes-Gibby et al., Reference Reyes-Gibby, Aday and Cleeland2002) and reviewing areas that are complex and broad. It comprises five stages: identifying the research question (as above); identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; and collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

Identifying relevant studies

The review was guided by the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria

1. Literature, including all study designs and publication types, from Peer-Reviewed Journals from January 1990 to September 2017

2. Grey literature (e.g., policy papers) from January 1990 to September 2017

3. Literature in English language only (resource restrictions meant that translation services could not be used)

4. Papers that involve older adult participants (i.e., participants aged 65 and older) regardless of setting (i.e., community-dwelling older people as well as those living in care/nursing homes), or looked at external perceptions of older adult pain management

5. Papers on opioid prescribing for pain management for older people

Exclusion criteria

1. Bachelor and Masters dissertations; unpublished doctoral theses

2. Papers specifically focusing on opioid use, rather than prescribing (studies focusing on use/misuse of opioids were outside of the scope for this review, which concerned factors influencing prescribing of opioids)

3. Papers specifically assessing methodological instruments or approaches (e.g., efficacy of risk minimisation tools in opioid prescribing)

4. Papers on palliative or end-of-life care

5. Papers on opioids as substitution (e.g., for heroin) rather than pain management

6. Guidelines addressing how clinicians should prescribe, rather than what affects current prescribing

A conceptual diagram was developed to focus the literature search on the intersection of 4 topics (see Area 5 of Figure 1). The search terms were developed for electronic databases (PubMed, EBSCO Host, and Google Scholar). The UK Drug Database, a general practitioner and a palliative care clinician were consulted to ensure no specific types of opioids were excluded from the search. The search terms/keywords were:

‘opioid’ or ‘opiate’ or ‘oxycodone’ or ‘oxycontin’ or ‘fentanyl’ or ‘hydrocodone’ or ‘Co-dydramol’ or ‘hydromorphone’ or ‘meperidine’ or ‘pethidine’ or ‘morphine’ or ‘codeine’ or ‘alfentanil’ or ‘dihydrocodeine’ or ‘diamorphine’ or ‘meptazinol’ or ‘pentazocine’ or ‘papaveretum’ or ‘remifentanil’ or ‘buprenorphine’ or ‘tramadol’ or ‘tapentadol’ or ‘dipipanone’ or ‘buprenorphine’ AND

‘older adult’ or ‘older person’ or ‘older people’ or ‘elders’ or ‘elderly’ or ‘geriatric’ AND

‘prescription’ or ‘prescribing’ or ‘prescribed’ AND

‘pain management’ or ‘pain’

Figure 1. The conceptual framework guiding the literature search

Existing systematic reviews were used to identify primary research. Grey literature was identified both within the above searches and by searching the archives of relevant ‘grey’ journals such as Adverse Reaction Research periodical.

Academic and grey literature resulting from the literature search was then screened: first by title and abstract, and then by reading the full text to determine if inclusion/exclusion criteria were met. A data extraction tool was used for full-text review. Reference lists of reviewed articles were also scanned of relevant papers.

Two authors (R.M. and V.A.) carried out study selection. At each stage of selection, the authors first worked together to establish a consistent approach, and then independently. Sources were categorised into those that should be included in the final synthesis, those that did not meet the inclusion criteria, and those where both researchers were uncertain. A third researcher (P.W.) independently reviewed papers where the primary reviewers remained uncertain.

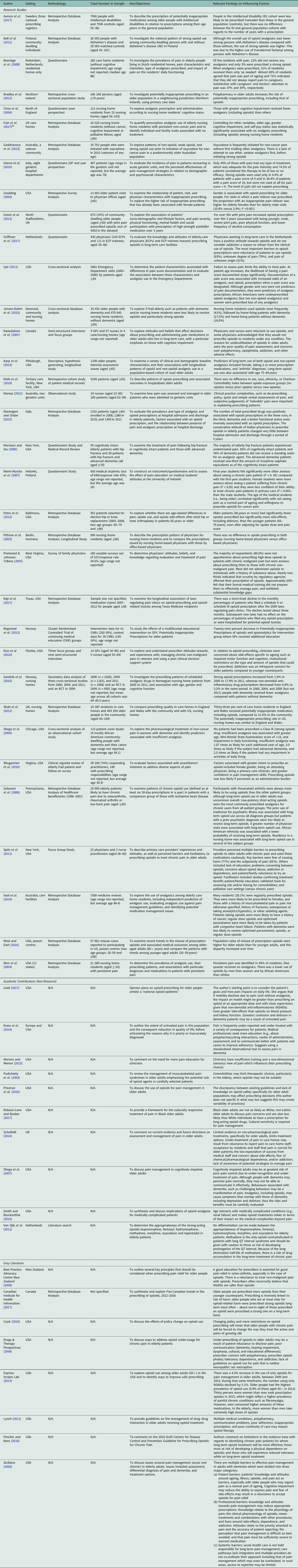

Papers meeting selection criteria were then summarised in Table 1, extracting specifically study setting, methodology, sample characteristics, study aims/objectives, and findings informing which factors influenced opioid prescribing for older people. These sources were further categorised by (1) whether the source suggested that opioids were being underprescribed, overprescribed, demonstrated complex prescription patterns, or had no explicit stance; (2) factors associated with different prescribing trends (e.g., higher versus lower opioid prescribing); and (3) whether influencing factors were patient characteristics, prescriber characteristics, or policy/system factors. A narrative framework (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) was used to synthesise the findings, analyse knowledge gaps, and identify areas of consensus or disagreement.

Table 1. Studies reporting factors influencing opioid prescribing for pain-management in older people

Findings

Study selection

The initial search identified 626 papers with 360 remaining once duplicates were removed. These papers were screened by title and abstract; 116 were excluded, leaving 244 to assess by reading full text. Nine of the 116 excluded sources were non-English language. Figure 2 summarises the process.

Figure 2. Screening flowchart

Of the 244 sources selected for full-text screening, 181 were excluded including 10 where full-text could not be obtained by institutional subscriptions and/or contacting the author. The full-text articles were categorised according to type: research (170), grey literature (47), and opinion pieces (27). Each reviewer assessed articles from all categories to ensure a consistent approach.

The authors identified 14 systematic reviews but none addressed the same question as to the current scoping review. We screened these for relevant primary sources of which all but one were duplicates, and the remaining one was later removed as it did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Sixty-one remaining articles were included for data extraction using a data extraction tool to ensure a systematic approach. A further 10 sources were excluded. A final set of 53 sources was included in the scoping review, consisting of 35 research papers, 10 opinion papers, and 8 grey literature sources.

Charting the data

Key items from each source were charted using a uniform approach and including author, setting/country, methodology, sample size, aims/objectives, and key findings (Table 1). Sources were categorised by the type of research; then papers from academic journals that did not include primary research such as theoretical and opinion papers; and lastly, grey literature. All sources were coded according to whether the source suggested that opioids were being underprescribed, overprescribed, demonstrated complex prescription patterns, or had no explicit stance.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

A substantial proportion of papers (n = 23, 43%) suggested that opioids were being under-prescribed for older adult pain management. However, the patterns diverged depending on the source. While the same proportion of research papers (40%) and opinion papers (40%) suggest under-prescribing is an issue, this figure was much higher in the grey literature (63%; grey literature was comprised predominantly of opinion pieces in practitioner-oriented non-academic periodicals). Overall, less than a quarter of papers identified over-prescribing as an issue, with no opinion papers addressing the over-prescription of opioids (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Author stance on prescribing overall and based on the source type

Factors that were associated with prescribing patterns were categorised according to whether they were patient-related, prescriber-driven or system-driven. Table 2 demonstrates that patient factors including age, gender, race, and cognition appeared to influence prescribing decisions by physicians. However, prescriber factors were also important and included demographic characteristics such as the age of the prescriber themselves; attitudes towards the use of opioids, abuse/dependency, and on pain per se; and aspects of casework such as the number of contacts with the same patient. Policy/system factors were set in the context of the changing policy landscape over the last three decades. A key factor was funding criteria for medical care, particularly in the USA. However, system factors were rarely captured and seldom discussed.

Table 2. Factors influencing opioid prescribing for older adults by ‘factor source’

The findings were also categorised as to whether the factors were associated with under-prescribing of opioids for older adult pain management, over-prescribing had no apparent effect or the findings were contradictory (see Table 3). There was considerable disagreement between some sources, for example, while three studies found that women were prescribed more opioids than men, one study found the reverse and another that gender had no effect. This demonstrates that opioid prescribing patterns are highly contextual depending on the setting, the period in time, and the interplay with other factors.

Table 3. Factors influencing opioid prescribing for older adults by prescribing trend

Discussion

The scoping review has identified a current imbalance in the literature exploring factors that influence opioid prescribing for older people for regular pain management (see Figure 4). Quantitative studies are more common, most often including secondary data analysis of prescribing databases. Research is also mainly descriptive rather than experimental, with a couple of notable exceptions (Shugarman et al., Reference Shugarman, Asch, Meredith, Sherbourne, Hagenmeier, Wen, Cohen, Rubenstein, Goebel, Lanto and Lorenz2010; Roxburgh et al., Reference Roxburgh, Bruno, Larance and Burns2011). More is known about what the influencing factors are, rather than why or how they operate. For example, while research shows that the patient’s age plays a role in opioid prescribing, it remains unclear why and how it affects prescriber decision-making. It is, for instance, possible that age is construed by the prescriber as an indication of comorbidities and age-specific risks of opioids (Siciliano, Reference Siciliano2006), or it may stem from a belief that pain is a natural part of ageing (Niemi-Murola et al., Reference Niemi-Murola, Nieminen, Kalso and Pöyhiä2007). Research primarily considering attitudes and beliefs is lacking. Finally, while current research demonstrates that both patient and prescriber characteristics are influential in prescribing decisions, most research comes from the prescriber’s perspective and gives comparatively little attention to the perspectives of patients and carers, for example, their opinions on GP prescribing decisions.

Figure 4. The characteristics of existing research on opioid prescribing for pain relief in older adults

While there are a number of existing systematic reviews in relation to opioid prescribing, these do not address all the intersections of the current review [i.e., looking at (1) influencing factors on (2) opioid prescribing for (3) pain management in (4) older people]. Some reviews have looked at potentially inappropriate prescribing for older people (Cherubini et al., Reference Cherubini, Corsonello and Lattanzio2012; Cullinan et al., Reference Cullinan, O’Mahony, Fleming and Byrne2014), but did not specifically address opioids, while others looked at pain management with any pain medicines (Kaye et al., Reference Kaye, Baluch and Scott2010), or focused on treating a specific subset of pain (e.g., acute pain; Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, Tripp and Halksworth-Smith2017). In the one case of a review looking into opioid prescribing for older people (Huang and Mallet, Reference Huang and Mallet2013), it did not address factors influencing prescribing, but instead informed on best practice around opioid prescribing for older people.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to date combining literature on factors influencing trends in opioid prescribing for older people. The scoping review methodology, which allowed for the inclusion of grey literature and non-research/commentary papers, has also significantly mitigated the issues around publication bias prominent in systematic reviews. This review also prioritised capturing the full scope of knowledge and illuminating knowledge gaps. It benefitted from multiple raters, which involved academics with experience in scoping and systematic reviews, as well as a practitioner (GP) with extensive knowledge of the topic, who reviewed ongoing findings.

Scoping reviews do not rate the quality or level of evidence provided therefore recommendations for practice cannot be graded; the aim is to provide a broad overview and identify gaps in the evidence. This approach avoided favouring academic perspectives over that of practitioners and allowed us to capture differing discourse trends within types of literature, for example, that under-prescribing was discussed more commonly in grey literature compared to academic sources.

A drawback of the review was that for a very small number of sources (n = −10) full-text articles could not be obtained (despite contacting the authors). An equally small (n = 9) number of non-English papers could not be assessed. As is true for most reviews, available sources did not include literature from the global south and disproportionately captured North American and European perspectives. In a similar way, the identification of relevant sources was predominately digital, with limited opportunities to hand-search sources, which may not be entered into online databases and cannot be found via online search engines.

Implication for research and practice

The scoping review demonstrates that the policy climate significantly influences opioid prescribing for older adults (Siciliano, Reference Siciliano2006; Cook, Reference Cook2016). However, many of the studies were set in the US healthcare market and are unlikely to explain current GP opioid prescribing patterns for older adults in the UK. In addition to this, there was a notable lack of literature exploring the trajectories of opioid prescribing after initiation. Most studies explored the initial decision to prescribe but did not look at when, how, and why opioid prescribing becomes routine (i.e., a repeat prescription), dosages increase/decrease, and prescriptions are discontinued or changed for another type of opioid. There was also a gap in how prescribing decisions were perceived by older people and their carers (Closs et al., Reference Closs, Barr and Briggs2004; Boerlage et al., Reference Boerlage, van Dijk, Stronks, de Wit and van der Rijt2008; Green et al., Reference Green, Bedson, Blagojevic-Burwell, Jordan and van der Windt2013) in particular their views on long-term use of opioids.

The UK-specific research needs to consider current prescribing policies and explore the prescriber and patient perspective. Additionally, the impact of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs around opioids, pain, and older people (held both by clinicians and by patients/carers) should be explored within the context of multi-morbidity and treatment burden. While there are few attitudinal studies to date and none are based in the UK, these studies suggest that ageism, in particular, may play a significant role (Kaasalainen et al, Reference Kaasalainen, Coker, Dolovich, Papaioannou, Hadjistavropoulos, Emili and Ploeg2007; Niemi-Murola et al., Reference Niemi-Murola, Nieminen, Kalso and Pöyhiä2007). Research adopting a qualitative approach is needed to capture the complexity of interactions between patient, clinician, and system factors and this learning should be used to inform GP training and practice development.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Funding

A small grant was provided by the Royal College of General Practitioners South East Thames Faculty.