Group psychotherapy is one of the most widely practised treatment methods in psychiatry, with an extensive literature, but it has long been regarded as the poor relation to individual therapy. Nineteenth-century ideas about the primacy of the individual, taken up by psychoanalysis, continue to dominate Western culture. Mrs Thatcher's famous remark “I don't believe in society. There is no such thing, only individual people, and there are families” (Women's Own, 31 October 1987) typifies the extreme view in which the self and the individual's needs are paramount and are set above those of the group. Foulkes in the 1950s had put forward the opposite position, arguing that there is no such thing as an individual that exists apart from and outside the social (Reference FoulkesFoulkes, 1948; Reference Foulkes and AnthonyFoulkes & Anthony, 1957).

Most recent psychotherapy theorising has moved away from the drive-based view of the individual to a more intersubjective, relationship-based model where the quality of early attachments is seen as being of fundamental importance. Dynamic group therapy lends itself to this view and is a rich and productive arena for developing these ideas. The trend of administering in group settings and semi-manualised versions treatments originally described for use with individuals has spurred on dynamic group therapy researchers, who until relatively recently had been slow to develop an evidence base for their therapies. For example, both cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychoeducational cognitive therapy were originally described for individuals and are now increasingly being provided to groups. There are now robust research findings showing the effectiveness of dynamic groups as a powerful intervention for a number of disorders, including depression, personality disorder and anxiety states (Reference Robinson, Berman and NeimeyerRobinson et al, 1990; Reference Budman, Demby and RedondoBudman et al, 1998).

This paper describes the range of group therapies currently practised and reviews the theory, indications and effectiveness of dynamic group therapy.

A group for every patient?

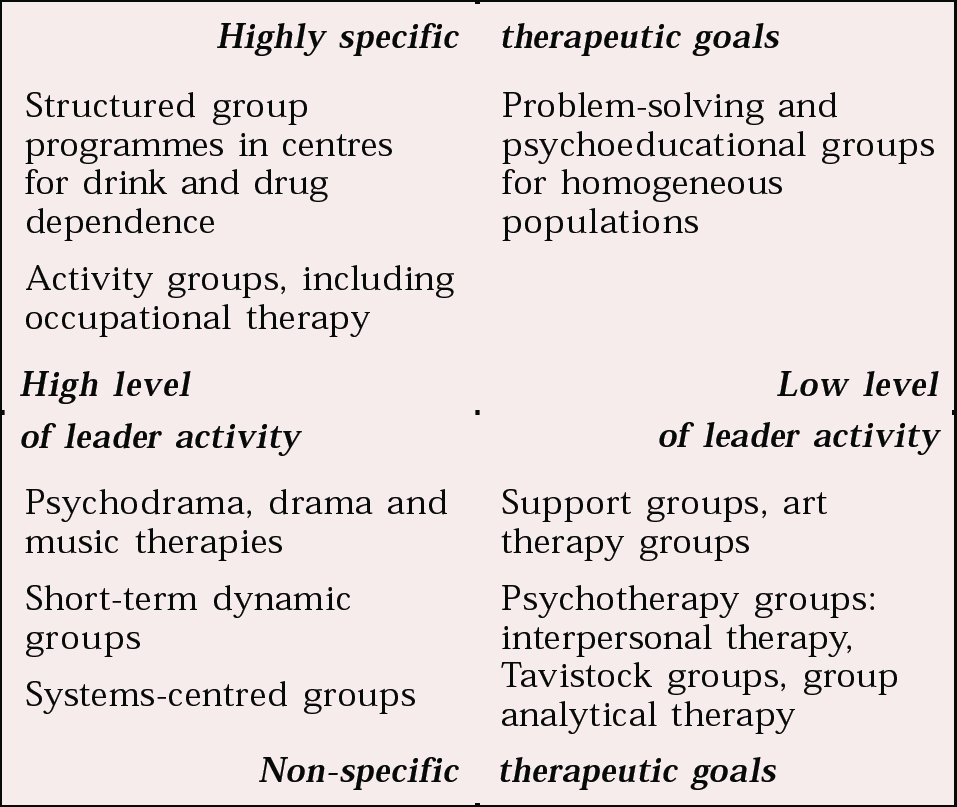

One way of classifying group methods is by looking at two factors: therapeutic goals and group leadership (Pines & Shlapobersky, 2000) (Fig. 1).

Therapeutic goals

Groups that have specific goals, such as overcoming drink or drugs dependency or coming to terms with a diagnosis of cancer, have a homogeneous population with a shared and clearly stated aim. Psychodynamic psychotherapy groups, on the other hand, are made up of patients with a range of different problems and goals that are less easily defined other than in terms of overcoming difficulties and feeling better, which for each patient will hold a different personal meaning.

Leadership

High levels of leader activity such as in psychoeducational or anxiety management groups mean that the group is being directed in its experience in order for members to acquire a new technique or skill. The learning is, in part, through identifying with the leader as an idealised object. In psychodynamic group psychotherapy with less explicit direction from the leader, anxiety among group members increases and hitherto unconscious dynamics become more apparent. Transference and countertransference phenomena abound and can be clarified, with the potential for interpersonal learning. There is a range of leadership styles between these extremes, which allows for more or less personality restructuring.

Basic forms of group

Within the quadrants illustrated in Fig. 1, four basic forms of group emerge: activity groups; support groups; problem-solving and psychoeducational groups; and psychodynamic groups.

Activity groups

Engaging patients in a form of focused activity or work is the oldest form of therapy group and has played an important role in helping to rehabilitate patients from the earliest days of the asylum up to the present. Therapy groups defined by an activity play an important role in in-patient units: groups using cooking, exercise, craft or art work can help to develop social skills and address hidden anxieties and also foster a sense of communality. Such groups also provide a useful function in enabling monitoring of individual patients' response to treatment or readiness for discharge. Staff engaged in such groups, often occupational therapists, nurses or art therapists, need basic training in and an understanding of group dynamics, as often these groups are made up of the most vulnerable and disturbed patients.

Support groups

Although activity groups require a high level of leader activity and have specific therapeutic aims, the opposite is true of support groups. They provide a psychosocial network and offer opportunities for problem-sharing, usually for patients with chronic mental and physical illness for whom a more exploratory dynamic form of therapy would not be indicated. The aim is to maintain homoeostasis: change is not expected and any that occurs is gradual. The regularity and boundaries of the group, although not as stringent or prominently adhered to as in psychodynamic groups, nevertheless provide an essential containing function.

Support groups for staff operate using the same principles and are often essential in promoting the healthy running of an institution. A well-functioning staff-support group will help its members manage more effectively, for instance, the often unacknowledged anxiety generated by working with disturbed patients.

Problem-solving and psychoeducational groups

The range of groups that fall under this heading are similar to support groups, in that they provide opportunities for interpersonal learning and ego support. Unlike support groups, they tend to be made up of individuals with similar problems working towards clearly defined aims. Alcoholics Anonymous, Alanon, Gamblers Anonymous, anger management groups and cognitive–behavioural groups for patients with defined diagnoses (e.g. depression or eating disorders) are examples of this category of group. The emphasis is on shared learning, with some modelling of the group leader; unconscious dynamics are not explored and the group itself is not viewed as a therapeutic force for change.

Psychodynamic groups

The aim of psychodynamic group therapy, in all its different forms, is lasting personality change brought about through non-directive free association. The particular way the therapist behaves in the group will differ depending on the school in which he or she is trained, but by and large the therapist will not ‘lead’ the group in an obvious way. Initially, this will generate a certain degree of anxiety until the group establishes its (usually unspoken) rules. The stance of the therapist allows unconscious dynamics between group members to be examined and personality change to be achieved in the working through of new understandings within the transference and countertransference material.

Psychodynamic groups tend to be heterogeneous in their make-up, which benefits patients with diffuse personality problems and interpersonal difficulties that have resulted in chronic states of anxiety and \ or depression. Exclusion criteria for this form of therapy are shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Exclusion criteria for dynamic group psychotherapy (Reference Dies, Allonso and SwillerDies, 1993)

Patients in acute crisis

A history of broken attendance in therapy

Major problems of self-disclosure

Difficulties with intimacy generalised into personal distrust

Defences that use denial excessively

Impulsive behaviour patterns

Patients who refuse

Models of psychodynamic group psychotherapy

Three main traditions of psychodynamic group psychotherapy are practised in the UK: interpersonal, Tavistock and group analytical. They share much common ground but are also marked by differences in leadership style and underlying theoretical assumptions.

Interpersonal group therapy

Interpersonal group therapy aims to provide a corrective emotional experience, in which group members are collectively encouraged to allow their adult thoughts and feelings to modify their earlier traumatic experiences. The emphasis is on interpersonal learning, with the group leader's participation tending to minimise the impact of transference tensions. The group leader encourages connections to be made from the past to the ‘here and now’ and between behaviours occurring outside and within the group. There is greater therapist transparency than in the other approaches and interpretations play a lesser role. Yalom (1970) was influential in developing this model. His research identified the now well-known 12 curative factors from a series of therapy variables correlated with patient outcome (Box 2).

Box 2. Yalom's curative factors (Reference YalomYalom, 1970)

-

1 Interpersonal learning

-

2 Catharsis

-

3 Group cohesiveness

-

4 Self-understanding

-

5 Development of socialising techniques

-

6 Existential factors

-

7 Universality

-

8 Instillation of hope

-

9 Altruism

-

10 Corrective family re-enactment

-

11 Guidance

-

12 Identification/imitative behaviour

The Tavistock model

The Tavistock model was developed by Bion (1961) after the Second World War and it has proved to be a deceptively simple but important way of understanding what happens in groups, with a wide range of application. He observed that every group operates at two levels: the “work group” and the “basic assumption group”. Group members may strive towards completing the task of the group in a rational and orderly fashion but find themselves constantly undermined by what Bion termed basic assumptions. He saw these as primitive defensive responses to the anxiety generated by the experience of being in a group. They impede the group's capacity for rational work and lead groups to behave in an ‘as if’ manner. In other words, group members find themselves feeling and behaving as if there were an accepted assumption that was implicitly understood and shared by all. He described three basic assumptions: dependency; fight or flight; and pairing. They affect the whole group, with one basic assumption operative at any one time. He postulated that basic assumptions were clusters of defences against psychotic anxieties present in all groups. Each member participates according to his or her “valency” for each basic assumption. Elucidation of these unconscious group processes provides group members with opportunities for profound self-understanding.

Dependency

The dependency basic assumption is a defence against depressive anxieties and is operative when group members behave as if only someone else, usually the group analyst, had the power, ability and knowledge to satisfy their needs. Group members experience themselves as weak, ineffectual and incapable of helping each other. Gabbard (1994: p. 126) describes this situation thus:

“ The underlying fear is that their greed will engulf the therapist and result in their being abandoned. To defend against the anxiety and guilt connected with their potential destruction of the therapist (i.e., their mother at an unconscious level), the patients believe that the therapist is an inexhaustible, omniscient and omnipotent figure who will always be there for them and who will always have the answers.”

Fight or flight

In the fight or flight basic assumption, group members behave as if there were some external threat, the response to which can result only in a fight or flight. Paranoid fantasies abound and the group becomes a fearful and non-reflective place, with action being thought of as the only solution. The group can feel united against the perceived threat and does all it can to maintain the ‘badness’ as external. In this basic assumption, the group can be understood as having regressed to the paranoid–schizoid position formulated by Klein.

Pairing

The pairing basic assumption can be seen to operate when two members pair up and become involved in long and intense discussions; other group members behave in a way that facilitates the exchange and make no attempt to discuss their own problems. A pervasive atmosphere of optimism and hopefulness develops, along with a buoyant attitude that almost anything is possible. This may be viewed as a form of collective manic defence against the group's anxieties about its own destructiveness; the unspoken and usually unconscious belief is that the two people involved will create something beautiful and enduring that will passively transform the other members.

The analyst's funtion

The task of the analyst within the Tavistock model is to interpret group phenomena. Interpretations are made about and to the whole group, on the basis of the analyst's understanding of projections from the group as a whole. This leads to a style of leadership that is quite distinct from either the interpersonal or the group analytical approach. The analyst places herself or himself outside the group, remains opaque and refrains from relating to individual members, as this is thought to support the basic assumption mode current in the group.

Group analysis

The third tradition of psychodynamic group therapy is group analysis, which was developed by S.H. Foulkes (1948) and is now the principal form of dynamic group therapy offered within the National Health Service (NHS) (Box 3). Before looking at the method of group analysis I will outline some key areas of theory. For further information, see Roberts & Pines' (1992) review article on the background, theory and practice of group analysis and Dalal's (1998) in-depth critique of Foulkes's thinking.

Box 3. Practicalities of dynamic group psychotherapy

Group sessions usually last 1½ hours and run weekly or twice weekly

Patients being treated in a ‘slow open’ group would remain in therapy on average for between 18 months and 3 years (longer for severe, chronic mental illness and personality disorder)

The conductor's central tasks are to establish and maintain group boundaries and to foster an atmosphere of free and open communication, offering comments/interpretations to individuals and to the group as a whole

During the early weeks of treatment, patients often report a worsening of symptoms, and the risk of premature termination is highest

Location

Foulkes described the individual's disturbance as an incompatibility between the individual and his or her original group, i.e. family. He believed that the infant introjects relationships and patterns of relationships such that “the so-called inner processes in the individual are internalisations of the forces operating in the group to which he belongs” (Reference Foulkes, Foulkes and PinesFoulkes, 1990: p. 212). By this he means that “so-called inner processes” are not inner processes at all but are internalised group dynamics. He drew an analogy between the group and a jigsaw puzzle, where an individual is like a single piece of the jigsaw, without much meaning on its own. On joining a therapy group the individual tries to reconstruct the original jigsaw of his family, shaping the other people to fit.

Communication

In a radical rewriting of Freud's instinct theory, Foulkes suggested that it is the impulse to communicate, rather than the discharge of instincts, that is primary to the development of the mind. Thus, the process of communication itself is seen as the operational basis of all therapy in the group. Foulkes stated it thus: “Mental sickness has a disturbance of integration within the community at its very roots – a disturbance of communication.” (Reference Foulkes and AnthonyFoulkes & Anthony, 1957: p. 24)

The matrix

Foulkes conceived of the group as developing a matrix, a complex unconscious network of interactions between individuals, subgroups and the whole group. At one level, this can be understood as the shared ground of the group, in which every event that takes place within the group's boundary is meaningful as a communication. At another level, the matrix has a more elusive and less definable function of receiving, containing and transforming each individual's contributions in a manner that is both integrating and ultimately healing. Interesting links have also been made with attachment theory, in which the profound sense of belonging inherent to the concept of the matrix is linked to that of the ‘secure base’.

The conductor

Lao Tze, many centuries ago, wrote “The greatest leader is he who seems to follow.” The group leader in group analysis is known as the conductor and maintains an attitude of non-intrusive interest in both the individuals and the group as a whole. He or she takes responsibility for pointing out unacknowledged sources of conflict and encouraging the establishment of free-floating discussion. The conductor is active in supporting the integration of the group and will balance interpretations to individuals and to the group as a whole with supportive, reflective comments. Transference relationships are explored as they evolve and the phenomena of projective identification and mirroring are untangled in a way that allows for greater personal awareness and acceptance. The holding or containing function of the group conductor is at least as important as any interpretations given. The conductor is discriminating in any help given: Foulkes (1948) wrote that this help is “like a loan, wisely administered, helping recovery, but stimulating activity and self help on the part of the receiver, not delaying it or making him even more dependent”.

How does group therapy work?

Various factors are responsible for creating the changes in patients who have been treated in group therapy. Foulkes believed that there are four main therapeutic processes: mirroring, exchange, social integration and activation of the collective unconscious. The first three correspond to Yalom's curative factors; the fourth is more difficult to define but it corresponds to Foulkes's notion of the group matrix.

Foulkes coined the phrase ‘ego training in action’ to emphasise the learning aspect inherent in group analysis; insight (understanding of the self) he related to ‘outsight’ – the understanding of others. He believed that an essential aspect of therapeutic change lies in people discovering what they can do for others. Garland (1982) has examined the therapeutic process from a systems theory perspective. She argues that for each individual the change-creating process is synonymous with becoming a member of an alternative system – the group:

“It is precisely through attending to the non-problem that the individual becomes a member of an alternative system to the one in which his symptom, as an expression of its pathology, was generated and maintained – and this process alone, this becoming part of the group (as opposed to attending it), is sufficient to effect change” Garland (1982: p. 6).

In this view, the group conductor's task is to create and sustain a setting in which the substitution of the ‘non-problem’ for the ‘problem’ may occur.

Foulkes contrasted the ‘vertical’ analysis of individual therapy, in which there is a focusing on the roots of the problem, with the ‘horizontal’ analysis of group therapy, in which the emphasis is on developing an ever wider and deeper form of communication in the here and now of each group session. Garland offers a gardening analogy: a gardener faced with flower-bed abandoned to weeds may either attempt to pull up the root system of all the weeds or she may plant ground cover between the plants she wants to preserve and encourage its new and healthy growth to take over the territory occupied by the weeds. As the individual becomes incorporated into the secondary system (the group) the individual's problem is, of course, still there but it is dealt with increasingly at the level of metaphor and is available to be played with in the Winnicottian sense.

Tschuschke & Dies (1994) have made an in-depth study of five therapeutic factors: group cohesiveness, self-disclosure, feedback, interpersonal learning and family re-enactment. They found that that group cohesion showed a linear positive relationship with outcome in almost all published reports of group therapy efficacy. It has been suggested that it acts as a precondition for therapeutic change, providing a strong alternative system (the healthy ground cover of the gardening analogy). They suggest that affective integration into the group promotes a capacity for self-disclosure, which in turn leads to more frequent interpersonal feedback. The earlier this feedback loop is established, the more likely it is that there will be a positive outcome for that individual. This suggests that interpersonal feedback needs time to be fully integrated before it is helpful. Their study highlights the important point that different change-inducing mechanisms become important at different phases during the group's evolution.

Is group therapy effective ?

The beneficial effects that a therapy group can have on an individual have long been recognised by group workers but without the support of rigorous scientific scrutiny. Comprehensive reviews by Dies (1993), Piper (1993) and Fuhriman & Burlingame (1994) have begun to address this imbalance. Until recently there was a dearth of high-quality studies comparing the effectiveness of individual and group therapy for patients with similar characteristics. Within the past 10 years or so a number of studies using meta-analysis have shown equal effectiveness for the two treatment modalities in the treatment of both depression and personality disorder (Reference Robinson, Berman and NeimeyerRobinson et al, 1990; Reference TyllitskiTyllitski, 1990; Reference Budman, Demby and RedondoBudman et al, 1998). Toseland & Siporin (1986) reviewed 74 studies that compared individual and group treatment, 32 of which met their criteria for inclusion. Group treatment was found to be as effective as individual treatment in 75% of these studies and more effective in the remaining 25%. In no case was individual treatment found to be more effective than group treatment. Group treatment was more cost-effective than individual therapy in 31% of the studies. McDermut et al (2001) provide the latest meta-analytic review of the effectiveness of group psychotherapy in the treatment of depression (for a review of their paper, see Reference TruaxTruax, 2001). Of the 48 studies examined, 43 showed statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms following group psychotherapy; nine showed no difference in effectiveness between group and individual therapy; and eight showed CBT to be more effective than psychodynamic group therapy (Box 4).

Box 4. Effectiveness of dynamic group psychotherapy

Reviews using meta-analysis show group therapy to be as effective as individual psychotherapy for the treatment of depression and personality disorder

Patient selection – getting the right mix of patients, taking into account the presenting problem, the patient's personality and predominant defence style – is a vital aspect of a successful outcome

Group cohesion shows a linear positive relationship with outcome and is thought to act as a precondition for therapeutic change

As an adjunct to the treatment of schizophrenia, group therapy has been used successfully for the past 70 years and has been shown to be effective in reducing social isolation and increasing the use of adaptive strategies. Kansas (1986) reviewed 43 controlled studies of the use of group therapy in schizophrenia and concluded that it has a positive effect on a range of outcome measures. Interpretations that reveal or explore unconscious conflicts have been shown to be generally unhelpful, but an emphasis on feedback and support increases an atmosphere of connectedness and cohesion within the group, which aids interpersonal learning (Reference KapurKapur, 1993). Group therapy is, however, rarely made available for this patient group, owing to the increasing trend to focus on the ‘management’ of patients with long-term mental illness rather than on therapy, a trend fuelled by an unfounded belief that therapy is likely to do more harm than good.

Group therapy has also been shown to be effective in other patient populations. Homogeneous groups for patients with chronic physical illness are successful in treating symptoms of anxiety and depression and improving quality of life. Particular interest has centred on patients with cancer, and some researchers have found a significant improvement in survival rates following group therapy intervention. It is postulated that this operates through an enhancement of immune functioning (Spiegal et al, 1981).

Although most patients referred for psychotherapy are suitable for group therapy, the most important aspect of a successful outcome is selecting the right patients for the group, i.e. getting the right mix of problems, personalities and habitual defence style. Much of the literature on patient selection has focused on its role in building cohesion. Careful patient-screening also serves to minimise the drop-out rate resulting from patient–group mismatches (Reference Roback and SmithRoback & Smith, 1987). Further research is needed to refine our understanding of which patients are at risk of prematurely terminating treatment and to establish the optimum duration of treatment for different patient groups.

The ubiquity of group processes

Group therapy harnesses the dynamics that occur between individuals and, within a clearly defined boundary, steers them towards a therapeutic outcome (Box 3). Within any defined system (e.g. the institutions within which we work) people have a relatedness to each other, whether they like it or not. Dynamics in institutions caring for people with mental illnesses have the potential for dysfunction owing to the high levels of anxiety (often unacknowledged) generated from working alongside disturbed patients. These anxieties are exacerbated by increasing bureaucratisation, pressure for beds, lack of resources, etc. Institutional as well as individual defences operate against such potentially overwhelming anxiety: institutional denial, displacement, projection and so on are common. The end result very often is that communication breaks down between and within teams. Therefore staff also need to meet in groups to reflect on their experiences and for anxieties to be contained and modified into a more manageable form. The fall-out for the individual that can result from the institutional mismanagement of such dynamic processes can be significant, leading to profound personal unhappiness and burn-out.

Jacques (1955) and Menzies-Lyth (1959) described the social defences of organisations: the different strategies by which mental pain is kept at a distance through the use of complex bureaucratic structures and protocols. These not only give the false impression of orderliness and the illusion of immunity from psychic contagion but also become the substitute for the mental work of the organisation itself – the work of containing anxieties, the realistic appraisal of the limitations of the system, the acceptance sometimes of failure. As has been noted (Reference Holmes, Barnes, Ernst and HydeHolmes, 1999), there is a paradox at the centre of what constitutes the real ‘emotional work’ of the group: the more the group is able to face its weakness, the stronger it becomes; the less it is able to admit to fears and failures, the more likely failure is to occur. Staff-support groups in in-patient units or in community teams have a vital role to play in identifying disturbances and aiding communication within the system without resorting to defensive practices.

The difficulty that staff-support groups have in establishing themselves on psychiatric wards and the fear and hostility with which they are sometimes met reflect the current crisis of therapeutic ambivalence that is widely prevalent on in-patient units. There is widespread evidence that general psychiatric wards have lost their therapeutic focus; in-patient group psychotherapy has become the provenance of specialist units and milieu therapy has been taken over by therapeutic communities (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1998). The therapeutic vacuum that has developed in a large proportion of in-patient units needs urgent attention and can best be filled by rediscovering and harnessing the therapeutic potential of both staff and patient groups.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. In psychodynamic therapy groups:

-

a the leader often makes practical suggestions

-

b the leader encourages the emergence of unconscious dynamics

-

c patients are told to say only things that make sense

-

d most patients respond after about six sessions

-

e beneficial personality change is achievable even for disturbed patients.

-

-

2. Group analytical psychotherapy:

-

a is the principal form of dynamic group therapy offered within the NHS

-

b was developed by S.H. Foulkes

-

c views the individual as having internalised his or her community of origin

-

d aims for an ever-deepening form of communication

-

e is suitable only for well-integrated patients with minor problems.

-

-

3. Group psychotherapy research:

-

a shows that group treatment is as effective as individual treatment

-

b shows that good outcome is strongly correlated with group cohesion

-

c shows that patient selection minimises dropout resulting from patient–group mismatches

-

d suggests that the presence of personality disorder is a contraindication to treatment

-

e shows that group treatment is not effective in physically ill patients.

-

-

4. The Tavistock model of group therapy:

-

a was developed by Carl Rogers

-

b is a form of supportive therapy best suited to anxious patients

-

c views the emergence and working through of basic assumption states as an important group task

-

d has a distinct style of leadership that makes interpretations only to the whole group

-

e can be learnt as a 12-week manualised correspondence course from the Tavistock Clinic.

-

-

5. Yalom's curative factors in group therapy:

-

a have been largely revised and are now regarded as out-dated

-

b include the basic assumption state of pairing

-

c do not apply to analytical groups

-

d include the instillation of hope and universality

-

e were derived from a series of therapy variables correlated with patient outcome.¤

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | T | b | T | b | T | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | F | d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T |

Fig. 1 A classification of group methods

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.