Zwara Berber is a variety of Nafusi (ISO 639-3; Lewis, Simons & Fennig Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2016) which belongs to the eastern Zenati group within northern Berber (where Berber is the scientific term for Tamazight), a branch of Afro-Asiatic. Zwara (Zuwārah, Zuwara, Zuāra, Zuara, Zouara) is a coastal city located at 32.9° N, 12.1° E in Libya. The speakers refer to themselves as /at ˈwil.lul/ (also /ajt ˈwil.lul/) ‘those of Willul’ and to their specific variety of the language as /t.ˈwil.lult/ ‘the language of Willul’.Footnote 1 Having no official status during the Italian colonization of Libya and the first period after the country's independence in 1951, repression of the language became severe after the Cultural Revolution of 1973. Its propagation through teaching and the media fell under a constitutional ban on the denial of the Arab identity of the state, and qualified as such as treason, a capital offense. Until the revolution of 2011 (‘17 February’), the language was therefore not spoken in cultural, educational or governmental domains and could not be taught, printed or broadcast. The number of Tamazight speakers in Libya is estimated at 184,000 in Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2016) and at 560,000 by Chakel & Ferkal (Reference Chaker and Ferkal2012). In the absence of a municipal register, the number of inhabitants in Zwara is uncertain. A conservative estimate is between 50,000 and 100,000, which is also the number of speakers of the Zwara variety. Other than through exposure by radio and television, children learn Arabic only from age six, when attending school. Speakers have variable L2 Arabic competence depending on exposure to the language.

Until the effective suspension of the national parliament in October 2014, attempts were under way to award an official status to Amazigh language and culture in a new constitution, on a par with Arabic and two Nilo-Saharan languages spoken by the Toubou in the southern border area, together known as Tebu. Teachers are being trained in the use of Tifinagh (the Tamazight alphabet) in preparation for the inclusion of Tamazight in the school curriculum. These aspirations have remained in force after the deterioration of the political climate since early 2015.

Earlier work on Zwara Tamazight dealt with the morphology of pronouns and nouns (Mitchell Reference Mitchell1953), which was responded to by Hamp (Reference Hamp1959), and verbs (Mitchell Reference Mitchell1957a). The latter was superseded by a posthumous publication of conversational texts, earlier inspected and reported on by Galand (Reference Galand and Di Tolla2005), together with an extensive treatment of the verbal morphology and a preface by the editors, Harry Stroomer and Stanly Oomen (Mitchell Reference Mitchell, Stroomer and Oomen2009). In addition, there is a list of fish names (Serra Reference Serra1970) and anthropological work (e.g. Serra Reference Serra1971). The only phonetic work is the second section in Mitchell (Reference Mitchell and Firth1957b); it deals with gemination and is referred to below in section ‘Consonants’.

Consonants

There are 31 consonants in Zwara Berber, including nine contrastively pharyngealized consonants and excluding geminates. The Consonant Table corresponds to the list in the editorial preface to Mitchell (Reference Mitchell, Stroomer and Oomen2009: x) with the exception of /nˁ ʁˁ/, which are not listed there, and /ʔ/, which is.

Glottal stops do not occur other than as an optional paralinguistic feature closing off utterance-final stressed syllables, as an expression of emphasis (see section ‘Intonation’), and predictably before a word-initial vowel after pause, as in /ˈ[Ɂ]adˁ.ʁaʁ/ ‘stone’. The pharyngealized uvular /ʁˁ/ is probably innovative. Four out of eight consultants used /ʁ/ instead of /ʁˁ/ in the word for ‘churned milk’, an everyday word, i.e. /ˈa.ʁi/. By default, the forms given below are as for the variety without /ʁˁ/. Finally, /ħ ʕ/ are arguably marginal segments, since they occur in words that are originally Arabic.

Voicing in obstruents

The plosives /b d dˁ g/ are voiced throughout their closure phase, also finally and initially, while syllable-initial voiceless /t tˁ k q/ have VOTs ranging from +50 ms after /q/ to +10 ms after /t/. The fricatives /z zˁ ʒ ʁ ʁˁ ɦ/ are fully voiced, also in final position, while /f s sˁ ʃ χ ħ/ are voiceless in all positions. /ʕ/ is a pharyngeal vocoid. The laryngeal constriction creating ‘pharyngealized voice’ may lead to low f0, particularly in the onset, as in /ˈʕə.li/ ‘Ali’ and /i.ˈʕj.jədˁ/ ‘He is weeping’ (Esling Reference Esling2005). Figure 1 shows a pronunciation of the second word in which f0 drops from low pitched [i] as a result of the constriction before rising again in the vocoid beginning the rime. (For the transcription of schwa, see section ‘Vowels’.) There is also weak pharyngeal friction during the f0 dip. By comparison, /i.ˈmir/ ‘open (adj)’ has no such dip during /m/ (panel (b)).

Figure 1 Low f0 for /ʕ/ in /iˈʕj.jədˁ/ ‘he is weeping’ (left panel) and frictionless modal voice during /m/ in /iˈmir/ ‘open (adj)’ (right panel). Male speaker AA.

Place and manner

The contacts for /t tˁ d dˁ n nˁ l lˁ/ are denti-alveolar. /s sˁ z zˁ/ have an ungrooved, distributed tongue blade articulation on the alveolar ridge, creating low intensity friction. Alveolar /r rˁ/ are tapped in the onset and briefly trilled in the coda, while geminate occurrences are long trills, as in /ˈrˁ.rˁuzˁ/ ‘rice’. The voiced uvular fricative /ʁ/ may be a trill, as in /ˈim.ʁar/ ‘growing up’.

Pharyngealization

Pharyngealized consonants are notated /Cˁ/, following the IPA recommendation rather than the usual practice in Tamazight studies to indicate pharyngealization by a subscript dot. They have a retracted tongue root, along with a raised hyoid, as reported for /zˁ/ in a Moroccan variety by Louali-Raynal (Reference Louali-Raynal2001). Plain consonants have a more forward tongue body, along with a more raised tongue front, with considerable acoustic effects on adjacent vowel articulations (see section ‘Vowels’). The Zwara variety lacks the contrastively pharyngealized palato-alveolar fricatives of Imdlawn Tashlhyit (Dell & Elmedlaoui Reference Dell and Eldmedlaoui2002: 13; Ridouane Reference Ridouane2014) but, unlike Tashlhiyt, it does have a pharyngealized bilabial nasal, in addition to the marginal pharyngealized voiced uvular fricative. Strikingly, plain consonants with pharyngealized counterparts are among the more frequent consonants (see Figure 2). With the exception of /zˁ/, which approaches the frequency of /z/, pharyngealized consonants are considerably less frequent than their plain counterparts.

Figure 2 Frequency of occurrence of plain (black) and pharyngealized (grey) consonants in a 420-word corpus.

While pharyngealized consonants tend to co-occur in words, there is no absolute constraint that words must be exhaustively pharyngealized. Examples of words with contrastively pharyngeal consonants throughout are /ˈamˀ.mˀasˀ/ ‘centre’, /lˁ.ˈmˁnˁ.dˁarˁ/ ‘cushion’ and /tˁa.ˈzˁu.dˁa/ ‘plate’. There are of course many words that are fully pharyngeal phonetically but contain non-contrastively plain consonants, such as /mˀ.ˈmˀχ.χərˀ/ ‘late’, /ˈlˁb.sˁatˁ/ ‘carpet’, /ba.ˈtˀa.tˀa/ ‘potato’ and /a.ˈmˀtˀ.ʃi/ ‘fig from second harvest’. In /ħa.ˈrˀb.mət/ ‘incite to war’ and /t.ˈzˁi.wa/ ‘big plate’ contrastively plain and pharyngealized syllables are adjacent. There is no requirement for pharyngealization to spread through a geminate. In /jt.ˈtˁnˁ.nˁədˁ/ ‘it is rolling’, the shift occurs during the [t]-closure. Pharyngealization is syllable-based, except that for many speakers, pharyngealization may be unequal in word-final coda clusters ending in the feminine suffix /t/, as in /ta.ˈmz.zˁuʁt/ ‘ear’, also /ta.ˈmz.zˁuʁtˁ/ (from /a.ˈmz.zˁuʁ/ ‘big ear’). The difference between the two versions is audible in the burst occurring at the release. In initial geminate [tː], as in /t.ˈtˁa.sˁətˁ/ ‘cup’, this shift in pharyngealization may only be detectable in a preceding word ending in a vowel or a sonorant consonant. The word /a.ˈmz.zˁuʁ/ ‘big ear’ is additionally a rare example of a shift in pharyngealization in a word-medial geminate.

Contrastive pharyngealization on consonants is to be distinguished from phonetic pharyngealization, present during vowels and during consonants which do not contrast for pharyngealization, inside or adjacent to pharyngealized syllables. Vowels near pharyngealized consonants are retracted and somewhat lowered relative to their plain allophones (for details see section ‘Vowels’), as illustrated by /l.ˈbi.ru/ ‘pen’ – /lˁ.ˈbi.tˁərˁ/ ‘first harvest fig’, /ˈari/ ‘write:imp:sg; open:imp:sg’, /ˈarˁu/ ‘give birth’, /ˈan.ja/ ‘rhythm’ – /ʒr.ˈmˁanˁ.ja/ ‘Germany’ and /ˈaʒ.did/ ‘new’ – /ˈaʒ.dˁidˁ/ ‘sea gull’. The effect may spill over into adjacent syllables, as in the vowel of the first syllable of ‘sea gull’: [äʒdˁɘdˁ]. Similarly, non-contrastively plain consonants will be phonetically pharyngealized in pharyngeal surroundings, as in the case of /b/ in /gd.ˈrˁab.lˁəsˁ/ ‘in Tripoli’. The consonants /q χ/ combine with tautosyllabic pharyngealized as well as plain consonants, as in /ˈə.quzˁzˁ/ ‘anus’ (compare /a.ˈbq.quʃ/ ‘Abeqqush (surname)’ and /i.ˈχudˁdˁ/ ‘he shook’ (compare /χ.ˈχul/ ‘now’). In the case of the voiced uvular fricative, we cannot be sure whether pharyngealization is allophonic or phonemic without knowing whether the speaker contrasts /ʁˁ/ and /ʁ/, as in the case of /ˈtˁalˁ.ʁ(ˁ)əmˁt/ ‘female camel’.

Geminates

Geminates occur initially, medially and finally in the word, as shown by /sˁ.ˈsˁə.qər/ ‘hawk’, /a.ˈʕw.wəl/ ‘housework’ and /i.ˈqudˁdˁ/ ‘be capable of it:imp:sg’. Based on palatographic data for one speaker, Mitchell (Reference Mitchell and Firth1957b) shows that in all three positions, the area of contact of denti-alveolar articulations for [tː sː nː] is wider than for their singleton counterparts, extending further onto the front teeth, while for [tː] the greater contact area applies to the entire semi-circular gum line of the upper jaw. A similar difference in contact area for alveolar plosives was reported for Tashlhiyt by Ridouane (Reference Ridouane2007) on the basis of electropalatographic data. Mitchell's kymographic data additionally show that the release of a geminate plosive leads to a burst with a considerably higher pressure than in the case of a singleton (his Figure 21). In our data, we find that final singleton plosives are not audibly released or only weakly so, and a firmly audible release may well serve as a cue to gemination. Mitchell's data also show that the vowel before the geminate has a voice lag into the closure stage which is absent in the case of the singleton (his Figure 22). Intervocalically, singletons have only 36% of the duration of geminates, based on the citation pronunciation of nonsense words of the structure /ˈəC(C)a/, as shown in Figure 3 (t = −2.604[28], p < .0001).Footnote 4 The duration difference is larger for sonorants than for obstruents, which take up 28% and 39% of the corresponding geminate durations, respectively. A similarly large duration difference, with intervocalic singletons having 33% of the duration of comparable geminates, was found for four speakers from Morocco on the basis of real words by Louali & Maddieson (Reference Louali and Maddieson1999).

Figure 3 Durations of singleton (black bars) and geminate (grey bars) consonants and flanking /ə/ and /a/, averaged over two pronunciations for all consonants except /ʕ/, whose segmentation was made impossible by its vocoid nature, and /ʁˁ/, whose existence was unknown at the time the speaker was available. N = 58. Speaker BWB.

Assimilations

In some words, /ʁ/ is categorically devoiced before voiceless fricatives, e.g. /ˈiχ.fiw/ ‘my head’ (compare /ˈi.ʁəff/ ‘head’) and /ˈiχ.san/ ‘bones’ (compare /ˈi.ʁəsˁsˁ/ ‘bone’). Final underlying /ʁʃ/ is usually /χʃ/, as in /u.ʁi.ˈsəχʃ/ ‘I don't want’ (compare /ˈχ.səʁ/ ‘I want). Regressive voicing in obstruent sequences is variable, as in /itt.ˈzuf.fu/ ([![]()

![]() z/ddz]) ‘it is wooshing’ from /i.ˈzuff/ ‘it wooshed’. Regressive devoicing is similarly variable. In the recorded story, the initial cluster of /d.ˈtf.fujt/ ‘and the sun’ (first line) is [ttff] in /(l.ˈwa.ri a.ˈbħ.ri) t.ˈtf.fujt/ ‘(the sea wind) and the sun’.

z/ddz]) ‘it is wooshing’ from /i.ˈzuff/ ‘it wooshed’. Regressive devoicing is similarly variable. In the recorded story, the initial cluster of /d.ˈtf.fujt/ ‘and the sun’ (first line) is [ttff] in /(l.ˈwa.ri a.ˈbħ.ri) t.ˈtf.fujt/ ‘(the sea wind) and the sun’.

Vowels

Zwara Tamazight has four vowels, /i u ə a/, which appear in their plain and pharyngealized allophones depending on context.Footnote 5 Separate keywords are given for these allophonic variants:

The plain allophones of /i u/ are front and back high vowels, [u] being between close and close mid, [![]() ]. The plain allophone of /a/ is [ɛ] or [æ], as in /ˈa.man/ [ɛmɛn] ~ [æmæn] ‘water’, or [ä] in syllables with /w/, as in /i.ˈʒn.wan/ [iʒnwän] ‘farm’. Word-finally, /a/ may be central and raised to mid open, as in /ˈnan.na/ [nænnɐ] ‘grandmother’. The plain version of /ə/ varies from close mid centralized front [ë], central [ɘ], [ə] and centralized front [

]. The plain allophone of /a/ is [ɛ] or [æ], as in /ˈa.man/ [ɛmɛn] ~ [æmæn] ‘water’, or [ä] in syllables with /w/, as in /i.ˈʒn.wan/ [iʒnwän] ‘farm’. Word-finally, /a/ may be central and raised to mid open, as in /ˈnan.na/ [nænnɐ] ‘grandmother’. The plain version of /ə/ varies from close mid centralized front [ë], central [ɘ], [ə] and centralized front [![]() ].

].

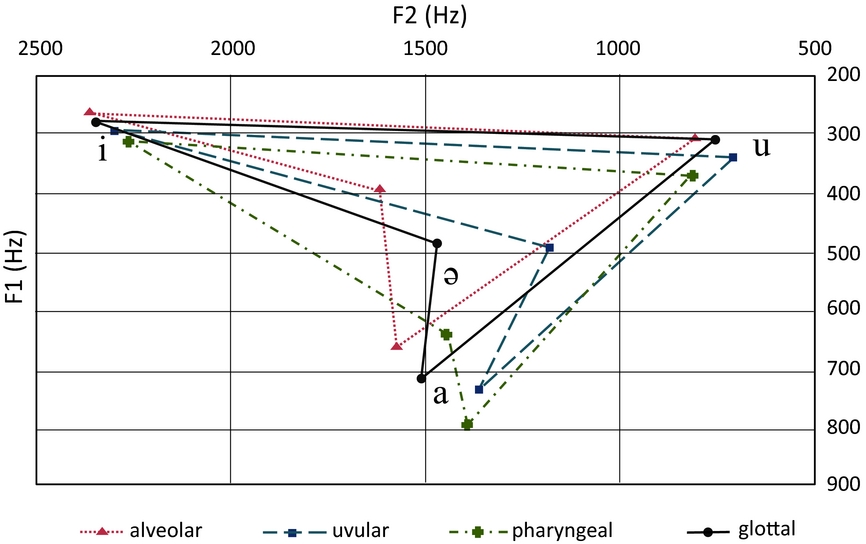

Effects of place of articulation are shown in Figure 4, which gives plots of F1 and F2 measurements for the vowels /i a u/ in plain VCːV nonsense words, for four primary places of articulation, pooled over initial and final occurrences. Because /ə/ does not occur word-finally, its measurements are from word-initial occurrences in both [əCa] and [əCːa], and values were pooled over pre-singleton and pre-geminate occurrences. The solid line connects the formant values for vowels in the glottal context, i.e. before and after /ɦ/, where vowel realizations are unaffected by supralaryngeal articulations. As expected, the plain allophones in an alveolar context are raised and fronted relative to the glottal position, while the plain allophones in the uvular context are retracted and somewhat lowered from the glottal position. The plain allophones in the pharyngeal context are generally lowered, while for /i ə a/ there is also a retraction.

Figure 4 Mean F1-F2 plots of plain allophones of /i ə a u/ in glottal, alveolar, uvular and pharyngeal contexts. N = 2 (glottal), 4 (pharyngeal), 6 (uvular) and 14 (alveolar). Speaker BWB.

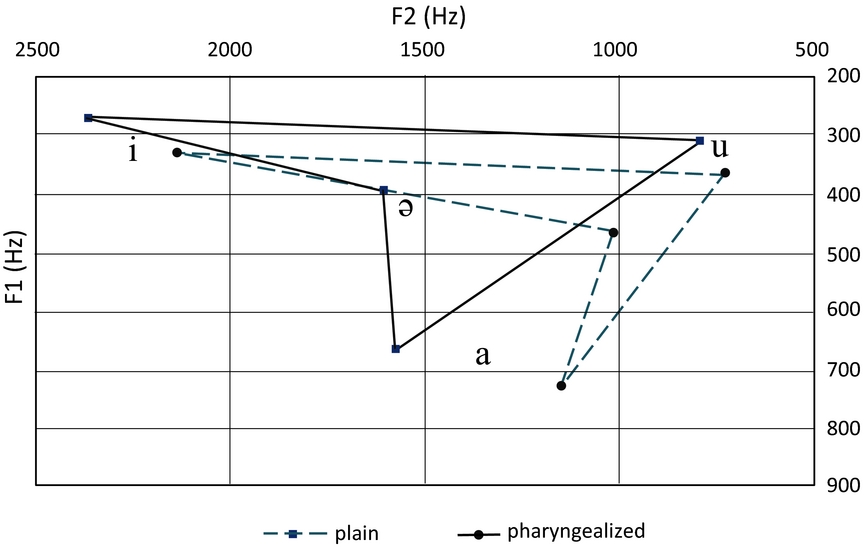

The effect of the pharyngealized consonants on vowel quality relative to plain consonants is shown in Figure 5, which gives the plots of the four vowels as spoken before and after /t d s z m n l r/ and /tˁ dˁ sˁ zˁ mˁ nˁ lˁ rˁ/.

Figure 5 Mean F1-F2 plots of four plain and four pharyngealized allophones of /i ə a u/. N=16. Speaker BWB.

In addition to the greater difference between the allophones of /ə/ than between the allophones of the other vowels, a repeat of the pattern seen in Figure 4, it is noteworthy that the allophonic differences between the plain and pharyngealized contexts are larger than any of the allophonic differences caused by different primary places of articulation. The black bars in Figure 6 show Euclidean distances (Bark) for each of the four vowels between the alveolar and pharyngeal allophones, which are the largest among the allophonic distances between primary places of articulation. The grey bars show the differences between the plain and pharyngealized allophones. The large effect shown in the grey bars underlines the fact that, in the absence of cues to different articulation places, the main perceptual cues of contrastive pharyngealization are invested in the quality of the surrounding vowels. The realistic reproduction of vowel qualities in loans partly relies on the availability of pharyngealized consonants, as illustrated by the treatment of Japanese /o/. Thus, Yoko Ono will have the [o]-allophone only in the second word: /ˈjuku ˈunˁu/ [juku onˁo]. Figure 6 also reveals the large variation for /ə/ noted above, particularly when compared to that of /i u/.

Figure 6 Euclidean distances (Bark) for /i ə a u/ between the alveolar and pharyngeal allophones (black bars) and the plain and pharyngealized allophones (grey bars).

All vowels, including /ə/, appear in stressed as well as unstressed syllables and all may appear in open syllables, but word-finally only /i a u/ are allowed. Examples for /ə/ are /ˈə.dˀarˀrˀ/ ‘foot’, /ˈə.fud/ ‘knee’, /ə.ˈml.mət/ ‘say:imp:f:pl’ and /q.ˈqə.lən/ ‘they accepted’, to be compared with /ˈa.dˀu/ ‘wind’, /ˈuʒ.la/ ‘geographical name’, /ˈu.di/ ‘oil’, which illustrate the occurrence of /a i u/ initially and finally, and with the vowelless syllable in /a.ˈs![]() .ru/ ‘poem’. Since there is no contrast between schwa and the absence of a vowel before a coda consonant, /əC/ and /

.ru/ ‘poem’. Since there is no contrast between schwa and the absence of a vowel before a coda consonant, /əC/ and /![]() / are equivalent in the rime. The extent to which a schwa is phonetically realized when a consonant follows in the same syllable depends to some extent on the nature of that consonant. If this is a sonorant, typically no schwa is realized, as in /a.ˈʃn.jal/ ‘flag’ and /ta.ˈbr.ʃuʃt/ ‘dish cloth’. When it is an obstruent, schwaless pronunciations would appear to be more frequent than pronunciations with schwa, inasmuch as we can tell the difference. Examples are /ʃ.ʃ(ə)k.ˈlˁa.tˁətˁ/ [ʃːklˁɑtˁ

/ are equivalent in the rime. The extent to which a schwa is phonetically realized when a consonant follows in the same syllable depends to some extent on the nature of that consonant. If this is a sonorant, typically no schwa is realized, as in /a.ˈʃn.jal/ ‘flag’ and /ta.ˈbr.ʃuʃt/ ‘dish cloth’. When it is an obstruent, schwaless pronunciations would appear to be more frequent than pronunciations with schwa, inasmuch as we can tell the difference. Examples are /ʃ.ʃ(ə)k.ˈlˁa.tˁətˁ/ [ʃːklˁɑtˁ![]() tˁ], [ʃːəklˁɑtˁ

tˁ], [ʃːəklˁɑtˁ![]() tˁ] ‘chocolate’; /a.ˈdf.fu/, [ædfːu] or [ædəfːu] ‘apple’; and /a.ˈmz.zˁuʁ/ [am(ə)zzˁʊʁ] ‘big ear’. Besides the consonantal context, the position in the word affects this variation. First, word-initially, the presence of /ə/ in onsetless syllables is more likely if the stress is on that syllable, particularly before obstruents, as in /ˈ(ə)k.kəs/ ‘take off:imp:sg’ (compare /χ.ˈχul/ ‘now’, /ˈrˁ.rˁuzˁ/ ‘rice’). Second, schwa is reliably observable in word-final syllables, which are necessarily closed. I have accordingly adopted a convention to transcribe /ə/ in word-final syllables, in open syllables and in stressed word-initial position in phonological transcriptions. Beyond this, there is considerable variation in the duration of schwa, which may be as long as 400 ms, depending on its position in the word and sentence. More discussion is provided in the sections ‘Syllables’ and ‘Intonation’.

tˁ] ‘chocolate’; /a.ˈdf.fu/, [ædfːu] or [ædəfːu] ‘apple’; and /a.ˈmz.zˁuʁ/ [am(ə)zzˁʊʁ] ‘big ear’. Besides the consonantal context, the position in the word affects this variation. First, word-initially, the presence of /ə/ in onsetless syllables is more likely if the stress is on that syllable, particularly before obstruents, as in /ˈ(ə)k.kəs/ ‘take off:imp:sg’ (compare /χ.ˈχul/ ‘now’, /ˈrˁ.rˁuzˁ/ ‘rice’). Second, schwa is reliably observable in word-final syllables, which are necessarily closed. I have accordingly adopted a convention to transcribe /ə/ in word-final syllables, in open syllables and in stressed word-initial position in phonological transcriptions. Beyond this, there is considerable variation in the duration of schwa, which may be as long as 400 ms, depending on its position in the word and sentence. More discussion is provided in the sections ‘Syllables’ and ‘Intonation’.

Syllables

The syllable structure is (C)V(C)(C), where the first C is onset and V(C)(C) the rime, within which V is the nucleus and following Cs the coda. None of the vowels /i u ə a/ can occur in any C-position, but all consonants can occur in the onset as well as in the nucleus (given as ‘V’ in the structural formula, i.e. as syllabic consonants where no schwa is present), and the first coda position. It is typologically rare for /w j/ to contrast with /u i/ in the nucleus. Syllabic approximants occur in /a.ˈɦw.wək/ ‘long walk’ and /i.ˈʕj.jədˁ/ ‘he is weeping’. There are no sequential restrictions, as shown by /a.ˈku.waʃ/ ‘baker’, /ˈij.jis/ ‘horse’, /wuɦ/ ‘this’ and /l.bi.ˈru.wiw/ ‘my pen’, from /l.ˈbi.ru/ ‘pen’ and bound morpheme /-iw/ ‘my’. Words like /ˈil.la/ ‘existence’ and /ˈiχ.rˁadˁ/ ‘comb’ have /i/ in the nucleus, while in /ˈjm.ma/ ‘my mother’ and /ˈjʁ.zˁa/ ‘he dug’ /j/ occurs in the onset. The 3sg:m verbal prefix shows up as /i/ before an onset consonant, as in /i.ˈnˁtˁ.tˁərˁ/ ‘he bounces’, as /j(ə)/ before a syllabic consonant, as in /jq.ˈqar/ ‘he is reading’ and /ˈjəχs/ ‘he wants’, and as /j/ before /i u a/, as in /ji.ˈnig/ ‘he sang’. The fact that attachment of the prefix to /ʁs/ ‘want’ yields /ˈjəχs/ shows that /ʁ/ occurs in the nucleus, not the syllable onset (*/ˈi.ʁəs/), or coda (*/ˈiχs/).

Neither onset nor coda is obligatory, but since word-internal vowel-to-vowel hiatus is disallowed, an onset consonant like /z/ in /ˈi.zi/ ‘fly’ is effectively obligatory. Complex codas occur in two positions in the word. Word-finally, CC is either a geminate, as in /ˈə.ħinn/ ‘be kind:imp:sg’ and /i.ˈlˁutˁtˁ/ ‘he hit with the back of his hand’, or a cluster of consonants. The most frequent second consonant is /t/, as in /ˈta.wərt/ ‘door’ and /ˈtaf.rˀuχt/ ‘girl’; the second word has prefixed and suffixed /t/ (f, compare /ˈaf.rˀuχ/ ‘boy’). Another frequent consonant in this position is /ʃ/, as in /ˈətʃ/ ‘eat:imp:sg’ and /u.ʁi.ˈsəχʃ/ ‘I don't want to’, where it represents a negative suffix. Its voiced counterpart /ʒ/ occurs in /ˈədʒ/ ‘permit:imp:sg’ and /s/ in /ˈjəχs/ ‘he wants’. More varied coda clusters occur in unrestricted positions in loans, like /lˁmˁ/ in /s.ˈtˁuk.ɦulˁmˁ/ ‘Stockholm’, /ms/ in /ams.ˈtr.dam/ ‘Amsterdam’ and /nz/ in /vanz.ˈwl.la/ ‘Venezuela’. By contrast, the Tashlhiyt and Figuig varieties reject word-internal coda clusters. These varieties syllabify the first three segments of ‘Amsterdam’, for instance, as /a.ms/ (see Kossmann Reference Kossmann1997, Ridouane Reference Ridouane2014).Footnote 6

The boundary between the word end and a clitic is not subject to the restriction against hiatus that applies word-internally. The interrogative clitic /a/, which indicates a polar question and attaches to all word forms except imperative verb forms, shows that between words and clitics there is no avoidance of hiatus, as in /tˁa.zˁu.ˈdˁa.a/ ‘A plate?’, from /tˁa.ˈzˁu.dˁa/, where the last two syllables form a long phonetic vowel, i.e. [tˁɑzˁodˁɑː]. It will cause the last consonant of the stem to be the onset of a new syllable, as in /a.bl.ˈbu.la/ ‘An octopus?’ (compare /a.ˈbl.bul/ ‘octopus’). Addition of the clitic will leave the number of syllables in the base unaffected, however, even when segments are resyllabified. For /a.ˈχa.ləd/ ‘sociable’, this gives /a.χa.ˈ![]() .da/, not */a.ˈχal.da/, despite the syllabic well-formedness of that form.

.da/, not */a.ˈχal.da/, despite the syllabic well-formedness of that form.

While geminates occur in all three positions of the word, as observed in section ‘Consonants’ above, their integration in C/V-syllable structure is constrained. There are four different structural positions in which they occur, V.C, VC, C.C and CC. The distribution of these structures over the three positions in the word is exemplified in (1)–(3).

(1)

(2)

(3)

The bipositional sequence C.V is disallowed generally, because of the requirement to create onsets if possible. The only bi-positional sequence of structural elements where geminates might have occurred, but do not, is CV. That is, a geminate consonant never crosses the onset–rime boundary. When the onset consonant is identical to the first consonant in the rime, the onset consonant is released, as in /nən.ˈzas/ ‘we have been sold to him’. By contrast, geminates that straddle a syllable boundary (V.C or C.C) are not broken up, as illustrated by /t.ˈtˀaw.lˀət/ [ttˀɑwlˀət] ‘table’ and /ˈud.dur/ [udːur] ‘dignity’, and the same goes for geminates that are located inside the rime, as in /ˈnˁnˁ.zˁasˁ/ [(ə)nˁːzˁɑsˁ] ‘pear’, where a geminate occurs in the VC rime of the first syllable. These facts about geminates reflect the situation in consonant sequences generally. Those occupying CV may be broken up by schwa, as explained in section ‘Vowels’. Cross-syllabic clusters are never broken up by schwa. A word like /jtt.ˈlˁχ.bəsˁ/ ‘he is deliberately confusing someone’ is [j(ə)ttlˁ(ə)χbəsˁ] (*[-ttəlˁ-],*[-χəb-]).

Prosody

Stress

Unlike Tashlhiyt Tamazight (Grice et al. Reference Grice, Röttger, Ridouane and Fougeron2011, Ridouane Reference Ridouane2014, Röttger, Ridouane & Grice Reference Röttger, Ridouane and Grice2014, Grice, Röttger & Ridouane Reference Grice, Ridouane and Röttger2015), Zwara Tamazight has word stress. Approximately 85% of polysyllabic words have penultimate stress. Remarkably, the presence of /i a u/ in a closed stressed penultimate syllable of a trisyllabic word appears to be characteristic of loan words like /ʒər.ˈmˀanˀ.ja/ ‘Germany’ and /t.ˈmuk.ħəlt/ ‘gun’. Native words overwhelmingly have a syllabic consonant in the stressed penult of trisyllabic words, like /ta.ˈʁ(ˀ)n.ʒajt/ ‘teaspoon’, /ab.ˈlˀq.qu/ ‘pebble’ and /a.ˈkʃ.laf/ ‘mesh of sponge’. This fact is mainly responsible for the typologically uncharacteristic avoidance of high-sonority rimes in stressed syllables. Of the remaining words, 11% have final stress and 4% antepenultimate stress. In the two panels of Figure 7, speech waveforms and f0 tracks of two pronunciations of /a.ˈdf.fu/ ‘apple’ are presented, one with and one without a phonetic schwa between /d/ and /f/ in the second syllable. While the f0 track in the top panel fails to show a peak in the stressed syllable, that in the bottom panel does, during the voiced interval between the onset /d/ and the rime /f/. Native speaker intuition evaluates these pronunciations as the same.

Figure 7 Speech waveforms, spectrograms and f0 tracks of /a.ˈdf.fu/ ‘apple’ by two speakers, one without (top penel, male speaker BWB) and one with a schwa of 67 ms (bottom panel, female speaker FH) in the stressed syllable /df/, on the same time scale with f0 track (Hz).

Final stress regularly occurs in the past verbal form, as in /jb.ˈħər/ ‘he saw’. It may also occur in loan words like /jʁ.ˈlˁidˁ/ ‘it is thick’ (from Arabic) and /l.ban.ˈzint/ ‘petrol’ (also /l.ban.ˈzi.nət/, from Arabic). A representative subminimal pair is presented in Figure 8. Apart from the duration differences, the peak location is considerably earlier in /ˈnq.qəʁ/ [nː![]() qːəʁ] ‘I am killing’ than in /nq.ˈqəl/ [nəqː

qːəʁ] ‘I am killing’ than in /nq.ˈqəl/ [nəqː![]() lː] ‘we agreed’.

lː] ‘we agreed’.

Figure 8 Speech waveforms and f0 tracks of /ˈnq.qəʁ/ ‘I am killing’ (top panel) and /nq.ˈqəl/ ‘we agreed’ (bottom panel), with equal portions of /qq/ attributed to the first and second syllables. Speaker NB.

Antepenultimate stress may occur in words that (potentially) have /ə/ in their final three syllables, as in /tt.ˈɦə.dr.zən/ ‘they are discussing’, /ˈə.ml.mət] ‘say:imp:pl:f’, as well as in loanwords like /l.ˈkaɦ.rə.bət/ ‘car’ and geographical names like /l.ˈqa.ɦi.ra/ ‘Cairo’. Even though schwas can be short, the last syllable of words like /lˈfʒ.rət/ ‘silver’ and /l.ˈknd.rˀət/ ‘shoe’ contrasts with the final syllable in words like /ˈta.wərt/ ‘door’, which ends in a cluster /rt/.

The negative suffix /ʃ/, optionally co-occurring with the reinforcing prefix /u/, attracts stress to the last syllable, as illustrated by /u.nq.ˈqəχʃ/ ‘I will not kill’, from /ˈnq.qəʁ/ (Figure 8, top panel). By contrast, the interrogative final clitic /a/, which expresses a neutral polar question, causes stress to be penultimate, i.e. on the syllable preceding the clitic, as shown by /a.df.ˈfu.a/ ‘An apple?’ from /a.ˈdf.fu/. As a result of this process, /jmˁ.ˈmˁa/ ‘he said’ and /ˈjm.ma/ ‘my mother’ have identical prosodic structures in their interrogative forms, /jmˁ.ˈmˁa.a/ [jmˁː![]() ː] and /jm.ˈma.a/ [jmːâː], respectively. Words with final stress retain the stress on the same syllable, as in /ˈwu.ɦa/ ‘This?’, from /ˈwuɦ/.

ː] and /jm.ˈma.a/ [jmːâː], respectively. Words with final stress retain the stress on the same syllable, as in /ˈwu.ɦa/ ‘This?’, from /ˈwuɦ/.

Intonation

All expressions so far have been assumed to have neutral (citation) intonation, which has a (rising-)falling contour over the stressed syllable rime. This includes the expressions ending in clitic /a/ discussed above, which can only be said with this intonation contour. In Figure 9, citation pronunciations of all-sonorant /ˈjm.ma/ ‘my mother’ and /jmˁ.ˈmˁa/ ‘he said’ are given in panels (a) and (d), respectively. The final stressed syllable of /jmˁ.ˈmˁa/ is closed by a glottal stop, an optional feature of emphatic pronunciation. The neutral contour contrasts with a falling-rising contour, used in polar questions with an implicational overtone, and a rising contour, used in non-final phrases. These are shown in panels (b, e) and (c, f), respectively. The f0 fall starts at the beginning of the stressed rime, as shown in panels (a) and (b) (beginning of /m/) as well as panels (d) and (b) (beginning of /a/). From this point of view, the rising contour may consist of HH% or LH%, since the final rise starts later than the beginning of the rime in both cases. Clearly, Zwara Tamazight has pitch accents and boundary tones, like English. In the case of the fall-rise, the rise goes to the end of the utterance and the fall to the beginning of the stressed rime in both panels (b) and (e). On phrase-final syllables, the falling-rising melody increases the duration of the vowel, as compared to the rising and falling melodies. This lengthening is most extreme in the case of /ə/. The duration of the voiced part before /χ/ in an isolated pronunciation of /ˈjəχs/ ‘he wants’ is around 200 ms, which may increase to 420 ms in the falling-rising intonation, with all of the lengthening going to a stationary fronted schwa, [![]() ].

].

Figure 9 Speech waveforms and f0 tracks of /ˈjm.ma/ ‘my mother’ and /jmˁ.ˈmˁa/ ‘he said’ with rising-falling intonation (panels (a) and (d)), with falling-rising intonation (panels (b) and (e)) and with rising intonation (panels (c) and (f)). All six expressions are utterance-final; those in panels (a), (c), (d), (f)) were excised from longer utterances. Male speaker AW.

Transcription of recorded passage

A translation of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ was read out by speaker AB. Below, the phonological notation of that text is given in the first line, a morphological transcription in the second line with a gloss in the fourth, while the third line gives the Tifinagh orthography. There are no letters for /mˁ nˁ lˁ rˁ ʁˁ/. Schwa is conventionally indicated, by

, to prevent the interpretation of double consonants as geminates (see section ‘Syllables’). In addition, Zwara teachers recommend the use of

for word-initial syllables consisting of schwa only, as in

/ˈə.wətt/ ‘hit:imp:sg’.

The sea wind and the sun had a discussion so as to find out who was the stronger. Then someone wrapped in a thick coat passed by. They agreed that whoever would first make him take his coat off would be the stronger. The sea wind began to blow as hard as it could, but the more it blew, the more tightly the person wrapped his cloak around him. Then the sun began to burn until it made the person take off his coat. After that the sea wind gave up. He realized that the sun was the stronger.

Abbreviations

1, 2, 3 = first, second, third person; adj = adjective; aor = aorist; f = feminine; fut = future; imp = imperative; m = masculine; nom = nominative; perf = perfect; pl = plural; prep = preposition; prog = progressive; rel = relative; sg = singular.

Acknowledgements

The data for this investigation were collected during two field trips in 2013 and 2014 as well as from a consultant in Nijmegen in 2015. I am grateful to Ayoob Sufyan for the way in which he made my visits instructive, efficient and pleasant and for introducing me to many people in Zwara. I thank Eli Afsid, Fuzia Alazaby, Mazin Alghali, Axel Bendeq, Nisrin Berico, Fadwa Helep and Nomidya Kahla for participating in a production experiment which yielded many of the data reported here. The speakers were recorded with the help of a Zoom H4n (16-bit wav) digital recorder and a ShureWH30 XLR condenser headset microphone. I thank Abderrachman Billouch and Anwr Bskal of the Centre for the Study of the Tamazight Language and Culture in Zwara for providing general support and office space, and Harry Stroomer for alerting me to the work by Terence Mitchell listed as Mitchell (Reference Mitchell, Stroomer and Oomen2009) and other work. Bendeq Willul Bendeq was an inestimable language consultant during my first visit, and my understanding of the phonological structure owes a great deal to his comments. I am most grateful to Eli Afsid for his careful vetting of my notes when he was in the Netherlands. I am happy to be able to name Muhsen Hamisi, who was recruited by my students for a phonology course assignment at Radboud University Nijmegen in 1999 and became my first consultant on what at the time appeared to me to be an unanalyzable language. (The students passed.) Sem Wijtvliet and Rooney Dahan have been most efficient in organizing transport in Libya. John Esling, Martine Grice, Maarten Kossmann, Rachid Ridouane and Timo Röttgen provided useful comments on (fragments of) a prefinal version. Milod Al-Omrani and Fathi N Khalifa kindly answered some last minute questions. Thanks are due to Ewa Jaworska, who provided formidable editorial assistance. This work was supported by the TOPIQQ grant awarded by the Volkswagenstiftung, coordinated by Martine Grice and Anne Hermes.