Introduction

The intricate regulation of transcription underlies developmental and cellular control. Transcriptional regulation occurs at many levels, including the exposure of promoters in chromatin, and the association of promoters with the transcriptional machinery. Early evidence for regulation at the level of chromatin came from the effect of the major chromatin proteins, the histones, upon transcription in vitro (reviewed in (Kornberg & Lorch, Reference Kornberg and Lorch1999)). The wrapping of promoter DNA around a histone octamer in the nucleosome represses the initiation of transcription by purified RNA polymerases (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, LaPointe and Kornberg1987). Histones cause similar repression in vivo, as shown by the depletion of nucleosomes and consequent up-regulation of transcription (Han & Grunstein, Reference Han and Grunstein1988). Repression by histones is believed to play a general role: it maintains a near-zero level of expression of all genes except those whose transcription is brought about by specific, positive regulatory mechanisms.

Promoter chromatin structure

Repression is attributed to interference with specific protein-binding. Gene activator and repressor proteins are unable to bind regulatory DNA in nucleosomes. Transcription factors are unable to form complexes with promoter DNA in nucleosomes. Relief of repression has long been attributed to the removal of nucleosomes. This view was based on the classical finding of DNase I ‘hypersensitive’ sites associated with the enhancers and promoters of active genes (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Bingham, Livak, Holmgren and Elgin1979). These sites are typically several hundred base pairs in extent, and are exposed to attack by all nucleases tested.

The classical view was challenged by results of protein–DNA cross-linking, which demonstrated the persistence of histones at the promoters of active genes. These results were extended by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), which revealed the occurrence of post-translationally modified histones at active promoters. The exposure of DNA in hypersensitive sites was reconciled with the retention of histones by the hypothesis of an altered nucleosome, whose modified structure was conducive to transcription. Chromatin remodeling was thought to involve a ‘reconfiguration’ rather than removal of the nucleosome (Paranjape et al. Reference Paranjape, Kamakaka and Kadonaga1994).

Work of the past decade has restored the classical view in a modified form. Most evidence comes from studies of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Two classes of promoters may be distinguished, those with TATA-boxes, about 20% of the total in yeast, and those without, the remaining 80%. Tightly regulated genes, such as PHO5, induced by the absence of phosphate, and GAL1-10, induced by the presence of galactose, have TATA-boxes, whereas genes that are constitutively expressed, including the so-called housekeeping genes, are ‘TATA-less’ (contain TATA-like sequences). Three promoter nucleosomes (those labeled –2 and –3 in Fig. 1, and one more upstream, to the left in the figure, not shown) are removed during transcriptional activation of the PHO5 gene (Boeger et al. Reference Boeger, Griesenbeck, Strattan and Kornberg2003), exposing a site for binding the Pho4 transcriptional activator protein (UAS2 in Fig. 1). The remaining nucleosome (labeled +1 in Fig. 1), which covers the TATA box and transcription start site (rightward arrow in Fig. 1), remains but shifts position upon activation, exposing the TATA box but continuing to cover the transcription start site.

Fig. 1. Chromatin structure of the yeast PHO5 promoter in repressed and transcriptionally activated states (from Boeger et al. Reference Boeger, Griesenbeck, Strattan and Kornberg2003). Nucleosomes N-1, N-2 and N-3 are symbolized by ovals, orange-filled, or with dashed lines following removal. Regulatory elements UAS1 and UAS2 are indicated by black-filled circles, and the TATA box is indicated by a green-filled circle. Rightward-pointing blue arrows indicate the transcription start site and direction of transcription.

The promoter chromatin structure of constitutively expressed TATA-less genes resembles that of PHO5 in the activated state. The locations of nucleosomes have been mapped genome-wide by nuclease digestion of the DNA between nucleosomes and sequencing of the nuclease-resistant fragments. A stereotypical pattern is revealed, in which coverage of the genome by nucleosomes is interrupted at promoters by nucleosome-free regions (NFRs) of about 200 bp, flanked by strongly positioned nucleosomes (Fig. 2). Positioning decays with distance from the NFR, as expected in case of a barrier to nucleosomes at the NFR (Kornberg, Reference Kornberg1981; Kornberg & Stryer, Reference Kornberg and Stryer1988). Promoters are located at the boundaries of NFRs, with TATA-like sequences exposed and transcription start sites covered by the +1 nucleosome.

Fig. 2. The distribution of nucleosomes across the yeast genome (by courtesy of Kyle Eagen). The frequency of occurrence of sequences in nucleosome monomer DNA, following micrococcal nuclease digestion and deep sequencing, is plotted against location in the genome. Open reading frames of genes and their directions of transcription are indicated by arrows beneath the plot.

Chromatin-remodeling

The removal of nucleosomes upon activation of TATA-containing promoters and removal of nucleosomes from the NFRs of TATA-less promoters are consequences of chromatin-remodeling. The existence of remodeling complexes was revealed by genetic studies of the HO and SUC2 genes of yeast (reviewed in (Winston & Carlson, Reference Winston and Carlson1992)). Mutations in five genes termed SWI and SNF, required for expression of HO and SUC2, could be suppressed by mutations in SIN genes. Sequencing revealed that a sin2 allele was a mutant form of a histone. All swi and snf mutants had similar phenotypes, and all were suppressed by sin2 mutants, leading to the proposal of a multiprotein SWI/SNF complex that opposes repression by histones.

The first isolation of SWI/SNF proteins from yeast showed their occurrence in a single complex (Cairns et al. Reference Cairns, Kim, Sayre, Laurent and Kornberg1994), including not only the original five gene products, but also six additional proteins, termed SWI/SNF-associated proteins, or Swps. The purified SWI/SNF complex could perturb the structure of a nucleosome reconstituted from purified histones and DNA, in an ATP-dependent manner (Cote et al. Reference Cote, Quinn, Workman and Peterson1994; Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Imbalzano, Khavari, Kingston and Green1994). The perturbation was transient, leaving the nucleosome essentially unaltered at the end of the reaction. The evidence for a structural alteration but with retention of the nucleosome fit nicely with the emerging idea of ‘reconfigured’ nucleosomes at transcriptionally active promoters.

Pursuit of one of the SWI/SNF-associated proteins, Swp73, led to the discovery of a second chromatin-remodeling complex (Cairns et al. Reference Cairns, Lorch, Li, Zhang, Lacomis, Erdjument-Bromage, Tempst, Du, Laurent and Kornberg1996). Swp73 has a single homolog in the yeast genome that is essential for cell growth. Fractionation of a yeast extract, monitored with the use of an antibody against the Swp73 homolog, revealed an 18-protein complex termed remodels the structure of chromatin (RSC). Six proteins are conserved between the SWI/SNF complex, RSC, and their counterparts in human cells (Phelan et al. Reference Phelan, Sif, Narlikar and Kingston1999). RSC is 10-fold more abundant than the SWI/SNF complex, and in contrast with genes for Swi and Snf proteins, genes for Rsc proteins are essential for cell growth. RSC is found associated preferentially with promoters and intergenic regions, rather than open reading frames (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Robert, Young and Struhl2002) and is specifically recruited to RNA polymerase II promoters under conditions of transcriptional activation or, in some circumstances, transcriptional repression. Many classes of genes exhibit RSC-dependence, including those involved in biosynthesis, metabolism, cell structure, chromosome structure, and transcription control (Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Huff and Cairns2008).

Purified RSC perturbs the structure of reconstituted nucleosomes with energy from ATP hydrolysis (Cairns et al. Reference Cairns, Lorch, Li, Zhang, Lacomis, Erdjument-Bromage, Tempst, Du, Laurent and Kornberg1996). RSC catalyzes both sliding of a nucleosome, whereby a histone octamer translocates along a DNA molecule (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, Zhang and Kornberg2001), and the removal of a nucleosome, in which the histone octamer is transferred to a chaperone protein or naked DNA (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, Zhang and Kornberg1999). The largest subunit of RSC, Sth1, is an ATP-dependent DNA translocase. It acts at a site two double helical turns from the dyad axis of the nucleosome, drawing DNA in from one side and expelling it on the other (Saha et al. Reference Saha, Wittmeyer and Cairns2005). Close counterparts of RSC have been identified in humans and other eukaryotes. Structural and mechanistic studies have borne out the close relationship between yeast RSC and SWI/SNF complexes and the corresponding human complexes (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Nogales and Ciferri2010).

RSC–nucleosome complex

The structure of a RSC–nucleosome complex has been investigated by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and biochemical analysis. A cryo-EM reconstruction at about 25 Å resolution (Chaban et al. Reference Chaban, Ezeokonkwo, Chung, Zhang, Kornberg, Maier-Davis, Lorch and Asturias2008) showed RSC largely surrounding the nucleosome (Fig. 3). RSC was not much affected by nucleosome-binding, but the structure of the nucleosome was altered. Much of the DNA was displaced from the surface of the histone octamer and was presumably in contact with RSC. One of the two H2A–H2B dimers was apparently displaced from its normal position as well.

Fig. 3. Cryo-EM structure of RSC–nucleosome complex (from Chaban et al. Reference Chaban, Ezeokonkwo, Chung, Zhang, Kornberg, Maier-Davis, Lorch and Asturias2008). (a) X-ray structure of histone hexamer (histone octamer lacking one H2A–H2B dimer) docked to the central cavity of a cryo-EM map of RSC (yellow mesh), showing the close fit of the histones to the cavity. The histone hexamer is shown in space-filling representation (with histones H2A yellow, H2B red, H3 blue and H4 green) calculated at 25 Å resolution from the X-ray structure of the nucleosome (Luger et al. Reference Luger, Mader, Richmond, Sargent and Richmond1997). (b) A view of the RSC-nucleosome complex nearly perpendicular to the view in (a), showing only RSC density in a slab including the central plane of the nucleosome, indicated by the dotted rectangle in (a). Difference density between cryo-EM maps of RSC–nucleosome complex and RSC alone is shown in blue mesh. RSC protein densities in close contact with the nucleosome are designated 1–3. Density (1) likely corresponds to the position of the Sth1 ATPase subunit, and lack of DNA density adjacent to this location (red arrow) suggests that binding of Sth1 pulls DNA away from the histones. DNA is represented by a black line, with regions where no DNA density is apparent in the RSC–nucleosome reconstruction indicated by dashed lines.

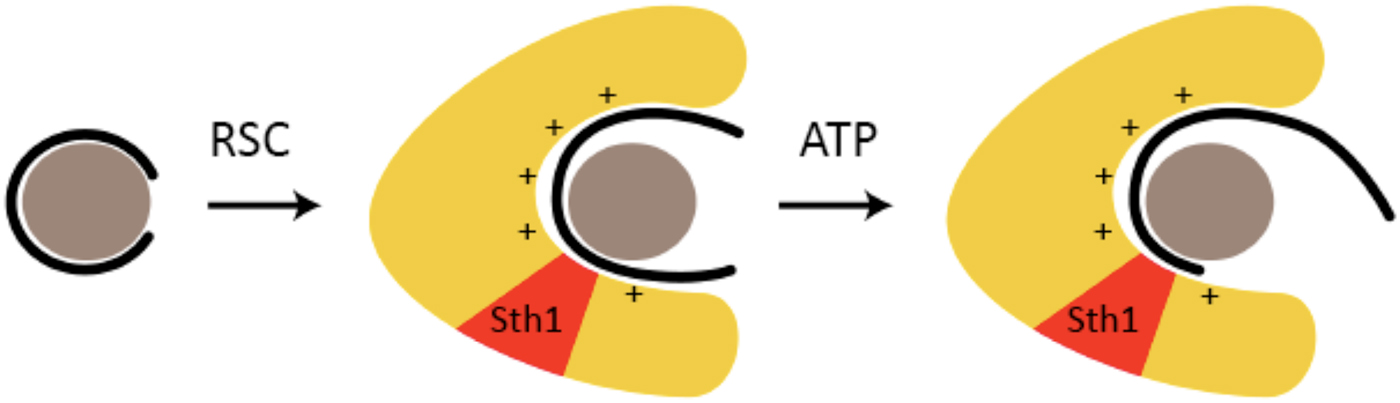

The conclusions from cryo-EM were supported by results of DNase digestion (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, Maier-Davis and Kornberg2010). RSC-binding exposed nucleosomal DNA to cleavage by DNase I, and allowed penetration of exonuclease III almost all the way to the dyad. These results were attributed to release of DNA from the surface of the nucleosome and interaction with RSC. The DNA is transferred from fixed sites on the histone octamer to a positively charged surface of RSC (Fig. 4). The DNA is mobilized, enabling the translocation process. Binding energy suffices for mobilization; ATP hydrolysis drives translocation. Evidence for a positively charged, DNA-binding surface of RSC has come from measurement of RSC–DNA interaction. RSC binds DNA with about the same affinity as a nucleosome (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, Cairns, Zhang and Kornberg1998). DNA-binding is unaffected by ATP, whereas RSC–nucleosome interaction is greatly enhanced, reflecting the involvement of additional RSC–nucleosome contacts in the translocation process.

Fig. 4. RSC-binding displaces DNA from the nucleosome, enabling translocation (based on (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, Maier-Davis and Kornberg2010)). A nucleosome is symbolized by a gray sphere (histone octamer) surrounded by a black line (DNA). RSC is symbolized by a yellow horseshoe-shaped region, with the location of the Sth1 subunit indicated in red. The presumed positively charged surface of the RSC cavity, to which DNA is transferred from the nucleosome upon RSC–nucleosome interaction, is indicated by + signs.

Role of RSC in the formation of NFRs

The first evidence of proteins responsible for NFR formation came from the identification of Grf2, later renamed Reb1, which binds to a specific site in many yeast promoters. Reb1-binding creates an NFR and, when combined with a T-rich sequence, greatly enhances transcription (Chasman et al. Reference Chasman, Lue, Buchman, LaPointe, Lorch and Kornberg1990; Fedor et al. Reference Fedor, Lue and Kornberg1988). A similar finding was made by deletion analysis of the SNT1 promoter, showing a requirement for a 22 bp DNA element, containing a Reb1-binding site and T-rich sequence, for NFR formation (Hartley & Madhani, Reference Hartley and Madhani2009; Raisner et al. Reference Raisner, Hartley, Meneghini, Bao, Liu, Schreiber, Rando and Madhani2005). Insertion of the 22 bp DNA element in the open reading frame of an unrelated yeast gene resulted in the formation of an NFR at the ectopic site. Involvement of RSC was demonstrated by incorporation of a degron in the Sth1 subunit and expression in a temperature-sensitive degron system. Depletion of RSC at a restrictive temperature caused the loss of the NFR from the ectopic site. Depletion of RSC also led to a marked diminution in size of NFRs genome-wide in yeast (Hartley & Madhani, Reference Hartley and Madhani2009).

The role of the T-rich sequence in NFR formation emerged from a recent study of RSC activity in vitro (Lorch et al. Reference Lorch, Maier-Davis and Kornberg2014). It had been repeatedly observed that NFRs contain an abundance of T-rich sequences, including poly(dA:dT) tracts of various size, and the formation of NFRs was attributed to a destabilization of nucleosomes by poly(dA:dT) DNA. Examination of NFR sequences, however, revealed many which contain no poly(dA:dT) tracts, and measurement of stabilities of nucleosomes showed no difference between NFR and open reading frame DNA. Rather, poly(dA:dT) tracts stimulate the removal of nucleosomes by RSC and ATP.

The results from studies of Reb1, T-rich sequences, and RSC may be interpreted in two ways. Reb1 may bind to its recognition sequence and recruit RSC, whose activity is stimulated by an adjacent T-rich sequence, resulting in the removal of a nucleosome and formation of an NFR. In support of this idea, it has been noted that a proteome-wide study showed evidence of Reb1–RSC interaction. Alternatively, a T-rich sequence promotes the removal of a nucleosome by RSC, exposing the site for the binding of Reb1, which provides a barrier to nucleosomes, creating the NFR and positioning adjacent nucleosomes. Further work is needed to distinguish between these possibilities.

Interaction of RSC with the +1 nucleosome

As mentioned above, regulatory and promoter elements lie in NFRs, or they are exposed by the removal of nucleosomes from inducible promoters, but transcription start sites lie within the adjacent ‘+1’ nucleosome Fig 1. Two recent studies have demonstrated a perturbation of structure of the +1 nucleosome, and have implicated RSC in the process. Incorporation of a copper-phenanthroline moiety in histone H4 and cleavage of the associated DNA with hydrogen peroxide revealed a pronounced asymmetry of +1 nucleosomes (Ramachandran et al. Reference Ramachandran, Zentner and Henikoff2015): cleavage was more frequent on one side of the dyad axis of the nucleosome than on the other. By contrast, the vast majority of yeast nucleosomes showed only symmetric cleavage. A similar asymmetry was noted in the pattern of micrococcal nuclease digestion of +1 nucleosomes. These findings were attributed to partial unwrapping of DNA from the +1 nucleosome. It was further shown that RSC is associated with asymmetric +1 nucleosomes and instrumental in transcription of genes with such asymmetric nucleosomes.

A second study employed ChIP for mapping contacts of histones with nucleosomal DNA (Rhee et al. Reference Rhee, Bataille, Zhang and Pugh2014). An asymmetry in the abundance of contacts was observed for the +1 nucleosome. In both studies, the direction of the asymmetry was uncorrelated with the direction of transcription, with partial unwrapping of about half the nucleosomes on the upstream side and half on the downstream side. ChIP has also given evidence for interaction of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery with the +1 nucleosome (Rhee & Pugh, Reference Rhee and Pugh2012).

The loss of histone–DNA contacts in a complex of RSC with the +1 nucleosome in vivo may be explained by the transfer of DNA from histones to RSC in a complex formed in vitro (Fig. 4). The question arises of why DNA translocation, and consequent nucleosome sliding or loss, does not occur in the RSC–nucleosome complex in the presence of ATP in vivo. The answer may relate to histone posttranslational modifications, to additional proteins, or to other, as yet unidentified factors.

Conclusions and outlook

Chromatin-remodelers, exemplified by yeast RSC, relieve repression by nucleosomes in a two-stage process. RSC removes nucleosomes in an ATP-dependent manner to expose regulatory and TATA-box (or TATA-like) sequences. And RSC binds the adjacent ‘+1’ nucleosome, which covers the transcription start site(s), partially unwrapping the nucleosomal DNA. It may be supposed that subsequent activator-binding to regulatory elements leads to removal of the +1 nucleosome and the initiation of transcription.

The stepwise relief of repression by the nucleosome is both surprising and advantageous. It had been thought that chromatin-remodeling of inducible genes exposed the entire promoter for transcription. And it was assumed that the +1 nucleosome is removed from all genes before entry of the transcription machinery. Instead a nucleosome covers transcription start sites following the activation of inducible genes, and the +1 nucleosome is retained on all transcribed genes. These unexpected features may be advantageous for tight control by the nucleosome, minimizing spurious transcription, and at the same time creating a poised (partially unwrapped) state of the +1 nucleosome for the facile initiation of transcription.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by NIH grants GM36659 and AI21144.