What happens to social protests when a country undergoes a political transition from authoritarianism to democracy? Non-democratic regimes restrict political expression and do not tolerate collective actions. Protests sparked by minor incidents, such as the self-immolation of a Tunisian fruit peddler, can catalyse mass mobilizations. Once authoritarian rulers are removed, will protest behaviour decline because of the disappearance of repression, or will it flourish in a more tolerant environment? Are protesters going to raise more radical demands and adopt bolder tactics, or will they become more moderate by relying more on the channels of electoral politics? Our inquiry here points to the opposite of what has been identified as the ‘repression–dissent nexus’ (Lichbach Reference Lichbach1987; Steinert-Threlkeld et al. Reference Steinert-Threlkeld2022) or ‘repression paradox’ (Chang Reference Chang2015) in the literature. Repression generally deters protest-making by raising the cost of collective action, but it at times backfires by radicalizing protest activism. Does such indeterminacy also exist for democratization?

Previous studies indicate that social protests evolve into a more institutionalized status in established democracies (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2004; Rucht and Neidhardt Reference Rucht and Neidhardt2002; Soule and Earl Reference Soule and Earl2006); building on these insights, our article focuses on identifying the mechanisms that transform protests into a permanent and stable feature in newly democratized countries. We are interested in shifts in movement tactics and protest violence. In analysing the impact of democratization, we also bring the variables of mobilizing structure (participant numbers and organizational leadership) and political opportunity structure (ruling-party orientation and politician involvement) into consideration. To anticipate the conclusion, we maintain that democracy ‘contentiously institutionalizes’ social protests. Demonstrations and rallies become an everyday phenomenon as well as a vehicle for advancing different kinds of interests and identities. Protest gatherings become peaceful because participants exercise more self-restraint. Confrontational tactics give way to highly symbolized actions in order to express demands. Yet, protests remain equally explosive, and the involvement of parties or politicians frequently occurs.

The observation country here is Taiwan, a successful case of democratization after 38 years of one-party martial-law rule (1949–1987). We collect, code and analyse protest events taking place on Taipei's Ketagalan Boulevard, the space in front of the Presidential Office, from 1986 to 2016. This area has been a mecca for protesters ever since the Taiwanese people were first allowed to take to the streets. The way in which Taiwanese people have marched on Ketagalan Boulevard over three decades provides a meaningful microcosm to gauge the impact of democratization on those protest activities that are related to national-level politics, although they are not representative of all protests in the statistical sense.

This article will discuss the existing literature in order to construct hypotheses on democratization and protests. Then we will elaborate on the research methods for data collection and analysis. We adopt the coding protocol developed in the Dynamics of Collective Actions (DOCA), a research project initiated by leading scholars to extract events data from Taiwan's news database.Footnote 1

Protest evolution in three perspectives

Three streams of literature provide the departure point for our study: political transition theory, the institutionalization thesis and networked movement theory. We select these three perspectives because they represent the mainstream understanding of the long-term evolution of protests. All of them share the macrostructural focus, but they diverge in their predictions.

First, scholars of political transition theory, or ‘transitology’, examine the role of protests in authoritarian-to-democratic transitions in Latin American, South and East European countries (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; O'Donnell and Schmitter Reference O'Donnell and Schmitter1986; Przeworski Reference Przeworski and O'Donnell1986). A typical transition usually begins with an external shock to the old regime that resuscitates civil society actors. As bottom-up activism picks up, a popular upsurge is critical to push the reluctant incumbents to accept more sweeping reforms. This intensified period of protest activities is transient and will be replaced by more conventional forms of participation, such as elections and lobbying. As opposition leaders obtain insider status, they begin to demobilize their constituencies (Hipsher Reference Hipsher and Giugni1998; Oxhorn Reference Oxhorn1991). Once democracy is achieved, anti-authoritarian struggles lose their raison d’être, and campaigns for other causes find it more difficult to attract supporters. Those activists who fail or refuse to adapt to the new political rules will be gradually marginalized.

While political transition researchers anticipate the decline of protest activism as a corollary of democratization, what we identified as the institutionalization thesis offers a contrasting appraisal from observations of established democracies in North America and West Europe. Social movements have become routinized, rather than disappearing. Based on the observation of the aftermath of the long 1960s, David Meyer and Sidney Tarrow (Reference Meyer, Tarrow, Meyer and Tarrow1998) maintain that a ‘social movement society’ has emerged because protests have become perpetual, more frequent and diffused spatially and to different sectors. Democratic regimes increasingly adopt a rule-based policing approach to demonstrations and rallies, thereby removing the source of uncertainty (della Porta Reference della Porta1995). Inheriting the insights from resource mobilization theory (Zald and McCarthy Reference Zald and McCarthy1987), this view stresses the proliferation of movement-related organizations and the concomitant professionalization, albeit not in the direction of bureaucratic formalization (Meyer and Tarrow Reference Meyer, Tarrow, Meyer and Tarrow1998: 17). In addition, its proponents emphasize the significance of right-wing and conservative counter-movements (Banaszak and Ondercin Reference Banaszak and Ondercin2016; Whittier Reference Whittier2009), making street protests more ideologically diversified. There is an increasing recognition that protests and voting are not two disconnected forms of political participation, as elected politicians often initiate their own protests, and grassroots campaigning affects the agenda of mainstream parties (McAdam and Kloos Reference McAdam and Kloos2014; McAdam and Tarrow Reference McAdam and Tarrow2010). In short, institutionalization expects protests to become an enduring feature of modern democracy (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2004; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2021).

Finally, the third stream of literature is more expansive in scope as it looks at the global justice movement (Smith Reference Smith2008), colour revolutions (Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011) and the worldwide wave of insurgence in the wake of the Arab Spring (Bayat Reference Bayat2017; della Porta Reference della Porta2020). Manuel Castells (Reference Castells2015) proposes the notion of ‘networked movements’ to understand their horizontal characteristics, as hierarchical organizations (mass parties, labour unions and professional social movement organizations) have been absent from these eventful protests. The progress of digital communication enables the emergence of the so-called ‘connective actions’, replacing the previous paradigm of organization-led ‘collective actions’ (Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segerberg2013). Aside from technological factors, observers see the presence of a culture of grassroots participation and the rejection of the instrumental mentality (Juris Reference Juris2008; Maeckelbergh Reference Maeckelbergh2011). Networked movements are said to proliferate globally without relying on pre-existing organizations. The sources of grievance are highly diversified, as they can be about an unwanted policy, an unfair election or an unpopular leader. Networked movements are typically non-programmatic or diffuse in their demands (Krastev Reference Krastev2014). Their actions are noted for being spontaneous and expressive. Some protests even take pride in being ‘leaderless’ (Graeber Reference Graeber2013) or proceed under so-called ‘soft leadership’, which is less authoritative but more expressive and interactive (Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2012).

Theorists of networked movements are sceptical of organizations and leadership, and this understanding is shared among an emerging research focus on mobilization under unusually harsh repression. Participants are conscious of the high risk, and thus they ‘individualize’ their grievances and feign ideological conformity (Fu Reference Fu2017). Participants might also ‘mobilize from scratch’ by intensively using their everyday social ties (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2021). Although two streams of literature are concerned with different issues, they concur that pre-existing organizations are not a requisite for protest activism.

The three theoretical perspectives examined above offer contrasting predictions about the evolution of protests. In the following, we will construct research hypotheses by gleaning from their insights. We notice that most previous studies are interested in the question of how protests and political contention affect democratic transition (Kadivar Reference Kadivar2017; Quaranta Reference Quaranta2015; Su Reference Su2015). The causal concern here is the opposite in that we attempt to understand how the advent of democracy restructures protest behaviour.

Democratization and protest violence

Protest violence takes place when protesters take offensive actions to destroy property and harm other people in order to realize their goals (della Porta Reference della Porta2014). Authoritarian rulers outlaw peaceful expression so that citizens feel that they have to take drastic action to have their voices heard. As Martin Luther King famously said, ‘violence is the voice of the unheard’. Democracy grants political freedom to citizens, and they are less likely to be in a desperate situation requiring them to resort to high-risk actions to assert their own rights. Protesters' use of aggressive tactics can be counterproductive because they might end up alienating public opinion and becoming an easy target for government repression. Using peaceful means helps project a positive public image and thereby avoids the stigmatization of protesters as irrational (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor2009). As a contrasting case, Hong Kong's 2019–2020 protest movement, a popular struggle against de-democratization imposed by China, indicates that growing coerciveness resulted in greater acceptance of protest violence (Lee et al. Reference Lee2021; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu2022). As such, we anticipate the following:

Hypothesis 1: As democratization proceeds, the probability of protest violence will decrease.

Mediating variables

Political opportunity structure (POS) refers to those institutional characteristics of a political regime that have an impact on movement mobilization (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1986; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011). A more favourable POS encourages protest participation either because it lowers the cost of collective action or because it makes movement success more likely. It follows that the transition from authoritarianism to democracy is nothing less than a major change in POS. As citizens gain civil liberties and political rights, they find it easier to mount a protest action. Two features of POS need to be taken into consideration.

A functioning democracy entails regular changes of the ruling party via popular vote. The ideological orientation of the politicians in power has implications for activists on the street. Liberal incumbents are typically more tolerant of unruly protests, and conservative administrations tend to adopt a law-and-order approach and see movement activism as a civil disturbance (Jenkins et al. Reference Jenkins2003). We expect that when liberals are in power, protesters are less likely to use violent means.

Hypothesis 2a: When the ruling party is liberal, protest violence will decrease.

Politicians' involvement in protests should not be seen as an aberration, but rather a constant feature under democracy. Making protests and canvassing for votes are both means to promote political changes, and the boundary between institutional and extra-institutional participation is always blurry (Goldstone Reference Goldstone2004; Markoff Reference Markoff2011). Since opposition politicians have more incentive to ‘rock the boat’, they are more likely to initiate their own protests or sponsor existing ones. As political parties possess members and other resources that are denied to other social movement organizations (SMOs), their involvement is bound to increase the political salience of the protest. With the backing of politicians, participants are emboldened to use violence.

Hypothesis 2b: The involvement of opposition parties increases the probability of protest violence.

Scholars have long been interested in how the mobilizing structure, or organizational characteristics of participants, affects movement outcome (Zald and McCarthy Reference Zald and McCarthy1987). We look at two variables in particular. First, the number of participants matters. There is safety in numbers, and people become more willing to do something that they would avoid if they were on their own. We hypothesize that a protest event with a greater number of participants will embolden participants to use violence:

Hypothesis 3a: As the number of participants increases, the probability of protest violence will increase.

The same perspective also expects social movements to gravitate towards a more permanent status. The rise of professional SMOs plays a critical role, as their leaders are more concerned with long-term goals, rather than taking risk in a single clash. Organizational leaders are conservative in the sense that they tend to avoid unplanned disruptive behaviours and prefer negotiation with the authorities (Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1993). We expect that violence will decrease where more organizations are included.

Hypothesis 3b: As more organizations are involved, the probability of protest violence will decrease.

Data and methods

The data set is collected from the two largest Chinese-language newspaper databases in Taiwan, the United Daily News and the China Times. The news drawn from the United Daily News spanned from 1986 to 2016, and the news from the China Times spanned from 1994 to 2016.

We collected the articles reporting events that occurred on Ketagalan Boulevard by using the road name (both the current name and the previous one) as the keyword in the online search. After filtering, we gathered 1,585 news articles for 421 events.Footnote 2 They do not include every incident of contentious politics in the area because smaller events are not sufficiently newsworthy to be covered by the media. Our research does not claim exhaustiveness, but we are confident that the major protests are included and they constitute a representative subset in Taiwan's political transition.

We manually coded various aspects of the protest events. Our coding is based on the activities list provided by the DOCA project. Taiwan's Presidential Office Building was originally the office of the governor-general in the Japanese colonial era (1895–1945). After the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was defeated by their communist rivals, the KMT government withdrew to Taiwan, inheriting the colonial and autocratic structure. The KMT turned the colonial building into the Presidential Office in 1950 and the road in front of the building was renamed Jie Shou Road (‘Longevity for Chiang Kai-shek’). Jie Shou Road and its surroundings teem with governmental agencies, representing the spatial centre of political power in Taiwan. The KMT re-engineered the landscape by removing evidence of Japanese heritage and adding Chinese-style architecture (Allen Reference Allen2007). Following liberalization in the mid-1980s, the road in front of the Presidential Office immediately became a magnet for protest-making. Demonstrators attempted to show top leaders their discontent, and such a choice of venue also helped attract media attention. In 1996, the opposition party city mayor renamed the road Ketagalan Boulevard, adopting the name of an Austronesian indigenous people. The name change reflected Taiwan's march towards democracy as well as the accompanying indigenization in identity. Given the rich political connotations, marching on Ketagalan Boulevard is comparable to rallies at the Lincoln Memorial in the many marches on Washington in American history (Barber Reference Barber2002).

Variables

Dependent variables

We select two dependent variables for observation: protest violence and protest tactics. Protest violence occurs when protesters use force to destroy property or harm other people. It is coded as a dummy variable, with 1 referring to its presence and 0 its absence.

Violence is of course a protest tactic, but so are the peaceful rallies and demonstrations that have become conventional, or what Tarrow (Reference Tarrow1994: 31–47) identifies as ‘modular collective action’. Violence involves a high level of disruptiveness, with protesters using aggressive and offensive means (Wang and Soule Reference Wang and Soule2016). As well as this, we are also interested in non-confrontational tactics, among which we pay particular attention to festive and performative ones. Notwithstanding Charles Tilly's (Reference Tilly1997) notion of ‘repertoire’, which highlights the fact that all collective actions (violent or not) involve staged and scripted presentation of participants' claims, there are some protests that are more culturally and artistically elaborated. As Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan (Reference Chenoweth and Stephan2011: 36) pointed out, a ‘festival-like atmosphere’ has the effect of ‘enhancing participation in nonviolent campaigns’.

In our definition, performative tactics attempt to express protesters' demands with dramaturgical actions, such as staging a concert or a street dance, while festive ones deliberately downplay hostility by highlighting the joyful moments of acting together, for example launching paper airplanes, releasing balloons, flying sky lanterns, projecting laser beams onto official buildings, holding street fairs or staging a roadside wedding banquet (for same-sex couples). We do not assume that it is only protesters in democracies who can afford to be creative. Authoritarianism makes protests costlier, and as such, participants need to be innovative enough to spread their messages without exposing their personal identity. They often have to practice what James Scott (Reference Scott1990) identified as the ‘art of resistance’ for disguise. In democracies, we expect that movement creativity is more geared towards public display with the ostentatious use of festive and performative tactics. We choose performative and festive tactics because they are at the opposite extreme to confrontational tactics, either in terms of symbolism (rather than physicality) or intended emotion (joy rather than fury). Since these two tactics partially overlap in meanings and may be co-present in the protests, we construct a new variable of festive and/or performative tactics to avoid the redundant calculation of their interaction.

Independent variables

We choose the polity scores of the Polity5 data set as the indicator of democratic transformation. The data set is the latest version of the Polity Project, established by Ted Gurr in the 1970s, and now contains annual data for 167 countries from 1800 to 2018. It is said to be ‘the most widely used resource for monitoring regime change and studying the effects of regime authority’ (Marshall and Gurr Reference Marshall and Gurr2020: 1).Footnote 3 Regime scores range from 10 (strongly democratic) to −10 (strongly autocratic), and Taiwan's score transitions from −7 in 1986 to 10 in 2016, signifying a sweeping transformation from autocracy to democracy. Since political change takes time to make its impact felt, we treat democratization as a leading variable by using the democratic index of the preceding year (t − 1).

Two variables related to political opportunity structure are also taken into consideration. Taiwan's political landscape is dominated by two mainstream parties, the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The main cleavage between the two revolves around relations with China, with the KMT advocating for a closer relationship with the mainland, while the DPP leans towards independence. The two parties also differ in terms of other social issues and political values. The KMT is more conservative when it comes to human rights, environmental protection and gender equality, whereas as the heir of the opposition movement, the DPP appears more liberal (Buchanan and Nicholls Reference Buchanan and Nicholls2003; Chi Reference Chi2014; Huang and Sheng Reference Huang and Sheng2022). We hypothesize that the ruling party's orientation will affect the generation of protests (Hypothesis 2a).

Both of the main parties and their politicians are involved in protests when in opposition, which can result in the use of protest violence. Politicians from smaller parties are often present at the protest scene, including the Taiwan Solidarity Union and the Taiwan Independence Party (ideologically closer to the DPP) and the New Party and the People First Party (allies of the KMT). If an event involves opposing political parties or politicians, it is coded as 1, and 0 otherwise.

We set two mobilizing structure characteristics, the number of protest participants and the number of involved SMOs, as independent variables. As newspaper reports rarely provide a precise calculation of the number of participants or a complete roster of sponsoring organizations, we use an ordinal level of measurement instead. The number of participants is measured by a logarithmic scale with 1 for fewer than 100 participants, 2 for 100 to 999 participants, 3 for 1,000 to 9,999 participants, 4 for 10,000 to 99,999 participants, and 5 for 100,000 and more. As for the number of SMOs, we code the variable 0 for the absence of organizations, 1 for only one organization involved, and 2 for two or more organizations involved. The presence of more than one SMO indicates a higher degree of preparedness for the event since it involves inter-organizational coordination.

Figure 1 plots the yearly distribution of the numbers of all protests and protest violence alongside Taiwan's steady march towards democracy. The protests demonstrate a wave-like development and remain a persisting phenomenon even after the country reached full democracy. While protest violence appears infrequent, it fluctuates and tenaciously stays.

Figure 1. Yearly Distribution of Protests and Protest Violence

Control variables

Prior studies indicate that economic transformation contributes to the formation of collective actions. Under the sway of neoliberal globalization, structural adjustment and austerity programmes saw citizens' living conditions deteriorate, causing the rise of unemployment and social inequalities (Fominaya Reference Fominaya2014; Yagci Reference Yagci2017). Chronic youth unemployment and income inequality, for instance, triggered the Arab Spring.

Three macro-economic structure variables are added to our analysis as control variables: annual growth rate, annual unemployment rate and annual Gini coefficients (for measuring income inequality). We also use the indexes prior to the year in which a protest event took place (t − 1).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the variables in our 421 protest events.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

Note: Number of observations = 421.

Protest violence only accounts for 13.3% (56 events) of our sample. In terms of movement claims, political protests (28 events), labour protests (8 events) and peasant protests (7 events) make up the bulk. Political protests involve ongoing salient controversies and are frequently led by politicians. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, DPP politicians typically played a leading role in pushing for more democratic reforms; after the first power turnover in 2000, KMT politicians emerged as the leader in the major incidents of post-election protests in 2000 and 2004, and in the protest against DPP President Chen Shui-bian's financial irregularities in 2006. Of all political protests (127 events in total), 22% used violence – the highest percentage of all claims. As said, our definition of protest violence follows the procedure of the DOCA research project by looking at intended personal harm and property damage. Our sample documents 30 cases of personal injury, 32 cases of property damage and 26 cases of both.

Being the opposite of political violence, festive tactics made up 14.5% of protests, and performative 38.5%. Also, 24.7% of the protest events witnessed the participation of opposition parties or politicians, and 46.6% of the events involved interorganizational collaboration (Table 1). In terms of participant numbers, our sample is skewed towards smaller incidents as events with fewer than 1,000 participants make up more than half of cases (54.4%). SMO involvement is evenly distributed. There are 13.1% of events without SMOs, while 74.8% of them saw the participation of only one SMO, and 12.11% have two or more SMOs.

On the whole, protests in front of Taiwan's Presidential Office are largely peaceful, reflecting the island nation's less tumultuous path towards democracy. In part, Taiwan's former authoritarian regime was less despotic, giving rise to a moderate political opposition movement (Cheng Reference Cheng1989). Movement leaders were less likely to adopt drastic means and accepted the philosophy of non-violent resistance. For instance, the 2014 Sunflower Movement, a three-week protest that occupied the national legislature to oppose a free trade agreement with China, was largely non-violent and received popular support (Ho Reference Ho2015).

Logistic regression analysis

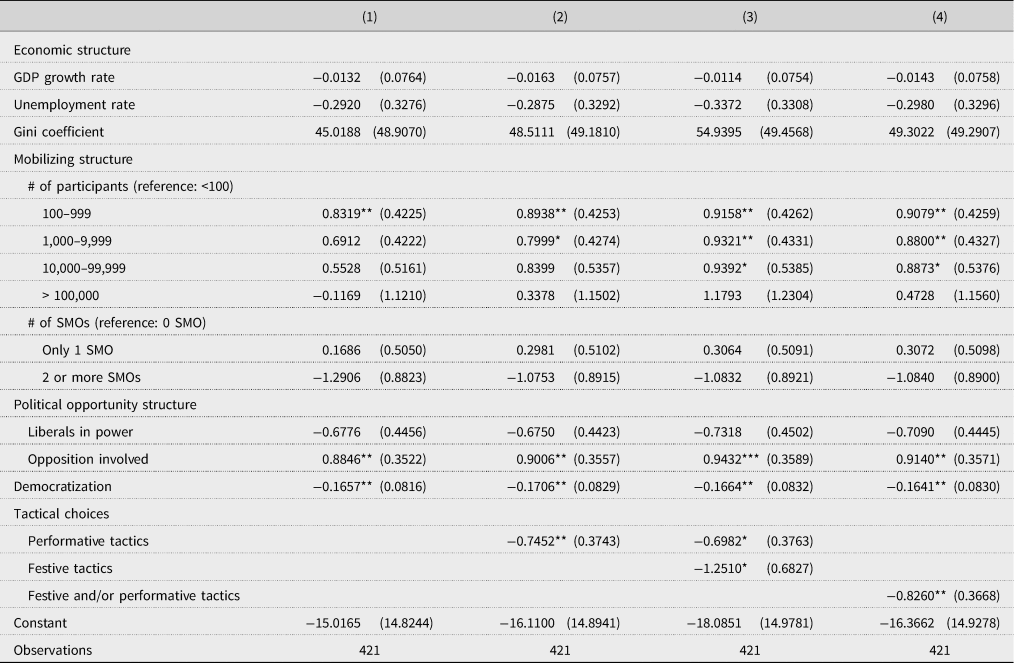

Table 2 presents the logistic regression on protest violence, while Table 3 shows the logistic regression on tactical choice.

Table 2. Logistic Regression on Protest Violence

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table 3. Logistic Regression on Non-confrontational Tactical Choices

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The variable democratization is found to be associated with a decrease in protest violence (Table 2: Models 1–4). The tests are statistically significant, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. When it comes to tactical choice, there is no significant association between democratization and festive and performative ones (Table 3: Models 5–7). Our analysis finds that the ruling-party orientation explanation is weak. Having the DPP in power appears to discourage protest violence, but none of the test results was statistically significant (Table 2). We reject Hypothesis 2a accordingly. The presence of opposition parties exerts a significant and positive effect on protest violence (Table 2), thus supporting Hypothesis 2b.

We find the political opportunity variables have uneven predictive power. Whether liberals or conservatives control the national government does not have a perceptible influence on the dynamics of protest. However, once opposition politicians lead rallies or are present on the scene, the likelihood that protesters use violence will increase.

The number of participants is positively and significantly associated with protest violence (Table 2). However, as the number of protesters increases, the likelihood of violence rises initially, but has no statistically significant increase after reaching a tipping point. When the number of participants exceeds 100 people, the probability of violent occurrences increases compared to the events with fewer than 100 participants. The effects of participant size do not extend to events having 10,000 and more participants. Thus, Hypothesis 3a is sustained, and there exists a curvilinear relationship, as protest is more likely to take place in a medium-sized crowd.

The number of participants is positively and significantly associated with the use of festive and performative tactics (Table 3). Compared to the events with fewer than 100 participants, when the number of participants expands to 100–999 people, the probabilities of using performative or festive tactics do not increase with statistical significance. However, when the number of participants surpasses the threshold of 1,000, the likelihood of choosing performative or festive tactics increases with statistical significance. It is worth noting that all the events having more than 100,000 participants have at least performative or festive tactical choices, thus the category of the events having more than 100,000 participants is omitted in Model 7.

The number of SMOs has no statistically significant associations with the probability of protest violence (Table 2), thus rejecting Hypothesis 3b. Although the number of SMOs is not associated with the adoption of festive tactics with statistical significance, it is significantly and positively associated with the adoption of performative tactics.

We have mixed results from the mobilizing structure variables. A protest that has more participants is more likely to result in protest violence before reaching a threshold of 10,000 participants (Hypothesis 3a). It is interesting that the threshold also appears in the adoption of performative and festive tactics: an increase in the number of participants has no statistically significant effects until the size surpasses 10,000 participants.

Although the number of SMOs has no statistically significant association with the likelihood of protest violence and thus Hypothesis 3b is rejected, it shows statistically significant and positive effects on the adoption of performative tactics.

Our statistical model places tactical choices in an intermediate position between macro-structural changes and protest results. The above sections have discussed how democratization, political opportunity structure and mobilizing structure variables determine the choice of tactics. They, in turn, also affect protest violence.

When protesters decide to use non-confrontational tactics such as performative and festive tactics, the result is likely to suppress the occurrences of protest violence (Table 2: Models 2–4). However, while festive and performative tactics are likely to reduce protest violence, only performative tactics are statistically significant at the 0.05 level in Model 2 (the p-values of performative and festive tactics in Model 3 are respectively 0.064 and 0.067) (Table 2). When performative and festive tactics are combined into the same category, the union of performative and festive tactics (adopting at least either one) has a statistically significant and strongly negative association with protest violence (Table 2: Model 4).

Discussion: how democratization makes a social movement society

Our inquiry began with three contending perspectives (political transition theory, the institutionalization thesis and networked movement theory) on the long-term evolution of social protests in Taiwan. How do these theoretical predictions fare in our statistical tests?

Political transition theorists anticipate the decline of protests once democracy is consolidated as the ‘only rule in the game’. The steady decrease of protest violence in the three decades of Taiwan's march towards democracy appears to support this view. However, protest-making remains a perennial channel of political expression. Mass rallies and demonstrations on Ketagalan Boulevard have not simply disappeared but have instead become an everyday phenomenon under the nascent democracy. Political transition theory errs in privileging institutional participation (political parties and elections) over extra-institutional ones. Our study reveals that the involvement of opposition politicians in protests emerged as a constant feature and their presence increases the probability of protest violence. Violence continues to exist as Taiwan's democracy score increases, suggesting that disruptive protest remains an option for those who have no other possibilities. Political transition theory is excessively optimistic about the absorbing capacity of democratic institutions.

In contrast, both the institutionalization thesis and networked movement theory expect a proliferation of protests, but for different reasons. The former expects the rise of SMOs and their growing influence in patterning protests towards a more predictable and routinized direction, while the latter envisions a rather amorphous diffusion of protests without organizational mediation as movement activism becomes more spontaneous and self-organized. Our sample reveals the profound effects brought about by organizations. Less than 14% of the protests in Ketagalan Boulevard are not sponsored by an existing organization, which means the majority of the events are planned and prepared for in advance. However, we find that organizational leadership has mixed effects: it does not directly help reduce the likelihood of protest violence, but encourages the use of performative tactics that suppress the likelihood of protest violence. Contrary to the prediction on the imminent death of organizations in protests and their replacement by smart crowds (Shirky Reference Shirky2008), ‘invisible insurgents’ (Invisible Committee 2009) and the ‘multitude’ (Hardt and Negri Reference Hardt and Negri2017), pre-existing organizations continue to play an important role in patterning the contemporary dynamics of protests.

Our observation lends support to the institutionalization thesis, which expects the normalization of protests under democracy as well as an increasingly larger role for SMOs and the continuing involvement of politicians. Proponents of this perspective expect social protests to take a moderate turn marked by less frequent use of violence. Nevertheless, when the idea of the institutionalization of protests was first raised at the turn of the last century (Meyer and Tarrow Reference Meyer, Tarrow, Meyer and Tarrow1998), Western democracies had already been consolidated long before the onset of the 1960s protest wave. By contrast, newly democratized countries like Taiwan are capable of telescoping three processes nearly within the same period: the transition to democracy, the institutionalization of protests and the rise of SMO leadership. Late-democratizing countries can catch up with the latest status of contentious politics. The making of a social movement society in the West took a longer route; yet, in a successful late-democratizing country like Taiwan, it took less than 30 years.

Our findings lead us to rethink one of the earliest and most central tenets in the political transition theory, which narrowly looks at the development of formal institutions and relegates civil society to a secondary position. For these theorists, what matters to a bona fide democracy is a sustainable arrangement capable of aggregating diverse demands and finding workable compromises. Alfred Stepan (Reference Stepan1988: 6) maintains that liberalization is primarily about civil society but democratization is more about political society, which refers to party politics and election. Civil society affects how a democracy is consolidated, but the latter is primarily centred on the institutionalization of politics (Diamond Reference Diamond1994: 15). What is less examined is the parallel development of civil society and how it contributes to democratic consolidation. The rise of professional SMOs and their role in reducing protest violence is a clear case, and without such moderation, protests are not necessarily institutionalized in a new democracy. In addition, the early proponents of political transition theory appear too sanguine about the pro-democracy behaviour of elected politicians. We find opposition parties are frequent participants at the protest scene and their presence is significantly associated with an uptick in protest violence.

Our investigation highlights the importance of democratization in shaping the way people make protests. Democratization helps reduce protest violence, both directly and indirectly. The direct route exists because both protesters and regime incumbents know that resorting to force is likely counterproductive. Democratization encourages protesters to exercise self-restraint, evidenced by the rise of festive and performative tactics that aim to gain more public support rather than threaten the opponent. Democratization also fosters a friendlier environment for protest participation and inter-organization collaboration, both of which can reduce protest violence. Our findings support the observation that protest policing under democracy is ‘morally ambiguous’ since protesters are citizens, not criminals (Waddington Reference Waddington, della Porta and Reiter1998: 129).

Conclusion

Our inquiry responded to the research question of how democratization structures the dynamics of social protests. We chose a country that has undergone a smooth and successful political transition and sampled the reported rallies and demonstrations in front of the Presidential Office Building to see how protest violence and tactical choice evolved over three decades. Following a multivariate analysis of 421 protest events, we conclude that democratization has institutionalized protests contentiously. Social protests have become less violent, as protesters are more willing to adopt non-confrontational tactics. Democracy was capable of constraining the disruptiveness of social protests in the long run. However, violent and politicized conflicts remained an enduring possibility, even though their occurrence has become less frequent.

Protest-making, after all, makes up only one form of civic participation, especially for those who find themselves in a dire situation. We expect democracy to be more tolerant of protest activities and at the same time broaden the other venues of participation. According to John Dryzek (Reference Dryzek1996), democratization entails the political inclusion of defining concerns of civil-society groups into the state's core agenda without depleting their mobilizing capacity. Beside the institutionalization of protests, a democracy is expected to reinvent itself constantly by making information more accessible, policy-making more transparent and lowering the threshold of popular participation (Ho Reference Ho2022). In spite of these democratic innovations to incorporate more diversified forms of participation, protest-making remains a central component of political freedom and is often a last resort for the excluded minority.

Furthermore, democratically elected leaders also use repressive violence towards protests. Christian Davenport (Reference Davenport2007: 10–14) has persuasively questioned the so-called ‘domestic democratic peace’ assumption by highlighting the fact that a democracy can actually suppress protests ‘more legitimately’. Our findings stop short at uncritically endorsing the virtues of contemporary democracies. True, democracies can at times be as repressive as dictatorships when it comes to disruptive protests, but there remains a crucial difference in that democratic leaders are more likely to face the political responsibility of their repression decisions.

Our findings lend support to the institutionalization thesis, which contends that protests gravitate towards a more routinized and stable condition over the long haul. While this perspective was primarily anchored in research in the context of Western democracies, this article identified the causal paths of democratization by examining a case of recent political transition. The common emergence of a social movement society in both established and young democracies points to global convergence. Regardless of region, degree of economic development or pre-democratic trajectories, democracy exerted a consistent structuring power in patterning state–society interactions.

There are broader implications from our single-country observation for future research. Taiwan belongs to a subset of third-wave democratizing countries that underwent a smooth transition without a reversal. After an electoral defeat, the former authoritarian party has reinvented itself as a democratic contender that regained national power without causing a backslide into authoritarianism. Taiwan's experience provides a lens for understanding the long-term effect of democratization, which is definitely different from the observation of an incomplete transition to semi-democracy (Russia, for instance) or reversion to authoritarianism (Thailand and Burma). Among this fortunate subset, Taiwan shares many intimate similarities with South Korea. Both countries began the transition in the mid-1980s after an economic take-off and have undergone three peaceful changes of ruling parties. Studies on South Korea point to the abiding presence of social protests and their political impacts (Chang and Shin Reference Chang, Shin, Shin and Chang2011; Koo Reference Koo1993). In terms of protest symbolism, there is a clear transition from the firebombs of the 1980s to the more recent ‘candlelight vigils’ (Shin Reference Shin and Chiavacci2020). Aside from continuing street protests, movement activists also had the options of forming alternative parties or joining mainstream ones (Lee Reference Lee2022). The next step in research along this line needs to compare the more successfully democratized countries to test the generalizability of the contentious institutionalization thesis.

Finally, democracies, young and old, are facing a grim challenge in the face of the worldwide surge of populist leaders who harness voters' deep-seated grievances in their bids for national power. Once in power, they have proceeded to dismantle the rule of law, the separation of powers, freedom of speech and other institutional foundations of a working democracy (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Our research indicates that the involvement of politicians tends to increase the likelihood of protest violence – a built-in factor of uncertainty in democracy – begging the question, what happens if sitting populist leaders incite their supporters to protest action? The world-shocking riot at the United States Capitol on 6 January 2021 and the similar incident in Brasilia on 8 January 2023 clearly demonstrate the toxic mixture of populism and protest politics. Further observation is needed to see whether populism is going to undo the democratic institutionalization of protests.

Financial support

This research is funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), Taiwan (grant no. 108-2410-H-002-204-MY2).