1. Introduction

Chronic and recurrent conditions such as bipolar disorder (BD) show improved short- and long-term outcome when early detection and treatment is provided [Reference Benarous, Consoli, Milhiet and Cohen1–Reference Vieta, Berk, Schulze, Carvalho, Suppes and Calabrese3]. The identification of risk factors or prodromal symptoms may help defining at-risk stages before full-blown syndromic presentations with major clinical and treatment implications and, ideally allowing for early stage-specific, rather than disorder-specific, treatments [Reference Scott, Leboyer, Hickie, Berk, Kapczinski and Frank4, Reference Vieta, Salagre, Grande, Carvalho, Fernandes and Berk5].

Sleep abnormalities have been proposed as susceptibility markers in individuals at high risk of developing BD [Reference Ritter, Marx, Lewtschenko, Pfeiffer, Leopold and Bauer6, Reference Zanini, Castro, Cunha, Asevedo, Pan and Bittencourt7]. They are included as diagnostic criteria and almost invariably present during acute episodes [8]. Sleep abnormalities are frequently present as immediate or quasi-immediate prodromes of BD acute episodes [Reference Ng, Chung, FY-Y, Yeung, Yung and Lam9–Reference Young and Dulcis13].

Circadian abnormalities and sleep symptoms represent a cardinal feature during acute manic and depressive episodes, potentially serving as trait biomarkers of BD [8]. BD patients suffer from enduring biological rhythm abnormalities, even during remission phases [Reference Milhiet, Boudebesse, Bellivier, Drouot, Henry and Leboyer10, Reference Pinho, Sehmbi, Cudney, Kauer-Sant’anna, Magalhães and Reinares14]. Correlations between several sleep and circadian phenotypes, and the development of BD were demonstrated, providing clues to new approaches for both preventing and treating BD [Reference Milhiet, Boudebesse, Bellivier, Drouot, Henry and Leboyer10, Reference Pagani, St Clair, Teshiba, Service, Fears and Araya15].

Sleep alterations, might also precede the onset of BD by presenting as risk syndromes, detectable before the full-blown mood disorder, or as prodromes immediately preceding the first acute mood episode. Both as risk factors or immediate prodromes, detectable sleep alterations before first- or following affective episodes sahre implications for clinical research and practice [Reference Geoffroy and Scott16], but also for early diagnosing [Reference Kapczinski, Magalhães, Balanzá-Martinez, Dias, Frangou and Gama17]. Moreover, the possibility of objective measures of sleep alterations outlines their potential role as biomarkers, helping to redefine BD beyond a classical clinical definition [Reference Alda and Kapczinski18, Reference Carvalho, Köhler, Fernandes, Quevedo, Miskowiak and Brunoni19].

In recent years, a systematic review focused on a possible link between the onset of sleep problems and the subsequent development of BD [Reference Ritter, Marx, Bauer, Leopold, Lepold and Pfennig20], but its results were somewhat hampered by a relative scarcity of studies reporting prospective results.

Considering the growing evidence on this topic in later years, our aim was to perform and updated systematic review on the evidence on the possible role of sleep alterations anticipating the onset of BD. Secondarily, the aim of this review is to investigate the possible relationship between specific sleep alterations according to the polarity of the BD acute affective onset.

2. Methods

The present review has been conducted according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and PRISMA Group21]. Studies focused on sleep alterations preceding BD relapses/recurrences and studies including individuals at high risk for BD not meeting a standardized diagnosis were not considered in the present review.

2.1. Literature Review

A systematic search was performed using MEDLINE/PubMed/Index Medicus and the Cochrane Library, considering a time period ending on January 1st, 2018 A cross-check between references obtained was done. A further search in the site www.clinicaltrials.gov controlled for literature results and screened for eventually started, ongoing, or concluded but unpublished studies.

Studies included were: 1. Prospective studies on offspring of BD patients, later diagnosed with BD; 2. Prospective studies on patients with sleep problems developing BD; Retrospective studies on sleep problems in BD patients.

The full search strategy for the 3 types of studies included is presented in the S2.1 file

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Studies should report details on design, sample description, inclusion/exclusion criteria, defined aims, clear methodological procedures, clear outcome definitions or information about the diagnostic tools used for the assessments, and considering BD individuals diagnosed with DSM-IV-TR/DSM-IV/DSM-III [22–24] or ICD-10/ICD-9/ICD-8 [25–Reference World Health Organization27].

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

Original peer-reviewed articles published in English language.

2.2.2. Specific inclusion criteria for the 3 types of studies included in the present review

Prospective studies on offspring of BD patients:

1. Cohort studies on high-risk individuals (i.e. offspring or unaffected first-degree relatives of individuals with BD, and had assessed sleep alterations with/without circadian alterations at baseline, and conversion to full-blown BD at follow-up.

Prospective studies on patients with sleep problems developing BD:

2. Cohort studies on individuals with sleep alterations with/without circadian alterations and psychopathology assessment at baseline, and the development of full-blown BD at follow-up.

Retrospective studies on BD patients:

3. Cohort studies on individuals with a diagnosis of BD or a first episode of psychosis later diagnosed with BD, studying sleep alterations with/without circadian alterations at baseline (working definitions for this condition vary, but studies in which a specific definition was included were considered for inclusion). Study sample size of at least 30 individuales. These studies should then report specific data on conversion to full-blown BD at follow-up.

Sleep alterations could be assessed via either questionnaire or through actigraphy or polysomnography or other specific sleep-related exams.

Results on sleep alterations in BD patients with depressive or psychotic onset were considered for inclusion when a further, subsequent conversion to a BD diagnosis was established with standard assessments.

2.2.3. Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: 1. animal studies; 2. Studies including general or psychiatric populations not specifying the number of BD individuals; 3. Studies not specifying a standardized BD diagnosis (criteria DSM or ICD) at baseline and/or follow-up; 4. Studies with no specific sleep assessment; 5. Reviews or meta-analyses or studies with N < 10. 6. Studies focused on sleep alterations preceding BD relapses/recurrences. 7. Studies including individuals at high risk for BD who did not meet a standardized diagnosis.

2.3. Data collection process and items

Data were classified into three groups: 1. data of interest, 2. duplicated data, and 3. data of no interest, according to the previously described criteria. Studies concerning molecular and genetic aspects, as well as those assessing or comparing efficacy of medications, were not included.

After first exclusion, full studies were retrieved and examined. References were also reviewed to identify further possible studies of interest.

2.3.1. Data extraction

The titles and/or abstracts of studies were screened independently (CP and NV) to identify studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria outlined above. After elimination of duplicated sources, the full texts of these potentially eligible studies were retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility by CP and NV. Any disagreement over the eligibility of particular studies was resolved through consensus or, when agreement was not achieved, through discussion with AM. A standardized, excel form was used to extract data from the included studies for the assessment of study quality and for evidence synthesis. Where possible, time between first sleep symptoms and onset of BD was extracted and presented along with other results.

2.3.2. Methodological quality assessment

Two independent authors (CP and NV) evaluated the risk of bias for each domain described in the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) which was developed to assess the quality of non-randomized case-control and cohort studies with its design, content and ease of use directed to the task of incorporating the quality assessments in the interpretation of meta-analytic results [Reference Zeng, Zhang, Kwong, Zhang, Li and Sun28]. For cross-sectional studies, a previously adapted version of the NOS was used [Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil29]. Discrepancies between the two raters were solved by consensus among three researchers (CP, NV, AM).

3. Results

3.1. Systematic search results

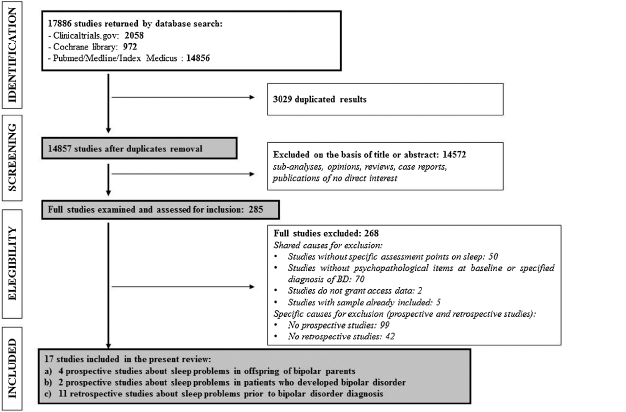

The whole search returned 17,886 papers. After duplicate removal, 14,572 papers were excluded on the basis of title or abstract because of no direct interest. The remaining 285 studies were examined and assessed for inclusion, of them 268 were excluded for different reasons (Shared causes: Studies without specific assessment points on sleep: 50; Studies without psychopathological items at baseline or specified diagnosis of BD: 70; Studies do not grant access data: 2; Studies with sample already included: 5. Specific causes (prospective and retrospective studies): No prospective studies, respectively: 99; No retrospective studies: 42). Finally, 17 studies were included in the present review (Fig. 1).

3.2. Contents results

3.2.1. BD offspring prospective studies

A total of 4 studies were included in this part of the review (Table 1).

The CARE (Children and Adolescent Research Evaluation) study is a prospective follow-up cohort on healthy Amish started in 1994, and aimed at detecting possible prodromal features for BD [Reference Egeland, Endicott, Hostetter, Allen, Pauls and Shaw30] After 16 years of follow-up, 9 children met full criteria for BD type I, 8 originally from the BD parent sample, 1 from the control sample. At the last follow-up 50% of children later diagnosed with BD presented decreased sleep as an antecedent.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart of studies selection for the systematic review.

Table 1 Prospective studies of offspring with parents with Bipolar Disorder.

Table 2 Prospective studies with patients with sleep disorders/symptoms who develop Bipolar Disorder.

Table 3 Retrospective studies considering a history of sleep disorders/symptoms in BD patients.

A Canadian prospective study began in 1998 with the aim to describe the possible onset of psychiatric disorders in siblings of BD parents [Reference Duffy, Horrocks, Doucette, Keown-Stoneman and McCloskey31]. BD diagnosis was met by 31 subjects, all from the high-risk offspring. The high-risk offspring had a higher lifetime risk of sleep disorders (HR = 28.21, P = 0.02), compared with control offspring. Anxiety/sleep disorders started about 6 years before the onset of first major mood episode (p = 0.008).

In the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study (BIOS) [Reference Levenson, Soehner, Rooks, Goldstein, Diler and Merranko32], BD parents and healthy comparison parents were recruited. All offspring of 6–18 years of age were included. Offspring of BD parents (“at-risk”). A sample of 612 (335 BD and 277 non-BD) offspring were assessed until age 18. At the final 8th-year endpoint, 25/227 high-risk offspring developed BD. Three latent sleep groups were characterized (good sleepers, poor sleepers and variable sleepers) based on the likelihood of sleep. After controlling for confounding factors, the poor sleep group had a 4-fold odds of developing BD than those in the good sleep group (OR = 4.25), though results remained marginally non-significant. High “weekend-to-weekdays variability” sleep patterns (variable group) had low likelihood of developing BD. Sleep symptoms presented about 3 years before BD onset.

The Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study [Reference Mesman, Nolen, Keijsers and Hillegers33] aimed to identify early signs of mood disorders, specifically BD in adolescent BD offspring. At baseline, 27% of the offsprings had a history of any mood disorder and 73% had no mood diagnosis (“No MD”). After 12 years, 10/29 (34%) from the ‘Any MD’ group converted to BD with an (hypo)manic onset. In this group, decreased need of sleep (50% vs 5%, p = 0.011) and middle insomnia (40% vs 5%, p = 0.036) were significantly associated with BD conversion. The median time to (hypo)mania onset after the baseline assessment was 2.7 years.

3.2.2. Prospective studies on sleep disorders patients

A total of 2 studies were included in this part of the review (Table 2).

The risk of psychiatric disorders over a 6 years follow-up period was evaluated in a large cohort study including adult subjects [Reference Chung, Li, Kuo, Sithole, Liu and Chung34]. Patients with insomnia treated with hypnotic drugs had a higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders, especially BD, compared to those with insomnia not on hypnotics and people without insomnia too (HR: 7.60; 95% CI: 5.31–10.89 and HR: 14.69; 95% CI: 11.11–19.43).

The first study to assess longitudinally a possible association between disturbed sleep in healthy individuals and the subsequent onset of BD was conducted on a large cohort [Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig35]. Among the 1943 patients included, 41 (1.8%) developed BD at follow-up (mean age at onset 17.2 ± 4.8 years). Disturbed sleep in participants without a major mental disorder at T0 conferred an increased risk for BD onset (OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.25–2.45; p = 0.001), even when adjusted for age, sex, parental mood disorder and lifetime cannabis or alcohol dependence. Even among participants without a positive family history of mood disorders (N = 1430) insomnia was significantly associated with BD (OR = 1.80; p = 0.003). When evaluating each sleep symptom, “trouble falling asleep” (OR = 1.51; p = 0.006) and “early morning awakening” (OR = 1.38; p = 0.048) showed significant odds of predicting BD. Survival analyses indicated that an increased risk over the 10 years follow-up with and a mean duration between T0 assessment and conversion to BD of 1.9 years.

3.2.3. Retrospective studies on BD patients

A total of 11 studies were included in this part of the review (Table 3).

In the aforementioned Amish study, psychopathological features of parent patients prior to BDdiagnosis were asked to recall prodromal symptopms [Reference Egeland, Hostetter, Pauls and Sussex36]. Sleep problems appeared as the fourth most common symptoms reported between age 13 and 15 (23%), detectable during childhood at least 9–12 years prior to BD onset.

Another study evaluated 82 pediatric BD patients [Reference Faedda, Baldessarini, Glovinsky and Austin37]. About 7 years of delay were found until BD diagnosis/treatment (symptomatic onset occurred before age 3 in 74% of cases, and before age 13 in 95%).

Potential temporal and symptomatic differences between the prodrome to psychotic vs. nonpsychotic manic onsets were assessed in a study including a sample of 52 BD children and adolescents [Reference Correll, Penzner, Frederickson, Richter, Auther and Smith38]. Non significant differences in prevalence in psychotic mania vs. non psychotic mania for: “decreased need for sleep” (respectively 41.2% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.58) and “insomnia” (41.2% vs. 27.8%, p = 0.34). Both groups presented a prevalent “insidious” pattern of onset of prodromal symptoms (1.7 ± 1.8 years before psychotic mania, 1.9 ± 1.5 years before nonpsychotic mania, 2.3 ± 2.1 before depressiion).

A comparison between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD, n = 29), BD (n = 25) and healthy controls (n = 28) aimed at investigating possible prodromal symptoms to these conditions in adolescents [Reference Rucklidge39]. Among BD patients, 60% had difficulties getting to sleep and 32% presented a decreased need for sleep in adolescence compared respectively to 65.5% and 24.1% (ADHD group) and 28.6% and 3.6% (control group) with no statistical significance. “Frequent awakenings at night” was present in 44% of BD patients and 7.1% of the control group (p < 0.01).

The course of individual symptoms over the first 10 years of life in juvenile-onset BD and ADHD, alone or comorbid, was compared with healthy controls [Reference Luckenbaugh, Findling, Leverich, Pizzarello and Post40]. “Decreased sleep” was present in 44% of the BD, 9% of the ADHD, 8% of controls, and significantly higher in BD vs. ADHD (p = 0.0005) and VD vs. controls (p = nr).

Another study examined symptoms and prodromes 1 year before a psychotic manic onset [Reference Conus, Ward, Lucas, Cotton, Yung and Berk41]. Clinical symptoms were common in 11/22 (50%) participants. Among them, “disrupted sleep” was present in 83.3% of the sample, “reduced sleep or need for sleep” in 61.1%. The mean duration of sleep symptoms was 20.9 ± 16.4 weeks.

In a Norwegian study, prodromal symptoms and behaviours of 15 BD type II patients were explored [Reference Skjelstad, Holte and Malt42]. Prodromal symptoms were divided into 3 groups according to whether life events at the time of the symptom elicited an appropriate or exaggerated reaction: group A, with symptoms linked to normal responses to environment stimuli, group B, with symptoms characterized as “exaggerated” in relation to environment stimuli, group C, with symptoms characterized as inexplicable or unrelated to the context or to environment stimuli. Symptoms of B and C criteria. Overall, 5/15 patients experimented sleep disturbances. No patients with sleep disturbances met the B or C criteria. Sleep symptoms started about 11 years before BD.

The course of pre-(hypo)manic and pre-depressed prodromal symptoms was assessed in a study on 44 BD type I or II patients [Reference Zeschel, Correll, Haussleiter, Krüger-Özgürdal, Leopold and Pfennig43]. “Reduced sleep requirement” was present 1.3 ± 1.9 months prior to illness onset in 71.4% of the pre-(hypo)manic patients and none of the pre-depressed. “Insomnia” was present 1.4 ± 2.0 months before in 54.8% of the pre-(hypo)manic patients and in 66.7% of the pre-depressed (3.9 ± 6.9 months). “Hypersomnia” was present 1.0 ± 1.1 months prior in 7.1% of the pre-(hypo)manic patients and 6.0 ± 9.7 months before in 33.3% of the pre-depressed.

One of the studies proceeding from the McLean-Harvard First Episode Project investigated possible differences in pre-onset symptoms between purely psychotic- (23.5%), and manic psychotic- (18.1%) and depressive psychotic (58.4%) onset (76.5%) patients in 263 BDI patients with at least one lifetime psychotic episode, [Reference Salvatore, Baldessarini, H-MK, Vázquez, Perez and Faedda44]. “Sleep disturbances” were present in 1.3% of the psychotic manic-onset group and absent in the others (p = ns) Age at first sleep problem was 18.0 ± 0.0 years, about 16.5 years before the onset of the first psychotic episode.

A recent study aimed to retrospectively examine the prevalence, coexistence and persistence of sleep disturbances across the course of BD [Reference Kanady, Soehnera and Harvey45]. Sleep disturbances (i.e. insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced need for sleep, delayed sleep phase and irregular sleep patterns) preceded the onset of illness of about 3 years (age at onset of sleep disturbance: 18.3 ± 9.7).

The prodromes of BD (hypo)manic vs. depressive onset were studied on a sample of 43 stable BD type I (74.4%) and II (25.6%) outpatients [Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46]. Prior to (hypo)manic onset, “insomnia” was present in 48.8%, “decreased need of sleep” in 25.6%, the “inversion of the sleep/wakefulness pattern” in 14% and hypersomnia in 7%. Prior to depressive onset, “insomnia” and “hypersomnia” were both present in 14% of BD subjects, “decreased need for sleep” and “inversion of sleep/wakefulness pattern” both in 4.6%. Sleep problems were more frequent prior to (hypo)manic onset than to depressive onset, independently of BD subtype.

The quality assessment of the studies included in this systematic review outlines a wide heterogeneity in studies design, populations and outcomes (See Suppl. Table 1). Among the cohort studies, 2 groups showed true representativeness. All cohort studies showed adequate case definition groups of interest appropriate evaluation of outcomes and good follow-up. The quality evaluation of case-control studies returned lower quality in representativeness, sample size and comparability, and – by definition- lower quality in outcome recollection, limited by self-report.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed at understanding the clinical relationship between sleep problems and the onset of BD, updating the work by Ritter and cols. (2011).

In the last years several new studies focused specifically on this topic, 4 reporting results on prospective follow-ups [Reference Levenson, Soehner, Rooks, Goldstein, Diler and Merranko32–Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig35], whilst 11 presenting retrospective design. The onset of sleep problems in people who subsequently developed BD may long anticipate a full-blown BD, occurring during adolescence or pre-adolescence [Reference Benarous, Consoli, Milhiet and Cohen1, Reference Ritter, Marx, Bauer, Leopold, Lepold and Pfennig20, Reference Duffy, Horrocks, Doucette, Keown-Stoneman and McCloskey31]. These alterations may be pointed out with subjective and objective (i.e. actigraphic) measures also in populations at high-risk for BD, but never diagnosed [Reference Melo, Garcia, Linhares Neto, Sá and de Araújo47]. Sleep and chronotype alteration patterns are similar to those found in full-blown BD patients when compared to healthy controls [Reference De Crescenzo, Economou, Sharpley, Gormez and Quested48], so that their accuracy in predicting a conversion to full-blown BD has to be ascertained.

Globally, sleep problems seem more frequent in the offspring of patients with BD (high-risk offspring) compared to children of healthy controls [Reference Sebela, Novak, Kemlink and Goetz49], with a surprising 30-fold increased risk to develop sleep disorders compared to not-at-risk offspring [Reference Duffy, Horrocks, Doucette, Keown-Stoneman and McCloskey31]. Despite the clear association, no threshold on sleep alterations patterns has been outlined. Also, high-risk offspring present weak and more unstable rest-activity cycles, as indicated with actigraphy by lower relative amplitude and higher variability in sleep efficiency in comparison with controls [Reference Ng, Chung, FY-Y, Yeung, Yung and Lam9]. Unfortunately, clinical applicability of these findings is doubtful.

When taking into consideration the lapse between sleep disturbances and BD onset, prospective studies almost invariantly agree on the development of generic sleep problems more than 1 year before BD (1.9–6 years [Reference Duffy, Alda, Hajek, Sherry and Grof50, Reference Levenson, Soehner, Rooks, Goldstein, Diler and Merranko32, Reference Mesman, Nolen, Keijsers and Hillegers33, Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig35]. Interestingly, the retrospective studies reviewed present a longer latency, more than 1 year before BD onset (adolescence or pre-adolescence) [Reference Faedda, Baldessarini, Glovinsky and Austin37, Reference Correll, Penzner, Frederickson, Richter, Auther and Smith38, Reference Skjelstad, Holte and Malt42, Reference Salvatore, Baldessarini, H-MK, Vázquez, Perez and Faedda44] compared to few months in young adulthood onset [Reference Conus, Ward, Lucas, Cotton, Yung and Berk41, Reference Zeschel, Correll, Haussleiter, Krüger-Özgürdal, Leopold and Pfennig43, Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46]. An overestimation of sleep problems is possible. Also, generalizability from child-adolescent BD to adult BD populations may be hampered by the lack lack of consensus over the very consistence of BD diagnosis in childhood/adolescence [Reference Carlson and Meyer51, Reference Douglas and Scott52].

4.1. Sleep prodromes and polarity of onset

4.1.1. Decreased need for sleep

A common finding throughout the present review is that decreased sleep may be present time before BD onset in a variable percentage of patients ranging from 24% to 44% in retrospective studies [Reference Egeland, Hostetter, Pauls and Sussex36, Reference Rucklidge39, Reference Luckenbaugh, Findling, Leverich, Pizzarello and Post40], and up to 50% in a prospective study [Reference Egeland, Endicott, Hostetter, Allen, Pauls and Shaw30]. This seems an aspecific finding, as, for instance, a generic decrease in sleep also is reported for individuals at risk for psychosis with no significant differences compared to individuals at risk for BD [Reference Zanini, Castro, Cunha, Asevedo, Pan and Bittencourt7]. Undoubtley a close monitoring of individuals at risk for developing both conditions is due anyway, and the treatment of common psychopathologica prodromes could be tried as suggested by recent transdiagnostic staging models [Reference Scott, Leboyer, Hickie, Berk, Kapczinski and Frank4]. Predictably, manic and hypomanic BD onset episodes are mostly associated with a decreased need for sleep, appearing in 25.6% up to 71.4% of pre-manic patients [Reference Zeschel, Correll, Haussleiter, Krüger-Özgürdal, Leopold and Pfennig43, Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46] and it may precede BD manic onset by about 1–8 months. According to the results of this review, prolonged decreased need for sleep represents a good prodrome to a manic onset.

4.1.2. Insomnia

Insomnia seems an important prodrome of BD in 2 prospective studies, with an HR of 14.69 in one study [Reference Chung, Li, Kuo, Sithole, Liu and Chung34], and with an OR of 1.51 (for initial insomnia) and 1.38 (for late insomnia) in the other [Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig35]. Also retrospective studies seem consistent with its predictive value. Insomnia seems the most frequent symptom prior to depressive onset (14.0%–66.7%), and appearing 7.3 to 3.9 months before the episode [Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig35, Reference Zeschel, Correll, Haussleiter, Krüger-Özgürdal, Leopold and Pfennig43, Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46]. Insomnia also precede manic onset (48.8%–54.8%) from 1.9 months up to 1.9 ± 1.5 years [Reference Correll, Penzner, Frederickson, Richter, Auther and Smith38, Reference Zeschel, Correll, Haussleiter, Krüger-Özgürdal, Leopold and Pfennig43, Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46]. Again, insomnia is very unspecific, also commonprior to unipolar depression [Reference Ritter, Marx, Bauer, Leopold, Lepold and Pfennig20, Reference Baglioni, Battagliese, Feige, Spiegelhalder, Nissen and Voderholzer53, Reference Correll, Penzner, Frederickson, Richter, Auther and Smith54]. Despite its aspecific nature, insomnia allows identification of populations at high risk for serious mental conditions such as BD, depression or schizophrenia.

4.1.3. Hypersomnia

Although less frequent, hypersomnia seems more specific of a depressive BD onset. It precedes the onset of the disease of 6–7 months [Reference Zeschel, Correll, Haussleiter, Krüger-Özgürdal, Leopold and Pfennig43, Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46], its frequency ranging from 14% up to 33.3%, compared with pre-manic patients (about 7%). Hypersomnia was associated with the onset of a bipolar depression episode [Reference Kaplan, Gruber, Eidelman, Talbot and Harvey55] and may also differentiate bipolar depression (in BD type II patients) from unipolar depression, with a positive predictive value of around 70% [Reference Hantouche and Akiskal56]. Interestingly, hypersomnia is also a clinical symtptom present in the “atypical features” diagnostic specifier. This underlines its possible direct and indirect relation with a bipolar diathesis in major depression that is being investigated [Reference Petri, Bacci, Barbuti, Pacchiarotti, Azorin and Angst57]. Despite a careful and critical assessment of hypersomnia is due [Reference Dauvilliers, Lopez, Ohayon and Bayard58], our results suggest that hypersomnia is a potential prodrome of bipolar depressive onset.

4.1.4. Circadian rhythm alterations

In this review scant data concerning alterations in circadian rhythms were returned. A lower likelihood of conversion for the “extreme evening type” pattern of circadian rhythm (i.e. defined as an eveningness circadian preference <10th percentile of the entire sample) in youth at genetic risk for BD was reported in one study [Reference Levenson, Axelson, Merranko, Angulo, Goldstein and Mullin59]. This contrasts with previous evidence, as BD in adolescent and adult BD patients seems significantly associated with significantly higher prevalence of “evening types” than healthy controls [Reference Milhiet, Boudebesse, Bellivier, Drouot, Henry and Leboyer10, Reference Wood, Birmaher, Axelson, Ehmann, Kalas and Monk60, Reference Kim, Weissman, Puzia, Cushman, Seymour and Wegbreit61]. However, it circadian preference tends to differ between childhood and adolescence and a substantial shift to an evening circadian preference is observed at around 12–13 years of age [Reference Gau and Soong62, Reference Tonetti, Adan, Di Milia, Randler and Natale63]. Considering that the mean age in the study by Levenson and cols. was 11 ± 3.6 years, it is possible that a switch to an evening chronotype was missed. Also, the association of evening chronotype and BD could be independent or partially mediated by chronic sleep deprivation due to social needs (e.g. early awakening) triggering a mood episode [Reference Melo, Abreu, Linhares Neto, de Bruin and de Bruin64]. One included study reports a generic “inversion of the sleep/wakefulness pattern”. This is not frequent in either pre-depressive and pre-manic patients, but when present it might anticipate full illness-onset more than one year. [Reference Noto, Noto, Caribé, Miranda-Scippa, Nunes and Chaves46]. Newest resultsfrom the BIOS cohort [Reference Levenson, Soehner, Rooks, Goldstein, Diler and Merranko32] show that weekend-to-weekday sleep variability were not substantially associated with elevated risk of developing BD among at-risk youth.

To a varying degree, results in this systematic review point to somewhat aspecific sleep and biological rhythm disturbances. Despite this, their appearance in at-risk populations and their high prevalence anticipating acute episodes [Reference Jackson, Cavanagh and Scott65, Reference Rosa, Comes, Torrent, Solè, Reinares and Pachiarotti66], calls for specific and timely interventions. This is especially true when considering that sleep alterations are potentially amenable to pharmacological and psychological treatment [Reference Joslyn, Hawes, Hunt and Mitchell67]. To avoid overmedication of these individuals, psychological and psychoeducational interventions should be especially considered to achieve improved illness outcomes [Reference Oud, Mayo-Wilson, Braidwood, Schulte, Jones and Morriss68–Reference Vieta, Salagre, Grande, Carvalho, Fernandes and Berk70].

5. Limitations

The present systematic review was conducted considering only studies in English language. Although this potentially limits the generalizability of results in terms of geographic and ethnical differences, most international peer-review journals publish studies written in English language

We also chose to include data on diagnosed BD patients. This is likely to have cut out most of the evidence on sleep biomarkers and translational research performed on high-risk individuals. On the other hand, the excluded evidence could point to populations at risk and be not associated with a full-blown BD condition, and this could be especially true for child/adolescent BD populations due to diagnostic consistency in such populations.

Also, studies focused on specific subpopulations such as BD type II or rapid cycling BD are lacking

The predictive value of sleep disturbances seems somewhat hampered by the scarcity of prospective studies on the topic and the heterogeneity of assessment measures used. Retrospective studies present data with possible recollection bias

6. Conclusions

Sleep prodromes seem good potential indicators for the early detection in those at highest risk of developing bipolar disorder. Their increased prevalence may be detected more than 1 year prior to the onset of the first affective episode. Despite sleep prodromes overall lack specificity for BD, especially in a pure clinical setting, hypersomnia might have a possible role in discriminating bipolar versus unipolar depression, and reduced need for sleep be a useful indicator for a manic onset. Early recognition and early specific intervention on sleep disturbance allow for a most effective management, but might also allow postpone illness onsetduring crucial periods of life such as adolescence and young adulthood.

Sleep and chronotype research still need more objective quantitative and qualitative approaches such as actigraphy and polysomnography evaluations or neuroendocrine assessment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D+I and co-financed by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the CIBERSAM (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017_SGR_1365) and the CERCA Programme / Generalitat de Catalunya.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.02.003.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.