A Cochrane review Reference Essali and Ali1 has concluded that there is no good randomised clinical trial evidence on which to base treatment guidelines for patients with very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (VLOSLP), Reference Howard, Rabins, Seeman and Jeste2 yet open treatment with atypical antipsychotics has been associated with improvements in symptoms at least as good as those seen in younger patients with schizophrenia or patients with early-onset schizophrenia who have grown old, Reference Barak, Aizenberg, Mirecki, Mazeh and Achiron3–Reference Scott, Greenwald, Kramer and Shuwall5 and antipsychotic treatment is the cornerstone of care pathways. Little is known about how many patients seen within specialist mental health services are engaged by those services and given antipsychotic treatment. To address this, we conducted a retrospective electronic patient record search.

Method

Participants

We used the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) system, developed within the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, to extract the records of all patients aged 60 years and above with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizotypal and/or delusional disorders (ICD-10 F20–F29) 6 in contact with services between 1 January 2007 and 21 August 2014. All identified patients' notes were reviewed and those who scored 24 or less on the standardised mini-mental state examination Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh7 or had a concurrent diagnosis of an organic mental disorder (ICD-10 F00–F09) 6 were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included any evidence that psychosis onset had been before the age of 60, insufficient recorded information to confirm diagnosis and less than 1 year of follow-up completed at time of CRIS search.

Events

The first face-to-face contact of mental health services with a patient was regarded as the start point of each service episode. Records were reviewed at 3 months to assess initial engagement with services. If a patient was discharged before 3 months, the last documented episode was used as an alternative. Two further engagement points, at 6 months and 12 months, were also examined. The length of each episode was also extracted and the level of engagement at the point of discharge from services was assessed.

Ethics approval for CRIS was given by the National Research Ethics Service Oxford REC C.

Results

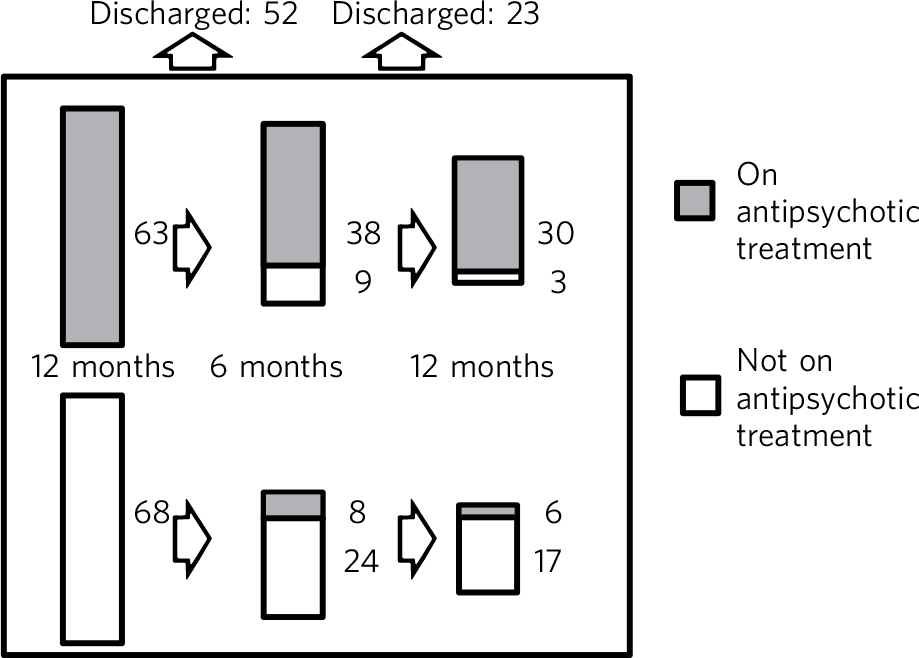

Search of the CRIS system initially identified 635 patients. Following inspection of the individual records, patients were excluded because of incorrect coding (n = 45), cognitive impairment (n = 216), onset of psychosis before age 60 years (n = 150), insufficient information to confirm diagnosis (n = 32) or in contact with services for less than 12 months preceding the search date (n = 61). Of the remaining 131 patients, 84 (64.1%) were female, 40 (30.5%) were White British, and 35 (26.7%) were living with a partner or family member. The extent of engagement with services and antipsychotic treatment at 3, 6 and 12 months is shown in Fig. 1. At the point of discharge from specialist services back to primary care, 65 patients (54%) had been lost to follow-up or had not engaged with specialist services, 22 (18%) had engaged with services but were not receiving antipsychotic treatment, and 33 (28%) were taking antipsychotic treatment. The rest were still receiving active specialist service follow-up. Twenty-six (19.8%) patients were treated compulsorily under a section of the Mental Health Act 1983, and neither male gender (odds ratio (OR) 1.15: 95% CI 0.47–2.80) nor membership of a Black or minority ethnic group (OR = 1.25: 95% CI 0.52–3.02) significantly influenced Mental Health Act use.

Fig. 1 Service and antipsychotic treatment engagement over 12 months.

Discussion

The diagnostic concept of VLOSLP emerged from an international consensus meeting held to advance research on a patient group with first onset of delusions and/or hallucinations after the age of 60 years, in the absence of affective disorder or demonstrable brain disease such as dementia. Reference Howard, Rabins, Seeman and Jeste2 The illness is viewed as a functional psychosis with symptoms that will respond to antipsychotic drugs. Reference Howard, Rabins, Seeman and Jeste2–Reference Scott, Greenwald, Kramer and Shuwall5 Our data show that less than half of patients with VLOSLP were commenced on antipsychotic treatment and less than a third remained on treatment at 1 year or at the point of discharge from services. This is a surprising, even disappointing, result. An important barrier to acceptance of antipsychotic treatment by patients with VLOSLP is the low level of insight into presence of mental health difficulties or need for treatment. Reference Howard, Almeida and Levy8 Although treatment-related decision-making capacity has not been specifically investigated in VLOSLP, studies of middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia have suggested that cognitive test scores, rather than psychopathology ratings, associate most strongly with the understanding and reasoning components of capacity. Reference Palmer, Dunn, Appelbaum and Jeste9 Patients with VLOSLP do not, however, have demonstrably abnormal brain imaging Reference Hahn, Kim and Lee10 and do not inevitably progress to develop dementia, Reference Palmer, Bondi, Twamley, Thal, Golshan and Jeste11,Reference Mazeh, Zemishiani, Aizenberg and Barak12 so cognitive impairment is unlikely to explain their inability to evaluate their illness or the need for treatment. Reluctance by clinicians to use mental health law to deliver compulsory treatment when patients will not accept the case for antipsychotic treatment is indicated by the small percentage of cases where this happened. Although there are limited studies to compare this with, it is in keeping with the lower rates of patients on longer-term detention within the above-65 population. Reference Thompson13 This may reflect a view that elderly patients with psychosis are somehow less ‘risky’ and that a failure to enforce treatment is therefore justifiable. In fact, untreated symptoms of VLOSLP are frightening and disabling, lead patients to place themselves at significant risk and damage relationships with family and neighbours. Comparably low levels of psychosis treatment in younger people would be completely unacceptable and specialist mental health services for older people should actively consider whether they should be more assertive in taking potentially effective treatment to this vulnerable patient group.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.