Stroke is recognised as a major cause of mortality and disability worldwide, leading to a high economic cost in the treatment period, especially in poor prognosis(1). Clinical data have shown that the nutritional status is poor in patients with stroke during the few weeks following acute onset, and the malnutrition risk was likely to be a crucial factor associated with poor prognostic outcomes(Reference Hsieh, Hung and Chang2,Reference Zhang, Zhao and Wang3) because it may allow the prediction of treatment tolerability and functional progression(Reference Barret, Malka and Aparicio4). Given that the malnutrition condition is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis that caused an increase in length of the average hospital stay, poor prognosis after discharge and disability-related hospital costs(Reference Reber, Strahm and Bally5,Reference Marco, Sanchez-Rodriguez and Davalos-Yerovi6) , nutritional screening tools are necessary to identify the stroke patients at a nutritional risk for developing an opportune nutrition care or medical support.

European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines for clinical nutrition in neurology suggests that the risk of malnutrition should be evaluated in stroke patients within 48 h of admission to identify prognostic factors for tailored treatments(Reference Burgos, Breton and Cereda7). Several quantitative tools with scoring scales have been developed to assess nutritional risk, postoperative complications and long-term outcomes, such as the prognostic nutritional index and Nutritional Risk Screening index (NRS-2002)(Reference Xiang, Chen and Ye8,Reference Wang, Luo and Xie9) . NRS-2002, as a standard method to assess nutritional risk, has been validated and conducted in hundreds of reported studies(Reference Çoban10,Reference Sahli, Hagenbuch and Ballmer11) . Controlling nutritional status (CONUT) is a newly proposed screening tool for assessing nutritional status and has been validated in several clinical settings(Reference Gon, Kabata and Kawano12,Reference Kheirouri and Alizadeh13) . It can be calculated from two biochemical parameters (serum albumin and cholesterol levels) and one immune indicator (total lymphocyte counts)(Reference Martineau, Bauer and Isenring14), which are representative markers of protein reserves, calorie deficiency, and impaired immune defenses, respectively. Moreover, the findings from a clinical study confirmed that CONUT’s concurrent validity (cut-off value: 4, sensitivity: 42 %, and specificity: 69 %) against ESPEN 2015 criteria in oesophageal cancer patients(Reference Wang, Chen and Liu15), and the high sensitivity and specificity in predicting disease prognosis have been described in previous studies (cut-off value: 3·5, sensitivity: 72·1–78·8 % and specificity: 50·7–83·5 %)(Reference Wang, He and Kang16,Reference Dong, Tang and Liu17) . Compared with the previous screening tools, the CONUT is more easily calculated from the data in blood measurements and is a newly proposed scoring system that allows for comprehensive assessment of patients in hospital settings.

Although previous studies have investigated the prognostic usefulness of the CONUT in determining the survival in patients with gastric cancer, malignant pleural mesothelioma and colorectal cancer undergoing gastrostomy(Reference Suzuki, Kanaji and Yamamoto18–Reference Yang, Wei and Wang20), clinical data using the CONUT score to predict stroke prognosis are scarce. Recent studies, including our group’s clinical epidemiological investigations, showed that the CONUT score was associated with a poor prognosis and high all-cause mortality in acute ischaemic stroke(Reference Naito, Nezu and Hosomi21,Reference Cai, Wu and Chen22) . Nevertheless, it is currently unclear whether the CONUT scores were effective in determining the 3-month functional prognosis in haemorrhagic stroke (AHS). The purpose of the current study was primarily to investigate the usefulness of the CONUT score for predicting a 3-month AHS prognosis and secondarily to compare the prognostic accuracy of CONUT with the corresponding accuracies of NRS-2002.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a multi-centre, prospective hospital-based epidemiological study. Patients who had neuroimaging-confirmed acute haemorrhagic stroke and were admitted to the hospital within 1 week after the sudden onset were enrolled in five major hospitals in Wenzhou regions of Zhejiang province, China, including the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Ruian People’s Hospital, Yueqing People’s Hospital, Yongjia People’s Hospital and Pingyang People’s Hospital. All the patients provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (No. 2016209).

Study participants

A total of 349 patients with a medical diagnosis of AHS were consecutively enrolled from October to November in 2018. Of those, twenty-one patients were excluded because they missed a 3-month morbid assessment using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Clinical data were collected by the same professionally trained investigator. The following data were collected: demographic variables (age, gender and BMI), stroke-related comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation and CHD), clinical assessments (The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score and Barthel Index) and laboratory biochemical parameters (serum albumin, total lymphocytes and total cholesterol). The demographic variables including BMI, stroke-related comorbidities, clinical assessments and laboratory biochemical parameters were assessed within 48 h after admission. Outcome measurements were assessed at two time points: within 48 h post discharge (length of hospital stay, hospitalisation costs, nutrition support and infectious complications) and 3 months post discharge (mRS and all-cause mortality). The NIHSS was used to evaluate the stroke severity on admission. The Barthel Index was used for the evaluation of activities of daily living (ADL). At the end of the 3 months and after discharge, the data on the follow-up measures were collected by phone.

Controlling Nutritional Status score and Nutritional Risk Screening index-2002

We used the CONUT score and the NRS-2002 for nutritional risk assessments. The CONUT score was calculated from the levels of three laboratory parameters including serum albumin, lymphocytes and total cholesterol(Reference Martineau, Bauer and Isenring14). We set 2 as the cut-off value for CONUT score by a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves analysis (online Supplementary Fig. S1) and categorised the patients into low-CONUT and high-CONUT groups according to the CONUT score: no or low risk of malnutrition (0–1) and high malnutrition risk (2–12). The NRS-2002 score of ≥ 3 points indicates that the patient is at nutritional risk(Reference Kondrup, Rasmussen and Hamberg23), considering the impaired nutritional status, the severity of the disease and the patients’ age. Screening details on the CONUT and NRS-2002 scores were summarised in Supplementary Table S1 & Table S2, respectively.

BMI was calculated from the preoperative heights and weights of the study individuals, which were measured by our medical staff within a few hours after admission to the hospital. The cut-off value of BMI < 18·5 kg/m2 was defined as malnutrition risks according to the WHO standard(24).

Outcome measurements

The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) was applied to assess the degree of disability in stroke patients, and the primary outcome was a poor functional prognosis with a mRS score of 3–6 at 3-month discharge(Reference Kim, Lee and Kim25). The secondary outcomes were an all-cause mortality at the 3-month post discharge mark, length of hospital stay, the ability at hospital discharge (evaluated by NIHSS score), ADL at hospital discharge (assessed by Barthel Index), hospitalisation costs, nutritional support and rates of complications during hospitalisation.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as percentages for categorical variables and median (interquartile range, IQR) or mean (standard deviation, sd) for continuous variables according to their normal distributions, which were evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. When comparing the difference in baseline and follow-up outcomes between high-CONUT and low-CONUT groups, a t test analysis was performed for the continuous normal-distribution data and the Mann–Whitney U test for the non-normal data, while the χ 2 test was used for categorical variables. To analyse the impact of malnutrition risk on primary poor outcomes at 3 months of follow-up, OR with 95 % CI were estimated by a univariate and multivariable-adjusted logistic regression model, respectively. The multivariable analyses were used to examine the association of CONUT or NRS-2002 scores with the primary outcomes (poor functional prognosis assessed by mRS). Age, gender, BMI, lifestyle factors, NIHSS scores and marginally unbalanced variables at baseline (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and Batherl Index) that may have potential impacts on the prognostic endpoints were taken as covariates adjusted in the multivariable model. All data were performed by the IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20.0). ROC with a calculation of the AUC was made by Medcalc (version 19.5.3), and the difference in the AUC was compared between the CONUT and NRS-2002 score groups by using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Results

Among 349 AHS patients, 328 patients were successfully followed for 3 months after discharge. Of these, the mean age was 60·38 years, and the proportions of men were 66·77 %. In total, 172 (52·44 %) patients were at malnutrition risk assessed by using the CONUT score, 104 (31·71 %) at malnutrition risk by the NRS-2002 and 16 (4·88 %) at malnutrition status with BMI < 18·5 kg/m2.

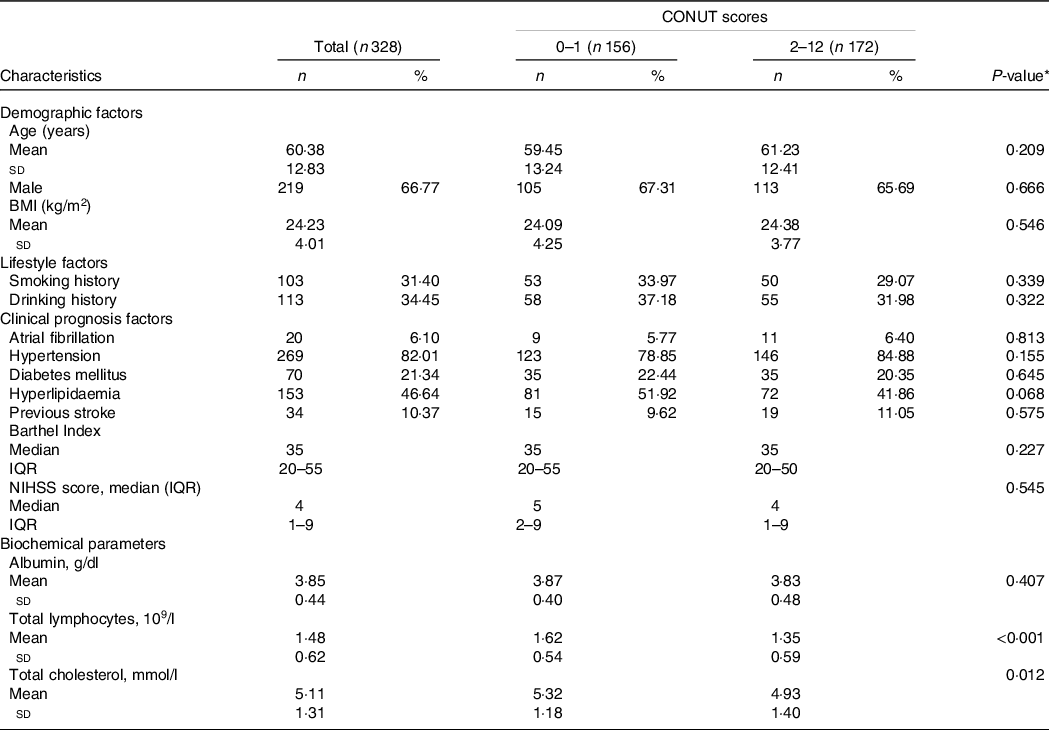

Baseline characteristics

The AHS participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. The levels of total lymphocytes and total cholesterol were lower in the low-CONUT compared with the high-CONUT groups (P < 0·001 and P = 0·012, respectively). The high-CONUT patients tend to have lower proportions of hyperlipaemia and higher hypertension than the low-CONUT patients, but the differences did not reach a statistical significance (P = 0·068 and P = 0·155, respectively). No statistical differences were found between the two groups in demographic (age, gender and BMI), lifestyle (smoking and drinking history) and other clinical characteristics (prevalent comorbidities and stroke-related scale assessments).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics by controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in the acute haemorrhagic stroke (AHS) patients

(Number and percentages; median and interquartile ranges; mean values and standard deviations)

NIHSS, National Institute of Health stroke scale; IQR, interquartile range.

* P values indicate a statistical significance between low-CONUT and high-CONUT score groups by using a t test.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The comparison of primary and secondary outcomes between the low-CONUT and high-CONUT groups is presented in Table 2. In total, 104 (31·71 %) patients had primary poor outcomes according to the mRS assessment, with a higher proportion of poor prognosis in the high-CONUT than that in the low-CONUT groups (38·37 vs. 24·36, P = 0·010). For individual secondary outcomes, patients at risk of malnutrition (high-CONUT scores) had more hospitalisation costs (P = 0·021), NIHSS scores (P = 0·012), nutritional support (P = 0·007) during hospitalisation and infectious complications (P = 0·002) as well as a lower Barthel Index (P = 0·001) post discharge than those at no or low risk.

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes grouped by controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in the acute haemorrhagic stroke (AHS) patients

(Number and percentages; median and interquartile ranges)

NIHSS, National Institute of Health stroke scale; IQR, interquartile range.

* P values indicate a statistical significance between low-CONUT and high-CONUT score groups by using a t test.

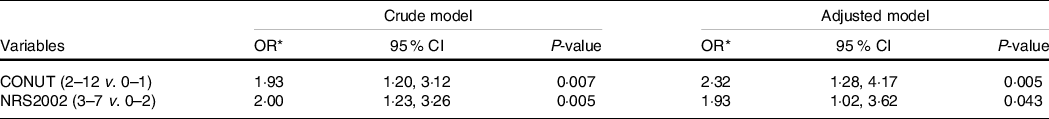

Poor outcome in relation to controlling nutritional status and Nutritional Risk Screening index-2002 scores

Association of the CONUT and NR-S2002 scores with a 3-month poor prognosis in the AHS patients is presented in Table 3. Patients with high-CONUT scores had a higher risk of the poor functional prognosis than those with low-CONUT scores (OR = 1·93; 95 % CI: 1·20, 3·12; P = 0·007), and this association remained to be statistically significant in the multivariate-adjusted model (adjusted OR = 2·32; 95 % CI: 1·28, 4·17; P = 0·005). Also, the high NRS-2002 scores of 3–7 were associated with the poor outcome compared with the low NRS-2002 scores of 1–2, with a crude OR of 2·00 (95 % CI: 1·23, 3·26; P = 0·005) and multivariable-adjusted OR of 1·93 (95 % CI: 1·02, 3·62; P = 0·043).

Table 3. Association of controlling nutritional status (CONUT) and Nutritional Risk Screening index (NRS200) with a 3-month poor prognosis in the acute haemorrhagic stroke patients

(Odd ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

* ORs with 95 % CIs for the incident 3-month poor functional outcome were estimated by using a crude or multivariate logistic model with adjustments for age, gender, BMI, lifestyle factors, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, NIHSS scores and Batherl Index, respectively.

Subgroup analyses

Pre-specified subgroup analyses on the CONUT score in predicting the 3-month poor AHS outcomes are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Compared with no malnutrition risk assessed by the low-CONUT score, malnutrition risk by high-CONUT score was associated with poor functional outcomes in the following strata of male (OR = 2·70; 95 % CI: 1·28, 5·68; P = 0·009), age ≤ 65 (OR = 2·71; 95 % CI: 1·28, 5·74; P = 0·009), hypertension (OR = 2·12; 95 % CI: 1·11, 4·04; P = 0·023), hyperlipidaemia (OR = 3·45; 95 % CI: 1·43–8·31; P = 0·006), Barthel Index ≤ 60 (OR = 2·14; 95 % CI: 1·10, 4·16; P = 0·024) and NIHSS < 8 (OR = 2·98; 95 % CI: 1·42, 6·23; P = 0·004), respectively.

Receiver operating characteristics curve

ROC with the estimated AUC comparisons between the CONUT and NRS-2002 scores in predicting the 3-month AHS prognosis is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S2. The estimated values of AUC were 0·58 (95 % CI: 0·52–0·64, P = 0·016; sensitivity: 63·46 %, specificity: 52·68 %) for the CONUT and 0·60 (95 % CI: 0·54–0·65, P < 0·001; sensitivity: 48·08 %, specificity: 73·21 %) for the NRS-2002, respectively (Table 4). No significant difference in the estimated AUC was found between the two scoring systems (P = 0·603).

Table 4. Receiver operator characteristic curve comparisons of the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) with Nutritional Risk Screening index (NRS)-2002 in predicting the 3-month acute haemorrhagic stroke prognosis

(Area under the curve and 95 % confidence intervals)

ROC, receiver operator characteristic curve; NSTs, Nutrition screening tools; mRS, the Modified Rankin Scale; NRS, Nutritional Risk Screening; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

* P value was calculated to indicate a statistical significance for the AUC with 95 % CI by using a Shapiro–Wilk test.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the patients with high-CONUT scores had a poor functional outcome evaluated by the MRS value of 3–6 compared with those with low-CONUT scores at 3 months of follow-up period. The CONUT, as a nutritional risk assessment tool easily calculated by biochemical parameters, seems to be comparable to that of the well-known NRS-2002 in predicting a functional prognosis in AHS. Such findings provide new evidence to support the prognostic value of CONUT in AHS patients and to further develop a novel notion that the CONUT helps to identify AHS patients who need additional nutritional managements, which may complement the gap in the AHS-related clinical practice. Furthermore, AHS survivors are vulnerable to malnutrition. Individualised nutritional treatment has been associated with improved outcomes in activities of daily living in stroke patients at risk of malnutrition(Reference Nishioka, Wakabayashi and Nishioka26,Reference Otsuki, Himuro and Tatsumi27) . Thus, early screening and identification of individuals who are at malnutrition risk are vital to ensure that the timeing nutritional managements may contribute to more benefits for the functional recovery in AHS clinical practice.

One major finding of our study is that the CONUT could be applied to assess the malnutrition risk in the AHS patients. Based on the accumulating evidence from extensive clinical studies, stroke patients may have a high risk of malnutrition, which, in turn, is clearly related to a poor clinical prognosis(Reference Nip, Perry and McLaren28,Reference Ojo and Brooke29) . To precisely predict the functional prognosis in clinical practice, there are currently many clinical guidelines that recommend the necessity for nutritional risk screening and nutritional management in stroke(Reference Serra30,Reference Hankey31) . NRS-2002 score has been widely used to screen the nutritional risk with a high sensitivity and accuracy(Reference Poulia, Klek and Doundoulakis32,Reference Sanson, Sadiraj and Barbin33) . It has good reliability and has been recommended as a screening tool for impaired nutritional status in populations in different settings, particularly in inpatients and elderly patients(Reference Kondrup, Allison and Elia34–Reference Mueller, Compher and Ellen36). Unfortunately, the NRS-2002, in which the items need to be obtained by face-to-face inquiry, is not well applied in one-third of stroke patients who have experienced aphasia. Alternatively, as an emerging screening tool, CONUT has been widely used for the nutritional risk assessment in many hospitalised patients, including the acute ischaemic stroke patients(Reference Naito, Hosomi and Nezu37,Reference Shiga, Nezu and Hosomi38) . In addition, the CONUT has multiple advantages. It could be calculated from three laboratory indicators including serum albumin, lymphocytes and total cholesterol during hospitalisation, which makes the screening procedure reliable and efficient. Also, this screening tool could be carried out without a substantial increase in the financial burden. Earlier findings have applied the CONUT to assess risk of malnutrition in patients with CVD(Reference Nakamura, Kamiya and Matsunaga39), traumatic brain injury(Reference Wang, He and Kang16) and those with Crohn’s disease(Reference Dong, Tang and Liu17).

Another major result from our study showed that patients with malnutrition risk determined using the CONUT score had higher rates of poor AHS outcomes than those without, and the malnutrition risk assessed by the CONUT was found to be positively associated with a poor prognosis. The CONUT has been widely used to predict prognosis in cancer and postoperative patients(Reference Kheirouri and Alizadeh13), and recent epidemiological studies have well documented the prognostic role of the CONUT score in acute ischaemic stroke(Reference Gon, Kabata and Kawano12,Reference Naito, Hosomi and Nezu37) . Compared with the previous studies, our current study found that the post-discharge patients with risk of malnutrition, according to CONUT score, were more likely to have higher NIHSS scores, rates of infectious complications, and hospitalisation costs as well as lower Barthel Index. The AHS patients with nutritional risk also showed higher adverse functional prognosis at 3 months follow-up, as illustrated by mRS ≥ 3, and the risk of malnutrition based on CONUT was associated with 3-month prognosis. In addition, ROC analyses found that the NRS-2002 was not superior to the CONUT as a comprehensive nutritional indicator, suggesting that both CONUT and NRS-2002 scores are likely to be equally effective in predicting the AHS prognosis. Give an operational merit with a simple application in clinical follow-up, the CONUT might be preferentially recommend for evaluating the malnutrition risk in AHS patients on admission.

In stratified analyses, the prognostic value of CONUT in AHS was more significant in male, patients with age at less than 65 years, prevalent hypertension, Barthel Index ≤ 60 and NIHSS scores < 8. There are several possible reasons for explaining the current subgroup findings. First, men lose more lean mass than women with the development of ageing, which perhaps resulted in a higher risk of poor prognosis in male than in female patients. For example, in an observational epidemiological study of 3286 elderly patients, the effects of malnutrition in men on health-related quality of life were stronger than in women(Reference Kvamme, Olsen and Florholmen40). Another possibility was that there appeared to be some additional impacts on the estimated prediction with the CONUT scores, such as the damage degree of stroke. As defined by Barthel Index ≤ 60, AHS patients experienced a moderate to severe decline in ADL on admission that is confirmed to be associated with a poor prognosis. In contrast, in patients with a mild decline in ADL, patients with nutritional risk had a 37 % higher risk of poor prognosis than those without, but this trend was not statistically significant. Similar predictive results were also more significant in the subgroup with the NIHSS scores < 8 and Barthel Index < 60, but the lack of statistical significance may be attributed to the small sample sizes of the two individual subgroups with NIHSS ≥ 8 or Barthel Index > 60. Thus, nutrition screening by CONUT should be carried out in AHS regardless of the influence to ADL or the severity of the disease. Third, patients with hypertension tended to have nutrition risk or prevalent malnutrition(Reference Hsieh, Hung and Chang2), and malnutrition survivors are likely to develop excess hypertension in later in life(Reference Tennant, Barnett and Thompson41). Our subgroup analysis showed the CONUT score in predicting AHS outcome was more significant in patients with BMI ≥ 18·5, hypertension or dyslipidaemia than in those without. The metabolic risk factors would contribute to the poor functional outcomes in AHS patients, thereby perhaps increasing the opportunity to observe the prognostic effects of the CONUT in AHS.

Our study has several strengths. First, this is the first clinical prospective study that aimed to investigate whether the malnutrition risk determined by CONUT would have a more prognostic value in AHS. Compared with the well-confirmed NRS-2002 score, the CONUT could be considered as a simpler nutritional indicator in predicting AHS prognosis. Second, selection bias is likely to be minimised because we did not exclude the patients who lack the ability to communicate with investigators. Third, our findings of the malnutrition risk assessed by the CONUT as a prognostic marker in AHS may contribute to an updated change in stroke-related clinical practice.

There are some weaknesses that merit further considerations. First, the number of sample patients is not large enough to reach a potent statistic power. Second, the 3-month duration of follow-up is relatively short, thus the current findings should be explained with caution and need to be verified in a further long-term prospective study. Third, since a standardised procedure in nutrition risk assessment is currently lacking, it is difficult to compare the sensitivity and specificity of CONUT with NRS-2002 in predicting outcomes. Forth, due to the lack of details in nutritional information with regard to dietary intake, the individual nutrition impacts upon the endpoints could not be eliminated. Further prospective clinical studies are needed to determine whether nutritional intervention or therapy would improve the prognostic outcome. Last, the laboratory measurement in the three components of the CONUT may have been affected by concurrent disorders such as inflammatory diseases at admission, and thus it is necessary to conduct the nutritional risk assessment determined by using the CONUT scores at regular intervals during the period of the follow-up.

In conclusion, AHS patients with malnutrition risk had a poorer prognosis than those without at 3 months of follow-up, and the malnutrition status assessed using the CONUT score was associated with a poor functional outcome in AHS. Given simplicity and convenience required in clinical practice, the CONUT scores could be advised to apply to identify the AHS patients who are at risk of malnutrition. Further effective nutritional support and special care should be administered to prevent poorer outcomes in post-stroke.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the patients with stroke who participated in the study and all of the medical staff who carefully finished the followed-up clinical measures to ensure that the study was conducted.

This research was funded by the 2017 Chinese Nutrition Society (CNS) Nutrition Research Foundation – DSM Research Fund (grant number: 2017-008) and the Wenzhou Science and Technology Bureau Fund (grant number: Y20190561 & Y20190556).

Conceptualisation, B. Y., B. L. Z. and M. M. Z.; methodology, M. M. Z. and B. L. Z.; validation, B. Y., B. L. Z. and M. M. Z.; formal analysis, Y. Z. W. and Z. M. C.; investigation, Y. Z. W., Z. M. C., C. W. L., Z. P. L., H. M. C.; resources, X. R. H., L. Q. S., Q. L. L. and X. D. Z.; data curation, Y. Z. W., R. Q. F. and S. L. Y.; writing and original draft preparation, B. L. Z., Y. Z. W., R. Q. F. and S. L. Y.; writing. review and editing, B. Y., L. W., B. L. Z., M. M. Z. and Z. M. C.; supervision, B. Y. and B. L. Z.; project administration, Y. Z. W., X. R. H., L. Q. S., Q. L. L. and X. D. Z.; funding acquisition, B. Y., B. L. Z. and M. M. Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521003184