1. Introduction

We are interested in the following problem.

Problem 1.

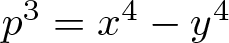

Let k be a perfect field of characteristic not equal to 2. Let K be a finite extension of k. Let ![]() $D\in k^*$. Find all solutions to the equation

$D\in k^*$. Find all solutions to the equation

By a solution (x, y) to Equation (1), we always mean ![]() $(x,y)\in \mathbb{A}^2(K)$ satisfying Equation (1) and xy ≠ 0.

$(x,y)\in \mathbb{A}^2(K)$ satisfying Equation (1) and xy ≠ 0.

When ![]() $k=K=\mathbb{Q}$, using a variety of methods, many authors have shown that Equation (1) has no solutions if

$k=K=\mathbb{Q}$, using a variety of methods, many authors have shown that Equation (1) has no solutions if ![]() $D=nz^p$ for integers n and prime numbers p; see [Reference Bajolet, Dupuy, Luca and Togbe1, Reference Bennett2, Reference Cao4, Reference Dabrowski6, Reference Darmon7, Reference Savin11].

$D=nz^p$ for integers n and prime numbers p; see [Reference Bajolet, Dupuy, Luca and Togbe1, Reference Bennett2, Reference Cao4, Reference Dabrowski6, Reference Darmon7, Reference Savin11].

It is natural to ask for solutions of Equation (1) when k and K are not the rational field. When k and K are number fields, since Equation (1) defines a curve of genus 3, by Faltings’ theorem [Reference Faltings8], Equation (1) only has a finite number of solutions, but to find all solutions to Equation (1) is in general a difficult task. We adopt here the method of Cassels’ [Reference Cassels5] and Bremner’s [Reference Bremner3], which is effective in finding solutions to Equation (1) in all cubic extensions of the base field in many situations. It is also worth mentioning that the work of Silverman [Reference Silverman13] on the equation ![]() $x^4+y^4=D$ (and

$x^4+y^4=D$ (and ![]() $x^6+y^6=D$) over number fields. But Silverman’s method does not apply when finding solutions in cubic extensions of the base field. The main result of this paper is as follows:

$x^6+y^6=D$) over number fields. But Silverman’s method does not apply when finding solutions in cubic extensions of the base field. The main result of this paper is as follows:

Theorem 1. Let k be a perfect field of characteristic not equal to 2. Let ![]() $D\in k$ such that

$D\in k$ such that ![]() $D\not\in \pm k^2$. Assume that

$D\not\in \pm k^2$. Assume that

(i) every solution

$(X,y,z)\in \mathbb{A}^3(k)$ to

$(X,y,z)\in \mathbb{A}^3(k)$ to  $X^2-y^4=Dz^4$ satisfies z = 0,

$X^2-y^4=Dz^4$ satisfies z = 0,(ii) every solution

$(x,Y,z)\in \mathbb{A}^3(k)$ to

$(x,Y,z)\in \mathbb{A}^3(k)$ to  $x^4-Y^2=Dz^4$ satisfies z = 0.

$x^4-Y^2=Dz^4$ satisfies z = 0.

If (x, y) is a solution to ![]() $D=x^4-y^4$ in a cubic extension K of k, then

$D=x^4-y^4$ in a cubic extension K of k, then

(1) (if

$-1\not \in k^2$)

where

$-1\not \in k^2$)

where \begin{equation*}K=k(\theta),\quad

x=\pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\quad y= \pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}K=k(\theta),\quad

x=\pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\quad y= \pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),

\end{equation*} $\theta^3-s^2\theta^2/8-2D^2/s^2=0$ and

$\theta^3-s^2\theta^2/8-2D^2/s^2=0$ and  $s\in k^{*}$, and

$s\in k^{*}$, and(2) (if

$-1\in k^2$)

where

$-1\in k^2$)

where \begin{equation*}K=k(\theta),\quad

x=\pm \left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\quad y=\pm i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}K=k(\theta),\quad

x=\pm \left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\quad y=\pm i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),

\end{equation*} $i=\sqrt{-1}$,

$i=\sqrt{-1}$,  $\theta^3+s^4\theta/16+Ds^2/2=0$, and

$\theta^3+s^4\theta/16+Ds^2/2=0$, and  $s\in k^{*}$.

$s\in k^{*}$.

A nice corollary of Theorem 1 is

Corollary 1. Let p be a prime number. Let D = p if ![]() $p\equiv 11$ (mod 16), and let

$p\equiv 11$ (mod 16), and let ![]() $D=p^3$ if

$D=p^3$ if ![]() $p\equiv 3$ (mod 16). Then solutions to

$p\equiv 3$ (mod 16). Then solutions to ![]() $D=x^4-y^4$ in all cubic extensions of

$D=x^4-y^4$ in all cubic extensions of ![]() $\mathbb{Q}(i)$ are

$\mathbb{Q}(i)$ are

(1)

\begin{equation*}x=\pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad y= \pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}x=\pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad y= \pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\end{equation*}where

$\theta^3-s^2\theta^2/8-2D^2/s^2=0$ for some

$\theta^3-s^2\theta^2/8-2D^2/s^2=0$ for some  $s\in \mathbb{Q}(i)^{*}$; and

$s\in \mathbb{Q}(i)^{*}$; and(2)

\begin{equation*}

x=\pm \left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad y=\pm i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

x=\pm \left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad y=\pm i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right),

\end{equation*}where

$\theta^3+s^4\theta/16+Ds^2/2=0$ for some

$\theta^3+s^4\theta/16+Ds^2/2=0$ for some  $s\in \mathbb{Q}(i)^{*}$.

$s\in \mathbb{Q}(i)^{*}$.

Remark 1. Theorem 1 finds all possible cubic extensions K of k and solutions to ![]() $D=x^4-y^4$ in K. The defining polynomial of K,

$D=x^4-y^4$ in K. The defining polynomial of K, ![]() $F_s(x)=x^3-s^2x^2/8-2D^2/s^2$ or

$F_s(x)=x^3-s^2x^2/8-2D^2/s^2$ or ![]() $F_s(x)=x^3+s^4x/16+Ds^2/2$, must be irreducible in

$F_s(x)=x^3+s^4x/16+Ds^2/2$, must be irreducible in ![]() $k[x]$, which in general is difficult to check since the irreducibility of

$k[x]$, which in general is difficult to check since the irreducibility of ![]() $F_s(x)$ depends on s. However, if k is a number field, by Hilbert’s irreducibility theorem [Reference Serre12, Theorem 3.4.1], there exist infinitely many

$F_s(x)$ depends on s. However, if k is a number field, by Hilbert’s irreducibility theorem [Reference Serre12, Theorem 3.4.1], there exist infinitely many ![]() $s\in k$ such that

$s\in k$ such that ![]() $F_s(x)$ is irreducible in

$F_s(x)$ is irreducible in ![]() $k[x]$ and Theorem 1 finds all solutions to

$k[x]$ and Theorem 1 finds all solutions to ![]() $D=x^4-y^4$ in these cases.

$D=x^4-y^4$ in these cases.

2. Proof of Theorem 1

We follow Cassels [Reference Cassels5]. Equation (1) can be written in the homogeneous form

Let ![]() $\mathcal{C}$ be the projective curve over k defined by Equation (2). Suppose that

$\mathcal{C}$ be the projective curve over k defined by Equation (2). Suppose that ![]() $P=[x_1:y_1:z_1]$is a point on (2) whose coordinates generate a cubic extension K of k. If

$P=[x_1:y_1:z_1]$is a point on (2) whose coordinates generate a cubic extension K of k. If ![]() $z_1=0$, then

$z_1=0$, then ![]() $[x_1:y_1:z_1]=[\pm 1:1:0]$; therefore K = k, which is impossible. Therefore,

$[x_1:y_1:z_1]=[\pm 1:1:0]$; therefore K = k, which is impossible. Therefore, ![]() $z_1\neq 0$. Since

$z_1\neq 0$. Since ![]() $(x_1/z_1)^4-(y_1/z_1)^4=D$ and

$(x_1/z_1)^4-(y_1/z_1)^4=D$ and ![]() $|K:k|=3$, we have

$|K:k|=3$, we have ![]() $x_1/z_1,y_1/z_1\not\in k$. Thus,

$x_1/z_1,y_1/z_1\not\in k$. Thus,

\begin{equation}

k\left(\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}\right)=k\left(\dfrac{y_1}{z_1}\right)= k\left(\dfrac{x_1^2}{z_1^2}\right)=k\left(\dfrac{y_1^2}{z_1^2}\right)=K.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

k\left(\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}\right)=k\left(\dfrac{y_1}{z_1}\right)= k\left(\dfrac{x_1^2}{z_1^2}\right)=k\left(\dfrac{y_1^2}{z_1^2}\right)=K.

\end{equation} Fix an algebraic closure ![]() $\overline{k}$ of k. Let

$\overline{k}$ of k. Let ![]() $P_i=[x_i:y_i:z_i] \in \mathbb{P}^{2}(\overline{k})$,

$P_i=[x_i:y_i:z_i] \in \mathbb{P}^{2}(\overline{k})$, ![]() $i=1,2,3$, be the Galois conjugates of P. The equation

$i=1,2,3$, be the Galois conjugates of P. The equation

has a parametrization

Since ![]() $[x_1^2:y_1^2:z_1^2]$ satisfies Equation (4), there exist

$[x_1^2:y_1^2:z_1^2]$ satisfies Equation (4), there exist ![]() $\lambda,\mu\in k$ such that

$\lambda,\mu\in k$ such that

Since ![]() $z_1\neq 0$, it follows from Equation (5) that µ ≠ 0, λ ≠ 0, and

$z_1\neq 0$, it follows from Equation (5) that µ ≠ 0, λ ≠ 0, and

Let ![]() $\theta=\lambda/\mu$. Then Equations (3) and (6) show that

$\theta=\lambda/\mu$. Then Equations (3) and (6) show that ![]() $\theta \not \in k$. Hence,

$\theta \not \in k$. Hence, ![]() $k(\theta)=K$. Therefore, there exists an irreducible cubic polynomial

$k(\theta)=K$. Therefore, there exists an irreducible cubic polynomial ![]() $P(x)=ax^3+bx^2+cx+d \in k[x]$ such that

$P(x)=ax^3+bx^2+cx+d \in k[x]$ such that ![]() $P(\theta)=0$. In particular, ad ≠ 0. From Equation (5), we have

$P(\theta)=0$. In particular, ad ≠ 0. From Equation (5), we have

\begin{equation}

\left(\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}\right)^2:\left(\dfrac{y_1}{z_1}\right)^2=\dfrac{\theta^2+D}{2\theta}:\dfrac{\theta^2-D}{2D}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left(\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}\right)^2:\left(\dfrac{y_1}{z_1}\right)^2=\dfrac{\theta^2+D}{2\theta}:\dfrac{\theta^2-D}{2D}.

\end{equation}Step 1: Consider the weighted projective curve

By points on ![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$, we mean the equivalence classes of points

$\mathcal{C}_1$, we mean the equivalence classes of points ![]() $[X:y:z]$ in

$[X:y:z]$ in  $\mathbb{P}^2_{2,1,1}(\overline{k})$ satisfying Equation (8). Since

$\mathbb{P}^2_{2,1,1}(\overline{k})$ satisfying Equation (8). Since ![]() $x_i^2,y_i^2,y_iz_i,z_i^2$ are linearly dependent over k and

$x_i^2,y_i^2,y_iz_i,z_i^2$ are linearly dependent over k and ![]() $x_i\neq 0$, there exist

$x_i\neq 0$, there exist ![]() $r,s,t\in \mathbb{Q}$ such that

$r,s,t\in \mathbb{Q}$ such that

for ![]() $i=1,2,3$. Consider the weighted projective curve

$i=1,2,3$. Consider the weighted projective curve

By the weighted Bézout theorem [Theorem VIII.2][Reference Mondal10], the two curves ![]() $\mathcal{C}_1$ and

$\mathcal{C}_1$ and ![]() $\mathcal{D}_1$ intersect at 4 points in

$\mathcal{D}_1$ intersect at 4 points in  $\mathbb{P}_{2,1,1}^2(\overline{k})$. We know that three of these four points are

$\mathbb{P}_{2,1,1}^2(\overline{k})$. We know that three of these four points are ![]() $[x_i^2:y_i:z_i]$ for

$[x_i^2:y_i:z_i]$ for ![]() $i=1,2,3$. Let

$i=1,2,3$. Let ![]() $v_1(T)$ be the fourth point of intersection. Since the set

$v_1(T)$ be the fourth point of intersection. Since the set ![]() $\{[x_i^2:y_i:z_i]:i=1,2,3\}$ is stable under the action of

$\{[x_i^2:y_i:z_i]:i=1,2,3\}$ is stable under the action of ![]() $\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$,

$\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$, ![]() $v_1(T)$ is fixed by

$v_1(T)$ is fixed by ![]() $\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$. Therefore,

$\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$. Therefore, ![]() $v_1(T)$ is a k-rational point. By the assumption in Theorem 1, we have

$v_1(T)$ is a k-rational point. By the assumption in Theorem 1, we have ![]() $v_1(T)=[\pm 1:1:0]$.

$v_1(T)=[\pm 1:1:0]$.

![]() $\bullet$

$\bullet$ ![]() $v_1(T)=[1:1:0]$. Then Equation (9) gives r = 1. Since

$v_1(T)=[1:1:0]$. Then Equation (9) gives r = 1. Since

the homogeneous quartic in ![]() $l,m$,

$l,m$,

has factors m and ![]() $P(l,m)$. Therefore, there exists

$P(l,m)$. Therefore, there exists ![]() $q\in k$ such that

$q\in k$ such that

\begin{align}

(l^2+Dm^2-(l^2-Dm^2)-2tlm)^2-2lms^2(l^2-Dm^2)=& 2qm(al^3+bl^2m\\& +clm^2+dm^3).

\end{align}

\begin{align}

(l^2+Dm^2-(l^2-Dm^2)-2tlm)^2-2lms^2(l^2-Dm^2)=& 2qm(al^3+bl^2m\\& +clm^2+dm^3).

\end{align}Thus,

Therefore,

\begin{equation}\begin{cases}qa&=-s^2,\\

qb&=2t^2,\\

qc&=Ds^2-4Dt,\\

qd&=2D^2.

\end{cases}\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\begin{cases}qa&=-s^2,\\

qb&=2t^2,\\

qc&=Ds^2-4Dt,\\

qd&=2D^2.

\end{cases}\end{equation}Hence,

Therefore,

Since ![]() $a,d\neq 0$, system (11) gives

$a,d\neq 0$, system (11) gives

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv -2\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv -2\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation} ![]() $\bullet$

$\bullet$ ![]() $v_1(T)=[-1:1:0]$. Then Equation (9) gives

$v_1(T)=[-1:1:0]$. Then Equation (9) gives ![]() $r=-1$. Since

$r=-1$. Since

the homogeneous quartic in ![]() $l,m,$

$l,m,$

has factors l and ![]() $P(l,m)$. Therefore, there exists

$P(l,m)$. Therefore, there exists ![]() $q\in k$ such that

$q\in k$ such that

Hence,

Therefore,

\begin{equation}

\begin{cases}

qa&=2,\\

qb&=-4t-s^2,\\

qc&=2t^2,\\

qd&=Ds^2.

\end{cases}\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{cases}

qa&=2,\\

qb&=-4t-s^2,\\

qc&=2t^2,\\

qd&=Ds^2.

\end{cases}\end{equation}Hence,

\begin{equation*}

q^2ac=4t^2,\quad

q\left(b+\dfrac{d}{D}\right)=-4t,\ q\neq 0.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

q^2ac=4t^2,\quad

q\left(b+\dfrac{d}{D}\right)=-4t,\ q\neq 0.\end{equation*}Therefore,

\begin{equation}

\left(b+\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2=4ac.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left(b+\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2=4ac.\end{equation} Since ![]() $a,d\neq 0$, system (15) also gives

$a,d\neq 0$, system (15) also gives

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv 2D\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv 2D\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation}Step 2: Consider the weighted projective curve

By points on ![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$, we mean the equivalence classes of points

$\mathcal{C}_2$, we mean the equivalence classes of points ![]() $[x:Y:z]$ in

$[x:Y:z]$ in  $\mathbb{P}^2_{1,2,1}(\overline{k})$ satisfying Equation (18). Since

$\mathbb{P}^2_{1,2,1}(\overline{k})$ satisfying Equation (18). Since ![]() $y_i^2,x_i^2,x_iz_i,z_i^2$ are linearly dependent over k and

$y_i^2,x_i^2,x_iz_i,z_i^2$ are linearly dependent over k and ![]() $y_i\neq 0$, there exist

$y_i\neq 0$, there exist ![]() $r,s,t\in \mathbb{Q}$ such that

$r,s,t\in \mathbb{Q}$ such that

for ![]() $i=1,2,3$. Consider the weighted projective curve

$i=1,2,3$. Consider the weighted projective curve

By the weighted Bézout theorem [Theorem VIII.2][Reference Mondal10], the two curves ![]() $\mathcal{C}_2$ and

$\mathcal{C}_2$ and ![]() $\mathcal{D}_2$ intersect at 4 points in

$\mathcal{D}_2$ intersect at 4 points in  $\mathbb{P}_{1,2,1}^2(\overline{k})$. We know that three of these four points are

$\mathbb{P}_{1,2,1}^2(\overline{k})$. We know that three of these four points are ![]() $[x_i:y_i^2:z_i]$ for

$[x_i:y_i^2:z_i]$ for ![]() $i=1,2,3$. Let

$i=1,2,3$. Let ![]() $v_2(T)$ be the fourth point of intersection. Since the set

$v_2(T)$ be the fourth point of intersection. Since the set ![]() $\{[x_i:y_i^2:z_i]:i=1,2,3\}$ is stable under the action of

$\{[x_i:y_i^2:z_i]:i=1,2,3\}$ is stable under the action of ![]() $\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$,

$\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$, ![]() $v_2(T)$ is fixed by

$v_2(T)$ is fixed by ![]() $\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$. Therefore,

$\operatorname{Gal}(\overline{k}/k)$. Therefore, ![]() $v_2(T)$ is a k-rational point. By the assumption in Theorem 1, we have

$v_2(T)$ is a k-rational point. By the assumption in Theorem 1, we have ![]() $v_2(T)=[1:\pm 1:0]$.

$v_2(T)=[1:\pm 1:0]$.

![]() $\bullet$

$\bullet$ ![]() $v_2(T)=[1:1:0]$. Then Equation (19) gives r = 1. We have

$v_2(T)=[1:1:0]$. Then Equation (19) gives r = 1. We have

so that the homogeneous quartic in ![]() $l,m,$

$l,m,$

has factors m and ![]() $P(l,m)$. Therefore, there exists

$P(l,m)$. Therefore, there exists ![]() $q\in k$ such that

$q\in k$ such that

Thus,

Hence,

\begin{equation}\begin{cases}

qa&=-s^2,\\

qb&=2r^2,\\

qc&=4Dr-Ds^2,\\

qd&=2D^2.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\begin{cases}

qa&=-s^2,\\

qb&=2r^2,\\

qc&=4Dr-Ds^2,\\

qd&=2D^2.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}Therefore,

Hence,

Since ![]() $a,d\neq 0$, system (21) gives

$a,d\neq 0$, system (21) gives

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv -2\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv -2\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation} ![]() $\bullet$

$\bullet$ ![]() $v_2(T)=[1:-1:0]$. Then Equation (19) gives

$v_2(T)=[1:-1:0]$. Then Equation (19) gives ![]() $r=-1.$ We have

$r=-1.$ We have

so that the homogeneous quartic in ![]() $l,m,$

$l,m,$

has factors l and ![]() $P(l,m)$. Thus, there exists

$P(l,m)$. Thus, there exists ![]() $q\in k$ such that

$q\in k$ such that

\begin{align}

(l^2-Dm^2+(l^2+Dm^2)-2tlm)^2-s^2(l^2+Dm^2)(2lm)=&2lq(al^3+bl^2m\\&+clm^2+dm^3).

\end{align}

\begin{align}

(l^2-Dm^2+(l^2+Dm^2)-2tlm)^2-s^2(l^2+Dm^2)(2lm)=&2lq(al^3+bl^2m\\&+clm^2+dm^3).

\end{align}Hence,

Therefore,

\begin{equation}\begin{cases}

qa&=2,\\

qb&=-4t-s^2,\\

qc&=2t^2,\\

qd&=-Ds^2.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\begin{cases}

qa&=2,\\

qb&=-4t-s^2,\\

qc&=2t^2,\\

qd&=-Ds^2.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}Hence,

\begin{equation*}

q^2ac=4t^2,\quad

q\left(b-\dfrac{d}{D}\right)=-4r,\ q\neq 0.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

q^2ac=4t^2,\quad

q\left(b-\dfrac{d}{D}\right)=-4r,\ q\neq 0.\end{equation*}Thus,

\begin{equation}

\left(b-\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2=4ac.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left(b-\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2=4ac.

\end{equation}System (25) also gives

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv -2D\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a}{d}\equiv -2D\pmod{k^2}.

\end{equation} It follows from (23), (27), (13) and (17) and the assumption that ![]() $D\not\in \pm k^2$ that there are only two compatible cases for

$D\not\in \pm k^2$ that there are only two compatible cases for ![]() $v_1(T)$ and

$v_1(T)$ and ![]() $v_2(T)$.

$v_2(T)$.

Case 1: ![]() $v_1(T)=[1:1:0]$ and

$v_1(T)=[1:1:0]$ and ![]() $v_2(T)=[1:1:0]$. From (12) and (22), we have

$v_2(T)=[1:1:0]$. From (12) and (22), we have

Since aD ≠ 0, we have c = 0. From (21), we have ![]() $r=s^2/4$. Thus,

$r=s^2/4$. Thus,

\begin{equation*}{qP(x)=-s^2x^3+\dfrac{s^4}{8}x^2+2D^2.}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{qP(x)=-s^2x^3+\dfrac{s^4}{8}x^2+2D^2.}\end{equation*}Therefore θ satisfies

\begin{equation}

\theta^3-\dfrac{s^2}{8}\theta^2-2\dfrac{D^2}{s^2}=0.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\theta^3-\dfrac{s^2}{8}\theta^2-2\dfrac{D^2}{s^2}=0.

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\dfrac{\theta^2+D}{2\theta}=\left(\dfrac{s}{4}+\dfrac{D}{2\theta}\right)^2,\qquad \dfrac{\theta^2-D}{2\theta}=\left(\dfrac{s}{4}-\dfrac{D}{2\theta}\right)^2.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{\theta^2+D}{2\theta}=\left(\dfrac{s}{4}+\dfrac{D}{2\theta}\right)^2,\qquad \dfrac{\theta^2-D}{2\theta}=\left(\dfrac{s}{4}-\dfrac{D}{2\theta}\right)^2.

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}=\pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad\dfrac{y_1}{z_1}= \pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}=\pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad\dfrac{y_1}{z_1}= \pm \left(\dfrac{D}{s\theta}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right).

\end{equation} Case 2: ![]() $v_1(T)=[-1:1:0]$ and

$v_1(T)=[-1:1:0]$ and ![]() $v_2(T)=[1:-1:0]$. This case also implies that

$v_2(T)=[1:-1:0]$. This case also implies that ![]() $-1\in k^2$. From (17) and (25), we have

$-1\in k^2$. From (17) and (25), we have

\begin{equation*}\left(b+\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2=\left(b-\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\left(b+\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2=\left(b-\dfrac{d}{D}\right)^2.\end{equation*} Since d ≠ 0, we have b = 0. Hence, from (15), we have ![]() $t=-s/4$. Therefore,

$t=-s/4$. Therefore,

\begin{equation*}qP(x)=2x^3+\dfrac{s^4}{8}x+Ds^2.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}qP(x)=2x^3+\dfrac{s^4}{8}x+Ds^2.\end{equation*}Therefore, θ satisfies

\begin{equation}

\theta^3+\dfrac{s^4}{16}\theta+\dfrac{Ds^2}{2}=0.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\theta^3+\dfrac{s^4}{16}\theta+\dfrac{Ds^2}{2}=0.

\end{equation}It follows from (14) and (24) that

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{\theta^2+D}{2\theta}=\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right)^2,\qquad \dfrac{\theta^2-D}{2\theta }=\left(i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right)\right)^2,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{\theta^2+D}{2\theta}=\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right)^2,\qquad \dfrac{\theta^2-D}{2\theta }=\left(i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right)\right)^2,\end{equation} where ![]() $i\in k$ such that

$i\in k$ such that ![]() $i^2=-1\in k$. From (7) and (32), we have

$i^2=-1\in k$. From (7) and (32), we have

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}=\pm \left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad \dfrac{y_1}{z_1}=\pm i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{x_1}{z_1}=\pm \left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}-\dfrac{s}{4}\right),\qquad \dfrac{y_1}{z_1}=\pm i\left(\dfrac{\theta}{s}+\dfrac{s}{4}\right).

\end{equation}3. Proof of Corollary 1

Corollary 1 is a consequence of Theorem 1 and the following lemma due to Izadi et al. [Reference Izadi, Naghdali and Brown9].

(1) For prime numbers,

$p\equiv 3$ (mod 16), then the equations

$p\equiv 3$ (mod 16), then the equations  $x^2{-}y^4={\pm} p^3z^4$ only have solutions

$x^2{-}y^4={\pm} p^3z^4$ only have solutions  $X=\pm y^2$ and z = 0 in

$X=\pm y^2$ and z = 0 in  $\mathbb{Q}(i)$.

$\mathbb{Q}(i)$.(2) For prime numbers,

$p\equiv 11$ (mod 16), then the equations

$p\equiv 11$ (mod 16), then the equations  $X^2{-}y^4={\pm} pz^4$ only have solutions

$X^2{-}y^4={\pm} pz^4$ only have solutions  $X=\pm y^2$ and z = 0 in

$X=\pm y^2$ and z = 0 in  $\mathbb{Q}(i)$.

$\mathbb{Q}(i)$.

Proof. See Izadi [Reference Izadi, Naghdali and Brown9, Theorems 3.2 and 3.4].

Acknowledgements

The author is supported by the Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) (grant number 101.04-2023.21).

Competing Interest

The author declares none.