Fish and seafood are widely consumed throughout the world(Reference Nesheim, Oria and Yih1) and are an important source of vitamins A, D and E, as well as essential n-3 fatty acids which contribute to healthy eye, brain and neurological development in babies and children(2). Seafood is also a major source of lean protein worldwide, and according to a report conducted by the FAO of the United Nations, approximately 6 % of dietary protein comes from seafood globally(Reference Nesheim, Oria and Yih1). Seafood is also generally rich in iodine, important in proper thyroid function, and its consumption can contribute towards meeting the daily requirement of 150 μg/d for adults(3). Whilst there are a number of positive reasons to consume seafood from a nutritional point of view, it is important to consider both sustainability of the type of seafood that is consumed(Reference Troell, Jonell and Crona4,Reference Willett, Rockstrom and Loken5) , as well as biotoxicity risk(Reference Sirot, Leblanc and Margaritis6,Reference Hellberg, DeWitt and Morrissey7) . The European Commission(8) recommends 1–4 servings of fish a week to maximise the health benefits as well as minimise biotoxicity risks associated with seafood consumption. From a sustainability aspect, the 2019 EAT-Lancet report recommends consumption of 28 g/d (up to 100 g) of fish to keep within planetary bounds and prevent depletion of fish stocks(Reference Troell, Jonell and Crona4). In Ireland and the UK, healthy eating guidelines currently recommend the consumption of two servings of about 140 g of fish/week, one to be oily fish. According to the Irish National Adult Nutrition Survey (2010) data, fish was consumed by half of 18–64-year-olds and two-thirds of those aged 65 years and over in the Republic of Ireland. However, the average daily intake of fish in National Adult Nutrition Survey consumers was approximately 50 g, which is below the recommended amounts(9).

Furthermore, intakes across European countries vary greatly(10) and national consumption surveys often lack information about less commonly consumed foods as data collection focuses on a snapshot of habitual diet(9). For example, in the last Irish national food consumption survey, from 133 050 rows of data generated, only twelve of these related to shellfish which is not sufficient data to assess contribution to nutrient intake or undertake risk exposure assessment in this food group.

This review aims to examine published literature from Western countries (Europe, Australia, New Zealand, USA and Canada) and investigate, at a time when consumers are moving to diversify their diet from animal-based protein(11), the characteristics of seafood consumers, as well as the barriers and influences on seafood consumption. Seafood is defined as ‘animals from the sea that can be eaten, especially fish or sea creatures with shells’; thus, this paper will focus on the consumption of both fish and shellfish.

Materials and methods

To our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the determinants of seafood consumption across multiple countries. Our primary objective was to characterise seafood consumers residing in Western countries (Europe, Australia, New Zealand, USA and Canada). The primary review question was ‘What are the characteristics of seafood consumers in developed countries?’. Secondary considerations included ‘What are the associations (positive and negative) on seafood consumption in these countries?’. A comprehensive search following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was conducted in Embase, MEDLINE and Web of Science of papers published between 1 October 2008 and 31 December 2018. Two additional searches for papers published between 1 January 2019 and 27 August 2019 were performed on 27 August 2019 and 29 August 2020, in order to identify any papers that were missed in the original search, using identical terms and databases as the initial search. The search strategy included a combination of the following search terms: ((factors OR influences OR determinants OR indicators) AND (fish OR seafood OR shellfish OR marine products) AND (diet OR dietary intake OR intake OR consumption)). When performing the search on the Web of Science database, categories were refined to ‘Nutrition and Dietetics’, ‘Behavioural Sciences’, ‘Public Environmental Occupational Health’ and ‘Environment Sciences’. For each concept, the database-specific indexing terms (MeSH or Web of Science terms) were searched in addition to terms in the title or abstract. Studies were only considered if meeting the following criteria – full-text articles on human studies conducted between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2018 among adults (18+ years) in Europe, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, published in English. The search was limited to adults (>18 years); studies involving children were excluded. Studies which did not statistically analyse associations between seafood consumption and the following factors were excluded: age, sex, education, affluence, BMI, physical activity and smoking. Included studies explored participants’ intakes of fish, seafood and/or proxy measures of same, such as marine PUFA or perceived barriers to or drivers of seafood/fish consumption.

In the final selected papers, the following key characteristics were captured: (a) study methodologies: the country and year of the study, the number of subjects and their sex, age (age range), intake of specific foods, food groups and/or nutrients being investigated, dietary assessment method and dietary analysis; (b) the characteristics of seafood consumers described in the study, findings of stratified analysis by sex, age, education, income, smoking, BMI or physical activity and (c) barriers to and drivers of seafood consumption that exist in these populations, which were consequently categorised under the following broader terms: personal preference, availability/convenience, cost, cooking skills, environment, health and nutritional beliefs and psychological traits.

Results

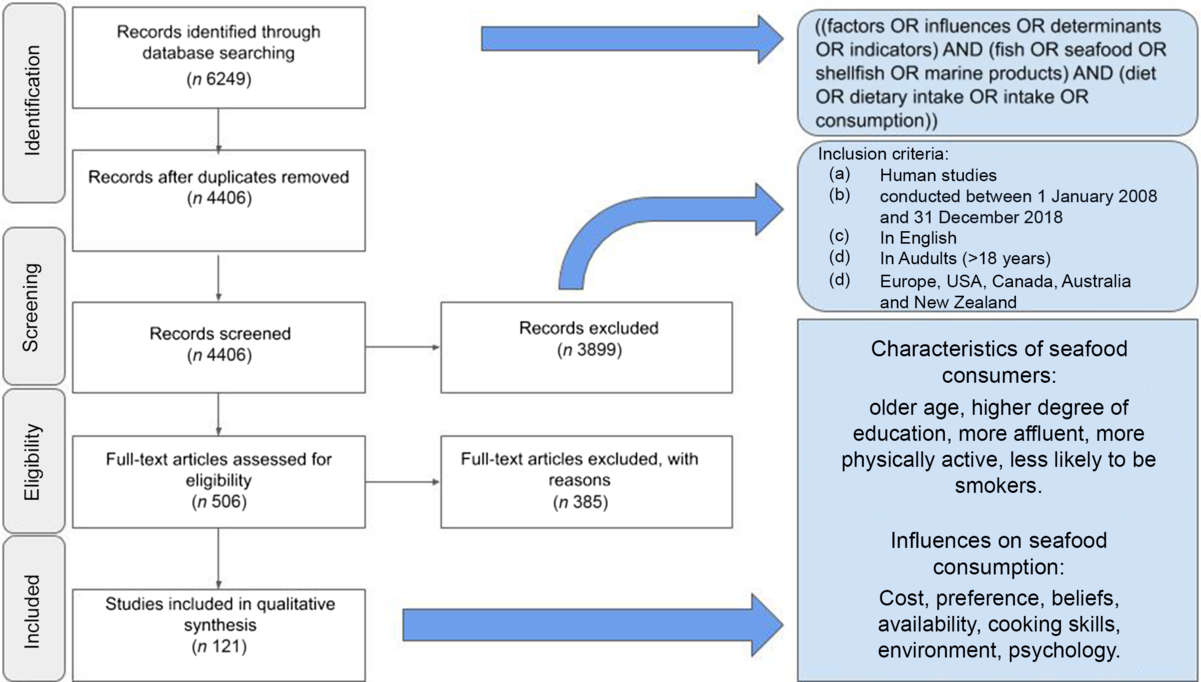

Combined, the three literature searches yielded 1961 titles of potentially relevant articles in PubMed, 1828 titles in Embase and 2460 titles in Web of Science. A total of 4406 unique articles were found, after duplicates were removed. Following this, a further 3899 articles were excluded following consideration of title and abstract. The remaining articles (n 506) were screened based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Two authors independently assessed abstracts of potentially eligible papers that examined fish and seafood intake and decided on inclusion of full-text articles, resolving any differences by discussion and, when necessary, in consultation with the review team. Of the remaining 121 articles, eighty-two articles explored the characteristics of seafood consumers and thirty-seven articles explored the barriers and/or influences on seafood consumption (Fig. 1). These papers and their findings are described below.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart of the searching and selection process.

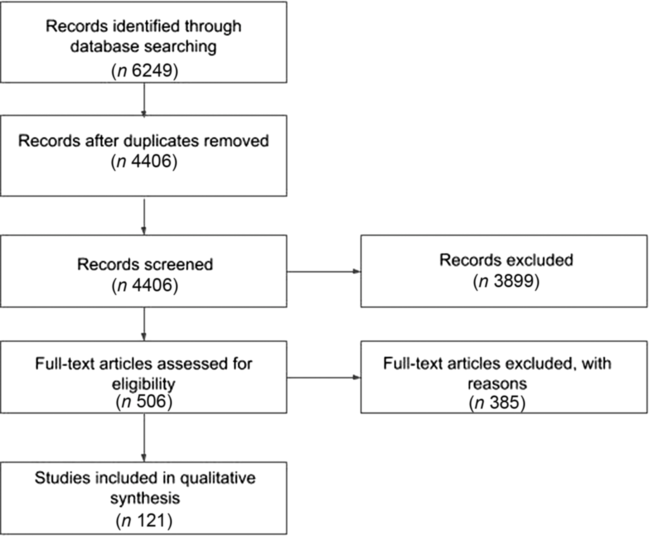

Details of each study included in this review are summarised in Table 1 and online Supplementary Table S1. Online Supplementary Table S1 lists the papers that analysed the characteristics of seafood consumers. Studies were conducted in the USA (n 27), Europe (n 49), Australia (n 2), New Zealand (n 1) and Canada (n 3). Sixty-seven percentage of all papers exploring the characteristics of seafood consumers collected dietary intake data using only a FFQ, 7 % used 24-h recalls, 5 % used a food record, 10 % used interviews and 9 % used a combination of these methods. Fifty-two studies had a cross-sectional design, and thirty were prospective observational studies. This review focuses on the following characteristics: age, sex, affluence, education, BMI, physical activity and smoking.

Table 1. Descriptions of studies that explored the barriers and drivers to seafood consumption

SES, socio-economic status; LCPUFA, long-chain PUFA.

Characteristics of seafood consumers

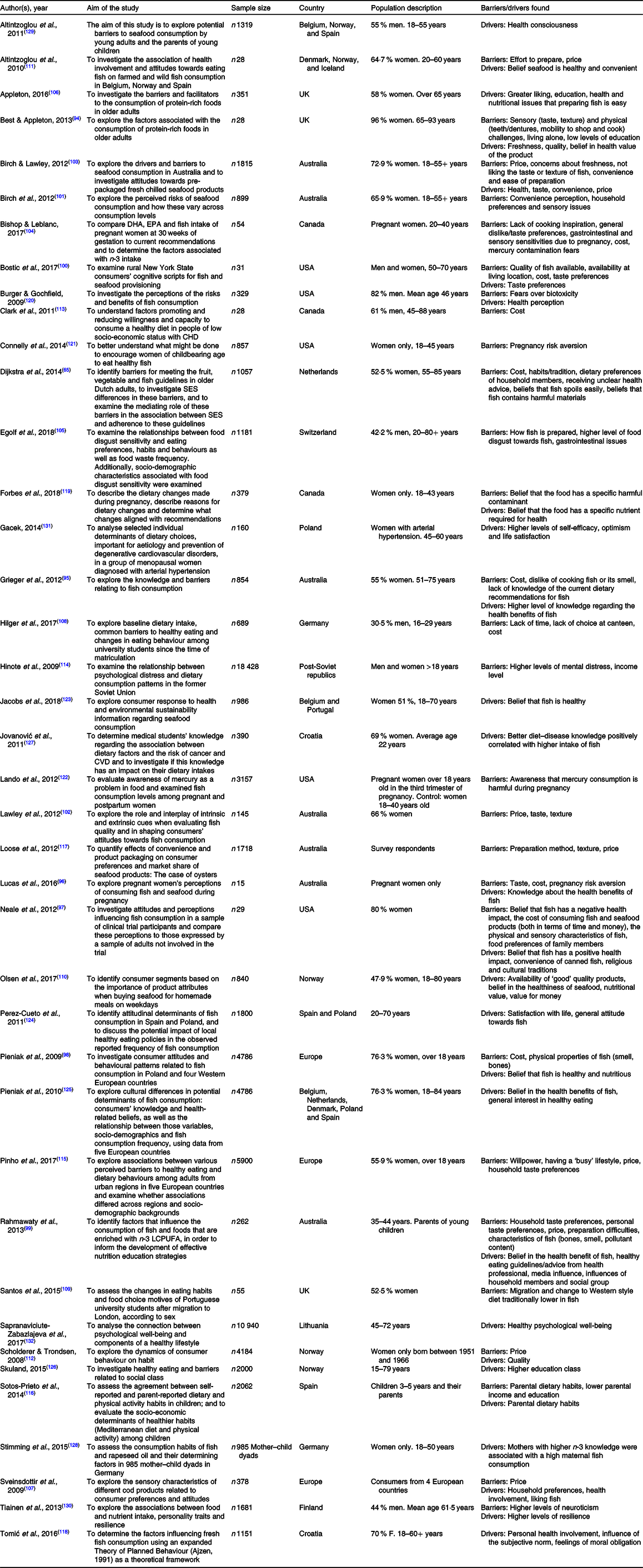

Age

Fifty-four papers explored the association between seafood consumption and age. There was a positive association between older age and seafood consumption in forty-three of these papers(Reference Buscemi, Nicolucci and Lucisano12–Reference Li, Xun and Zamora53). The largest study to find this was Patel et al.(Reference Torris, Smastuen and Molin39) which analysed 21 984 participants’ seafood intake. A smaller number of studies (n 5) noted a positive association between seafood consumption and younger age group(Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54–Reference van Woudenbergh, van Ballegooijen and Kuijsten58); however, these studies all had a sample population of over 50 years of age, their interpretation of young age was relative only to their specific study cohort.

Sex

Thirty-one papers explored the association between seafood consumption and sex. Overall, there was not a strong directional association between sex and seafood consumption observed. Seafood consumption was higher in men than in women in thirteen papers(Reference Akbaraly and Brunner13,Reference Hostenkamp and Sørensen16,Reference Jahns, Raatz and Johnson18,Reference Marushka, Batal and Sadik22,Reference Touvier, Kesse-Guyot and Mejean29,Reference Christensen, Raymond and Blackowicz31,Reference Kim, Xun and Iribarren52–Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54,Reference Giuli, Papa and Mocchegiani59–Reference Lake, Adamson and Craigie62) as opposed to eleven papers(Reference Akbaraly and Brunner13,Reference Monastero, Karimi and Silbernagel24,Reference Clonan, Holdsworth and Swift32,Reference Patel, Sharp and Luben34,Reference Nahab, Pearson and Frankel37,Reference Langlois and Ratnayake40,Reference Belle, Wengenroth and Weiss51,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54–Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63) finding that women were more likely to consume seafood. Two of these studies found that men are more likely to consume fried fish(Reference Akbaraly and Brunner13,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54) , and according to three studies, women were more likely to consume non-fried fish(Reference Akbaraly and Brunner13,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63) . For a number of papers, no association between fish consumption and sex was identified(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14,Reference Kossioni and Bellou19,Reference Crowe, Skeaff and Green47,Reference van Woudenbergh, van Ballegooijen and Kuijsten58,Reference Chung, Nettleton and Lemaitre64–Reference Alkerwi, Sauvageot and Buckley68) . When considering intakes by sex, it is important to consider adjustments for energy intake in the analysis. The following papers adjusted for energy intake(Reference Mohanty, Siscovick and Williams23,Reference Strøm, Halldorsson and Mortensen27,Reference Wallin, Di Giuseppe and Orsini28,Reference Stravik, Jonsson and Hartvigsson30,Reference Zamora-Ros, Castañeda and Rinaldi36,Reference Brasky, Neuhouser and Cohn38,Reference Karlsson, Rosendahl-Riise and Dierkes43,Reference Kim, Xun and Iribarren52–Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference Sala-Vila, Harris and Cofán67) , with the remaining studies not adjusting for energy intake, or not reporting adjustment.

Affluence

The majority of papers (twenty-one out of twenty-nine) that explored correlations between affluence and seafood intake found that seafood consumption had a positive association with higher socio-economic status, higher income or higher employment level. One paper saw a positive association between seafood consumption and lower socio-economic status status, income or employment level; however, this was associated with fried fish intake specifically(Reference Miura, Giskes and Turrell69). There was no association between these variables according to seven papers(Reference Buscemi, Nicolucci and Lucisano12,Reference Monastero, Karimi and Silbernagel24,Reference Christensen, Raymond and Blackowicz31,Reference Clonan, Holdsworth and Swift32,Reference Gaskins, Sundaram and Buck Louis44,Reference Giuli, Papa and Mocchegiani59,Reference Mendez, Plana and Guxens70) . The most common association found was between higher income and seafood consumption(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14,Reference Jahns, Raatz and Johnson18,Reference Razzaghi and Tinker26,Reference Nahab, Pearson and Frankel37,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63–Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer65,Reference Maguire and Monsivais71–Reference Nair, Jordan and Watkins75) . Significant associations were also seen between seafood consumption and higher socio-economic status(Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference Seiluri, Lahelma and Rahkonen76–Reference Watt, Carson and Lawlor79) as well as higher grade employment(Reference Akbaraly and Brunner13,Reference Strøm, Halldorsson and Mortensen27,Reference Touvier, Kesse-Guyot and Mejean29,Reference Gale, Robinson and Godfrey41) .

Education

Thirty-six papers found a significant association between education and seafood consumption. Most of these studies highlighted a positive association between education level and seafood consumption(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14–Reference Hostenkamp and Sørensen16,Reference Jahns, Raatz and Johnson18,Reference Mohanty, Siscovick and Williams23,Reference Razzaghi and Tinker26–Reference Stravik, Jonsson and Hartvigsson30,Reference Zamora-Ros, Castañeda and Rinaldi36–Reference Torris, Smastuen and Molin39,Reference Gale, Robinson and Godfrey41,Reference Lee, Howard and Mete42,Reference Burger45,Reference Pfeiler and Egloff46,Reference Belle, Wengenroth and Weiss51–Reference Mozaffarian, Stein and Prineas55,Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57–Reference Giuli, Papa and Mocchegiani59,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63,Reference Chung, Nettleton and Lemaitre64,Reference Maguire and Monsivais71,Reference Li, Dai and Ekperi73,Reference Larsson, Virtamo and Wolk80–Reference Wennberg, Tornevi and Johansson84) . An association between higher education and non-fried fish consumption, as well as an association between lower education level and fried fish consumption, was reported in two papers(Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54,Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57) . Whilst the majority of papers did find a positive association, Karlsson et al.(Reference Karlsson, Rosendahl-Riise and Dierkes43) and Hansen-Krone et al.(Reference Hansen-Krone, Enga and Südduth-Klinger33) both found that a higher percentage of people with lower fish intake had higher education or a university degree compared with those in the highest quintile of fish intake. However, despite statistical significance, in Hansen-Krone et al.’s(Reference Hansen-Krone, Enga and Südduth-Klinger33) study, the second highest percentage of people in higher education was seen in those who consumed fish 2–2·9 times/week. There was no significant association found between seafood intake and education in thirteen studies(Reference Buscemi, Nicolucci and Lucisano12,Reference Kossioni and Bellou19,Reference Levitan, Wolk and Mittleman21,Reference Marushka, Batal and Sadik22,Reference Monastero, Karimi and Silbernagel24,Reference Christensen, Raymond and Blackowicz31,Reference Patel, Sharp and Luben34,Reference Gaskins, Sundaram and Buck Louis44,Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer65,Reference Alkerwi, Sauvageot and Buckley68,Reference Mendez, Plana and Guxens70,Reference Haraldsdottir, Steingrimsdottir and Valdimarsdottir85) .

BMI

There was no clear association between BMI and seafood consumption with results varying greatly between studies. While thirty-four papers explored the association between BMI range and seafood intake, there was a correlation between higher fish intake and lower BMI in six of these papers(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14,Reference Mohanty, Siscovick and Williams23,Reference Langlois and Ratnayake40,Reference Belle, Wengenroth and Weiss51,Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63) . Two papers found an association between higher BMI and lower seafood intake(Reference Strøm, Halldorsson and Mortensen27,Reference Christensen, Raymond and Blackowicz31) . An association was seen between higher fish intake and higher BMI in eleven papers(Reference Larsson and Wolk20–Reference Marushka, Batal and Sadik22,Reference Patel, Sharp and Luben34,Reference Zamora-Ros, Castañeda and Rinaldi36,Reference Karlsson, Rosendahl-Riise and Dierkes43,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54,Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57,Reference Alkerwi, Sauvageot and Buckley68,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Chiuve86,Reference Rosendahl-Riise, Sulo and Karlsson87) . Three of these papers(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Chiuve86) stated that this association was with fried fish intake specifically. Fifteen papers found no association(Reference Heppe, Steegers and Timmermans15,Reference Kossioni and Bellou19,Reference Wallin, Di Giuseppe and Orsini28,Reference Hansen-Krone, Enga and Südduth-Klinger33,Reference Nahab, Pearson and Frankel37,Reference Gaskins, Sundaram and Buck Louis44,Reference Kim, Xun and Iribarren52,Reference Mozaffarian, Stein and Prineas55,Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference van Woudenbergh, van Ballegooijen and Kuijsten58,Reference Meier, Berchtold and Akré66,Reference Mendez, Plana and Guxens70,Reference Haraldsdottir, Steingrimsdottir and Valdimarsdottir85,Reference Chavarro, Stampfer and Hall88,Reference Song, Chan and Fuchs89) .

Smoking

Seafood consumption was positively associated with smoking in five papers(Reference Patel, Sharp and Luben34,Reference Zamora-Ros, Castañeda and Rinaldi36,Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Chiuve86) . Belin et al. (Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57) specified that this association was with fried fish intake. Strøm et al. (Reference Strøm, Halldorsson and Mortensen27) found that women who consumed less fish were more likely to be smokers. High fish intake was associated with former or non-smoking in twenty-seven studies(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14,Reference Heppe, Steegers and Timmermans15,Reference Levitan, Wolk and Mittleman21,Reference Marushka, Batal and Sadik22,Reference Patel, Sharp and Luben34,Reference Nahab, Pearson and Frankel37–Reference Lee, Howard and Mete42,Reference Belle, Wengenroth and Weiss51,Reference Kim, Xun and Iribarren52,Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Cauley54,Reference Mozaffarian, Stein and Prineas55,Reference van Woudenbergh, van Ballegooijen and Kuijsten58,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63,Reference Sala-Vila, Harris and Cofán67,Reference Li, Dai and Ekperi73,Reference Slagter, Corpeleijn and van der Klauw83,Reference Wennberg, Tornevi and Johansson84,Reference Chavarro, Stampfer and Hall88–Reference Karlsson, Strand and Dierkes93) . Eleven papers did not find an association between fish intake and smoking(Reference Buscemi, Nicolucci and Lucisano12,Reference Kossioni and Bellou19,Reference Larsson and Wolk20,Reference Mohanty, Siscovick and Williams23,Reference Wallin, Di Giuseppe and Orsini28,Reference Hansen-Krone, Enga and Südduth-Klinger33,Reference Karlsson, Rosendahl-Riise and Dierkes43,Reference Chung, Nettleton and Lemaitre64,Reference Alkerwi, Sauvageot and Buckley68,Reference Mendez, Plana and Guxens70,Reference Rosendahl-Riise, Sulo and Karlsson87) .

Physical activity

Twenty-nine studies included in this review explored associations between seafood consumption and physical activity level. Most studies (n 22) found that higher seafood intake was associated with higher engagement in physical activity(Reference Hostenkamp and Sørensen16,Reference Larsson and Wolk20,Reference Marushka, Batal and Sadik22,Reference Strøm, Halldorsson and Mortensen27,Reference Hansen-Krone, Enga and Südduth-Klinger33,Reference Zamora-Ros, Castañeda and Rinaldi36–Reference Torris, Smastuen and Molin39,Reference Belle, Wengenroth and Weiss51,Reference Kim, Xun and Iribarren52,Reference Bonaccio, Ruggiero and Di Castelnuovo56,Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63,Reference Chung, Nettleton and Lemaitre64,Reference Sala-Vila, Harris and Cofán67,Reference Wennberg, Tornevi and Johansson84–Reference Virtanen, Mozaffarian and Chiuve86,Reference Chavarro, Stampfer and Hall88–Reference Varraso, Barr and Willett90) . Three of these studies found a significant association between physical activity level and non-fried fish consumption specifically(Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57,Reference He, Liu and Daviglus63,Reference Chung, Nettleton and Lemaitre64) . Belin et al.(Reference Belin, Greenland and Martin57) also found a correlation between fried fish consumption and lower physical activity levels in adults. A correlation between higher non-fried fish intake and low physical activity was observed in one paper(Reference Anderson, Nettleton and Herrington14).

Influences on seafood consumption

Thirty-seven studies examined participant reported influences on seafood consumption (Table 1). Twenty of these reported on barriers to the consumption of seafood and twenty reported on drivers of consumption of seafood, with ten papers reporting on both. Studies were conducted in the USA (n 5), Europe (n 22), Canada (n 3) and Australia (n 7). All studies had a cross-sectional design. The selected studies identified some major influences on seafood consumption, most of which have both positive and negative aspects and can thus function as both drivers and barriers (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Number of papers examining the association between the demographic and social characteristics of seafood consumption.

Sensory and taste preferences

Sensory and taste preferences were named as barriers to seafood consumption in fourteen studies. Seven of these papers specified that the barriers to fish consumption were to do with fish characteristics such as taste, smell or presence of bones(Reference Best and Appleton94–Reference Birch and Lawley103). Within elderly, problems with dentition were highlighted as a barrier to consumption, as it was reported to impact on one’s ability to chew and bite(Reference Best and Appleton94). Gastro-intestinal issues following consumption of seafood also presented a barrier for some(Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Egolf, Siegrist and Hartmann105) . Unsurprisingly, a greater liking of the taste of fish was reported to drive consumption of fish(Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Appleton106,Reference Sveinsdottir, Martinsdottir and Green-Petersen107) .

Cost, convenience and availability

According to three studies(Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108,Reference Santos, Vilela and Padrao109) , residing in locations with poor availability of seafood or fish presented a barrier to its consumption. For example, Hilger et al. (Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108) explored barriers to healthy eating specifically in college students and found that lack of availability or lack of choice of fish and seafood in the canteen was a barrier to consumption of these products for students. Santos et al. (Reference Santos, Vilela and Padrao109) also looked at eating habits of university students; however, this sample size only focused on Portuguese students post-migration to the UK. This paper noted that migration to a country with lower reported fish consumption caused a significant decrease in these student’s fish consumption. Lack of access and availability were also noted in elderly cohort, where the impact of physical impairments such as reduced mobility or disability was highlighted as a barrier to the consumption for elderly people(Reference Best and Appleton94). Convenience in relation to preparing and consuming seafood was also highlighted as a barrier in five studies(Reference Best and Appleton94,Reference Birch, Lawley and Hamblin101,Reference Birch and Lawley103,Reference Olsen, Tuu and Grunert110,Reference Altintzoglou, Birch Hansen and Valsdottir111) .

In addition, a lack of ‘good quality’ seafood was also reported as a barrier to its purchase and consumption(Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Birch, Lawley and Hamblin101,Reference Scholderer and Trondsen112) . Living in a location where fresh and ‘good quality’ seafood was available positively influenced people to consume it, which was reported in two papers(Reference Best and Appleton94,Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100) . Cost of seafood was a commonly reported barrier to consumption and was mentioned in nineteen studies(Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer65,Reference Grieger, Miller and Cobiac95–Reference Lawley, Birch and Hamblin102,Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Sveinsdottir, Martinsdottir and Green-Petersen107,Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108,Reference Altintzoglou, Birch Hansen and Valsdottir111–Reference Loose, Peschel and Grebitus117) . Sotos-Prieto et al. (Reference Sotos-Prieto, Santos-Beneit and Pocock116) specified that those with low income were less likely to consume fish regularly. However, three papers found that providing good value for money (i.e. special offers in stores) had a positive influence on seafood consumption(Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Olsen, Tuu and Grunert110,Reference Scholderer and Trondsen112) .

Knowledge of storage, handling and cooking

Three studies highlighted that lack of skills, particularly cooking skills, can be barriers to seafood consumption(Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99,Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Altintzoglou, Birch Hansen and Valsdottir111) . Bishop & Leblanc(Reference Bishop and Leblanc104) and Rahmawaty et al. (Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99) reported that people who lacked cooking knowledge and inspiration found it difficult to find the motivation to cook seafood for themselves and their household. Dijkstra et al. (Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer65) also found that holding the belief that fish spoils easily is a barrier to its consumption. Believing that fish is a convenient food and is easy to prepare was highlighted as a positive influence on its consumption in two studies(Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97,Reference Appleton106) .

Familial, lifestyle and cultural environment

Six studies(Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer65,Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97,Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99,Reference Sveinsdottir, Martinsdottir and Green-Petersen107,Reference Pinho, Mackenbach and Charreire115,Reference Sotos-Prieto, Santos-Beneit and Pocock116) found that the dietary preferences of household members were an influence to seafood consumption. Low- or non-fish consumers were more likely to view the taste preferences of household members as a negative influence on frequency of seafood consumption(Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99). A busy lifestyle was also noted as a barrier by Pinho et al.(Reference Pinho, Mackenbach and Charreire115). Four papers found various environmental influences can drive seafood consumption. Neale et al. (Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97) stated that religious and cultural traditions, as well as parental attitudes, can be positive influences on seafood consumption if they encourage the same. Participants in Rahmawaty’s et al.(Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99) study mentioned that professionals, media, household and society can be positive influences on their seafood consumption. Parental dietary habits strongly influence seafood consumption in their children(Reference Sotos-Prieto, Santos-Beneit and Pocock116). Subjective norm and feelings of moral obligation can also positively influence seafood consumption; therefore, this can act as both a barrier and a driver of seafood consumption depending on the situation(Reference Tomić, Matulić and Jelić118).

Health and nutritional beliefs

Holding certain health and nutritional beliefs about seafood can influence whether or not the person chooses to consume seafood. For example, the perception that fish and seafood may contain harmful contaminants was seen as a barrier in five papers(Reference Dijkstra, Neter and Brouwer65,Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97,Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Forbes, Graham and Berglund119,Reference Burger and Gochfeld120) . Three papers(Reference Lucas, Starling and McMahon96,Reference Connelly, Lauber and Niederdeppe121,Reference Lando, Fein and Choinière122) found avoidance of fish, due to the belief that it is harmful, was a common barrier during pregnancy. Perceiving seafood to have a high ‘health’ value, or believing it contains certain nutrients needed for good health, is a commonly reported positive driver of its consumption(Reference Best and Appleton94–Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99,Reference Birch, Lawley and Hamblin101,Reference Sveinsdottir, Martinsdottir and Green-Petersen107,Reference Olsen, Tuu and Grunert110,Reference Altintzoglou, Birch Hansen and Valsdottir111,Reference Loose, Peschel and Grebitus117–Reference Burger and Gochfeld120,Reference Jacobs, Sioen and Marques123–Reference Altintzoglou, Vanhonacker and Verbeke129) .

Psychological traits

A small number of papers (n 3) found that having certain psychological traits may present barriers to consuming seafood. Having high levels of distress(Reference Hinote, Cockerham and Abbott114) and neuroticism(Reference Tiainen, Männistö and Lahti130), and low willpower(Reference Pinho, Mackenbach and Charreire115) were highlighted as possible barriers to seafood consumption. Four papers explored the influence of various psychological states and personality traits on seafood consumption and noted that having high levels of self-efficacy, optimism, life satisfaction, resilience and a general healthy psychological well-being positively influenced seafood consumption(Reference Perez-Cueto, Pieniak and Verbeke124,Reference Tiainen, Männistö and Lahti130–Reference Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva, Luksiene and Virviciute132) .

Discussion

The results of this systematic review highlight that seafood consumers were more likely to be older, more affluent (in terms of income, employment level and/or socio-economic status), educated and physically active and were less likely to smoke compared with non-seafood consumers. Sex and BMI did not appear to have a clear influence on seafood consumption. The findings also suggest that the most commonly reported influences on seafood consumption relate to personal preference, availability, cost, cooking skills and knowledge, environment, health and nutritional beliefs and psychological traits. The most commonly reported barrier to seafood consumption was price. Other barriers included the sensory or physical characteristics of seafood, household preferences, health and nutritional beliefs (e.g. that fish contains harmful contaminants), environmental barriers, lack of cooking skills and negative psychological states/personality traits. The most commonly reported drivers of seafood consumption were perceived health benefits of seafood, environmental influences (e.g. family, friends and social norm), availability of fresh seafood, positive psychological states or personality traits and personal preferences. These barriers and drivers agree with certain common characteristics that seafood consumers seem to share.

Cost was the most commonly reported barrier to seafood consumption(Reference Grieger, Miller and Cobiac95–Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108,Reference Pinho, Mackenbach and Charreire115,Reference Dijkstra, Neter and van Stralen133) . This is a particularly important barrier for people who have a lower income level(Reference Hinote, Cockerham and Abbott114,Reference Sotos-Prieto, Santos-Beneit and Pocock116) . Food prices play a major role in diet quality and food choice(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski77). Although seafood has become more widely available, depending on the country, the fish species, and the presentation or format of sale, it can be a costly item compared with other high protein foods(134,135) . This is in line with our findings, as those who consumed the highest amounts of seafood tended to have higher incomes, as well as be of older age, which agrees with the general trend of income increasing with age as a person gain experience over time(Reference York136). In addition, as individuals age, increased risk of health issues such as cognitive decline and CVD can influence food choice, including that of seafood, known to be rich in nutrients beneficial to health(137,138) , with the perceived cost benefit changing as one ages. Unsurprisingly, cost was also highlighted as a barrier to healthy eating for university students(Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108). Interventions carried out in the UK(Reference Burr, Trembeth and Jones139) and the USA(Reference Oken, Guthrie and Bloomingdale140) which trialled providing vouchers for the purchase of healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables or seafood, have been found to be a simple and effective way of encouraging people to purchase these products. Interestingly, the provision of these vouchers was more effective than dietary advice alone. Other reviews found that pricing interventions generally increased the consumption and purchase of promoted foods(Reference Gittelsohn, Trude and Kim141–Reference Wall, Mhurchu and Blakely143).

Our findings suggest that those who achieve a higher level of education are more likely to be seafood consumers. Having a higher degree of education may result in better knowledge and understanding of current healthy eating recommendations for fish(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski77,Reference Mertens, Kuijsten and Dofková144) . Education may also be associated with increased nutritional knowledge in general and the ability to translate this knowledge into healthy dietary practice(Reference Hiza, Casavale and Guenther145). However, education level does not directly determine level of seafood consumption as evidenced by population groups that eat fish traditionally, but have generally low rates of formal education(Reference Mohan Dey, Rab and Paraguas146). Belief that fish is healthy and contains important nutrients for health is often reported as a major influence on seafood consumption, regardless of education level(Reference Best and Appleton94–Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99,Reference Olsen, Tuu and Grunert110,Reference Tomić, Matulić and Jelić118,Reference Forbes, Graham and Berglund119,Reference Jacobs, Sioen and Marques123–Reference Pieniak, Verbeke and Scholderer125) . The most commonly reported barrier was the belief that fish or seafood may contain harmful contaminants(Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97,Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99,Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Forbes, Graham and Berglund119,Reference Dijkstra, Neter and van Stralen133) or that fish/seafood is harmful during pregnancy, with particular concern about its mercury content(Reference Lucas, Starling and McMahon96,Reference Connelly, Lauber and Niederdeppe121,Reference Lando, Fein and Choinière122) . Education regarding true contamination levels in various fish and seafood species, as well as guidelines for fish consumption during pregnancy, may be paramount to overcoming these barriers, and information received from healthcare professionals need to be clear(Reference Dijkstra, Neter and van Stralen133). Those who are in greater agreement that fish should be fresh, that it is easy to prepare, is convenient and disagreement that fish spoils easily are more likely to consume it(Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97,Reference Appleton106) . However, interventions aiming to improve diet quality or intakes of certain food groups through nutrition education alone have had mixed results, suggesting a combination of methods including education may be needed to improve diets(Reference Jacobs, Sioen and Marques123,Reference Ha and Caine-Bish147–Reference Manios, Moschonis and Katsaroli152) .

Gaining knowledge about the health benefits of seafood may help overcome barriers such as nutritional and health beliefs, or habits arising from an individual’s Familial, Lifestyle and Cultural Environment. However, it is also important to know that may be less effective in overcoming barriers such as taste. Having a dislike of the taste and/or smell of fish(Reference Best and Appleton94–Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Bishop and Leblanc104) , as well as a dislike of its texture, is a commonly reported barrier to seafood consumption in general(Reference Neale, Nolan-Clark and Probst97,Reference Pieniak, Verbeke and Brunso98) . In particular, pregnant women seem to have a high level of food disgust or gastrointestinal issues related to seafood consumption(Reference Bishop and Leblanc104,Reference Egolf, Siegrist and Hartmann105) . Changes that come with old age, such as chemosensory loss, can lead to reduced enjoyment of the taste of seafood(Reference Best and Appleton94). Physical impairments that reduce the convenience of cooking or purchasing foods present an important barrier to seafood consumption in the elderly(Reference Best and Appleton94,Reference Rahmawaty, Charlton and Lyons-Wall99) . Some of these barriers are personal preferences and therefore are difficult to overcome; however, in regards to taste changes, adding natural food flavours has been used in an attempt to increase food and nutrient intakes in the elderly with some success(Reference Henry, Woo and Lightowler153). Previous research has also shown that participants who disliked the taste of fish or seafood, but who were aware of its health benefits, attempted to overcome this taste preference barriers by experimenting with various cooking methods and seafood products(Reference Lucas, Starling and McMahon96). However, knowing the benefits of seafood alone may not be enough to initiate its purchase and consumption due to time constraints for cooking as well as affordability(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski77). Physical impairments to cooking and food shopping may be overcome by organising meal delivery to the persons home, which have been shown to increase diet quality and nutrient intakes among the elderly(Reference Zhu and An154,Reference Roy and Payette155) . However, this may not be appropriate for everyone, such as patients with behavioural and cognitive impairments(Reference Young, Binns and Greenwood156).

Good local availability of fresh, or what consumers deem good quality seafood, or lack thereof, seems to influence intent to purchase what actually is on offer(Reference Best and Appleton94,Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108,Reference Santos, Vilela and Padrao109) . Availability of seafood in an individual’s living location, or where they tend to purchase their meals, influences whether or not they consume it(Reference Bostic, Sobal and Bisogni100,Reference Hilger, Loerbroks and Diehl108,Reference Santos, Vilela and Padrao109) . The purchasing behaviour can concern overall availability of seafood in general but may also be influenced by the type of seafood available. According to Bord Bia(135), fish represented 2 % of the Irish grocery spent in 2018 and the large majority of this was fresh fish. Frozen fish sales decreased compared with previous years, partially due to a decrease in shoppers’ willingness to buy frozen fish. This seems to highlight a preference for fresh fish over frozen. Therefore, if fresh fish is not available, the consumption of seafood may decrease due to the consumer’s unwillingness to purchase frozen alternatives that are available. Food availability is also related to affluence(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski77). Analyses show that supermarkets tend to cluster in more affluent areas and that ‘food deserts’ are common within lower socio-economic status neighbourhoods(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski77). Studies have also shown that residing in lower-income neighbourhoods has been associated with lower consumption of fish(Reference Diez-Roux, Nieto and Caulfield157) and that a person’s level of income and occupation is a significant determinant of fish consumption(Reference Bakre, Song and Clifford158).

This study has identified multiple barriers to seafood consumption which need to be overcome in order to increase seafood intake. Methods to help people overcome these barriers include pricing interventions, such as the provision of food vouchers or in-store discounts or value offers(Reference Burr, Trembeth and Jones139–Reference Wall, Mhurchu and Blakely143). In addition to this, interventions may need to focus on increasing nutritional knowledge and awareness through school-based(Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Van Cauwenberghe and Spittaels151) and adult(Reference Sahyoun, Pratt and Anderson159) educational programmes as well as environmental sustainability education(Reference Jacobs, Sioen and Marques123). However, the most promising results are seen when interventions tackle multiple or most of the aforementioned barriers to consumption(Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner150,Reference Sahyoun, Pratt and Anderson159) . This means combining individual education (which should combine nutrition theory and practice, i.e. cooking skills) from school level through to senior years with structural environmental changes, such as improving access to supermarkets(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski77) and making healthy foods such as seafood more affordable(Reference Burr, Trembeth and Jones139), particularly for people on lower incomes. Future interventions aiming to increase seafood consumption, or diet quality overall, should therefore take on a multi-faceted approach, as seen in the Community Intervention to Increase Seafood Consumption Project carried out in Australia(Reference McManus, White and Newton160). Any interventions seeking to promote seafood consumption should be carried out with consideration of biotoxicity risk(Reference Sirot, Leblanc and Margaritis6,Reference Hellberg, DeWitt and Morrissey7) . In addition, recommendations should also take into account sustainability targets, such as those set out in the EAT-Lancet report which recommend a maximum of about 100 g of fish/d(Reference Willett, Rockstrom and Loken5).

Limitations

It is important to note that, in cross-sectional studies, any solitary associations are not evidence of causality. The determinants of food choice are complex and cannot be attributed to only one single reason. Overall, conclusions should be drawn with caution owing to the small number of studies for each specific influence–intake association. Limitations of this study include that the findings of this review are limited to published papers only (unpublished results or additional reports were not included), in English, between 2008 and 2019. This is also one of the first systematic reviews published on the determinants of seafood consumption. Although it is a systematic review, meta-analysis was not carried out; therefore, sample size was not considered. Additionally, categorisation of findings was subjective however was decided on once consensus that was reached among authors following discussion.

Conclusions

This review has highlighted two key aspects of importance for the development of effective public health campaigns aiming to increase consumption of seafood. It firstly determined demographic factors influencing consumption of seafood, thus outlining which population groups could be targeted. It then secondly outlined evidence of the reported reasons influencing seafood consumption, outlining areas for potential intervention including nutritional education, development of cooking skills, pricing and availability amongst others. The evidence presented demonstrates that specific population groups such as those of a younger age and those less educated would benefit most from interventions, information which would allow the development of targeted and appropriately designed interventions, which could focus on aspects specifically influencing intakes in each of these population groups. More research is needed to explore the effectiveness of specific interventions in increasing the consumption of seafood.

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the Irish Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine (DAFM). Funding Agency reference no. 17/F/264.

Substantial contribution to the conception and design of this paper: S. G., E. R. G. and C. M. T. Substantial contribution to the acquisition of data: S. G. and S. L. Substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data: S. G., S. L., E. R. G. and C. M. T. Drafting the article: S. G., S. L., E. R. G., C. M. T. and F. B. Critically revising the article: F. B., X. W., E. R. G. and C. M. T. Final approval of the version to be published: E. R. G. and C. M. T.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520003773