Growing up, I never knew how to answer questions about where I was from. I couldn’t very well say, I’m from a dusty industrial township that I never want to see again. For the sake of convenience, I said, Lucknow. It was the city where we spent vacations, with family, but we don’t have roots there.

Mom says our roots lie in Muhammadabad Gohna, a mofussil kasba, a village struggling to turn into a town. It used to be part of Azamgarh district once and is now in a new district called Mau. A few kilometres away is the village of Karhan, my grandfather’s nanihāl (maternal ancestral home). We can trace back fourteen generations here. The uncle who told me this is now gone. Fifteen generations, then.

We are obvious misfits here. The women of the family rarely step outside for grocery, errands, or jobs. A new generation of girls does go to college, but they wear hijabs and burqas.

I fight with my mother: We don’t come from this! You came from cities like Lucknow and Delhi, from secularism and cosmopolitanism, from an English-medium education. You wore breeches and rode horses!

Mom counters: Daddy said never to forget our roots. Over all protest, she builds a morsel-sized house there. Within the walls of a large ancestral house, several branches of the family have built individual units. It wears a deserted look around the year, but comes alive during the month of Moharram. Shia families across the state return to ancestral homes, especially for the first ten days, to mark the tragedy within which all tragedies are meant to be subsumed – the martyrdom of Imam Hussain and the slaughter and devastation that visited his clan in Karbala. Individual grief is folded into an unending sorrow that connects you to the community.

The explanation given to me for why Grandpa so rarely visited was that it lacked the good hospitals his fragile heart needed. He was a poet and a scholar who researched the literature associated with our mourning traditions, but he didn’t bring his own children home for Moharram.

I argue with Mom: I do not recall Grandpa saying that we belong to Muhammadabad. What he did say was that there were only two things Azamgarh was known for. The first was imarti, a deep-fried tightly coiled whorl of flour, soaked in sugar syrup. The second was goondagardi. Goondaism.

Goonda is an Indian-English word. This is not necessarily a professional gangster, but someone liable to attack or intimidate people. The Uttar Pradesh Control of Goondas Act (1970) describes a goonda as a habitual offender in matters of public obscenity or causing disharmony between communities (religious, linguistic, racial, caste and so on), illegal possession of arms, a gambler, a tout, a house-grabber, or someone ‘reputed to be a person who is desperate and dangerous to the community’.

I was too young to ask my grandfather what it meant to belong to a place that’s rich in sugarcane, poetry and goondas. By the time I began to wonder, he was gone. It was left to me to sift through words, memories and the land itself for answers.

*

I visited Muhammadabad Gohna and Karhan a few times, partly to appease Mom and partly out of curiosity.

It’s true about the imarti. Row upon row of imartis line the sweet shops. Coils of pure sugar shock. In winter, you see mounds of gur (jaggery) sold by the kilo off handcarts.

There’s a railway station, too short for the long trains that come through. Once, my mother failed to disembark because the compartment she was in was so far out on the railway track that the platform wasn’t even visible. Peering out of the window, she assumed the train had halted in the middle of nowhere. When I heard, I bit my tongue and stopped myself from saying what I was thinking: it is the middle of nowhere.

It certainly isn’t the sort of place where you can call an Uber. I’ve begun to step out nevertheless, unaccompanied by menfolk and uncaring of tradition. I neither wear a burqa nor the ‘Syed’ prefix, used by families to indicate descent from the Prophet Muhammad. Yet, tradition follows me wherever I go.

One day, I decided to brave a bone-rattling journey to visit a library in another village. Four modes of transport – a cycle rickshaw, an auto-rickshaw, a bus, a car – were needed to cover a distance of about thirty odd kilometres. Sixteen adults, each of them in better humour than me, were packed into a modified auto-rickshaw that was originally built to ferry four passengers. The village roads were so pitted, the only thing that prevented me from being violently jolted and tossed out of the vehicle was the fact that I was packed in so tight, mercifully between two other women, that movement was impossible.

The elderly woman on my right kept up a cheerful banter in a Bhojpuri dialect that was so far removed from Hindi, she may as well have been talking French. Finally, she asked where I came from. I caught the word ghar. Home.

I said, I’m from here, from Muhammadabad actually.

The elderly woman gave me a sideways stare. ‘From Syedwada?’

It wasn’t a question. One glance and she had me pinned to my street: Syedwada, a neighbourhood filled with Syed Muslim families, was stamped on my face, my accent, my clothes, my gestures, my obvious disconnect with the world outside home. Even without the veil, and despite my mixed blood inheritance, she could tell.

I didn’t bother to deny it. I didn’t ask how she could tell. I know my country enough by now to know how.

*

Rajeev Yadav is a human rights activist from the same approximate region, what used to be the undivided Azamgarh. Unlike me, he grew up there. When I put to him the puzzle of what my grandfather said – about imarti and goondagardi – he came back with: ‘You must be Savarn Muslim.’

Sa-varn. Upper caste. I was taken aback at first. Of course, a sort of caste system does exist among Muslims, and Sikhs and Christians. Still, that my family’s worldview could be coloured by caste was not a thought I’d entertained. I should have known better. Muslims in the eastern districts have always been highly stratified with Syeds, Shaikhs, Raqis (people who claimed to be Iraqis who migrated a couple of centuries ago) and Mohammadan Rajputs identifying as distinct communities. Like their Hindu counterpart, ‘Musalman castes’ were also identified by profession in pre-independence censuses: Darzis, Qasabs, Telis, Bhangis, Dhobis, Mughals, Bhat, Kuneras, Dafalis, Kunjras, Nats.1

I’d heard that certain castes, who had very small landholdings of their own, served as the lath-baaz (stick wielders) for bigger landlords. I turned to another Azamgarh native and human rights activist, Naseeruddin Sanjari, to ask what was implied by that. He pointed out that landlords in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries had been more or less reduced to being revenue collectors for the British government. They maintained pehelwans (wrestlers) and lath-baaz to serve as guards, or to help collect revenue from peasants. Besides, the stick was wielded to make sure everyone treated landlords with the respect to which they felt entitled. The landlords were thus one step removed from the physical enactment of aggression.

Land was the main identity. Bigger landlords had civil relationships with each other across religious lines, and were often upper caste. The outcastes, Dalits, rarely owned land. Scholars have noted that eastern Uttar Pradesh remained semi-feudal well into the 1990s, with 72 per cent of workers dependent on farming. Roger Jeffery and Jens Lerche have observed that the lack of social development was linked to the ‘uncompromising character of its upper class and upper caste elite’.2

In other words, the elites refused to relinquish control over land, refused to share power in ways that would fulfil the promise of democracy. This caused sharp imbalances between east and west within the same state. A 2005 study by the state’s planning department used twenty-nine development indicators and found that of the twenty most developed districts, fifteen were in the west, and of the least developed twenty districts, seventeen were in the east.3 Among the least developed districts were Azamgarh and Mau.

South of the Ghagra river, criss-crossed by a dozen smaller rivers with names that conjure distinct personalities, the land has been fertile for longer than anyone remembers. This is part of a civilisation that offers us the pithy phrase ‘jar, joru, jameen’ or ‘zar, zan, zameen’ – ‘gold, woman, land’ – the three things men fight over. Of these, land is the hardest to guard since it cannot be locked away. To guard the land, one needs other men, or guns. My mother told me of her surprise when she learnt that a gentle-mannered cousin was riding about his farm in Karhan with a gun. He explained, it was unavoidable. You had land, you guarded it. There was very little land left anyway. Grandpa had none. He used to have an old gun, though none of us ever saw it. His temperament can be judged by the story Mom tells about how he behaved when a snake entered the house. He pulled on a pair of thick leather shoes and called the cops.

My grandparents had quit the land. They didn’t live off farming. Very few could. The district gazetteer of 1922 – in the midst of my grandfather’s early childhood years – noted that, despite its fertility and suitable climate, Azamgarh barely produced enough food to feed itself. But did that make people violent?

Not especially. In 1922, the gazetteer also noted that ‘on the whole, crime is light’, going up only in times of famine. Offences against public tranquillity and trespass were common problems, though; landowners were ‘particularly tenacious of their rights and quick to resent any supposed or real encroachment’.

What happened to this fabled tenacity in our family? How did my grandfather let go so easily of his share of land?

I look for answers in his memoir, Gubār-e-Karvān (Dust left behind by a caravan), where he describes a jāgīrdārāna māhaul, the landlords’ environment. Up until the early twentieth century, landlords’ homes were like miniature fortresses, with gardens, stores, kitchens, kuchehri (entertainment hall), imāmbārās, cellars, stables, offices, double-storeyed living quarters. He also confirmed the tradition of begār. People cleaned, managed animals, cooked, worked hand-held fans, but what they were paid was given as reward for good service, not a wage they could demand as their right.

When he was 13, his father died and his link to the land started to weaken. A great-uncle took him away to Mahmudabad, a princely estate near Lucknow, for a modern education. Exciting cultural conversations were unfolding in campuses and newspaper offices at the time. Grandpa got entangled in student politics and fell in with the progressive writers’ movement. He began to write poems against imperialism, oppression and blind traditionalism. In the 1940s, revolution was not an empty idea. Many students were socialists and freedom fighters. Grandpa, too, was arrested and put in jail for a few months.

Later, he did return to practise law in Azamgarh and the neighbouring Ghazipur court. There was, however, little to keep him there. Azamgarh birthed many writers but few of them actually lived there. Grandpa, too, returned to Lucknow and its vibrant world of letters, and, from 1946 onwards, worked for the Indian government in various media and cultural roles. Transfers meant uprooting himself and his family every few years, but this didn’t seem to bother him. Perhaps he just liked living in cities. Perhaps he only cared about finding literary friends and doing the work he felt was his own to do.

There was no mention of brute violence in his memoir, though. What could have triggered his careless jibe about goondagardi?

*

Rajeev Yadav reminded me that the ruin of Azamgarh’s reputation can be traced to 1857. The rebels who first rode into Delhi, having mutinied against the British East India Company, were mainly Purbia: soldiers from the eastern districts who caused mayhem in Delhi. Plunder by soldiers was not new, of course, but 1857 was an enormously disruptive event and this absolute breakdown of order became linked with Purbias.

Azamgarh was a crucial site during the uprising. It was here that an Ishtehār (proclamation) was issued, perhaps by one of the grandsons of the last Mughal emperor. It sought to overthrow the English, who ‘had ruined each class of citizen – zamindaar, merchant, civil servants, soldiers, artisans and even the clergy’, but more interesting, it also served as a kind of pre-democratic manifesto, with promises that the restored Badshahi (royal) government would resolve the problems of each class.4

The aftermath was brutal. Thousands were executed, more exiled. It became harder for Purbias to find employment as soldiers. Many were forced into indentured labour in foreign colonies. There was a difference too in the way the British treated landlords and nobles of the eastern, central and western districts. The west gained from agricultural improvements like canals, less fragmented landholdings, less harsh taxes imposed on the actual tillers of the land. Meanwhile, the eastern landlords incurred mounting debts and allowed sub-tenanting; there was no significant investment by the government.

After India gained independence, the feudal system continued in all but name. Landowners no longer faced the same kind of oppressive revenues demanded by the British government, but they continued to extract wage-less labour. Hindi writer Shiv Prasad Singh set his landmark 1967 novel Alag Alag Vaitarni in a village in eastern Uttar Pradesh, describing complex caste equations where those who are higher up the ladder depend heavily on lower-caste labour, but behave as if they were doing the latter a favour. A character of the Chamar caste is beaten for refusing to work in the fields without a wage in the middle of a drought. Weeping, he contrasts his situation with that of a group of nomadic Chamars who do the same work, but with a measure of dignity: in refusing to put down roots, they can refuse to beg the upper castes for a bit of land to till or to build their huts. To him, they appear free as birds, and he reflects that the most fragile hut can turn into a shackle for people who do not own land.

After independence, there were some efforts at land distribution. There was a ceiling on how much land an individual could hold. Many landlords legally transferred lands to relatives or employees, but did not relinquish control. This probably required that a degree of fear be instilled in the hearts of those who were owners on paper, but dared not act as if they were.

The feudal lords of yore were also establishing new founts of power and wealth. They became politicians, contractors, real estate dealers. Sticks were eventually replaced with guns.

*

In the twenty-first century, vast swathes of north India have developed a reputation for goondaism. There are islands of exception: Lucknow especially had a reputation for refinement and extreme politesse, and, being the state capital, was easier monitored. But Uttar Pradesh has been described as a pit-stop to hell, and even as a failed state.5

Part of me rears up in defence. I want to say, this is unfair stereotyping. But there’s no getting away from the fact that the state tops the crime charts. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, some 3.06 million crimes were recorded under the Indian Penal Code in 2017, of which Uttar Pradesh accounted for the highest number: 310,084.6

I want to dodge, and point to more obfuscating data: Kerala is one of the least populated, best-educated states, but it has the highest crime rate in the country. Even Maharashtra and Rajasthan have higher crime rates than Uttar Pradesh. Trouble is, I know the crime rate is based on reportage, even of minor assaults and skirmishes, and can be indicative of public faith in the system or an unwillingness to be cowed down by goons. As a percentage of its population, Uttar Pradesh reports a crime rate only marginally higher than the tiny islands of Andaman and Nicobar, which are home to primitive tribes and where only 638 crimes have been reported. It just doesn’t add up. Chances are, someone has been fudging data.7 It is also likely that people are too scared to report crime, and things are probably worse than they look on paper.

One way to look at aggression is to look at guns. The risk of gang violence and intimidation is higher with more guns floating around. The legal firearm possession rate in 2016 was highest in Uttar Pradesh;8 it also records the highest number of violations of the Arms Act of 1959. There’s no accounting for the extent of illegal weapons, but there is a well-documented cottage industry in basic rifles and hand-held guns called desi katta or tamancha. Until a few years ago, it was possible to get one made for anything between 1,200 and 5,000 rupees (USD 17 and 70).

Guns have been manufactured by rural ironsmiths for centuries.9 The trade was above board and the clientele was mainly farmers or regional armies.10 However, since firearms have required licences, the trade has slipped into the grey market. A small, localised industry has grown into a cross-country trade. Some of the demand is driven by gangsters, but manufacturers have also suggested that police officials also acquire desi kattas, to plant on people they want to arrest.11 Police officials are not known for being sticklers for rules. This state also reports the highest number of custodial deaths and suspected ‘fake encounters’,12 wherein police personnel kill people in cold blood after abducting and assaulting them. Some of those killed are petty thieves and goons; some are merely suspected of crime; most are poor.

*

It wasn’t until I started asking around that I heard a similar stereotype about western Uttar Pradesh, that it was famous for two things: the sweetness of its cane juice, and its gang wars.13

Violence is certainly not limited to Azamgarh. In the national capital, Delhi, you might see notices at eateries advising patrons that firearms are not permitted. I have seen notices painted in buses in the neighbouring state, Madhya Pradesh, asking passengers not to carry loaded guns. If such warnings are any indication, then people do carry guns when they’re out for pizza or checking out the price of corn. What may be specific to the eastern districts is an intersection of feudal habits, joblessness and politicians working in tandem with business contractors.

There was a theory afoot in the 1970s and 1980s that economic development would help combat goondaism. The government’s policies had the opposite effect. Funds poured in by way of state-funded road construction and railway projects. Those who profited from aggression quickly got organised. Whoever had more weapons and money began to grab more contracts, and eventually made inroads into politics. The highway to the heart of power began to be laid with blood and bullets.

Still. It bothered me that Azamgarh had the worse reputation when there’s Gorakhpur right next door. Now that’s a district where local gangsters have been described as ‘a herd of Capones’.14 From Gorakhpur emerged Hari Shankar Tiwari, the first alleged gangster to win an election whilst lodged in prison. He won six elections straight, supported by various political parties, and was acquitted of all charges eventually.15 He and his arch rival Virendra Pratap Shahi, also from Gorakhpur, started out in the 1970s. Reports suggest that their early adventures were classic goondagardi: taking over land that belonged to someone else, refusing to pay for fuel at petrol pumps, abusing anyone who dared to look them straight in the eye. By the 1980s, both groups – Brahmin and Thakur – were running a sort of parallel administration. People were going to them rather than to the courts to resolve land disputes or other conflicts.16 From there to becoming actual administrators was one short step.

In the 1980s, elections were sometimes captured through intimidating voters and taking over booths. Once people saw that the judiciary and government appeared powerless to prevent such capture, they decided to transfer their mandate to whoever was able to get things done.

Raghuraj Singh, better known as Raja Bhaiyya (literally ‘king brother’), comes from minor royalty and was once described as the ‘Gunda (goon) of Kunda’ by a former chief minister, who later bestowed a ministerial berth upon the same man he had derided.17 In western Uttar Pradesh, there was Mangu Tyagi, who, as one cop put it, has been charged under ‘almost every section of the Indian Penal Code’ including murder, abduction, extortion, possession of illegal arms, arson and so on.18 That didn’t interfere with his nomination by a mainstream political party.

Dhananjay Singh, who has been described as ‘mafia-turned-politician’, didn’t even need political parties.19 He won as an independent candidate in 2002.

One of the most powerful men in the Azamgarh-Mau region is Mukhtar Ansari, who won Mau four times.20 Reports have described him as a sort of ‘Robinhood boss’, the man you went to if you needed money for your daughter’s wedding or a job for your son, or to keep the local textile industry up and running. He has been in jail too, accused of various crimes including murder and goondaism.

Such men are often described as bahubali (strongman), and their power can be gauged from the spectacular fashion in which they clash. When a politician known to have links with a gangster was killed while in transit, it was estimated that at least 400 bullets had been fired from AK-47 rifles.

The police in India don’t have easy access to automatic weapons. Nearly half the police force has been using weaponry declared outdated twenty years ago.21 In 2017, it emerged that 267 police stations didn’t even have telephones and 273 stations had no transportation vehicle. Over 45 per cent of the police stations minus telephones were in Uttar Pradesh.

A monk from the order of Nath Jogis became chief minister of the state in 2017. Yogi Adityanath alias Ajay Singh Bisht was once quoted as saying, ‘I find western UP unsafe. We do not face a threat in eastern UP because there we use the language that people understand and set them straight.’22 He too had three charges of rioting against him, one attempt to murder, one charge of endangering others’ lives, two cases of trespassing on burial places, one charge related to criminal intimidation.23 After he assumed office, all charges were dismissed.

Meanwhile, the chainmail linking guns, businessmen and the formal political system has got stronger with each election cycle. At the time of writing, 106 of the 521 members of Parliament have been booked for crimes such as murder, inciting communal disharmony, kidnapping and rape. Here too, Uttar Pradesh leads.

*

It wasn’t always like this. There was a time Azamgarh was a socialist stronghold. Local leaders raised slogans like: Ye azaadi jhooti hai; desh ki janta bhooki hai. Our freedom is a lie; the people are still hungry.

In the 1980s, however, the political culture changed dramatically, and the reputation for poetry and textiles was replaced by a reputation for lawless men who had little to lose. Mumbai’s mafia was partly to blame. The gangs were hiring freelance shooters, paying as little as INR 5,000–10,000 (USD 70–140) for a hit job.24 These killings served as warnings through which millions could be extorted from potential victims.25 The young men who killed for such paltry sums often had no criminal records and, after the hit, melted back into the landscape from where they had come. Some of them, however, were traced to Azamgarh and this small town acquired a reputation for danger rather than Mumbai, which was home to an underworld described as a ‘well-oiled machine’ with an annual turnover several times the municipal budget.26

Goons and gangs, however, were not as damaging as the third round of stereotyping. This time it was linked to terror – a word deployed with terrifying precision, for terrifying ends.

Azamgarh has had few moments of communal tension. However, a narrative has been drummed up that seeks to isolate and demonise Muslims ever since a mob led by Hindutva organisations demolished the Babri Masjid in 1992, followed by riots and bomb attacks. In subsequent years, the Students’ Islamic Movement of India was banned under anti-terror laws and among its office bearers were men who had origins in Azamgarh.

The narrative around Azamgarh grew wings in 2008. After a series of bomb blasts in Delhi, the police claimed that suspects were hiding in a place called Batla House. Police killed two young men, both from Azamgarh, arrested a third, and claimed that two others escaped.

Concerted efforts have since been made to paint the whole district with the brush of terror. These are really efforts to reconfigure a political constituency that has traditionally voted centre or left.

Yogi Adityanath has considerable influence in seven eastern UP districts but less so in Azamgarh and Mau. His influence is exercised through organisations like Hindu Yuva Vahani, Hindu Jagran Manch and several others. Some of their members’ interventions led, in part, to the Mau riots of 2005.

It started, as it usually does, with contested space: land, right of way, cultural assertation. A Hindu festival was coinciding with Ramzan. A citizens’ investigation later found that the 2005 riot could have been prevented, were it not for aggressive posturing by groups like the Hindu Yuva Vahini. Citizens who attempted to keep the peace were accused of cowardice.27

The legislator at the time was Mukhtar Ansari. He has been arrested on various counts over the years, but during the Mau riot he was out and trying to calm people down. However, when a video surfaced, television channels broadcast it with the sound muted. Nobody could tell that Ansari was trying to stop the riot: all they saw was a Muslim representative out with his men. Newspapers went further. The Times of India carried a front-page headline saying, ‘Feeling of insecurity grips Hindus in Mau’, giving the impression that Hindus were being targeted when in fact Muslims were the terrified minority.

One of the writers of the citizens’ report, V. N. Rai, is a retired cop and the author of an analysis of communal riots in India. He found great anti-Muslim bias within the police force and a gross under-representation of Muslims in the police and the armed constabulary.28 This bias has been reconfirmed in recent surveys, which show that many police officers believe Muslims and Dalits are more prone to committing crimes.29

Over the last two decades, dozens of young Muslim men have been picked up without much evidence and tortured for years while in custody. Rajeev Yadav and his colleagues have set up an organisation called Rihai Manch that works specifically on finding legal redress for such youths.

Instead of addressing institutional bias, the home minister of India30 as well as the chief minister of the state continue to make statements linking Azamgarh with terrorism.31 This serves the dual purpose of isolating and frightening Muslims while preventing the Hindu majority from taking pride in their regional identity, thus shattering old bonds of regional affiliation and class solidarity.

*

The phrase ‘native place’ has great currency in India. People use it as an English substitute for Hindi words like mulk and vatan, which refer to both country and home. Migrant workers sometimes disappear from city jobs for weeks, and enquiries reveal that they have gone to their mulk. It is where families and farmlands are, or where they trace their roots, as we do in eastern Uttar Pradesh.

On my first visit here, I found the soothing flatness of the horizon reach into some part of me that wants to be captured, the way trees capture earth. I remember looking at the remnants of a crumbling wall made of flat lakhori bricks, trees growing out of the walls of my great-grandmother’s kitchen, and thinking, is this my vatan?

I keep an eye open for goondaism: raised voices, fisticuffs, a revolver or rifle, glowering eyes. What I find instead is patience and forbearance, and a poverty so keen that sixteen people routinely squish into a vehicle meant for four. Passengers quibble over a single rupee worth of carriage fare. One Indian rupee can no longer buy anything, not even the sugary imarti. But ten such trips where one rupee is saved after humiliating bargains could add up to one sweet for a child waiting at home. I notice how thin everyone is.

I watch poorly made videos on YouTube about how to make jaggery: women stripping cane, mud stove, a vat, the drape and fall of cheap sarees, shawls in winter. These are not my memories. My mother would never drape a saree in that style, nor does she know her way around a wood-fired stove. Why does it all look familiar?

I go looking for artists and find a national Sangeet Natak award-winning32 theatre director and a troupe called Sutradhar that performs in a cinema hall with perforated walls that stopped screening movies long ago. The group performs and people are encouraged to pay 5 rupees, because that’s what it costs to rent a chair for the evening. On good days, I’m told, busloads of people travel hours to watch a performance.

In my head, I tell my grandfather: It’s not a cultural desert.

In my head, I see him smile at my bristling defence as if he were glad, but also sceptical: Are you moving here, then?

No. This might have been our vatan, his and mine, but it’s not our zameen. The word zameen also has dual connotations. It means land, but also a certain psychological environment. It is soil, mood, air, culture, space. It can be prepared, created, levelled, ruined. It is where you blossom and fructify. You make it as much as you need it to make yourself.

Grandpa didn’t want to spell it out, but he was probably wary of the vigilance, the tenacity that land requires. He didn’t hold onto his father’s land and he never bought any himself. His zameen was language and literature, and there he remained comfortably rooted all his life. And how different am I?

Lying on a hard floor in Mom’s morsel-sized room, in the middle of yet another power cut, I watch the ancestral sky turn a deep Prussian blue, and I wonder if I am making a mistake, looking for roots that I can’t quite put down.

Even so, I have begun to tell people that my roots are in district Mau-formerly-in-Azamgarh. Its reputation stopped bothering me once I woke up to the fractured nature of law enforcement and the limitations of a judicial process that’s heavily dependent on a biased, unrepresentative and under-equipped police force.

One of the men who win elections, in or out of jail, had famously declared that even God can’t control crime in this state.33 Sometimes I think, maybe God has a good reason for not intervening. What does it mean: law, crime, goondaism? Whose crimes are annulled, whose crimes magnified? If a man can be tempted to board a train from his village to Mumbai to kill a stranger for 5,000 rupees, one has to ask: who is being made to feel that human life is cheap?

Every day, we see reports of laws being used against those who go looking for justice, and allegations of police failing to collect or present evidence in court, or cultivating false testimony, or killing or raping people in custody. Some are crimes so brutal, the only thing that makes them worse is the knowledge that they were perpetrated by men in uniform, and that the individual was not stopped by the conscience of the collective. There is very little standing between the unarmed citizen and the abyss.

Goondagardi is not a label that can be tacked onto any specific geography. I now see goondaism and policing, law and outlaw, not as separate categories but as behaviours. In places where people are aware that right and wrong is different from legal and illegal, and where the simplest way of getting on the right side of the law is to become a lawmaker yourself, words like lawlessness have little meaning. If you emerge unscathed from such places, if you escape feudalism, caste, bigotry, corruption, hunger, and someone else’s rage, be grateful. There, but for the grace of God …

Still, you have to recognise the crucible, and if you can put anything good into it, do so. Maybe that’s what Grandpa meant by, never forget your roots?

Nowadays when people mention the goondaism in my native place, I react like a cow chewing cud. I resist expostulation and say, yeah, the imarti is famous too.

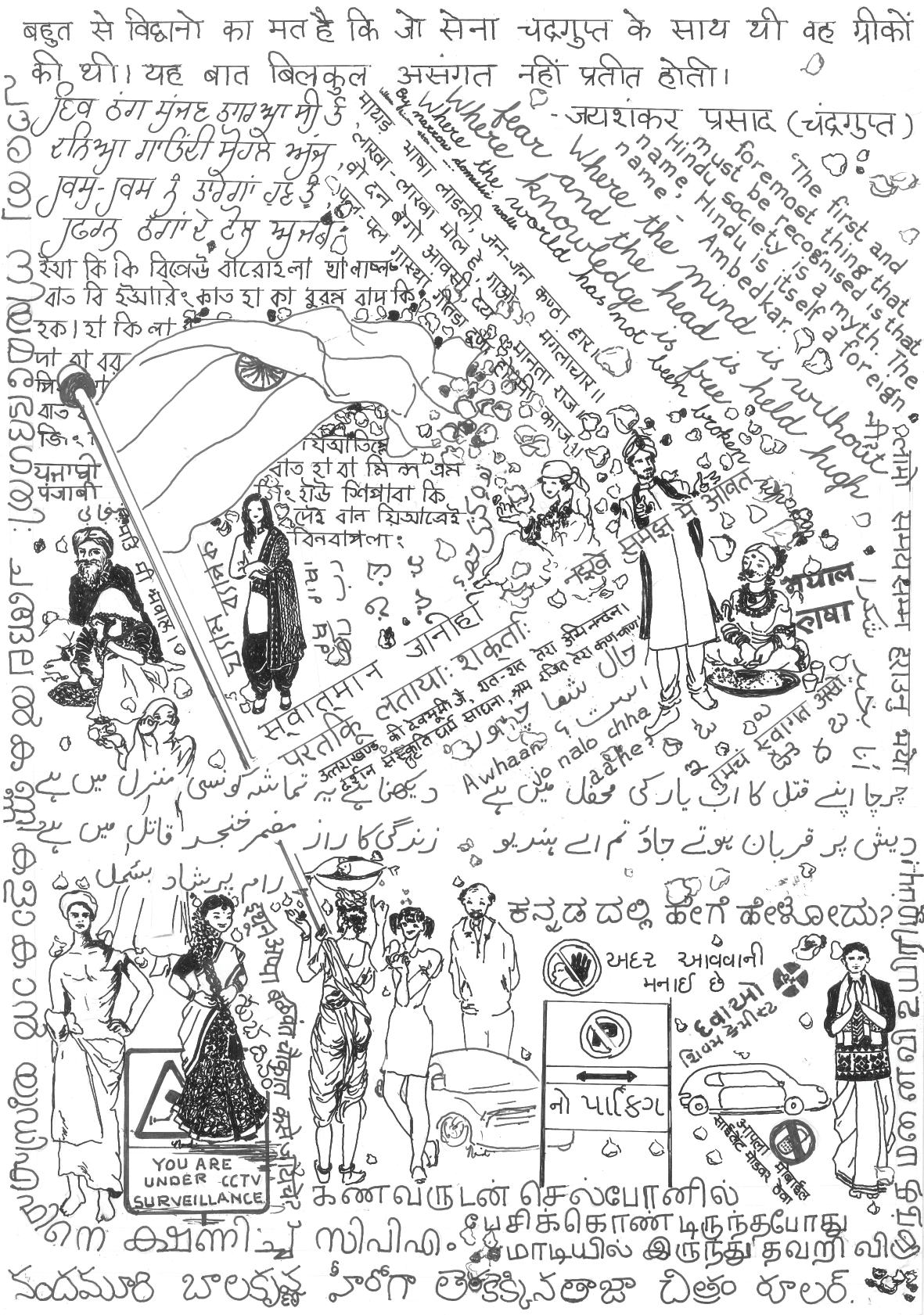

India is home to 122 distinct languages of which Hindi can claim the greatest number of speakers.