Introduction

Rapid population ageing is linked to the progressive improvements of living conditions, health care and public health initiatives (World Health Organization (WHO), 2015). Longer lives are a valuable resource, both for the individuals and for society, but the increasing proportion of the older population, defined by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare as those ⩾65 years (Socialstyrelsen, 2018), also poses a global demographic challenge (United Nations, 2015a; WHO, 2017). The extent of the challenge that arises from increased longevity will be heavily dependent on one key factor: the health and wellbeing of the older population. Ensuring the best possible health and wellbeing in older age is therefore crucial if we are to achieve sustainable development in which the needs and rights of older people are adequately addressed (United Nations, 2015b). As a response, the WHO has launched a global strategy and action plan that is required to ensure that everyone can experience both a long and healthy life, or so-called ‘healthy ageing’ (WHO, 2017).

There is no consensual definition of the concept ‘healthy ageing’, although definitions are plentiful in the academic and policy literature, and many definitions share common features (McKee and Schüz, Reference McKee and Schüz2015). The Swedish National Institute of Public Health (Folkhälsoinstitutet (FHI), 2009: 9) defines ‘healthy ageing’ as ‘the process of optimising opportunities for physical, social and mental health to enable older people to take part in society without discrimination and to enjoy an independent and good quality of life’. The Swedish National Institute of Public Health concludes in its report, Healthy Ageing. A Challenge for Europe, that the ‘cornerstones’ of ‘healthy ageing’ are physical activity and healthy eating, social interaction, a sense of meaningfulness, and a sense of personal control and empowerment (FHI, 2009). Building on the two ideas of capacity and ability, the WHO (2015: 228) defines ‘healthy ageing’ as ‘the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age’. ‘Healthy ageing’ thus reflects the ongoing interaction between individuals and the environments they inhabit. In the ‘healthy ageing’ agenda, older people are expected to take responsibility for their health by making certain leisure and lifestyle choices, and a moral viewpoint has emerged about good/successful/productive and bad/unsuccessful/unproductive ways to age. The overemphasis on individual action and lifestyle choice tends to ignore the influence of social forces, social inequalities and cultural constraints on health outcomes (Katz and Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2015). Thus, a critique of the ‘healthy ageing’ agenda is that the overriding assumption is that lifestyle choices are volitional, and the agenda somewhat neglects the understanding of age inequalities and social determinants of health in later life and the diversity of the ageing experience itself (Katz, Reference Katz2013).

The WHO's (2017) recommendations for policies to promote healthy ageing have influenced the strategies of many Western countries. Today, social policy in the United States of America, Europe, Australia and Asia is framed in terms of promoting health and independence among older people to reduce the burden on health and welfare systems, while supporting self-care and other services that enable older people to remain in their own homes (Coyte et al., Reference Coyte, Goodwin and Laporte2008; Häkkinen et al., Reference Häkkinen, Martikainen, Noro, Nihtilä and Peltola2008; Stenner et al., Reference Stenner, McFarquhar and Bowling2011). The discourse on healthy ageing positions older people as being responsible for engaging in healthy living and social activity (Stephens et al., Reference Stephens, Breheny and Mansvelt2015). In the Swedish context, healthy ageing is closely linked to ‘ageing in place’ (FHI, 2009), which refers to the ability to live independently in one's own home for as long as one feels confident and comfortable (Yen and Anderson, Reference Yen and Anderson2012). The notion of ageing in place assumes that the benefits outweigh the disadvantages, provided that the health and social care needs of the older person can be supported (Sixsmith et al., Reference Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Malmgren Fänge, Naumann, Kucsera and Tomsone2014). This is dependent upon sufficient environmental and social supports being provided at home (Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Josephsson and Lilja2009) as well as the older person's physical ability to retain a high quality of life, level of activity and sense of independence (Sixsmith et al., Reference Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Malmgren Fänge, Naumann, Kucsera and Tomsone2014). Sweden has the highest life expectancy in the European Union, and the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs foresees a staff shortage of 65,000 work years of professional caregivers in the elderly care sector by 2030 (Socialdepartementet, 2010); the critical question is whether the health and welfare system can support ageing in place (Yen and Anderson, Reference Yen and Anderson2012). Preventive and supportive work is thus focused on maintaining independence, that is, allowing older people to live longer in their own homes with the possibility to act independently and to participate actively in society, and on delaying age-related health and social care needs (Bloom et al., Reference Bloom, Chatterji, Kowal, Lloyd-Sherlock, McKee, Rechel, Rosenberg and Smith2015; WHO, 2017).

There is a limited body of knowledge on what it entails for older people to maintain health and independence, have the possibility to live under safe conditions, and live an active and meaningful life (Hornby-Turner et al., Reference Hornby-Turner, Peel and Hubbard2017). This knowledge is essential for the preparation of appropriate policies and effective health and social interventions to respond to the challenges brought about by global ageing. Empowering older people to recognise and build on their health and independence may help protect and promote health status in older age.

Furthermore, opportunities for self-realisation and self-development can be compromised if experts and authorities plan and implement health promotion objectives and programmes for older people in a ‘top-down’ manner. This ‘paternalistic’ approach can be reduced by enabling people who have knowledge, experience and opinions in the field to have their say (FHI, 2009; National Institute for Health Research, 2012; Brett et al., Reference Brett, Staniszewska, Mockford, Herron-Marx, Hughes, Tysall and Suleman2014), thus we included older persons, next of kin of older persons, health and care professionals, care managers and local politicians.

The aim of the current study was to explore the prerequisites for a healthy and independent life among older people in Sweden.

Methods

Design

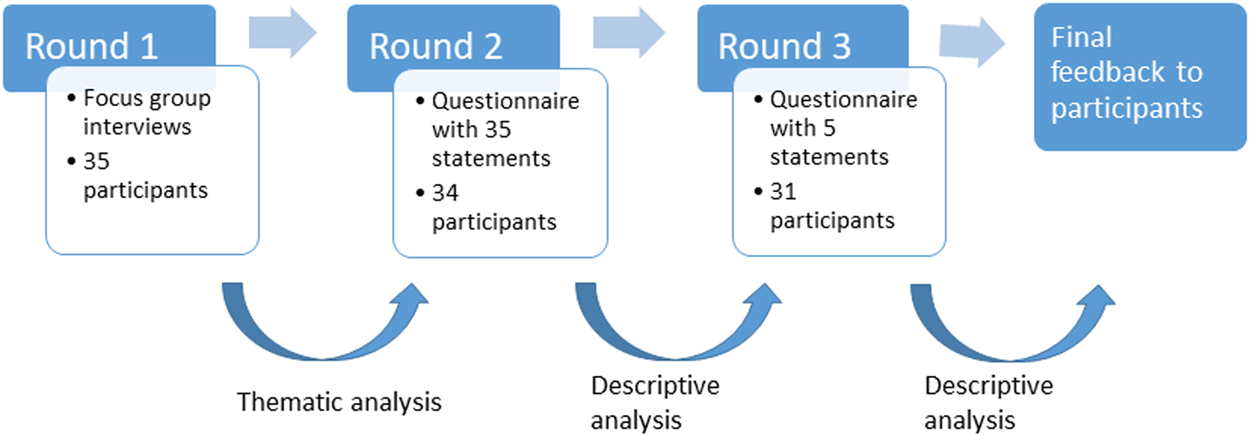

A Delphi study was conducted in three rounds (Keeney et al., Reference Keeney, Hasson and McKenna2011). The first round consisted of focus group interviews, while the second and third rounds consisted of questionnaires, formulated as statements and distributed via email. Delphi is used to avoid problems arising from powerful personalities, group pressure and the effects of status. Used as an alternative to conventional surveys, the Delphi technique allows greater interaction with respondents via feedback and justifications, and permits respondents to reconsider and modify their responses (Goodman, Reference Goodman1987).

Setting, recruitment and participants

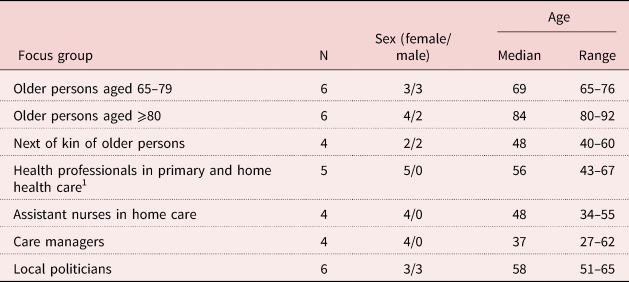

The study was conducted in one county in the mid-east of Sweden. Recruitment was carried out through verbal and written requests to retirement associations, family associations, managers in primary care and the municipality, the municipal council as well as through private contacts. Purposeful sampling was used to recruit participants to the study. The inclusion criteria were age, profession and being next of kin of older persons (65 years and older). The exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment and an inability to understand and speak Swedish. An even distribution regarding sex and variations in ethnicity were strived for, and for the professional groups, a variation in professions was sought. Seven groups were formed, with four to six participants in each group, for a total of 35 participants. The participants were distributed into the following seven groups: older persons aged 65–79, older persons aged ⩾80, next of kin of older persons, health professionals in primary and home health care, assistant nurses in home care, care managers and local politicians. Participants to the focus groups in the first round were contacted by the research assistant and the time and place for the focus group interviews were agreed. Written information about the study and a form on informed consent were sent to the participants. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants in the seven focus groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants in each of the focus groups

Note: 1. Registered nurses, occupational therapist and physiotherapist.

Data collection and analyses

Delphi round 1: focus group interviews

An interview guide was developed in accordance with the research of Krueger and Casey (Reference Krueger and Casey2015), moving from general to specific questions. The introductory questions asked the participants to brainstorm about how it is to grow old in Sweden from both an individual and a societal perspective. These questions were followed by transition questions regarding the participants’ thoughts about the meaning of a healthy life and an independent life for older persons. The key questions focused on the areas that emerged in a previously conducted scoping review (unpublished material) regarding a healthy and independent life for older persons: living a healthy life, living an independent life, having an active life, living a meaningful life, using health and welfare technology for support in daily life, having satisfactory communication and, lastly, experiencing safety. A pilot focus group interview was conducted with five older persons and health professionals to determine the feasibility and usefulness of the interview guide (Creswell, Reference Creswell2009). The questions and order of questions in the interview guide were then clarified and refined. Thereafter, one interview was performed with each of the aforementioned groups during September and October 2017. Six of the interviews took place at the local university and one interview was held at the participant's workplace. All focus group interviews were conducted by a moderator accompanied by an assistant moderator, who were the same persons in all interviews. Each focus group interview lasted for 90 minutes and was digitally audio recorded.

The recordings were transcribed verbatim by the members of the research team. Thematic analysis was performed, using an inductive semantic approach (Braun and Clark, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The analysis began with the reading and re-reading of the transcribed material. Data extracts were identified, which generated a multitude of codes. Codes were then collated in a search for potential themes. Lastly, the themes were reviewed on two levels: level 1 involved reviewing themes in relation to the coded data, and level 2 involved reviewing themes in relation to the entire data-set. From the generation of codes and themes, preliminary statements corresponding to the aim of the study were formed. Table 2 shows some examples of the coding process resulting in preliminary themes and preliminary statements.

Table 2. Examples of the coding process in round 1 resulting in preliminary themes and preliminary statements corresponding to the aim of the study

Delphi rounds 2 and 3: evaluation of statements

In the second round, a list of statements was created based on the results of the focus group interviews in the first round. The list was sent to all participants from the first round with an information letter. The participants were asked to evaluate the degree to which they agreed with each statement as being a prerequisite for a healthy and independent life, using a four-step Likert scale, ranging from 1 (totally agree) to 4 (totally disagree). The level of consensus was set at 80 per cent, meaning that at least 80 per cent of the participants did ‘agree’ (1 or 2 on the Likert scale) or ‘disagree’ (3 or 4 on the Likert scale) with each statement (Hasson and McKenna, Reference Hasson and McKenna2006). Additionally, the participants were asked to identify which three statements they considered to be of most importance for a healthy and independent life for persons 65 and older. In the third round, statements that did not meet the criteria for consensus in round 2 were sent out again with information about the statements’ level of consensus in the previous round. Participants were again asked to evaluate their level of agreement with each statement. Again, the participants were asked to identify which three statements they considered to be of most importance, but now choosing from seven statements. These statements were evaluated in round 2 as one of the three most important prerequisites in more than 5 per cent of the evaluations. See Figure 1 for the Delphi process of the three rounds.

Figure 1. The Delphi process.

The external drop-out was one person in round 2 and three persons in round 3, resulting in 34 participants in round 2 and 31 in round 3. Two reminders were given by email, mail and telephone to non-responders. The missing values in round 2 totalled 1.4 per cent and the imputation of the item mean score was used (Huisman, Reference Huisman2000).

Ethical guidelines

The participants were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they could end their participation whenever they wanted to. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. The study was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (Dno. 2016/573) and conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2015).

Results

Delphi round 1: focus group interviews

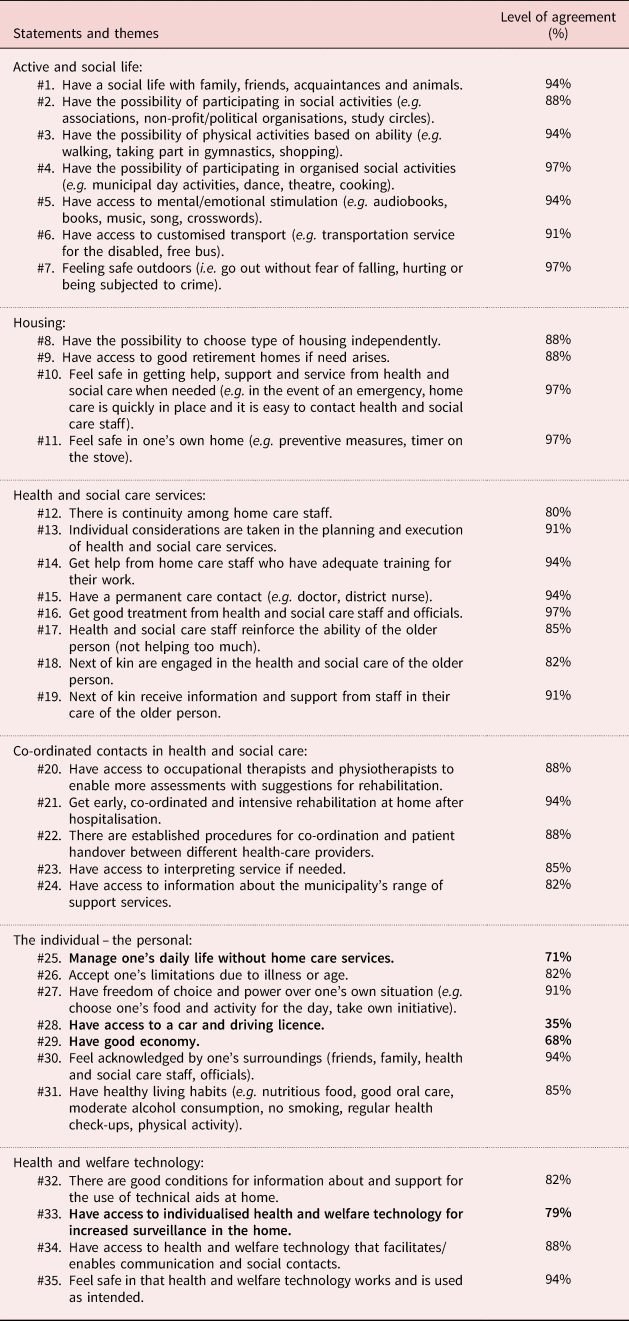

The thematic analysis of the focus groups interviews in round 1 resulted in 12 preliminary themes and 50 preliminary statements, which were derived from the collation of codes. The 12 themes were housing, social network, health and welfare technology, health prevention/healthy living, home care, the individual – the personal, the system, safety and security, activities, resources, dignity and independence. The 12 themes and 50 statements were then reviewed according to their similarities and differences, which resulted in a reduction into six themes, including 35 statements. The six themes were active and social life (statements 1–7), housing (statements 8–11), health and social care services (statements 12–19), co-ordinated contacts in health and social care (statements 20–24), the individual – the personal (statements 25–31) and health and welfare technology (statements 32–35), which were sent out in round 2.

Rounds 2 and 3: consensus about statements

Thirty out of the 35 statements achieved consensus at the 80 per cent level in round 2. Accordingly, the remaining five statements (#12, #25, #28, #29 and #33) were sent out in round 3 with information on the results from round 2. Out of these five statements, statement #12 achieved consensus in round 3. The 31 statements that achieved consensus were agreed upon as being prerequisites for a healthy and independent life among older people (Table 3).

Table 3. Level of agreement for each statement, divided by the six themes, after round 3

Note: Statements that did not achieve consensus are bold.

After the completion of the three rounds there was an agreement of at least 80 per cent on almost all (31/35) statements derived from the focus group interviews with different groups of people, that is, older persons themselves, next of kin, health and care professionals, and decision makers on different levels. Five statements reached the level of agreement of 97 per cent, meaning 34 (of 35) participants agreed that the following statements were prerequisites for a healthy and independent life: #4 – Have the possibility to participate in organised social activities (e.g. municipal day activities, dance, theatre, cooking); #7 – Feeling safe outdoors (i.e. go out without fear of falling, hurting or being subjected to crime); #10 – Feel safe in getting help, support and service from health and social care when needed (e.g. in the event of an emergency, home care is quickly in place and it is easy to contact health and social care staff); #11 – Feel safe in one's own home (e.g. preventive measures, timer on the stove); and #16 – Get good treatment from health and social care staff and officials.

Four statements did not achieve consensus: #25 – Manage one's daily life without home care services (71%); #28 – Have access to a car and driving licence (35%); #29 – Have good economy (68%); and #33 – Have access to individualised health and welfare technology for increased surveillance in the home (79%). For two of these statements there were some noteworthy group disagreements. Regarding #25 – Manage one's daily life without home care services, ten of the 12 older persons considered it a prerequisite for a healthy and independent life, while three of nine assistant nurses in home care and care managers did. Further, regarding #33 – Have access to individualised health and welfare technology for increased surveillance in the home, all 12 older persons and all five politicians considered it a prerequisite for a healthy and independent life, while 12 of the 17 participants in the other groups did (Table 3).

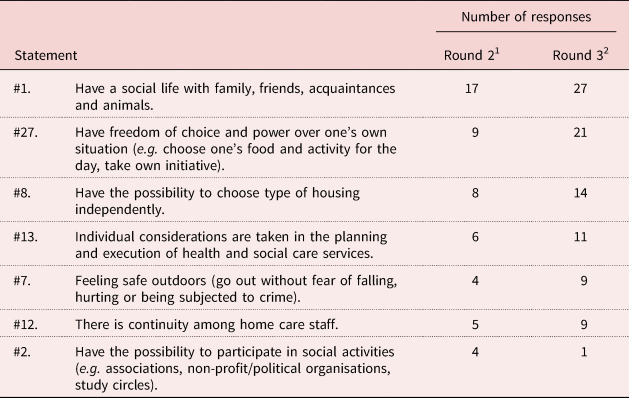

The participants were also asked to identify the three prerequisites of most importance for a healthy and independent life for persons 65 and older. The following three statements were stated as being of most importance by most participants in both rounds 2 and 3: #1 – Have a social life with family, friends, acquaintances and animals; #27 – Have freedom of choice and power over one's own situation (e.g. choose one's food and activity for the day, take own initiative); and #8 – Have the possibility to choose type of housing independently ( Table 4).

Table 4. Prerequisites of most importance for a healthy and independent life for persons 65 and older, rounds 2 and 3

Notes: 1. Thirty-four participants identified the three prerequisites of most importance among 35 statements. 2. Thirty-one participants identified the three prerequisites of most importance among seven statements.

Discussion

The results of the current study revealed several areas of importance for a healthy and independent life. The discussion will mainly focus on different aspects of three intertwined areas of importance: social life, safety and freedom of choice. Firstly, and not unexpectedly, to have a social life was stated as one of three prerequisites of most importance by most participants, and to participate in organised social activities reached a level of agreement of 97 per cent. People are by nature social beings (Cohen, Reference Cohen2004). Yet, the quantity and quality of social relations have sharply decreased in the modern way of life in industrialised countries, and an increasing proportion of people of all ages live alone. There is also reason to believe that people will be increasingly socially isolated with a negative impact on their health (Cohen, Reference Cohen2004; McPherson and Smith-Lovin, Reference McPherson and Smith-Lovin2006). A meta-analysis of 148 prospective studies (Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010) showed that people with stronger social relationships had a 50 per cent increased likelihood of survival compared to those with weaker social relationships. Holt-Lunstad et al. (Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris and Stephenson2015) also showed that loneliness and social isolation can lead to functional decline and hasten death. The social isolation and loneliness that can occur as one ages, often alone in one's home, can lead to a loss of social identity, self-worth and sense of meaningfulness in life.

Secondly, to feel safe outdoors and in one's own home and receive good treatment in health and social care had a high level of agreement (#7, #10, #11, #16; 97%), and there was also a high level of agreement in feeling safe regarding that health and welfare technology works and that it is used as intended (#35; 94%) as a prerequisite for a healthy and independent life. A growing body of evidence suggests that health and welfare technology can support a healthy and independent life, social relations and meet individual needs of older people (Eisma et al., Reference Eisma, Dickinson, Goodman, Syme, Tiwari and Newell2004; Magnusson et al., Reference Magnusson, Hanson and Nolan2005; Koch, Reference Koch2006; European Union, 2013, 2014; Lee and Coughlin, Reference Lee and Coughlin2014; Peek et al., Reference Peek, Wouters, van Hoof, Luijkx, Boeije and Vrijhoef2014, Reference Peek, Luijkx, Rijnaard, Nieboer, van der Voort, Aarts, van Hoof, Vrijhoef and Wouters2016). Göransson et al. (Reference Göransson, Wengström, Ziegert, Langius-Eklöf, Eriksson, Kihlgren and Blomberg2017) concluded that it was essential to include social relationships and social activities in interactive information and communication technology (ICT) platforms aimed at older people. These findings, together with the findings from the current study, in which the importance of a social life also was reflected in the prerequisite of having access to health and welfare technology that facilitates/enables communication and social contacts (#34; 88%), indicates that the social aspects are relevant to older people's motivation to use ICT and should be integrated in interactive ICT platforms.

Several studies have shown that social internet-based activities improve older people's social life, decrease loneliness and promote a sense of safety (Eisma et al., Reference Eisma, Dickinson, Goodman, Syme, Tiwari and Newell2004; Magnusson et al., Reference Magnusson, Hanson and Nolan2005; Koch, Reference Koch2006; Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Nilsson and Larsson Lund2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Wei, Yao, Yuan, Shan and Yuan2014; Åkerlind et al., Reference Åkerlind, Martin and Gustafsson2018), yet there are still large groups who are excluded from social internet-based activities (Olsson et al., 2019). A lack of technical support may be one explanation (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Nilsson and Larsson Lund2013) and social websites that are not adapted for older people may be another (Nahm et al., Reference Nahm, Preece, Resnick and Mills2004; Chauffin and Maddux, Reference Chauffin and Maddux2007). Issues of safety, trust and reassurance in the use of health and welfare technology, issues that were clearly important to the participants in the current study, are important to address. Given the ageing population and need to improve care processes and care for the older population, health and welfare technology offers great promise, yet the potential is tempered by lagging adoption by older people and human factors challenges (Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Grundy, Robine, Cylus, Mackenbach, Knai and McKee2013; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, David, Crotty, Dierks and Safran2014). Johansson-Pajala et al. (Reference Johansson-Pajala, Thommes, Hoppe, Tuisku, Hennala, Melkas and Gustafsson2019) concluded that a successful implementation of health and welfare technology heavily depends on receiving relevant information, meeting older people's authentic needs and considering the hesitance of professional caregivers. In the results of the current study, only 12 of the 17 health professionals in primary and home health care, assistant nurses in home care and care managers considered having access to individualised health and welfare technology for increased surveillance in the home to be a prerequisite for a healthy and independent life (#33), while all 12 older persons and all five politicians did. This finding is not surprising as a resistance among professional caregivers to implementation of health and welfare technology has been recognised previously. The main source of resistance was a fear of not coping with the new technology, a resistance to participate in collaborative processes and resistance arising from ethical concerns (Nilsen et al., Reference Nilsen, Dugstad, Eide, Gullslett and Eide2016).

Thirdly, to have the freedom of choice and power over one's own situation, and to choose one's type of housing independently were stated as two of three prerequisites of most importance by most participants. The prerequisite of retaining one's personal control and empowerment is in line with the work of Sixsmith et al. (Reference Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Malmgren Fänge, Naumann, Kucsera and Tomsone2014), who found that maintaining a level of psychological, social and environmental control was a key factor in maintaining an active, healthy and independent lifestyle among 190 older people living in five European countries. Moreover, the relationship between home, past life and identity created a meaningful space in which the participants emphasised the symbolic qualities of the home, often leading them to prefer a sub-optimal living environment that was familiar and reflective of self rather than practically supportive (Sixsmith et al., Reference Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Malmgren Fänge, Naumann, Kucsera and Tomsone2014). A recent review by Hornby-Turner et al. (Reference Hornby-Turner, Peel and Hubbard2017) found that older people's ability to make their own choices and their will to maintain their independence are important protective factors or ‘health assets’. ‘Health assets’ are defined as an individual's internal or external strengths or accessible resources which enhance their ability to optimise health (Rotegård et al., Reference Rotegård, Moore, Fagermoen and Ruland2010). Empowering people to recognise and build on their potential health assets, such as the power of choice and maintenance of independence, may help protect and promote health status. Identifying health assets that positively influence or protect health in older age is thought to support the design of effective policies and programmes for the promotion of health in older age (Hornby-Turner et al., Reference Hornby-Turner, Peel and Hubbard2017).

There is a complexity in the interconnection between the three areas of importance for a healthy and independent life found in the current study. In the Swedish context, ageing in place assumes that the benefits of living in one's home outweigh the disadvantages so long as the social, safety and health needs of the older people can be supported. If sufficient support cannot be provided, the notion of ageing in place also fails to address the older people's freedom of choice and independent decision making in those cases when the older people do not wish to move from their home. On the other hand, advanced ageing in one's home, despite being sufficiently supported, can also result in decreased levels of safety and freedom of choice, and growing levels of loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Shmotkin and Goldberg2009; Thomas and Blanchard, Reference Thomas and Blanchard2009; Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler and Bond2012). Furthermore, older people's capacity of independent decision and securing a healthy and safe living with social activity will depend upon the diversity of their ageing experience, health statuses, and social and cultural inequality, as previously discussed by Katz (Reference Katz2013), Katz and Calasanti (Reference Katz and Calasanti2015) and Stephens et al. (Reference Stephens, Breheny and Mansvelt2015).

In view of previous research, the three areas of social life, safety and freedom of choice in the current study highlight that interventions in older people's environment need to balance between being respectful of older people's entitlement to control and the values older people attach to home, while also supporting their safety and social life. Also, as older people constitute a very heterogeneous group (Lindenberger et al., Reference Lindenberger, Lövdén, Schellenbach, Li and Krüger2008), a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to succeed. The heterogeneity is further problematised by Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2013) who identify that ageing has changed from a process once described as that of ‘structured dependency’ to an arena, where agency and effort are always expected by working tirelessly on lifestyle, leisure and consumption. There is a paradox to the expectations of older people to be active, successful and productive members of society. On the flipside to these expectations of ‘healthy ageing’ practices are older people themselves, engaging in meaningful, non-traditional and new-normative leisure activities, despite societal pressures to ‘just act your age’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2013). Hence, a strength of the current study is the inclusion of a heterogenous sample to obtain an overall heterogeneity of views and to involve policy makers on a regional and municipal level as they are responsible in the creation of physical, social and age-friendly environments.

The involvement of policy makers in research is also essential for an increased awareness of accessible and sustainable measures to take on a regional, municipal and national level. If there is consensus among older people, next of kin, care providers and policy makers, we can also be more optimistic about the creation of an age-friendly context that reflects this consensus. To date, there is a growing consensus regarding the components of age-friendly efforts, and a key component is the investment in older people through community social groups, organisations of older people and self-help groups (WHO, 2007, 2017). Another strategic objective is adaptable, flexible housing that accommodates the changing needs of people as they age (McLaughlin and Mills, Reference McLaughlin and Mills2008), which needs to take older people's cognitive functioning into consideration as it is strongly associated with a person's ability to maintain health and independence through activities of daily living (Mlinac and Feng, Reference Mlinac and Feng2016; Burzynska, Reference Burzynska2017). Moreover, the service intervention ‘reablement’ is being adopted across high-income countries to promote independence and support older people in their endeavours to retain, regain or gain skills (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016). Reablement is an individualised care provision supporting independent living. It should be goal-orientated, holistic and person-centred: working to achieve participation in daily activities that matter to the older person and supporting them in their pursuit of their chosen lifestyles within their familiar and local context. Policies in many countries are increasingly promoting short and intensive reablement services to replace conventional care provisions, which are often long term or even permanent (Tuntland et al., Reference Tuntland, Aaslund, Espehaug, Førland and Kjeken2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016). Scharlach et al. (Reference Scharlach, Davitt, Lehning, Greenfield and Graham2014) found that the Village model, a social initiative that emphasises member involvement and service access, is helping communities to become more age-friendly. Hopefully, a consensus built on heterogenous voices will ultimately form a socio-ecological context for ageing, even though older people who have the means, ability and desire to take individual action will nevertheless test the boundaries of what it means to be ‘old’ and create new definitions of ageing at the individual, interpersonal and community levels (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2013).

Strengths and limitations

The aim of the Delphi technique research is to determine, predict and explore group attitudes, needs and priorities (Hasson and Keeney, Reference Hasson and Keeney2011). No firm guidance exists regarding the size, composition and selection of participants in a Delphi study, but it has been suggested that a heterogeneous sample should be used to ensure that the entire spectrum of opinion is determined. This can be achieved by including different panels of experts (Keeney et al., Reference Keeney, Hasson and McKenna2011). The current study included older people from different age groups, next of kin, health and care professionals, care managers working with older people and local politicians. A limitation of the sample was our omission in collecting information about the participants’ social class, level of education and work experience. There were more women than men, which reflects the demographic reality (Davoudi et al., Reference Davoudi, Wishardt and Strange2010) as there is an over-representation of women working in health and social care, women live longer and the next of kin who provide the most comprehensive care for a next of kin are women (Sand, Reference Sand2014). To minimise the risk that differences in perspective, e.g. between the older people and the local politicians, may have inhibited the discussions, the groups were interviewed separately to make the participants feel comfortable in expressing their thoughts and perceptions (McLafferty, Reference McLafferty2004).

Only one participant dropped out in round 2 and three participants in round 3. A characteristic of Delphi studies is that the response rate of participants declines as the number of rounds progresses (Keeney et al., Reference Keeney, Hasson and McKenna2011). However, in the current study a high level of response rate was obtained. One reason may be that follow-up reminders were made through three channels (email, mail and telephone) to non-responders.

A wider inclusion of participants in rounds 2 and 3 might have resulted in a different rating of the statements. In round 3, only the five statements that had not achieved consensus in the previous round were sent out again to avoid additional drop-outs in round 3. On the other hand, this strategy gave the participants in round 3 no opportunity to re-evaluate their opinions of the other 30 statements.

The intention was to involve all stakeholders or users in the care of older people, including older people themselves. Studies have shown that involving users in the interpretation of collected data can be a challenge due to differences in knowledge and understanding between researchers and users (Kylberg et al., Reference Kylberg, Haak and Iwarsson2018). Although, in general, this approach in the research process improves the research study quality (National Institute for Health Research, 2012; Brett et al., Reference Brett, Staniszewska, Mockford, Herron-Marx, Hughes, Tysall and Suleman2014), as we believe was the case in the current study. The group disagreement for statements #25 and #33 became apparent. Whilst all of us are actual, former or potential users of health and social care services, there is an important distinction to be made between the perspectives of the users and the perspectives of people who have a professional role in health and social care services (National Institute for Health Research, 2012).

The results of the current study are based on subjective experiences; hence the findings must be taken as the best achievable consensus, rather than as evidence of absolute agreement. Thus, the findings may be useful in developing a framework for further research, such as exploring and testing how social relationships can be enhanced and loneliness reduced by, for example, the use of health and welfare technology. The use of the Delphi process provides a fair representation of perspectives on the prerequisites for a healthy and independent life for people aged 65 and older.

Conclusion

There was an overall high group agreement on the prerequisites needed for a healthy and independent life among older people. The main areas of importance were to have a social life, several dimensions of feeling safe and to retain one's personal control. The findings can be useful in developing a framework for further research and for targeted actions, such as age-friendly environments with the inclusion of health and welfare technology, in the care of older people.

Data

The data material generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to the participants who shared their experiences and perceptions so generously with us. We also thank members of the Prolonged Independent Living (PrILiv) research group for their research contribution in preparing, collecting and analysing data in the current study: Sofia Christensson, Christine Gustafsson, Kerstin Jorsäter-Blomgren, Lene Martin and Charlotta Åkerlind.

Financial support

This work was supported by The Social Contract (co-operation between Mälardalen University and the surrounding municipalities and regions).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (Dno. 2016/573) and conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.