Introduction

Gambling disorder, also known as gambling addiction or compulsive gambling (Fulton, Reference Fulton2015; Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021), involves repeated problematic gambling behaviour and is characterised by a preoccupation with gambling, repeated unsuccessful efforts to control it, and results in significant negative consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition) recognises gambling as a behavioural addiction disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). National gambling surveys have found that most people have gambled at some point (Calado & Griffiths, Reference Calado and Griffiths2016). For a small proportion gambling can become problematic or develop into an addiction (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Hayer, Griffiths, Meyer, Hayer and Griffiths2009). Global estimates of problem gambling prevalence vary across countries, with past year prevalence among adults estimated at between 0.1% and 5.8% (Calado & Griffiths, Reference Calado and Griffiths2016), with two to three times as many people experiencing subclinical problem and at-risk gambling (Abbott, Reference Abbott2017). Gambling related harms are diverse (Langham et al. Reference Langham, Thorne, Browne, Donaldson, Rose and Rockloff2016; Browne et al. Reference Browne, Langham, Rawat, Greer, Li, Rose, Rockloff, Donaldson, Thorne and Goodwin2016) and can impact on the physical, psychological and social well-being of a person. Harms include negative effects on finances and mental health, relationship problems including intimate partner violence, reduced productivity, absenteeism from work, loss of employment, emotional impacts including feelings of shame and stigma, physical harms including self-harm and increased risk of suicide death (Columb & O’Gara, Reference Columb and O’Gara2018; Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, Smith and Thomas2009; Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, Suomi, Jackson, Lavis, Patford, Cockman, Thomas, Bellringer, Koziol-Mclain, Battersby, Harvey and Abbott2016; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Landon, Sharman, Hakes, Suomi and Cowlishaw2018; Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2009; Binde, Reference Binde2016; Hing et al. Reference Hing, Russell, Gainsbury and Nuske2016; Karlsson & Håkansson, Reference Karlsson and Håkansson2018). The negative consequences from gambling can also impact people around those who gamble, and the wider society (Wardle et al. Reference Wardle, Reith, Best, McDaid and Platt2018). ‘Concerned significant others’ can also experience emotional distress and negative impacts on their relationship, social life, finances, employment and physical health (Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, Rodda, Lubman and Jackson2014). On average, one person’s problem gambling affects six people (Goodwin et al. Reference Goodwin, Browne, Rockloff and Rose2017).

It has been estimated that only 7–12% of problem gamblers seek treatment (Slutske, Reference Slutske2006). Of those who do seek treatment, approximately half (45–51%) will leave prematurely (Ronzitti et al. Reference Ronzitti, Soldini, Smith, Clerici and Bowden-Jones2017; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Murphy, Turner and Sharman2020). The barriers to treatment include a lack of knowledge about services, cost, cultural and language issues (Gainsbury et al. Reference Gainsbury, Hing and Suhonen2014), as well as treatment availability and threat of stigmatisation (Dąbrowska et al. Reference Dąbrowska, Moskalewicz and Wieczorek2017). The secrecy surrounding problem gambling provides a challenge to service provision (Fulton, Reference Fulton2019). As problem gambling is often addressed at crisis point, people may not have the financial means to access services if they are not free or affordable (Fulton, Reference Fulton2019).

Existing research confirms high levels of comorbidity or co-occurring conditions among problem gamblers (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Gambling disorder has been associated with co-existing psychiatric conditions including alcohol and other substance use disorders (Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, Cowlishaw, Jackson, Merkouris, Francis and Christensen2015; Lorains et al. Reference Lorains, Cowlishaw and Thomas2011; Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Welte, Tidwell and Hoffman2015). Higher prevalence rates of problem gambling have also been found among people in treatment for substance use disorders than among the general population (Cowlishaw et al. Reference Cowlishaw, Merkouris, Chapman and Radermacher2014). The burden of harm associated with gambling has been shown to be higher than that of drug dependence and some chronic physical illnesses and similar to that of major depressive disorder and alcohol misuse and dependence (Browne et al. Reference Browne, Langham, Rawat, Greer, Li, Rose, Rockloff, Donaldson, Thorne and Goodwin2016; Browne et al. Reference Browne, Bellringer, Greer, Kolandai-Matchett, Langham, Rockloff, Du Preez and Abbott2017).

There is limited data on the prevalence of problem gambling in Ireland and no regular national survey (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). The most recently available figures indicate that almost half (49.0%) of Irish adults have participated in some form of gambling and the prevalence rate for problem gambling is estimated as 0.3%; with prevalence higher among males (0.6%) than females (<0.0%) (Mongan et al. Reference Mongan, Millar, Doyle, Chakraboty and Galvin2022). This is lower than the most recent prevalence rate for problem gambling (2.3%) reported in Northern Ireland (Dunne et al. Reference Dunne, Flynn and Sholdis2017).

Within the public health system in Ireland there is no specific public health approach for gambling disorder (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Inpatient gambling treatment is provided free of charge in the Irish public health service (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021) and most people treated for problem gambling in Ireland are treated as outpatients, primarily through addiction counselling (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Outside the public health system there are some voluntary, and privately owned or commercial service providers that offer treatment for gambling disorder using helpline support or at outpatient or inpatient settings (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Barriers to gambling treatment access in Ireland include a lack of dedicated referral pathways for treatment within mental health or addiction services and variations in the level of available service provision across healthcare regions (Columb et al. Reference Columb, Griffiths and O’Gara2018).

Gaps in knowledge and research about gambling disorder and harm in Ireland have been identified (Fulton, Reference Fulton2019; O’Gara, Reference O’Gara2018; College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, 2020). This lack of information on gambling disorder and gambling-related harm has made it more difficult to understand and address gambling-related information and service needs (Fulton, Reference Fulton2019). The aim of this study is to better understand treatment uptake and provide an understanding about those who do seek treatment for gambling in Ireland, which will inform service policy and planning. This is the first analysis of national health data to describe treatment episodes for problem gambling in Ireland.

Methods

This study is an analysis using a subset of anonymous routinely collected epidemiological data from the Irish National Drug Treatment Reporting System (NDTRS), a national database of addiction treatment in Ireland (Carew & Comiskey, Reference Carew and Comiskey2018; Kelleher et al. Reference Kelleher, Carew and Lyons2021). NDTRS data collection complies with the European Treatment Demand Indicator (TDI) protocol available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/manuals/tdi-protocol-3.0_en and is a comprehensive measure of treatment demand (Bruton et al. Reference Bruton, Gibney, Hynes, Collins and Moran2021). The TDI methodology ensures that information on people entering drug treatment is collected in a harmonised, reliable and comparable way across all European countries. Information is collected on all admissions to treatment during each calendar year. Standardised treatment data is collected at treatment service level and collated nationally. Outpatient services, inpatient services, general practices, and prisons submit data to the NDTRS. NDTRS data comprise of client demographic and socioeconomic information, referral and assessment details, up to five current problem drugs or other (behavioural) addictions, history of addiction treatment, injecting risk behaviours, treatments provided, and treatment outcome information at treatment episode end. NDTRS data coverage (numbers of admissions and treatment services reporting data) is high (Health Research Board, 2017), particularly in inpatient, outpatient and low threshold settings (Bruton et al. Reference Bruton, Gibney, Hynes, Collins and Moran2021). The NDTRS has a comprehensive process for checking and validating data before use, including a suite of automated validation checks which are applied to every episode. Reporting of gambling treatment to the NDTRS by service providers is currently voluntary.

As there is no national unique health identifier in Ireland NDTRS data are episode based. Consequently, as each NDTRS episode relates to an episode of treatment rather than an individual, individuals may appear more than once if they return to treatment in a treatment service, or if treated in multiple services in any given year. The study population included all episodes who entered treatment for gambling in the period 2008–2019 (n = 2999). Gambling may have been the main reason for referral or recorded as an additional problem. Treatment episodes who reported gambling as their only problem (GO) were compared with those who reported gambling either as a main or secondary problem alongside additional problems (GA).

A combination of descriptive, exploratory statistics, and inferential analysis techniques were used to describe characteristics of episodes treated for gambling. Where data were normally distributed, mean scores and standard deviations were reported. Where data were skewed, median and interquartile ranges were reported. Data were managed and analysed in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, 2019). For all analyses, a p-value (two-tailed) of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Profile of episodes entering treatment

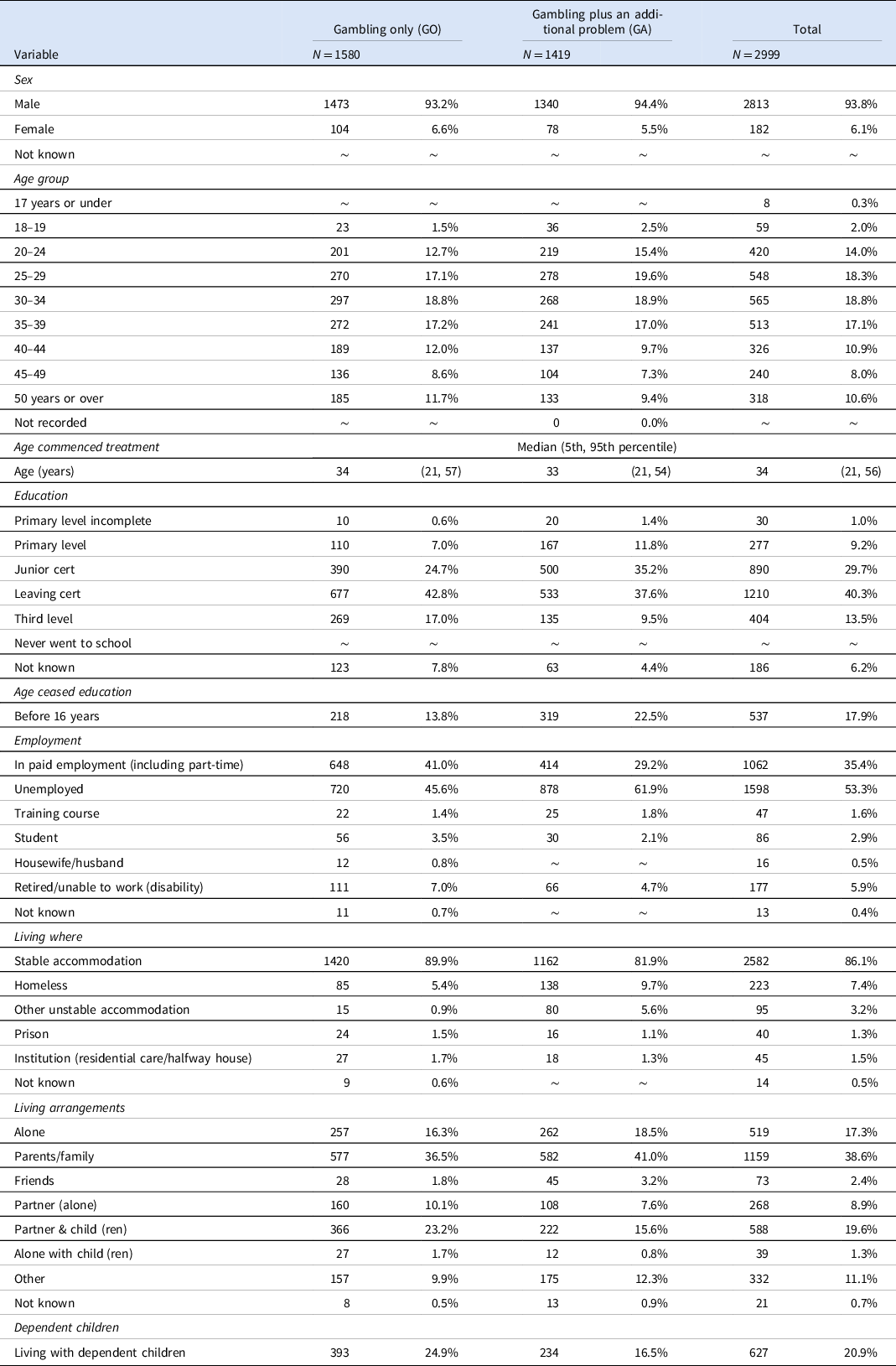

A total of 2999 episodes entered treatment for gambling during the period 2008–2019. More than half (1580 treatment episodes, 52.7%) reported gambling as their sole problem (GO), while 1419 treatment episodes (47.3%) reported problem gambling in combination with other problems (GA) (Table 1). The majority were male (93.8%). The median age entering treatment was 34 years and half of treatment episodes began gambling before they had reached their 17th birthday. The vast majority lived in stable accommodation (86.1%) and many lived with their parents/family (38.6%). One-fifth (20.9%) lived with dependent children. More than half had completed second or third level education (53.8%). One tenth (10.2%) of all treatment episodes had attained primary education only or less. Half of treatment episodes (53.3%) were unemployed, while 35.4% were in paid employment. Analysis by area of residence shows that 26.5% of all treatment episodes resided in CHO 4 (Kerry, North Cork, North Lee, South Lee, and West Cork) and 20.1% in CHO 5 (South Tipperary, Carlow/Kilkenny, Waterford and Wexford).

Table 1. Demographic profile of treatment episodes for problem gambling

∼ Cells with five episodes or fewer.

Treatment characteristics

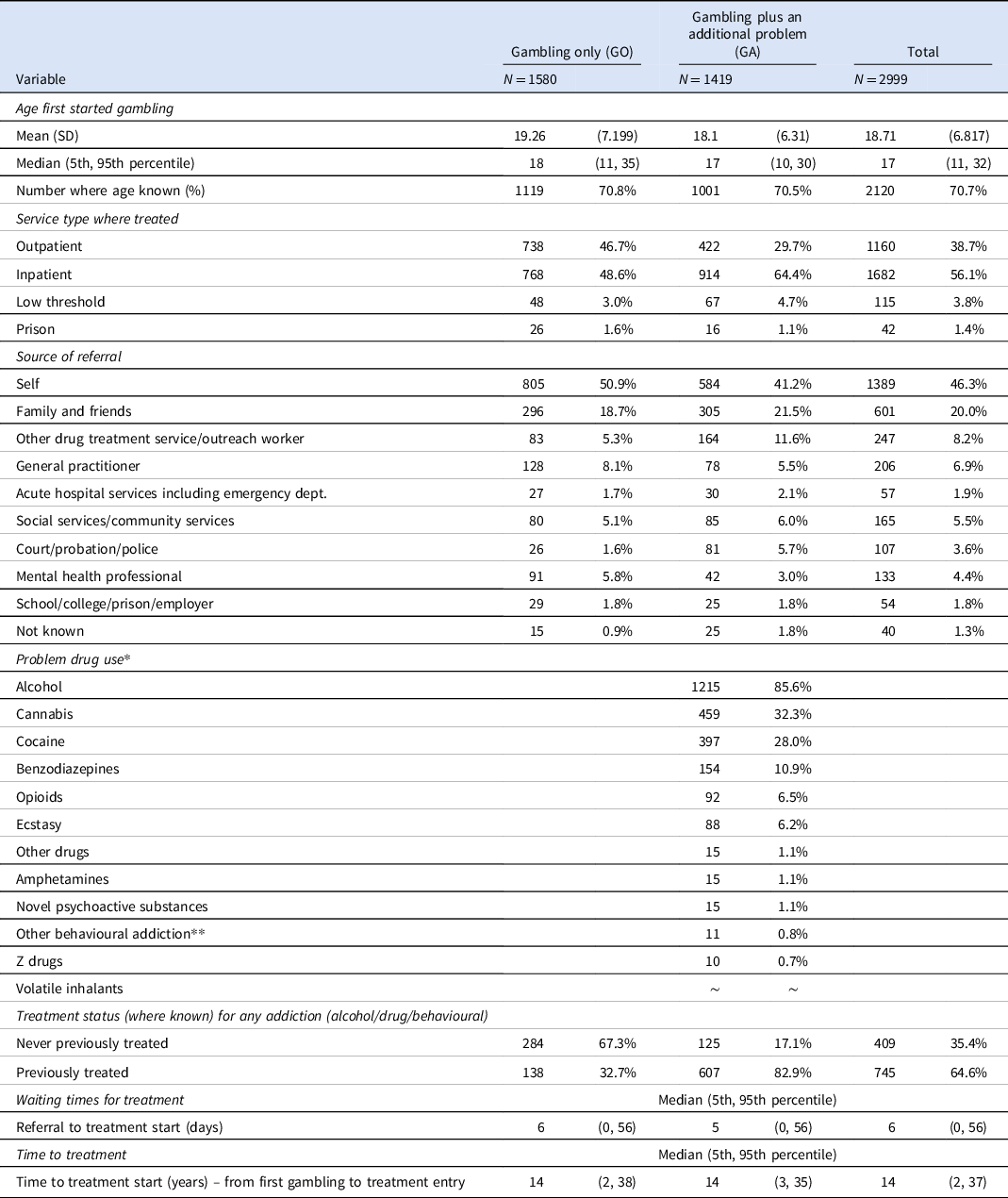

Treatment episodes primarily attended inpatient services (56.1%) or outpatient services (38.7%) for treatment, with smaller proportions accessing treatment via low threshold (3.8%) or prison services (1.4%). The most common source of referral was self-referral (46.3%), while 20.0% of referrals were from family/friends. Rates of treatment referrals by health professionals such as general practitioners (GPs) (6.9%) and mental health professionals (4.4%) were low. Almost half (47.3%) of all treatment episodes reported problem use of at least one drug. The most common problem drugs reported alongside gambling were alcohol (85.6%), followed by cannabis (32.3%), cocaine (28.0%) and benzodiazepines (10.9%). The median time between referral and treatment start was 6 days. A large proportion of treatment episodes (29.9%) were referred, assessed and started treatment all on the same day. The median time between first starting to gamble and commencing the current treatment episode was 14 years.

Differences between GO and GA treatment episodes

A higher proportion of GO treatment episodes lived with children (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Homelessness was more prevalent among GA treatment episodes (9.7%) compared to GO treatment episodes (5.4%) (p < 0.001). Unemployment was higher among GA treatment episodes (61.9%) than GO treatment episodes (45.6%) (p < 0.001). Conversely a higher proportion of GO treatment episodes (41.0%) were in paid employment compared with 29.2% of those with GA. Education attainment was higher among GO treatment episodes, 42.8% had completed the Leaving certificate and 17% had completed third level. A higher percentage of GA treatment episodes (22.5%) had left school prior to age 16 compared with GO treatment episodes (13.8%).

When compared with GO treatment episodes, GA treatment episodes were less likely to attend outpatient services (29.7%) and more likely to attended inpatient (64.4%) (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Referrals from GPs (8.1%) (p = 0.006) and from mental health professionals (5.8%) (p < 0.001) were higher among those presenting with GO. Those with GA were more likely to have been referred by the legal system (court/probation/police, 5.7%) (p < 0.001) or by another drug treatment service or outreach worker (11.6%) (p < 0.001) than GO treatment episodes.

Table 2. Treatment profile of treatment episodes for problem gambling

* Up to five problems may be reported.

** Other behavioural addictions include eating disorder, porn, sex.

∼ Cells with five episodes or fewer.

Discussion

The literature indicates that little is known about gambling behaviour in Ireland (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). This study is the first to report on problem gambling treatment episodes using routinely gathered national epidemiological data. Our findings indicate that episodes entering treatment for gambling are predominantly young men, who have gambled for long durations before seeking treatment, and many also reporting problem use of drugs alongside gambling. Treatment episodes had high levels of educational attainment, were living in stable accommodation, and the majority of whom attended for treatment in inpatient settings. The profile is not surprising as the most recently available Irish figures shows almost half of the population (49.0%) engage in gambling (Mongan et al. Reference Mongan, Millar, Doyle, Chakraboty and Galvin2022), with a prevalence rate for problem gambling among the general population at 0.3%, indicating that there are 12,000 people with problem gambling in Ireland (Mongan et al. Reference Mongan, Millar, Doyle, Chakraboty and Galvin2022).

Although in-person treatment for gambling may take place in outpatient or inpatient settings (College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, 2020), this study indicates that the majority of treatment, as reported to the NDTRS, takes place in inpatient settings (56.1%), with outpatient settings accounting for approximately one-third of treatment. NDTRS data show that treatment for gambling also occurs in both low threshold and prison settings, although this is rare. The low levels of treatment in outpatient settings in our study is surprising given that it is provided free of charge in the public health service (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). The literature indicates that inpatient treatment is often sought when outpatient treatment has been unsuccessful, or the problem is too severe to be effectively managed in the community (Passetti et al. Reference Passetti, Clark, Davis, Mehta, White, Checinski, King and Abou-Saleh2011). However, given the high levels of inpatient treatments observed in this study and that one-in-three (35.4%) treatment episodes had never previously received treatment (where treatment status was known), this may indicate the lack of availability of gambling treatment in outpatient settings and/or a preference for inpatient treatment among people who did seek treatment.

For treatment episodes reported to the NDTRS, results indicate that the demand for gambling treatment in Ireland is being met and met quickly. The median time from referral to treatment start was 6 days and therefore we can conclude that those who want treatment received it and that long waiting times are not a barrier to accessing treatment. However, it is estimated that as few as 7–12% of problem gamblers seek treatment (Slutske, Reference Slutske2006) and among those who do seek treatment, approximately half will leave treatment prematurely (Ronzitti et al. Reference Ronzitti, Soldini, Smith, Clerici and Bowden-Jones2017; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Murphy, Turner and Sharman2020). Therefore, there may be a considerable number of people in Ireland who would benefit from gambling treatment. There is a need to better understand what barriers are preventing people with problem gambling from accessing help. Our findings support previous reports highlighting the lack of dedicated referral pathways for treatment as a barrier to treatment access (Columb et al. Reference Columb, Griffiths and O’Gara2018). NDTRS data show that self-referrals and referrals by family or friends accounted for two-thirds of all treatment referrals, while rates of treatment referrals by health professionals including GPs and mental health professionals were extremely low, accounting for one-in-ten of all referrals. NDTRS data also show wide variations in geographical region of residence in our study which further supports earlier reports of treatment barriers due to differences or variations in the level of available service provision across healthcare regions (Columb et al. Reference Columb, Griffiths and O’Gara2018). This highlights the need for a more coordinated approach, with dedicated referral pathways and appropriate treatment services.

Existing research shows high levels of comorbidity or co-occurring conditions whereby gambling disorder is associated with co-existing psychiatric conditions including alcohol and other substance use disorders (Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, Cowlishaw, Jackson, Merkouris, Francis and Christensen2015; Lorains et al. Reference Lorains, Cowlishaw and Thomas2011; Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Welte, Tidwell and Hoffman2015). Therefore, it is not surprising that almost half (47.3%) of all gambling treatment episodes in our study reported problem use of at least one additional substance, with alcohol, cannabis and cocaine being the most commonly reported problem drugs reported alongside gambling. International rates indicate that 21% of treatment-seeking gamblers meet criteria for current alcohol use disorder (AUD) and 7% meet criteria of a current drug use disorder (DUD) (Dowling et al. Reference Dowling, Cowlishaw, Jackson, Merkouris, Francis and Christensen2015). By comparison, Irish rates reported in this study are higher with 40.5% receiving treatment for AUD and 26.7% receiving treatment for DUD. This is not unexpected as the majority of treatment episodes in this study were treated in an inpatient setting and the literature shows that those receiving treatment in inpatient settings have more severe gambling problems and report higher rates of co-morbid conditions than those being treated in outpatient services (Ladouceur et al. Reference Ladouceur, Sylvain, Sévigny, Poirier, Brisson, Dias, Dufour and Pilote2006).

It is possible that the profile observed in our study may be influenced by the person’s ability to acquire private health insurance and therefore access inpatient treatment, as many had a high level of educational attainment, were in employment and living in stable accommodation. The NDTRS includes data from both HSE addiction services and non-statutory service providers and is considered a comprehensive measure of treatment demand nationally (Bruton et al. Reference Bruton, Gibney, Hynes, Collins and Moran2021). The vast majority of services who participate in the NDTRS are public. In addition, a number of participating services (in particular inpatient services) are part-publicly funded, or places are funded through private health insurance. In which case, the NDTRS receives data for all treatments taking place in these services regardless of the funding stream. As funding stream is not recorded in the data, it is not possible to investigate the extent to which this may influence the profile of treatment entrants observed in this study.

Previous Irish legislation (Gaming and Lotteries Act 1956) allowed children aged 16 years and upwards to enter licensed gaming premises. This legislation set the legal age for purchasing lottery tickets or placing bets with a bookmaker at 18 years of age, however, there was no minimum legal age for placing Tote bets at racecourses or greyhound tracks. On 1 December 2020, the Gaming and Lotteries (Amendment) Act 2019 came into effect which standardised the minimum age for all forms of betting at 18 years. The potential impact of gambling on children is apparent in our study. Half of all treatment episodes entering treatment for problem gambling had started to gamble before they reached their 17th birthday, with 5% commencing gambling before their 11th birthday. Although a small number of children sought treatment in Ireland for problem gambling, the potential wider impact of parental gambling on children is evident with one-fifth of all treated gamblers living with dependent children. Among those with gambling as their sole problem as many as one-in-four lived lived with children. Research shows that harmful gambling among young people is also associated with co-dependencies, usually alcohol and other drugs (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Monitoring and surveillance via the NDTRS can play a key role in measuring the successful efforts to reduce the harm of gambling resulting from legislative changes.

There are hidden populations of gamblers and barriers to treatment. The proportion of gamblers who recognise that they need treatment and also take the step of seeking treatment is low (only 3–12%) (Slutske, Reference Slutske2006; Suurvali et al. Reference Suurvali, Hodgins, Toneatto and Cunningham2008). Treatment seeking varies by type, setting (e.g. land based, online), and severity (Blaszczynski et al. Reference Blaszczynski, Russell, Gainsbury and Hing2016; Columb & O’Gara, Reference Columb and O’Gara2018).

Barriers to treatment include lack of information about the nature and scale of the problem, the absence of specific public health approach or policies regarding gambling, along with the system or lack therefore of for dealing with referrals (Columb et al. Reference Columb, Griffiths and O’Gara2018; Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). The occurrence of a crisis (such as financial, emotional and sometimes legal difficulties) commonly precedes treatment seeking (Fulton, Reference Fulton2019), therefore those who have not yet experienced crisis are less likely to seek treatment.

Future studies should utilise existing multi-source national level datasets and appropriate methodologies to compare gambling rates in the general population with gambling treatment seekers (for example (Mongan et al. Reference Mongan, Carew, O’Neill, Millar, Lyons, Galvin and Smyth2021)). Such work would help estimate the size of the potential population that may need gambling treatment, the percentage of problem gamblers who actually access treatment and also explore whether certain subgroups are more or less likely to enter treatment. Findings will be important for policy, including the provision of treatment and targeted educational/awareness campaigns.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths. There is a paucity of research on gambling disorder in Ireland (College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, 2020), and this is the first analysis to describe the demand for gambling treatment over twelve years from national treatment data. Data on treated gambling episodes from the NDTRS provides valuable information which allows services and policymakers understand the extent of the problem, the personal and substance-using characteristics of episodes seeking treatment, and trends in treatment seeking over time. NDTRS data can enable health service planners to allocate appropriate resources to the treatment of problem gambling. The NDTRS is based on a standardised European treatment demand protocol, a harmonised methodology for drug treatment data collection, enabling international comparisons. Expanding such existing systems to include addictions such as gambling and other behavioural addictions, in addition to being cost effective, will inform and facilitate national and international efforts on such issues.

This study has a number of limitations which need to be considered when interpreting the findings. Population characteristics may not generalise beyond the treatment seeking population. Within the NDTRS it is possible that individuals may appear more than once if they are treated in different services or if they return to treatment in the same service within the same calendar year. In the absence of a national unique health identifier it is not possible to accurately distinguish between treatment episodes and individuals. As the NDTRS is based on the addiction treatment cohort, we cannot take into account those with non-problematic gambling, people who ceased to gamble or those who have not sought treatment. Despite high levels of service provider participation in the NDTRS (Health Research Board, 2017), not all services participate. In addition, reporting of problem gambling by service providers to the NDTRS is currently on a voluntary basis and may also explain the low numbers. Private counsellors who may provide outpatient addiction treatment do not participate in the NDTRS. There are no public health specific gambling treatment services in Ireland (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Nonetheless, a 2021 report by Kerr et al., identified 18 charity, voluntary and private organisations providing treatment for gambling in Ireland (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Twelve of these organisations fall within NDTRS remit, of which 75% returned data to the NDTRS in 2019. This indicates that although the number of NDTRS episodes for gambling may appear relatively small, coverage in the NDTRS of known service providers providing inpatient treatment for gambling in Ireland is high.

Recommendations

A number of harmful gambling practices have developed in Ireland due to the liberal attitude towards gambling and social stigma associated with problem gambling (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Much needed gambling legislation has yet to be enacted and population wide responses to gambling harms are scarce (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Therefore, improved awareness among both the public and healthcare professionals regarding the harms and consequences of gambling is important. Early intervention, screening and detection by healthcare professionals have been shown to be effective in reducing gambling related behaviours (Robson et al. Reference Robson, Edwards, Smith and Colman2002), however this is currently lacking in Ireland. Gambling specific expertise among health professionals is also lacking (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021) and gambling specific training is required for health professions. Strengthening of existing links between outpatient and inpatient treatment services, along with dedicated referral pathways are needed to alleviate treatment access barriers, enhanced public treatment provision and improve treatment uptake and treatment outcomes. A national coordinated approach could help minimise barriers due to regional variations in service provision.

Research into the most effective treatment environments has been previously recommended (College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, 2020). The literature states that once treatment is complete, there is no standardised means to assess treatment outcomes (Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, O’Brennan and Vazquez Mendoza2021). Routinely collected NDTRS treatment outcome data has the potential to provide much needed insights which can inform improved resource allocation and treatment service provision.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into treated problem gambling. Monitoring and surveillance can play a crucial role in measuring successful efforts and help inform planning and treatment. The findings may have implications for treatment pathways.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2022.20.

Acknowledgements

The Health Research Board provided the dataset used in this study. The authors would like to thank the Health Research Board, the NDTRS team and all the services who provide NDTRS data.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: SL, AMC and IC; Analysis and interpretation of data: IC and AMC; Drafting of the manuscript: IC, AMC, and SL; Critical revision: AMC and SL. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose. The analyses presented here used routinely collected and anonymised data; study-specific consent was, therefore, not required.