Evidence from randomised controlled trials has shown that periconceptional folic acid supplementation reduces the incidence of neural tube defects (NTDs) by 72%Reference Lumley, Watson, Watson and Bower1 and observational studies have shown that dietary folate is also protectiveReference Werler, Shapiro and Mitchell2–Reference Bower and Stanley6. In Australia, there have been two approaches to health promotion aimed at reducing the incidence of NTDs by increasing folate intake. The first involves population health-promotion programmes encouraging women to take folic acid supplements periconceptionally and to increase their dietary intake of folate-rich foods. The second has been legislative change to allow voluntary fortification of foods with folic acid.

In Western Australia (WA), from 1992 to 1995, we ran a health-promotion programme promoting folate to prevent NTDs based on the recommendations of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia7. The programme encouraged women of childbearing age to increase their dietary intake of folate and to take supplements of 500 μg folic acid daily for at least one month before pregnancy and the first three months of pregnancy. Women with a close family history of NTDs were advised to take 5 mg of folic acid daily. Information was distributed widely to health professionals and women, and increases in the knowledge and practice of women and health professionals have occurred as a result of the programmeReference Bower, Blum, Ng, Irvin and Kurinczuk8–Reference Bower, Knowles and Nicol11. Women's knowledge of the association between folate and spina bifida increased from 8% before the programme began to 67% two-and-a-half years later. The proportion of women taking periconceptional folic acid supplements increased from 13% to 30% over the same periodReference Bower, Blum, O'Daly, Higgins, Loutsky and Kosky10, Reference Marsack, Alsop, Kurinczuk and Bower12. Since 1995, some promotion of periconceptional use of folic acid supplements has continued in WA and other states and some national promotion has been undertakenReference Abraham and Webb13.

In 1995 voluntary folate fortification of specified foods was approved for the first time in Australia and since then there has been a gradual increase in the number of foods fortified. In 1999, over 100 foods were reported to be fortified with folate and available to consumers (mainly breakfast cereals, fruit juice, milk and special diet foods)Reference Abraham and Webb13.

Since the introduction of these measures in WA, there has been a fall in NTDs. The prevalence of NTDs (births plus terminations) in WA was about two per 1000 births from 1980 until 1995, and fell by 30% from 1996Reference Bower, Ryan, Rudy and Miller14.

The objective of the present paper is to report, using data collected from a random sample of recently pregnant women in WA, how many women were aware of folate fortification and labelling on foods that mentioned folate, and their consumption of fortified foods.

Methods

The data presented here relate to 578 women who had a live-born baby without birth defects in WA in 1997–2000. These women formed the control group of a larger case– control study, the methods of which have been reported elsewhereReference Bower, Miller, Payne, Serna, de Klerk and Stanley15, Reference Werler, Bower, Payne and Serna16 and are summarised briefly here.

A random sample of all live-born infants in WA was selected using the Midwives' Notification System as a sampling frame. This system is a statutory collection of data on all births ≥ 20 weeks' gestation in WAReference Gee17. Sampling was conducted from this sampling frame every month and was based on births in the previous month, using a sampling fraction such that we would have a final sample size of approximately 700 eligible controls. Mothers who did not speak English or were Aboriginal were ineligible for inclusion, as interpreters were not available, and the study methods were not culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people.

Data collection

A letter of invitation, with an information sheet about the study, a pregnancy questionnaire and a quantified food-frequency questionnaire, were sent to all eligible mothers 3–4 months after the birth of their child. Participating mothers returned completed questionnaires in the reply-paid envelope provided. Follow-up of non-responders was by telephone or by post. A short questionnaire covering knowledge of folate, and intake of vitamin supplements and fortified foods, but excluding the food-frequency questionnaire, was offered to mothers who felt that they did not have time or were not able to complete the full questionnaires.

Information collected from the long and short questionnaires included: awareness of the main health message about folate and spina bifida and timing of awareness of this messageReference Bower, Miller, Payne, Serna, de Klerk and Stanley15; and awareness of folate fortification measured as (1) awareness of folate added to foods, (2) knowledge of folate labelling of foods and (3) how often labels were read. We measured the proportion of women who noticed any labels on foods that mentioned folate, whether they were aware that folate was added to foods, how often they read the labels on foods and packaging, what foods they were aware of that had folate added to them, if they ate folate-fortified food, and if so, how much of the fortified food was eaten in the six months before their recent pregnancy. An increasing number of folic-acid-fortified foods came onto the market over the study periodReference Abraham and Webb13, Reference Lawrence, Rutishauser and Lewis18, and so the list of specific branded foods included in the questionnaire was updated at intervals.

We estimated the average weekly dietary intake of folate-fortified foods in the six months before pregnancy in servings of fortified foods. Serving sizes were defined according to the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating Reference Smith, Kellett and Schmerlaib19. For example, 2 slices of bread equals a bread serving, 1⅓ cup of breakfast cereal equals a cereal serving and 1 cup of milk (250 ml) equals a milk serving. The mean average weekly number of servings of folate-fortified foods that were eaten in the six months before pregnancy was determined by multiplying the number of months prior to the recent pregnancy that the food was eaten by how often the food was eaten per week multiplied by four and the number of servings per eating occasion. This total was then divided by 26 to determine the mean number of servings consumed per week over the previous six months. In addition we estimated, in servings per week, the intake of breads, cereals and milk (fortified and unfortified) consumed in the six months prior to the recent pregnancy from a modified 135-item food-frequency questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made using basic frequencies, the χ2 test for trend, Student's t-test and analysis of variance in SPSS Release 11.0.0 (SPSS Inc., 1998–2001). A mean, standard error and F-test were calculated and significance is given. Not all women answered all questions, so each analysis was based on all available data for the variables involved.

Results

Of the control mothers in the study 724 were eligible and invited to participate, and 578 agreed (79.8%). Non-responders were significantly more likely to be younger, unmarried, a public patient, to smoke during pregnancy, and have either no previous births or more than two previous births, when compared with responders. There was no difference between responders and non-responders with respect to infant sex or plurality, or maternal place of residenceReference Bower, Miller, Payne, Serna, de Klerk and Stanley15. Of women surveyed 88.9% were aware of the main folate message (the link between folate intake and prevention of birth defects such as spina bifida). Overall 62.3% of women were aware of the correct message of the association between folate and spina bifida before they became pregnant, 11.1% became aware during pregnancy and 26.7% were unaware of the association before or during pregnancy.

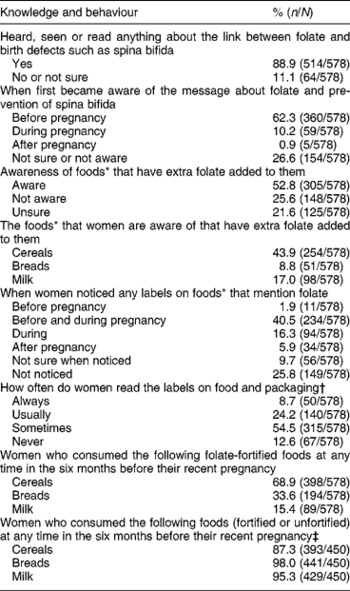

Of the women surveyed, 47% were not aware or were unsure that folate was added to foods available in Australia. However, 74% had noticed folate labelling, most commonly on breakfast cereals, breads and milk (Table 1). Forty-two per cent of women noticed folate labelling before their recent pregnancy, while 16% noticed it only during their pregnancy. In the six months before pregnancy, folate-fortified foods (cereals, breads or milk) were consumed by 78% of women (n = 451/578), with 69% consuming fortified cereals, 34% consuming fortified breads and 15% consuming fortified milk. Of those who ate fortified foods the mean number of servings per week of cereals consumed was 4.5, of bread was 8.2 and of milk was 9.2 (Table 2).

Table 1 Knowledge and behaviour of the total number of women surveyed

* Available in Australia; not aware or unsure = 47.2%.

† To see what nutrients or additives the food contains.

‡ The balance of subject responses are missing as food-frequency questionnaires were completed for n = 450.

Table 2 Of those women who consumed fortified foods, the mean number of servings consumed per week in the six months prior to recent pregnancy

* 78% ate one or more fortified food types (n = 451/578).

Based on all women surveyed who completed the dietary questionnaire (n = 450), cereals, bread or milk (fortified or not fortified) were consumed by 99% (444) of women. Of these women, 87% ate any cereal, 98% ate any bread and 95% drank milk.

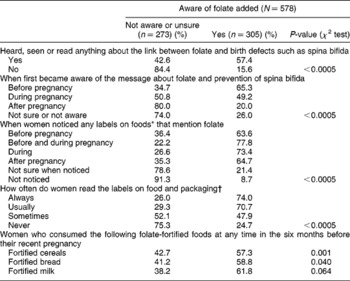

Women who were aware that folate was added to foods were more likely to have heard, seen or read anything about the link between folate and birth defects, were more likely to have first become aware before pregnancy of foods that mention folate than women who were not aware of foods that mention folate (Table 3), were more likely to have noticed (at any time) labels on foods that mentioned folate, and were more likely to usually or always read labels on food and packaging. They were also more likely to have eaten fortified cereals, fortified bread and fortified milk in the six months before becoming pregnant.

Table 3 Women aware of folate added to foods in association with when they became aware of folate-fortified foods, when they noticed any labels on foods that mention folate and how often they read labels on food and packaging†

* Of foods available in Australia.

† To see what nutrients or additives the food contains.

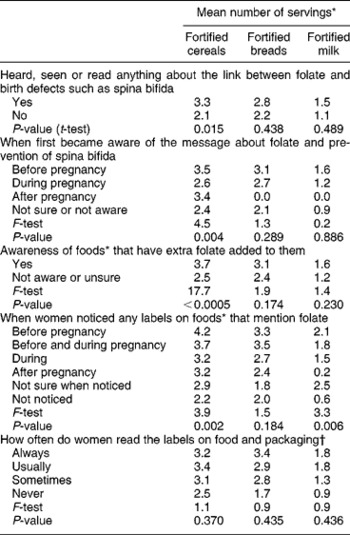

Of the 78% of women who ate folate-fortified foods, those who had heard, seen or read anything about the link between folate and birth defects such as spina bifida ate more servings of folate-fortified cereals, breads and milk per week in the six months prior to their recent pregnancy (significant only for cereals, P = 0.015) than those who had not heard, seen or read anything about the link. The earlier women became aware of the folate message, the more fortified cereals, breads and milk they consumed (significant only for cereals, P = 0.004) (Table 4). The intake of servings of folate-fortified cereals, breads and milk was greater with greater awareness of foods that have extra folate added (significant only for cereals, P < 0.0005). Furthermore, the earlier women noticed folate labelling, the more fortified cereal servings (P = 0.002), bread servings (P = 0.184) and milk servings (P = 0.006) were consumed prior to or during their recent pregnancy. The mean number of servings of fortified cereals, breads and milk was greater, but not significantly so, the more often women read the labels on food and packaging (Table 4).

Table 4 The mean number of servings of folate-fortified foods consumed per week in the six months prior to recent pregnancy (of those women who consumed fortified foods) by awareness of folate fortification and labelling

* Of folate-fortified foods consumed per week in the six months prior to recent pregnancy using a list of specific branded foods fortified with folic acid.

† Of foods available in Australia.

Discussion

We showed that between 1997 and 2000, 62.3% of women in this study were aware before becoming pregnant of the protection against spina bifida of extra folate intake before pregnancy, 53% were aware that foods available in Australia have extra folate added to them, and 42% noticed folate labelling on foods before or during their recent pregnancy. Folate-fortified cereals, breads or milk were consumed by 78% of women. Those women who were aware that folate was added to foods were more likely to have been aware of folate and to have noticed that foods were fortified with folate before their recent pregnancy. The earlier women became aware of the folate message or noticed any labels on foods that mentioned folate, the more servings of folate-fortified cereals were consumed.

In a previous study in the same cohort of womenReference Bower, Miller, Payne and Serna20 we showed that efforts to increase folate intake through health-promotion strategies aimed at changing individual behaviour did not reach all women equally, whereas the structural health-promotion strategy of folate-fortified foods increased folate exposure and intake equally across the target group. Because folate fortification in Australia is voluntary, only about half the women in the cohort (57%) were getting more than 100 μg daily from fortified foods. We therefore concluded that mandatory fortification of a staple food may be likely to reach all women regardless of demographic characteristics and health-related behaviours. Based on the results presented in the current paper, 98% of women consumed bread (fortified or unfortified), suggesting that bread (or flour) would be an appropriate vehicle for mandatory folate fortification in Australia, as it is in the USA and CanadaReference Honein, Paulozzi, Mathews, Erickson and Wong21, Reference Ray, Meier, Vermeulen, Boss, Wyatt and Cole22.

There was high participation in our study (79%) but non-responders were more likely to be young, unmarried, not to have private health insurance, to smoke during pregnancy, and have either had no previous births or more than two previous birthsReference Bower, Miller, Payne, Serna, de Klerk and Stanley15. With the exception of women with two or more previous births, all of these characteristics were associated with a greater risk of not knowing the correct message and not taking periconceptional folic acid supplementsReference Bower, Miller, Payne and Serna20. Thus, the proportion of the population unaware of the correct message and not taking supplements may be greater than our study indicates. Further, the retrospective assessment of awareness and intake of fortified foods as well as timing of awareness of these may be a limitation of our study due to poor memory or inaccurate recall.

It is possible that the association between awareness of existence of folate-fortified foods, labelling and consumption is causal, but it is not possible to determine the direction of causation. Although knowledge of the health link, followed by awareness of fortified foods and increased consumption is consistent with the knowledge –behaviour theory of behaviour changeReference Egger, Donovan and Spark23, the direction of causation may well have been in the opposite direction. Those purchasing and eating fortified foods may not have purchased or eaten the food because it was fortified but may have become aware of folate fortification and the health message due to package labelling. We did not ask women if they had purposely chosen fortified foods in order to increase their folate intake.

Despite sociodemographic differences in knowledge of the link between folate and prevention of spina bifida, which we have previously reportedReference Bower, Miller, Payne and Serna20, there were no such differences between women who did and did not consume fortified products. In the current analysis only half the women knew that folate was added to foods and yet 78% ate at least one fortified food.

A study from Victoria, Australia found that, in 2000, 50% of women were aware that some foods had folate added to them and 34% nominated ready-to-eat cereals as being fortifiedReference Watson, Watson, Bell and Halliday24. These percentages are similar to those found in our study of 53% and 44%, respectively. Further, in other studies in Australia that took place around the time of our study there was an increase in women's knowledge of folate but no increase in sales of ready-to-eat breakfast cereals carrying a health claim about folateReference Watson and Watson25.

In order to achieve an increase in intake of folate for the prevention of NTDs, it is generally agreed that strategies other than periconceptional folic acid supplementation are required, because even with active health promotion of supplement use, it is difficult to achieve greater than 50% of women taking supplements at the relevant time. Furthermore, there are significant socio-economic differences in use of supplementsReference Bower, Miller, Payne and Serna20, Reference Ray, Singh and Burrows26 and, in Australia, neither health promotion of folate nor voluntary fortification has affected the high rates of NTDs in Indigenous infantsReference Bower, Eades, Payne, D'Antoine and Stanley27.

Mandatory fortification of flour with folate has been introduced in many countries for the primary prevention of NTDs. The evidence for a benefit in preventing NTDs is clear, and other benefits have been suggested, but these need to be balanced against possible risks, particularly as the whole population is exposed to fortified foods, not just the target group of women of childbearing age. The risks include possible masking of vitamin B12 deficiency (especially in the elderly), an increased risk of twinningReference Lumley, Watson, Watson and Bower1 and potentiation of cancersReference Slattery, Curtin, Anderson, Ma, Edwards and Leppert28. While there is reassurance from countries that have instituted fortification with regard to the first two concernsReference Signore, Mills, Cox and Trumble29, Reference Liu, West, Randell, Longerich, O'Connor and Scott30, it is too soon yet to have sufficient data to address the theoretical concern about cancer promotion.

Fortification of staple foods has the potential to deliver increased folate to all women of childbearing age, regardless of socio-economic status or whether they planned their pregnancy, but the evidence from the present study shows that voluntary fortification, although reaching women more equitably and leading to a population increase in serum folateReference Hickling, Hung, Knuiman, Jamrozik, McQuillan and Beilby31, is not sufficiently widespread to be able to increase folate intake for all women. Furthermore, only about half the women knew about foods that were voluntarily fortified – most of these were breakfast cereals, corresponding to the fact that most voluntarily fortified foods in Australia are breakfast cerealsReference Abraham and Webb13. Thus, many women do not appear to actively choose fortified foods for the purpose of increasing their folate intake.

Mandatory fortification of flour or bread (or even milk) would passively increase intake above that achieved by voluntary fortification, as these are foods that are consumed by most women; indeed, in countries where mandatory fortification of flour with folate has been introduced, there have been significant falls in NTD ratesReference Honein, Paulozzi, Mathews, Erickson and Wong21, Reference Ray, Meier, Vermeulen, Boss, Wyatt and Cole22, Reference Lopez-Camelo, Orioli, da Graca Dutra, Nazer-Herrera, Rivera and Ojeda32. Mandatory fortification with 200–300 μg of folic acid per 100 g of wheat flour was approved in Australia and New Zealand in June 2007 and an extensive monitoring system is being finalised to determine the effects of mandatory folic acid fortification.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The Health Promotion Foundation of Western Australia (Grant #4912) funded this project. We also acknowledge financial support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Program Grant #003209; Fellowship #353625 (C.I.B.) and Fellowship #323204 (W.H.O.)).

Conflict of interest declaration: None of the authors has a conflict of interest in relation to the research reported in this paper.

Authorship responsibilities: W.H.O. conducted the analyses, contributed to interpretation of the results and drafted the paper; M.M. contributed to study design, advised on the dietary questionnaire and analysis and contributed to interpretation of the results; J.M.P. contributed to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results; P.S. contributed to data collection and interpretation of the results; C.I.B. designed the study, directed its implementation and contributed to analysis, interpretation of the results and writing the paper; and all authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful for the contribution of participants in the study, members of the Advisory Group for the study and Mrs Vivien Gee, Department of Health. Ethics and confidentiality approvals for this study were provided by the Princess Margaret/King Edward Memorial Hospitals Ethics Committee (#716) and the Confidentiality of Health Information Committee for the Department of Health in Western Australia (#97 004).