Organizations may have periods of crisis causing high levels of uncertainty and deleterious consequences for their profits and performance (Coombs, Reference Coombs2014; Dean, Reference Dean2004). Crises arouse anxiety, as both employees and stakeholders are afraid to be harmed (Ayoko, Ang, & Parry, Reference Ayoko, Ang and Parry2017; Jin & Pang, Reference Jin, Pang, Coombs and Holladay2010). Under crisis conditions, perceptions of the organization may as a result drastically suffer and be deflated, possibly leading to loss of loyalty and trust from employees and other stakeholders (Hegner, Beldad, & Kamphuis op Heghuis, Reference Hegner, Beldad and Kamphuis op Heghuis2014; Jones, Jones, & Little, Reference Jones, Jones and Little2000). It is therefore important to understand which factors protect organizations against such negative perceptions that can be caused by crisis.

Although previous research has identified several factors involved in effectively managing organizational crises (Coombs, Reference Coombs, Coombs and Holladay2010; Kahn, Barton, & Fellows, Reference Kahn, Barton and Fellows2013; Marsen, Reference Marsen2020; Rosenthal, Boin, & Comfort, Reference Rosenthal, Boin and Comfort2001; Wei, Ouyang, & Chen, Reference Wei, Ouyang and Chen2017), further work still needs to be carried out to isolate specific features of organizations and employees that may serve this end. Perceptions of organizations in crisis are intertwined with perceived organizational identity (i.e., what is perceived to define the organization, which is the anchor for organizational identification; Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg, Hogg, Ferris, Johnson and Sedikides2018) and features of organizational identity may thus influence the effects of a crisis on perceptions of the organization. Surprisingly, however, the role of features of organizational identity during a crisis has been neglected by the organizational crisis literature. The main aim of the present research is to fill this void by approaching organizational crisis through the lens of the social identity approach to organizations (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000; van Knippenberg, Reference van Knippenberg, West, Tjosvold and Smith2003), and arguing that processes involved in protecting social identity may influence the effects of organizational crisis on employee perceptions of the organization. Importantly, this should hold to the extent that they identify with the organization (i.e., which ties features of organizational identity to one's self-definition), because self-definition tied to organizational membership would motivate protecting their sense of identity in the face of organizational crisis.

We propose that organization sector prototypicality (i.e., the extent to which an organization is perceived to embody the prototypical – identity-defining – characteristics of its market sector) is an influential factor in shaping employee perceptions of the organization in crisis, and more so the more members identify with the organization. Note that the concept of prototypicality is intended here at an organization level of analysis, where it is understood not to refer to the prototypicality of individual members of a group, as is more typically the case (Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000), but the prototypicality of an organization as a member of a category of organizations (i.e., market sector). As central parts of their market sector, prototypical organizations are likely to be perceived as able to efficiently cope with crises as a result of identity-protection mechanisms. The more the organization is perceived to ‘embody’ the market sector (i.e., being prototypical of the sector), the less likely it is perceived to fail, because its potential failure would be more strongly tied to the sector as a whole. This is a conclusion that organization members are eager to avoid because of identity-protection mechanisms (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worehel1979). We propose that this effect is stronger the more the employees identify with the organization, because it is identification that elicits the motivation to protect one's self-image as it is tied to the group's image.

Negative effects of organizational crisis

Crises have been described as ‘specific, unexpected, and non-routine event[s] or a series of events that create high levels of uncertainty and threaten or are perceived to threaten an organization's high priority goals’ (Seeger, Reynolds, & Sellnow, Reference Seeger, Reynolds, Sellnow, Heath and O'Hair2009, p. 233). The threatening nature of crises can produce uncertainty, preoccupation, and anxiety (Bundy & Pfarrer, Reference Bundy and Pfarrer2015; Jin & Pang, Reference Jin, Pang, Coombs and Holladay2010), which may have negative effects on the perception of organizations' reliability, accountability, and survival (Dean, Reference Dean2004; Yu, Sengul, & Lester, Reference Yu, Sengul and Lester2008). Consistent with this, it has been suggested that crises are largely perceptual, meaning that the stakeholders' expectations and perceptions play an important role in the effectiveness of crisis management (Penrose, Reference Penrose2000). However, improving perceived organizational effectiveness within a crisis cannot be properly done without considering the organizations' characteristics as well as stakeholders' and employees' psychological factors.

Along those lines, previous research has shown that a good reputation is an essential factor in buffering the decline of the organization's market value in times of corporate crisis (Jones, Jones, & Little, Reference Jones, Jones and Little2000). In particular, though being well-known (a sub-dimension of organizational reputation) can be a burden, generalized favorability buffers the negative effects of crisis (Wei, Ouyang, & Chen, Reference Wei, Ouyang and Chen2017). Under high uncertainty, a firm's generalized favorable reputation directly influences stakeholders' perceptions and decision-making. This is because under these conditions stakeholders rely on past attitudes to evaluate and interpret the crisis situation (Bundy & Pfarrer, Reference Bundy and Pfarrer2015; Gwebu, Wang, & Wang, Reference Gwebu, Wang and Wang2018). Conversely, because well-known organizations are subjected to especially intense scrutiny, being a well-known organization may have boomerang effects (Zyglidopoulos, Georgiadis, & Carroll, Reference Zyglidopoulos, Georgiadis and Carroll2012). Therefore, as during a firm's crisis negative information is generally more salient and accessible, it may negatively affect firm perceptions.

Causal attribution of crisis' responsibility is another factor involved in the effects of crisis (e.g., Schwarz, Reference Schwarz2008). A recent study has shown that the less the stakeholders tend to attribute the responsibility for the crisis to the firm, the lower are their negative perceptions of the firm (and vice versa; Mason, Reference Mason2019). Trust has also been found to be a critical factor in promoting firm efficacy, efficiency, and productiveness, serving as a buffer during a crisis (Hegner, Beldad, & Kamphuis op Heghuis, Reference Hegner, Beldad and Kamphuis op Heghuis2014). Other scholars have shown that organizational preparedness and positive stakeholder relationships may facilitate crisis management after a triggering event (Ulmer, Reference Ulmer2001).

Overall, evidence suggests that firms' reputation and preparedness, causal attribution of responsibility for the crisis, and members' trust in the organizational capacities are factors in buffering the negative effects of crisis. However, research in this field has been silent so far on the organizational identity characteristics that may help buffer the negative effects of organizational crisis. This is unfortunate, as research has demonstrated that organizational identity characteristics strongly determine employees' perceptions, judgments, and behavior, especially when organizational threat is made salient (as in the case of crisis), and employees strongly identify with their organizations (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011). Building on the social identity approach (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Haslam, Reference Haslam2004; Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2001; van Dick, Reference van Dick, Cooper and Robertson2004; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg, Hogg, Ferris, Johnson and Sedikides2018), our aim was to investigate the neglected role of identity characteristics of organizations involved in a crisis.

Social identity approach to organizational crisis

The social identity approach, comprising social identity theory (SIT) and self-categorization theory (SCT; Haslam, Reference Haslam2004, Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008; Stets & Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worehel1979; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987; van Dick, Reference van Dick, Cooper and Robertson2004), describes how individuals' self-concept in part derives from their membership of a social group. Broadly speaking, SIT suggests that to the extent that individuals identify with a social group, they derive their self-definitions from group membership (i.e., social identity). Individuals who identify with a group are motivated to protect or enhance the image of their group, in order to protect or enhance their self-esteem that derives from it (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worehel1979). According to SCT, social groups are categorized through the lens of prototypes (i.e., cognitive structures that include typical beliefs, values, and behavior associated with the social group), which give order to social reality and function as reference point for group members (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987). The self-categorization process (i.e., categorization of self as a member of a social category) leads to conformity to the ingroup prototype, to perceive other ingroup members as sharing the group's prototypical characteristics, and to positively evaluate them (Stets & Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987).

In the last few decades, the above premises have been applied to organizational settings (e.g., Haslam, Reference Haslam2004; Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2001; van Dick, Reference van Dick, Cooper and Robertson2004). Research has suggested that organizational identity is a particular form of social identity referring to individuals' membership of an organization (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Haslam, van Knippenberg, Platow, & Ellemers, Reference Haslam, van Knippenberg, Platow and Ellemers2003; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg, Hogg, Ferris, Johnson and Sedikides2018). Accordingly, where an organizational identity is salient for members, it exerts influence on a variety of organizational behaviors (Hogg, Reference Hogg2000; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg and Hogg2003). For instance, organizational identification leads employees to exert extra efforts for the organization to achieve higher performance (Hekman, van Knippenberg, & Pratt, Reference Hekman, van Knippenberg and Pratt2016; van Knippenberg, Reference van Knippenberg2000) and lowers turnover intentions (Abrams, Ando, & Hinkle, Reference Abrams, Ando and Hinkle1998; van Dick et al., Reference van Dick, Christ, Stellmacher, Wagner, Ahlswede, Grubba and Tissington2004; see Lee, Park, & Koo, Reference Lee, Park and Koo2015, for a meta-analytic review). Importantly, prior research has shown that members perceived to embody to a greater extent the prototypical characteristics of a social group (i.e., the group prototype) are more positively evaluated by other ingroup members, as they help define the group as a whole (Hogg, Cooper-Shaw, & Holzworth, Reference Hogg, Cooper-Shaw and Holzworth1993). This insight has also been applied to organizational leadership to argue that group prototypical leaders (i.e., leaders that are perceived to embody the group's prototype) are more influential because they are perceived to embody the core group characteristics that group members share and conform to (Hogg, van Knippenberg, & Rast, Reference Hogg, van Knippenberg and Rast2012; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg and Hogg2003). The tendency to conform to group prototypical characteristics helps reduce the epistemic uncertainty about the group identity; this is the reason why prototypical leaders are so effective (Pierro, Cicero, Bonaiuto, van Knippenberg, & Kruglanski, Reference Pierro, Cicero, Bonaiuto, van Knippenberg and Kruglanski2005). As group membership becomes more salient, and the identification with the ingroup stronger, prototypical leaders become more effective (Hogg, van Knippenberg, & Rast, Reference Hogg, van Knippenberg and Rast2012; Ullrich, Christ, & van Dick, Reference Ullrich, Christ and van Dick2009; van Knippenberg, Reference van Knippenberg2011; for meta-analytic reviews see Barreto & Hogg, Reference Barreto and Hogg2017; Steffens, Munt, van Knippenberg, Platow, & Haslam, Reference Steffens, Munt, van Knippenberg, Platow and Haslam2021).

This work regarding group prototypicality was conducted at the individual level, but these insights can also be applied to organizations as economic actors – that is, at the organization level (e.g., Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011; Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2001). Prototypes are cognitive concepts that can be applied to social categories at any level of abstraction with similar implications for category membership. That is, just like individuals can be perceived in terms of social categories (e.g., their work organizations), work organizations can be perceived in terms of social categories (e.g., their market sectors). From this follows that work organizations may embody to a different degree the prototypical characteristics of their category (i.e., market sector) – organizations differ in how prototypical they are of their market sector (i.e., organization sector prototypicality). Similarly, just like group prototypical leaders are seen as more effective by group members, especially when members strongly identify with their group, we may expect organizations prototypical of their market sector to be perceived as more effective by their members, especially when members strongly identify with their organization. Also important for our investigation is research showing that it is especially under conditions of group's threat and uncertainty that factors linked with the group's membership play a critical role, and exert stronger effects on individuals' cognitions and behaviors (Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000).

Therefore, we could reasonably think that these factors may play an important role during organizational crises. As organizational threat and uncertainty increase during a crisis, organizations can be perceived by their members as being less able to achieve satisfactory levels of performance compared a situation without crisis. However, the organization's sector prototypicality, in combination with members' identification with the organization, may buffer against such negative organizational performance perceptions. This is the focus of the current study.

We argue that organizations perceived to be more prototypical of their market sector are more protected from negative perceptions as a result of a crisis situation. As an organization's sector prototypicality means being perceived to possess and embody the core characteristics of its market sector, psychologically there is a motivation to see the organization as not failing in facing the crisis, because failure would reflect negatively on the sector as a whole (i.e., because the organization is central to it). We propose that this is why organization members, especially those who strongly identify with the organization, will positively evaluate its capacity to cope with crisis. In other words, we argue that organization sector prototypicality is a factor buffering against the negative effects of crisis, especially for employees that more strongly identify with their organization.

Present research

The aim of the present research was to examine whether the negative effects of perceived organizational crisis can be buffered by specific organizational identity characteristics. Based on the social identity approach, we expect that under crisis conditions, when uncertainty and threat are high (Coombs & Holladay, Reference Coombs, Holladay, Ashkanasy, Zerbe and Hartel2005; Jin & Pang, Reference Jin, Pang, Coombs and Holladay2010), organization sector prototypicality works as a protective factor by reducing threat and uncertainty inherent to the crisis. Therefore, organizations perceived to be more prototypical of their market sector will be perceived as more able to face the crisis, especially by employees that more strongly identify with the organization. Thus, we hypothesized that the negative effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance would be reduced (buffered) by the perceptions of being part of an organization with higher (vs. lower) sector prototypicality:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived organizational crisis has a negative relationship with perceived organizational performance that is weaker the higher the perceived sector prototypicality of the organization.

Moreover, we expected that this interactive effect is stronger for employees identifying more strongly with the organization:

Hypothesis 2: The interactive effect of perceived organizational crisis and perceived sector prototypicality on perceived organizational performance is stronger with higher employee organizational identification.

We conducted two studies to test these hypotheses, as described in the next sections. The first study was an experiment to test hypothesis 1. The second study is a survey to test both hypotheses.

Study 1

The aim of study 1 was to test whether organization sector prototypicality buffers the negative effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance (hypothesis 1). We tested this hypothesis in an experimental scenario study with participants who could be potential employees of the organization. Participants were invited to imagine that they were working for an international consulting company, which was chosen as a typical company that students of social, organizational, and clinical psychology (the participants in the study) could imagine as their future workplace (Pierro et al., Reference Pierro, Cicero, Bonaiuto, van Knippenberg and Kruglanski2005).

Method

Participants

Two hundred nineteen participants (both recent graduate and current psychology students from Sapienza University of Rome; 106 women; M age = 25.06, sdage = 1.75) took part in the study on a voluntary basis. Most of the sample had a bachelor (51.1%) and master (45.2%) degree; the rest of the sample had high school graduation (1.4%) or missing data (2.3%).

Design

To test our hypotheses, organizational crisis (high vs. low), and organization sector prototypicality (high vs. low) were manipulated between participants in four different scenarios. The dependent variable was participants' perception of organizational performance. All materials were presented in Italian after careful translation of source materials. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions.

Procedures and measures

Participants were asked to take part in a study about organizations. A paper and pencil questionnaire was handed out in the Faculty of Psychology, at Sapienza University of Rome, between May and June 2008. They were invited to imagine they were working for an international consulting company, and were asked to imagine the described situation as realistically as possible. After a short introduction, participants read the organization sector prototypicality manipulation (adapted from van Knippenberg and van Knippenberg, Reference van Knippenberg and van Knippenberg2005).

The low prototypical organization was described as having little in common with other consulting organizations with a different culture, history, and vision compared with other organizations of its sector. The high prototypical organization was described as being very similar to the other consultancy organizations, with a culture, history, and vision similar to that of other consultancy organizations (see Appendix 1).

Following the prototypicality manipulation, five items adapted from Platow and van Knippenberg (Reference Platow and van Knippenberg2001) and van Knippenberg and van Knippenberg (Reference van Knippenberg and van Knippenberg2005) to measure organization sector prototypicality were presented: ‘This organization is a good example of the organizations that belong to the consulting sector’; ‘This organization has much in common with the organizations of the consulting sector’; ‘This organization embodies the typical characteristics of the organizations that belong to the consulting sector’; ‘This organization is very similar to other organizations of consulting sector’; and ‘This organization resembles the organizations that belong to consulting sector.’ Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert type scale (from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘strongly agree’). The average of the scale served as manipulation check of organization's sector prototypicality (α = .96).

Subsequently, participants read the organizational crisis scenario, which was created for this study and focused on the organization's financial condition (positive vs. negative), inspired by a real-life case. In the non-crisis scenario, the organization was described as experiencing a positive financial situation because of cost reduction, weak competition due to the lack of new low cost offers, good customer management with a subsequent low rate of refund requests, and fair cost of salaries and directors' liquidation. The organization was attempting to improve profitability, and the organization management was achieving goals to enhance profit. In the high crisis scenario, the organization was described as going through a crisis because of increased costs, competition due to new low cost offers, slightly higher salaries and directors' liquidation, and a poor customer management with a subsequent high rate of refund requests. The organization was attempting to pay off debts and to minimize loss (see Appendix 2).

Subsequently, participants responded to the following four items: ‘My organization is in crisis,’ ‘The situation of my organization is problematic,’ ‘The situation of my organization is worrying,’ and ‘The current situation will bring improvement to my organization’ (this item's scores were reversed). Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert type scale (from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘strongly agree’). The average of these items served as manipulation check of organizational crisis (α = .84).

After reading the scenarios, perceived organizational performance was measured by the following four items, derived and adapted by Hackman (Reference Hackman and Lorsch1987) and De Dreu (Reference De Dreu2007): ‘My organization is good in coming up with ways to complete its tasks’; ‘My organization possesses the competence to effectively achieve its aims’; ‘My organization uses its own knowledge and competence in an effective way’; and ‘My organization is very effective in carrying out its tasks.’ Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert type scale (from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘strongly agree’). The average of these items served as the dependent variable (α = .93). The final section of the questionnaire included three items on socio-demographic data (gender, age, and educational qualification).

Results

Manipulation checks

Organization sector prototypicality

Participants assigned to the high prototypicality scenario perceived the organization as more prototypical of its market sector (M = 5.52, sd = 1.08) than participants assigned to the low prototypicality scenario (M = 2.84, sd = 1.50), t(1, 217) = 15.50, p < .001. This indicated that our organization sector prototypicality manipulation was effective.

Organizational crisis

Participants assigned to the high organizational crisis scenario perceived the organization as being more in crisis (M = 5.38, sd = .95) than participants assigned to the low organizational crisis scenario (M = 2.68, sd = 1.12), t(1, 217) = 19.07, p < .001. This indicated that that our organizational crisis manipulation was effective.

Perceived organizational performance

To test hypothesis 1, a 2 (organizational crisis) × 2 (organization sector prototypicality) between-participants analysis of variance was performed, controlling for participant age and gender. No effects of participant age and gender were found, F(5, 213) = .97, p = .33, pη 2 = .005; F(5, 213) = .27, p = .61, pη 2 = .001, respectively.

As expected, a negative effect of organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance, F(5, 213) = 64.39, p < .001, pη 2 = .23, and a positive effect of organization sector prototypicality on perceived organizational performance, F(5, 213) = 10.62, p = .001, pη 2 = .05, were found. Most important, and in line with hypothesis 1, was the interaction of organizational crisis and organization sector prototypicality, F(5, 213) = 3.70, p = .056, pη 2 = .02.

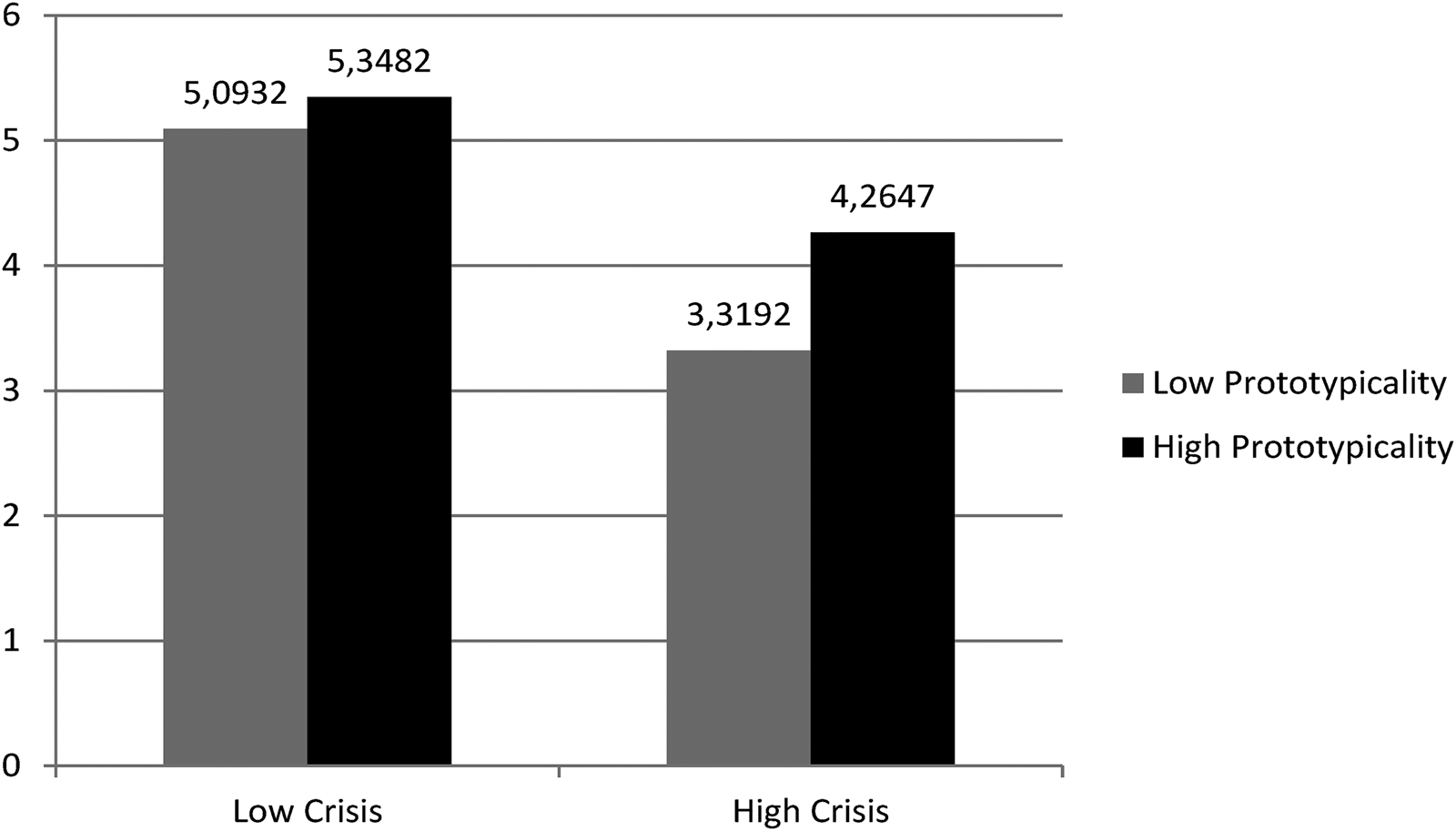

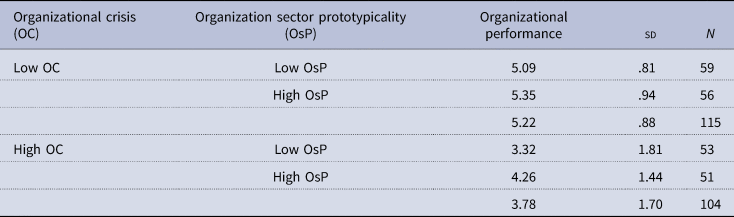

Simple effects analyses revealed that the predicted negative effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance was significant for participants assigned to the low organization sector prototypicality scenario (M = 3.32, sd = 1.81; M = 5.09, sd = .81, high and low crisis scenarios, respectively), t(215) = −7.25, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.26. As predicted, the negative effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance was substantially smaller for participants assigned to the high organization sector prototypicality scenario (M = 4.26, sd = 1.44; M = 5.35, sd = .94; high and low crisis scenarios, respectively), t(215) = −4.33, p < .001, Cohen's d = .09 (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1. Perceived organizational performance as a function of organizational crisis and organization sector prototypicality (study 1).

Table 1. Perceived organizational performance as a function of organizational crisis (X) and organization sector prototypicality (M) (study 1)

Furthermore, in the low crisis scenario, perceived organizational performance did not significantly differ between high and low organization sector prototypicality scenarios (M = 5.35, sd = .94; M = 5.09, sd = .81, respectively), t(215) = −1.06, p = .29, Cohen's d = .03. However, as expected, under the high crisis condition, perceived organizational performance was significantly higher for participants assigned to the high (vs. low) organization sector prototypicality scenario (M = 4.26, sd = 1.44; M = 3.32, sd = 1.81, respectively), t(215) = 3.73, p < .001, Cohen's d = .06, showing that the negative effect of the perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance was buffered by high (vs. low) organization sector prototypicality.

Discussion

The findings of study 1 provide support for the prediction that when an organization is perceived as prototypical of its market sector, it can buffer the negative effects of organizational crises (hypothesis 1). This is because prototypicality makes the organization seem more effective by helping to reduce the uncertainty that is enhanced under crisis conditions. This is consistent with previous research showing that group prototypical leaders are perceived as more effective under uncertainty conditions (Cicero, Pierro, & van Knippenberg, Reference Cicero, Pierro and van Knippenberg2007, Reference Cicero, Pierro and van Knippenberg2010; Pierro et al., Reference Pierro, Cicero, Bonaiuto, van Knippenberg and Kruglanski2005).

However, in this study a scenario design was used and the focus was not on actual employees. Although useful for a first test of hypothesis 1, this inevitably presents some limitations, as participants may not be highly involved in the hypothetical scenario. In order to overcome this limitation, in study 2 we tested hypothesis 1 in the context of a real company facing an actual crisis, and a measure of employee identification with the organization was added for a test of hypothesis 2.

Study 2

The aim of study 2 was twofold. The first aim was to provide another test of hypothesis 1 in the context of a real organization facing a crisis with a sample of real employees. The second aim was to test whether the negative effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance is buffered by the organization sector prototypicality primarily for employees who more strongly identify with the organization (hypothesis 2).

Method

Participants

Two hundred sixty-four employees (133 women; M age = 39.11; sdage = 8.54) of the Italian national airline company (Alitalia) took part in the study. On average, participants had been working for this company for 154.61 months (i.e., a bit more than 13 years; sd = 103.72; seven participants did not report this data), with different job positions: 5.7% were managers/professionals, 49.9% were white collar workers, 35.6% were pursers or flight attendants, and 16.3% were pilots (2 participants, .8%, did not report this data). In total, 34.5% of the participants had a bachelor or master degree; the rest of the sample had a high school (60.5%) or middle school (4.6%) education (1 participant, .4%, answered ‘prefer not to say’).

Design

To test the hypotheses, perceived organizational crisis, organization sector prototypicality, and organizational identification were measured. The dependent variable was perceived organizational performance. Gender and age were measured as control variables. All materials were in Italian with careful translation of source materials.

Procedure

Data were collected with a paper and pencil questionnaire during the official period of financial crisis that struck Alitalia between October and November 2008, as the result of a long period of management problems and political instability. Participants were contacted directly at the ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ airport in Fiumicino (Rome) and in two main offices in Rome, in order to involve both flight attendants and office workers.

Measures

Organizational crisis

Perceived organizational crisis was measured using the same four items as study 1 (α = .77).

Organization sector prototypicality

Organization sector prototypicality was measured using the same scale as study 1 (adapted for Alitalia's market sector). The reliability of this measure was good (α = .90).

Organizational identification

Organizational identification was measured by the following six items derived from Mael & Ashforth (Reference Mael and Ashforth1992) and van Knippenberg and van Schie (Reference van Knippenberg and van Schie2000): ‘When my organization is criticized, it feels like a personal insult’; ‘I am very interested in knowing what others think about my organization’; ‘When I talk about my organization I usually say “we” rather than “them”’; ‘My organization's successes are my successes’; and ‘If a news from the media would criticize my organization, I'd feel uncomfortable.’ Participants responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (α = .89).

Perceived organizational performance

Perceived organizational performance was measured by the same four items as study 1 (α = .67).

The fit of each scale in confirmatory factor analysis was satisfactory: perceived organizational crisis (χ2(2, N = 264) = 7.07, p < .05; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .10; SRMR = .02); organization sector prototypicality (χ2(5, N = 264) = 35.95, p < .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .15; SRMR = .03); organizational identification (χ2(9, N = 264) = 11.74, p = .22; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .02); and perceived organizational performance (χ2(2, N = 264) = 9.59, p < .01; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .12; SRMR = .04). Factor loadings of each latent variable were statistically significant (p < .001) and above .45, suggesting the unidimensionality of each scale.

Results

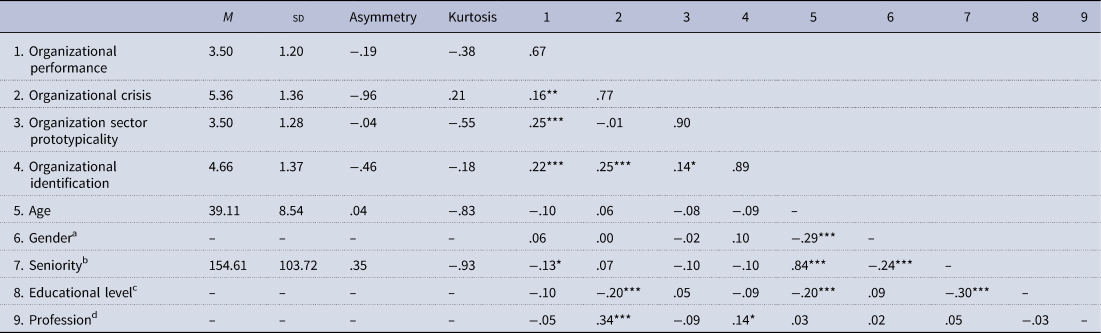

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of all study variables are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Means, sd, reliabilities, and correlations between the variables (study 2)

a Gender coded: 1 = male and 2 = female.

b Seniority coded in months of employment.

c Educational level: 1 = middle school, 2 = high school, 3 = bachelor/master degree or more.

d Profession: 1 = managers and white collars and 2 = flight attendants and pilots.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

To test predictions, a moderated multiple regression analysis, using PROCESS statistical software (model 3; 5,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, Reference Hayes2013) was conducted. The independent variables (i.e., X = perceived organizational crisis, M = organization sector prototypicality, and W = employee identification) were mean-centered. As in study 1, participant age and gender were controls. The overall multiple regression model was significant, R 2 = .22, F(9, 254) = 8.11, p < .001. No significant effects of age and gender were found (β = −.01, t(254) = −1.14, p = .26; β = .14, t(254) = .99, p = .33, respectively).

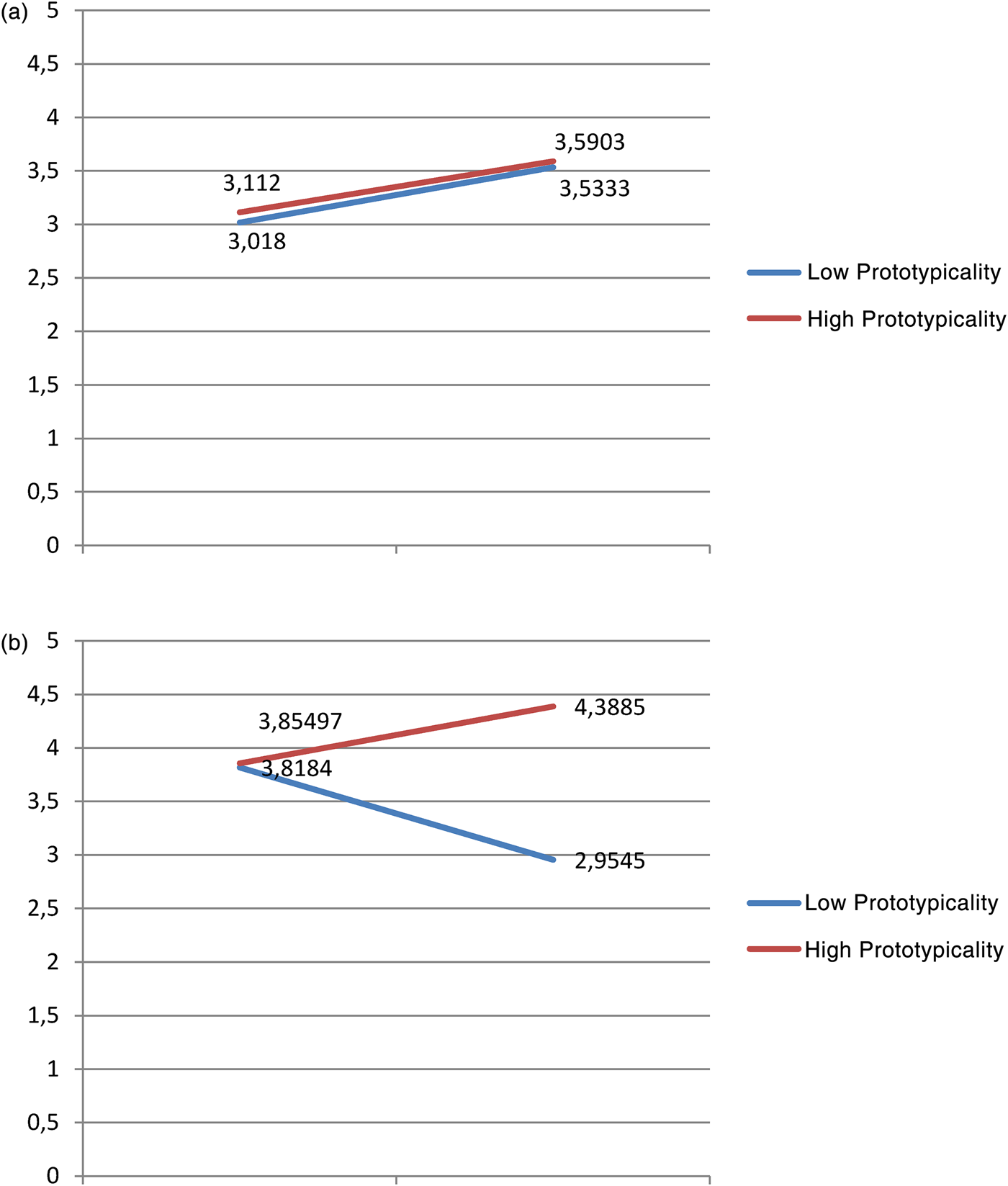

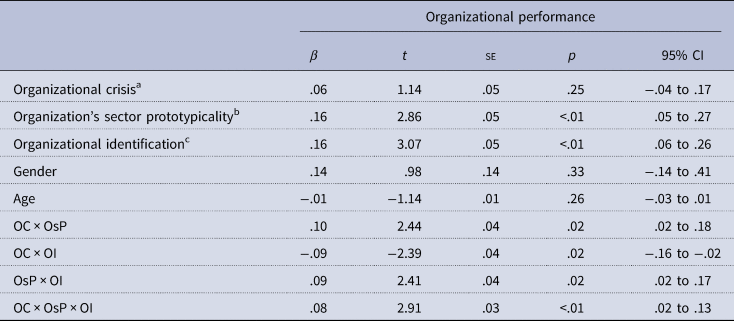

The main effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance was not significant (β = .06, t(254) = 1.14, p = .25). Significant main effects of organization sector prototypicality (β = .16, t(254) = 2.86, p = .005) and employees' identification (β = .16, t(254) = 3.07, p = .002) were found. The two-way interactions between (1) perceived organizational crisis and organization sector prototypicality (β = .10, t(254) = 2.45, p = .02); (2) perceived organizational crisis and employee identification (β = −.09, t(254) = −2.39, p = .02); and (3) organization sector prototypicality and employee identification attained statistical significance (β = .09, t(254) = 2.41, p = .02). More importantly, the predicted three-way interaction of perceived organizational crisis, organization sector prototypicality, and employee identification was significant (β = .08, t(254) = 2.91, p < .01); see Table 3. Figures 2A and 2B display the interaction graphs.

Figure 2. (A) Low employees' identification (1 sd below the mean). Perceived organizational performance as a function of organizational crisis and organization sector prototypicality (study 2). (B) High employees' identification (1 sd above the mean). Perceived organizational performance as a function of organizational crisis and organization sector prototypicality (study 2).

Table 3. Summary of moderated regression analyses (study 2)

a OC, organizational crisis.

b OsP, organization's sector prototypicality.

c OI, organizational identification.

Note: Gender coded: male = 1; female = 2.

An analysis conducted to further clarify the nature of the three-way interaction (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991) revealed that the interaction effect between perceived organizational crisis and organization sector prototypicality was significant for more strongly identifying employees (β = .20, t(254) = 3.19, p = .002) but not for more weakly identifying employees (β = −.005, t(254) = −.13, p = .90). As expected, the simple slope analyses revealed that for strongly identifying employees the predicted negative effect of perceived organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance was significant for lower levels of organization sector prototypicality (1 sd below the mean: β = −.32, t(254) = −2.92, p < .01); however, this effect was attenuated by higher levels of organization sector prototypicality (1 sd above the mean: β = .20, t(254) = 1.62, p = .11). Furthermore, as expected, the effect of organization sector prototypicality on perceived organizational performance was significant for higher levels of perceived organizational crisis (1 sd above the mean: β = .56, t(254) = 6.21, p < .001); however, this effect was reduced by lower levels of perceived organizational crisis (1 sd below the mean: β = .01, t(254) = .09, p = .93). Thus, the three-way interaction shows that, for strongly (vs. weakly) identifying employees, the negative effect of organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance was reduced by high (vs. low) levels of organization sector prototypicality.

Discussion

The findings of study 2 are important as they (1) confirm the buffering role of the organization sector prototypicality in the negative effect of organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance (hypothesis 1), generalizing it to a real organizational context on a sample of real employees; (2) provide evidence of the hypothesized moderating effect of employee identification with the organization (hypothesis 2). More specifically, the findings of study 2 showed that organization sector prototypicality buffers the negative effect of crisis on perceived organizational performance, especially for employees that more strongly (vs. weakly) identified with their organization.

General discussion

The present research aimed to assess the possible role of variables derived from the social identity approach to organizational behavior in buffering the negative effects of organizational crisis on perceived organizational performance. We proposed that organization sector prototypicality would be a relevant factor under crisis conditions, especially for strongly identifying employees, as it helps them to perceive their organization as being more able to cope with the crisis. Therefore, it was expected that employees of a more (vs. less) market sector prototypical organization would perceive their organization as more able to cope with the crisis (hypothesis 1), particularly when they strongly (vs. weakly) identify with it (hypothesis 2). Findings of the two studies confirmed the hypotheses on both potential and real employees (albeit the role of identification only in study 2), respectively using a scenario experimental design and a real crisis situation.

More specifically, in study 1 participants read a scenario in which a consulting company was undergoing a financial crisis (vs. a non-crisis condition) and the company was described as highly (vs. lowly) prototypical of its market sector. After reading the scenario, participants were asked to answer questions about the firm's perceived performance. In accordance with previous research on organizational crisis (Coombs, Reference Coombs2014; Dean, Reference Dean2004), results showed that the higher the crisis, the lower the perceived organizational performance. However, consistent with our predictions, the negative effect was significantly reduced by organization sector prototypicality: the higher the perceived organization sector prototypicality, the less crisis negatively impacts performance perceptions.

In study 2 we asked employees (flight attendants and office workers) of a real organization (Alitalia) facing a period of very strong financial crisis to fill out a questionnaire during the crisis period. Consistent with our main hypothesis, the negative effect of the perceived crisis on perceived organizational performance was reduced (buffered) when the organization was perceived as more (vs. less) prototypical of its market sector (airlines), especially for more strongly identifying employees. These findings make two main theoretical contributions. First of all, this research is the first investigation on whether and how organizational identity features influence perceptions of organizations during crises. Although previous research has shown that organizational identity features may largely influence how employees and stakeholders perceive their organization, no study so far investigated whether and how these variables may influence organizational perception during crisis. With this aim in mind, we approached organizational crisis through the lens of the social identity approach to organizations (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; Haslam, Reference Haslam2004; Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2001; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg, Hogg, Ferris, Johnson and Sedikides2018). We proposed and found that organization sector prototypicality, that is the extent to which an organization is perceived to be central in defining its market section, positively influence perceptions of organizational performance during a crisis, especially for its highly identifying employees because they are more sensitive to its prototypicality as it helps to reduce the uncertainty aroused by the crisis. This is due to the fact that a prototypical organization is perceived as less likely to fail as it defines its market sector with its features. This encourages employees to be positive about their organization's capacity to cope with the crisis, thus reducing uncertainty levels, consistently with the idea that prototypicality is not only an essential feature for individual effectiveness within a group (as for leaders; Pierro et al., Reference Pierro, Cicero, Bonaiuto, van Knippenberg and Kruglanski2005; Steffens et al., Reference Steffens, Munt, van Knippenberg, Platow and Haslam2021; van Knippenberg & Hogg, Reference van Knippenberg and Hogg2003), but also for organizations' effectiveness within their own market sectors. This last point is of particular interest as it represents the second main theoretical contribution of the present investigation. The present research extends previous work on the social identity approach to organizations by conceptualizing the prototypicality construct at an organizational level (i.e., organization being prototypical of its market sector), and by demonstrating that such prototypicality helps buffer against the negative effects of organizational crisis. More specifically, although the concept of prototypicality usually refers to individual members of a group (e.g., leader group prototypicality), in the present research we considered it at a higher level of abstraction, that is, the prototypicality of an organization as a member of a category of organizations (i.e., market sector). This construct, defined at this level of abstraction, is particularly important during a crisis by helping to perceive organizations as able to efficiently cope with crises, as a result of identity-protection mechanisms. As the organization is perceived to ‘define’ its market sector with its prototypical characteristics, the organization is perceived more able to cope with a crisis because its potential failure would be more strongly tied to the sector as a whole. This is a conclusion that organization members, especially those strongly identifying with it, are eager to avoid because of identity-protection mechanisms (Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worehel1979).

On a practical level, the present research suggests that organizations may buffer against the negative effects of crisis on how their employees view the organization by building a sense of the organization as prototypical of its market sector because this builds employee confidence in the organization's ability to weather the crisis. Research in organizational identity and organizational change has established that perceptions of organizational identity are fluid and can be influenced by organizational leadership's identity narratives – organizational leadership's advocacy of an understanding of organizational identity (i.e., talking about ‘who we are as a company’; e.g., Gioia and Chittipeddi, Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991; see van Knippenberg, Reference van Knippenberg, Pratt, Schultz, Ashforth and Ravasi2016, for a review; also see Reicher and Hopkins, Reference Reicher, Hopkins, van Knippenberg and Hogg2003, for a similar argument concerning political leadership). Along similar lines, organizational leadership may advocate an understanding of organizational identity and the organization's market sector that suggests that the organization is prototypical of its market sector. In essence, this boils down to ascribing the same identity-defining attributes to the organization as to the sector as whole (e.g., a customer first mentality, a focus on continuous improvement, etc.). Although this notion of identity narratives does not mean that ‘anything goes’ and there is skill involved in doing this well, the work we draw on here suggests that there is sufficient ambiguity around organizational identity (and by implication presumably around market sector identity) to leave room for such leader sense-giving efforts (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Reference Gioia and Chittipeddi1991) to shape perceptions of organizational and sector identity. Importantly, such organizational identity rhetoric ideally would not just be a matter of internal (i.e., employee-focused) communication, but also it can be focused on external stakeholders (e.g., through marketing efforts and other forms of corporate communication). A key reason for this is that employees also operate in that external environment and their image of the organization is shaped and reinforced by how external stakeholders perceive the organization (Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, Reference Dutton, Dukerich and Harquail1994).

In addition, our findings suggest that such efforts to build a sense of organizational identity as prototypical of its market sector are more effective at buffering against negative effects of crisis the more employees identify with the organization. This suggests that efforts to build organizational identification can be integral to preemptively position the organization to weather a crisis. To some extent, such efforts revolve around leader sense-giving. More positive and distinct organizational identities are more likely to inspire identification (Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, Reference Dutton, Dukerich and Harquail1994). Accordingly, leader identity narratives that include claims to the organization's positive and distinct qualities (and thus also the positive qualities of the sector, as per the above) would be integral to effectively building a sense of organizational identity that positions the organization well to confront a potential crisis as far as its effects on employee perceptions are concerned.

The present work also has its limitations that raise important questions for future research. We argued that uncertainty aroused by crisis conditions would be reduced by organization sector prototypicality, especially for more strongly identifying individuals. We did, however, not assess the assumed mediating variables of uncertainty (inspired by crisis) and trust in the organization's capabilities to weather the crisis (as inspired by sector prototypicality). Future research replicating and extending our work by including such measures would thus be valuable in bolstering the confidence in our conclusions.

Another potential mechanism of the buffering effects of organization sector prototypicality and employee organizational identification might be attribution of responsibility. Previous research has largely shown that the internal causal attribution of crisis (i.e., the company being held responsible for the organizational crisis) negatively influences firm value and stakeholder perceptions of the firm (Coombs, Reference Coombs2007). It is possible that highly prototypical organizations may reduce perceived organizational responsibility for the crisis, and especially for more strongly identifying employees. This could also (help) buffer the negative impact of crisis. This is a possibility that could also be explored in future research.

A further potential direction is investigating whether the same buffering effects found on employees could be extended to the organization's external stakeholders (e.g., clients, business partners, shareholders). This would be highly relevant for organizations, as these actors are essential for organizational coping strategies in case of crisis (Dean, Reference Dean2004; Hegner, Beldad, & Kamphuis op Heghuis, Reference Hegner, Beldad and Kamphuis op Heghuis2014).

In conclusion, organizational crises involve uncertainty and threats that can have negative consequences for firm performance in part because it impacts perceptions of the organizations performance and thus potentially feeds into future trust in the organization, willingness to work for and with the organization, etc. (Coombs, Reference Coombs2014; Dean, Reference Dean2004). The current study shows that in understanding and managing such effects, it is valuable to adopt an organizational identity perspective and to consider how identity perceptions impact the effects of crisis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.