Nutrition is a daily challenge for the estimated 2·3 to 3·5 million individuals who are homeless each year in America( Reference Burt, Aron and Lee 1 ). The prevalence of food insufficiency is sixfold greater in the US homeless population than in the general population( Reference Baggett, Singer and Rao 2 ). At the same time, homeless individuals suffer disproportionately from nutrition-related diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia( Reference Jones, Perera and Chow 3 ). With a high burden of risk factors for malnutrition, such as alcoholism, drug use, mental illness and physical illness, improving the nutrition of homeless populations is of particular concern( Reference Wiecha, Dwyer and Dunn-Strohecker 4 ). Despite these realities, the nutrition of the homeless has received scant attention as a public health issue.

Homeless shelters and soup kitchens – social institutions prevalent in most major cities across the USA – serve as the primary food source for the majority of homeless individuals( Reference Wiecha, Dwyer and Dunn-Strohecker 4 – Reference Johnson and McCool 6 ). While shelters and soup kitchens traditionally serve as safety nets, rather than places to affect health, they have an untapped potential to impact food access, choice and quality. As such, they offer a concrete target for nutrition interventions for homeless populations.

No national standards exist for food served in shelters and soup kitchens. The nutritional quality of food served to homeless individuals in the USA is often of poor nutritional value. Studies have long demonstrated that shelter and soup kitchen meals have a high prevalence of inadequate or imbalanced nutrient, vitamin and mineral content( Reference Johnson and McCool 6 , Reference Strasser, Damrosch and Gaines 7 ). In Boston, for example, shelters commonly receive and serve an abundance of leftover pastries, pizzas and desserts donated by local restaurants. Recent evidence from San Francisco demonstrates that shelter meals are deficient in fibre, Ca, K and vitamins A and E, while containing excess fat( Reference Lyles, Drago-Ferguson and Lopez 8 ). Shelter and soup kitchen staff provide a critical service in providing for those in need, yet their ability to offer nutritionally adequate foods is often constrained by lack of resources.

The feasibility of leveraging shelters and soup kitchens for nutrition interventions has not been explored. To our knowledge, no study has assessed the current practices or attitudes of shelter staff members, who would be instrumental in endorsing and implementing improvements in shelter nutrition. Thus, we conducted 60 min, in-person interviews with shelter or soup kitchen food directors from ten shelters in the Greater Boston area. We interviewed a diverse sample of facilities in terms of size, location and demographic served. The lead study author conducted all of the interviews. The thirty-question survey was standardized across sites. It included open-ended and close-ended questions addressing current practices, barriers and ideas to improve the nutrition of homeless individuals (see online supplementary material).

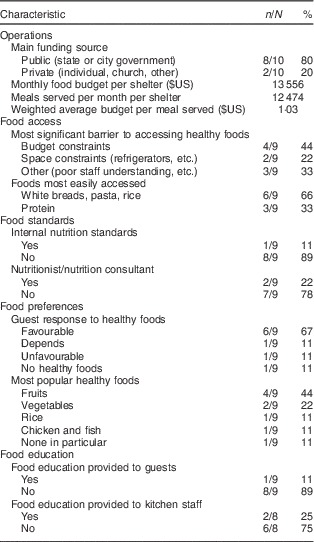

Our interviews generated the following main results (Table 1). The main funding source for most shelters and soup kitchens was public, including city and state government. On average 12 474 meals were served per month. The weighted average budget per meal served was $US 1·03. The most significant barrier to accessing healthy foods was budget constraints, followed by space constraints. The foods most easily accessed included white breads, pasta and rice. One out of nine shelters provided food education to guests and two out of eight provided food education to kitchen staff.

Table 1 Characteristics of shelters and soup kitchens in Greater Boston, MA, USA (N 10Footnote *)

* Several shelters did not respond to particular questions.

Our findings generated the following lessons. First, shelters and soup kitchens can improve food quality even within a constrained budget. For example, in one shelter in Massachusetts, staff worked within a $US 300 weekly food budget to substitute whole grain bread for white bread, 1 % milk for whole milk and nuts for pastries. With the help of a local food-rescue organization, the shelter also secured a weekly donation of fruits and vegetables. In addition, six out of nine shelters and soup kitchens reported that guests responded favourably to healthier food options when available. If guests were initially resistant to the healthier foods, phasing them in over time was reported to be a useful strategy. Two shelters had benefited from working with a nutritionist to review menus for adequate nutrition. Additional ideas for improving food quality include that shelter staff can encourage donations of healthier foods rather than the common high-starch, high-sugar donations. In turn, corporate and community partners can be more aware to provide these healthier options.

Second, shelters and soup kitchens provide a convenient location for nutrition education. Previous studies have shown nutrition education programmes in shelters to be effective and well-received by homeless individuals( Reference Rodriguez, Applebaum and Stephenson-Hunter 9 ). In our Greater Boston sample, only one shelter currently engages in some type of nutrition education for guests, suggesting that additional opportunities for intervention are available. One form of nutrition education is simply providing the nutrition content of the meals on table tents, encouraging guests to consider and question their nutritional options. Educating shelter chefs and food providers about the nutritional needs of homeless people is also important, as the nutritional knowledge of homeless people can be put to little use if not given adequate options by providers.

Third, optimizing the shelter and soup kitchen environment to improve nutrition can be achieved at little cost. Evidence suggests that choice architecture – such as simply redesigning default options or making healthier choices more accessible – can change consumer behaviour without imposing rules( Reference Thaler and Sunstein 10 ). Shelters and soup kitchens can pay attention to how healthy food is displayed and make it more prominent than less healthy options. Another idea is a suggestion box to allow guests to voice their thoughts or ask questions about the food served, enabling them to be more invested in their food choices. Access to scales within the shelter is a further low-cost intervention that could help people monitor their weight status, encouraging guests to be more attentive to food choice.

Fourth, support for homeless shelters and soup kitchens from federal, state and local governments can make a meaningful impact. Funding could be earmarked for specific items, such as refrigerator and freezer space in shelters and soup kitchens – which was reported as a barrier to being able to store healthier perishable foods. Funding could also be used to more broadly address food quality or education. In New York City, for instance, Executive Order 122 enacted by former Mayor Bloomberg in 2008 implemented standards for foods purchased and served by city agencies, which included shelters and soup kitchens. The standards called for a minimum number of daily servings of fruits and vegetables, recommended whole grains, and required beverages to be 100 % fruit juice, water or low-fat milk. Furthermore, it precluded agencies from accepting donations of candy or sugar-sweetened beverages. To our knowledge, New York City is the only city that has enacted such standards in the USA. This example shows that while challenging, large-scale change is possible with support from policy makers.

In summary, our preliminary results suggest that improving the nutrition of homeless populations through shelters and soup kitchens is not only beneficial but also feasible. The main limitation of this work is its small sample size; however, its intended purpose was to gather initial impressions from a diverse group of shelters and soup kitchens in an urban setting with a high prevalence of homelessness.

The nutritional needs of the homeless have for too long received insufficient attention as a public health issue. It should be no longer acceptable to believe that simply providing calories to vulnerable individuals is enough. Instead, communities can shift the focus to the quality of these calories and to the environments providing them( Reference Koh, Hoy and O’Connell 11 ). Shelter and soup kitchen staff, community members and government agencies alike can work together to accomplish this goal. By improving food quality, education and policies in shelters and soup kitchens, we can help provide homeless individuals the dignity of opportunity to restore their health and quality of life.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are incredibly thankful to Claire Oppenheim, Leah Briggs, Ellen Anderson, Casey Leon, Stephen Paquin, Cynthia Bayerl, Dr Derri Shtasel, Dr Travis Baggett and Dr Jim O’Connell for their guidance and support for this work. They are also deeply grateful to the shelter and soup kitchen staff members who gave their time for this project and for the daily service they provide to individuals experiencing homelessness. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflicts of interest: None. Authorship: K.A.K. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted interviews, wrote the manuscript and edited the manuscript. M.B. helped to conceptualize the study and edit the manuscript. D.C.H. helped design the study, supervised the study and edited the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Partners Human Research Committee, the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015002682