Introduction

Professionals in public health and psychiatry held a joint meeting in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) on 13 December 2019. The meeting could not have been more timely. It anticipated great challenges in the century ahead and called for greater collaboration between these two areas of healthcare. The result was a renewed commitment to our shared goal of better population health. We recognised that a fresh perspective was needed, that healthcare in Ireland and around the world was at a crossroads and there were many challenges to address. How could current models of service delivery be sustained? How could our healthcare systems meet the unforeseen challenges that were to come? Where would the next generation of therapeutic progress come from?

The meeting agenda

Looking back at our agenda, it is clear that our meeting took place at the end of one clinical era without knowing that the next was just about to begin. History does not fit neatly into the Gregorian calendar (Hobsbawm, Reference Hobsbawm1989). One century of medicine does not end and another begin at the stroke of midnight. We did not know that within a few weeks the COVID-19 virus would emerge in China spreading quickly to Europe and around the world. COVID-19 was to become the biggest upset in population health in one hundred years. Now we know that the global pandemic marked the beginning of 21st century healthcare.

Our discussions were prescient still, even if we lacked specific knowledge of the virus. We knew that to prepare for the next era of healthcare, we must learn lessons from our shared experience of population healthcare in the past century. And we knew that we were better placed to do this together. Psychiatry and public health have been linked by the narrative of public policy and politics and by many challenges in our community and our environment. The agenda of our joint meeting could not have been more relevant.

How can our health services be sustained? – Economics lessons to be learned

Even before the pandemic, it was clear that our healthcare economics were in crisis. Spending by governments on healthcare is often represented as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Although spending is rising everywhere, this simple ratio tells us little about the national costs of our healthcare systems. Suppose that these costs were represented as a share of our total revenue. When we consider our spending as a proportion of our total income a clearer picture emerges.

Total healthcare spending in Ireland in 2018 was 22.5 Billion Euro (Public 17 Billion Euro; Private 5.5 Billion Euro). In the same year, our total revenue was roughly 50 billion Euro, and our total income tax revenue was 21 billion Euro. In other words, by 2018, our healthcare spending had reached a tipping point. Our costs each year amounted to more Euro than we earned in income tax in any year (CSO, 2021).

Rising costs are not the only challenge to the maintenance of our healthcare systems, human factors may be even more problematic. Shortage of human resource is a critical limiting factor in our service development. The scarcity of manpower in healthcare was already apparent long before the recent pandemic. In 2014, the WHO called on us to acknowledge the shortage of sufficiently skilled workforce and to recognise the impact of this deficit on the sustainability of our current healthcare models (WHO 2014). This problem became critical during the COVID-19 pandemic when the government made desperate calls for retired and migrant healthcare professionals to return to ‘the front line’. Although war time analogies were dramatically effective, they were not sufficient to illustrate the true scale and significance of these events. The COVID-19 crisis simply confirmed the facts. Current models of healthcare are unsustainable in either cash or human terms.

Making our healthcare system more effective? – Redefining the utilitarian principle

A renewed expression of Bentham’s utilitarian principle is needed. The obligation of healthcare is to do ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’. Michael Porter in Harvard has redefined this ideal as ‘value in healthcare’ and he expressed this value in the mathematical equation Q x S divided by C (where Q stands for quality and S for service and C is cost) (Porter & Teisberg Reference Porter and Teisberg2006). The successful adoption of this utilitarian parameter depends upon systems of healthcare genuinely capable of measuring these variables, but at least Porter has articulated a way forward. He has acknowledged the healthcare problem in modern utilitarian terms and gone some way to offering us hope of a solution.

Preparing for the challenges of the future – Lessons from public health

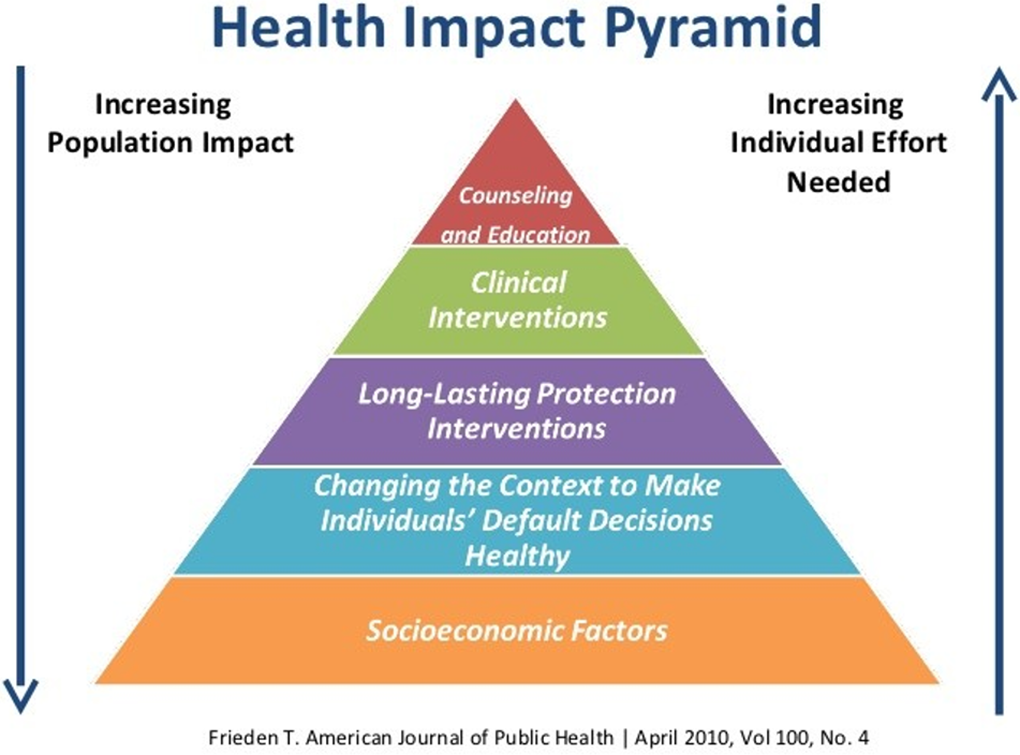

The Porter ‘Value Equation’ is all the more compelling since it resonates with our understanding of population health and mental health. The current imbalance is best illustrated by the work of Tom Frieden (the former director of the Centers for Disease Control, CDC, USA). He (Frieden Reference Frieden2010) used his health impact triangle to differentiate health investments of high population impact from those of low impact (see Fig 1). Clean water, mass immunisation, better education and safer communities do more to improve population health than any other medicine. And what is more, increased investment in these high impact areas of socio-economic health enables individuals to make more healthy choices for themselves. Too much of our health investment is in low impact areas of expensive clinical services and one-to-one therapy.

Fig 1. Health Impact Pyramid (Frieden Reference Frieden2010).

Consideration of our healthcare investment (pre-COVID-19 year 2018) makes this point even more sharply. In that representative year (Pre-COVID-19) (2018), Ireland’s health spending was skewed towards the areas of least population impact. The lowest proportions of investment went to Public Health (less than 0.6 Billion Euro out of a total 17 Billion) and to Mental Health (less than 0.9 Billion out of a total of 17 Billion Euro in State Investment) (CSO, 2021). In terms of population health, we have been investing in the wrong areas (i.e. areas of low impact). The major burdens of disease in our society are socially derived. To paraphrase Michael Marmot, ‘If we want to make our patients well, we need to make our communities well and that means addressing the social determinants of illness’ (Marmot & Wilkinson, Reference Marmot and Wilkinson2005). This was true at the time of our meeting, and it remains true now after COVID-19. Socio-economically deprived groups have been disproportionately affected by the disease and also by the impacts of lockdown measures.

How can the next generation of therapeutic be enhanced?

The novel COVID-19 vaccines are a source of great hope and much excitement. New agents will emerge. Now we need to do whatever it takes to ensure that these are rendered effective in the community. Without wishing to disregard advances in other areas, there are lessons to be learned from the extraordinary era of therapeutic innovation in mental healthcare in the 20th century. In one decade between 1950 and 1960, there were more pharmacological advances than in any period before or since. It is worth considering firstly why that era of psychopharmacological advance began and secondly why it ended. Three factors contributed firstly to the emergence and subsequently to the decline of innovation in psychiatry. They were: (i) Scientific Serendipity, (ii) Overwhelming necessity, and (iii) Societal Support.

Science, necessity and public support

In Europe in the aftermath of World War, two large reserves of the explosive agent ‘Hydrazine’ lay in stock piles abandoned by the Nazi regime. These stocks provided the basis for scientific innovations leading to the development of the first anti-tuberculous antibiotics and the MAOI antidepressants. Serendipity and science came together. The benefits and limitations of Isoniazid and Iproniazid and Tranylcypromine have been well documented, but it is likely that none of these agents would have been developed had three elements not been in place; scientific serendipity, overwhelming necessity and public support. Firstly, the initial substrate became widely available for scientific study, and secondly, overwhelming levels of need were recognised within the community in terms of mental health and physical health. Tuberculosis was prevalent across the western world and the mental asylums were full to overflowing. The scale of institutional psychiatry reached a peak in Ireland in 1960 where one in every 50 citizens of the republic of Ireland was a resident in a psychiatric institution (Kelly, Reference Kelly2019). Public support was also a factor. New medical treatments for tuberculosis and mental illness were unopposed initially. This was long before the failures of institutional psychiatric practice brought psychiatry as a whole into greater disrepute. Heinous physical interventions such as unguided psychosurgery and unmodified electroconvulsive therapy eventually came to public attention. Public frustration with asylum care for mental illness was growing even before dissent in psychiatry had reached its zenith in the mid-1960s (Clare, Reference Clare1976)

So in a unique decade of psychopharmacological progress, these three factors, scientific serendipity, great necessity and public support united to facilitate most of the pharmacological treatments still in use today. These treatments included the mood stabilizer Lithium Carbonate by John Cade in 1946, the antipsychotic Chlorpromazine by Delay and Deniker in 1950, the benzodiazepine anticonvulsant chlordiazepoxide by Leo Sternbach in 1955 and the atypical antipsychotic Clozapine by the swiss pharmaceutical Wander AG in 1958 (Le Fanu, Reference Le Fanu2011).

Subsequently, progress in psychopharmacology stalled and psychological medicine descended into the era of dissent. There were other advances such as those in psychotherapy, policy development and service reorganisation but no further giant leaps. The key factor missing was public support. The circumstances necessary for development disappeared as public support diminished and mental healthcare was overshadowed by the anti-psychiatry movement.

The future of 21st century healthcare? Lessons learned from the ‘wellness movement’

Hopefully today’s critics of ‘the medical complex’ (Breggin, Reference Breggin2007) will not be as antithetical when it comes to population health, even if they remain skeptical of the motives of institutional medicine. Some continue to regard the profession as corrupt and they still ask ‘whether medicine can be cured?’ (O’Mahony Reference O’Mahony2019).

Together public health and mental health can rise to this challenge. We must not neglect mental health either in policy-making or service development during or after the pandemic. It is likely that the economic and social consequences of the pandemic will lead to even greater demand for mental health services.

Better communication with all the stakeholders in healthcare will be needed to sustain public support for vaccination and immunisation programmes and to prepare for further mass shocks to our population health and our health system.

We could start by acknowledging the failure of traditional ‘illness’ models of healthcare and continue by embracing the growing popular scientific movement for ‘wellness’, by recognising the increasing scientific consensus around our environmental hazards, our needs for better diet, exercise and self-care (Lucey, Reference Lucey2021) and the importance of the brain-gut axis (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Cryan and Dinan2019). Public health and mental health data already acknowledge the need for greater balance in our life. Public support for treatment and prevention of severe and chronic mental illnesses will not be diminished by our advocacy for the concept of ‘wellness’ more generally? Population health science is not opposed to the critics of traditional health care. As advocates for population health we could show the public that medicine can be cured and public trust can be restored.

Conclusion

Opposition to population health measures could grow just as quickly as it did to psychopharmacology and psychiatry. Although support for essential public health measures including novel vaccination is high at present, such sentiment is more fragile than we think and it could be temporary. Maintaining public support could be the most significant and enduring contribution we make to the success of 21st century population health.

The novel COVID-19 vaccines represent a major addition to our public health tool kit (Walsh et al. Reference Walsh, Frenck, Falsey, Kitchin, Absalon, Gurtman and Lockhart2020) and this is progress of which the modern ‘medical complex’ should be justly proud. To be sure, scientific serendipity and overwhelming necessity played a role in their rapid development but public support is also key. Advocates for public health and mental health and their service providers still have a great deal to learn about sustaining this initiative. To quote Abraham Lincoln ‘…public sentiment is everything. With it, nothing can fail; against it, nothing can succeed.’ Health professionals in public health and mental health have a major role in this regard. In the 21st century, we need to cooperate more fully with each other to redirect our health investment towards greater public health and mental health. This is not only an economic necessity, it is a therapeutic duty and a first step towards ensuring that public confidence in healthcare is restored and maintained in the 21st century.

Financial support

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The author asserts that ethical approval was not required for publication of this manuscript.