Introduction

After a gap of a few years, starting from the end of the 1980s, problems related to sexism in linguistic use returned to the centre of the political and social debate, given the increasingly significant presence of professional women occupying top management positions in companies and in society. Even in the academic world, albeit very timidly, we are witnessing the same phenomenon.

Data collected by ISTAT (the Italian National Statistics Institute) show that the gap between male and female employment has tended to decrease with time, thanks to the increasing level of education and educational qualifications for women.Footnote 1 Although limited in extent compared to the resources devoted to them, interventions to reduce gender disparity in the workplace have yielded results. Graduate women now enjoy greater professional opportunities – though this means that the differences between Northern and Southern Italy still persist. According to ISTAT, women tend to marry less and divorce more than in the past, as longevity increases; at work, the managerial positions held by women are growing and their presence is increasing in ‘new professions’, especially those connected with technology and medicine.

These social changes favour the reopening of a dialogue that seemed to have been waning from the 1990s – the relationship between sexism and the Italian language. Many female managers started to demand the use of feminine terms regarding the concordance of names and adjectives, so that sexism returned to the centre of public, social and political debate. This can be seen from the public declarations of Laura Boldrini, president of the chamber, in her letter sent to all the ‘male and female’ deputies of the chamber and to the general secretariat of the chamber, on 5 March 2015.

The institutions have reacted in different ways to the growing demand for a language that respects gender differences and is less androcentric: some language guides have been prepared for the use of public authorities (for example the municipalities of Turin and Florence, and the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice) and the topic has been taken up again by scholars of language. Linguists in Italy seem to take opposing sides: some distance themselves, arguing that it is the speakers who construct the language, while others try to investigate the roots of the problem and hypothesise some solutions, with the aim of challenging sexism and discrimination (Cavagnoli Reference Cavagnoli2013).

Compared to the end of the 1980s, interest in the subject in the field of language teaching seems to be greater, probably because of the consolidation of the discipline within the academic world. Many liminal sectors (educational linguistics, linguistic acquisition, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics) are interesting because they do not only focus on describing the uses of the language, but also on the possible interventions for change and the acquisition of greater awareness (Lepschy Reference Lepschy2008). The problem of sexism in the Italian language was also tackled by the Accademia della Crusca, the important Florence-based society of scholars of Italian linguistics and philology, which, starting from the Raccomandazioni of Alma Sabatini (Reference Sabatini1986) and from the research of Fusco (Reference Fusco2012) and Robustelli (Reference Robustelli2012, Reference Robustelli2017, Reference Robustelli2018), also produced a lot of awareness-raising research on the subject in response to the call for debate by some administrative institutions.

The syntagm sessismo linguistico, a calque of the English linguistic sexism, and a reflection of English-speaking – especially American and Canadian – cultures, appeared in Italy in the late 1970s with regard to gender differences in language (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet Reference Eckert and McConnell-Ginet2003). The expression refers to an offensive practice, a denigration and a lack of respect and consideration towards women in language, reflecting misogynistic and typically androcentric trends of other aspects of the culture. The relation between language and culture is not new to anthropologists and linguists; the discipline of ethnolinguistics has been studying language as a manifestation of culture for years, focusing in particular on the concept of linguistic prestige:

For us the moon is feminine, the sun is masculine by grammatical gender. If we were to personify the sun and the moon it would seem impossible for the moon not to be a woman and the sun a man, and this is also true for a child who might be unaware of classical mythology. L'automobile – the car – is female, but when advertisements want to highlight the strength and vitality of the vehicle, they show *l'automobilo as male; la tigre – the tiger – is also female, and therefore *il tigre should be avoided to indicate the male (as il pillolo – the pill – is invented to indicate the male equivalent of the female contraceptive la pillola). … These personifications can sometimes be justified by the use of archetypes, psychoanalytical symbols (it is easy to imagine that the car has feminine, uterine values, and the knife masculine, phallic, properties, etc.). However in many cases this personification is guided only by the grammatical gender (and then maybe rationalised according to the facts).Footnote 2 (Cardona Reference Cardona2006, 88).

The arbitrariness of grammatical gender was one of the first discoveries of ethnolinguistics, reached through the use of translation and comparison between languages (arbor [tree] in Latin is feminine, while albero is masculine in Italian). Beyond the descriptive dimension, it seems significant to reflect on the consequences of language and to ask ourselves to what extent a linguistic practice reflects a cultural one.

If in Italian, within the word patrimonio – heritage – there emerges the lexical allomorph patr-, a variation of padr-, and in matrimonio – wedding – we note matr-, a variation of madr-, does this mean that goods and property are a prerogative of men while the family and children are related to women? Answering the question is not so simple: if it seems clear that lexical roots do not influence cultural practices explicitly, the same cannot be said for the implicit effects, exemplified for instance in declarations by conservative Italian politicians about the traditional family consisting of the breadwinner man and the childbearing woman.

Language has an effect on the perception of the world and on cultural belonging (Vygotskij Reference Vygotskij1962), but it is difficult to establish to what extent this effect is pervasive, especially with respect to speakers’ choices (Nitti Reference Nitti2018). Lepschy (Reference Lepschy1988) was doubtful about the detection of ideological prejudice within grammatical organisation and with respect to the modification of the language planned by the institutions, because this attempt would be prescriptive, going against the spirit of Alma Sabatini's proposal (1986). However, far from being polemical, oppositional and futile, the academic debate on sexism in language developed in Italy precisely from these two contributions, which defined lines of research and paths that are still valid in contemporary study.

Sexism in everyday Italian language is not questioned here – proverbs like mogli e buoi dei paesi tuoi – literally, ‘wives and oxen of your own villages’, or ‘stick to your own kind’ – or donna al volante, pericolo costante – ‘woman behind the wheel, constant danger’ – spring to mind. This discussion is about the sharing of respectful and non-discriminatory linguistic practices, especially with regard to public administration and language teaching practices (Nitti Reference Nitti2019). The University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, honouring 30 years since the publication of Alma Sabatini's book, hosted a conference on Italian language and sexism on 30 March 2017, inviting female and male scholars in linguistics, law and sociology to present research and reflections on sexist practices. Starting from these premises, research was conducted on the sharing of non-sexist usage in the Italian language, and on the adoption of non-sexist teaching practice of the language by the teaching staff at all kinds of schools, at every level.

Research

From March to May 2019, a survey was conducted on support for the proposals described by Alma Sabatini (Reference Sabatini1986) and on language teaching practices aimed at avoiding sexism in language. The research was conceived following the 2017 conference. Questions were based on the Raccomandazioni per gli usi non sessisti della lingua by Alma Sabatini (Reference Sabatini1986), and included proposals by academic institutions and territorial and legislative bodies. Once a representative sample of teaching staff was identified, a questionnaire was submitted in five Italian cities. This included a series of questions about the level of knowledge of the recommendations on non-sexist use of language proposed by some institutions (Italian municipalities and universities, the Accademia della Crusca, the presidency of the council of ministers 1986, the presidency of the chamber of deputies 2017), and about how much these recommendations had been implemented. The questionnaire also dealt with language teaching practices (Businaro Reference Businaro2008), the correction and evaluation of errors, and linguistic style.

Schools are ideal sites for the observation of linguistic change, both in the students, who reflect the typical diastratic varieties of young people, and in the teachers, who are in charge of providing linguistic models and promoting a metalinguistic competence. This produces the ability to reflect on the language and to describe it: ‘The language informs (of itself) the thought of those who speak it because it is the instrument used to discover reality’ (Cardona Reference Cardona2006, 89).

One of the critical points of the research concerns the variability of individual language choices: it is not always easy to understand how much a single individual reflects socially shared practices and uses. Guidelines for teachers on non-sexist use (Nitti Reference Nitti2019) could only be framed after evaluating evident discrepancies in our data due to the type and level of education and the territorial context of the research (Klemens Reference Klemens2007).

The research context

We decided that a sample made up of 500 teachers from Italy was a reliable and representative source: 296 were from primary schools, 121 from lower secondary schools, and 83 from upper secondary schools. 23 per cent of the respondents were engaged in teaching Italian as a second language. The informants came from different parts of Italy – Turin, Genoa, Milan, Verona, and Venice. The sample was gathered through social media and, where possible, the mailing lists of professional training centres.

Figure 1. The distribution of respondents

The questionnaire

The research was carried out in different and sequential phases: reference to the original scientific literature; the identification of a category of respondents; the structure of the questionnaire and its distribution in paper or telematic form; and finally the analysis of the data and the drawing up of conclusions.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections: a first part containing four questions requesting professional details, to gather information on the profile of the respondents; a second part, also of four questions, on their professional institution, for the purpose of identifying possible practices to combat sexism; and a last part of 22 questions, concerning the sharing of some of Sabatini's Reference Sabatini1986 proposals for a non-sexist use of language. The last questions were structured to evaluate language teaching practices and awareness of a non-sexist use within these practices. Each question and each section included a space for free notes and comments, and out of 500 respondents, 56 contributed their opinions, making the subsequent phase of data processing even more complex. While most respondents opted for the electronic version, some teachers (8 per cent) preferred to complete the questionnaire in paper form. These were posted in an anonymous sealed envelope.

The time needed for completion ranged between 20 and 30 minutes and the title page of the questionnaire required a report on this timing, an acceptance of the law on the treatment of data and privacy, and a declaration of responsibility. It also included the name of the person responsible for the data processing and identified the venue where the publication of the research was to be presented – the second Women's Congress International Colloquium, in the ECampus University, Novedrate (Como), held from 9 to 11 May 2018.

Data analysis

The data analysis phase proved to be very detailed, due to the numerous qualitative notes included in the questionnaires. Each section, in fact, gave the responder the possibility of inserting a comment. The comments were associated with the answers and subdivided into different categories in order to be estimated statistically, despite the significant individual variability.

It should be noted that out of 300 questionnaires, only six were returned partially completed and none completely blank. It was decided to calculate the answers of the six partially completed questionnaires along with the others and to report the missing answers with the label ‘don't know / no response’. In some cases, the lack of answers was indicative of a lack of confirmation or certainty regarding a previous question: if the respondent replied that the institute where he/she worked offered interventions to combat sexist use of language, but they were not able to identify these, or did not want to answer, this was very significant for the research, since it partially nullified the previous answer or lessened its scope.

The questions

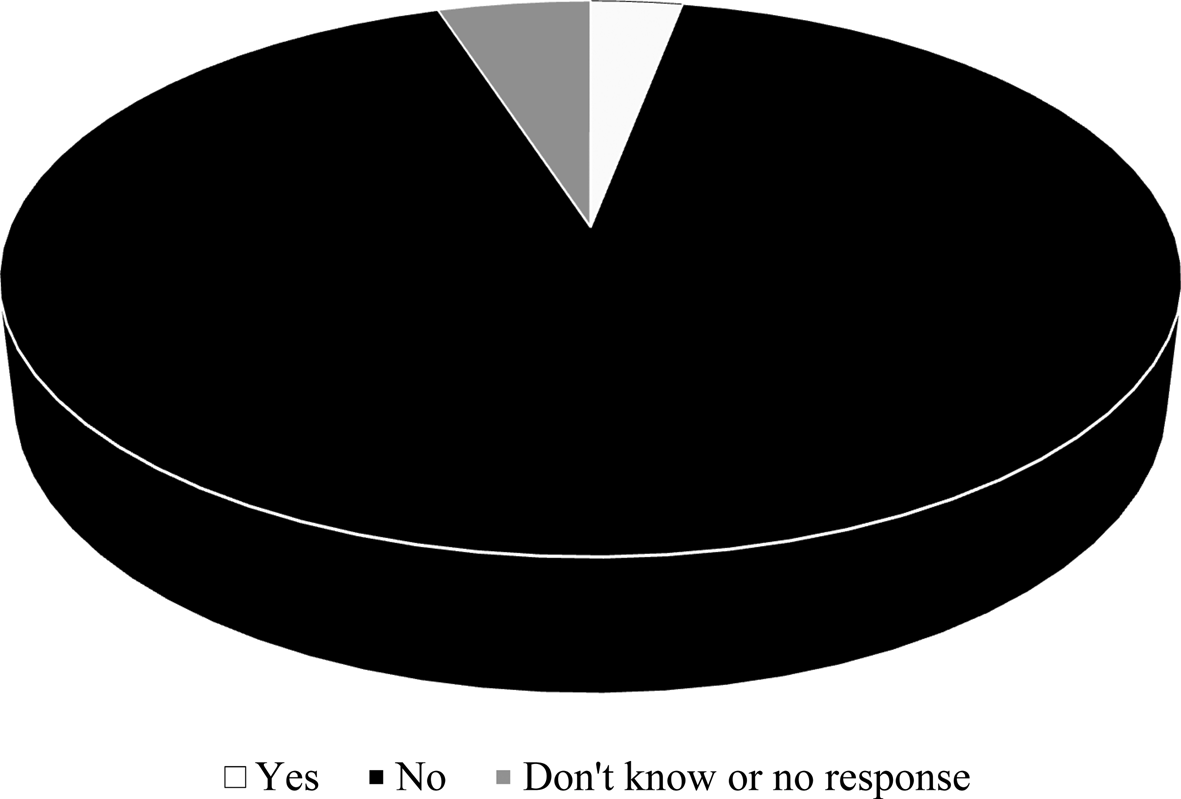

The first question asked whether, within the professional context, there existed institutional initiatives to counteract sexism in language. Less than 7 per cent of the total sample, distributed mainly in primary schools and universities, responded affirmatively while the responses from upper secondary schools were almost entirely negative. With respect to the type of proposed interventions, the majority of male and female interviewees stated that they could not accurately identify any institutional action or, simply, did not answer the question. Less than 4 per cent of the total sample reported that the interventions mainly concerned the sensitisation of the teaching staff, training with experts and the drafting of communication guidelines.

The second question concerned the awareness of existing research regarding the opposition to sexism in the Italian language: 53 per cent of the sample had no knowledge of this, fewer than 8 per cent did not answer, and the remaining responders were aware of the studies of the Accademia della Crusca (29 per cent) and declared some knowledge of the guidelines for public communication (8 per cent), while the lowest percentages knew the Recommendations of Alma Sabatini (1 per cent) and the studies of Italian and foreign academic experts (1 per cent). The Accademia della Crusca, on the basis of the notes on the questionnaire, emerged as an authority on standards and linguistic practices, similar to those elsewhere in Europe, but only on a par with other institutions and research institutes, despite its historical prestige and productivity.

With reference to linguistic use and practice, the survey contained a two-pronged question on ‘non-marked neutral male’ terms, which Alma Sabatini proposed avoiding.Our question included two sub-questions: is i diritti dell'uomo (men's rights) a sexist term? And would you replace it with i diritti umani (human rights)? The aim was to identify the perception of sexist practice and the degree of agreement with Sabatini's proposal. To both questions, the male and female respondents answered no: the syntagm was not perceived as sexist (97 per cent) and there was no intention to accept the Sabatini proposal (98 per cent).

As for the second question, to avoid giving precedence to the male in terms representing opposing couples, respondents were asked if they agreed that the phrases ‘men and women’ and ‘males and females’ should be inverted. The answers were unanimous: the priority of the male term was not recognised as being sexist (100 per cent), and less than 5 per cent were interested in accepting the proposal to invert the terms. The same answer, with very similar percentages, was given to another question on the same subject, whether to replace ‘brotherhood among states’ with ‘solidarity between states’.

Alma Sabatini (Reference Sabatini1986) identified this use of language as the ‘non-marked masculine’ syntagm, that is, the use of masculine gender and masculine meaning to refer to the whole of humanity or to a collection of men and women. In these cases, it is common practice to consider the male term as neutral, but on a linguistic level this concept is considered incorrect, since the Italian language does not have a neutral gender: the male term would therefore be an extension of the use of the masculine with an inclusive function. The expansion of the functions assigned to the male term was relevant for a good part of the history of the Italian language (D'Achille Reference D'Achille2004), and has been partly explained in grammar books. It is widespread in literature and crystallised in aphorisms and proverbs (Robustelli Reference Robustelli2017). The next question concerned the concordance of the past participle with the masculine when the subjects are predominantly female. Of our respondents, 98 per cent did not recognise this as sexist, and did not intend to adapt their usage (96 per cent). Some comments regarding the answers were particularly significant: P., a primary school teacher, stated that ‘pupils often practise the accordance based on the prevalent sex’ and T., a university teacher, admitted that ‘in such cases Italian grammar is oriented towards the plurality and not to the masculine, although this is not commonly practised’. In addition to these two statements, seven others brought the issue back to the grammatical rules, arguing that the Italian grammar that was taught in primary schools only allowed the possibility of concordance with the masculine. If we consider the main grammar reference books for the Italian language (Serianni Reference Serianni1988, Dardano and Trifone Reference Dardano and Trifone1997, Andorno Reference Andorno2003, Salvi and Vanelli Reference Salvi and Vanelli2004), we notice that this aspect of verb agreement is absent. However, according to the comments of three respondents, it seems to be explicit in the Italian language manuals for primary school and for teaching Italian as a second language. In these cases, it would be fair to make a distinction between the descriptive norm and the statistical norm, where the certified use would become a tacitly accepted norm by the speakers and theorised within the pedagogical grammars, although not in the descriptive ones (Nitti Reference Nitti2017). It follows that it is a statistical norm, rather than a rule – a regular use, a procedural tendency, to which the speakers adhere (De Benedetti Reference De Benedetti2009). On the descriptive level of a language, a grammar book cannot always explain a use:

[I]n particular, certain grammar books of scholastic tradition are often inconsistent and unreliable … one cannot reduce everything to the right / wrong dichotomy but there are many intermediate shades of acceptability, … some rules handed down from generation to generation do not even exist. (De Benedetti Reference De Benedetti2009, 6).

The question of the concordance between past participle and several predominantly female subjects does not feature in the traditional descriptive grammars and the procedure would seem similar to the noun-adjective concordance: according to Serianni (Reference Serianni1988), if the nouns are of different genders, the adjective assumes the plural number and is preferably expressed with the masculine, but Robustelli (Reference Robustelli2017, 17) suggests that in this, as in other cases, ‘we are facing wide margins of change’.

The other questions in our survey mainly concerned the avoidance of the asymmetrical relationship between women and men in the political, social and cultural fields: Alma Sabatini (Reference Sabatini1986) proposed different approaches on a language level, mostly concerning the professional sphere. According to her, a dissymmetry represents a disparity in the use of language, when referring to men and women, both of a semantic nature – concerning the meaning of the terms and forms adopted – and a grammatical one, that is, related to the possibilities of linguistic structures. Semantic dissymmetry would, however, be connected with the connotative and denotative meaning of words and their collocations: the woman is identified as weak, fragile, angelic, hysterical. We often fall back on nicknames and diminutives, and there is no lack of cases of enantiosemy with respect to gender: un governante – a governor – and una governante – a housekeeper (Robustelli Reference Robustelli2017, 28). As for the use of the feminine definite article before feminine surnames related to institutional positions or the mere presence of women in the professional world, such as La Pivetti, La Boldrini, La Meloni, La Camusso, La Montalcini, almost all the respondents recognised a sexist use (78 per cent), but the number of those who would be willing to adopt a different communicative style, renouncing the definite feminine article, is significantly low (17 per cent). It is significant how the use of the definite article, in these situations, specifically underlines the gender: we need only note the use of La Anselmi, the Italian politician and minister of 1976: albeit before a name that begins with a vowel, elision is not practised, emphasising the gender within the article. The question is not new in descriptive linguistics: ‘with the female surnames the traditional norm, which it might be good to continue to follow, requires the obligation to use the article …. However, it should be noted that the current trend is towards the use of the simple surname without the article, as for the masculine’ (Serianni Reference Serianni1988, 146). Beyond the normative-prescriptive judgments, Serianni (Reference Serianni1988, 146) noted that ‘the current journalistic use favours the suppression of the article for the sake of rapidity’. In the late 1970s, the question of the definite article before female surnames was already perceived as a sexist use ‘for the minor importance attributed to the sex of a person with respect to their professional or political activity’ (Lepschy and Lepschy Reference Lepschy and Lepschy1981, 152). The use of the definite article with male surnames would indicate its glory and prestige and would not have a sexist but an encomiastic-celebrative function, as we see in the example il Botticelli, indicating a strong temporal discontinuity with respect to the life of the person or an alleged objectivity of the narration or description (Serianni Reference Serianni1988, 147). It is likely that the resistance of speakers to the abolition of the definite article in front of feminine names, highlighted by the sample of our informants, is attributable to the grammatical regularities learnt at school, although a metalinguistic reflection leads them to consider the practice as being sexist and discriminating.

In some cases, in addition to the presence of the article, a part of the surname, perceived as a grammatical suffix, is altered in a disparaging way, as with la Boldrina, for Boldrini; the use of the final ‘a’ in the written, or the central vowel ‘a’ in the spoken language is intentionally sexist. Aside from a purely discriminatory use, the ‘a’ would demonstrate the futility of the debate on language and sexism, so that in some circumstances some have gone so far as to signal its presence by resorting, in a derogatory manner, to a capital letter, as in la BoldrinA, la sindacA, la ministrA. According to our sample, the situation would be different – and even more marked in terms of sexism – if the apposition signora – lady – is inserted before the surname, in an institutional list of women and men, for example la Signora Boldrini and il Presidente Grasso, for both presidents. The use of signora, often written with a capital ‘S’ and used to define a status, is considered sexist, highlighting a willingness to accept the proposal of Alma Sabatini as regards the expression of the function and not of the generic appellative (96 per cent of the sample). Regarding the use of ministra – female minister – and sindaca – female mayor – in reference to women who hold institutional positions, the sample is very divided: ministra is accepted by 43 per cent of male and female respondents, sindaca by 46 per cent. The uses of the masculine, in these cases, are perceived as sexist by 72 per cent of the sample and there is a polarisation of the perception of sexism and of the will to adhere to the feminine in cities governed by female mayors such as Turin and Rome, or those which in the past have enjoyed the presence of female mayors, such as Naples.

The Accademia della Crusca has, in fact, repeatedly defended the use and the accuracy of feminine forms of these professional names, as being grammatically acceptable; the problems are more evident when admitting new feminine terms such as difensora, ingegnera and recognising a form as prevalent where there is uncertainty, as in the case of avvocata and avvocatessa or professora and professoressa, studente and studentessa. Another fracture line in the sample concerns the age of those who responded: up to the age of 45 there is a fairly rooted attitude towards the perception of sexism in the language and a support for change. After the age of 45 the tendency is inverted and resistance increases with advancing age. It is significant to note, on the other hand, that there are no particular inclinations connected with gender: women and men responded fairly uniformly, their responses varying chiefly with age. That the youngest age groups are the ones most open to change is well known (Berruto Reference Berruto2004), although the linguistic changes proposed by young people – and by advertising – rarely last in the language.

The last questions were aimed at identifying a relationship between the opposition to sexism and the teaching of the Italian language, in particular regarding the presence of language teaching interventions to encourage reflection on the language, on sexism and on practices of correction and evaluation of sexist uses by students. The respondents opted mainly not to include in their own curricula reflection on sexist use in language, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Reflection on sexist practices in the language, within respondents’ own language teaching activities

The question of language and sexism seems to remain outside classrooms of all grades, although it should be pointed out that in universities the intervention rate is significantly higher than in other educational contexts (+26 per cent). The dispute is seen as purely social and academic and does not interest those in the language teaching profession.

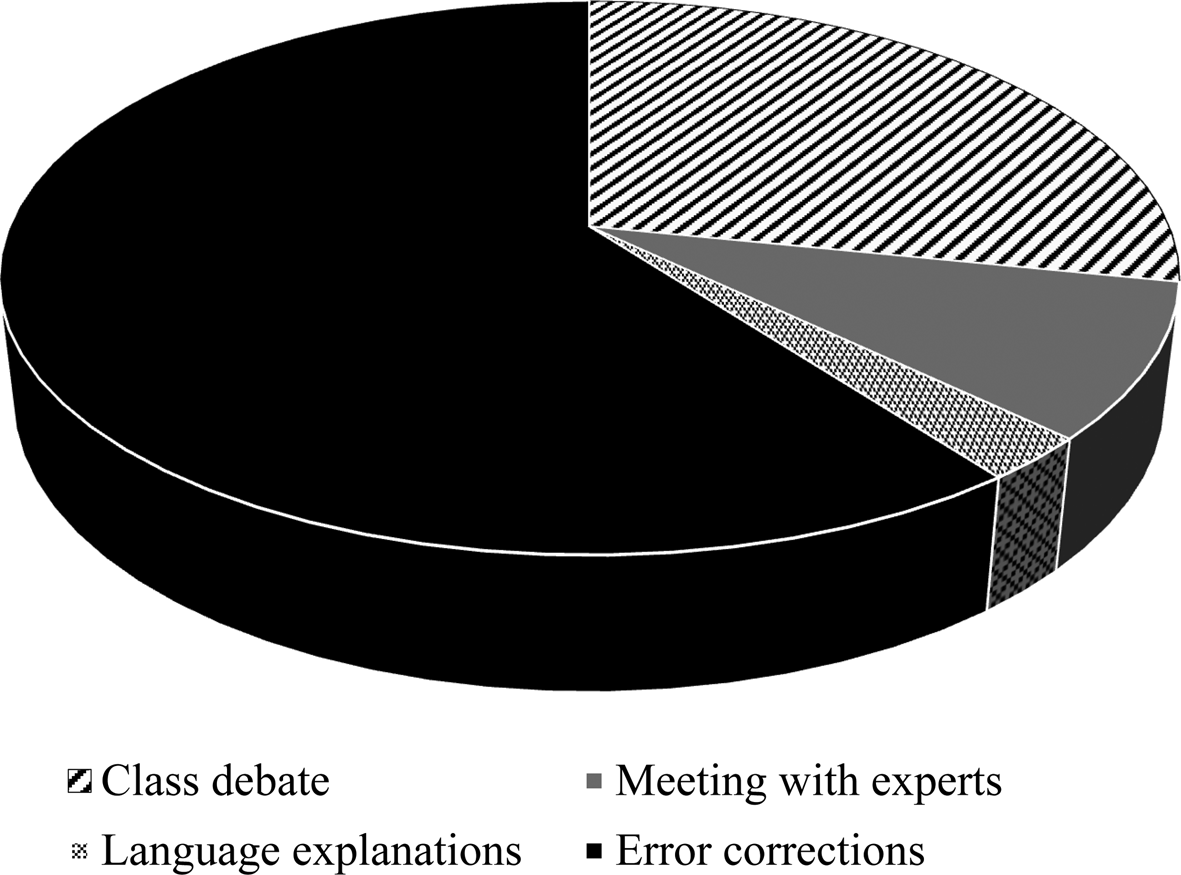

A few comments relating to the question are worthy of note: eight respondents claimed that they did not have enough time to deal with the issue and 23 individuals declared that they had to adhere to the ministerial curricula, and were therefore unable to deal with more interesting topics. These comments point to three significant issues: first, there is a resistance to change, which is characteristic of Italian schools; second, a prescriptive-normative vision of ministerial curricula prevails; third, the overall effect is a loss of teaching autonomy. The desire to begin a reflection on sexism would seem to be obscured by contingencies. In any case, it is advisable, for research purposes, to investigate the practices and record the valuable contribution of those who spent their time on the questionnaire. Figure 3 shows the main ways that language teaching practice fosters reflection on sexist elements in the language.

Figure 3. Ways of intervening to promote reflection on sexism in language, within the current teaching practice of the Italian language

The correction of errors seems to be one of the chief ways to address the question of sexism in language and it is appropriate to quote the comment of a respondent, S., who declared that only through correction, ‘the red line, will his/her lower secondary school students understand that women have the same dignity’. For the student, perceiving forms of discrimination and writing a text correctly are treated by their teacher in the same way. In relation to awareness of discrimination, there is no didactic treatment: the teacher corrects the mistake without explaining why. Furthermore no training opportunities exist, nor do meetings with available experts, such as historians of the language and linguists who deal with the Italian language and its teaching.

Most respondents reported a preference for teacher-led explanation in class, compared to group discussion between students. This is probably the result of a scholastic tradition that perceives grammar and language as being learnt in a passive way, according to the Italian tradition, while language-educational research is fairly uniform in retaining the teaching of language as a co-construction of knowledge (Lo Duca Reference Lo Duca2013).

Conclusion

The analysis of the data has helped to reach some conclusions on the sexist dimension in the language with regard to the teaching staff engaged in Italian language courses. According to the sample, the attention given by educational institutions to practices aimed at combating sexism is scarce and, if we consider sexism in language, practically non-existent. The awareness of interventions on sexism in language is not low, although it is limited to the studies conducted by the Accademia della Crusca. A European perspective, and attention to other languages, especially those typologically and geographically close to Italian, are lacking.

In 2015, French MP Julien Aubert was forced to give up a quarter of his parliamentary allowance for a month, as a sanction for repeatedly addressing the current president with the expression Madame le Président. The anecdote is indicative of the vitality of the debate regarding the relationship between language and sexism in very similar contexts to the Italian one. In Italy, attention to guidelines and indications by public administrations is scarce and is seen as a superfluous and sometimes annoying, because it is far removed from traditional conventions. Teaching staff recognise sexism in the language in some forms, especially those particularly evident on a morphological level, rather than on a syntactic one, but they are reluctant to change, probably due to the stubborn prevalence of conventional forms.

On a language-educational level, the most frequent strategy for dealing with the question of sexism in language concerns the correction of errors, while interventions for reflecting on the language and interactive participation regarding the problem are partially or completely absent. Contrary to what might well be assumed, there are no discrepancies with respect to the sex of the sample: women and men responded in a similar manner. A differentiation only emerged between diverse age groups. The youngest respondents declared themselves more open to proposals for change and demonstrated greater sensitivity and awareness with respect to the identification of sexist practices.

The most evident difficulty for the respondents concerned the sexism hidden behind supposed grammatical rules, especially regarding the logic of the text and the syntax. Overall, a static consideration of grammar emerges, exclusively of a normative-prescriptive nature, while the value assigned to the investigation of language as a dynamic and complex phenomenon appears to be small. There were no particular differences regarding the location in which the survey was carried out: the respondents contacted in different cities reacted similarly, except for the issue of avoiding dissymmetric forms for ministra and sindaca, where support for change and the consideration of common use as being sexist occurred in cities with current or past female mayors.

The reflection on the feminine for professional names ‘has dragged on for years and is still fluctuating, raising doubts and questions in an increasingly wider audience, because it reflects social changes still in progress’ (Robustelli Reference Robustelli2017, 10). If we consider less prestigious professional names, the average speaker would have no problem with the feminine version, and no one would object to forms like maestra – primary school teacher, infermiera – nurse, panettiera – baker, and pasticciera – pastry chef. The same questions in our survey are currently the subject of debate in the media, mostly newspapers and newscasts, but also beginning in the publishing industry.

The scholastic publishing industry, in particular, through the POLITe self-regulation code (Pari Opportunità e libri di testo – Equal Opportunities and Textbooks) and art. 1 of Law 107 of 07/13/2015 (La buona scuola – the good school) has seen a flourishing of proposals for combating sexism, although many textbooks, especially for primary schools, continue to use materials from other periods of Italian culture, which use sexist language. The trend of those who answered the questions in our survey, analysed via their comments and notes, is strongly polarised: few individuals, even those with little linguistic knowledge, believe that sexism in the language represents a problem and feel the need to tackle it; other respondents consider the debate sterile and inconclusive, believing that other matters are more urgent. One of the worrying, but noteworthy, issues that emerged from the comments concerns the alleged linguistic impoverishment of young people. According to the respondents, young people were replacing the high forms of the Italian language with shoddy, ungrammatical and inappropriate expressions. In reality, sociolinguistic studies confirm that the language of young people is far from being poor and is actually a fecund territory for the creativity of language (Berruto 2006).

In conclusion, regarding the relationship between language and sexism, it is not possible to envisage imposing a rigid rule that is ‘devoid of alternatives and oscillations’ (Robustelli Reference Robustelli2017, 18). The proposals of Alma Sabatini have provoked the beginning of a series of questions, of reprimands, of uncertainties and reactions – sometimes excessive on all fronts – that have remained valid in society over time. If on the one hand schools in Italy are somewhat insensitive to the relationship between the language and the construction of a personal identity, including a gender identity (especially in the light of European moves towards abolishing all forms of stereotypes), on the other hand we should still invest in the synergy between academic studies, staff training and language teaching practices.

Contrary to common opinion, the Italian language does not oblige speakers to resort to certain forms and sexism is not per se inherent in the language (Fresu Reference Fresu2008). Italian offers different possibilities and allows gender differences to be expressed with full respect, allowing the use of masculine, feminine and mixed forms, avoiding stereotypes (Fusco Reference Fusco2012).

We often read in social networks and hear many statements from public figures regarding the absurdity of the reflection on sexism in the language, on the fact that many grammatical suffixes end in -a, as in dentista – dentist, and so would have to be accorded an -o ending for a singular masculine. The problem in these cases arises from a lack of knowledge of the Italian language and its history, which reveals that the grammatical and lexical morphemes are of different origin. Speakers of a language are, to a large extent, unaware of linguistic choices and it would therefore be necessary for schools to work more on metalanguage, on the ability to actively reflect on the language, in order to build, analyse and understand its properties and nuances. Grammar, in this sense, is the most important perspective for the study of language and its uses, and not a set of rules to be strictly observed (Lo Duca Reference Lo Duca2013). Linguistic dictates, especially if they originate from the top of the institutions, are not conducive to effective use of the language, and the same can be said for all the handbooks being compiled by public administrations. Our language belongs to everyone and must be built by everyone, because it represents a common good.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the co-editor of the journal, Penelope Morris, for her comments and suggestions. I am also very grateful to Fabiana Fusco and Giulio Facchetti for their unfailing support during the investigation.

Note on contributor

Paolo Nitti holds a PhD in Law and Humanities from the University of Insubria, and he is adjunct professor of Cognitive Linguistics at the same university. He is director of the journal Lingua e Testi di Oggi and vice-director of Scuola e Didattica. He has also taught at the University of Padua and the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. He is the academic coordinator of the Master's degree Nuova Didattica delle Lingue (University eCampus). His publications include La grammatica nell'insegnamento dell'italiano per stranieri (Saarbrücken: Edizione Accademiche Italiane, 2017); Didattica dell'italiano per gruppi disomogenei and Didattica dell'italiano L2. Dall'alfabetizzazione allo sviluppo della competenza testuale (both Brescia: Editrice La Scuola, 2019).