Introduction

The use of mobile phones in the workplace by medical professionals has become increasingly common. Although it can be difficult to distinguish between personal and professional use of mobile devices in the workplace, quick access to good quality information is undoubtedly an aid to clinical care. With the development of not only smartphones but also adjunct technology, the scope of smartphone applications has expanded beyond them being purely reference platforms. There are a growing number of applications designed to be used directly in patient assessment, including applications to convert smartphones into otoscopes, endoscope viewers and numerous hearing test applications.

Nevertheless, with the increasing number of applications, it can also be difficult to establish which products provide accurate, secure and up-to-date information. Users cannot rely on the limited information supplied on the mobile phone platforms from which the applications are downloaded; further research is always required to establish the application's evidence base, which may be time consuming and limited by a lack of readily available information.Reference Aungst, Clauson, Misra, Lewis and Husain1 Additionally, given the basic search functions of the application stores themselves (no function to filter applications intended for professional use and limited results for technical terms) even identifying potentially useful applications can be an arduous process.

The purpose of this article is to establish the number and type of ENT-specific applications currently available. In addition, a small selection of applications have been reviewed, in order to highlight some of the innovative ways in which smartphone applications can be used in clinical practice and to analyse the ease with which their validity and evidence base can be assessed.

Materials and methods

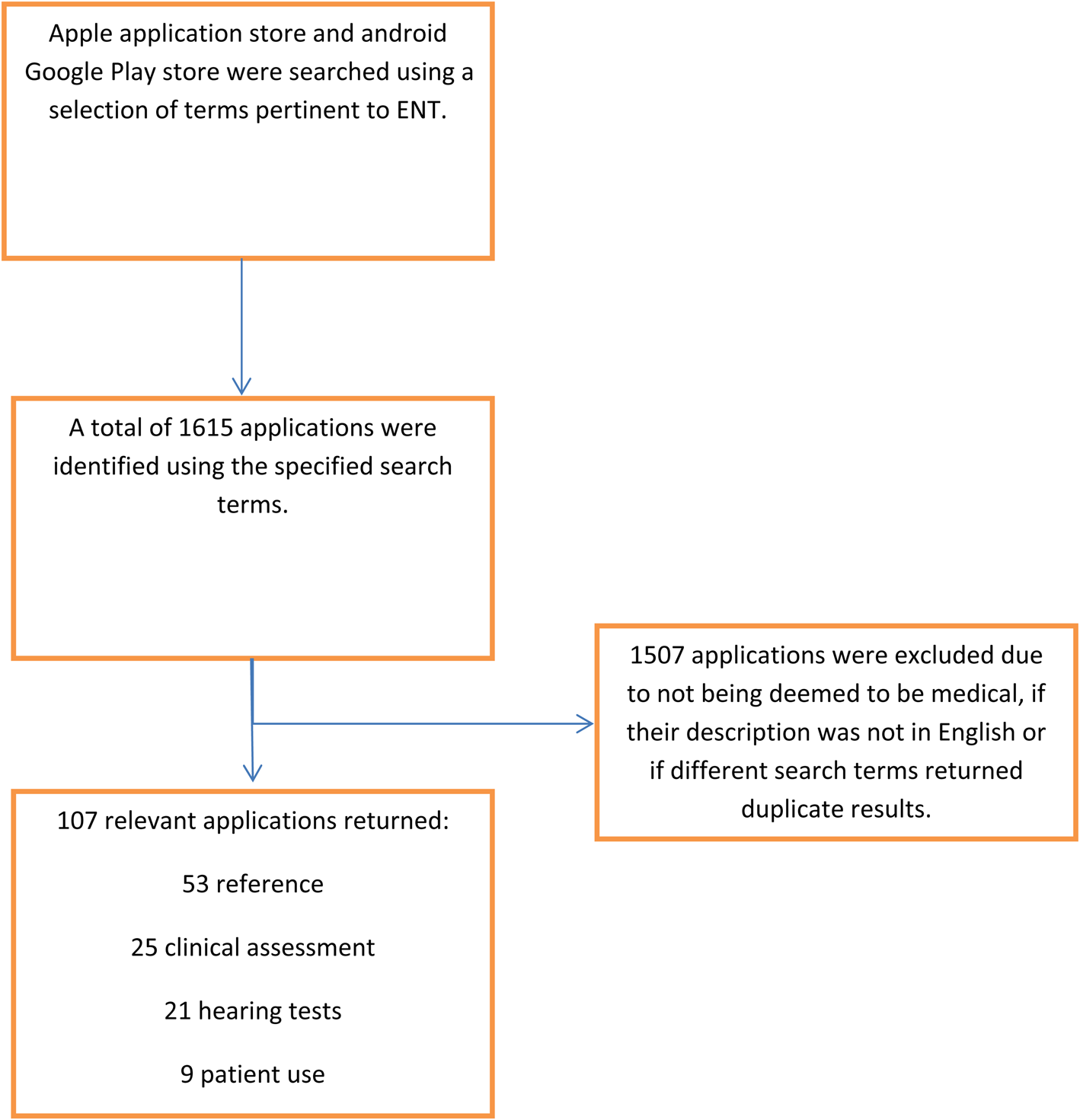

The application stores of the two most popular mobile phone platforms, Apple® (iOS App Store) and Google® (Google Play), were searched for ENT-specific mobile applications. Search terms used included: ‘ENT’, ‘otolaryngology’, ‘otology’, ‘rhinology’, ‘laryngology’, ‘head and neck’, ‘hearing’ and ‘otoscope’. The descriptions were reviewed to ensure the applications were appropriate and relevant to the specialty. Applications were excluded if the description was not written in English or if the applications were not intended for clinical use (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. A flow diagram of the search method used.

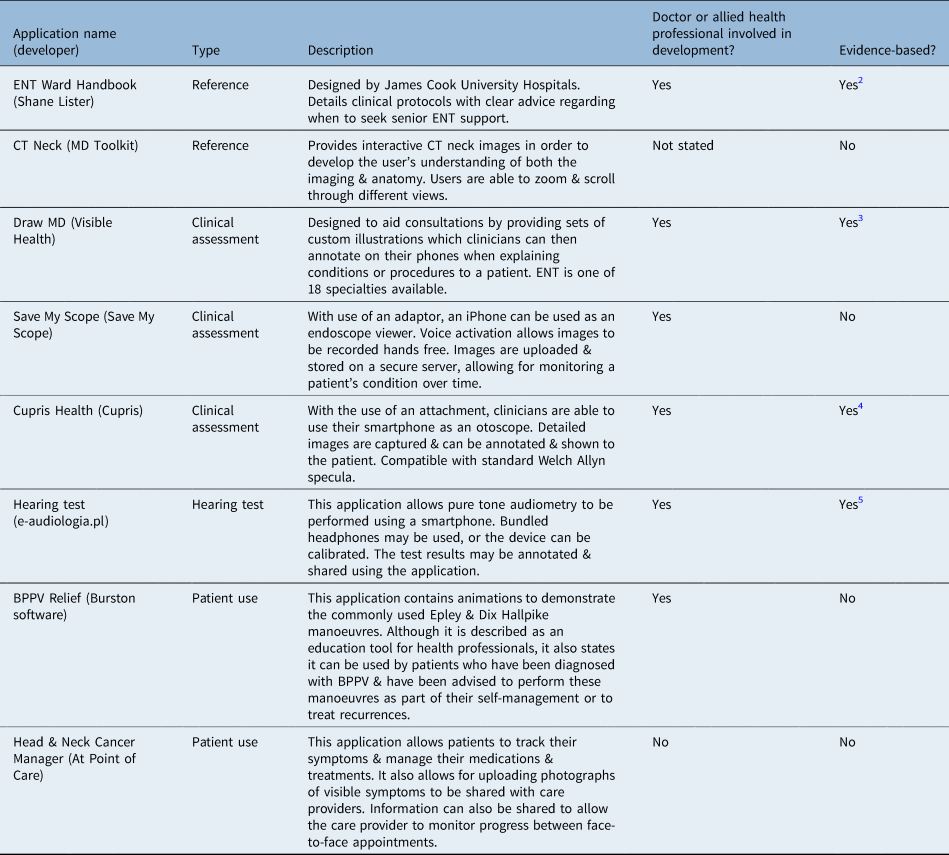

Eight applications returned from the search were then selected for more detailed review; these were chosen to represent the different categories of ENT-specific applications available, such as reference, clinical assessment and those aimed at the patients themselves. Each of the applications had over 100 downloads on the Google Play store or a rating of over 4+ on the Apple iOS store. Application quality was assessed by ascertaining whether a doctor or allied health professional was involved in their development (both application description and developer website were reviewed) and whether there was a readily accessible evidence base for the application (research publications available either via a PubMed search or the developer website).

Results

The search was undertaken in July 2019. A total of 107 ENT-specific applications were identified and categorised according to their intended use (Table 1). Of the applications identified, 48 per cent (n = 53) were reference applications. These applications included textbooks, study aids and question banks aimed at both medical students and ENT trainees. The remaining applications were predominantly intended for clinical assessment (n = 25). There were a notably large number of hearing test applications available (19 per cent, n = 21). Aside from hearing tests, other applications intended for use during assessment included otoscope applications, endoscope viewers and screening tools. The smallest category consisted of applications intended for patient use (n = 9), which included symptom trackers and self-management applications.

Table 1. ENT-specific applications identified on the Apple App Store and GooglePlay

Table 2 contains a more detailed analysis of eight applications. Six of these eight applications had either a named doctor or allied health professional associated with their development. Of these applications, four also had readily accessible published research relating to the application (ENT Ward Handbook,Reference Tailor, Blackmore and Lester2 Draw MD,Reference Ji, Zhang, Fan, Han, Yang and Tang3 Cupris HealthReference Mandavia, Lapa, Smith and Bhutta4 and e.audiologia Hearing TestReference Masalski, Kipiński, Grysiński and Kręcicki5). The two remaining applications had no clear evidence base, and it was not stated whether the developers were medically trained or allied health professionals.

Table 2. Detailed review of eight applications

CT = computed tomography; BPPV = benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Discussion

This study highlights a wide range of ENT-specific applications that are available. A number of studies on smartphone usage amongst medical trainees have been published,Reference Dimond, Bullock, Lovatt and Stacey6–Reference Hardyman, Bullock, Brown, Carter-Ingram and Stacey8 in addition to specialty specific (maxillo-facial,Reference Carey, Payne, Ahmed and Goodson9 urologyReference Nason, Burke, Aslam, Kelly, Akram and Giri10 and plastic surgeryReference Reusche, Buchanan, Kozlow and Vercler11) reviews. In comparison with a study conducted in the USA in 2015 that detailed the availability of ENT-specific mobile applications,Reference Wong and Fung12 our study suggests both an increasing number and diversity of ENT-specific applications. As pre-empted in the review by Wong and Fung,Reference Wong and Fung12 evolving technology has resulted in an increasing number of applications allowing smartphones to be directly used in clinical assessment.

The ability to use smartphones as a tool for clinical assessment has huge potential for telemedicine, as discussed in a study by Swanepoel and Clark.Reference Swanepoel and Clark13 The ability to accurately measure hearing with minimal equipment, using applications such as the e.audiologia Hearing Test, provides the opportunity to deliver hearing healthcare to communities where previously it would have been unfeasible. Additionally, the ability to capture otoscope views with a smartphone and to share them remotely facilitates improved ENT care for those in isolated communities. Studies have shown the benefits of using telemedicine to aid triage in the community, providing an effective way to manage referral to tertiary ENT care.Reference Gupta, Chawla, Gupta, Dhawan and Janaki14 Smartphone applications that convert the phone into an otoscope are beneficial to such community triage schemes; the Cupris otoscope was shown to be a low-cost tool to screen for ear disease in remote locations in low- and middle-income countries.Reference Mandavia, Lapa, Smith and Bhutta4

Remote image sharing would also be advantageous in a National Health Service setting. The secure sharing of images via smartphones is particularly pertinent to ENT departments, where the senior on call is often not resident. The ability to share otoscopy images would facilitate juniors seeking senior advice, and the option to store images would allow clinicians to monitor a patient's progress chronologically without having to rely on documentation or memory.

The quality of advice that can be given remotely clearly depends on the quality of the images, and this is something that can be expected to improve as the applications become more widely used and smartphone technology progresses. Although small scale, one study has shown that an accurate diagnosis can be obtained from still images taken using a mobile phone otoscope. However, some conditions, such as middle-ear effusion, proved more difficult to visualise and correctly diagnose.Reference Moberly, Zhang, Yu, Gurcan, Senaras and Teknos15 When comparing smartphone otoscopes to traditional otoscopes, clinicians preferred the phone attachment. There are clinical implications when switching to a smartphone otoscope after examining with a standard otoscope because clinicians often changed their diagnosis.Reference Richards, Gaylor and Pilgrim16 Patient feedback was positive during a study comparing traditional microscopy to the new phone-based otoscope; patients appreciated the opportunity to visualise the pathology and felt it gave them a better understanding of their condition. When clinicians diagnosed from the smartphone images, the positive predictive value was 97 per cent.Reference Moshtaghi, Sahyouni, Haidar, Huang, Moshtaghi and Ghavami17

Although the use of smartphones during consultations can be expected to vary according to individual preference, the studies investigating the use of smartphone otoscopy noted a predominantly positive response from patients. There are a number of applications available to facilitate the doctor-patient encounter, such as Draw MD, which allows the smartphone to be used to provide patients with visual information during a consultation. A study has shown that 40–80 per cent of information conveyed in a consultation is immediately forgotten, and of the information that is retained, up to 50 per cent is remembered incorrectly.Reference Kessels18 The use of illustrations when explaining to a patient has long been promoted and acknowledged to improve patient compliance.Reference Delp and Jones19 When illustrations are used in combination with oral communication, their effectiveness is further increased.Reference Katz, Kripalani and Weiss20 Draw MD offers a modern and accessible way to provide the visual information patients require in order for them to understand and retain information accurately.

Hearing tests represent a significant proportion of the available applications, although one study has noted that very few have been validated in peer review studies.Reference Bright and Pallawela21 Other examples of applications available for use in clinical assessment include an application to objectively measure the Unterberger and Romberg test,Reference Whittaker, Mathew, Kanani and Kanegaonkar22,Reference Yvon, Najuko-Mafemera and Kanegaonkar23 and there has also been a preliminary study completed on a smartphone application to measure bone conduction thresholds.Reference Dewyer, Jiradejvong, Lee, Kemmer, Henderson Sabes and Limb24 Smartphone otoscope technology has become more established, and there are numerous studies comparing their use to traditional otoscopy as previously discussed. The use of smartphones during nasal endoscopy, using applications such as Save My Scope, represents a relatively new area of development. As such, fewer research papers exist, but initial research has shown encouraging results.Reference Quimby, Kohlert, Caulley and Bromwich25 The number of novel applications for use at the bedside will inevitably grow as technology progresses.

Data protection is an important consideration when using smartphone applications, and concerns regarding security could be a major deterrent for their usage. This is particularly relevant if the applications are used on personal devices or used to communicate patient-identifiable data or images. A lack of a regulatory framework for healthcare applications can leave the degree of security to the discretion of individual developers. One article assessing the usage of mobile phone applications in the management of bipolar disorder recommended that users exercise caution when using the applications becasuse most lacked privacy policies.Reference Nicholas, Larsen, Proudfoot and Christensen26 Another article noted that even if the application did have a privacy policy they may be difficult to access and not specific to the application itself.Reference Sunyaev, Dehling, Taylor and Mandl27 Nevertheless, there are an increasing number of recommendations regarding security and data protection measures for the applications,Reference Morera, de la Torre Díez, Garcia-Zapirain, López-Coronado and Arambarri28 including tools developed to help application designers improve the security of their software.Reference Parker, Karliychuk, Gillies, Mintzes, Raven and Grundy29 Although it remains the clinician's responsibility to be confident that the applications they use are secure, it can be expected that the security requirements will become more stringent as this field continues to grow.

In addition to security concerns, it also remains difficult to assess the quality of available applications. This review is limited in the same way as users trying to search for applications for clinical use. The mobile application stores’ search functions are limited and do not allow for the use of filters. Searches return a large number of results without the ability to identify the applications intended for professional use. Specialist search terms return very few results, while more generic terms return large numbers of applications, which users have to sift through to find those that may be clinically relevant. Without downloading the application, which in some cases requires payment, this judgement can only be made on very limited information provided in the description of the application, and the quality and security of the application can be hard to determine.

As a consequence, further research is required to ascertain the quality of an application; it is often possible to establish the qualifications of the developers via the application's description or the developer's website. Of the eight applications reviewed, over half had a doctor or allied health professional involved in their development. The majority also had published research relating to the application; however, this was often a single article, in some instances authored by the application's developer. Finding an objective evidence base for smartphone applications is arduous, and the information is often lacking. Although the number of applications is growing, establishing their security and validity still represents a significant challenge.

Conclusion

There are numerous medical applications available, and ENT-specific applications represent a very small proportion of these. However, the applications reviewed highlight the diverse range of clinical uses for these. It is clear that there is a role for mobile phone applications within clinical practice, and it would be beneficial to ascertain exactly how this technology is currently being used within the specialty. Improved privacy policies and greater guidance on application quality would enable clinicians to integrate these applications into their clinical practice with more confidence. Mobile technology will continue to evolve at a rapid pace, and consequently so will the scope and usage of smartphone applications.

Competing interests

None declared