Introduction

Ancient Egyptian is an autonomous branch of the Afroasiatic language family.Footnote 1 The Egyptian language shares a common origin with cognate Afroasiatic languages in Proto-Afroasiatic. Yet certain aspects of Egyptian vocabulary, phonology, and morphology differ from those of the other Afroasiatic languages (Semitic, Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, and Omotic). The exact position of Egyptian within the Afroasiatic language family is still being determined – Egyptian shares a number of characteristics with Chadic in particular.Footnote 2

The time period considered in this chapter (750–100 BCE) was a tumultuous time in Ancient Egyptian history. During this period, Egypt maintained trade relations and diplomatic contacts with foreign powers, and was also involved in inter-regional military conflicts. The country was incorporated into the Persian Empire by Cambyses. This first Persian period was followed by a brief rule of indigenous dynasties and a second Persian conquest before Alexander the Great invaded, and Egypt passed into the hands of the Ptolemaic dynasty after his death. This resulted in a higher number of free and unfree Egyptians living abroad than in earlier periods of Egyptian history.

Aside from significant political upheaval, this period also featured new developments in Egyptian writing. All forms of the Egyptian script reflect one underlying language – Ancient Egyptian – although the relationship that each form bears to the spoken language differs (see the section on ‘Spelling and Normalisation’). While hieroglyphs on temple or tomb walls are the iconic representations of Ancient Egyptian writing in modern popular culture, in reality information about mundane and practical elements of Egyptian life was usually recorded on papyrus documents or ostraca (limestone flakes or pottery sherds). In earlier periods of Egyptian history forms of the ‘hieratic’ script were used for cursive writing. But from the end of the 26th dynasty (664–526 BCE) onwards a script called ‘Demotic’ became the dominant cursive script, used particularly in (private) legal and administrative documentation. Demotic was eventually replaced by a script called ‘Coptic’, which became dominant from the third century CE onwards. Coptic uses the Greek alphabet, with a number of additional letters that reflect Egyptian phonemes not found in Greek. It is the only form of the Egyptian script that consistently shows vowels.

Egyptian Names in Babylonian Sources

Text Corpora

Egyptians living in Babylonia, and by extension the names they bore, are the subject of a number of dedicated studies (see ‘Further Reading’ section). Egyptian names occur in different contexts in cuneiform sources from Babylonia, often in those with multiple actors bearing Egyptian or other non-Babylonian names. Most sources in which Egyptian names appear come from urban environments.

The total number of Egyptian names that is attested is not indicative of the total number of Egyptians in Babylonia at any given time, as Egyptians and their descendants could bear non-Egyptian names. Thus, a chamberlain from Babylon, who is referred to as ‘the Egyptian’, Bagazuštu son of Marḫarpu,Footnote 3 bore an Iranian name but an Egyptian patronym. In the case of Egyptian slaves, their master might choose to change their name. As acculturation to Babylonian society took place, descendants of Egyptians took on Babylonian names, although Egyptian names could re-appear down the family line (see section on ‘Social and Historical Context’).

Text corpora and types of sources that feature persons with Egyptian names are the following:

The Murašû archive. The more than 800 texts and fragments from the archive of the Murašû business firm, dated to the second half of the fifth century BCE and located in Nippur, feature various people with non-Babylonian names, including Egyptians.Footnote 4

Ration lists for oblates belonging to the Ebabbar temple in Sippar. Several tablets from the Ebabbar temple, dated predominantly to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, feature lists of rations of barley, flour, and garments that are given to a group of Egyptian oblates (širku), many of whom bear Egyptian names.Footnote 5 The overseers of these men reoccur in several texts. No female names are recorded in these lists. The quantity of the rations the men received seems to indicate that they did not perform highly skilled labour.Footnote 6

Transactions and alliances taking place in a predominantly non-Babylonian environment. In some documents, most or all of the actors involved seem to be of foreign extraction. Notable is the marriage document Dar. 301 from Babylon,Footnote 7 wherein both the acting parties and many of the witnesses bear Egyptian and other non-Babylonian names. In the apprenticeship contract BM 40743 a man is apprenticed to an Egyptian slave for six years, and the majority of the actors in the contract, as well as the witnesses, bear Egyptian names.Footnote 8 A slave sale from Nippur (belonging to the Murašû archive) takes place between Egyptian (descendants), as both the seller and the previous owner have Egyptian patronyms, and a slave woman and her brother bear Egyptian names.Footnote 9 CT 4 34d documents a loan of dates between men bearing Egyptian names and patronyms.Footnote 10

Singular texts that mention people bearing Egyptian names in various capacities. Sometimes people with Egyptian names pop up in texts with otherwise very little context. Thus, we find a Ḫar-maṣu who was a judge in charge of a prison (ROMCT 2 37:24), but we know little else about him. Some of these texts are linked to archives.Footnote 11

Social and Historical Context

People bearing Egyptian names appear in different strata of Babylonian society.Footnote 12 Among the free population, they seem to include people ranging from a modest to an average socio-economic status. People with Egyptian names who function as high-ranking officials, or who belong to the highest socio-economic spheres, are much rarer. Some Egyptians seem to have entered Babylonia as prisoners of war. There may have been two waves of incoming Egyptians from military confrontations: the first during the reign of Nabopolassar and early in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, and the second in the later reign of Cambyses and onwards, as these were times of Egypto-Babylonian/Persian clashes.Footnote 13 The former was the origin of the male temple slaves appearing in the Ebabbar ration lists. However, Egyptians also served as free soldiers in the Persian army and may have relocated themselves and their families this way. The presence of Egyptian merchants who settled abroad permanently should also not be excluded.

Slaves with Egyptian names also appear in private contracts. The Nippur slave sale mentioned earlier notably shows some social stratification, as both the contracting parties and some of the slaves sold bear Egyptian names or patronyms. Other private documents show free persons with Egyptian names acting as contracting parties (as buyers, sellers, and tenants) or witnesses. It is not always clear if these people were acting fully independently or if they were representatives or agents of another person or institution.Footnote 14

Many Egyptians attested in Babylonian sources seem to have been integrated into existing structures in Babylonian society, particularly the royal administration.Footnote 15 This institution appears to have been tolerant towards professionals with a suitable intellectual or cultural background who were not native Babylonians. Not all of these people were necessarily of low rank, as is evident from men such as Ḫar-maṣu, the prison judge, the chamberlain Bagazuštu with his Egyptian patronym (mentioned earlier), and the significant number of bearers of Egyptian names who belonged to the middle strata of administration. Hackl and Jursa suggest that because in the fourth and fifth centuries a higher number of Egyptians were affiliated with the royal administration, and these people represented a large share of the total number of attested Egyptians, this may indicate an increase in absolute numbers of Egyptians present in Babylonia, and of those involved in administrative tasks in particular.Footnote 16

Egyptian names sometimes re-appear in families, even after a generation bore Babylonian names due to their assimilation to the Babylonian society.Footnote 17 One important Babylonian family gave an Egyptian name to at least one of their children,Footnote 18 suggesting that bearing an Egyptian name did not carry overtly negative connotations.

Typology of Egyptian Names

The following discussion pertains to characteristics of Egyptian names and naming practices that are relevant for the time period covered in this chapter. In Babylonian sources we encounter Egyptian names that can be classified into several types. Broadly speaking, there are ‘complex’ names that form (verbal or non-verbal) clauses and ‘simple’ names that do not.

Common Elements in Egyptian Names

Articles

Many Egyptian names start with articles: the definite article pꜢ (tꜢ for female, nꜢ for plural) and the ‘belonging’ article pa (ta for female, na for plural). These articles look similar in transliteration, but differ in meaning. The definite article reflects simply ‘the’ (PꜢ-whr ‘The hound’). The ‘belonging’ article, on the other hand, evolved out of a combination of the definite article with a following genitive -n(.t) in Late Egyptian (for example, in the names PꜢ-n-Divinity and TꜢ-n.t-Divinity for ‘The (male/female) one ‘of’ Divinity’, ‘The (male/female) one belonging to Divinity’)Footnote 19 that resulted in a special orthographic form in Demotic that is distinguished from the definite article in transliteration convention. Thus, the name Ta-I҆s.t means ‘She/the female one of Isis’.

Babylonian scribes do not consistently distinguish between these two types of articles in writing; the articles may have sounded very similar or even identical to a foreign listener when pronounced.Footnote 20 In Egyptian name collections, however, these articles are listed under separate sections in indexes (pꜢ is listed before pa, and tꜢ before ta, etc.).

Divinities

Names that show or express a relationship to an Egyptian divinity are common among Egyptian names found in Babylonian texts. Our perception of exactly how common is likely a little skewed: names including an Egyptian divinity are generally easier to recognise than names without one. However, even in Egyptian sources names with a divinity – theophoric names – are numerous. The gender of a divinity included in a name is not an indicator of the gender of the name-bearer: both male and female names can show male and female divinities.

The distribution of divinities in Egyptian names found in cuneiform material is somewhat uneven: some occur quite often, while some are completely absent, even though they are relatively common in native Egyptian sources.

The Egyptian divinities that occur regularly in the Neo- and Late Babylonian material are I҆mn ‘Amun’ (m), I҆s.t ‘Isis’ (f), and Ḥr ‘Horus’ (m). Divinities that are attested multiple times include I҆tm ‘Atum’ (m), Wn-nfr ‘Onnophris’ (m), Wsi҆r ‘Osiris’ (m), BꜢst.t ‘Bastet’ (f), and Ḥp ‘Apis’ (m). Rarer occurrences are Ptḥ ‘Ptah’ (m), Mḥy.t ‘Mehyt’ (f), Nfr-tm ‘Nefertem’ (m), Rꜥ ‘Ra’ (m), Ḥꜥpy ‘Hapy’ (m), Ḫnsw ‘Khonsu’ (m), and Ḏḥwty ‘Thoth’ (m). Divinities that seem to be unattested in Egyptian names in Babylonian texts so far, but who appear somewhat regularly in Egyptian sources, are I҆np(w) ‘Anubis’ (m), Bs ‘Bes’ (m), Mn(w) ‘Min’ (m), Ni҆.t ‘Neith’ (f), Ḫnm(w) ‘Khnum’ (m), and Sbk ‘Sobek’ (m). This section does not include all Egyptian divinities.

The absence of certain divinities could be due to the fact that names with these divinities were indeed not used by people appearing in cuneiform sources. But it could also be an indication that names with these divinities have not yet been recognised or identified. A name with the divine name Ḏḥwty is instantly recognisable due to its unusual construction *t-h-u-t-(possible vowel), reflected in the name Tiḫut-arṭēsi (Iti-ḫu-ut-ar-ṭe-e-si), Egyptian Ḏḥwty-i҆.i҆r-di҆.t=s, ‘Thoth is the one who gave him’ (BE 9 82:12). By contrast, in earlier Babylonian writings of Ptḥ, the initial -p is usually unwritten, leaving only the phonemes -th for identification (e.g., MB Taḫ-māya, Ita-aḫ-ma-ia, Ptḥ-my).Footnote 21 From Greek writings of the divine name Sbk it can be deduced that this name was actually vocalised as something akin to ‘So̅k’, the middle -b disappearing in pronunciation (cf. DN 914ff.). And due to variations in vowel use in cuneiform writings of Egyptian names, the difference between Mn(w) and I҆mn might be impossible to tell in certain cases, due to their parallel consonants.

In some cases, Babylonian scribes recognised the name of an Egyptian divinity in a personal name and indicated this by giving it a divine determinative. This predominantly happened with the name of the goddess Isis: for example, Pati-Esi (Ipa-at-de-si-ˀ, PBS 2/1 65:23), for Egyptian PꜢ-di҆-I҆s.t, ‘The one whom Isis has given’ (see also section on ‘Hybrid Names’).

Common Words in Egyptian Names

Nouns and adjectives that occur regularly in Egyptian names include wḏꜢ ‘healthy, hale’, ꜥnḫ ‘life, live’, nfr ‘good, beautiful; goodness, beauty’, nṯr, nṯr.w ‘god, gods’, nḫṱ ‘strong; strength’, ḥꜢ.t ‘front’, ḥr ‘face’ (not to be confused with Ḥr, ‘Horus’), ḥtp ‘peace(ful)’, ḫl/ḫr ‘servant, slave’, and šr, šr.t ‘child (m/f)’.

Verbs that occur regularly in Egyptian names include i҆r ‘to do’, i҆w/i҆y ‘to come’, ꜥr/ꜥl ‘to bring’, nḥm ‘to save’, ms ‘to be born’, rḫ ‘to know’, ḫꜢꜥ ‘to leave/place’, ṯꜢy ‘to grab/take’, di҆(.t) ‘to give’, and ḏd ‘to say’.

Non-Clausal Names

These name types include names with an unclear structure and meaning (e.g., Abāya, Ia-ba-a, possibly Egyptian I҆by(?);Footnote 22 Ukkāya, Iuk-ka-a, perhaps Egyptian I҆ky(?)Footnote 23); names that are simply the name of a deity or person and thus essentially a noun (e.g., Ḫūru, Iḫu-ú-ru, Egyptian Ḥr, ‘Horus’); and names that consist of nouns (and pronouns) or nominal constructions (e.g., Paḫatarê, Ipa-ḫa-ta-re-e, Egyptian PꜢ-ḥtr, ‘The twin’, and Ḫarsisi, Iḫar-si-si, Egyptian Ḥr-sꜢ-I҆s.t, ‘Horus son (of) Isis’).Footnote 24

Clausal Names

Some clausal name types consist of a non-verbal clause. An example is the name Amnapi (Iam-na-pi-ˀ), Egyptian I҆mn-m-I҆p.t, ‘Amun (is) in Ipet’.Footnote 25 Notable non-verbal clause names are those formed with ‘belonging’ articles that indicate a person belonging to someone or something: Tamūnu (Ita-mu-ú-nu), Egyptian Ta-I҆mn, ‘She (who is) of Amun’.Footnote 26

Names consisting of a verbal clause include names formed with statives and names with conjugated verbs. A stative name can look like this: Amutu (Ia-mu-tú), Egyptian I҆y-m-ḥtp, ‘(He) has come in peace’.Footnote 27 Verbal clause names with conjugated verbs are relatively common in the Babylonian source material. This is not surprising, as these names are some of the more easily recognisable Egyptian names. Notable patterns include:Footnote 28

- PꜢ/TꜢ-di҆-Divinity ‘The one (male/female) whom Divinity has given’; for example, Paṭumunu (Ipa-ṭu-mu-nu), Egyptian PꜢ-di҆-I҆mn, ‘The one whom Amun has given’.

- Divinity-i҆.i҆r-di҆.t=s ‘Divinity is the one who gave him/her’; Atam-artais (Ia-ta-mar-ṭa-ˀ-is), Egyptian I҆tm-i҆.i҆r-di҆.t=s, ‘Atum is the one who gave him’.

- Ḏd-Divinity-i҆w=f-ꜥnḫ ‘Divinity says: “He will live!”’. No full version of the name is attested yet in Babylonian texts, but a shortened version of the name occurs: Ṣī-Ḫūru (Iṣi-i-ḫu-ú-ru), Egyptian Ḏd-Ḥr-(i҆w=f-ꜥnḫ), ‘Horus says (“He will live!”)’.

Non-Egyptian Names

Names with a ‘Libyan’ origin were regularly used as personal names by Egyptians in the first millennium BCE, as an influx of people from territories to the west of Egypt took place during this time.Footnote 29 A number of pharaohs and local rulers of Libyan descent bore Libyan names during the 22nd, 23rd and 26th dynasties (c. 945–750, 664–526 BCE). The names of these rulers became somewhat popular personal names for Egyptians, and appear in Babylonian texts in this capacity. The meaning of Libyan names is unknown.Footnote 30

Notable Libyan names that appear in Babylonian sources are Ḫalabesu (Egyptian Ḥrbs, in cuneiform, e.g., Iḫa-la-bé-su),Footnote 31 Takelot (Egyptian, e.g., Ṯkrt/Ṱkrṱ; in cuneiform, e.g., Itak-la-a-ta, Itak-la-ta), and Psamtek (Egyptian Psmṯk; e.g., Ipu-sa-mi-is-ki in cuneiform).Footnote 32 Basilophorous Egyptian names may also feature the names of these kings (e.g., Ꜥnḫ-Ššnḳ ‘May (king) Shoshenq live!’, DN 105).

Hybrid Names

Hybrid names that include an Egyptian divinity are attested in the Babylonian sources, but they seem to be limited to the goddess Isis. We find, for example, fAmat-Esi (fam-mat-de-si-ˀ or fa-mat-de-si-ˀ) ‘Maidservant of Isis’ and Abdi-Esi (Iab-di-de-si-ˀ) ‘Slave of Isis’.Footnote 33 Reference ZadokRan Zadok (1992, 142) argues that these people were not necessarily of Egyptian origin, but rather that these names indicated the international popularity of the Isis cult.

There is a single attestation of a hybrid name with a Babylonian divinity along with an Egyptian verbal element, namely Bēl-paṭēsu (IdEN-pa-ṭe-e-su), Egyptian Bēl-pꜢ-di҆-s(w), ‘Bēl has given him’.Footnote 34

Naming Practices

In Egyptian texts from the first millennium BCE, filiation is commonly indicated by the construction ‘X, son (of) Y, his mother (is) Z’ and ‘X, daughter (of) Y, her mother (is) Z’. In cuneiform texts the mother’s name is omitted.

Two further aspects of Egyptian naming practices may be relevant to the identification of Egyptian names. First, Egyptians often bore ‘family names’ that skipped a generation. ‘Papponymy’ – naming a child after the grandfather (or grandmother) – was common, which complicates the identification of individuals in texts with multiple family members. In Egyptian texts, like-named relatives could be distinguished by the addition of a descriptor such as ‘(the) elder’ (ꜥꜢ or pꜢ ꜥꜢ) or ‘(the) younger’ (ḫm or pꜢ ḫm) that followed directly after the name: for instance, *PꜢ-di҆-Ḫnsw pꜢ ꜥꜢ sꜢ PꜢ-msḥ, ‘*PꜢ-di҆-Ḫnsw (“The one whom Khonsu has given”) the elder, son of PꜢ-msḥ (“The crocodile”)’. One can wonder how (pꜢ) ꜥꜢ, which includes the enigmatic phonemes ayin and aleph, would be realised in cuneiform writing. To my knowledge these descriptors are not yet attested along with Egyptian names in Babylonian sources, but there are examples of Greek renderings of Egyptian names, where descriptors were interpreted as a part of the name.Footnote 35

Second, in Egyptian sources Egyptians are seen bearing nicknames or shortened names, as well as multiple names. An example of the former is Rwrw, derived from I҆r.t=w-r-r=w and similar name patterns, which has its own entry in name collections.Footnote 36 Bearing multiple or secondary names was an old Egyptian practice that was revived during the first millennium, when people could take on a ‘beautiful name’ in addition to their first name. These names were often basilophorous,Footnote 37 and could be completely different from a person’s first name: for example, a man Ḥr-sꜢ-I҆s.t ‘Horus, son (of) Isis’ also bore the ‘beautiful’ name Psmṯk-m-Ꜣḫ.t ‘Psamtek (is) in the Ꜣḫ.t’.Footnote 38 Under Ptolemaic rule in Egypt, Egyptian people involved in the Ptolemaic administration or army could take on a Greek name in addition to their given name. Some used their double names in different circumstances: the Greek name or both the Greek and Egyptian name in contexts of administration and bureaucracy, and in formal legal documents; the Egyptian name in informal and personal contexts.Footnote 39 A similar practice may underlie the two names of the man Pati-Esi ‘The one whom Isis has given’, who also bore the Iranian name Bagadāta.Footnote 40

Spelling and Normalisation

Identifying possibly Egyptian names in cuneiform material and linking them to known Egyptian names is not an easy task. This has three causes. First, the exact conversion rules of some Egyptian phonemes are not entirely clear. An overview of established correspondents of Egyptian signs to cuneiform writings can be found in the section on ‘Tools for Identifying Egyptian Names in Babylonian Cuneiform Texts’. The Egyptian signs Ꜣ and i҆/j are enigmatic and the discussion about their interpretation is ongoing. They seem to reflect different phonemes or glottal stops, or remain unrealised, depending on their position in a word or name. Second, while cuneiform writing shows vowels, the Egyptian script does not do so as a rule, although some phonemes such as w, i҆/j, and y function as semi-vowels or indicate the presence of a vowel of unknown quality. It is thus prudent to first focus on discerning consonants when trying to identify an Egyptian name. Third, the Egyptian script is archaising. Even in the cursive scripts, which were closer to the spoken language than monumental hieroglyphs, scribes often tended to maintain the traditional writing of a word even when consonants had undergone a sound change or were lost altogether.

Egyptian vocalisation can in part be reconstructed with the aid of spellings of Egyptian words in other scripts. In the first millennium BCE, these are found in Greek texts from Egypt and in the Assyrian and Babylonian cuneiform material. An additional source used for the reconstruction is Coptic, the version of the Egyptian language and script that follows Demotic. However, Coptic texts appear centuries later than the Greek and Akkadian ones and must be used with some caution when reconstructing earlier phonemes.

Egyptology uses a transliteration system to transliterate both hieroglyphic and cursive scripts. Because the Egyptian script does not reflect vowels and is archaising, this transliteration also does not directly reflect the pronunciation of words. It is rather an artificial tool and ‘code’ to indicate how a researcher reads and interprets the signs that also allows those who are not specialised in a particular language phase to understand the reading.

Egyptological transliteration generally follows the archaising writings of names in Egyptian sources. Thus, the Egyptian name element meaning ‘belonging to’, both written and transliterated as Ns-, was in reality vocalised as *Es/Is- or *S- at the end of the first millennium BCE. This can be deduced from Greek writings of, for example, the name Ns-Mn as Έσμινις or even Σμιν (DN 674).Footnote 41 The Babylonian rendering Isa-man-na-pi-ir (Dar. 301:2, 9), transcribed Samannapir, thus reflects the Egyptian name Ns-Wn-nfr ‘He who belongs to Onnophris’,Footnote 42 which had become (I҆)s-Wn-nfr in pronunciation (in Greek Σοννωφρις), also showing the correspondence of Egyptian -w with Babylonian intervocalic -m(a) (which was realised as [w] in pronunciation).

The common name I҆r.t-n.t-Ḥr-r.r=w ‘The eye of Horus (is) against them’ presents a similar difficulty. It appears as Ίναρως in Greek, and has been identified as Babylonian Inaḫarû, written Ii-na-ḫa-ru-ú.Footnote 43 In pronunciation, I҆r.t-n.t had apparently been reduced to only ‘ina-’. An alternative writing of the name in Egyptian exists: I҆n-i҆r.t-Ḥr-r.r=w (DN 72). The additional element I҆n perhaps reflects an attempt to show the real vocalisation.

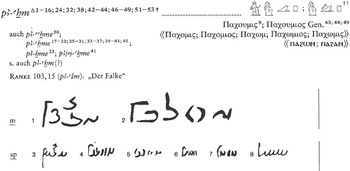

Egyptological name collections and text publications list names in transliteration which reflect the writing of the name in Egyptian. Thus, a conversion of the syllables recorded in the cuneiform version of the name to the equivalent graphemes in the Egyptological transliteration must be made in order to identify a name. The DN provides some assistance here: when known, the Greek and Coptic writing of a name are given (Fig. 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Example of an Egyptian name with additional Greek and Coptic writings.

The Egyptological transliteration of the name in the entry of the DN is PꜢ-ꜥẖm, with alternate writing as PꜢ-ꜥḫme, etc. We can see that the name is also included in Ranke’s ÄPN under PꜢ-ꜥšm (Bd. I 103: 15).Footnote 44 To the right of the name in transliteration, there are examples of the name in Greek and Coptic. Combining the three writings in Egyptian, Greek, and Coptic, we can deduce that the defining phonemes of the name are p-ẖ/ḫ-m. The vowel o is not written in Egyptian, but it is clearly realised in pronunciation, as it appears in the Greek and Coptic writings. The Greek and Coptic writings also consistently show a vowel a at the start of the word, which suggests that this vowel was also pronounced (and was not a ∅ as aleph and ayin may sometimes be; see Table 12.2). It is the defining phonemes, and secondarily the vowels, that should be considered when comparing cuneiform writings of Egyptian names for identification.

Table 12.2 Egyptian graphemes, their corresponding phonemes, and their known correspondents in Neo- and Late Babylonian

| Egyptian graphemes in transliteration | Reconstructed phonological values in Egyptian | Correspondents to phonological values in Neo- and Late Babylonian |

|---|---|---|

| Ꜣ (aleph) | The value of this sign is debated.Footnote a | Exact correspondent(s) in Neo- and Late Babylonian are unknown, likely representing different values depending on the place in the word. Alternatively, these different values can be explained by Ꜣ actually being realised as ∅ everywhere.Footnote b |

| i҆ or j (yod) | Semi-vowel. The value of this sign is debated.Footnote c |

|

| y | Semi-vowel, [y] |

|

| ꜥ (ayin) | [ʕ] |

|

| w (waw) | Semi-vowel, [w]Footnote e |

|

| e | Indicates the presence of an indeterminate vowel. | Indeterminate vowel. |

| b | [p] or [b] |

|

| p; f | [p], [ph], [f] |

|

| m | [m] | m |

| n | [n], or [l] in some words. | n, l, or ∅ |

| r; l | [r],Footnote f [l] |

|

| h | [h] | ḫ or ∅ |

| ḥ | [ħ] |

|

|

| ḫ, or k, q, g |

| s | [s] | s or š |

| š |

| š, s |

| k; ḳ/q; g | [k], [kh], [q], [g] | k, q, or g |

| t; d | [t] or less often [th]; and ∅ in case of a feminine marker ‘.t’ at the end of a word. |

|

| ṯ; ṱ | [t/th] or ∅ at the end of word. |

|

| ḏ | [ṯ]Footnote h |

|

a JPA, 53: realised as [ʔ], [y], or ∅. GT, 273–5: originally a ‘strong liquid’ [r]/[l], gradually weakened and disappeared, becoming a glottal stop [ʔ], but retaining its liquid pronunciation under certain conditions.

b JPA, 36: Realised as [l], [r], or ∅. GT, 263, 273–5: [r], [l], and/or [ʔ], or ∅.

c JPA, 53: Realised as both [ʔ] and ∅. Can also represent a vowel (incl. y) at the beginning or end of words, and a gap between two vowels.

d JPA, 36: Realised as [ʔ], with cognates [ʔ], [y], and [l]. GT, 263: [w], [y], and/or [ʔ], and/or [r], [l].

e JPA, 53: Realised as [w] and a vowel; can also represent a final vowel.

f JPA, 53: Realised as [ɾ] and [l] in some words.

g Suggested by Reference ZadokZadok (1992, 142 no. 33), who notes the name appears as Šmw in Aramaic (Reference VittmannVittmann, 1989, 229). For this name, see DN 1348.

h JPA, 54: perhaps also [ḏ] in some dialects.

Tools for Identifying Egyptian Names in Babylonian Cuneiform Texts

Table 12.2 gives an overview of Egyptian graphemes, their corresponding (reconstructed) phoneme(s), and the known correspondents of these phonemes in Neo- and Late Babylonian. The information in this chart is based on correspondences between Egyptian and Akkadian that have been established in the literature (for this, see the ‘Further Reading’ section).

Additional suggestions for reconstructions of phonological values and correspondents by Reference AllenJames P. Allen (2013) and Reference TakácsGabor Takács (1999) are included in the table notes.Footnote 45 For further study of correspondents between Egyptian and Akkadian and other Semitic languages, these works are recommended.Footnote 46