諸家書多才辭,莫過《淮南》也。讀之令人斷氣,方自知為陋爾。

The various texts of Masters Literature abound with ingenious literary expressions, but none can surpass the Huainanzi. Reading it aloud made me breathless, and only after this did I realize how trifling and narrow I was.

The Kongcongzi 孔叢子Footnote 1

Introduction: Expressing the Inexpressible

The marriage between poetry and philosophy sometimes begs the question of why such a tremendous literary effort has to be expended when one simply wants to make philosophical arguments. In 54 b.c.e., Lucretius wrote his only surviving work, the epic poem De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), which lays out the key doctrines of Epicureanism. Lucretius says in Book 1 of the poem that he chose to circulate these philosophical lessons in verse in order to make his dense philosophical reasoning more palatable, as a doctor smears honey around the rim of a cup of bitter wormwood to trick a child into drinking it.Footnote 2 But in the case of the Huainanzi 淮南子 (The Master of Huainan; c. 139 b.c.e.), one of the most poetic and densely rhymed philosophical texts in ancient China,Footnote 3 its compiler Liu An 劉安 (c. 179–122 b.c.e.), king of Huainan, never explains why he crafted a poetic tome.

One possibility is that its poetic diction serves to facilitate textual performance. After analyzing the poetic language of the Huainanzi, Martin Kern argues that its postface, “A Summary of the Essentials” (Yao lüe 要略; chapter 21), is a fu-rhapsody 賦 that was performed at the imperial court when Liu An paid his state visit to his eighteen-year-old nephew, Emperor Wu 漢武帝 (r. 141–87 b.c.e.), in 139 b.c.e. and presented him with the tome.Footnote 4 His finding has been widely accepted.Footnote 5 Michael Nylan goes further and suggests that “the Huainanzi chapters were performed when first presented to the Han court.”Footnote 6 Yet to say that the promotional postface is performable is one thing, to say that the entire book is a performance text is quite another. Although not only the postface but also all the Huainanzi chapters are poetic and densely rhymed, little or no scholarly effort has been made to prove that all or some chapters of the Huainanzi, in addition to the postface, were also performed. Moreover, the idea that the entire Huainanzi is a performance text may seem counterintuitive. Could such a lengthy text (130,000 words) be performed? Are there any special poetic forms in the Huainanzi that make it particularly suitable for performance? Do poetic forms in a philosophical text convey philosophical meanings?Footnote 7 What could be gained by transforming a philosophical treatise into a performable one? Above all, was textual performance in early China merely the aural presentation of (written) texts,Footnote 8 or could it also be a philosophical activity or spiritual exercise? To answer these questions, this preliminary study focuses on the first two chapters of the Huainanzi, the two early expositions of Zhuangzian philosophy,Footnote 9 which contain some of the text's most striking poetic forms.Footnote 10

Previous research has shed much light on how Huainanzi 1 and 2 allude to, interpret, or, according to Michael Puett, misread the Zhuangzi.Footnote 11 Puett's conclusion is striking, as he argues that by violently misreading the Zhuangzi the authors of the Huainanzi actually claim that they understand Zhuangzi better than Zhuangzi himself;Footnote 12 it is they who “explicate and make universalizable what Zhuangzi intuitively understood.”Footnote 13 Indeed, Zhuangzi's emphasis on intuition is reflected in his distrust of language. According to the Zhuangzi, the Way is something inexpressible. It can be attained only by intuition and/or repeated practice of worldly techniques (such as dissecting oxen). This is why one can find such radical claims as “the great way cannot be spoken of” (dadao bucheng 大道不稱) and “the great argument cannot be put into words” (dabian buyan 大辯不言) in the Zhuangzi.Footnote 14 In other words, the verbal representation of the Way is not sufficient to capture the essence of the Way, let alone allow for the daily praxis of the Way—the ultimate purpose of understanding the Way.

But if language is a necessary evil to transmit the Way to others and to posterity, then the Zhuangzi poses a tremendous challenge to the hermeneutics of its philosophy: how could one explicate and make universalizable the Way with the assistance of language without closing the door to intuitive understanding?Footnote 15 In the following, I suggest that the authors of Huainanzi 1 and 2, in response to the Zhuangzi's challenge, invented several sound-correlated poetic forms that are intended to create a space for intuitive understanding by conveying philosophical messages beyond the lexical level of meaning. Thus, to fully experience the book's philosophical richness, readers of the Huainanzi must move beyond the surface verbal meaning and pay attention to the text's acoustic dimension. More importantly, I show that these carefully crafted poetic forms enable readers to experience, embody, and, above all, enact the Way through vocalization.Footnote 16 In other words, by inventing these poetic forms and transforming the Huainanzi into a performance text, Liu An and his retainers heroically closed the perennial gaps between “knowing the Way” (zhi dao 知道), “transmitting the Way to others” (chuan dao 傳道), and “practicing the Way” (xing dao 行道).Footnote 17 In this light, the Huainanzi's contribution to Chinese philosophy is tremendous, and its originality, which has often been underestimated, is in fact profound.

Rhyme and Mimesis

Rhyme in early Chinese philosophical prose is by now well-documented.Footnote 18 But the reasons why these texts rhyme have yet to be thoroughly explored.Footnote 19 In the following, I show that rhyme in the Huainanzi serves to mimetically represent the subject matters, such as the Way. The vocalization of these Way-related paragraphs thus enables the embodiment of the Way.

Mimetically Representing the Subject Matters

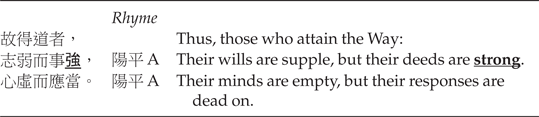

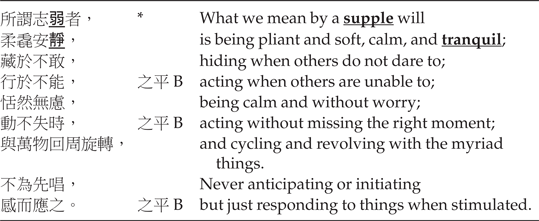

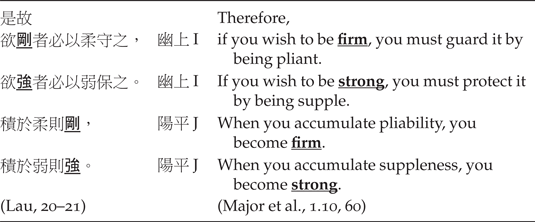

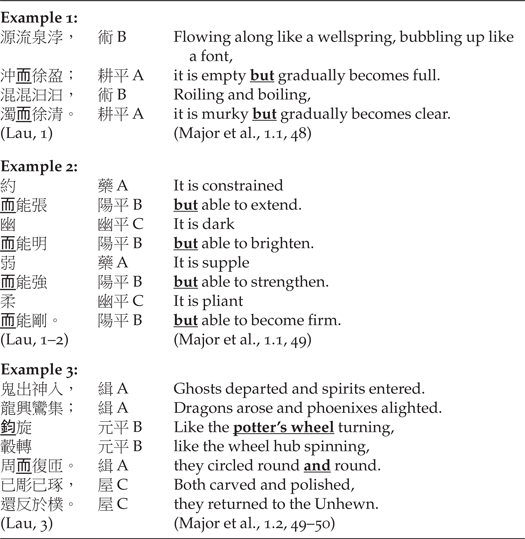

A paragraph in Huainanzi 1, “The Original Way” (Yuandao 原道), states—by evoking the Laozi Footnote 20—that those who attain the Way, despite having weak intent as well as empty and tranquil minds, can always demonstrate strength and efficaciousness when reacting to urgent situations. The paragraph can be divided into five subsections on the basis of the semantic change, rhyme, and introductory markers (gu 故, suowei 所謂, and shigu 是故):Footnote 21

1. Thesis Statement:

2. On Weak Intent:

3. From Being Weak to Being Strong:

4. On Being Strong:

5. Conclusion:

Here, the rhymes convey meanings in at least three ways. First, the beginning of a new subsection is always marked by either a new rhyme (subsection 5) or an unrhymed sentence (subsections 2, 3, and 4; the discontinuities in rhyme are marked by asterisks.) Second, both the thesis statement (subsection 1) and conclusion (subsection 5) of the paragraph are highlighted by rhymes. Third, there is a striking correlation between the density of rhymes and the content in each subsection: the subsections (1, 3, 4, and 5) that contain strength-related words (gang 剛, qiang 強, and li 力) are all densely rhymed, whereas the sole “weakness” subsection (2) is sparsely rhymed. It seems that rhyme serves to mimetically represent the subject matter in each subsection, especially when the text is read aloud. A stark contrast between the “weakness” subsection and the “strength” subsections is created at both the semantic and acoustic levels.

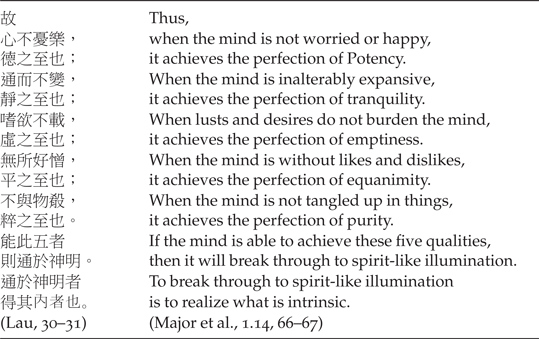

Another paragraph in Huainanzi 1 states that the Way is characterized by tranquility. Thus, people who possess the Way should, as a corollary, possess tranquil minds. To possess tranquil minds, people must not be aroused or distracted by external things. If desires for external things persist, then emotions evolve and disturb one's mind, and eventually, the Way is lost. This Huainanzi paragraph initially seems only to paraphrase the Zhuangzi's teaching that people can enjoy freedom only after they are free from desires for external things.Footnote 22 It can be divided into three subsubsections on the basis of rhyme and meter.

1. Thesis Statement: The Way and Its Deviations

2. On the Harm Brought about by Emotions

3. On Tranquility, the Ideal Mental State

The first subsection presents the thesis statement, which defines the Way by first stating what it is not. The second subsection focuses on the harm brought about by the fluctuation of emotions. The third recapitulates the message of the first, but this time, it directly states what the ideal mental state is. Notably, the second subsection is densely rhymed whereas the first and last subsections are not rhymed at all. Again, a stark contrast is created, but why? I suggest that the highly musical subsection 2, characterized by its dense rhymes, mimetically represents the emotional fluctuations that it describes. More striking is that the A–B–A–B rhyme scheme, as shown in the first four lines of the subsection, perfectly mimics the fluctuation of emotions described by these lines. In contrast, subsections 1 and 3 are not rhymed, thereby mimicking the equanimity prescribed by the two sections. Furthermore, the mantra-like language, the recurrent syntactical patterns (“X 者, Y 之 Z 也” in subsection 1 and “X 不 Y, Z 之至也” in subsection 3), and the anadiplosis (tongyu shenming 通於神明) in these “equanimity subsections” create a repetitive and monotonous aural effect that linguistically mimics (and potentially causes) a stable mental state. In other words, when the entire paragraph is read aloud, readers and audience first intuitively sense and experience mental stability, then mental instability, and, eventually, mental stability.

Mimetically Representing the Nondominant and Circular Way

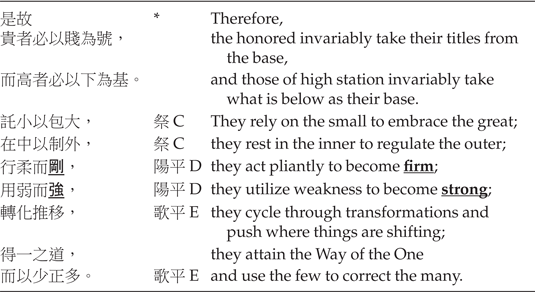

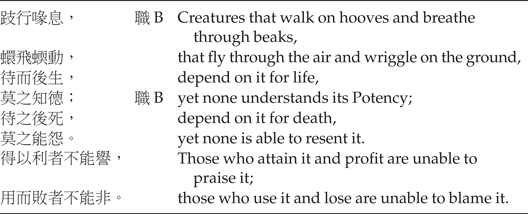

Thus far we know that, from the perspective of human beings, the Way is related to tranquility. Once we possess a peaceful and undisturbed mind, the Way automatically resides in us. But what is the intrinsic nature of the Way, and how exactly does it operate? Huainanzi 1 explains that the Way gives rise to myriad things but does not exercise control over them. At first, the idea once again seems to be nothing more than a commonplace allusion to “Lao-Zhuang” non-action philosophy. It seems that the Huainanzi has contributed nothing original in terms of philosophy. After analyzing the rhyme scheme and metrical pattern, however, the originality of the Huainanzi becomes obvious.

1. The Great Way

2. The Myriad Creatures

3. The Great Way

4. The Myriad Creatures

5. The Great Way

Based on the rhyme scheme and metrical pattern, this paragraph is divided into five subsections; the change in rhyme and meter coincides with and reflects the change in grammatical subject. In fact, the paragraph makes sense only after one realizes that the grammatical subjects of the five subsections are, in sequence, the Way, the myriad creatures, the Way, the myriad creatures, and the Way. In other words, the rhymes are not merely dispensable embellishment; without them, the shift in the grammatical subject becomes much less discernible, and, as a result, the meaning of the entire paragraph may well be distorted.

Still, why did the authors design such a peculiar structure for a paragraph that describes the Way? Why not simply let the Way be the subject of the entire paragraph?Footnote 24 Can the paragraph be paraphrased in a plain and straightforward manner without any loss of meaning? I read the alternation of grammatical subjects, which are emphasized by the changes in rhyme and meter, as a consciously crafted literary form that conveys philosophical meanings. By allowing the myriad creatures to be the grammatical subject in some of the subsections of the paragraph that describes the Way, the idea of the Way being “nondominant,” which is a description presented at the very beginning of the paragraph, is beautifully translated into the parallel linguistic realm: the Way does not dominate the real world that it creates, just as the Way as a grammatical subject does not dominate the paragraph devoted to it. More important, by performing this paragraph aloud, the reciter would activate the embedded rhyme scheme, discern the implicit change of grammatical subjects, role-play both the Way and the myriad creatures, and eventually gain the all-encompassing perspective and actualize the nondominant feature of the Way.

Notably, the paragraph is concluded by a subsection in which the Way is the subject. This concluding remark stands out as being the most densely rhymed of all the subsections. Furthermore, every sentence there ends with xi 兮, a poetic marker of exclamation. In other words, the greatness of the Way is now celebrated through the power of the highly emotional and musical language. This linguistic feature reveals that the nondominant Way is, after all, the ultimate source of and therefore superior to all things.

Curiously, the subject of both the first and last subsections of the paragraph is the Way. This cyclical textual structure emphasizes that the Way is both the source and the normative destination of all things. According to the Laozi,

道生一,一生二,二生三,三生萬物。

The Way begets one; one begets two; two begets three; three begets the myriad creatures.Footnote 25

萬物並作,吾以觀復。夫物芸芸,各復歸其根。

The myriad creatures all rise together, and I watch their return. The teeming creatures all return to their separate roots.Footnote 26

The Way gives birth to myriad creatures, and myriad creatures eventually return to the Way. The textual structure of the Huainanzi passage mimics this cyclicity beyond the immediate lexical level. Readers can therefore intuitively experience how the Way operates simply by reading the paragraph aloud.

The cyclicity of the Way is also expounded in the Zhuangzi. There, the metaphor of a potter's wheel (tao jun 陶鈞), which is circular, is used to describe how the world operates.Footnote 27 The wheel rotates so fast that the distinction between different points on the circumference (which signifies different perspectives and/or myriad things) blurs. The Zhuangzi adds that only those who attain the Way can stay at the center of the circle, remain impartial to various points on the circumference, and remain unchanged and unmoved themselves.Footnote 28 Now, Huainanzi 1 endorses this Zhuangzian insight and frequently invokes the metaphor of the potter's wheel.Footnote 29 As we can see at the beginning of Huainanzi 1, three adjacent paragraphs there describe the circular pattern of change, and all of them show a similar syntactical pattern “A 而 B.”Footnote 30 (Note: er 而 can mean either “and” or “but.”)

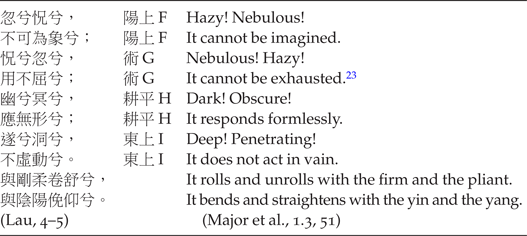

The pattern of the circular movement is only implied in the first two examples and is spelled out in example 3: “like the potter's wheel turning, like the wheel hub spinning, they circled round and round” (鈞旋轂轉, 周而復匝). Note that the recurrent rhyming pattern of these circular-movement-related lines, namely, “the circular rhyming pattern,” is remarkable.

Example 1: BABA (B–A–B and A–B–A)

Example 2: ABCBABCB (A–B–C–B–A, B–C–B, B–A–B, and C–B–A–B–C)

Example 3: ABBA

Admittedly, the rhyming patterns in examples 1 and 3 could be coincidental as “alternating rhyming” (jiaoyun 交韻) (A–B–A–B) is a common phenomenon in early Chinese texts.Footnote 31 Yet, not only the adjacency of the three examples but also the exceptional ABCBA and CBABC patterns in example 2 strongly suggest that the recurrent rhyme scheme is a carefully crafted poetic form. Above all, the circular pattern of rhyming perfectly mimics the circular movement of the Way, which is described by these paragraphs. When the chapter is read aloud, readers and audiences can intuitively experience how the circular Way works. And when they perform these paragraphs regularly (similar to Cook Ding in Zhuangzi 3, who keeps dissecting oxen and eventually understands the Way), they are more likely to internalize and physicalize the cyclicity of the Way. Seen in this light, a text facilitates not only the cognitive understanding of the Way but also its praxis; theory and practice become one. In other words, one understands the nature of the Way and concurrently puts what one learns about the Way into practice during the reading process but not necessarily thereafter; Liu An intended to start a reading revolution.

Meter, Rhythm, and Mimesis

The functions of metrical patterns in early Chinese philosophical prose have rarely been discussed. In the following, I show that the metrical patterns (and nonpatterns) in Huainanzi 2, “The Original Genuineness” (Chuzhen 俶真),Footnote 32 mimetically represent the virtues and encode the process of inner cultivation.Footnote 33

Mimetically Representing the Virtues

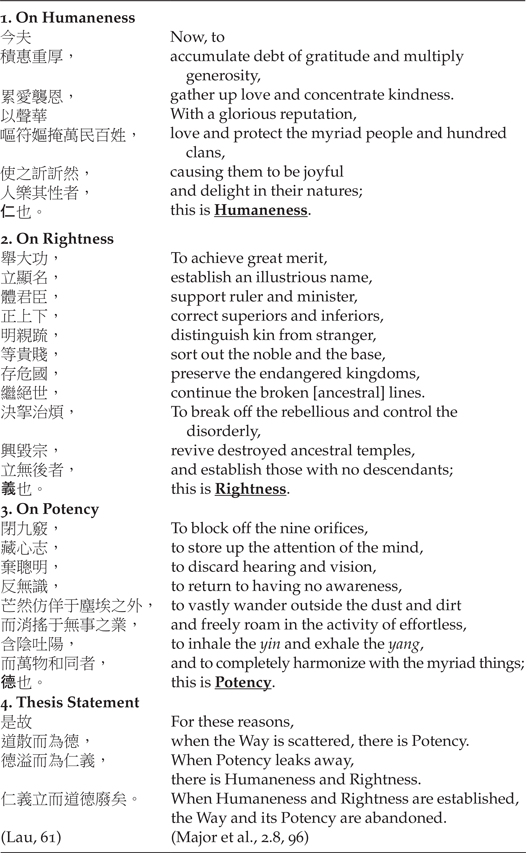

Huainanzi 2 denigrates humaneness (ren 仁) and rightness (yi 義) by claiming that they are derived from the fundamental Way (dao 道) and Potency (de 德):

夫道有經紀條貫,得一之道,連千枝萬葉 … … 是故以道為竿,以德為綸,禮樂為鉤,仁義為餌,投之于江,浮之於海,萬物紛紛,孰非其有!(Lau, 51–52)

The Way has both a warp and a weft linked together. [The Perfected] attain the unity of the Way and then automatically join with its thousand branches and ten thousand leaves … Thus, they take the Way as their pole; Potency as their line; Rites and Music as their hook; Humaneness and Rightness as their bait; they throw them into the rivers; they float them into the seas. Through the myriad things are boundless in numbers, which of them will they not possess? (Major et al., 2.4, 89)

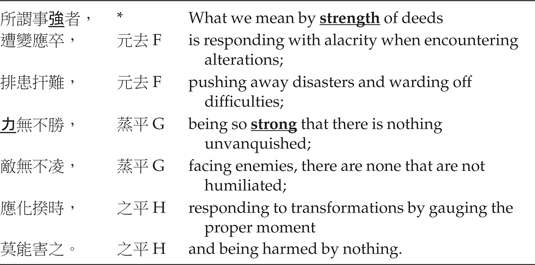

Way and Potency are superior to and therefore more desirable than humaneness and rightness. Again, similar sayings abound in both the Laozi and the Zhuangzi.Footnote 34 The message is also reiterated in the following paragraph in Huainanzi 2, which can be divided into four subsections on the basis of the change in subject matter:

Old Chinese was a largely monosyllabic language: one Chinese character represented one syllable. Thus, the stark contrast in the metrical pattern between subsections 1 and 2 immediately captures one's attention. Although subsection 2 mostly consists of regular trisyllabic units, subsection 1 is metrically looser and less tidy. Furthermore, subsection 2 has a fast-paced and forceful 1–2 (verb–object) rhythm when read aloud, whereas subsection 1 is characterized by the frequent use of reduplicates and repetitive phrases (1. xinxinran 訢訢然; 2. oufu 嘔符, which is similar to yuyan 嫗掩; 3. jihui 積惠, which is semantically similar to zhonghou 重厚, leiai 累愛, and xien 襲恩; 4. wanmin 萬民, which is similar to baixing 百姓), which significantly slows the rhythm of this subsection. Again, one can argue that the contrasts in the metrical pattern and rhythm are coincidental. I will show, however, that there is actually a strong correlation between

1) the contrast in the metrical pattern and rhythm between the two subsections; and

2) the contrast in humaneness (discussed in subsection 1) and rightness (discussed in subsection 2).

To begin with, the difference between humaneness and rightness is succinctly explicated in The Six Virtues 六德, a Warring States bamboo text from Guodian 郭店 tomb no. 1:

門内之治恩弇義,門外之治義斬恩。仁類柔而束,義類持而絕。仁柔而匿,義剛而簡。

In the order within the [family] gates, goodwill holds check over rightness; in the order beyond the [family] gates, rightness cuts short goodwill. The manner of humaneness is flexible and cohesive; the manner of rightness is steadfast and uncompromising.Footnote 35

Put simply, humaneness is lenient, loving, forgiving, flexible, and loosely disciplined. It ties people together. In contrast, rightness is justice-driven, absolute, steadfast, and forceful. In this light, the two contrastive metrical patterns mimic humaneness and rightness respectively: the looser pattern of subsection 1 mimics the flexibility of humaneness whereas the regular and orderly pattern and the resulting vigorous rhythm of subsection 2 aptly mimics the resoluteness and steadfastness of rightness.

In fact, the correlation between moral qualities and aural effects was evident in early China; the two contrastive rhythms discussed above belong to two sound types in the Chinese musical tradition. Specifically, Wang Bao's 王褒 (d. 61 b.c.e.) Rhapsody on the Panpipes 洞簫賦 compares and contrasts “sounds of humaneness” (ren sheng 仁聲) and “martial sounds” (wu sheng 武聲). Wang Bao defines “sounds of humaneness” as “docile and compliant, humble and meek” (優柔温潤): “Their sounds of humaneness are like the mild warmth of a southern breeze, generously dispensing kindness” (其仁聲,則若颽風紛披,容與而施惠). The gentleness of the sounds of humaneness thus captures and mirrors the characteristics of humaneness at the aural level, just as the loose metrical pattern of subsection 1 reflects the flexibility of humaneness. In contrast, in describing “martial sounds,” Wang Bao states that “the morals and lessons contained in its measures and rhythms, correspond indeed to principles of rightness. They surge with fury, are roused to passion—Oh, how like the brave warrior!” (科條譬類,誠應義理,澎濞慷慨,一何壯士) and “their martial sounds are like booming blasts of thunder, speeding swiftly, rumbling and roaring” (故其武聲,則若雷霆輘輷,佚豫以沸㥜).Footnote 36 The swiftness and strength of the martial sounds mimetically represent the characteristics of “the principles of rightness” (yi li 義理) at the aural level, just as the regular trisyllabic metrical pattern and the resulting fast-paced, vigorous rhythm of subsection 2 mirror the steadfastness of rightness.

Mimetically Representing the Process of Inner Cultivation

Nevertheless, one may wonder why subsection 3 of the Huainanzi paragraph under discussion, which describes Potency, encompasses both types of metrical patterns discussed above: the metrical pattern of subsection 3 shifts from being trisyllabic (cf. subsection 2) to irregular and untidy (cf. subsection 1). There are, I suggest, two possible and compatible explanations. First, as mentioned above, both humaneness and rightness are derived from Potency. That is, Potency (the root) gives birth to and encompasses them. Thus, at the linguistic level, subsection 3 (Potency) also encompasses the metrical patterns of both subsections 1 (humaneness) and 2 (rightness).

Second, a notable intertextual parallel suggests that the metrical change within subsection 3 is not arbitrary or coincidental. More specifically, a paragraph in Huainanzi 7, which is also devoted to the explication of Zhuangzian philosophy, is both semantically and metrically similar to subsection 3. Both describe how one can attain the Way.

By juxtaposing the two comparable paragraphs,Footnote 37 one immediately notes that they both begin with four trisyllabic units (part A). Furthermore, part A of both paragraphs emphasizes the importance of self-regulation and restraint. The metrical pattern then loosens in part B. Curiously, part B of both paragraphs contains numerous freedom-related phrases (such as fang yan 仿佯, xiao yao 消搖, zong ti 縱體, and si yi 肆意). Thus, I suggest that the change in the metrical pattern within subsection 3 of the above-noted paragraph in Huainanzi 2, which is an exposition of Zhuangzian thought, beautifully encodes the Zhuangzian cultivation process that is described in Zhuangzi 6:

吾猶守而告之,參日而後能外天下;已外天下矣,吾又守之,七日而後能外物;已外物矣,吾又守之,九日而後能外生。

So I began explaining and kept at him for three days, and after that he was able to put the world outside himself. When he had put the world outside himself, I kept at him for seven days more, and after that he was able to put things outside himself. When he had put things outside himself, I kept at him for nine days more, and after that he was able to put life outside himself.Footnote 38

It is said that one must exercise self-restraint and self-governance at the early stage of cultivation if one is to refrain from external things and remain mentally stable. Once the cultivation reaches a critical point, one eventually gains the utmost freedom—being free from the fear of death—as the boundary between life and death has now been forgotten and obliterated. In other words, one must first be self-disciplined in order to eventually be undisciplined and free. In this light, the change in rhythm within the discussed paragraphs in Huainanzi 2 and 7 mimics the Zhuangzian cultivation process on an aural level: from strictness to flexibility. Above all, rhythm can be contagious.Footnote 39 Thus, in experiencing the process of inner cultivation through vocalization, oral performance, praxis, and the cognitive understanding of the Way once again become one.

All the sound-correlated poetic forms noted above mark the Huainanzi as a performance text; at the same time, their poetic inventions elevate the philosophical depth of textual performance to an unprecedented level.Footnote 40 Vocalization thus becomes an actionable and repeatable spiritual exercise, which facilitates the internalization of philosophical values—in particular, one assumes, for Emperor Wu of Han, the young and impressionable recipient who was known for his appreciation and promotion of verbal artistry.Footnote 41

Reading the Huainanzi in Early China: Evidence from Han shu 44

The modern experience of reading any ancient text is that one silently reads the original text side by side with its commentaries. When one encounters a difficult word or expression, one consults dictionaries. The assumption behind this bookish approach is that if one knows the meaning of every single word in an ancient text, one knows or at least comes closer to the overall meaning of the text.Footnote 42 In this light, the Huainanzi seems a particularly demanding text, which contains difficult phrases and complicated sentence patterns everywhere.Footnote 43 Emperor Wu, however, did not have even a single written commentary in hand.Footnote 44 How, then, could he possibly read and understand it? But could this be a wrong question? What if the Huainanzi was not intended for silent reading only?

The cumulative weight of all the evidence presented above strongly suggests that Huainanzi 1 and 2 are performance texts: the intended aural effect and philosophical implications of these sound-correlated poetic forms could be activated and brought out only by trained reciters fully versed in its linguistic artistry and complexities. One should also bear in mind that not only Huainanzi 1 and 2 but also other subsequent chapters are examples of the Western Han fu-rhapsody,Footnote 45 and that many Han fu were intended for oral performance.Footnote 46 Thus, to fully appreciate the philosophical richness and nuances of the Huainanzi, one should be attentive to its performance context. Admittedly, there is no explicit historical record indicating that the Huainanzi was performed in early China. Consider, however, Liu An's interaction with Emperor Wu, as described in the Han shu:

淮南王安為人好書,鼓琴 … … 招致賓客方術之士數千人,作為《內書》二十一篇 … … 時武帝方好藝文,以安屬為諸父,辯博善為文辭,甚尊重之。每為報書及賜,常召司馬相如等視草乃遣。初,安入朝,獻所作《內篇》,新出,上愛祕之。使為《離騷(傳) [傅]》,旦受詔,日食時上。又獻《頌德》及《長安都國頌》。每宴見,談說得失及方技。賦頌,昏莫然後罷。

Liu An, the King of Huainan, was a person fond of texts and of playing the zither … He invited several thousand retainers and masters of prescriptions and techniques who created “inner writings” in twenty-one bamboo rolls [that is, the Huainanzi] … At that time Emperor Wu was fond of art and literature. Because An was among the uncles of the Emperor, and he was eloquent, erudite, and skilled at literary expression, the Emperor respected him greatly. When responding to An's letters or rewarding him, the Emperor regularly summoned Sima Xiangru and others to inspect the draft before sending it out. In the beginning, when An visited the court, he presented the “inner chapters” [that is, the Huainanzi] that he had created. As they were newly produced, the Emperor liked them and carefully stored them in the imperial library. He then tasked [An] to compose a fu-rhapsody on “Encountering Sorrow”;Footnote 47 having received the order in the early morning, [An] submitted [his composition] by breakfast time. He also presented “Eulogizing Virtue” and “Eulogy on the Inner and Outer Realm of Chang'an.” Whenever receiving An to banquets, [the Emperor] discoursed with him about success and failure and about prescriptions and techniques. They also chanted eulogies, which lasted until after dark.Footnote 48

Elements alluding to oral performance abound: Liu An is fond of both texts and music; the famous fu-rhapsodist Sima Xiangru is called on to review the Emperor's draft letters to Liu An; Liu An himself presents to Emperor Wu a fu-rhapsody on the poem “Encountering Sorrow” and two other performable “eulogies” (song 頌);Footnote 49 and the two men's recitations (fusong 賦頌) last into the night. Above all, the Han shu implies that it was only after Liu An presented the Huiananzi that Emperor Wu requested the rhapsody on “Encountering Sorrow.” Note that only the Huainanzi chapters (Huainanzi 1 and 2 in particular),Footnote 50 not the postface, contain numerous allusions to the Chu ci 楚辭 anthology, in which “Encountering Sorrow” is the central text.Footnote 51 In other words, the chronology given in the Han shu strongly suggests that Huainanzi 1 and 2, which contain numerous allusions to “Encountering Sorrow,” had been performed first. The oral performance must have aroused the Emperor's interest in the Chu ci, and as a result, Liu An was asked to compose (and probably also perform) a rhapsody on “Encountering Sorrow.” Stated simply, both the internal linguistic evidence and contextual information suggest that the Huainanzi was performed at the Han court.

Conclusion: Performativity and Originality

The Han shu passage cited above emphasizes that the Huainanzi was “newly produced” (xin chu 新出). Most likely because of its newness, Emperor Wu liked it very much. Paradoxically, the originality of the Huainanzi has often been challenged by modern scholars as it borrows extensively from an array of pre-existing texts.Footnote 52 Simply put, ancient reader(s) found the text new and exciting while quite a few modern readers found it unoriginal and mundane. How are we to make sense of such a considerable difference in terms of readers’ perceptions between the ancients and the moderns? I suggest that although the Huainanzi often invokes the teachings of Zhuangzi (and Laozi), its originality is manifested in its carefully and beautifully crafted poetic forms. These literary forms not only convey meanings beyond the lexical level but also, perhaps for the first time in Chinese history, allow for the praxis of the Way in the process of reading and recitation. Liu An, having the chance to present the text to Emperor Wu in person, must have demonstrated to him its indispensable performative dimension in extenso. During the subsequent transmission process, however, the sounds were gone, and long live the written text. Not only the original performance context but also the linguistic-performative-philosophical dimension have gradually been forgotten.

Finally, one may ask, did the Huainanzi authors invent these sound-related literary devices only to show off their originality, perhaps out of the anxiety of influence? The answer is yes and no. On the one hand, the authors of the Huainanzi responded creatively to the Zhuangzi's challenge by inventing highly original sound-correlated literary forms to convey meaning in a nonverbal and musical way. On the other hand, they designed these poetic forms precisely because they were heavily indebted to the Zhuangzi to the extent that they followed Zhuangzi's preference for sound and music, as implied by the following passage from Zhuangzi 6.

南伯子葵曰:「子獨惡乎聞之?」曰:「聞諸副墨之子,副墨之子聞諸洛誦之孫,洛誦之孫聞之瞻明,瞻明聞之聶許,聶許聞之需役,需役聞之於謳,於謳聞之玄冥,玄冥聞之參寥,參寥聞之疑始。」

Naopo Zikui asked the woman Crookback, ‘Where did you of all people come to hear of the Way?’ ‘I heard it from Inkstain's son, who heard it from Bookworm's grandson, who heard it from Wide–eye, who heard it from Eavesdrop, who heard it from Gossip, who heard it from Singsong, who heard it from Obscurity, who heard it from Mystery, who heard it from what might have been Beginning.’Footnote 53

It is suggested that music and sound are relatively closer to the Way than words and texts.Footnote 54 I thus speculate that this is precisely the reason why the authors expended so much effort to invent these sound-related literary forms of argument: sound and music convey the Way better than words convey it.

To put it in Zhuangzi-style paradoxical language: the originality of the Huainanzi goes hand-in-hand with the unoriginality of the Huainanzi.