Introduction

The 15th of January 1934 was a sunny winter’s day, with strong and piercing winds. The bazars were unusually busy with villagers who had descended on Darbhanga, Muzaffarpur, Monghyr, and smaller towns across North Bihar for the impending celebrations of Eid and Somavari Amavasya.Footnote 1 Others had just finished lunch and were resting in the winter sunlight when the earthquake threw them off their charpoys at 2.13 pm.Footnote 2 Approximately five minutes later, the built environment of entire towns lay in ruins. The earthquake that became known as the 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquakeFootnote 3 was felt across northern India, with the worst affected areas in Tirhut in North Bihar, the town of Monghyr south of the Ganges, and in the Kathmandu Valley.Footnote 4 Contemporary publications called it by different names, partially depending on the earthquake-affected area covered and its impact, and partially framed according to the intended audience: ‘The Great Indian Earthquake’,Footnote 5 ‘The Indian Earthquake’,Footnote 6 ‘The Bihar Earthquake’,Footnote 7 and, in Nepal, ‘The Great Earthquake’.Footnote 8 The local government’s master narrative of the aftermath’s first year, A report on the Bihar Earthquake and on the measures taken in consequence thereof up to the 31st December 1934, was published by William Bailie Brett in his capacity as relief commissioner in charge of the Reconstruction Department and its Earthquake Branch, set up to coordinate relief and reconstruction work.Footnote 9 In the aftermath, another administrative authority, the Darbhanga Raj, ran its own relief and reconstruction programme, subsequently reported in The Bihar Earthquake and the Darbhanga Raj.Footnote 10 Among the many contemporary publications on the earthquake, the government’s official account and the scientific surveys by the Geological Survey of India (GSI) provide the most detailed accounts of the damage.Footnote 11 Sand deposits and standing water had ruined land, roads, and bridges. Houses and infrastructure in Patna and Jamalpur cracked, tilted, and slumped, as well as in the more remote Darjeeling, where significant damage to houses was recorded, while residents felt the tremors far away in Calcutta and Varanasi, where monuments suffered minor damage. Scientific surveys found the often-wholesale destruction of houses in towns across North Bihar, from Motihari in Champaran in the west to Purnea in the east, due to the specific alluvial land conditions that caused either slumping or tilting of the ground, if not the expected shaking. Buildings considered of best possible quality, for instance the Pusa Institute, relocated to Delhi after the earthquake. Government offices, palaces, temples, hospitals, and offices of the Darbhanga Raj all experienced severe damage. The majority of damaged houses in North Bihar were of the type defined by the GSI as kuccha-pucca;Footnote 12 constructed with ‘mud mortar’, and with little to bind the bricks together, they had collapsed in the central area of the earthquake.Footnote 13 Adding to their fragile structure, numerous additions had been built over time, and to considerable height in the bazars. These most common brick houses, sometimes fixed with mud and sometimes with lime or mortar in the towns, and the kuccha-pucca houses in villages, were the most severely affected, according to Relief Commissioner Brett and the GSI.Footnote 14

While official administrative and GSI publications described the damage and overarching frameworks for the relief and reconstruction programmes, the victims of the earthquake took centre stage in publications by, or in support of, relief funds for them. Many had died in the bazars and survivors were displaced. The official government figure of 7,253 deaths was far less than the approximate number of 20,000 deaths stated by the Bihar Central Relief Committee (BCRC), a civil society organization started by prominent members of the Indian National Congress (INC) in order to collect funds for relief.Footnote 15 The BCRC not only raised funds, but, equally importantly, was a civil society-based committee whose purpose was to organize relief work and distribute aid. As its founders emphasized, although it was not a political organization, several members of the INC had prominent roles on the committee.Footnote 16 The other major fund-raiser to collect aid was the Viceroy’s Earthquake Relief Fund (VERF), under the leadership of the viceroy and locally managed by the governor of Bihar and Orissa. The BCRC and the VERF functioned as the two main bodies for public charity through fund-raising, with the support of collections raised by numerous smaller organizations, associations, and independent bodies or individual donations.

Relief funds framed and depicted the victims they sought to aid in starkly different terms and imagery. Taking the example of the 1934 earthquake, this article calls for a reflection on the complex perspectives to be considered in the analysis of representations of disaster victims. In historical disaster research, the narratives of the victims are often less heard than, for instance, accounts of relief work, aid collections, reconstruction plans, blame games, or new scientific innovations and engineering.Footnote 17 Victimhood is a prominent theme in accounts of contemporary social scientists working in disaster zones, and often central to their stories about recovery, largely because survivors are present and can be surveyed, interviewed, observed, and photographed. One recurrent question in contemporary research is the egalitarian effect of disaster, or if it disproportionally affects the marginalized, poor, or socially vulnerable. In historical documents, however, victims are often generalized as a group, or individualized in narratives that become tropes or representations of the essential disaster victim.Footnote 18 This may be explained by the sources and the actors in aftermaths: outsiders and able survivors produce records as rescuers, administrators, relief workers, planners, security forces, builders, exploiters, and/or as those who victimize and locate blame. In the context of Japan’s modern earthquake history, Gregory Clancey suggests that disaster victims ‘may be the ultimate historical subalterns’.Footnote 19 In the case of the dead, victims’ voices are difficult to recover as a group. The dead, the injured, the traumatized, impoverished, displaced, and devastated offer different forms of physical evidence in the form of bodies, corporal remains, or an absence (missing persons), expressions in art, memorialization of the disaster, and its repercussions in literature and the built environment. Victims still alive, like the survivors in the Bible story of Noah’s ark, are introduced to an audience, while the human and animal bodies of those who drowned in the Flood remain conspicuously absent.Footnote 20 The two categories of victim bear witness to disaster, yet the ability to offer representations of the experience remains with those who survive. This article argues that depictions of victims in texts and images after the 1934 earthquake can be understood as articulations of suffering according to discourses related to contemporary colonial and Indian nationalist politics. By situating the depictions of victims in their historical context and drawing upon literature about the socio-political constructions of victimhood, the article shows how victims were constructed around social or socio-economic belonging, political agendas, and a culturally produced image of victimhood. The images and descriptions of victims who served as cultural representations of suffering were appropriated by relief funds for the humanitarian purpose of collecting aid for earthquake victims.Footnote 21 Although a wide variety of victim narratives exists, this article focuses on the framing of victims in connection with publications in support of aid and relief organizations’ collection of funds. Within this category, publications can be divided into two broad groups of sources with visualizations of the victims, photographs, or drawings and illustrations, some accompanied by explanatory text in semi-poetic prose, others invoking a language that draws upon a political register of victimhood that states the need for relief and donations.Footnote 22 Victim narratives would sometimes be retold by survivors, as in a compilation of survivor narratives in Hindi, describing the terror and suffering they experienced in the earthquake.Footnote 23 Victim narratives appeared in legal assembly sessions, in the images of special newspaper issues on the earthquake, or as sensational photographs of material destruction and death in the newspapers.Footnote 24 In this way relief organizations, government administrators, and newspapers made a narrative of victimhood available to different types of audiences and for different purposes. From a close reading of the images and texts produced for the purpose of fund-raising, this article analyses how the representation of victims provides historical insights into the role of governance and civil society in the colonial period, and within this nexus, the potential making of citizens.

‘And there are political earthquakes’Footnote 25

At the time of the earthquake, Bihar and Orissa still formed a state; they were separated into two administrative areas in 1936.Footnote 26 Orissa had its own share of disasters during the colonial period: cyclones along its coastline, floods, and famines.Footnote 27 Riparian Bihar, the troublesome rivers in the north, and the Ganges, running like a highway through the state, provided much of the texture of socio-economic life in trade and agrarian initiatives.Footnote 28 In the vast state, the towns of Patna and Jamalpur served as administrative and commercial nodes,Footnote 29 while outlying towns were considered backwaters, and a punishment posting for colonial officers.Footnote 30 The Bihar famines, the partly overlapping Bengal famines, and a riverine landscape offering regular boons and catastrophes contributed to an image of the region as unfortunate in terms of visitations by ‘natural’ disasters.Footnote 31 Historians have analysed these events as processes embedded within the larger environmental and social history of the region, where governance has played a major role in turning potential natural hazards into disasters.Footnote 32 Major earthquakes, on the other hand, have occurred at longer intervals in the Himalayas, with the 1897 and the 1950 Assam earthquakes featuring in political histories of Northeast India,Footnote 33 but they remain largely outside of social histories. Before 1934, the last major earthquake affecting Bihar had occurred in 1833.Footnote 34 Eighty years after the 1934 earthquake, the recent 2015 Gorkha earthquake disrupted life in large parts of Nepal, while India was relatively spared.Footnote 35

Historians of South Asia locate the significance of the 1934 earthquake in the context of M. K. Gandhi’s interpretation of the event as divine intervention, followed by Rabindranath Tagore’s retort and their exchange of opinions.Footnote 36 The discussion on whether the earthquake was caused by the treatment of Harijans, as Gandhi referred to the Dalits, or a ‘natural’ phenomenon detached from human actions, has come to be interpreted as representing, on the one hand, so-called traditional beliefs and, on the other, ‘scientific’ views in India at that time. Notably, the attention that Gandhi’s statement and Tagore’s rejoinder attracted in the press, as well as later in academia, can be partly ascribed to the considerable publicity their exchange received, and partly to the historical importance of these two individuals. Their respective views on divine intervention in physical phenomena arguably represented ‘two kinds of rationality, two ideas of science, and two approaches to modernity’.Footnote 37 If Gandhi’s ‘strange use of earthquakes’ was recognized in contemporary media as a form of political pragmatism to address the question of Untouchability,Footnote 38 a less noted incorporation of the earthquake into political rhetoric was made by Jawaharlal Nehru, who used ‘political earthquakes’ as allegories for a government incapable of governance and the consequential revolt by ‘human masses’.Footnote 39 As a barely disguised criticism of British colonial rule, the text was published three months after the earthquake, when Nehru had already served two months in jail.Footnote 40

During the first month of the aftermath, Nehru, together with Rajendra Prasad, had played a central role in the mobilization of relief funds and workers from civil society organizations. While Nehru spent the following three years in jail, the newly released Prasad, later to become the first president of India, became a figurehead for relief work during the first year of the aftermath. Hailing from one of the worst affected areas and active in the INC on local and national levels, he had, like most political prisoners at that time, been sentenced for his participation in the Civil Disobedience Movement.Footnote 41 The movement had successfully spread in 1930–1931, as demonstrations, volunteers going to prison en masse, non-payment of chaukidari tax, and boycott of foreign cloth and liquor stores took place throughout the state.Footnote 42 However, the imprisonment of INC leaders and the counter-actions of the government made many small landholders start to pay chaukidari tax again, and the campaign was brought to an end in March 1931. In January 1932, following the Round Table Conference in London, the Civil Disobedience campaign was again taken up. This time it lasted, in effect, for only three months, as 6,000 Biharis and all of the prominent INC leaders were in jail by March 1932.Footnote 43 At the same time, the 1930s was a period when the INC established itself as a national movement dominated by the bourgeois and better-off peasant groups.Footnote 44 By mid-1933 the Civil Disobedience Movement was winding down and by April 1934, it was called off; but in Bihar, a stronghold for INC action, the government cautiously monitored any possible flare-up of sympathy.Footnote 45 Hence, the collection and distribution of aid began in a politically tense climate.

Three days after the earthquake, Prasad had launched appeals for ‘non-official agencies’ and ‘all Congressmen and women’ to join in the relief work.Footnote 46 The non-official committee he set up was endorsed by ‘prominent Congressmen of Bihar’ to ‘assist and cooperate with other organisations, official or non-official, working for relief’,Footnote 47 on the understanding that ‘in humanitarian work of relief’, Prasad intended to cooperate with any other organizations engaged in relief.Footnote 48 The committee was formally welcomed by the chief secretary to the Government of Bihar and Orissa, ‘provided it works in consultation and cooperation’.Footnote 49 The BCRC was referred to as ‘the Congress fund’, ‘Babu Rajendra Prasad’s fund’,Footnote 50 or ‘The People’s Fund’, which hinted at its popular support.Footnote 51 The committee formed under Prasad consisted of representatives from a range of minor and major relief organizations. The humanitarian initiative was a form of political humanitarianism in the sense that the political aim of its organization and actors was sovereignty from British colonial governance.Footnote 52 Although it was outspokenly not taking a political stance in its relief work, its political affiliation was overtly nationalist in that it was closely associated with the Indian National Congress, whose regional bases it relied on for collecting aid and for the setting up of its relief programme which ran parallel with the local government’s administration.

Nationalist tropes and imagery of the disaster victim

BCRC’s Devastated Bihar: an account of havoc caused by the earthquake of the 15th January, 1934 and relief operation conducted by the Committee was published in March 1934 as a report showcasing for the public the committee’s work programme in the form of data, photographs, and text.Footnote 53 The publication sold for Rs 1, the proceeds of which went towards the BCRC’s fund to ‘help’ ‘the sufferers’.Footnote 54 In the centre of its cover, a crying woman in profile sheds tears over Bihar’s ruined urban landscape (Figure 1). On top and at the bottom, two rows of smaller images depict society before and after the earthquake, showing how it destroyed ‘ordinary’ life in the towns and rural areas. Central to this narrative are not bodies or categories of victims, but the rupture of social life and the consequential suffering that the physical devastation of Bihar meant for residents. The crying woman in profile is central in terms of size and position. She appears devastated, just as Bihar was ‘devastated’ in the title of the publication. Notably, a single woman is suffering, while the public spaces of normality before the earthquake are all populated by men. In the post-earthquake scenarios characterized by desolate ruined spaces, the few human beings in a dejected condition also appear to be men.

Figure 1. Cover of Devastated Bihar: an account of havoc caused by the earthquake of 15th January, 1934 and relief operation conducted by the Committee, published by the BCRC in 1934.

The cover of BCRC’s Devastated Bihar used imagery that this article suggests merged loss and suffering in the earthquake with nationalist symbols. The underlying conceptions of such imagery were derived from a broader cultural understanding of the ‘nation’ and its people. The cover and other publications discussed in this section turned Bihar into a feminine object of rescue using rhetoric borrowed from nationalist depictions of the ‘nation’ and the ‘Motherland’ popular in nationalist discourse of the late nineteenth century. ‘Gendered nations’ became an integral feature in the nineteenth-century history of the state, nationalism, and the formation of the nation-states of Europe, as well as the identities of nation-states emerging from colonized territories.Footnote 55 In the South Asian context, Manu Goswami discusses in depth the iconography of the goddess Bhārat Mātā (Mother India) as religious symbolism and imagery were infused in the nation through literature and political writings during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 56 In a similar vein, Sumathi Ramaswamy analyses patriotism and nationalism in visual representations of maps and languages.Footnote 57 The idea of the modern nation of India was imagined as an ancient goddess, Bhārat Mātā, who embodied ideas and values and served to arouse reverence ‘among her citizen-devotees’.Footnote 58 In so-called ‘barefoot’ cartographic practice, which supplemented the scientific map in the late colonial period and after Independence, Ramaswamy analyses the female personification of the Indian nation and its territory in maps-as-images taking the shape of Mother India or Bhārat Mātā.Footnote 59 In the language movement favouring Tamil as a part of the regional identity, the Tamil language was depicted as the goddess of learning, reading, and literature.Footnote 60 Ramaswamy argues that ‘visual patriotism tries to solve the problem of getting Indians to die for an abstract geo-body named “India” by inserting the image of Bharat Mata into the empty social space of the map of India’.Footnote 61

Contrary to the feminization of suffering on the cover of Devastated Bihar, the content of the publication described the work and leadership of the BCRC as almost exclusively run by men. BCRC’s work in towns and districts across the affected area was documented in text and photographs, accompanied by lists of ‘distinguished leaders co-opted as members’, of other members and office bearers, and the participating organizations, as well as a breakdown of census data from rural and urban areas. The central role of men and masculine qualities were further accentuated by Rajendra Prasad who called on ‘[our] manliness, courage, foresight and determination’ in the relief work.Footnote 62 Notably, BCRC’s Devastated Bihar was one of three publications published in the aftermath that used ‘Devastated Bihar’ in its main title: the other two were a report by Rajendra Prasad and an eyewitness account of Jawaharlal Nehru published by Mohan Lal Saksena (1869–1965), respectively.Footnote 63

As the title of Saksena’s booklet promised, Devastated Bihar through Jawaharlal’s Lenses contained mainly photographs taken by Jawaharlal Nehru, alongside his statements to the press during a tour of the area in the earthquake’s immediate aftermath.Footnote 64 Compared to the BCRC’s report, neither Saksena’s nor Prasad’s publications appear to have been widely distributed.Footnote 65 Saksena’s publication, with numerous photographs and printed on high quality paper in Allahabad, most likely came at a higher price than the BCRC’s report.Footnote 66 Publishing Nehru’s eye-witness account in the form of public statements and photographs was explained in the preface by Saksena as a compromise, since Nehru had not been permitted to send his notes to be published as a report after being imprisoned four weeks after the earthquake. By donating the ‘entire sales proceeds’ of the publication to the BCRC, Nehru was described as continuing his contribution towards relief work.Footnote 67 His photographs of civil society members committed to relief work among the ruins, coupled with his press statements calling on relief workers and for aid, were in support of the relief and reconstruction programme outlined in Devastated Behar: The Problem of Reconstruction by Rajendra Prasad who had contributed a foreword to the booklet by Saksena.Footnote 68 Nehru’s documentation in the form of press statements and photographs was produced in the same period as Prasad had written the slim booklet, which was published first out of the three publications with the same main title.Footnote 69 Contrary to Devastated Bihar through Jawaharlal’s Lenses and Devastated Bihar by the BCRC, it did not include any images and was printed locally on low quality paper by the Searchlight Press. The booklet’s programmatic approach reflected the organizational role Prasad had taken in the BCRC during this initial phase of the earthquake’s aftermath as he listed the tasks to be undertaken, ranging from clearing debris, restoring wells, reconstructing houses, reclaiming land covered by sand or water, to providing food or grains where crops and agricultural fields had been ruined, and aiding professional groups who had temporarily lost their livelihoods. Under the heading ‘Principles of Reconstruction’, Prasad emphasized the resourcefulness of the earthquake victims who wished to participate actively in reconstruction and warned against ‘lulling them to sleep with opiate doses of indiscriminate charity’.Footnote 70 Another section made it clear how ‘no quarter should be given to sloth and slipshod, easy-going habits’.Footnote 71 The cautionary stance towards charitable relief was in line with contemporary attitudes among nationalist Indian philanthropic and social service associations’ view of ‘traditional’ Hindu charity as being wasteful, inefficient, and indiscriminate: Indian charity needed to be ‘disciplined’ and channelled through organized societies.Footnote 72

While all three publications focused on the need for relief and reconstruction, Prasad’s booklet was devoid of the nationalist rhetoric that ran through the BCRC’s and Saksena’s respective publications. Only a cursory mention of ‘our people’ and ‘countrymen’ appeared in connection with the need for skills and resources in the reconstruction programme.Footnote 73 Saksena’s and BCRC’s respective publications, in contrast to Prasad’s booklet, made extensive use of visuals and a nationalist patriotic rhetoric. Both Saksena and Nehru framed the need for aid in a language invoking ‘the nation’. Rather than dwelling on the suffering of those affected, Nehru acknowledged the ability of ‘numerous groups of workers from all over India’ to participate in the relief work, stressing a national unity ‘in the real spirit of service that our people have shown’: ‘The Hindus, the Muslims, the Sikhs, the Christians and others have pulled together and tried to work as Indians face to face with a common disaster.’ His praise of ‘Indians’ contributing to the relief work was further accentuated by his simultaneous criticism of the colonial government’s alleged slow-moving and lackadaisical efforts in clearing debris in order to save lives. According to him, this state of affairs was compounded by not declaring a state of emergency, which could have enabled speedier action.Footnote 74 The emphasis on the central role of ‘the nation’ in carrying out relief work reflected a nationalism that increasingly permeated social service organizations and philanthropic institutionalization in the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 75 Social services and, in this case, aid in the aftermath of a disaster served to give ‘moral legitimacy’ to Indian leaders, further accentuated by an oppositional discourse where the colonial government appeared less capable, if not incapable, of governance.Footnote 76

The visual and patriotic rhetoric appeared in another major publication, issued in support of the BCRC. The Chronicle-Sentinel, a collaboration between two newspapers, the Bombay Chronicle and the Bombay Sentinel, published a special earthquake issue with the title ‘Earthquake Number: Which hand is yours’ (Figure 2) in March 1934.Footnote 77 The two nationalist newspapers supported the work of the BCRC and the editors contributed financially to its fund.Footnote 78 Not unlike the cover of BCRC’s Devastated Bihar, the issue’s front page juxtaposed images of women in distress with images and text depicting a ruined Bihar in their call on ‘the nation’. One of the editors appealed especially to ‘people of Western India’ and the metropole in language openly criticizing the ‘scandalous inertia’ of the government.Footnote 79

Figure 2. Cover of ‘Earthquake Number: Which hand is yours’, special issue by the Chronicle-Sentinel. The editors were Syed Abdullah Brelvi and Benjamin Guy Horniman.

While the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar, like the other BCRC publications, was published by the Searchlight Press in Patna, the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’ was a product of two Bombay newspapers and aimed at the metropole’s readership.Footnote 80 The advertisement for the forthcoming special earthquake issue in the Bombay Chronicle in the first week of March promised texts on the earthquake by M. K. Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, and Rajendra Prasad, among the 34 politicians, administrative officials, and scientists listed as contributors. Further, it promised disaster viewing in the form of ‘descriptive accounts of harrowing scenes’ and being ‘profusely illustrated with photographs of the scene of the disaster’.Footnote 81 On the day of its publication, an advertisement highlighted its pictorial content, emphasizing in bold and enlarged letters that the issue was ‘profusely illustrated’. Coinciding with reports in the same issue urging readers to contribute in order to collect Rs 200,000 to the BCRC, and M. K. Gandhi’s tour of the earthquake area, the advertisement stated that ‘Every member of your Family ought to purchase a copy and thus contribute towards the Fund’, as half of the price of four annas would go to the BCRC.Footnote 82 Both the imagery on the cover as well as the advertisement stressed that donations towards the BCRC was the publication’s principal purpose.

Like Devastated Bihar, the cover of the ‘Earthquake Number’ used imagery of suffering women. In torn saris, kneeling or sitting in the ruins of what was once a brick town, the women were flanked by a human body, dead livestock, a naked youngster, city ruins, destroyed wells, and a river. In contrast to Devastated Bihar, the cover explicitly focused on soliciting donations with the sub-title ‘which hand is yours’ and the image of a collection pot, into which hands are depicted giving coins and notes that are simultaneously being distributed over the landscape and ruins. In texts, gifting was invoked by calling for funds from ‘the nation’. As one of the editors remarked, since the ‘cold-blooded slaughter of the innocents in Jallianwala Bagh no incident has so greatly stirred the minds and so deeply moved the hearts of the people of India’.Footnote 83 In this way, the rhetoric of nationalism connected the suffering of the earthquake victims with one of the most violent repressions of peaceful protests in twentieth-century British India. The statement made the suffering in the earthquake a nationalist cause and the subject of pan-Indian patriotism by juxtaposing it to the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in 1919. ‘Earthquake Number’ specifically called on Congressmen to act, and its content was, to a large extent, written by leading Congress members who repeatedly invoked the nation as the rescuer. The funds collected, in turn, went towards the BCRC, an entity united and embodied by the largely male leadership as the representative organ of relief associations working in Bihar in the earthquake’s aftermath. Similar to the cover of Devastated Bihar, the cover of ‘Earthquake Number’ foregrounded suffering women and the ruins of the built environment made up the central parts of the image. Bihar, in effect, became the woman in need of rescue by the nation, represented by the BCRC whose male membership body was made up of Congressmen taking on the role of relief workers and fund contributors. The photographs accompanying the texts showed ruins of residential houses and official buildings, cracks in the roads, relief workers in action carrying the injured, and portrait photos of the contributing authors. The only depiction of the dead, apart from the bodies on the cover, is a photograph of wrapped corpses laid out along a road after being excavated from the ruins of Monghyr bazar.Footnote 84 The photograph is identical to one published in the Statesman’s earthquake issue on 19 January 1934,Footnote 85 reproduced in a less narrowly cropped format.Footnote 86 Bodies were mentioned elsewhere, for instance in the text under a photograph of non-descriptive rubble and of the remains of a house with a goat in the foreground: ‘Where lies dead under the debris the family of Prof. S. Bose of G. B. B. College, Muzaffarpur’ (Figure 3).Footnote 87 By mentioning the tragic deaths, the affective work of a photograph was activated to communicate suffering.

Figure 3. ‘Where lies dead under the debris the family of Prof. S. Bose of G. B. B. College, Muzaffarpur.’

Even though photography was an available medium to communicate the disaster, both the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar and the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’ used artistic drawings on their respective covers. Photographs of displaced, destitute, and homeless people appeared inside the issue and depicted the hardships of people living in the ruins. In much the same way, photographs of merchants selling their goods on the rubble remains of their shops communicated a sense of loss. The spectacle of wholesale devastation formed a backdrop against which the ordinary tasks being carried out by the vendors were striking. Only a handful images showed victims in distress or as the recipients of aid, for instance by the Ramakrishna Mission. A small photograph placed in the corner of a page in ‘Earthquake Number’ portrayed a small group of women carrying bundles on their heads, accompanied by the text ‘Panic-stricken people leaving their villages for fear of life’. A slightly larger photograph of a group of people in the rubble were described as ‘Homeless people wandering in the midst of the bazar at Monghyr’. Previous research on atrocities and famine relief funds show how photography coupled with text has been an important medium to stir humanitarian action since the late nineteenth century.Footnote 88 One plausible explanation for the lack of suffering humans shown in the aftermath of the earthquake could be that the mobilization of relief workers and funds necessitated the visualization of the disaster and its victims in line with the nationalist rhetoric invoked in the publications. The imaginary victim, a version of the nation in need of rescue, could not be depicted through the medium of photography. In the politics of disaster relief, Congress members and supporters of the BCRC relied on a feminine anthropomorphized construction of the nation for the collection of funds.

The portrayal of Bihar as female was further reinforced by the use of nationalist language in the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’. The feminization of Bihar was not necessarily limited to men’s constructions of the nation, but a trope adopted to produce affect in order to mobilize support among nationalists. Sarojini Naidu, the first female president of the INC in 1925 and a prominent politician of the 1930s, in a short introductory note titled ‘Our Supreme Duty’ depicted Bihar as a physically and emotionally hurt female in need of the nation’s help, the language alluding to the devotion towards ‘her’ by offering ‘service’:

It is not enough that on the first poignancy of Bihar’s anguish and affliction the whole country was moved to render her instant succour and solace. Every hour brings fresh revelation of the magnitude of her disaster and the magnitude of her need. Does it not, therefore, behove us all to make Bihar the central burden of our daily thought and duty and offer her our love and consolation transmuted into unstinted and unceasing service for her redemption from the sorrows and perils that beset her.Footnote 89

The devotional (‘offer her our love and consolation transmuted into unstinted and unceasing service for her redemption’) and at the same time patriotic language (‘central burden of our daily thought and duty’) coupled with ascribing human emotions to Bihar (‘Bihar’s anguish and affliction’) and a physical state (‘her need’) that could be remedied (‘redemption from the sorrows and perils’) served to encourage contributions to the fund based on a nationalist language similar to that communicated by the cover. Naidu’s introductory note was followed by a string of short notes and articles calling on the nation to support the relief work. The rescue of Bihar necessitated a ‘national’ response according to headings such as ‘Rajen Babu [Rajendra Prasad] Appeals for Funds: Task Ahead of Bihar is of Tremendous Magnitude, but God Willing we Shall Face it with Backing of Our Nation’, ‘A National Disaster’, ‘A Calamity Code: All Natural Disasters of a Major Kind in Whatever Province Should be Viewed by the State as National Burdens’, and ‘Country’s Response Still Inadequate: Bihar Minister Urges Further Nation-Wide Effort to Aid Stricken Province’.Footnote 90

Another anthropomorphic and feminized image of the earthquake-victim Bihar appeared inside the issue. The image of a woman carrying a baby juxtaposed with the ruins of a town was made by the artist Pulin Bihari Dutt (Figure 4).Footnote 91 Bihar is described as being in a state of suffering (‘agony’) and the woman appears alone with a baby, while the nation is called upon for rescue under the heading: ‘The Agony of Bihar: The Nation’s Call’. The relief providers in this way became an embodiment of ‘the nation’ with legitimate grounds to act. The text below the image equates Bihar’s suffering to the nation’s suffering: ‘the agony of Bihar is a nation’s agony’, thereby reinforcing the idea that aiding Bihar was a national cause. Relief providers as the embodiment of ‘the nation’ were called on to rescue the ‘woman’, the embodiment of Bihar. However, although the image relied on the same components that appeared on the cover—namely mother, child, and destruction—the arrangement, the physical appearance, and mental state of the woman in this image appear different from the dejected poses of the women on the cover. The imagery here may have communicated a vision of the resurrected mother as a young nation with a bright future. The renewal and rebirth of society’s physical but also moral orders feature frequently as a phoenix rising in disaster literature.Footnote 92 In Bihar, images of victims did not locate blame for the earthquake; however, the suffering woman, the suffering Bihar, needed rescue and a protector.

Figure 4. ‘The Agony of Bihar: The Nation’s Call’, image by Pulin Bihari Dutt, Chronicle-Sentinel, ‘Earthquake Number’, p. 2.

The time of the earthquake—1934—is when Ramaswamy notes the spreading of Bhārat Mātā as an object of patriotism and ‘visual piety’, ‘especially in the context of the Civil Disobedience mobilisation’ and as nationalist politics gained momentum.Footnote 93 Ramaswamy shows how during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the vision of Bhārat Mātā was accepted by ‘secularists’ as an embodiment of the geo-political space India. ‘She’ was often depicted as a mother situated in a globe, with the Indian tricolour or a map delineating the borders of India, thereby turning her devotee-citizens into ‘geopiety’.Footnote 94 The image of Bhārat as a goddess or national space was not infrequently depicted as invaded, raped, and assaulted by foreign rulers, in need of rescue by specifically masculine and upper-caste Hindu political agency.Footnote 95 Yet her secular anthropomorphic state of being was also possible in the later part of the Bengal famine (1943–1944) when ‘she’ would be compared to a mother:

With the promise of a bountiful harvest, was Bengal to turn the corner and did she see ahead of her the prospect of safety? Or, was there any, as yet unknown, danger lurking in the dark future, hatching in the womb of time and ready to descend on a hapless people and smite them again? Would there be a repetition in 1944 of the holocaust of 1943? Would Bengal’s countryside be once again laid waste and strewn with the wrecks of her children?Footnote 96

The gendered discourse of geo-political space in 1944, depicting the land of Bengal as the embodiment of the nourishing mother and the citizens as ‘her children’, featured also in the disaster imagery of 1934. Articles and texts in the two outspokenly nationalist publications after the earthquake—the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’ and the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar—described a woman in need of rescue whom the nation and national relief workers would care for.Footnote 97 As Gregory Clancey notes, directly related to the perception of victimhood is the idea of protection, or a protector. A disaster represents a failure of protection: ‘…disaster victimhood can therefore incorporate a very wide range of attitudes toward the idea of protection—how and why it failed, whether it was possible in the first place (inevitability vs. incredulity), and whether authorities are properly exercising it in the aftermath’.Footnote 98 In this way, the representation of victimhood can be crafted to create a protector or rescuer, or to emphasize the failure of protection. Following this line of argument, the imagery of women as victims in 1934 could potentially form a critique of governance or of social structures. The ability to prevent disaster, or restore the victim to a semblance of life before the fall from ‘normal’, tells us more about the non-victims than the victims, those who come for rescue and pose as the upholders of normalcy, such as, in the case of Bihar in 1934, the relief organizations and the government. A similar, yet differently framed, form of nationalist paternalism appeared after the 1950 Assam earthquake, when depictions of the region in its aftermath served to reinforce a stereotypical image of it as subject to the whims of nature, and therefore in need of care by the central government.Footnote 99 In consequence, by including Assam as a part of India, the aftermath of the earthquake became a site for both nation-building and state-making practices.Footnote 100

Images communicated culturally specific values in the examples above, but it is at the same time important to exercise caution in reading allegorical meaning into literary depictions of female bodies in moments of crisis and social breakdown. Margaret Kelleher observes how in famine depictions, ‘women frequently appear as the sole adult survivor, having outlived their male relatives and now lacking their support, suggest at once a greater resilience and a particular vulnerability’.Footnote 101 This observation pins down two important aspects with regard to the depiction of a female victim, namely the simultaneous representation of resilience and ‘a particular vulnerability’. The adult female survivor as a symbol of resilience is interesting to note in light of Paul Greenough’s book that charts a number of victimization processes in the famine related to subsistence, health, and economic and social status.Footnote 102 Data, mainly collected from relief organizations, show a gender bias in famine victimization: to a great extent women and children were abandoned by the male head of the household as a coping strategy. However, statistics on famine mortality do not show higher death rates of women and children.Footnote 103 The absence of male victims in famine depictions may be interpreted as men having succumbed to hunger, migrated in search of food, or not being a victim of the famine. But if data show that men survived to almost the same extent as women, why did men do not figure in the portrayals of victims and survivors? In the feminine iconography of the famine, Parama Roy notes ‘the juxtaposition of female helplessness/victimization and female resilience’ and relates it to an ideological blend of ‘paternalist compassion and misogyny’.Footnote 104 According to her, the feminization of famine was a representation of social breakdown rather than a crisis of subsistence, as women’s social roles as mothers, daughters, and wives were shed for survival. In analysing depictions of suffering in famines published in Shanghai in the second half of the nineteenth century, Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley builds upon Kelleher’s work on the ‘feminization of famine’.Footnote 105 By showing how images of women for sale not only portrayed the tragic state of affairs but also served as a representation of the crisis to motivate action on behalf of famine victims, she argues that ‘the feminized icons of starvation’ resulted in a feminization of nationalism.Footnote 106 Reforming women’s position in society—and not only saving them from prostitution and physical abuse in crises—became an ethos espoused in the name of the Chinese nation at the beginning of the twentieth century and for decades after the famines had passed.

The feminization of the earthquake in Bihar in 1934 also appears to emerge as a representation of an experience, yet a very different one compared to Kelleher’s and Roy’s respective analyses. The lone and downcast women displayed resilience as the embodiment of Bihar, or of the nation’s endurance and strength amid chaos and breakdown of normalcy (Figure 1, Figure 2). At the same time, the particular vulnerability of a woman, or earthquake devastated Bihar, or the nation governed by colonizers signalled a need for protection. In this way gendered depictions of victims can be traced to a nationalist imagery with patriarchal elements, as well as to a more general use of female bodies that invoked paternalism. As research on the gendered dimension of disaster aftermaths shows, the media to a greater extent depicts and describes women or girls as victims.Footnote 107 Assigned the role of the hapless victim, women are presented as passive receivers of aid, in need of rescue by vigilant men. This dualistic notion of female subordinate status and male power prevalent in media coverage after a disaster is partially reflecting an often gendered reconstruction and relief process. Women are increasingly ascribed caregiving roles within the home, while men are ascribed the role as head of the household and therefore the receiver of financial aid, or they perform in professional roles as rescue workers, emergency staff, and engineers.Footnote 108 On a structural level, socially ascribed roles, for instance gender, appear to be reinforced during and after disasters, as the disaster acts as a ‘magnifying glass’ on society.Footnote 109 The gendered social relations of disasters appear to be strengthened in the aid process, as female bodies in distress and children in need feature as well-known universal themes for aid agencies to evoke generous gifting or ‘paternal funding’.Footnote 110 In the historical context of famine, Kelleher has pointed out, the feminization of famine often took the shape of a lone woman, which she interprets as an individualization of the victim that, similar to the ‘Mitmensch’ effect in research on the Holocaust, would be a human-to-human interaction used to invoke a sense of humanity.Footnote 111 Similarly, media reports on war massacres are noted for not publishing images of the anonymous lifeless or mutilated bodies of the victims in order to communicate suffering, but of the mothers who have lost their children.Footnote 112 After the earthquake of 1934, both the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’ and the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar adopted the imagery of the suffering female as a trope for invoking affect. Images of women suffering to portray victimhood drew upon culturally specific repertoires of women and land that can be traced to images and descriptions used also in famines, on the one hand, and nationalist depictions of a gendered geography, on the other. The cultural representation of suffering after the earthquake merged these two tropes—the female representing the nation in nationalist discourse, and a suffering woman representing social upheaval and distress—in order to invoke an affective response. Both Devastated Bihar by the BCRC and ‘Earthquake Number’ by the Chronicle-Sentinel invoked nationalist and paternalistic language to elicit donations from the general public, specifically from its nationalist-oriented readership. The mobilization of relief rested on contemporary nationalist perceptions of India’s geo-body as a female, most distinctly portrayed in ‘popular’ cartography and in texts with an overtly political agenda. By comparing or juxtaposing the disaster landscape and Bihar, with the imagery of a female in agony, these narratives succeeded in nationalizing the disaster.

Urban destruction: invisible victims, implied victims

In contrast to the use of sketches and prints in the publications discussed above, photographs and moving images of urban destruction and ruined land featured in publications appealing for funds towards the VERF. The affect invested in depictions of Bihar’s devastation in the nationalist press stood in stark contrast to the documentation of ruined buildings used in special issues by an outspokenly government-friendly press, which supported the VERF. Most of the images in the latter were of physical damage, and bereft of people. The spectacle of disaster and the damaged built environment comprise the major themes, rather than suffering human beings. Photography was used by all types of print media in the aftermath, but dominated publications of both the international press and the government-supported VERF discussed below.

Photographic documentation of the earthquake’s destruction shared many similarities with the aftermath of the 1891 Nobi earthquake in Japan, when the use of photography was motivated by scientific questions in order to show a foreign audience the destructiveness of an earthquake from the perspective of budding seismologists. Although the images of devastation from 1891 were not instrumentalized in a call for aid in Japan, physical destruction would be used as a theme in subsequent portrayals of earthquakes.Footnote 113 Still fresh in memory in 1934, was the 1923 Kanto earthquake, when just two weeks after the event thousands of images captured the calamity and were circulated in the national and international media.Footnote 114 Gennifer Weisenfeld argues that by codifying tropes and motifs, images of the 1923 Kanto earthquake contributed to the enduring visual lexicon of disaster and in this way, ‘photographs both produced and became the historical record of the event’.Footnote 115 The extensive photodocumentary coverage of the 1923 Kanto earthquake in mass media, as Weisenfeld shows, asserted a visual authority not only through the diverse perspectives of photography, but also other scientific and technologized modes of visualization, including seismography and cartography.Footnote 116

In 1934, photography served to produce the earthquake as a distinctly urban disaster. Photographs of ruined bazar areas and piles of bricks, and cracks running through the thick walls of sturdy, well-built houses, became some of the most common images to communicate the disastrous impact of the earthquake.Footnote 117 Portrayals of the disaster in the media gave examples of before-and-after images of grand houses, palaces, and, not to forget, Monghyr’s clocktower-cum-gateway, which marked the sudden physical power of the event.Footnote 118 Where the earthquake had caused large fissures in the ground, images of them communicated the destruction of infrastructure and livelihoods as they cut across roads, agricultural land, and polo fields. Sometimes the immense depth and length of the fissures were accentuated by a human posing inside them.Footnote 119 With a head or upper body showing just above the ground, these images seemed not only to illustrate the immensity of the damage, but also how the earthquake-induced transformation of the natural environment changed the conditions for humanly engineered structures. In the official publication on the earthquake by the local government, images of ruined infrastructure and land served to make visual the textual descriptions of how the earthquake had disrupted communication and socio-economic life in the region.Footnote 120 Compared to the aftermath of the 1950 Assam earthquake, when representations of Assam in photographs and newspaper reports depicted the state as a physical space, as a realm of nature rather than of men,Footnote 121 photography in 1934 focused on the destruction of the material and built environment. Photographs documented the damage, alongside pictorial evidence in the form of seismographic records, scientific maps, and aerial photography that circulated internationally.Footnote 122 The visual narrative of urban destruction was accompanied by the local government’s reports, Legislative Assembly debates, and publications by nationalist relief organizations that portrayed the middle class, mostly urban residents, as the principal victims of the earthquake.Footnote 123 The local government’s report by Brett stated that ‘The greatest hardship was undoubtedly suffered by families of the middle class who were unable to do their own re-building or repairs and were not accustomed to a life in the open.’Footnote 124 In Bihar, one of the strongest advocates for relief to the middle classes was the Speaker, Chandreshvar Prashad Narayan Sinha, who belonged to the local elite of landowners in Muzaffarpur and argued for relief to the broad middle classes and opined that the greatest group of potential takers of house loans was the large body of the middle classes inhabiting urban, suburban, and rural areas.Footnote 125 According to the VERF’s chart of disbursements, ‘gratuitous relief’ was, foremost, house reconstruction of various kinds: the largest section was ‘House-building grants’, of about Rs 2.7 million, and grants for house materials and semi-permanent shelters of almost Rs 1 million.Footnote 126 Photography’s documentary function in capturing spectacular images of destroyed houses and ravaged landscape could be used to represent ‘victims’ in publications to raise funds. For relief funds, these photographs were representations of a group of people: ruined houses conflated with the economic, physical, and bodily ruin of urban residents, to be grouped into the relief category of the middle classes.

Unlike the BCRC, which was not only a fund-raising committee but also a relief provider that coordinated numerous civil society organizations participating in relief work, the VERF turned over its collection to the relief programme of local government, and its officials distributed grants from the fund. The first appeals on behalf of the VERF framed its purpose as ‘earthquake relief’ for the ‘Indian earthquake’, importantly, under the patronage of the viceroy.Footnote 127 At Howrah station, the vice regal couple’s first-hand experience of the earthquake resulted in ‘A Shocking Farewell’, according to the Calcutta edition of the Statesman, as the jolt made Lady Willingdon remark, ‘Well, we left Madras in a cyclone, and now we leave Calcutta during an earthquake.’Footnote 128 She intended to start a fund for the earthquake victims; instead the viceroy became the fund’s front figure.Footnote 129 A fund like the VERF was a standard form of institutionalized fund-raising for charitable relief in the colonial period. Viceroys had previously headed similar funds during famines.Footnote 130 In 1905, the viceroy had opened a relief fund after the Kangra earthquakeFootnote 131 and again, after the Quetta earthquake in 1935.Footnote 132 Previous research suggests that the history of ‘state-aided’ charity in the Indian subcontinent goes back to the time when the East India Company administration was socially close to prominent commercial classes of Calcutta, for example, relief organized by the governor-general after a tidal wave in southeastern Bengal in 1822.Footnote 133

In 1934, local government employees could choose to have an amount deducted from their salaries towards the fund, and donations by companies and private individuals were publicly acknowledged in the newspapers. In the international sphere, primarily in Great Britain, ‘Mayor funds’ raised collections that were pooled into the VERF. A week after the 1934 earthquake, the viceroy suggested starting a Mansion House fund in order to increase international subscriptions.Footnote 134 According to John F. Hutchinson, the British government’s preferred means for collecting emergency relief from the public in the 1920s and 1930sFootnote 135 was fund-raising under the patronage of the lord mayor of London, the resident of Mansion House, which had been associated since the 1870s with charitable appeals concerning aid in disasters or times of socio-economic distress.Footnote 136 In 1861 the mayor announced the first international appeal for Indian famine relief.Footnote 137 A number of relief funds from Mansion House had supported miners’ families in Great Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 138 The Titanic Relief Fund (1912–1959) served to provide funds for victims (especially those who were British) and provided long-term financial relief in support of survivors and relatives of the deceased.Footnote 139 Beyond disaster victims in the British empire, Mansion House collected substantial funds for disaster relief in foreign countries, including 6,600,000 gold francs for Japan after the 1923 Kanto earthquake.Footnote 140

In preparation for the inaugural meeting of the Mansion House fund, the Department of Public Information launched a propaganda strategy to stimulate contributions at the end of January. In an attempt at increasing public charity, the director of the department recommended that the VERF issue a fresh appeal, emphasizing, with the support of the findings by the GSI, ‘that the earthquake had been one of the biggest known in history’.Footnote 141 The publicity department’s efforts to revive interest in the earthquake by focusing on the scope of the destruction and magnitude of the earthquake was intended to prompt donations from the British public. In support of the VERF, the India Office organized publicity work for the Lord Mayor Fund to stimulate, in particular, international contributions.Footnote 142 The inaugural meeting on 8 February 1934 was presided over by the secretary of state for India and the high commissioner for India.Footnote 143

The India Office kept a close watch on contributions, and the initial £10,000 pledged at the meeting increased to £40,000 after the meeting. It was anticipated as a popular event for the financial urban elite; the India Office thought that wealthy City people, including bankers, would prefer to give to their Mayor’s Fund, rather than to the VERF, partly because the meeting at Mansion House provided an opportunity to show their contributions.Footnote 144 The public display of giving in the company of powerful patrons was an essential part of the fund’s ability to attract contributions; at the same time, lists of contributors published in newspapers made public gifting available to a wider audience.Footnote 145 The fund continued collecting through appeals to churches, universities, schools, provincial authorities, and various organizations and institutions throughout the country—all institutions expected to amass large funds with the help of their considerable organizational capacities and established networks.Footnote 146 The mayors of Sheffield and ManchesterFootnote 147 pooled their fund collections into the VERF,Footnote 148 and like donors, private individuals, and corporations, they were ‘rewarded’ by having their donated amounts and names announced in the newspapers.Footnote 149 Whether contributing a smaller sum in the box outside Mansion House, or by cheque made out to ‘Indian Earthquake Fund’,Footnote 150 subscriptions from the public were performed in public, where subscribers received recognition for the act.

As the earthquake began to fade from newspaper coverage by the end of January 1934, film screenings as charity events served to bolster the VERF and the Lord Mayor Fund. Similar to the newspapers, these films avoided identifying human beings as victims, yet the absence of humans from the desolate and destroyed urban landscapes was felt in them. In cinemas in India and in London, the screening of a short news reel of the devastation offered spectacular views from the air and walk-through perspectives of the ruined towns. Buildings in ruin, material losses, and sensational damage painted scenes of destruction. One of the first screenings took place in Calcutta,Footnote 151 and two weeks after the earthquake, a film was included in the newsreel on view in England.Footnote 152 It coincided with the opening of the fund by the lord mayor of London, who starred as himself in the so-called ‘earthquake film’ that was to be used as an appeal shown all over Great Britain.Footnote 153 A matinee screening attended by the queen,Footnote 154 and other publicity events organized by the nobility, attracted funds from wealthier sections of society.Footnote 155 For the Indian audience, the viceroy issued a film with an appeal for funds by mid-March, two months after the earthquake.Footnote 156

Like the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar and the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’, the Statesman’s special issue ‘Record of the Great Indian Earthquake’ intended to raise funds for earthquake relief, in this case for the VERF, which in effect meant funds for reconstruction. When ‘Record of the Great Indian Earthquake’ was published in April 1934, subscriptions to the colonial relief funds were low, and it was believed that they would attract less than initially expected, a fact explained by waning news interest in the earthquake, in spite of official pressure on newspapers to publish on the topic.Footnote 157 The use of images paired with text was thereby partly founded on the commercial interests of the popular press, on what would sell, as the earthquake had little news value except as a spectacular and destructive event. When six weeks had passed, senior government officials concluded that the news value of the earthquake had declined so that it was no longer ‘live news’. The remains of the spectacular event—numbers of deaths, material losses, and general stories of suffering—were not considered newsworthy by this point in time.Footnote 158

The cover of the Statesman’s special issue on the earthquake, ‘Record of the Great Indian Earthquake’, depicted a typical scene of urban destruction that could have been taken in Muzaffarpur, Monghyr, Darbhanga, or any of the ruined towns in North Bihar (Figure 5). The issue contained appeals by the governor and the viceroy for the VERF, and part of the sales proceeds of the issue went to the fund over which the two officials presided.Footnote 159 It was published after the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar and the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’, and as an afterthought rather than part of a strategy to raise funds.

Figure 5. Cover of ‘Record of the Great Indian Earthquake’, a special issue on the earthquake by the Statesman.

The issue was first published by the Statesman in Calcutta in April 1934,Footnote 160 and, printed on art paper, it was sold in England for one shilling to an intended audience of ‘people who had lived in India or who have relatives or business interests there’.Footnote 161 The Statesman’s London manager, in marketing the publication in England, promised ‘amazing pictures of the earthquake’ as ‘a pictorial record of one of the greatest disasters in Indian history’.Footnote 162 The earthquake as an event and the spectacular destruction that resulted, rather than the suffering of those affected, served to sell magazines and thereby collect funds on behalf of the VERF.

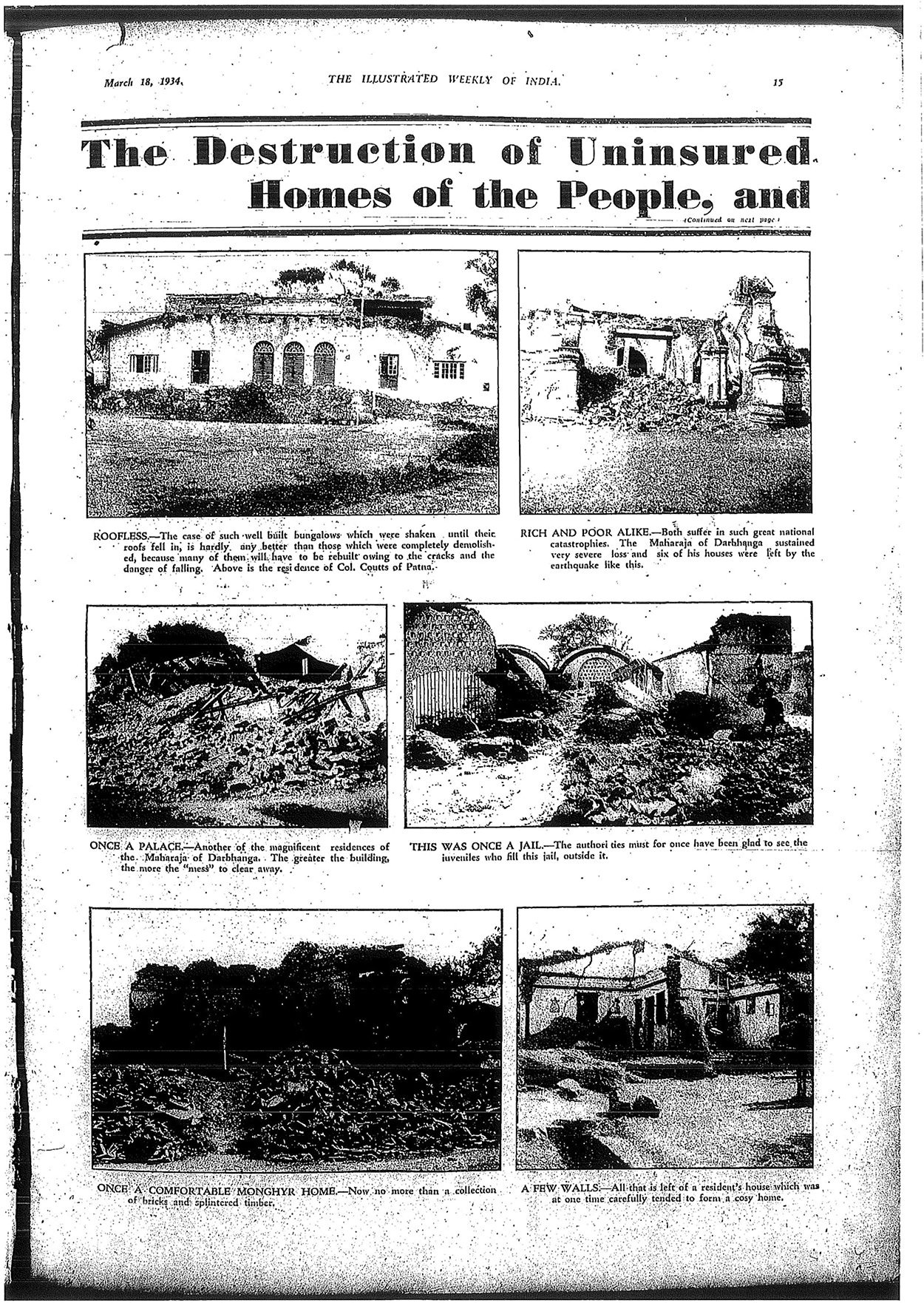

Private British business interests in the concrete industry, represented by H. E. Ormerod, also urged the government to use images of material destruction to increase relief funds in March 1934. The proposition involved a budget, a set of photographs, and a committee for propaganda work, consisting of, among others, the editors of the Statesman and the Times of India. Local government declined to be part of such a committee, partly because it would not be directly connected to them,Footnote 163 and partly because the initiative was seen as coming too late.Footnote 164 The images of near-total destruction in Monghyr suggested for propaganda work in March 1934 were consequently published by the Indian Concrete Journal in its special issue titled ‘The Great Indian Earthquake’ in October 1934,Footnote 165 and some also featured in the local government’s report on the earthquake.Footnote 166 Before that, some of the images appeared in a special earthquake issue of the Illustrated Weekly of India in Bombay, which published eight pages of photographs from the same series in conjunction with an appeal for the VERF (Figure 6).Footnote 167 Like the other issues dedicated to the earthquake and the collection of relief funds, it was published in March 1934. The eight pages of photographs were arranged according to themes, ingeniously linked by headings that formed a poem, and can be seen as an attempt at an emotive as well as descriptive portrayal of people’s suffering through photographs of material and urban destruction. On the first page ‘An appeal to world humanity’ asked for contributions to the VERF, and on the last page, readers were asked to contribute directly to the VERF in New Delhi.

Figure 6. ‘The Destruction of Uninsured Homes of the People, and (…)’.

The Illustrated Weekly of India used imagery and photographs of urban material destruction to communicate suffering (Figure 6), a disembodied approach compared to the anthropomorphic images of Bihar in the BCRC’s Devastated Bihar and the Chronicle-Sentinel’s ‘Earthquake Number’. Human beings did feature in the images, but their physical presence did not appear central for communicating human suffering. Under the image heading ‘When the earth yawned’, the depth of a fissure is illustrated by ‘a youth’ posing inside it; under the heading ‘Still smiling’, the text accompanying an image of two men reconstructing what appears to be a smaller residential building describes how, although ‘poor and hard hit’, the ‘brave reactions to a terrible calamity has to be seen to be believed’.Footnote 169 Only on the last page, under the heading ‘Destitute’, does an image of ‘sufferers’ appear in the form of a large group being administered relief from ‘the earthquake fund’, presumably the VERF’s. Notably, the text does not dwell on their suffering. Instead it warns of the abuse of charity, a statement in line with the official colonial stance against ‘indiscriminate relief’, which was thought to encourage indolence:Footnote 170 ‘One of the problems is to prevent such charity from being abused, and those in charge make very close investigations into circumstances.’Footnote 171 Images of what had been ‘property’, the ruins of grand residential houses destroyed in ten minutes, illustrated the loss of Mr S. M. Naimtullah. As the text accompanying the images alluded to, ‘Fifteen Acres of One Man’s Property Gone’; the lost buildings, such as a zenana and a mosque pictured, were allegedly uninsured, except for a club house, as were the ‘magnificent residences’ of the maharaja of Darbhanga, ‘a cosy home’, and ‘a comfortable Monghyr home’, all reduced to piles of bricks (Figure 6).Footnote 172 These descriptive texts accompanying images of ruins emphasized not just the loss of ‘homes’, which implied intermittent displacement and a loss of security, but also the loss of ‘property’ and thereby the property owners suffering financial losses.

How then can we understand the widespread omission of bodies and people in these publications? Calls for imperial and British contributions to famine relief funds, on the contrary, frequently made use of bodily suffering in their appeals. In the context of British humanitarian political economy in famines, Andrea Major draws attention to Catherine Hall’s seminal book Civilising Subjects in a discussion on how gendered depictions of starvation emphasized the trauma of mothers unable to nourish their children.Footnote 173 In Hall’s words, the female body appealed as a ‘personal body’ to invoke sympathy from audiences beyond racialized distinctions and social divisions.Footnote 174 Arguably the imagery of suffering used in the media until then differed significantly between the two types of disasters. According to Gennifer Weisenfeld, since the 1923 Kanto earthquake, earthquakes had been inscribed as an urban and ‘modern’ disaster in printed sources.Footnote 175 Visuals of emaciated bodies or bones strewn along the roadside during famines could be viewed as protracted suffering where the humanitarian could provide succour directly to the human body.Footnote 176 The sudden and often crushing force which killed in an earthquake could not display the same and known type of prolonged bodily suffering, nor could it be prevented with aid. In an earthquake’s aftermath, suffering the loss of property could, however, be ameliorated by financial or material aid.

Photographs of earthquake damage in the Statesman’s special earthquake issue were primarily used in attempts to raise affect by comparing the physical destruction and the resultant human suffering to European experiences of war. In the issue, appeals relied upon themes and groups of victims with whom a British audience could identify. The extraordinary earthquake destruction became an effective means of creating a ‘spectacle of suffering’ when the particular local cause was communicated to a wider, even global, audience.Footnote 177 These publications, with depictions of urban destruction, appear to have targeted an audience in cities outside the earthquake area, the urban elites in Indian metropoles, and readers in Great Britain who formed part of their readership. The appeal by the viceroy in the Statesman’s ‘Record of the Great Indian Earthquake’ spoke directly to an intended British audience by comparing the destruction in Bihar with that of towns on the Western Front of the First World War.Footnote 178 Such comparisons of destruction and analogies of suffering went beyond the primary importance of material losses. It aimed at empathetic identification with the victims. The spectacle of suffering in this case not only called for pity, it also generalized and compared the suffering of earthquake victims with that of war victims. In effect, such depictions of victimhood translated suffering in order to raise affect for the victims among distant audiences. Charles Schenking has pointed out the comparison of earthquake destruction with the imagery of war in the aftermath of the 1923 Kanto earthquake as a means to elicit a commitment to help.Footnote 179 As in Japan, material destruction, whether caused by war or earthquake, was known to the audience in Great Britain, and created a visualization of suffering shared with the earthquake victims. In order to invite a commitment to help, the effect of disaster was communicated in a manner that made the suffering familiar to the intended audience.Footnote 180 Another way of directly invoking help from Great Britain in the Statesman’s ‘Record of the Great Indian Earthquake’ was to emphasize the financial troubles of the sugar-cane growers, a large European community in North Bihar whose factories had suffered damage in the earthquake.Footnote 181 Planters formed a well-known community of Europeans in India, and their financial hardships became a distinct object for sympathy for readers in Great Britain.Footnote 182

Compared to the press in India, the geographical and social distance between victims and newspaper readers in Great Britain played a role in invoking a form of paternalistic imagery of victims. As opposed to the local disaster, where the presence of victims is felt in order to invoke sympathy, victims of distant disasters are often framed as a general group of unfortunates. The media reports of victimization as collective suffering from the earthquake’s material destruction, rather than individual suffering, reflect a ‘politics of pity’.Footnote 183 Instead of invoking compassion where the local presence of the sufferer is felt, the politics of pity becomes a way of framing the disaster as an event where the suffering victims cannot be questioned, and the urgency of action prompts gifting.Footnote 184 The geographical distance of foreign audiences became apparent in the publicity work surrounding the VERF. With regard to the less-than expected contributions to VERF, the Government of India noted that the British public was frequently accused of giving more liberally to a foreign country, for example, to Japan, than to ‘their own dependency’.Footnote 185 The government initially expressed high hopes that the earthquake would attract donations comparable to the 1923 Kanto earthquake, when Japan had received Rs 25 million (or two million pounds sterling) from the international community.Footnote 186 After the 1905 Kangra earthquake, which was far less devastating compared to the scenario in Bihar, the VERF received about Rs 20,000 from Japan, and Rs 1.5 million from London, as well as donations from Ceylon.Footnote 187 Donations from the British public—‘in aid of the fellow citizens of the Empire’—as the Statesman put it,Footnote 188 disappointed those who may have expected more sympathy or solidarity from the British public than the disappointing fund contributions reflected. By mentioning the ‘dependency’ as the receiver, the government had implied a hierarchical relationship between the British public and the colonial subjects that was expected to stimulate donations. The pronounced expectations for imperial contributions reflect what has been argued in previous research on famine relief for India by British citizens and imperial subjects. As Christina Twomey and Andrew J. May show, disaster relief defined colonial relationships. It both underscored loyalties within the British empire and clarified relationships among colonial people.Footnote 189 Contrary to expectations, the imperial relationship of India as a dependency had not elicited ‘pity’ transformed into charity. Or, according to Luc Boltanski’s line of argument, charity based on a communitarian bond, or sense of commitment among the British public towards the dependency, did not manifest, despite the publicity campaigns targeting foreign and British audiences.Footnote 190

The depictions of ruined houses and infrastructure can thereby be interpreted in two not mutually exclusive ways. One interpretation sees the images as part of a politics of invisibility, depicting material destruction and thereby silencing the dead, wounded, and displaced residents. A large part of earthquake relief focused on property owners, who were considered financial victims of the earthquake, by extending so-called house loans at low rates and grants for reconstruction.Footnote 191 However, in the bazar areas of Monghyr and Muzaffarpur in particular, which experienced very high death tolls, a large number of the surviving residents were sub-tenants ineligible for financial compensation.Footnote 192 Leaving out the bodies or narratives of those who had died or survived effectively erased them from being victims of the earthquake, as they were not the intended recipients of aid. Another way of interpreting the imagery of destroyed buildings reads them as symbolic representations of victimhood of the propertied middle-class victims who suffered financially by losing valuable property and rental incomes. In this way, urban destruction primarily became a symbol of middle-class suffering. Not only the middle-classes’ financial loss in the form of destroyed properties, but also the loss of lives was implied by the images of ruined houses. The use of photographs and its documentary imagery of urban destruction communicated victimhood to an imperial and international metropolitan audience.

Conclusion

As discussed in this article, to a great extent the depiction of victims after the 1934 earthquake relied upon established notions of victimhood, rescuers, and protectors. By portraying the earthquake victim as a suffering woman, depictions played upon notions of a feminized nation that had been established in nationalist discourse. In addition, urban devastation, in particular ruined brick houses and damaged infrastructure, rested on a universal urban imagery of destruction, easily recognizable in an international context. Decontextualized and depersonalized, it appeared as if it could have happened anywhere, to anyone. This article concludes that in 1934, depictions of victimhood and victims did not relate to a specific group of relief recipients. Multiple constructions of victims emerged in parallel discourses that helped to argue for political and social agendas, transgressing the disaster experience. Contrary to being perceived as equalitarian in its havoc, the earthquake’s material destruction in towns made the urban middle classes into ‘true’ victims, depicted as losing material assets, as well as their urban livelihoods, which essentially defined their identity as a socio-economic group.

In the aftermath of the 1934 earthquake, at least three scenarios emerged for how historical and social processes contribute to depictions of victims. First, previous conceptualizations and depictions of victims, regardless of disaster type, may be drawn upon in the construction of a victim identity. The framing of victims in the aftermath seems to have been created based on tropes of victimhood, rather than derived from experiences and memories of suffering in the earthquake, past earthquakes, or ‘natural’ disasters. The feminized disaster victim in publications in support of nationalist relief fund collections relied on previous portrayals of victims in this way. Pre-existing tropes recognized in contemporary social conceptions and political discourse—feminized land and feminized victims—merged with the characteristics of the disaster, that is, damaged land, to mediate the earthquake victim.

Second, the type and nature of a disaster matter in the sense that a sudden or a slow-moving disaster, or a disaster exerting great destructive force on nature and built environments, allow for different types of victim imagery. Rather than seeing the emergence of social and political categories of relief recipients as the direct result of the disaster’s effects, the specific experience of the destruction of land, property, and social disorganization played a large role in shaping projections of victimhood. For instance, in the colonial narratives of victimhood, suffering in Bihar would not be represented foremost by dead bodies or people dying, but with photographs and films of destroyed urban landscapes. In this context, photography had the power to humanize suffering without putting human beings in the frame, as compared to, for instance, famine photography when the suffering bodies were in focus to communicate and humanize suffering.Footnote 193 Research in the humanities on victims may therefore carefully consider the cultural construction of disaster according to contemporary and historical contexts. Third, social and political interests may construct victimhood as a suitable mirror for the construction of a protector identity. The victim portrayed is not necessarily the de facto victim of the disaster, but reflects the identity of the relief organization or, as Didier Fassin puts it, humanitarianism produces the victim.Footnote 194

A question derived from this article is why victimhood may rely on tropes from previous disasters in one specific type of disaster, but less so in the case of another kind of disaster. Can the categorization of a disaster victim lean upon other, broader socio-cultural configurations of suffering, conflating the emotional span that, for instance, martyrs or war victims occupy, along with victims of ‘natural’ disasters?Footnote 195 It should be underlined that the unpredictable nature of how these factors combine is itself a point to take into consideration.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful for comments by colleagues in the conference ‘Epicentre to aftermath: political, social and cultural impacts of earthquakes in South Asia’ (11–12 January 2019, SOAS University of London) where an earlier version of this article was presented. I am also grateful to Cécile Stephanie Stehrenberger for introducing me to a range of literature on body politics in disasters research. Discussion at the conferences ‘The transculturality of historical disasters: governance and the materialisation of glocalisation’ (3–5 March 2011) and ‘Imaging disaster’ (1–3 March 2012) organized by the research groups Cultures of Disasters and Images of Disasters, respectively, in the Excellence Initiative ‘Asia and Europe’ at Heidelberg University were also helpful for developing ideas that appear in this article. I am very grateful to the three reviewers of MAS for their incisive and helpful suggestions.

Competing interests

None.

Author biography

Eleonor Marcussen is a Researcher in History at Linnaeus University and a member of its Center for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies.