Intended use

This document introduces and explains common implementation concepts and frameworks relevant to healthcare epidemiology and infection prevention and control. It focuses on broad behavioral and socioadaptive concepts and suggests ways that infection prevention and control teams, healthcare epidemiologists, infection preventionists, and specialty groups may utilize them to deliver high-quality care. This article can be used as a standalone document, or it can be paired with the manuscripts of the “Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2022 Updates,” which provide technical guidance on how to implement prevention efforts for specific healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

Implementation concepts, frameworks, and models can help bridge the “knowing–doing” gap, a term used to describe why practices in healthcare may diverge from those recommended according to evidence. It is not comprehensive; it guides the reader to think about implementation and to find resources suited for a specific setting and circumstances.

It also is not intended to be prescriptive. Implementation as a concept is broad, and success in implementing practices or interventions depends on a systematic approach matched to an organization’s context (ie, local factors, such as operational support, informatics resources, experience, willingness to change, safety culture, and others). This guidance and the HAI-specific Compendium articles’ implementation sections are meant to be a practical starting point to orient readers to concepts and ways to seek further resources. We do not comment on the success or sustainability of any method and refer the reader to resources, including tools and practical tactics, to help with implementation efforts.

Methods

This article was researched and written by representatives from each Compendium author panel as well as implementation and healthcare epidemiology subject-matter experts, Dr. Kavita Trivedi and Joshua Schaffzin. Unlike the HAI-prevention articles in the “Compendium of Strategies to Prevent HAIs in Acute Care Hospitals: 2022 Updates,” this Compendium article is not based on a systematic literature search specific to its topic. Instead, the overview of implementation and selection of models, frameworks, and resources is based on implementation articles identified through (1) the systematic literature reviews conducted for each HAI-prevention Compendium section, (2) expert opinion and consensus, (3) practical experience, and (4) published research and resources retrieved by the authors.

Rather than providing practice recommendations, a sample of implementation models and frameworks is provided, selected for their track records in published research, utility in advancing infection prevention and control goals, and/or widespread or broad-based applicability relevant to infection prevention and control aims. A glossary of terms relevant to implementation methodology is also provided.

This document was drafted via email correspondence and video conferences among the authors, and its content was approved by electronic vote. The Compendium Expert Panel of members, with broad healthcare epidemiology and infection prevention expertise, reviewed the draft manuscript. Following review by the Expert Panel, the 5 Compendium Partner organizations, professional organizations with subject-matter expertise, and CDC reviewed the document and submitted comments. After revisions by the authors, it was reviewed and approved by the SHEA Guidelines Committee, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee, the American Hospital Association (AHA), and The Joint Commission, and the Boards of SHEA, IDSA, and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

All panel members complied with SHEA and IDSA policies on conflict-of-interest disclosure.

Rationale and statements of concern

The fields of infection prevention and healthcare epidemiology protect patients and the healthcare personnel (HCP) who care for them from HAIs and other safety risks through evidence-based best practices to improve population health and safety. Reference Gerberding1 Sustained infection prevention relies on lasting adherence to these practices to achieve desired outcomes, accountability in the process, and the application of methodologies to monitor and evaluate knowledge and performance. Regulatory authorities like the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 2,3 as well as accrediting organizations like The Joint Commission 4 and DNV, 5 require implementation of organizational policies and stated practices, which they have incorporated into survey expectations. 6,7

Eccles and Mittman Reference Eccles and Mittman8 define implementation science as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice.” Implementation science emerged in the last 20 years to improve patient outcomes and HCP safety. Reference Neta, Brownson and Chambers9,Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger10 As a field of study initially developed for industry, its principles have been adapted to integrate evidence-based practices sustainably in healthcare settings. Implementation science identifies generalizable methods and frameworks to increase the utilization of evidence-based interventions deliberately and systematically in healthcare. Various terms have been used to describe the field of implementation science, including the ‘theory-practice gap,’ ‘knowledge transfer,’ and ‘knowledge utilization.’ Reference Saint, Howell and Krein11 Simply put, implementation science provides the tools and frameworks to help translate evidence-based interventions into everyday clinical practice.

Studies in implementation science make it clear that identifying effective interventions is a necessary first step and that transferring them into real-world settings requires an intentional process. Education and training have proven necessary but insufficient for improvement and behavior change. Implementation science directs us to evaluate contextual determinants of behavior to design more successful, customized interventions. Improvement science, a related field, focuses on the local context and provides guidance regarding how to perform trials of new practices rapidly and iteratively to improve care. Reference Leeman, Rohweder and Lee12 These two fields, while having distinct models and terminology, can be aligned and complement each other to improve healthcare services. Reference Leeman, Rohweder and Lee12

HCP and teams often are unable or unprepared to implement best practices given the idiosyncrasies and complexities of healthcare settings. Reference Houghton, Meskell and Delaney13 Identification and application of multifaceted strategies are necessary to ensure progress toward improvement. Reference Ali, Farley, Speck, Catanzaro, Wicker and Berenholtz14,Reference Wolfensberger, Meier, Clack, Schreiber and Sax15

Strategies for implementation

Determinants

Foundational to any implementation effort is understanding factors that promote or hinder change. Promoting factors are called ‘facilitators’ and hindering factors are ‘barriers.’ Determinants of these factors may be individual, such as the preferences, needs, attitudes, and knowledge of HCP, hospital leaders, patients, and visitors. An individual may be a strong, engaged leader (a facilitator) or an unengaged obstructor (barrier). Determinants may include a team’s composition or ways of communicating, an organization’s culture and capacity, or a system’s policies and resources. Reference Aarons, Hurlburt and Horwitz16 Organizationally, implementation may be facilitated or impeded by expectations and allocation of time (eg, competing priorities, data collection burden, provision of time to dedicate to an effort, fast turnaround at the expense of sustained processes), resources (eg, ease of adapting the EMR, staff capacity, and turnover), and leadership support Reference Saint, Kowalski, Banaszak-Holl, Forman, Damschroder and Krein17 or follower buy-in. Reference Saint, Kowalski, Banaszak-Holl, Forman, Damschroder and Krein18

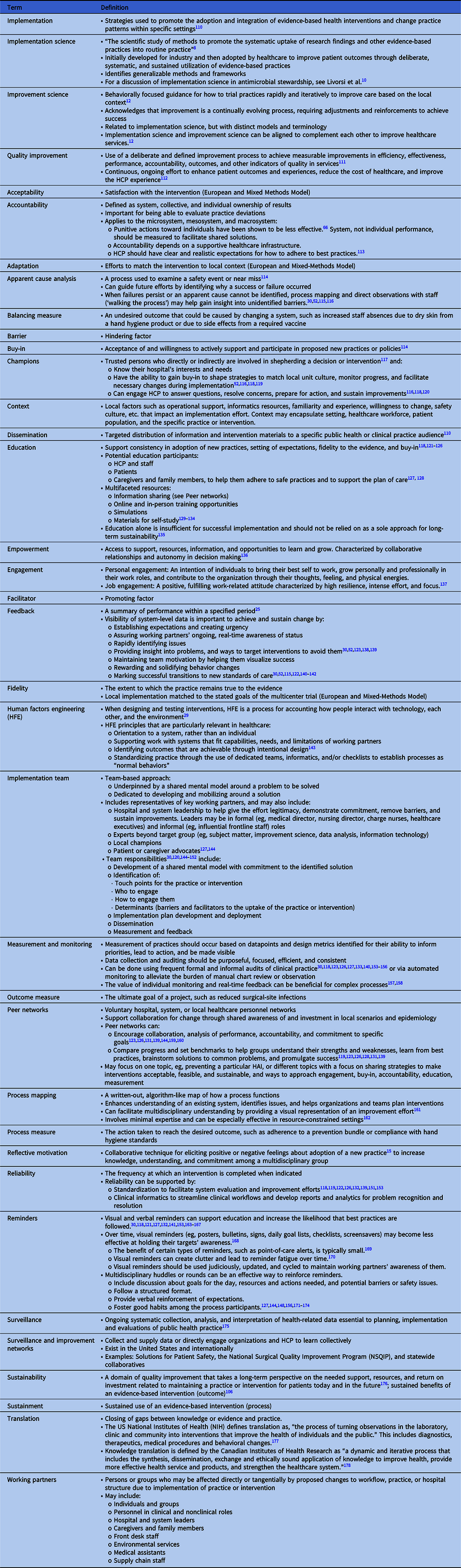

Facilitators and barriers affect implementation to differing degrees. For example, an individual practitioner may oppose a change (ie, be a barrier), but the supervisor may be able to facilitate to overcome the opposition. Alternatively, a practitioner may champion a change, but without the support of the leadership, they may be unable to initiate it. Additional influential factors include context, level of engagement, and reliability (see Table 1 for a glossary of terms).

Table 1. Glossary of Terms

Failure by HCP to adhere to a guideline or standard is a common basis for initiating an improvement project. The Cabana Framework Reference Cabana, Rand and Powe19 is a useful tool to understand how addressing real or perceived barriers can make an implementation effort successful. The framework employs 3 domains (ie, knowledge, attitude, and behavior) to understand the spectrum of barriers. The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) Reference Powell, Waltz and Chinman20 is another resource to help map barriers to strategies and identify appropriate implementation models or frameworks.

Measurement

Data are essential for implementation to establish baselines, identify opportunities, measure progress, and justify use of resources to organizational leaders. No single method or measure will work for all situations, and standardized measures often are not available. Different frameworks lend themselves to specific methodologies, but any chosen method must do the following:

-

Be appropriate for the question(s) it seeks to answer.

-

Adhere to the method’s rules for data collection and analysis. As with any project, it may be prudent to review the analytic plan with an expert to ensure that data collected will yield a result.

Choosing measures

There are 3 general types of measures employed in implementation 21 :

-

1. Outcome measure: The ultimate goal of a project, such as reduced surgical site infections or improving antimicrobial susceptibility patterns.

-

2. Process measure: The action taken to reach the desired outcome, such as adherence to a prevention bundle or compliance with hand hygiene standards.

-

3. Balancing measure: An undesired outcome that could be caused by changing a system, such as increased staff absences due to dry skin from a hand hygiene product or due to side effects from a required vaccine.

Ideally, all 3 types of measures are included in a project. For example, a project seeking to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP, ie, outcome) seeks to increase early extubation (ie, process) but needs to ensure a rise in reintubations or unplanned intubations is not occurring (ie, balancing). At times, a balancing measure may be difficult to identify due to the rarity of an event or an indirect relationship between outcome or process and balancing measures. In the VAP example, using the rate of nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP) could help identify patients who develop NV-HAP following extubation (implying they were extubated too early), but not every patient with NV-HAP will have been intubated prior to diagnosis.

Similarly, choosing an outcome measure may be difficult if the likelihood of an outcome is multifactorial or exceedingly rare. In the case of hand hygiene, improved adherence (process) should prevent nosocomial transmission (outcome). However, an overall HAI rate may not reflect the change because hand hygiene is one of many potential factors that affect nosocomial transmission. Also, it may not be possible to count all prevented transmissions. For example, a patient would not be counted if they experienced onset of an upper respiratory infection following discharge but did not require readmission. In the case of antimicrobial resistance, improved contact precaution adherence for multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) patients (ie, process) and improved antimicrobial stewardship (ie, process) should decrease morbidity and mortality due to antimicrobial resistance (ie, outcome) but may be difficult to demonstrate in a single center or short period. Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger10 In these examples, the focus of the project might be the process and balancing measures, with attention to but not reliance on the outcome.

Often, measures that are standardized and utilized broadly are referred to as ‘benchmarks.’ Measures also may be developed locally and used in a combination with benchmark measures. For instance, a facility may start with NHSN event definitions 22 and adapt them as definitions change over time or as needed based on the suitability to their setting (eg, pediatric, long-term care, home healthcare). Reference Advani, Murray, Murdzek, Aniskiewicz and Bizzarro23 As another example, facilities typically use the WHO 5 Moments process measures to identify occasions when HCP should perform hand hygiene during patient care, but the methods of measurement of adherence can vary. A facility may measure adherence to all moments, adherence to a specific moment, or the amount of hand hygiene product used. 24 When possible, it is important to use the least resource-intensive means of data collection because resources are needed to feed data back to those who were monitored. Monitoring in combination with feedback has been shown to influence change and be more effective when delivered at a high frequency. Reference Jamtvedt, Young, Kristoffersen, O’Brien and Oxman25

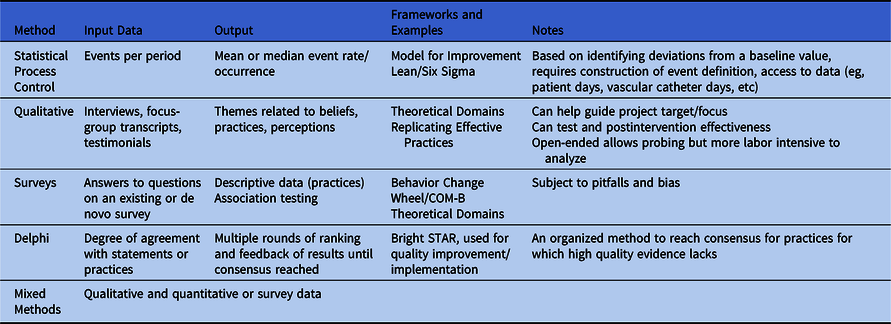

Choosing a method

Table 2 provides a nonexhaustive list of methodologies commonly used for implementation measurement. For a research-focused overview, readers are encouraged to review the 2016 SHEA series on research methods in healthcare epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship Reference Morgan, Safdar, Milstone and Anderson26 and Livorsi et al. Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger10

Table 2. Methods for Measurement

Conceptual models and frameworks

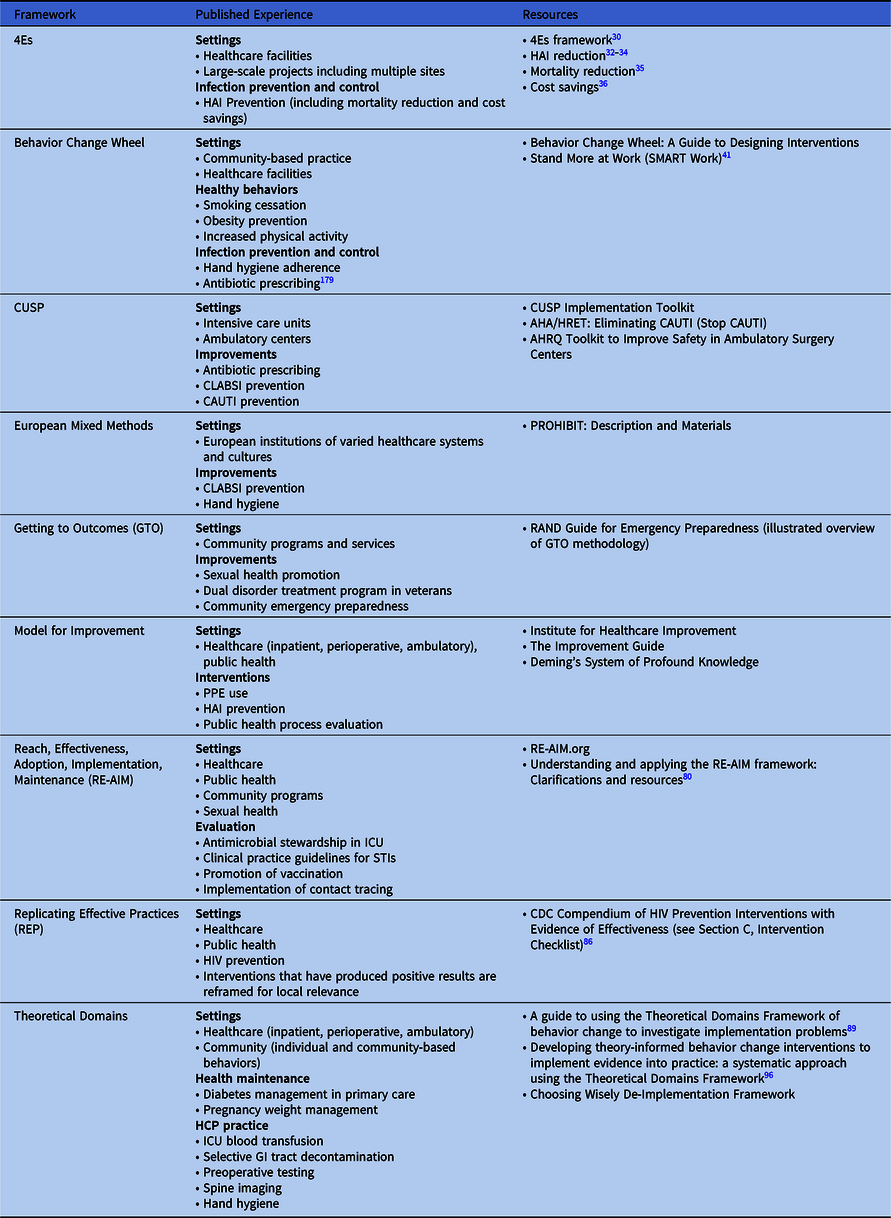

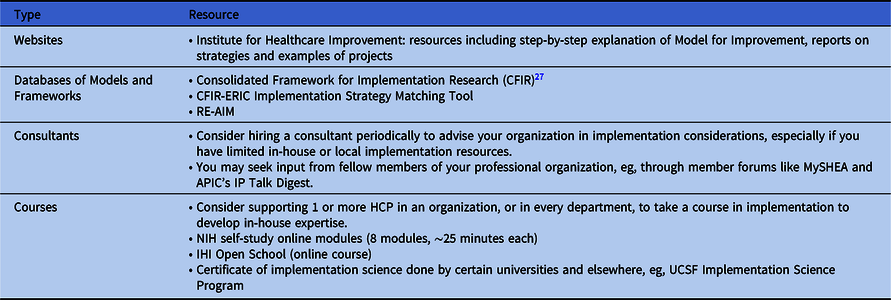

The choice of implementation methods or frameworks for any given initiative relies on the context, local knowledge and experience with implementation science, and the resources available to support the effort. Numerous frameworks combine implementation principles and tools to help organizations facilitate sustainable improvements (see Table 3 for published uses and associated resources for the models and frameworks described in this document). An organization may utilize a particular implementation framework for its relevance to a specific intervention, setting, and/or need, and another for a different initiative. As a starting point when choosing a framework, an organization may review published evidence to understand what and how framework(s) were used successfully and compare them to their local context. The following additional tools can help guide selection of framework(s):

-

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which provides a repository of constructs that have been associated with effective implementation 27

-

The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) process Reference Powell, Waltz and Chinman20 (see Table 4 for additional resources).

Table 3. Implementation Frameworks

Table 4. Other Resources

Frameworks may be combined or used on their own and are meant to help guide improvements through a systematic approach derived from behavioral and organizational science and research. Damschroder et al Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery28 describe using CFIR to guide formative evaluations and build the implementation knowledge base across multiple studies and settings, distinguishing between descriptive implementation models and action-oriented ones.

The following models and frameworks are used in healthcare, share purposeful experimentation and evaluation to achieve sustainable change, Reference Pennathur and Herwaldt29 and illustrate the variety of ways organizations may approach a problem. These models and frameworks are listed alphabetically.

The 4 “Es”

Pronovost et al articulated the 4 Es (Engage, Educate, Execute, and Evaluate), which may be the most pervasive model used in US healthcare epidemiology. Reference Pronovost, Berenholtz and Needham30 This model is well suited for large-scale projects that include multiple sites. Its cyclical nature allows for formative work and feedback to drive modifications and adaptations, and it provides a guide for resolving knowledge gaps through education. However, it does not include targeted strategies to address multilevel barriers that hinder putting knowledge into practice.

The following 4 E strategies guide organizational change efforts:

-

1. Engagement: To motivate key working partners to take ownership and support the proposed interventions.

-

2. Education: To ensure key working partners understand why the proposed interventions are important.

-

3. Execution: To embed the intervention into standardized care processes.

-

4. Evaluation: To understand whether the intervention is successful.

The 4Es guide improvement teams in planning to address key partners for the implementation process: senior hospital leaders, improvement team leaders, and frontline staff. Planning for and utilization of multifaceted interventions that address the 4Es, coupled with explicit efforts to improve teamwork and safety culture, Reference Sexton, Berenholtz and Goeschel31 have been associated with reductions in HAIs Reference Berenholtz, Lubomski and Weeks32–Reference Pronovost, Watson, Goeschel, Hyzy and Berenholtz34 and mortality Reference Lipitz-Snyderman, Steinwachs, Needham, Colantuoni, Morlock and Pronovost35 and increased cost savings. Reference Waters, Korn and Colantuoni36

Behavior Change Wheel

The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) is the result of an effort to link interventions with targeted behaviors more directly. It was developed by Michie et al, Reference Michie, van Stralen and West37 who evaluated 19 existing behavior change frameworks for comprehensiveness (ie, applicability to any intervention), coherence, and link to a behavioral model. The result was a 3-layered tool:

-

1. A behavior system composed of capability, opportunity, and motivation (COM-B)

-

2. Nine intervention functions that can be used to affect behavioral change

-

3. Seven policy categories that enable or support interventions to enact the desired behavior change.

One strength of the model is its nonlinearity, meaning that >1 behavioral system component, intervention function, and policy category can apply to an effort to affect change. Additionally, the model attempts to incorporate contextual influences on behavior, which the authors refer to as ‘automatic’ functions such as emotions and impulses that arise from associative learning and/or innate dispositions, as opposed to more reflective processes involving evaluations and plans. The BCW has been used widely in health promotion efforts such as smoking cessation Reference Gould, Bar-Zeev and Bovill38 and obesity and sedentary behavior reduction, Reference Ojo, Bailey, Brierley, Hewson and Chater39–Reference Munir, Biddle and Davies41 and COM-B has been used to investigate hand hygiene adherence Reference Schmidtke and Drinkwater42,Reference Lambe, Lydon and Madden43 and antibiotic prescribing. Reference Tomsic, Ebadi and Gosse44,Reference Courtenay, Rowbotham, Lim, Peters, Yates and Chater45

Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP)

CUSP focuses broadly on the idea of safety culture by empowering HCP to take responsibility for safety in their area, rather than defining specific domains of impact. As described by Pronovost et al Reference Pronovost, Weast and Rosenstein46 at Johns Hopkins, who developed and validated the CUSP model in intensive care settings in 2005, the program is composed of 8 steps:

-

1. Culture of safety assessment

-

2. Sciences of safety education

-

3. Staff identification of safety concerns

-

4. Senior executive adoption of a unit

-

5. Improvements implemented from safety concerns

-

6. Documentation and analysis of efforts

-

7. Sharing of results

-

8. Culture reassessment.

The US Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ), the federal agency that provided funding for the development of CUSP, maintains an updated version of this framework on its website. Reference Pronovost, Needham and Berenholtz33,47 The AHRQ also funded “On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI,” a national program to reduce the incidence of CAUTI through technical and hospital culture adaptations rooted in the CUSP model. 48 This program focused on culture change. Reference Meddings, Chopra and Saint49 CUSP has also been used in the ambulatory setting, specifically in the AHRQ “Safety Program for Improving Antibiotic Use,” a program derived from CUSP model concepts, designed to reduce overprescribing of antibiotics in primary care. Reference Keller, Caballero and Tamma50 The AHRQ has further extended CUSP into ambulatory surgery, providing a full toolkit for the prevention of surgical-site infection on their website. 51 Investigators and implementation scientists have continued to use the CUSP approach in a variety of clinical settings with mixed results. Although CUSP has shown success in preventing HAIs, such as CLABSI in US intensive care units Reference Berenholtz, Lubomski and Weeks32,Reference Miller, Briody and Casey52 and CAUTI on medical-surgical floors in acute-care hospitals Reference Saint, Greene and Krein53 and in nursing homes, Reference Mody, Greene and Meddings54 not all interventions using a CUSP-based approach have been successful. 55

European and Mixed Methods

The European and Mixed-Methods framework derives from the CFIR 27 and originated as the ‘InDepth’ work package, Reference Sax, Clack and Touveneau56 a longitudinal qualitative comparative case study within the Prevention of Hospital Infections by Intervention and Training (PROHIBIT) study. Reference van der Kooi, Sax and Pittet57,Reference van der Kooi, Sax and Grundmann58 Specifically, InDepth sought to identify the role contextual factors play in barriers and facilitators to successful implementation. Reference Clack, Zingg and Saint59 The framework defines 3 qualitative measures of implementation success:

-

1. Acceptability: Satisfaction with the intervention.

-

2. Intervention fidelity: Local implementation matched with the stated goals of the multicenter trial.

-

3. Adaptation: Local efforts to match the intervention with local context.

The framework has not been applied beyond the PROHIBIT outcomes of CLABSI rates and hand hygiene adherence, Reference van der Kooi, Sax and Pittet57,Reference van der Kooi, Sax and Grundmann58 but the reported results may be used to inform other approaches.

Getting to Outcomes (GTO)®

Getting to Outcomes (GTO)® is a means of planning, implementing, and evaluating programs and initiatives developed for community settings. GTO® seeks to build capacity for self-efficacy, attitudes, and behaviors to yield effective prevention practices. Reference Chinman, Hunter and Ebener60 The process involves 10 steps:

-

Steps 1–5: Assess and evaluate needs, goals, and feasibility of a proposed program.

-

Step 6: Plan and deliver the program.

-

Steps 7–10: Evaluate, improve, and sustain successes.

GTO® has been utilized for numerous community-based initiatives, such as evidence-based sexual health promotion, Reference Chinman, Acosta, Ebener, Malone and Slaughter61 a dual-disorder treatment program for veterans, Reference Chinman, McCarthy, Hannah, Byrne and Smelson62 and development of casework models for child welfare services. Reference Barbee, Antle, Wandersman and Cahn63 Additionally, the RAND Corporation has published a guide to develop community emergency preparedness programs. This guide breaks down each of the 10 GTO® steps, provides materials and examples, Reference Ebener, Hunter, Adams, Eisenman, Acosta and Chinman64 and may facilitate the use of GTO® in implementing infection prevention interventions.

Model for Improvement

The Model for Improvement Reference Langley, Moen, Nolan, Nolan, Norman and Provost65 was developed by the Associates for Process Improvement based on Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge. Reference Deming66 It has since been adopted widely, perhaps most notably by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in its 100,000 and 5 Million Lives campaigns of the early 2000s. 67 The model has been used to accelerate change in a variety of healthcare and public health settings, Reference Lannon and Peterson68–Reference Harrison, Shook, Harris, Lea, Cornett and Randolph70 and subspecialists have created primers focused on their practice areas. Reference Guo, Fortin, Mayo, Robinson and Lo71–Reference Gaudreault-Tremblay, McQuillan, Parekh and Noone74 The Model for Improvement begins with 3 questions:

-

1. What are we trying to accomplish?

-

2. How will we know that a change is an improvement?

-

3. What change can we make that will result in improvement?

Once those questions are answered, the identified changes or interventions are tested using plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycles. Individual tests include the following:

-

Plan: Predictions of outcome.

-

Do: Executed according to plan.

-

Study: Analysis and evaluation.

-

Act: Decision whether to keep, abandon, or modify the intervention.

PDSA findings and decisions then guide planning the next experiment, starting a new PDSA cycle. Multiple cycles are done in series called ‘ramps.’ The Model for Improvement is designed for team-driven projects, relies heavily on data analysis and interpretation, and requires training (much of which can be self-directed online).

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM)

Reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance make up the 5 dimensions of the planning and evaluation framework RE-AIM, developed to address the failures and delays in translating scientific evidence into policy and practice. Reference Nhim, Gruss and Porterfield75,Reference Glasgow and Estabrooks76 By utilizing these 5 dimensions at individual and ecological levels, teams can better understand the effectiveness of programs as they are implemented in real-world community settings. Reference Trivedi, Lewis and Deloney77,Reference Glasgow, Vogt and Boles78

RE-AIM is useful for planning an intervention, the outcomes that will be measured, and evaluating whether the intervention has met its goals. Reference Smith and Harden79 All 5 dimensions are not always addressed. In recent years there has been greater emphasis on pragmatic application of the framework to determine which dimensions an organization should prioritize. Reference Holtrop, Estabrooks and Gaglio80 It also provides ideas for quantitative measurements of outcomes.

RE-AIM was utilized to evaluate an antimicrobial stewardship program in an ICU in South Africa, Reference Nkosi and Sibanda81 dissemination and implementation of clinical practice guidelines for sexually transmitted infections, Reference Jeong, Jo, Oh and Oh82 and promotion of vaccination via digital technology. Reference Stephens, Wynn and Stockwell83 Recently, to better understand the implementation of contact tracing for emerging infectious diseases, RE-AIM was used to evaluate individual and systems-level predictors of success of an emergency volunteer COVID-19 contact tracing program in Connecticut. Reference Glasgow and Estabrooks76,Reference Glasgow, Vogt and Boles78,Reference Shelby, Schenck and Weeks84 Investigators concluded that the program fell short of CDC benchmarks for time and yield, largely due to difficulty collecting the information necessary for outreach.

Replicating Effective Practices (REP)

The Replicating Effective Programs (REP) framework may be used to balance needs of the target population with the core elements of successfully implemented interventions 85 and to maximize fidelity to core interventions that have been rigorously tested and have produced statistically significant positive results. 86

There are 4 phases of REP Reference Kilbourne, Neumann, Pincus, Bauer and Stall87 :

-

1. Preconditions (ie, identification of needs)

-

2. Preimplementation (eg, community input)

-

3. Implementation (eg, training)

-

4. Maintenance (eg, preparing for sustainability).

REP may be useful when adapting interventions for a specified target audience within healthcare. It also may be applied across the continuum of care (eg, acute care to long-term care) or in multifacility systems when local institutional culture dictate the need for adaptation. When used to disseminate evidence-based HIV prevention interventions to community-based organizations, the application of REP to packaging, HCP training, and technical assistance resulted in more effective uptake than dissemination alone. Reference Kilbourne, Glasgow and Chambers88

Theoretical domains

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was initially developed to conduct research on the behavior of HCP as it relates to implementing evidence-based practices. Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam89 The initial organization of TDF Reference Michie, Johnston and Abraham90 was modified following a formal validation exercise, Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie91 which yielded 14 domains to identify relevant cognitive, affective, social, and environmental influences on behavior. Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam89 TDF has been used widely to understand and influence HCP, Reference Squires, Linklater and Grimshaw92 patient, and population behaviors, most commonly with qualitative methods (eg, surveys, interviews, and/or focus groups). Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam89 One salient example is a patient safety effort to properly place nasogastric tubes. A team utilized a validated TDF-based questionnaire to identify relevant domains that were then explored in focus groups to help connect theory to techniques to change behavior. Reference Taylor, Lawton, Slater and Foy93 More recently, TDF was used to develop the Choosing Wisely De-Implementation Framework Reference Grimshaw, Patey and Kirkham94 that proposes to reduce low-value care, defined as a test or treatment for which there is no evidence of patient benefit or where there is evidence of more harm than benefit. Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou and Doust95 A guide to TDF use Reference Atkins, Francis and Islam89 and a 4-step systematic approach to using TDF Reference French, Green and O’Connor96 were published to help teams design and follow through with an intervention. TDF has been linked to the COM-B model (used in the aforementioned BCW) and has been used in combination with other frameworks when the time necessary to complete interviews and focus groups was limited. Reference Atkins, Hunkeler and Jensen97

Future needs

Models for underperforming hospitals and units

Allthough national implementation studies have succeeded in preventing several different HAIs, investigators have not seen the same success when focused on facilities most in need of help—hospitals underperforming with respect to HAI prevention. The CDC-funded national prospective, interventional, quality improvement program, CDC STRIVE (States Targeting Reduction in Infections Via Engagement), focused on reducing CLABSIs, CAUTIs, Clostridioides difficile infections, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections in hospitals with a disproportionately high burden of HAIs. Reference Popovich, Calfee and Patel98 Although nearly 400 US hospitals participated in this multimodal, multifaceted, partner-facilitated program, they did not see significantly reduced rates of CLABSI, Reference Patel, Greene and Jones99 CAUTI, Reference Meddings, Manojlovich and Ameling100 C difficile infection, Reference Dubberke, Rohde and Saint101 or MRSA bloodstream infection. Reference Calfee, Davila and Chopra102 More recently, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) funded a national program that invited US hospitals that had at least 1 adult ICU with elevated CLABSI or CAUTI rates to participate in an externally facilitated program implemented by a national project team and state hospital associations using the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) framework. Reference Meddings, Greene and Ratz103 Results from the first 2 cohorts (366 recruited ICUs from 220 hospitals in 16 states and Puerto Rico) revealed no statistically significant reductions in CLABSI, CAUTI, or catheter utilization in the 280 ICUs that completed the program. Reference Meddings, Greene and Ratz103 These researchers cite a number of possible factors contributing to the disappointing result, including underutilization of training and coaching resources, lack of infrastructure, and a different selection process for participants (eg, identifying low-performing units or those that had been unsuccessful to date versus asking for volunteers for earlier CUSP work, which may have selected for early adopters and high performers). Investigations in this and similar cohorts could help elucidate why hospitals with disproportionately high HAI rates have not yet seen significant reductions in HAIs despite broad-based efforts. Increased focus on the development, adaptation, and utilization of implementation models and frameworks to infection prevention and control may help identify implementation gaps that contribute to lack of improvement and guide their closure.

Sustaining system change

A long-term goal of any implementation effort is to sustain and advance short-term gains. Ideally, sustaining gains occurs with less intensity than initial efforts, maintaining gains or improving at a slower rate and allowing resources to be directed to another effort. Characteristics of successfully sustained interventions have included those that are incorporated into the standard workflow, have effective champions to shepherd the effort and re-engage when necessary, can be modified over time, fit with an organization’s mission and procedures, provide easily perceived benefits to staff members and/or clients, and are supported by partner organizations. Reference Scheirer104 It can be difficult to meet those criteria in healthcare, where changes in workflows and staff are frequent. Reference Fowler, Krein, Ratz, Zawol and Saint105 Demonstrating successfully sustained implementation should include evidence of (1) sustainment, that is, sustained use of an evidence-based intervention (process measure), and (2) sustainability, that is, sustained benefits of an evidence-based intervention (outcome measure). Reference Moullin, Sklar and Green106

Linking ongoing process data to ongoing outcome data can prove challenging. In one study, CLABSI reduction in ICUs was sustained for a decade, but process measurement was not performed. Reference Pronovost, Watson, Goeschel, Hyzy and Berenholtz34 A study on CAUTI prevention at a Veterans’ Affairs (VA) hospital found that, 8 years after implementation, appropriateness of urinary catheters remained high and stable. Reference Fowler, Krein, Ratz, Zawol and Saint105 Catheter use decreased, but the facility was unable to report outcome data. Reference Fowler, Krein, Ratz, Zawol and Saint105 These researchers hypothesized that success was due to a 3-component, evidence-based intervention, institutionalization of the interventions (ie, standardizing nursing assessments and handoffs that included the intervention), and effective champions who re-engaged when necessary. Additionally, a study on hand hygiene on 2 hospital units in Italy found that adherence dropped after 4 years (from 84.2% to 71%) despite maintaining champions and processes. Reference Lieber, Mantengoli and Saint107 Recent proposals for standard definitions Reference Moullin, Sklar and Green106,Reference Moore, Mascarenhas, Bain and Straus108 and modified ERIC strategies to account for sustainment and identify interventions that yield short-term and sustained improvements Reference Nathan, Powell and Shelton109 can form a basis for future research and understanding.

Conclusion

It is increasingly evident that implementation is essential to ensuring that evidence-based interventions are performed to generate desired outcomes and to meet infection prevention and control and antimicrobial stewardship goals. Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger10 Furthermore, a detailed implementation plan in a specific healthcare setting for a given intervention is necessary for success, as the implementation approach in one facility may not be reproducible, with the desired effect, in another. In this article we have provided an overview of implementation in a general sense, with a glossary of terms, broader discussion of key methods, models, and frameworks, possible future areas of study, as well as links to resources readers can use to initiate or continue their implementation journey.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2023.103

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cara C. Lewis, PhD, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA and Lynn Hadaway, MEd, RN, Lynn Hadaway Associates Inc (Milner, GA) for their contributions to SHEA’s efforts to advance infection prevention and healthcare epidemiology through implementation science, and for the contributions of their subject matter expertise to this article.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support

SHEA funded the development and publication of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The following disclosures reflect what has been reported to SHEA. To provide thorough transparency, SHEA requires full disclosure of all relationships, regardless of relevancy to the guideline topic. Such relationships as potential conflicts of interest are evaluated in a review process that includes assessment by the SHEA Conflict of Interest Committee and may include the Board of Trustees and Editor of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. The assessment of disclosed relationships for possible conflicts of interest has been based on the relative weight of the financial relationship (ie, monetary amount) and the relevance of the relationship (ie, the degree to which an association might reasonably be interpreted by an independent observer as related to the topic or recommendation of consideration). K.K.T. is the owner of the consulting company Trivedi Consults. V.M.D. is the owner of the consulting company Youngtree Communications. R.C. has consulting relationships with Moderna, Novavax, and Pfizer (speakers bureau, research contract) and Sanofi (speakers bureau). M.L.S. has grant funding from 3M and PDI for nasal decolonization. All other authors report no conflicts of interest related to this article.