Will the outbreak of COVID-19 mark a sea change in countries’ approaches to surveillance, civil liberties, and policies at the intersection of public health and public security? If so, how will these changes affect governance in democratic and authoritarian political systems worldwide, and what international standards and norms will emerge?

Less than a year into the pandemic, COVID-19 has already reshaped many governments’ approaches to health surveillance, the privacy of health data, and the use of technological monitoring tools to enforce policies aimed at the preservation and protection of public health, safety, and social stability. Its impact includes the United States: according to one survey, by April 2020 a majority of Americans viewed infectious disease as a greater threat to the United States than terrorism, nuclear weapons proliferation, or the rise of China,Footnote 1 sparking calls to treat health security as a more urgent priority alongside more conventional security threats. Indeed, 2020 has seen global debate over whether the pandemic will be an inflection point in world politics or whether international relations will largely return to business as usual.Footnote 2 One important aspect of this debate is how much the pandemic is likely to change patterns of liberal and illiberal governance, and the global balance of democracy and dictatorship.

In the months following the outbreak in Wuhan, more than eighty countries adopted emergency policies to address the coronavirus, with widely varying effects on citizen liberties and political participation.Footnote 3 Some countries instituted strict lockdowns, confining citizens to their homes or sharply limiting assembly and travel. Others adopted fewer of these restrictions, but employed intensive monitoring and “test and trace” approaches. Still others pursued combinations of the two approaches. And although democracies have, on average, been less likely to violate democratic standards and infringe upon citizen rights, their responses have been heterogeneous: some have expanded executive emergency powers, some have delayed elections, and some have employed intensive monitoring. Policy responses from hybrid regimes and non-democracies produce an even wider variety of reactions. Cumulatively, these variations reinforce the need to examine how the pandemic might impact global liberalism and democracy.

Because the pandemic started in China—the world's largest autocracy—the People's Republic of China (PRC) has had a head start in crafting its model of pandemic response and promoting that model around the world, meaning that the first-mover role is held by an autocracy. It is also a decidedly illiberal autocracy that was—prior to the coronavirus outbreak—already actively pursuing a techno-surveillance state of remarkable ambition at home, exporting those technologies around the world, and pursuing a position of nascent dominance in global standard-setting and regulation of emerging surveillance technologies.Footnote 4 Pre-existing concern about these steps in the PRC, combined with the expanded use of surveillance as a global component of pandemic response, and Beijing's willingness to advertise itself as a model of pandemic response for other countries have raised alarms among policymakers and pundits about the future of civil liberties and democracy.Footnote 5

This article suggests that some of these concerns are warranted. China's position in the international system makes it more likely that illiberal approaches to governance will spread, and the pandemic has contributed to violations of democratic standards and human rights in a number of countries. Conversely, however, other factors in the international system—such as the fact that many aspects of China's governance structure are not replicated elsewhere—will likely act to limit the transferability and diffusion of China's model. Moreover, it is important to note that surveillance is not synonymous with autocracy: where surveillance has been employed but subjected to rule of law and liberal institutions, its impact on democracy has been relatively limited. The pandemic's impact, therefore, is likely to be cross-cutting and multifaceted, and patterns of change in liberal versus illiberal politics may not be as cleanly aligned with changes to global democracy and autocracy as one might initially think.Footnote 6

This article proceeds in five sections. I first trace the development of the “prevention and control” model that China has employed in response to COVID -19, showing that it relies heavily on an interweaving of public health with authoritarian tools of surveillance, policing, and securitization. Second, I review what scholarship on international diffusion predicts for the spread of China's model, showing that it identifies both prospective patterns and significant limits on any potential diffusion process. In the third section I examine the pandemic's initial effect on democracy, showing that it has primarily accelerated existing trends; that threats to democratic erosion often come from mechanisms other than surveillance; and that consolidated democracies have experienced relatively minimal levels of democratic violation, while risks are greater in autocracies and weakly democratic or hybrid regimes. In the fourth section I analyze the use of surveillance in democracies to further probe the distinction between liberalism and democracy. I show that democratic societies have used heterogenous technological solutions, but where they have adhered to principles of proportionality, temporal and scope limitation, and democratic review, the effect has been democracy-protective: norms, institutions, and public opinion have all worked in tandem to insulate democracies from pandemic-related erosion. I conclude with reflections on policy and suggestions for future research.

China's Illiberal Model: Fusing Public Health, Surveillance, and Security

As the epicenter of the outbreak, China provided the first model of pandemic response for COVID-19, and one that was explicitly illiberal and autocratic. Public health, surveillance, and state police power have been intertwined from the first days of the crisis.Footnote 7 The Chinese term for the PRC's approach to the coronavirus is “prevention and control” (fangkong, 防控), a term that appears in the full name of the Chinese CDC, was used in previous infectious disease outbreaks,Footnote 8 and has been used frequently by Xi Jinping and other senior leaders to describe China's approach.Footnote 9

As a concept, however, fangkong actually originated from the realm of policing and social stability maintenance. PRC Minister of Public Security Tao Siju, among others, used the term to refer to internal security in the mid-1990s, and it became increasingly common in the early 2000s, as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership pursued “prevention and control systems” to manage fast-moving, networked threats in Chinese society. One 2020 article retroactively linked fangkong to Xi Jinping's experience with SARS in Zhejiang, describing how Xi's effective management of provincial prevention and control efforts prompted him to “think more deeply about non-traditional security.”Footnote 10 Under Xi Jinping's leadership, fangkong has emerged as a central concept in the CCP's approach to social control and regime security, a shift away from the Hu-Wen discourse of “stability maintenance” (weiwen) that Xi-era leaders perceived as too reactive and compared to treating symptoms rather than addressing underlying causes. Today, Chinese leaders describe a vision of a “three-dimensional, information-based system of prevention and control for public security.”Footnote 11 Xi Jinping's call in May 2020 for early warning systems and timely and accurate monitoring in public health directly paralleled previous calls for bolstering those capacities in China's public security intelligence apparatus, which monitors society with the goal of preventing instability and social unrest.

This discursive overlap signals the ways China's illiberal authoritarian approach to governance was employed in pandemic response. With the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in Wuhan in late 2019, a surveillance and social control system that had been overhauled and strengthened by Xi Jinping since 2013 swung into action.Footnote 12 Public security officials worked with private technology companies like Alibaba and Tencent to develop a health code app that gathered data on individuals’ movements, contacts, and biometric data such as body temperature.Footnote 13 That information was used to generate color codes that determined citizens’ access to public spaces and ability to move; it was also shared with police and other local authorities, who merged it with existing databases and mobilized thousands of personnel at the grassroots level to enforce local lockdowns.Footnote 14 The Central National Security Commission, China's top national security body, met in April 2020—only its third meeting since the body was established—to discuss how best to monitor the pandemic's impact on internal stability.Footnote 15 By the late spring of 2020, the Ministry of Public Security openly framed COVID-19 as not only a “test of China's governance system,” but as a test of the public security organs themselves, affirming their central (and in this rhetoric, successful) role in implementing prevention and control.Footnote 16 Subnational jurisdictions of China have since proposed making permanent some tools used to combat coronavirus, such as health tracking via smartphone.Footnote 17 Technological surveillance, therefore, has merged public health into China's existing architecture of social control: it has allowed citizens to regain mobility and resume daily activities, but at the cost of embedding them further into the CCP's intensive and open-ended surveillance regime.Footnote 18

Other dynamics that emerged in China's response are also characteristics associated with illiberal governance (and to a lesser extent, the lack of competitive electoral processes in China's single-party regime). Local unwillingness to communicate information upwards in a transparent fashion slowed down China's response both domestically and in terms of its communication with the WHO and international community, as did the coercive silencing of whistleblowers.Footnote 19 Although the CCP replaced some low- and mid-level officials it said had mishandled the initial response (the most senior of whom were the party secretaries in the city of Wuhan and Hubei province), it has not publicly investigated or held accountable any of China's central leadership, and is unlikely to do so absent a system of checks and balances that often produces high-level scrutiny in democracies.Footnote 20 Finally, the melding of public health and public security does not just securitize public health, but also medicalizes public security in ways that have been used in China to justify intensely intrusive and repressive policies—most notably, likening collective detention and forced re-education camps in Xinjiang to “political immunization” against disloyalty.Footnote 21

The PRC has developed a model of pandemic response, therefore, which envisions a significant role for state surveillance and is deeply entwined with China's own illiberal governance. Many of the basic features of that model pre-dated the pandemic, but some of its key characteristics have been enhanced and potentially legitimated by China's coronavirus experience.

Will China's Model Diffuse Abroad? Lessons from IR Theory

The CCP has not just developed a model of pandemic response: it has been willing to spread that model, and in some cases has actively facilitated its adoption abroad. The regime has promoted its approach to coronavirus management using tools ranging from government-to-government outreach and export of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)Footnote 22 to foreign aidFootnote 23 to propaganda and disinformation.Footnote 24 These tools serve a number of purposes: they help to control global narratives about spread and management of the virus, they deflect blame over its origins and early transmission, and they promote positive images of China's leadership role in pandemic response. The State Council's June 2020 White Paper, for example, explicitly argues that China is “sharing its experience for the world to defeat the global pandemic.” The announcement particularly lauds the effectiveness of the “tight prevention and control system involving all sectors of society,” which it credits with enabling China to “win its all-out people's war against the coronavirus.”Footnote 25

But will China's model in fact spread and be adopted worldwide? If so, how and where? Much of the writing in the early months of the pandemic warned that coronavirus could usher in an expansion of digital surveillance.Footnote 26 Applying insights from what we already know about diffusion processes in global politics, however, suggests that diffusion is not a foregone conclusion, and that any diffusion that might occur will almost certainly not be uniform. Instead, it is likely to vary according to geographic proximity to China, regime type and sub-type, and levels of pre-existing interaction or partnership with the PRC.Footnote 27 Countries that already have close ties to China and share a similar regime type are theoretically more likely to adopt features of Beijing's approach.

Some of what we have observed in global pandemic response is clustering rather than diffusion: countries that experience a common exogenous shock (pandemic onset) have adopted similar policy responses simply because they have similar resources to confront similar public health challenges. Typically, political scientists have distinguished clustering—similarity of response across independent observations due to similar underlying conditions—from diffusion, which involves interdependent observations and argues that the occurrence of some event or policy innovation in Country A (in this case a particular pandemic response in China) increases the probability of a similar outcome or policy innovation in Country B (or C, D, E, etc).Footnote 28 Arguing that China's model has diffused is a step beyond simply noticing clustering of similar pandemic responses; it requires observers to identify and demonstrate how developments in or actions taken by the PRC have raised the probability of similar steps being adopted in other countries.

In the contemporary international environment, we have observed some evidence of diffusion via learning mechanisms, particularly learning that is facilitated by global epistemic communities in medicine and public health.Footnote 29 Scientists around the world have looked to colleagues in other countries to identify best practices in virus response (from social distancing to mask-wearing) and assess how to adapt these practices to local contexts. Learning has also occurred at the inter-governmental level: the United States held weekly meetings in the early months of the pandemic with counterparts in (mostly) democratic countries in Asia (India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and Vietnam), which shared information on the virus and discussed best practices in treatment as well as steps to address a “disinformation campaign that was being launched, in particular, from China.”Footnote 30 We also see some evidence of emulation, another diffusion mechanism, as successful democracies have served as models for others. Israel, for example, announced that it was modelling its approach to surveillance on that of Taiwan, and leaders of several countries called South Korean President Moon Jae-in to learn about South Korea's approach.Footnote 31

Thus far, however, the most obvious diffusion processes observed have not emanated specifically from China. Masks, for example, are widely used throughout East Asia, so the global adoption of mask-wearing cannot be credited to diffusion from China. As yet, the hallmarks of China's political response to the pandemic—intensive tech surveillance coupled with mass mobilization at the grassroots/local level to ensure short periods of near-total lockdown—are not the features of pandemic response policy that have diffused most widely.

Indeed, scholarship on global diffusion highlights not just the potential for a China-based diffusion process, but also its likely limits. Recent work, for example, demonstrates that political phenomena are more likely to diffuse to regimes that share similar features,Footnote 32 but the underlying institutions used in China's pandemic response are not especially common outside the PRC. As noted above, China had pursued intensive tech-based surveillance and securitization to an unusual degree prior to the coronavirus outbreak, and its approach to the pandemic relied not only on merging public health data into existing surveillance infrastructure, but on grassroots organization and mobilization of a kind that does not exist in many other regimes, even those with relatively permissive authoritarian conditions. Still other factors that are present to varying degrees around the world but are not features of the Chinese political system—such as federalism, partisan polarization, and tolerance for individual non-compliance—could further limit the transmissibility of China's approach.Footnote 33 This suggests that even regimes that try to emulate the PRC's response are unlikely to be able to replicate it wholesale, limiting the extent and depth of global diffusion.

Although wholesale emulation seems theoretically unlikely, other elements of China's approach could spread through market mechanisms. China's tech companies already export surveillance technologies of various types to at least eighty countries, including consolidated democracies, hybrid regimes, and full autocracies.Footnote 34 These companies already had a first-mover advantage in experimenting with, testing, and fine-tuning specific health surveillance technologies. Countries that struggle to control the coronavirus, therefore, may find themselves turning to Chinese vendors both for lack of a competitive alternative and because some of them already have supplier-client relationships with PRC-based surveillance technology companies that were established pre-pandemic. The Chinese party-state's foreign policy priorities could play a role in this kind of diffusion process, but firms’ market incentives are likely to play a role as well, meaning that the effect would be a somewhat different global pattern and distribution of China-originating surveillance technologies. Which mechanism drives any global diffusion process that occurs, and to what extent, is a promising topic for future inquiry.

China's model will also be more likely to spread if international organizations (IOs) facilitate a global environment conducive to China's model—for example, by disseminating standards that tilt the global marketplace and regulatory environment in favor of China or Chinese companies. China has already, arguably, moved from being a “norm-taker” to a “norm-maker” in this domain; it had, for some time prior to COVID, been actively shaping global norms and regulations governing the development and use of surveillance technologies.Footnote 35 On this issue, the PRC has pursued a highly strategic approach, organizing domestic actors to develop Chinese domestic standards and then actively promoting the proposed standards in international fora.Footnote 36 On the eve of the pandemic, China had already begun to outpace the US and other countries in setting global standards for emerging surveillance technologies: as of late 2019, Chinese tech companies had made the only submissions on facial recognition to the UN's International Telecommunications Union (ITU), half of which had been approved.Footnote 37 Active leadership at the ITU and other technology standard-setting bodies has helped the PRC quietly and quickly shape the global regulatory environment, and COVID has provided a further opportunity to use these bodies to highlight the effectiveness of China's approach.Footnote 38 Going forward, leadership in terms of global regulation could help maintain or increase Chinese companies’ market access; this in turn is likely to facilitate bottom-up acceptance of Chinese standards in an increasing number of countries and make it harder for the international community to sanction China for development and export of technologies used to violate human rights.Footnote 39 In that sense, China's IO engagement could facilitate development of a strand of global order that is decidedly illiberal, and market and political mechanisms of diffusion may ultimately reinforce each other in that process.Footnote 40

A final factor that will shape this discussion is the structure of the international system and the presence or absence of any potential democratic alternative that could compete with or offset diffusion originating from China. At present, though some democracies have experienced notable success in controlling the coronavirus and have shared these lessons with others, there is not a single democratic model spreading alongside Beijing's attempts to publicize the Chinese approach, and especially not one whose country of origin has the major power status of the PRC.Footnote 41 Previous literature suggests that the autocratic or democratic identity of global hegemons and major powers can affect worldwide prevalence of democracy;Footnote 42 the future structure of the international system may therefore also favor the spread of a Chinese model (with the caveats and constraints described above) unless another major power can offer an alternative.

Beyond Diffusion: Democratic Erosion and Democratic Insulation

Even if China's model of illiberal authoritarian response to COVID-19 does not diffuse, the pandemic could have negative effects on global patterns of democracy via other pathways. During the early months of 2020, media and policy analysts expressed concern that the pandemic would undermine global democracy and reinforce the powers of repressive governments worldwide.Footnote 43 They highlighted cases like China's where tools of authoritarian governance were being repurposed to enforce lockdowns, strengthening these regimes' surveillance and coercive capacity in the process.Footnote 44 In democracies and semi-democratic countries, analysts highlighted events such as the cancellation of elections (Bolivia); application of curfews, censorship, and media constraints (India); rapid expansion of surveillance (Israel); and passage of emergency decrees and expanded executive powers, some used to silence critics (Hungary, the Philippines,Footnote 45 and countries in eastern and southern Africa).Footnote 46 Domestic use of the military to enforce lockdowns (as in Central & South America) also raised the specter of civil-military dysfunction and military intervention in domestic or civilian political life.Footnote 47 Overlaying all this was the concern, based on evidence about the stickiness of emergency powers and security measures adopted under crisis in the past, that restrictions intended to be temporary would in practice be difficult to roll back or contain (a dynamic explored in more detail in David Stasavage's contribution to this special issue).Footnote 48

Civil liberties are an important component of democracy, but not its only defining attribute;Footnote 49 similarly, health surveillance encroachment on civil liberties is not the only mechanism by which the pandemic could produce democratic erosion or autocratization. Other pathways include limits on media reporting and/or censorship of information; military intervention in civilian politics; repression and abuse by police or other security forces during lockdown enforcement; and discrimination against sick individuals or particular groups as a result of pandemic politics. The pandemic could also contribute to the rise or consolidation of power by populist leaders who use moments of health and economic crisis to strengthen personal rule through manipulation of standard democratic constraints and electoral processes, or who use emergency degrees to aggrandize executive power that outlasts pandemic conditions.Footnote 50

The presence of multiple pathways that could produce democratic erosion is an important methodological challenge. Not only should these pathways be clearly identified where possible in order to better understand the precise risks the pandemic poses to global democracy, but our analysis must also take into account the fact that a number of global trends toward autocratization pre-dated the outbreak.Footnote 51 Not all autocratization in 2020 (or after) will be attributable to the pandemic. Some of the leaders and countries highlighted for problematic responses thus far—such as Orban in Hungary or Duterte in the Philippines—were not impeccably democratic beforehand: they exhibited behavior that raised concerns or even prompted changes in the classification of democracy prior to the discovery and spread of coronavirus. Other concerns that have appeared to be contemporaneous with the pandemic are, upon closer scrutiny, unrelated to it even though they occur in parallel; in South Korea, for example, weakening separation of executive and judicial branches, and crackdowns on the civil liberties of North Korean defectors for reasons to do with President Moon Jae-in's approach to inter-Korean relations, have both undermined liberal democratic norms in ways that are not pandemic-dependent.Footnote 52

Yet the pandemic may also be a reinforcing or permissive factor. It can provide justification for expansion of surveillance in a full authoritarian regime, enhancing its repressive capacity. In a hybrid regime or weak democracy, the pandemic could provide pretext for weakening media laws or distortion of civil-military relations, paving the way toward incumbent takeover.Footnote 53 In South Korea, a full democracy, already-deepening polarization has been accelerated by the Moon administration's blame of conservative churches for being major outbreak sites, providing further reason to be concerned about democratic decline.Footnote 54

These counterfactuals are tricky. Knowing which trends would have existed without the pandemic, which have been exacerbated by it, and which would not have appeared otherwise and were directly brought into being by the pandemic will be an ongoing intellectual and methodological challenge. In assessing the virus's impact on democratic corrosion, analysts must think carefully about how pre-existing and parallel-but-separate political trends should be weighted against pandemic-specific policy responses.Footnote 55

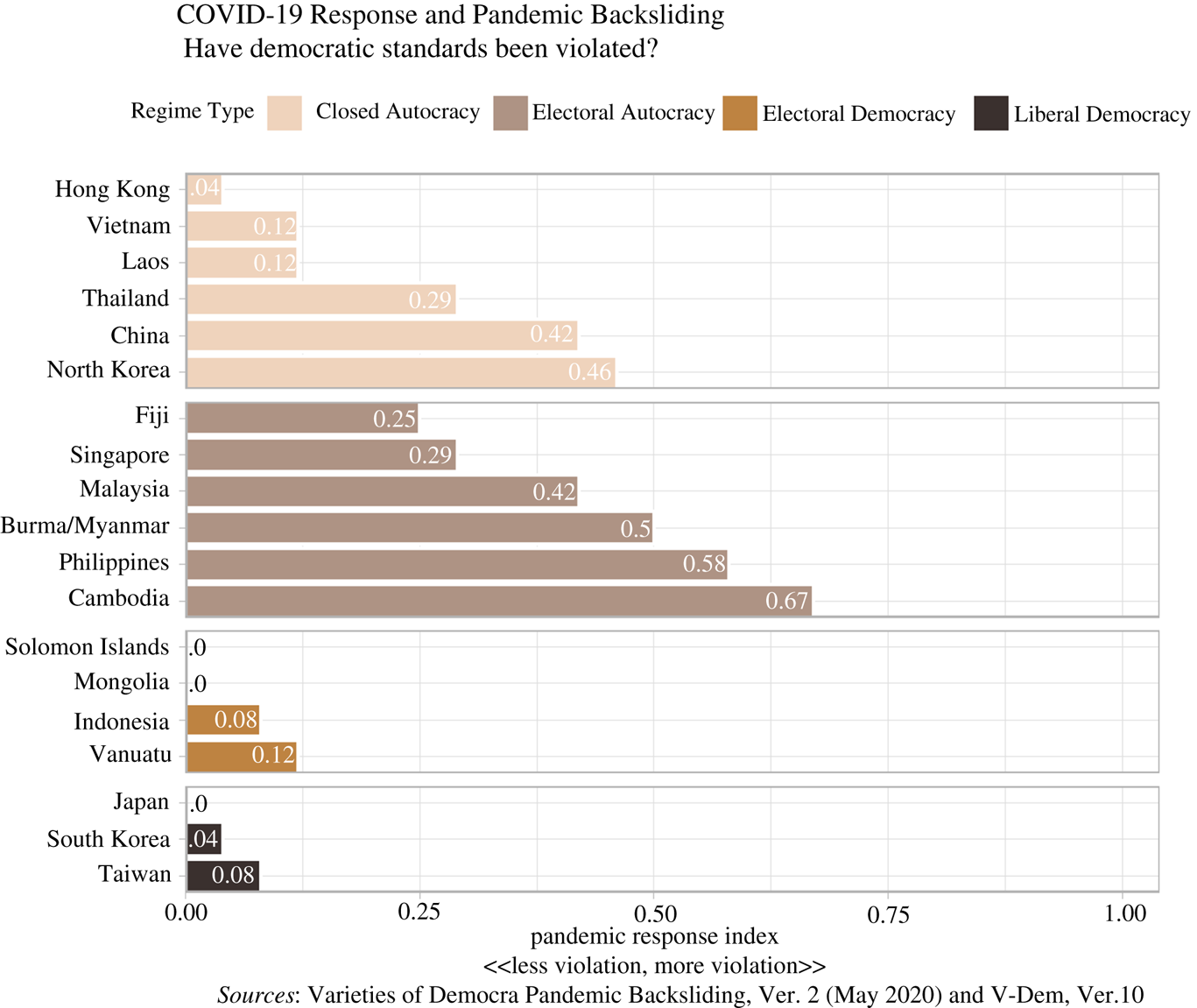

Although the outbreak raised clear concerns about democratic erosion and autocratization, cited above, reality during the first months of pandemic response has been considerably more nuanced. Early data suggests that the pandemic's main effect has been to deepen existing political trends. The Varieties of Democracy project (V-Dem) has created a Pandemic Democratic Violations Index and a Pandemic Backsliding Index, which measure “the degree to which democratic standards for emergency measures are violated by government responses to Covid-19.”Footnote 56 The project examines six major types of violations of democratic standards, including (1) emergency measures without a time limit; (2) discriminatory measures; (3) de jure violation of what the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) defines as “non-derogable” rights;Footnote 57 (4) restriction of media freedom; (5) disproportionate limits on legislative power; and (6) abusive enforcement. Although the project has identified places where weakly democratic governments appear to be using the pandemic to erode democratic institutions and civil liberties, it also finds that the most severe pandemic-related restrictions have been applied in places that are already fully autocratic; conversely, two-thirds of democracies have implemented emergency measures without significantly compromising or violating their democratic standards.Footnote 58

The region where geographically-based diffusion of a China model should be most pronounced is Asia,Footnote 59 but preliminary evidence from the region in fact suggests that geographically-driven diffusion of China's approach has either not occurred or has not undermined democracy in significant ways. Across the region, there is strong correlation between measures of liberal democracy and of pandemic response, suggesting that violations have been more severe in the regime types already prone to violations of rights—full or electoral autocracies.

FIGURE 1. COVID-19 response and pandemic backsliding in Asia by country

Source: Figure reprinted with author's permission from Denney Reference Denney2020.

Similar trends appear to have played out globally in the pandemic's first nine months. As Aurel Croissant argues, the highest pandemic-induced risks appear to be either to citizens of autocracies or to those in “democracies with pre-existing conditions.”Footnote 60 At the time of writing, consolidated democracies—especially those with substantial pre-existing limits on executive power and robust civil societies—had passed fewer coronavirus-related measures that threatened the quality of democratic institutions or compromised civil liberties.

Surveillance and Democracy: Understanding Democracy-Compatible Pandemic Response

How have consolidated democracies responded to the crisis conditions imposed by the pandemic without compromising the standards and quality of their democracies? The answer is not that democracies have eschewed surveillance or avoided tradeoffs and compromises on personal and data privacy. Privacy is a topic of ongoing debate in many contemporary democracies, and faced with COVID-19, most democratic countries employed some tracking or surveillance regimen.Footnote 61 Taiwan's response, for example, relied heavily on digital surveillance: data held by the National Health Insurance system was linked to data collected by immigration/customs and used to identify potential cases, conduct contact tracing, implement quarantine surveillance, and monitor citizens’ mobility patterns using government-issued cell phones.Footnote 62 Health records were also mined retroactively to identify, test, and treat individuals who had reported non-flu respiratory illness in the weeks before the outbreak became public. In South Korea, similar quarantines were maintained by requiring smartphone users to install an app that tracked the user's location—sometimes dozens of times a day—under post-2015 regulations that allowed warrantless remote access.Footnote 63 Yet both countries score well in terms of having avoided overall pandemic-related democratic erosion. How?

Successful democratic responses have generally adhered to three criteria: (1) measures adopted have been necessary and proportional; (2) measures have been temporally limited and limited in scope; and 3) measures have been subject to democratic processes of review and accountability. Moreover, in some democracies surveillance and monitoring are explicitly linked to positive citizen rights, such as the right to testing and treatment. Norms, institutions, and public opinion have jointly contributed to democracy-protective responses.

Policy responses have been proportional because surveillance technology has, generally speaking, been used by democracies to identify patients, separate the sick from the healthy, and determine risk levels stratified by subset of the population.Footnote 64 More extended periods of surveillance have been limited to a subset of individuals confirmed to pose a risk to others, with the boundaries of this subset specified in law and implemented with the intent of limiting other rights violations that could be considered equally or more severe, such as violations of citizen rights to mobility, commerce, assembly, and welfare that accompany widespread illness and/or mandatory lockdown. The negative frame is also helpful here: democracies have generally not employed surveillance technologies to target, harass, or curtail the freedom of the executive's political opponents in particular.

Access to and use of the data collected by surveillance technology for coronavirus management in democracies has also been temporally limited and limited in scope of access—in other words, both the time that data can be retained and who can access it are circumscribed. Taiwan, for example, requires personal data to be deleted after the fourteen-day quarantine period ends; the government has announced that that it will erase the whole monitoring system after the pandemic has passed and conduct audits to confirm that no data has been inappropriately retained.Footnote 65 Digital Minister Audrey Tang has argued that this transparency is necessary in order to equalize the power dynamic between citizens and government: as surveillance makes citizens legible to the government, transparency makes government legible to citizens.Footnote 66 South Korea allows for the collection of health-related surveillance data without prior court order during infectious disease outbreaks, but has also placed temporal and bureaucratic scope limits on digital data collection and retention. Only a few government officials can access the data integration platform, and their activities on the platform are monitored to avoid misuse. South Korean law also requires the government to delete all personal data collected once “relevant tasks have been completed” (once the pandemic has subsided).Footnote 67

Democratic pandemic responses have also been subject to democratic oversight and accountability. Taiwan's approach, developed during the 2003 SARS outbreak and subsequently ratified by the Constitutional Court, provides for both judicial review and legislative ratification of policies adopted under emergency health conditions.Footnote 68 When pressed publicly about whether Taiwan needed to use emergency powers to cope with COVID-19, President Tsai Ing-wen stressed that Taiwan could and would try to work within the existing legal framework in order to protect democratic processes and institutions. South Korea, too, learned from the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2015 to create what one analyst called a “bespoke legal regime tailored to meet the demands of an infectious disease outbreak.”Footnote 69 Although it empowers the government to use warrantless surveillance (as outlined above), the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act also places limits on government action and requires the health minister to regularly disclose certain information to the public for purposes of transparency and accountability.Footnote 70 In the early weeks of the pandemic, as critics expressed mounting concern that adherence to the law was leading to release of personally identifiable data, the National Human Rights Commission issued recommendations amending the scope and type of information made public, and the Korean CDC adopted those recommendations in mid-March.Footnote 71 These examples illustrate the role that both civil society and institutional checks and balances can play in constraining and tailoring pandemic responses by democracies.

In some cases, democracies have pursued not only bottom-up, citizen-based oversight, but pandemic response through participatory governance; some of these efforts have involved the private sector or public-private partnerships. In Norway, for example, over 1.4 million citizens (out of a total population of 5.5 million) downloaded to their smartphones a coronavirus tracking app developed by state-owned company Simula: essentially a form of opt-in, voluntary surveillance.Footnote 72 After Amnesty International identified privacy issues with the app, however, the government suspended its use and deleted the data it had gathered—an example of both voluntary participation and subsequent civil society oversight at work. In fact, voluntary participation and cooperation with private-sector solutions are characteristic of the approach taken to health monitoring in many democracies: European authorities, for example, have recommended voluntary programs due to privacy concerns, and opt-in citizen participation has therefore been essential to the functioning of the tools employed.Footnote 73

A number of democracies have also linked the expansion of government surveillance and authority during the pandemic to corresponding citizen rights. In South Korea, citizens are given the right to certain information (as discussed above), and the government must also notify any persons placed under surveillance that they are being monitored. The government can mandate testing, but the same law also endows citizens with the right to diagnosis and treatment, and requires the government to pay the costs.Footnote 74 In Taiwan, individuals placed under quarantine are compensated, and Foreign Minister Joseph Wu has spoken publicly on the need for government service provision to quarantined individuals.Footnote 75 Other democracies have expanded citizens’ rights to specific forms of health care, unemployment benefits, and other welfare assistance. Thus far, however, there has been more attention in public and policy discourse to how democracies can avoid rights violations, and less systematic attention to variations in the positive rights extended to citizens by democracies under pandemic conditions. This reflects discussion in the comparative politics literature on the heterogeneous ways democracies conceptualize and implement citizen rights.Footnote 76

Within consolidated democracies, a number of factors appear to have combined to facilitate democracy-protective pandemic response. Some countries that have combined effective public health policy with democratic insulation—such as Taiwan and South Korea—have recent authoritarian history, which offers a heightened awareness of the costs of surveillance and experience with the mechanics of redesigning processes and institutions previously used for authoritarian surveillance to render them compatible with democracy. Moreover, experience with a major infectious disease outbreak allowed these democracies to debate, prior to the onset of the crisis, the tradeoffs involved in different policy options, and to decide which tradeoffs, safeguards, and checks and balances were most appropriate and important. Other democracies, such as those in the European Union, also had strong data privacy regulations in place before the pandemic for different reasons. Worldwide, democracy-compatible responses drew on institutional frameworks (existing laws that could cope with pandemic conditions, checks and balances on emergency response); normative commitments by elites (eschewing the use of emergency powers, relying on existing legislation, welcoming democratic oversight); and public accountability and participation (which can be seen either as an implied electoral constraint or as participatory democratic process).

A final beneficial factor is that the measures adopted by many of these democracies produced positive results in the first several months of the coronavirus pandemic: low case and fatality numbers meant less pressure on leaders to adopt draconian or undemocratic measures to deal with a mounting crisis. The initial success of some of these approaches, in other words, reinforced democracy-protective effects over time.

Conclusions and Future Research

To what extent has the COVID-19 outbreak and the augmented use of health surveillance technology that has resulted from it altered global conceptions of civil liberties, privacy, and democracy? How might longer-term patterns of liberal democracy be affected by the pandemic? In China, the outbreak has strengthened a pre-existing techno-authoritarian project aimed at “prevention and control” of threats to both public health and public order. Certain features of the international system—such as China's major power status, its global economic role, and its leadership in international organizations—suggest that China's model of illiberal pandemic response could diffuse worldwide. Other factors, however, such as the incomparability of China's political system to many other countries in the contemporary international system, suggest much more limited diffusion potential. To date, the pandemic has largely augmented existing trends, meaning that autocracies have been likely to respond in ways that infringe upon citizen rights, and weak democracies exhibit some risk of democratic erosion and pandemic-associated autocratization; surveillance, however, has played a limited role in these processes. Conversely, consolidated democracies have managed to navigate the initial stages of the crisis by and large without compromising democratic standards. When they have used surveillance, it has been fenced in by democratic institutions and rule of law; norms, institutions, and public opinion have worked together to facilitate pandemic responses that are (on balance) proportional, limited in time and scope, and subject to democratic oversight.

The initial impact of COVID-19 on privacy, civil liberties, and democracy worldwide suggests several fruitful areas of focus for policy and research. First, if the risks of democratic backsliding truly are concentrated in a handful of weak democracies, the United States and the international community could focus their efforts on these countries. Foreign assistance and training could assist these countries in crafting legal and regulatory safeguards around pandemic response—the use of surveillance technology and broader policy responses—so that their efforts prioritize and protect citizen rights and democratic institutions. The United States could also play a key role in more actively shaping global learning processes to share democracy-compatible best practices in coronavirus response, putting the weight of the international system's most powerful actor behind democracy-compatible diffusion processes. This could take a number of forms, from using international organizations to facilitate transmission of ideas to informally supporting global emulation of democratic, effective pandemic response models. Finally, recent evidence suggests that contemporary autocratization is incremental, but difficult to reverseFootnote 77—implying that the payoff will be greatest if the US and the international community can arrest democratic erosion before it happens, rather than trying to repair erosion after the fact.

As the world continues to assess the impact of the novel coronavirus on global democracy and liberal governance, several questions merit further investigation. What will the actual patterns of diffusion be as they relate to health surveillance technology, particularly the technologies used to combat COVID-19? How many liberal democracies worldwide already have legal frameworks (related to surveillance or more broadly) to respond to infectious disease emergencies, and how many are developing these frameworks now, in response to the challenges posed by the pandemic? What policies, pursued or proposed, are effective at protecting liberalism and democratic institutions, and which ones are ineffective over the medium-to-longer term? How might surveillance interact with other mechanisms of democratic erosion to generate varied scenarios for the distribution and trajectory of democracy worldwide, and how do policy responses differ for each of these scenarios? What are the ideal international fora in which to regulate and develop standards for the use of health surveillance technology, and what foreign policy tools would ensure that liberal rather than illiberal approaches prevail? The answers to these and other questions will help scholars and policymakers alike assess and respond to the pandemic's ongoing impact on civil liberties and democracy around the world.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Tanisha Fazal, Michael Horowitz, Michael Kenwick, Phillip Lipscy, David Stasavage, Erik Voeten, and participants in the Perry World House/International Organization symposium and the America in the World Consortium for helpful feedback. I also thank the America in the World consortium, a partnership between Johns Hopkins University, Duke University, and the University of Texas, and the Laboratory Program for Korean Studies of the ROK Ministry of Education and the Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016-LAB-2250001) for financial support.