Introduction

In 2015, at the height of the so-called European migration crisis, the Italian government instituted a new typology of reception centres for asylum seekers. An emergency response to a recurrent structural problem (Ambrosini, Reference Ambrosini2020), these centres were set up to obviate the capacity limitations of the ‘ordinary’ reception system, consisting of first-tier identification and screening centres, and second-tier facilities aimed at facilitating the integration of asylum seekers and refugees (Semprebon and Pelacani, Reference Semprebon, Pelacani, Glorius and Doomernik2020). The Extraordinary Reception Centres (Centri di Accoglienza Straordinaria, or CAS henceforth) set up in 2015 resolved the capacity limitations of the ordinary reception system by granting Prefetture (the provincially decentralised offices of the Ministry of Interior) the authority to institute them through a Public Tender bypassing the involvement, or indeed the consent, of the municipal administrations in whose territory CAS were opened (Novak, Reference Novak2019). This emergency response proved to be extremely successful vis-à-vis its aims, as, despite their ‘extra-ordinariness’, CAS would host over 75 per cent of the total asylum seekers population in Italy (SPRAR, 2017), making them an integral component of the dialectic of care and control that characterises the humanitarian management of EU borders (Walters, Reference Walters, Brockling, Krasmann and Lemke2010; Agier, Reference Agier2011; Novak, Reference Novak2019).

The following pages study CAS in a small Italian province, Macerata, through the prism of deservingness, a framework that has long been deployed for interpreting the content of social policies targeting different categories of migrants (Sales, Reference Sales2002; Anderson, Reference Anderson2013). This prism offers an understanding of differentiated social welfare policies that moves beyond the legal ‘identity’ of specific target groups to account instead for the criteria that concretely define who gets what and why (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000). The significance of this interpretive framework has already been asserted in relation to the asylum system in Italy. Chiara Marchetti (Reference Marchetti, Gozdziak, Main and Suter2020), for example, convincingly makes the case that, since 2015, decisions about who deserves protection are guided by perceptions about asylum seekers’ willingness to fully integrate into their receiving country’s community of value and to prove they can become a ‘good citizen’. In this ‘regime of deservingness’, she argues, migrants need to justify their presence in Italy and to take responsibility for the alleged burden they place on the economy and welfare system, a point also developed by di Cecco (di Cecco, Reference Di Cecco, Fabini, Firouzi Tabar and Vianello2019). These criteria, importantly, develop beyond the realm of formal administrative procedures. They are reproduced, transformed, or challenged by social workers and civil society actors involved in the management of reception centres (Marchetti, Reference Marchetti, Gozdziak, Main and Suter2020), and take on specific connotations in relation to local economic, political and historical configurations (Casati, Reference Casati2018). Studying CAS through the prism of deservingness, thus, shifts the analytical focus away from public discourses and formal procedures, towards an understanding of how practical interventions and programmes are concretely put in place (Ravn et al., Reference Ravn, Mahieu, Belloni, Timmerman, Glorius and Doomernik2020).

The following study contributes to this literature by focusing on two dimensions unexplored in the above studies. First, it focuses on accommodation standards. It identifies key axes of differentiation across CAS in Macerata and exposes the uneven geographies of entitlements that this differentiation produces. It argues that such unevenness selectively dis/enables asylum seekers to meaningfully participate in the social life of the communities where they reside. Second, the article focuses on the circulation of asylum seekers across CAS. It moves beyond the analysis of national legal frameworks, or of single towns, initiatives, and reception centres, focusing instead on the CAS system at provincial level, as this is the administrative unit at which immigration management functions, Public Tenders instituting CAS, and the latter’s management, are concretely put in place and organised. It argues that performance-based deservingness criteria (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas, Reference Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas2014; Ataç, Reference Ataç2019), i.e. expectations about asylum seekers’ conduct and behaviour, define the circulation of asylum seekers across, and their potential expulsion from, CAS’ uneven geographies, thus functioning as a disciplining mechanism.

The article rests on field research material collected over six months, between 2017 and 2019, and is methodologically guided by a geographical approach to institutional ethnography (Billo and Mountz, Reference Billo and Mountz2016). Such an approach moves beyond the legal and administrative provisions defining institutions as coherent and uniform, to uncover instead their unevenness and differential effects. Studying up CAS through the differential embodied experiences that they produce, uncovers the structures, effects, and relations that animate them. Such an approach is thus particularly suited for capturing the significance of deservingness criteria in the organisation of institutions such as CAS, as it looks within, through, and beyond the architecture, policies, texts, and problematics of the institution to understand how, why, and for whom (ibid).

Methods

Field research methods comprised the typical toolbox of institutional ethnography: following actors, spending time on the inside, event ethnography (ibid). Overall, the study below draws from ten interviews with government officials and over fifty with staff of organisations managing CAS, and from field notes of daily visits to twenty five CAS, of innumerable open ended interviews, encounters, and chats with asylum seekers, of discussions, banter and leisure time spent with them unrelated to my object of study, of participant observation in sites such as police offices, bus stations, mobile phones and food shops, and during events such as Italian lessons and food deliveries. Contrary to other contexts, accessing CAS in Macerata was relatively easy, especially so during the first bout of field research. After having established with an official in the Prefettura that there were no legal restrictions in this respect, I was able to visit CAS, unaccompanied and in spite of the reticence and/or ostracisation of some of the organisations managing them, at different times of the day and the week. These repeated and unmediated visits and encounters with asylum seekers lie at the heart of the arguments developed below. This research was approved by the SOAS Ethics Committee.

The next section argues that, despite the formal legal and functional equivalence of CAS, arrangements beyond the formal realms of law and administrative procedures delineate a profoundly uneven geography of accommodation facilities. The following section argues that such unevenness is systemically used to organise the circulation of asylum seekers across facilities, offering rewarding and punishing paths towards better/worse forms of accommodation that are premised on performance-based deservingness criteria. The last section elaborates on these findings.

Uneven geographies of entitlements

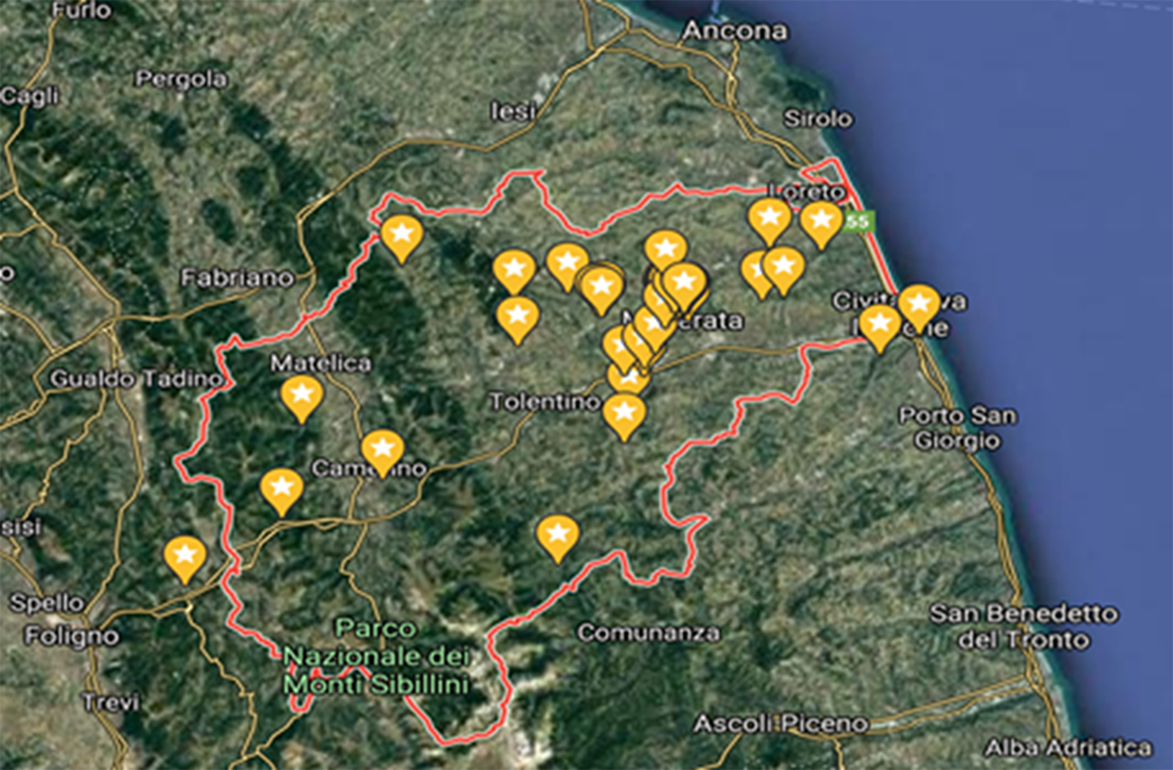

In the summer of 2017, there were sixty-five CAS scattered across the Macerata province (Figure 1). They hosted approximately 1000 asylum seekers, about 23 per cent of the asylum seekers hosted in CAS in the Marche Region, and 1 per cent of those hosted in such facilities across Italy. In line with EU Directive 2013/33 and with the Italian Ministry of Interior Legislative Decree instituting them (D.Lgs 142/2015), all sixty five CAS were meant to provide an adequate standard of living to asylum seekers, to guarantee their subsistence and to protect their physical and mental health. Housing standards, subsistence provisions and so-called ‘integration’ services that asylum seekers were entitled to whilst accommodated in a CAS are defined by the specifications contained in the Public Tenders organised by the provincial Prefettura. This equivalence conceals profound differences, which this section exposes.

Figure 1. CAS in Macerata province July 2017. The majority of CAS are in Macerata city, but at this scale are barely visible (see Figure 3 instead).

Source: the location of CAS was recorded on my phone (Google Maps) during my visits, for all CAS outside Macerata city. Those in Macerata city were either recorded in similar ways, or their address was recorded on the basis of a document from July 2017 provided to me by a Prefettura official.

Overall, CAS in the province were relatively small, as the Macerata Prefettura specified in the July 2017 Public Tender that no facility should host more than 100 asylum seekers. Only one large facility, a hotel, hosted that many. Three more hotels hosted eighty, thirty, and twenty-five migrants. Rural houses, former schools, or former B&Bs used as CAS across the province hosted between twenty and thirty asylum seekers each. The overwhelming majority of CAS (66 per cent of the total) was of a relatively small size (two to ten occupants), usually apartments in urban areas. Yet over 70 per cent of asylum seekers were hosted in the larger facilities (Figure 2, all data in this section refers to July 2017).

Figure 2. Number of CAS per number of asylum seekers hosted (July 2017).

Source: Author’s elaboration of figures provided by the Macerata Prefettura in 2017.

Variations in size do not necessarily correlate to heterogeneous standards inside each Centre. Rather, size directly correlates to the internal organisation of spaces. The two larger hotels, which were also open to the general public, would prevent access to communal areas and forbade asylum seekers from using the front entrance, forcing them to reach their room via the fire exit, i.e. stairs at the back of the hotel. The other two hotels being exclusively dedicated to hosting asylum seekers, offered instead full access to their grounds. One of them had a large garden, the other a more prosaic room on the ground floor, with one sofa, one armchair, a table, and a praying mat. In all hotels, food was served in a dedicated refectory at fixed times, and clothes could only be washed in specified timeslots and could not be dried outdoors. No electrical equipment could be brought to the rooms, meaning that a tea, for example, could only be bought in a public bar, rather than brewed at ‘home’. In most of the rural houses and B&Bs, instead, rooms hosting three/four asylum seekers were generally configured as mini-apartments or studio flats. Each was equipped with a, however small, common living area, a shared bedroom, bathroom and importantly a kitchenette, which allowed its occupiers to cook autonomously. In these cases, a (much cherished) monthly monetary food allowance would be added to the pocket money disbursed to all registered asylum seekers. Other facilities had instead a mix of dormitories for up to fifteen people and smaller rooms, offering their occupants access to one common area and to the adjacent grounds. In there, food was usually delivered by nearby restaurants or catering companies. Urban apartments, finally, would host five to eight migrants, who would share a kitchen, bathroom and common living space. Beyond the internal characteristics of each CAS, which seemed to shape disputes about space and personal belongings, most asylum seekers I spoke to would differentiate CAS by reference to two dimensions: remoteness and surveillance.

The most common signifiers used to describe the remoteness of their accommodation referred to the immediate social environment where each CAS was located, to the time taken to reach the first shop or urban centre or bus stop, to road safety risks and costs involved, to the proximity to Macerata, as opposed to any other urban centre in the province. While smaller units were in the proximity, if not the centre, of towns (see, for example, the location of CAS in Macerata city, Figure 3), most others were far removed from any urban conglomerate (Figure 4). The mostly hilly, agricultural landscape, with long connecting roads running through flatlands and historic towns perched up on the top of hills, means that shops, services and public spaces that could only be found in towns were out of reach for the majority of asylum seekers.

Figure 3. CAS in the city of Macerata (July 2017).

Source: The location of CAS was recorded on my phone (Google Maps) during my visits, or their address was recorded on the basis of a document from July 2017 provided by a Prefettura official.

Figure 4. CAS in the municipalities of Treia, Loro Piceno and Montecassiano.

Source: The location of CAS was recorded on my phone (Google Maps) during my visits.

Metric distance, i.e. the kilometres to the first shop or urban agglomeration, is the most obvious indicator of the relative remoteness of CAS in relation to urban centres (see Figure 4). The ‘trek’, as it was called by asylum seekers, between the facility in Loro Piceno to the centre of town, for instance, could take up to forty-five minutes along a steep uphill road. One facility ‘in’ Treia, i.e. within the area under the administration of the municipality, would be a one hour walk along a steep hill to the first shop – let alone to the actual town of Treia, a further one kilometre away. The trek between other CAS ‘in’ Treia to the nearest Eurospin, a discount supermarket where most asylum seekers would shop for food, would involve a twenty-five minutes trek along a fast connecting road. Getting to the centre of Treia municipality would involve an over one-hour walk. Indeed, most of the residents there would prefer to take a bus to Macerata, which had the added advantage of being the only place in the whole of the province where familiar spices, staples or drinks could be found in the two ‘African’ and the ‘Indian’ shop. As stated by an asylum seeker hosted in a rural house: ‘We are left here in the bush, lots of mosquito, we are segregated. I can’t go anywhere from here. Food finishes you don’t eat. Money finishes you don’t go out. I haven’t been out for a month. What am I supposed to do. Sleeping waking sleeping’. He was echoed, a year later, by another asylum seeker living in the same CAS: ‘We are lonely, in the middle of the bush, lots of mosquito. Nothing to do here. The school is far away [there was a forty-minute walk to reach another CAS, managed by the same contractor, where Italian lessons were being held daily, NfA]. To go there we trek then we rest then we trek, but it is too far. We asked for transport there and they told us that they don’t have any car available for that’.

Remoteness can also be defined in relation to the costs associated to getting from each CAS to urban areas. These involve monetary costs: for example, bus tickets, which would range between 2.5 Euros and 5 Euros for a trip to Macerata; an exorbitant amount of money considering the 2.5 Euros daily subsistence allowance received by asylum seekers. In the most peripheral CAS, the trip could cost over 8 Euros one way.

There were also other non-monetary costs involved. Public transport is scant in the province, with up to two hours wait for inter-municipal services connecting to Macerata. This is especially so in the central hours of the day and during the summer, as buses mostly cater to students. A trek to Macerata by bus would not only be very expensive, then, but it would also mean the disruption of daily activities, with language sessions, or visits by NGO workers, or lunch, at least in those facilities where lunch was provided through a refectory, most likely to be missed by those asylum seekers going to Macerata for shopping, for reporting to the police, or for any other reason. Such bus trips would also involve, much like the treks, risking one’s life, as getting to bus stops on connecting roads with no sidewalk was a risky affair. From this perspective, apartments in Macerata were certainly the most cherished CAS, as they provided immediate access to urban social life, however marginalising that experience might be. The relative remoteness of CAS, in other words, selectively dis/enabled asylum seekers’ meaningful participation in the social life of the communities where they reside.

The same consideration can be made in relation to surveillance mechanisms. Life inside CAS was regimented by a series of rules, which were clearly spelt out to asylum seekers upon arrival. ‘The supervisory gives us rules, and we follow them’, I was told by an asylum seeker. The most important one was set by the Prefettura, following national directives: a curfew requiring asylum seekers to be inside Centres by 11pm, and the obligation on the part of the managing organisation to enforce this curfew and to compile a daily report of presences. Beyond this, subcontractors would set up their own rules and enforcement methods in each facility. Most of these rules were common across contractors: for instance, forbidding asylum seekers from consuming drugs, alcohol, or cigarettes inside facilities. Other rules were CAS-specific, and would concern the regimentation of reproductive activities, whether these related to eating or laundry time slots (see above), or paternalistic instructions related to hygiene. Most asylum seekers saw the possibility of cooking and eating at the time of their own choosing, the presence/absence of a supervisor, the frequency and length of visits by managing organisations’ staff, the availability of adequate common and private spaces, as key axes enabling the possibility of conducting a, however regimented, autonomously set everyday routine. Here again, apartments in Macerata would offer the most autonomous form of living, with hotels the most regimented one.

Crucially, and as discussed further in the next section, surveillance and remoteness were strictly connected. At times, their relation was complementary. For example, in large and remote reception centres, especially so in the largest facility in the province, the remoteness from urban centres, the strict regimentation of everyday life in relation to refectory or laundry times, and the constant presence of a supervisor, would work synergistically to enforce and reinforce compliance to (and fear of) those rules. At times, this worked in contradictory ways. This was so, for example, in large CAS that were too remote for NGO staff to visit daily or that would be visited only during normal working hours. In these cases, remoteness performed in contradictory ways vis-à-vis those rules, as in the evenings and weekends there would be no one to enforce them. Of course, the occasional check by staff at night or on Sundays would remind everyone of their existence. In other CAS, this relation would be dependent on how supervisors approached their duties, as some were stricter than others in enforcing and reporting breaches of the rules, depending mostly on their personal inclinations. This was confirmed by one of the supervisors. When I was discussing with him the different supervision approaches I had witnessed, he stated: ‘Each of us does it differently: when people arrive I do a meeting with everyone involved, and I explain the rules, making clear that they cannot be breached. But then I stay with them and joke and all. I do not take signatures. People from [the contractor’s main office] come, they see the house is clean and everything is fine, they come another time, but then they stop checking the rooms upstairs’. In remote and isolated CAS, the curfew was effectively set by the availability of public transport, yet everyday life in these centres was largely self-organised with most rules (for example, smoking inside the premises) becoming irrelevant and constantly breached. At the same time, the absence of a supervisor meant that the feeling of isolation could increase, especially amongst new arrivals: ‘we have no supervisor here, nobody we can go to at any time’.

In sum, despite their legal and functional equivalence, and despite all contractors abiding to the same set of Public Tender specifications, each CAS visited seemed unique in terms of how housing facilities, remoteness, and surveillance articulated with each other in everyday life. Considering these uneven geographies, it is clear how being allocated to one or the other CAS profoundly shapes the experience of asylum, and the possibility of being part of the social life of surrounding communities. The next section moves beyond the internal characteristics of each CAS and their configuration, to consider the significance of these uneven geographies at systemic level.

Circulating across CAS

Using the two axes of differentiation identified above, it is possible to differentiate CAS into four broad typologies (Figure 5). In the top right box of Figure 5 are those CAS, mostly hotels, where everyday life routines such as eating or sleeping are set at fixed times, where the presence of staff and surveillance is high, with barely any common or private spaces. CAS in this box are depicted as quasi detention facilities, as the highly regimented everyday life is compounded by their remoteness from urban agglomeration de facto confining asylum seekers to their rooms. The largest CAS in the province would be the quintessential fit for this box. The top left box is populated instead by those CAS where levels of everyday life’s regimentation are similar, but which would be much closer to Macerata, thus offering the possibility of walking to the town centre, attending public events, meeting friends in public gardens or reaching them by bus.

Figure 5. A taxonomy of CAS.

At the bottom of the diagram sit instead those CAS where levels of regimentation are lower. At the bottom right, there are those where their remoteness prevents managing organisations to constantly monitor everyday life activities. While everyday life would run mostly at the discretion of their occupiers, their remoteness would confine them to a life almost without contact with the surrounding social environment, a condition of splendid isolation: located in what to the eyes of the external observer is a gentle green and hilly countryside, the remoteness of these centres meant that their occupants were not being subject to constant surveillance. In the bottom left box are those apartments in Macerata town considered by all asylum seekers as the ‘best’, as they displayed both low levels of regimentation and lower levels of remoteness. Despite these apartments being the largest proportion of CAS, or 66 per cent of the total, they would host less than 30 per cent of the total number of asylum seekers in the province. How to access them?

Upon arrival in the province, asylum seekers would be allocated to a subcontractor and later transferred by them to a hotel or large capacity CAS, with high levels of control and regimentation, described above as ‘quasi detention’ facilities. According to interviews with subcontractors’ staff, this was supposed to last no longer than three months, the time necessary for an initial orientation and support, for health checks and for lodging the asylum claim at the local police office. Interviews suggest, on the contrary, that this period could last up to one year or be prolonged indefinitely. After that, the asylum seeker would be transferred to other facilities, with lower levels of surveillance, or closer to town centres, before finally reaching an apartment in Macerata. These transfers would not be automatic, but rather depended on availability of places and, most importantly, on the judgements of subcontractors’ managers and staff about the deservingness of each asylum seeker.

As the manager of one NGO told me: ‘our hotel is where we put them first, and then we move them into the apartments. Of course, you privilege people who behave well, who do not make any trouble, who come to Italian lessons’. Similarly, the supervisor of one CAS confirmed that ‘Before you get to an apartment you need to behave; you know, they [asylum seekers] are very loud so first we need to handle them in a hotel and tell them about rules in Italy. If there is some fighting or if somebody breaks the rules, I will report that to my manager’. Indeed, another supervisor told me that being in a CAS is ‘like driving a car. I teach you the rules, I give you the tools, I teach you how to use them, I give you a direction, but it is up to YOU, you are the driver. From the beginning you need to show that you are willing to help, that you are well behaved. You are not here on holidays, you need to help, to talk to me’. As succinctly put by the President of one NGO: ‘it is not nice to say it, but there is a rewarding path that allows you to move out of our Hotel’. Figure 6 captures this rewarding path.

Figure 6. Rewarding paths.

This carrot would be accompanied by a stick: the indefinite delay in the transfer out of, or the return to, quasi detention facilities, as well as the potential expulsion from the CAS system. I collected several accounts of migrants being returned to these facilities for breaching the curfew, for fighting or engaging in heated discussions, for complaining about food or clothing or other matters. The same could be said by the threat of expulsion from the CAS reception system. For that, an Ordinance from the Prefettura was necessary, but this would usually rely on information provided by the contractor, as well as an interview. This system was clear to most asylum seekers, if not procedurally, at least in its substance. According to one of them ‘anyone which has frustrations and talks about them is kicked out of CAS’. For another, ‘If anybody had anywhere to go do you think they’ll spend one second in that place? That’s why you obey the rules. ‘After four days here’, someone else told me, ‘some people complained about food and they were getting angry and the NGO staff said, if you don’t like it this is where the door is, and you can leave anytime. So, people got scared and now they are all quiet’. As succinctly put by an asylum seeker: ‘If you obey rules you are fine, if not they kick you out’.

For some this system was fine: ‘there is time for everything, time to make money, to marry, to work. Here we have decent food, you can walk out and nobody will beat you, you are in a nice house, why do you want to smoke? Why do you want to go run around and do things to make more money? There is time for that. I now need documents’. For others, this created a sense of fear and paranoia. For most this was a temporary uneven geography to be navigated in order to pursue self-set lifegoals. For everyone, however, this incentive-based system was about to change, a confirmation that anything that happens inside a CAS is related to everything that happens outside it (Casati, Reference Casati2018).

In February 2018, a young Italian man went on a shooting spree in the streets of Macerata city. He fired gunshots at six black men and women, at the offices of an NGO managing CAS, and at those of a political party, unravelling a series of tumultuous social and political transformations in what had been until then a tranquil province. While until then the municipal administration had supported the establishment of CAS in Macerata’s main town and province, in spite of the growing resentment of many residents fuelled by local and national right-wing parties, a few days after the shooting, it decided to close all CAS in Macerata city (see Novak, Reference Novak2019 for a full account). Only a very small number remained open for unaccompanied minors and families, less than 1 per cent of the total number of asylum seekers in the province. Contractors were contacted by the Prefettura, were asked for the number and names of those hosted in Macerata city, and were notified that within a few days they would be forcibly transferred to other facilities outside town. In the latter, surveillance was tightened, with access becoming more difficult, with constant visits by staff, and an exponential increase in the number of checks by police in asylum seekers’ rooms and personal belongings. A military police (Carabinieri) patrol was moving daily around facilities. As stated by the Director Social Services of the Prefettura, ‘It is sad and a disaster, after so much work to build and construct a model that could work, that was working, a reception system that was a model… now it is all gone’.

Furthermore, the fear engendered by this violent act confined most asylum seekers to their rooms. For many this was a clear signal that it was time to move on and ‘jump’, i.e. seek access to another EU country. Many did and, by July 2018, there were 468 asylum seekers (less than half) in only thirty-seven CAS. In August 2019 almost all asylum seekers I had been talking to since 2017 had all but disappeared. Many had gone to France or absconded with friends across Italy; others were feeding the army of exploited agricultural labour across different parts of the peninsula. Of the ones remaining, very few were still in CAS. These were mostly cases deemed vulnerable (e.g. with mental health issues), or those who were chancing the last procedural appeal about their asylum case in Italian courts. Many were sleeping rough in the town’s central green area, or in squats near the station or in various parts of town. The system was shutting down, and it was envisaged that only two CAS would be present in the province by 2020 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Number of CAS in the province: July 2017 – July 2019 – 2020.

Source: the location of CAS was recorded on my phone (Google Maps) during my visits, for all CAS outside Macerata city. Those in Macerata city were either recorded in similar ways, or their address was recorded on the basis of a document from July 2017 provided to me by a Prefettura official.

Conclusions

Where rights are defined in law and are blind to individual particularities, deservingness is articulated in a moral register that relates to presumed characteristics and behaviour of the individual concerned (Spencer, Reference Spencer2016). For this reason, the above investigation moved beyond the realm of the law and of formal administrative procedures to account for the practices of exclusion and marginality that are obscured by CAS legal and functional equivalence.

The investigation was intended, first, to illustrate how in spite of standard formal provisions, informal practices associated to their organisation and management profoundly differentiate CAS across the province. These practices, including the organisation of intimate spaces, of subsistence and integration provisions, and the surveillance and regimentation of everyday life, delineate a highly uneven geography of asylum accommodation conditions and experiences, which selectively dis/enables asylum seekers to meaningfully participate in the social life of the communities where they reside. Second, the analysis moved beyond a simple enunciation of differences across CAS in the province, to account for their combined and uneven existence. It was argued that the circulation across and potential expulsion from CAS’ uneven geographies is premised on perceptions and judgements about asylum seekers’ deservingness. Performance-based deservingness frameworks establish rewarding/punishing paths towards ‘better’, i.e. more autonomous and less remote, forms of accommodation, diluting the formal right to an adequate standard of accommodation and subsistence.

The previous pages also accounted for the transformations that occurred in Macerata since February 2018. These transformations are to be inserted in broader politically-motivated dynamics occurring across Italy. A new right-wing government, installed in April 2018, began to transform the CAS system envisaging larger reception facilities, with fewer provisions and no integration services, with high levels of regimentation and remoteness. A system, in other words, where reception for asylum seekers is envisaged only in quasi-detention facilities akin to those at the top right box of Figure 6. This is a confirmation that the regime of deservingness that functioned until then had transformed into a regime of containment whereby there is ‘no need to invest in integration: there is no longer any ladder, or any ‘staircase of transition’ to climb (Marchetti, Reference Marchetti, Gozdziak, Main and Suter2020: 247).

Indeed, the above account demonstrated that if until 2018 the strategic management of asylum seekers’ circulation across CAS was premised on perceptions about the individual un-deservingness to better forms of accommodation, in this new regime un-deservingness criteria are applied collectively: all asylum seekers are to be accommodated in more remote facilities, with a higher level of surveillance. No asylum seeker, it seems, deserves to meaningfully participate in the social life of communities where they reside – regardless of how ‘well’ they behave.