On January 6, 2021, the US House of Representatives and US Senate held a joint session of Congress to count and certify the Electoral College votes for the 2020 presidential election. The typically ceremonial process was a final step before officially declaring Joseph Biden and Kamala Harris the next President and Vice President of the United States (Rybicki and Whitaker Reference Rybicki and Whitaker2020). However, Republican lawmakers complicated matters with their plan to oppose certifying the election results from multiple states—the latest in a string of ultimately unsuccessful efforts by Donald Trump and his allies to delegitimize the 2020 election (Kumar and Orr Reference Kumar and Orr2020). That afternoon, rioters from Trump’s “Stop the Steal” rally interrupted the proceedings by storming the US Capitol, resulting in more than 140 injuries to Capitol police officers and five deaths. Only hours later, after the insurrection had been suppressed, members of Congress reconvened to continue their work. Multiple Republican lawmakers walked back their previous intention to object to certifying the election results. Nonetheless, despite the events from earlier in the day, more than half of House Republicans still voted to exclude the election results from Arizona and Pennsylvania, continuing Trump’s unsubstantiated claims that widespread vote fraud cost him the election.

Why were some House Republicans willing to advance Trump’s position on the election during these roll-call votes and others were not? Why did House Republicans not unanimously reject Trump’s outrageous election-fraud claims and distance themselves from him after the Capitol riot? This article assesses differences in House Republican behavior during these electoral objection votes and accounts for various legislator and constituency characteristics to determine potential motivations for their decision making in the wake of the Capitol riot.

House Republican division following the attack on the Capitol demonstrates that even within the same party, members of Congress have diverse, overlapping motivations for their behavior (Green Reference Green2016; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1989). We focus on the following three considerations beyond party loyalty—which, of course, cannot discriminate among members of a single party:

-

• First, most members of Congress are responsive to constituent preferences, including district ideology, partisanship, and salient local-issue positions (Arnold Reference Arnold1990; Carson, Crespin, and Madonna Reference Carson, Crespin and Madonna2014). The logic of representative democracy dictates that legislators are sent to Washington to do what their constituents want them to do—and that they can be removed from office if they too often fail to comply.

-

• Second, members of Congress must consider strategically how a decision affects their reelection prospects, including from whom a lawmaker gains and loses support in terms of votes and resources (Burke, Kirkland, and Slapin Reference Burke, Kirkland and Slapin2020; Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005; Koger and Lebo Reference Koger and Lebo2017). Reelection concerns are particularly important to newly elected members in what Fenno (Reference Fenno1978) called the “expansionist phase” of their career and to anyone serving in a highly competitive district with narrow victory margins, regardless of career stage.

-

• Third, a Congress member’s ideology guides behavior, with important differences between a party’s ideological moderates and extremists (Carson, Crespin, and Madonna Reference Carson, Crespin and Madonna2014; Kirkland and Slapin Reference Kirkland and Slapin2017; Minozzi and Volden Reference Minozzi and Volden2013).Footnote 1

Green (Reference Green2016) assessed the influence of these factors when they examined House Republican division during the 113th Congress (2013–2014). At the time, Republicans controlled the House, but party leaders struggled with intraparty conflict, which was partially due to their party’s prioritizing conservative ideological commitments and partisan loyalty (Blum Reference Blum2020; Grossmann and Hopkins Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2016). Green (Reference Green2016) found that House members from more Republican districts, indicated by Mitt Romney’s 2012 vote share, and more conservative Republicans, indicated by their Dynamic Weighted (DW)-Nominate score, were more likely to oppose party leadership, whereas electoral considerations had no effect. Green (Reference Green2016) also found that a stronger partisan identity, operationalized by years in office, and personal connections with party leadership can explain differences in House Republican behavior. We used a similar approach to examine House Republican discord following the attack on the Capitol.

However, there are two critical differences about the intraparty division that we analyzed. First, in the 117th Congress, House Republicans are the minority party, whereas party-loyalty research like Green’s (Reference Green2016) focuses primarily on the majority party. As the minority party, several rewards from aligning with party leadership (Asmussen and Ramey Reference Asmussen and Ramey2018; Hasecke and Mycoff Reference Hasecke and Mycoff2007) are mainly absent. Facing a united opposition holding the majority, any dissent within Republican ranks would not change the outcome of any vote in Congress. Second, House Republicans were not deciding whether to support or oppose party leadership. Instead, the decisive roll-call votes were about supporting Trump’s election-fraud claims. Rather than loyalty to House party leadership, we assessed what motivated some House Republicans to align with Trump’s position following the Capitol riot. We included Green’s (Reference Green2016) partisan-identity explanation in our analysis. However, we did not test their personal-connection explanation, which focuses on a House member’s relationship with the Speaker of the House and therefore was not applicable in this analysis.

The decisive roll-call votes were about supporting Trump’s election-fraud claims. Rather than loyalty to House party leadership, we assessed what motivated some House Republicans to align with Trump’s position following the Capitol riot.

METHOD

We analyzed the roll-call votes for the Arizona and Pennsylvania electoral objections—two states that were won by Biden—where 121 and 138 of 209 House Republicans voted to exclude the election results from Arizona and Pennsylvania, respectively, thereby supporting Trump’s claims of election fraud. We used logistic regressions to determine what explains the variance during those votes. The dependent variable was dichotomous in each case, with values of 1 indicating a vote that aligned with Trump.

We operationalized constituent preferences by measuring district partisanship. We measured partisanship using Romney’s 2012 vote share in each congressional district.Footnote 2 District partisanship was expected to be a reasonably stable characteristic, and data from the 2012 presidential election predate any influence Trump had on the party.Footnote 3 We expected members representing more Republican districts to be more likely to align with Trump.

We measured electoral concerns by including each member’s most recent election performance and Trump’s popularity in their district. First, competitive general elections signal future electoral vulnerability, which generally “creates pressure for ideological convergence and moderation” (Hirano et al. Reference Hirano, Snyder, Ansolabehere and Hansen2010, 189). The converse of this argument is that large victory margins allow House Representatives to safely make controversial and/or extreme votes. If opposition to Trump’s election-fraud claims is viewed as the more radical or controversial vote among Republicans, we expected a House member’s vote share in the most recent election to be negatively related to support for Trump’s position.Footnote 4 Second, Trump’s ability to provide (or withhold) election resources to a House Representative and sway public opinion was expected to be a function of his popularity within a member’s district. We measured Trump’s popularity with the difference between his vote share in 2020 and the normal partisanship in a district, as measured by Romney’s vote share in 2012. We expected this variable to be positively associated with support for Trump on both votes.

With the electoral objections occurring only three days after the start of the 117th Congress, estimating the ideology of House Republicans elected in 2020 was considerably more difficult. Standard measures of ideology such as DW-Nominate (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1984), which is based on congressional votes, were not considered. We could have used DW-Nominate scores from the 116th Congress for incumbents reelected in 2020, but that would have excluded the 40 newly elected Republicans from the analysis. Instead, we used judgments provided by respondents in the 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) surveys about the ideology they perceived or attributed to the Republican (and Democratic) candidates running in their district (see online appendix A for more details on variable construction).Footnote 5 This measure, of course, is inherently less reliable than reports of one’s own ideology. We also indicated whether each representative is a member of the House Freedom Caucus (HFC), which is considered the more conservative wing of the Republican Party and was a staunch supporter of Trump (Green Reference Green2019; Rubin Reference Rubin2021). Given the Republican Party’s emphasis on ideological commitments (Blum Reference Blum2020; Grossmann and Hopkins Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2016), we expected more ideologically conservative Republicans to be more likely to support Trump’s position.

Green’s (Reference Green2016) partisan-identity explanation suggests that stronger party attachment increases alignment with the Republican Party’s position and a House member’s desire to help the party, which we similarly tested by measuring years in office and denoting current party leadership experience.Footnote 6 We expected members with greater party attachment to be less inclined to support Trump’s disruptive election-fraud claims as they seek to move the party forward and distance themselves from his position following the Capitol riot.

We included additional binary indicators for gender and nonwhite members.Footnote 7 Republicans prioritize party interests over individual identities, which is a challenge for those from underrepresented backgrounds who constantly must prove their loyalty (Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman Reference Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman2018; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2015; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021). The pressure of being from an underrepresented group should have motivated alignment with Trump among women and nonwhite Representatives as evidence of their ideological commitment and partisan loyalty.

We also included the percentage of nonwhite Americans in the district in our predictive models.Footnote 8 Trump’s attempts to undermine the 2020 election reflect the modern-day Republican Party’s agenda to disenfranchise minority voters—an effort motivated by changing demographics in the United States (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Anderson Reference Anderson2018; Bentele and O’Brien Reference Bentele and O’Brien2013; King and Smith Reference King and Smith2016; Piven et al. Reference Piven, Minnite, Groarke and Cohen2009). We expected that representing a more diverse district motivated House Republicans to align with Trump and his election-fraud claims because Republican Party fears of increasing diversity are especially relevant to these claims. Finally, we controlled for legislators from Arizona and Pennsylvania to account for unobserved motivations related to the fact that they represented districts in the states under scrutiny. To simplify the interpretation of coefficients, we rescaled all continuous variables to range between 0 and 1.

We expected that representing a more diverse district motivated House Republicans to align with Trump and his election-fraud claims because Republican Party fears of increasing diversity are especially relevant to these claims.

RESULTS

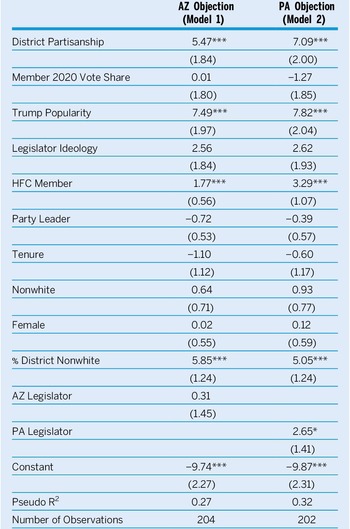

Table 1 presents the results of multivariate logistic regressions analyzing support for excluding Arizona and Pennsylvania’s election results, continuing Trump’s protest of the 2020 presidential election. House Republicans were responsive to constituent preferences because district partisanship, measured by Romney’s 2012 vote share, significantly predicted supporting both measures. Trump’s popularity—the difference between his 2020 vote share and Romney’s 2012 vote share in the district—represented reelection concerns and Trump’s ability to provide or withhold electoral resources. House Republicans representing districts where Trump was especially popular were significantly more likely to support the two electoral objections. Because the objection votes splintered House Republicans, the data in table 1 suggest that district partisanship and Trump’s popularity in a House member’s district were crucial factors in explaining vote choice.

Table 1 Determinants of Support for Arizona and Pennsylvania Electoral Objections

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1.

Ideological extremity also predicted support for the electoral objections. Whereas our measure of legislator ideology based on CCES survey data was not statistically significant, being a member of the HFC, the far-right wing of the Republican Party, predicted support for both electoral objections. Our legislator-ideology variable similarly explained voting behavior in an alternative model in which we did not control HFC membership (see online appendix B2). Furthermore, we produced similar results when measuring legislator ideology using DW-Nominate scores from the 116th Congress, excluding the 40 first-term Republicans (see online appendix B3). When we controlled for other variables in the equations, more conservative House Republicans were more likely to support excluding Arizona’s and Pennsylvania’s election results.

Other than being a representative from Pennsylvania, which weakly predicted support for the Pennsylvania objection (see table 1, model 2), no other variable explained either objection vote except for the racial composition of a House member’s district (see table 1, models 1 and 2). House Republicans rarely represent diverse constituencies. Their average congressional district is 18.4% nonwhite and the percentage in Democrat districts is almost double. The average congressional district of House Republicans who supported either objection is 19.3% nonwhite and 15.7% nonwhite among those who supported neither—a statistically significant difference (p<0.01). Nonwhite constituents increased a House Republican’s likelihood of voting to exclude the two election results. This relationship reflects the fact that the Republican Party is the home for white Americans’ concerns regarding changing demographics in the United States, with vote-fraud claims being one of several GOP tactics to disenfranchise minority voters as a response (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Anderson Reference Anderson2018; Bartels Reference Bartels2020; Bentele and O’Brien Reference Bentele and O’Brien2013; Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014; King and Smith Reference King and Smith2016). House Republicans who represent congressional districts where diversity is more prominent aligned with Trump and his efforts to overturn the election—and, presumably, to prepare for similar tactics in future elections.

A House member’s vote share in the last election, tenure in office, being a party leader, and race and gender all failed to explain either roll-call vote. In contrast, district partisanship, Trump’s popularity, legislator ideology, and the proportion of nonwhite constituents all explained House Republicans’ decision to align with his election-fraud claims following the Capitol riot. To test the robustness of our findings, we were interested in how applicable our findings were to other instances of House Republican division after January 6. One week after the attack, the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Trump for “incitement of insurrection”—a charge that seemed accurate to anyone who viewed the events on television—but only 10 Republicans voted with a unanimous Democratic Party for impeachment. Months later, a May 19 vote to set up the bipartisan January 6 Commission to investigate the attack divided Republicans when only 35 House Republicans supported this action. We recognize that these votes included additional considerations not present in the two objection votes recorded on January 6, but we conducted a similar analysis given their relatedness.

A House member’s vote share in the last election, tenure in office, being a party leader, and race and gender all failed to explain either roll-call vote. In contrast, district partisanship, Trump’s popularity, legislator ideology, and the proportion of nonwhite constituents all explained House Republicans’ decision to align with his election-fraud claims following the Capitol riot.

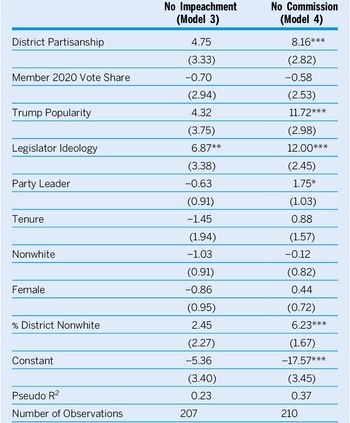

Table 2 presents the analysis of House Republican opposition to impeaching then-President Trump for his role in the Capitol riot (model 3) and establishing a bipartisan commission to investigate the attack (model 4).Footnote 9 Both instances—but especially the impeachment vote—were less divisive than either electoral objection. As a result, none of our variables explained voting against impeaching Trump a second time except ideology.Footnote 10 Meanwhile, district partisanship, Trump’s popularity, and legislator ideology predicted voting against establishing the January 6 Commission, just as they predicted support for the two electoral objections. Being a party leader also weakly predicted opposing the commission (p<0.1). Finally, although our interest in district diversity was primarily about the electoral objections, the racial composition of a House member’s district also strongly predicted voting against establishing the January 6 commission. This arguably is the case because such a commission surely would have concluded that Trump’s claims of widespread vote fraud were unfounded, thereby undercutting any such claims in future elections.

Table 2 Determinants of Opposing Trump’s Impeachment and the January 6 Commission

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1.

CONCLUSION

For many Americans, the egregious actions on January 6, 2021, became synonymous with the excesses and outrageous claims made by Donald Trump during his presidency. House Republicans did not confront this reality equally, however, because many remained publicly committed to Trump’s skepticism of the election. We sought to identify potential motivations for this behavior, viewing it primarily as calculated political decisions. Our approach addresses why House Republicans aligned with Trump’s voter-fraud claims. From the other perspective, readers who are interested in understanding why some Republicans had the fortitude to oppose Trump’s baseless claims can simply reverse the signs in the tables.

As expected, representing a more Republican district strongly predicted supporting both electoral objections. However, we went a step further, measuring the change in district partisanship since 2012 to demonstrate the specific influence of Trump’s popularity. It appears that Trump’s demands for loyalty and electoral threats for disloyalty may have resonated with many House Republicans. Trump’s popularity in a House member’s district—evidence of his ability to sway public opinion in that district—was strongly related to Republicans aligning with his voter-fraud claims following the Capitol riot. Although it is too soon to know as we write this article, based on these findings, Trump’s political vision may continue to dominate Republican politics for years to come. We also found that more nonwhite citizens in a House Republican’s congressional district increased their likelihood of supporting the exclusion of election results based on alleged election fraud—claims that we again expect to reappear in future US elections.

We found no evidence that standard measures of electoral vulnerability (e.g., narrow victory margins) were related to supporting the former president’s position once we controlled for his popularity in a district. Moreover, we did not find that a House member’s gender or race had any significant influence on any of the votes, controlling for the other variables in the model. Overall, our findings regarding House Republican division following the January 6 Capitol riot indicate the relevance of constituent preferences, Trump’s popularity, ideological differences, and the racial diversity within congressional districts represented by Republicans.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OSVICI.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096521001931.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.