Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 is a thirty-year-old policy whose implementation continues to be debated today among all three institutions of government in the United States.Footnote 1 Although current debates focus on gender equity in athletics, Title IX legislation as originally written did not even mention sport. Title IX states: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving federal financial assistance” (P.L. 92-318 sec. 901). In fact, Title IX arrived on the agenda specifically to combat sex discrimination in education. In particular, those who fought for its passage focused on issues such as equal pay, tenure track opportunities, and sex bias in school texts.Footnote 2

So how and when did the focus of Title IX shift from gender equity in education to gender equity in sport? What factors led to this shift? To fully understand the evolution, it is necessary to place Title IX’s development in its historical institutional context. Drawing from arguments made by historical institutionalists, this study highlights the importance of analyzing “organizational configurations rather than particular settings in isolation,” and it pays particular attention to critical junctures and long-term processes rather than simply “slices of times and short term maneuvers.” Footnote 3 In this case, the shift in Title IX policy that took place in 1973 can be seen as critical within the long-term historical development of this policy. During this period, Title IX’s policy community shifted its focus from education to sport, and Congress reformulated Title IX legislation to include athletics. This is critical because the shift in focus and redefinition to athletics continued to frame the Title IX debate from that point forward.Footnote 4 Further, this shift occurred within an organizational context involving all three branches of government and reflected an appropriate historical context, all of which created the right timing for policy change. This article examines the institutional structures and processes, as well as the favorable political and social context, that created the proper timing and favorable conditions for Title IX’s redefinition to include sport.

The literature on Title IX thus far does not provide a systemic historical institutional evaluation of its policy development. Much of the literature examines Title IX’s development from a “bottom-up” approach. The evolution of Title IX from this perspective is explained largely by pressure from outside interest groups and lobbyists.Footnote 5 The legislation’s history supports this approach to a certain extent, for interest groups did focus their arguments on gender inequity in athletics soon after Title IX’s passage. The question still remains, however: Why did these groups narrow their focus from larger issues of gender discrimination in education to gender equity in athletics at that particular time? And how did this shift get translated onto the agenda within the institutions of government?

Some literature on Title IX does focus on the policy-making process. Fishel and Pottker, for instance, provide a detailed analysis of how Title IX progressed through Congress and the executive branch from 1972 to 1975.Footnote 6 Joseph McCarthy’s analysis of Title IX extends through 1988, which includes the court’s role in Title IX’s policy interpretation in the 1980s.Footnote 7 Other accounts explain its development in relation to women’s public policy issues.Footnote 8 In addition, there are many law review articles that focus on Title IX’s judicial history.Footnote 9

Scholars have also provided guidance on the proper implementation of Title IX.Footnote 10 For instance, in Tilting the Playing Field: Schools, Sports, Sex, and Title IX, Jessica Gavora contends that the executive branch has incorrectly interpreted and implemented Title IX legislation in recent years.Footnote 11 And in Title IX, Linda Jean Carpenter and R. Vivian Acosta analyze how it applies to physical education, recreational activities, and athletics and provide a full congressional, executive, and legal history and evaluation of Title IX’s current status.Footnote 12 None of the literature to date, however, examines policy change within Title IX’s larger historical institutional context. Although this article focuses on one critical change in Title IX’s development, it does so from a historical institutional perspective by examining the institutional processes, especially the relevant individuals and political and social events that came together to create the perfect timing for agenda setting and change. In turn, this early shift in Title IX’s policy agenda began as a dialogue that has continued over the statute’s policy meaning and application since that time in response to shifting historical conditions and factors.

The early development of Title IX underscores the crucial importance of “timing” for understanding policy change. Drawing from concepts presented by Pierson and Kingdon, this study highlights the importance of temporal context, timing, and unintended consequences.Footnote 13 From one perspective, “timing” can refer to the moment at which an event occurs in history. In this case, social context created a fertile environment for a shift in thinking about women’s participation in athletics. “Timing” can also refer to political institutional processes that create opportunities for policy change.Footnote 14 At this point in Title IX’s history, processes involving all three institutions of government created timely and concurrent opportunity for change. While the executive branch formulated Title IX regulations, Congress simultaneously sought to clarify its intent, and the courts created precedent on the issue of gender equity in athletics. These institutional processes created opportunities for policy dialogue and development within a social and political context energized by an increased awareness of gender equity in sport.

The history of Title IX also supports the truism that policy often develops from unintended consequences.Footnote 15 As Pierson argues, policy change often occurs not as the result of heated conflict and well-designed pressure from outside groups, but instead, as the result of more mundane and routine institutional processes. Although the shift in Title IX’s focus to athletics came at a critical point in its history, we cannot explain this shift simply by looking at pressure from and conflict among outside groups. Athletics became the central issue among the institutions of government not because of overwhelming pressure from outside groups for the inclusion of athletics in Title IX policy and not because of the actions of dominant political actors, but instead because athletics arose as the primary source of contention among those groups directly affected by Title IX policy and by the institutional policy-making processes occurring at the time. Although outside groups pushed for Title IX’s passage, the eventual focus on athletics occurred as an unintended consequence.Footnote 16

Drawing from historical institutional theory in general, and those theories presented by scholars such as Kingdon and Pierson that stress the temporal aspects of policy change, this article analyzes Title IX’s development as part of a larger systemic historical process. This study adds to the literature theoretically by taking a cross-institutional approach by examining the institutional processes that occur simultaneously across all three branches of government to shape policy development. An overall examination of Title IX’s early development reveals that its applicability to athletics arrived on the policy agenda through a complex process—the result of external group conflict along with the issue’s simultaneous development and discussion among all three institutions of government within a social environment that enhanced political awareness of gender equity in sport. It grew, in effect, into a “perfect storm.”

SOCIAL CONTEXT AND TIMING

The development of Title IX occurred within a sociopolitical environment that contributed to the right timing for institutional and policy change concerning gender equity for women in athletics. On the one hand, the social context at the time highlighted women’s athletic abilities; on the other, it is important to note that Title IX would not have passed if it had been legislated much later. Key participants at the time contend that the lack of social and political awareness in the early 1970s helped Title IX’s passage and the shift to athletics. Because of the “newness” of the issue and the uncertainty at the time as to how the feminist agenda would play out politically, the battle lines had not yet hardened. In interviews with Bernice Sandler and Margot Polivy, two women at the center of Title IX’s early development, both women stressed the importance of political timing. Polivy argued specifically that 1972 was the last year of the “freebies” because the “right wing” had not focused on it yet.Footnote 17 At the outset, initiatives like the ERA and Title IX could thus pass without much resistance, but once Congress sent the ERA to the states, the conservative reaction congealed. Sandler, as well, pointed out that if Title IX had come any later, opponents would have figured it out and there would have been a “whole bunch” of exemptions.Footnote 18

Sandler also discussed the nascent social awareness of women athletes. As one of the individuals responsible for helping to write Title IX legislation and putting together the original hearings on Discrimination Against Women in 1970, Sandler underscored the change between 1970 and 1973. She recalled that in 1972, at the time of Title IX’s passage, there were five or six people who knew Title IX would cover athletics, but those individuals originally involved in getting Title IX onto the agenda had no idea of the impact Title IX would have on athletics. They had no real understanding of women and sport. When Congress enacted Title IX, Sandler’s sense of how Title IX would cover athletics was in terms of more activities for women on field day! According to Sandler, when Margot Polivy entered the picture, she became the link to the sports establishment. In 1970, Polivy served as an assistant to Representative Bella Abzug, but by 1973 she had become an attorney for the American Intercollegiate Athletic Association for Women (AIAW) and was one of several individuals working to incorporate athletics into Title IX policy within the context of the Education Amendments of 1974. Sandler stressed that Polivy taught “the originals” about sports for women.

In the early 1970s, female athletes also became more visible socially and politically. For instance, Billie Jean King testified in congressional hearings in 1973 and became the first female athlete to win $100,000 in a single year. The first women ran the Boston marathon in the late 1960s and, statistically speaking, athletic participation by women increased across the board in high schools, colleges, and universities.Footnote 19

Furthermore, when asked her opinion about the shift from education to athletics in Title IX’s focus, Polivy stressed social pressure from the bottom up. She noted that during this time there was a series of court cases brought by fathers of athletically talented daughters at the junior high school level.Footnote 20 This normative shift in thinking by men about their daughters as athletes illustrated and accelerated the shift in thinking about women as athletes at the time. Polivy also argued that inequality was easier to explain visually through sport. People could understand it more easily than “sex role” stereotyping.

The environment at the time also fostered an increased awareness of women’s athletic abilities. One of the most memorable events in athletics in 1973 was the “grudge” tennis match between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs.Footnote 21 That spring, Riggs easily beat the top-ranked woman tennis player, Margaret Court, in an exhibition match for $10,000. King felt that she had to respond, especially since women’s tennis was only just beginning to address long-existing discrimination.Footnote 22 Indeed, Riggs set himself up as the epitome of a confident male chauvinist. He told one news source: “Hell, we know there is no way she can beat me. She’s a stronger athlete than me and she can execute various shots better than me. But when the pressure mounts and she thinks about fifty million people watching on TV, she’ll fold. That’s the way women are.”Footnote 23

The largest crowd ever to witness a tennis match (30,472 people) assembled in the Houston Astrodome to watch this “battle of the sexes,” while a “Super Bowl–size TV audience” (approximately 50 million people) watched the match on television.Footnote 24 Unaffected by all the hoopla and Riggs’s attempts to “psych” her, King took control of the match early on, and won in three straight sets. She walked away with the $100,000 purse as well as her share of $200,000 in ancillary rights.

This match generated much public attention and King’s decisive victory had enormous symbolic importance.Footnote 25 Gloria Steinem, noted feminist leader, recalled women on college campuses hanging out of their dorm windows celebrating. King summarized it best herself, saying simply, “I don’t think they realized that this little tennis match was going to do this to them. It wasn’t about tennis, it was about social change.”Footnote 26 This event, which occurred in 1973, indicates the larger societal environment within which Title IX policy development occurred.

The timing is also relevant. As one news journalist indicated at the time, timing was everything. “Five years ago these superheated matches could not have happened, and five years from now they would not mean anything. But Riggs, properly overaged and frivolous, came along at the confluence of two phenomena: the rise of Women’s Lib and the country’s need, more desperate than ever, to be entertained. Watergate, inflation, shortages—the catalogue of ills is dispiriting to contemplate. Some buffoonery and sex offer a welcome change.”Footnote 27 The shift in Title IX policy to incorporate athletics fits well within the social context that was shifting its perspective on women in sport.

Female athletes at this time also began to challenge negative stereotypes about women in athletic competition. Throughout much of the twentieth century, social and medical authorities impressed upon women that sports would cause “women problems” such as infertility.Footnote 28 Olympic Skier Suzy Chaffee, for instance, had been discouraged from competition by the head ski coach at Denver University because “it was bad for the ovaries.”Footnote 29 One of the first women to run a marathon, Katherine Switzer, also cited the myth that if women ran they would never have babies or attract men.Footnote 30 She officially entered the Boston Marathon in 1967, but did so by using only her initials on the application.Footnote 31 Come the day of the race, as she ran alongside her boyfriend and her coach from the Syracuse Cross Country team, a truck carrying marathon officials pulled alongside her. After being egged on by the media, the marathon’s head official, Jock Semple, jumped off the truck and attempted to tear the official entry numbers off her jersey, all the while yelling at her to get out of his race.Footnote 32 Switzer finished the race in a little over four hours, but only with the help of her fellow male track team members and coach, who surrounded her and prevented race officials from pushing her off the course.Footnote 33 Not until four years later, in 1971, did the New York City Marathon become the first to officially include a women’s division.

Also in the early 1970s, pathbreaking articles began to appear in popular journals and newspapers discussing the change in women’s athletics.Footnote 34 As an example, in July 1972, the New York Times included a large article, with multiple pictures, entitled “For-Men-Only Barrier in Athletics is Teetering.”Footnote 35 The article discussed the rising participation of women in athletics and cited examples from a range of sports, including riflery, horse jockeying, crew, marathon running, skiing, football, baseball, and hockey. The article described how, in 1972, Mrs. Bernice Gera won a six-year legal battle for the right to become professional baseball’s first woman umpire. And it discussed the existence at the time of an all-woman pro football league that had teams in New York, Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh and an all-girl hockey league in Boston. Most important, this article conveyed to the public that it was normal for women to engage in athletic competition. “If competitive athletics have valid, positive contributions to make for males,” observed one male women’s track coach, “why shouldn’t athletics do the same thing for females?”Footnote 36

Sports Illustrated (a magazine with a predominantly male readership) also drew attention to gender inequity in athletics. A three-part series in 1973 highlighted the unequal opportunities for women in sport. One article demonstrated the gross inequity in expenditure and quality of women’s versus men’s programs. A second disproved the commonly accepted belief that sports were risky and inessential for girls. The third article entitled, “Women in Sport—Programmed to be Losers,” argued that limiting girls’ access to athletic competition may turn them into underachievers, because without athletics they missed the values of aggressiveness and winning that boys experience.

Also noteworthy was the change in media coverage after Title IX. The articles that appeared in Sports Illustrated in 1970–71 conveyed a very different view of women’s role in sport than the 1973 series. These articles depicted female athletes more in terms of their appearance than their athletic skill. One author and coach of a girls’ high school basketball team wrote of one comely athlete: “She went up high and she had the best looking legs of any basketball player I had ever seen.” Indeed, “they’re the prettiest basketball players I’ve ever seen … and two of them can make layups.”Footnote 37 Another article on the 1971 U.S. Girls’ Junior Golf Championship described the athletes thus: “She had one of the most confident walks ever seen, her perfectly tanned, well-formed legs swinging jauntily.”Footnote 38 The articles published in 1973 called attention to the benefits of athletics for women and the entrenched inequities that prevented women from attaining these benefits rather than their appearance while playing.

From the late 1960s through the early 1970s, the time period within which Title IX’s policy community formulated and defined Title IX to include sport, evidence suggests that a normative shift began to take place in larger society. Popular articles focused on women as athletes and on the issues of equal opportunity for women in sport. Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs, a man, in a highly publicized media event. Women fought to become official entrants in marathon races with the help and support of their male counterparts. And fathers brought legal action on behalf of their daughters’ rights to play sports. Politically the timing was also perfect because the opposition to gender-equity issues was not yet well formed. Title IX’s policy community thus addressed gender equity in athletics within an expanded and inviting social context.

INTEREST-GROUP CONFLICT, UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES, AND EXECUTIVE PROCEDURE

Unlike the initial push for Title IX, athletics arose on the agenda as an unintended consequence of the interest-group conflict surrounding Title IX’s passage through the regulatory institutional processes.Footnote 39 On one level, focus turned to athletics primarily because of those groups fighting against Title IX. Those opposed to Title IX, such as the NCAA and the American Football Coaches Association, drew attention to an issue that the women’s groups originally fighting for Title IX had ignored. Also relevant were the institutional processes through which Title IX progressed at the time. Athletics emerged as the primary issue of contention as the executive branch began writing regulations. And letters written to congressional members at the time focused on Title IX’s projected impact on athletics. Evidence of external group pressures clearly illustrate that athletics became the primary source of contention during the regulation-writing process, and that those who had fought so hard for Title IX as originally legislated would not have targeted athletics if their opponents had not deliberately drawn attention to the issue.

Although female coaches and other women involved in the sports establishment experienced discrimination, they had no connection with those feminists in Washington fighting for Title IX.Footnote 40 As an example, six months before Title IX’s passage, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) formed in a bid to govern women’s intercollegiate athletics. The NCAA responded almost immediately by competing directly with the AIAW for control of women’s intercollegiate athletics. The NCAA also lobbied both the Congress and the executive branch to exclude athletics from Title IX regulations. The NCAA’s actions produced an unintended consequence by raising the AIAW’s awareness of the political potential for Title IX to further women’s opportunities in athletics. As Mary Jo Festle has noted, however uncertain “women in PE” felt about Title IX, “the more they discovered how strenuously men in sports opposed equality, the more clear it became how important Title IX could become.” As the male sports establishment claimed with increasing stridency (especially to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare) that “equality would mean the end of intercollegiate sport,” the AIAW pushed back. In short, men’s opposition caused “AIAW women into taking a strong position in favor of the regulations sooner than they otherwise might have.”Footnote 41

At first the AIAW feared that if Title IX mandated absolute equality, it would not allow women’s sports to maintain separate rules and more gender-defined ways of playing sport.Footnote 42 Athletics thus became the focal point—not because there was overwhelming pressure from the outside that demanded gender equity in sport, but because it emerged as the primary issue of contention within Title IX’s policy community. As Martha Derthick states, “The absence of conflict … does not signify the absence of change, and what is routine, though it may not be interesting to analysts at a given moment, is cumulatively important.”Footnote 43 Gender equity in sport, not gender equity in the classroom, morphed into the hot-button issue as Title IX progressed though the normal institutional processes, an unintended consequence of normal policy processes.

As the executive branch formulated Title IX’s regulations, input from outside sources filtered to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) from a variety of sources, including other executive departments as well as Congress. The DHEW received much of this input prior to the official release of Title IX’s proposed regulations in June 1974. Interest groups and interested individuals thus initially responded to “leaks” about the developing regulations through means other than the formal public comment period.

The NCAA became the key outside group that received and acted on preliminary information about the developing regulations. In a memorandum to President Nixon, Secretary of Education Caspar Weinberger indicated that “considerable controversy” had engulfed “sex discrimination in collegiate athletics” because the NCAA had misinterpreted “an early, preliminary draft of the proposed Title IX regulations, which unfortunately was leaked to the public mid-winter.”Footnote 44 Mistakenly thinking that the draft required equal expenditures for male and female competitive athletic programs, the NCAA proposed language to exempt revenue-producing sports, such as football and basketball, from Title IX’s requirements.Footnote 45

Congressional members also forwarded constituents’ letters to President Nixon concerning Title IX’s regulations. “I have already heard from close personal friends of mine expressing their foresight and concern over these proposed regulations,” Olin Teague (R-Tex.) wrote to Nixon, arguing that “these regulations will generate unnecessary problems and present havoc for collegiate and intercollegiate athletics.”Footnote 46 In one letter to Teague, Warwick Jenkins, a lawyer for concerned administrators and faculty at Baylor University, charged that HEW was drafting regulations in “such a manner as to virtually destroy intercollegiate athletics and seriously impair priorities in intramural athletics.”Footnote 47 His critique of the regulations focused on equal expenditures. Notwithstanding “some disparity between the expenditures for women’s athletics and those for men’s,” Jenkins claimed that “this is really not a woman’s field and it seems to me that judging on the basis of numbers and other contributions is really not the test in the field of athletics, and particularly in intercollegiate athletics.Footnote 48 Jenkins based his analysis on information received from Robert C. James, chairman of the NCAA Legislative Committee. Jenkins enclosed an evaluation of the regulations by James in his letter to Teague. The exchange of letters between Teague, his constituents, and President Nixon illustrate the key role of the NCAA in framing the debate over Title IX’s proposed regulations. Such letters indicate that outside interest groups were able to access internal information prior to its official public release, and thereby attempt to have an impact on policy development outside the formal policy-making process. Regular institutional processes (the open comment period) provided the opportunity for policy change, while extra formal processes, leaks, and misinterpretations led to a focus on athletic funding, which in turn framed the debate.

Individuals and women’s groups in favor of athletics under Title IX regulations also found the means to respond. Aside from working with congressional members supportive of women’s interests in education, such as Patsy Mink (D-Hawaii) and Edith Green (D-Ore.), many of these individuals and groups accessed the process through appropriately positioned bureaucrats in the administration. As Kingdon discusses, “hidden participants” in the process often shape policy outcome from behind the scenes.Footnote 49 For instance, in March 1974, Anne Armstrong, Counselor to President Nixon, passed on three letters addressed to the president that indicated a well-developed opposition to the NCAA’s position. In his response to Armstrong, Weinberger noted a “great deal of comment, much of it from women college athletic instructors, urging the Department to retain an athletic section in the draft regulation. On the other hand, many male college athletic directors have commented in support of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s position that the section should not be included.”Footnote 50 Without judging the merits, Weinberger acknowledged the developing dispute between men’s and women’s groups and the issue of Title IX and athletics.

Vera Hirschberg, director of Women’s Programs for the Nixon administration, also heard from citizens concerned about “the implications for physical education and athletics of the regulations to implement Title IX.”Footnote 51 Much input came from women’s athletic directors. For instance, in March 1974, in response to Penelope C. Hinckley, dean in the Department of Athletics and Physical Education at Princeton University, regarding the implications of the proposed regulations for intercollegiate athletics, Hirschberg assured Hinckley that her office had been working closely with the appropriate individuals in the Office of Civil Rights to make the regulations equitable.Footnote 52 Interested individuals and interest groups thus found ways to provide input in the regulation-writing process even before regulations were released, and the conflict among these groups riveted the policy community’s attention on Title IX’s application to athletics.

When DHEW released its proposed regulations in June 1974, Weinberger announced a four-month comment period, lasting through October 15, 1974, rather than the standard thirty days. This would allow ample time for public consideration of the issue and give educators and school officials an opportunity to prepare comments after schools reopened.Footnote 53 DHEW thereupon received an unprecedented 9,700 comments concerning Title IX’s regulations.Footnote 54 As two scholars note, “over 90 percent of those comments related to the application of Title IX to athletics,” even though “less than 10 percent of the regulations deal directly with athletics, physical education, recreation or sports.”Footnote 55 It had become glaringly apparent that gender equity in athletics had emerged as the most controversial issue.Footnote 56

In December 1974, Weinberger received a series of questions about the proposed regulations from Kenneth Cole, assistant to the president for Domestic Affairs. In his response, Weinberger noted that Title IX’s application to competitive intercollegiate athletics was “the single most controversial issue in the Title IX regulation based upon public and Congressional interest.”Footnote 57 And again, when the DHEW released its final regulations to the public in June 1975, Weinberger identified athletics as “certainly the most talked about issue.”Footnote 58 And in a memorandum written to the president in February 1975 concerning Title IX’s final regulations, Weinberger once again reiterated that “although certainly not the most important educational subject under Title IX, this issue has raised the most public controversy and involves some of the most difficult policy and legal points.”Footnote 59

In another example, in January 1975, the White House Office held an informational meeting and discussion with outside groups that focused on education programs in the HEW with a particular emphasis on women’s programs.Footnote 60 Weinberger, the first speaker, reviewed many of the department’s programs and then fielded questions from the audience. Mary Allen, president of the Intercollegiate Association of Women Students, immediately asked: “What position will HEW take on comments regarding the impact of the Title IX regulations on athletics? I think this issue is the one over which the largest battle has and will take place.”Footnote 61 Weinberger agreed. “I think you are right that this is the largest battle.”Footnote 62 Thus, according to public response, congressional input, and executive evaluation, athletics was the most controversial issue, thus requiring a “timely” policy response regarding gender equity in athletics within the institutions of government.

The debate among groups outside the institutions of government, however, did not provide a clear indication of what the public wanted.Footnote 63 The DHEW thus had to weigh in with its own policy response. Public input may have focused the agenda, but individual and institutional incentives and resources within the executive agencies involved ultimately determined policy formulation and direction. Further, because Congress had not provided a clear indication of its intent, the executive branch had more leeway for its own evaluation and response.

For instance, in a memorandum written in March 1974 from Weinberger to the president,Footnote 64 Weinberger outlined the DHEW’s proposed regulation and then argued for its superiority in comparison to the NCAA’s position. The NCAA then put forth its position in the Tower amendment in June 1974, which proposed to exempt revenue-producing sport from Title IX regulations. Weinberger predicted that women’s groups would be displeased with the DHEW’s compromise proposal. Although the DHEW was required under Title IX statute to cover activities conducted by recipients of federal financial assistance, the “proposed regulation has been drafted in such a way as to minimize the impact on existing competitive athletic programs, because to do otherwise would in [his] opinion create a serious backlash against women’s rights.”Footnote 65 The proposed regulation allowed educational institutions to provide separate competitive athletic teams for males and females, required schools to provide opportunities for women and men in competitive athletics based on their expressed interest in participating, and specifically did not require equal aggregate expenditures for athletics for both sexes.Footnote 66

Weinberger believed that the department’s plan leaned toward the NCAA’s position. Although it acknowledged that “the enforcement of Title IX statute [would] necessarily bring about some changes in the existing pattern of intercollegiate athletics,” it also minimized these changes to the extent that the law permitted them to do so.Footnote 67 For this reason, Weinberger predicted that numerous women’s groups would attack the HEW’s proposed regulations for not going far enough.

Other institutional factors and political events also helped create the appropriate timing for Title IX’s policy community to focus its attention on athletics as a component of gender inequity in education. In the executive arena, an awareness of Title IX’s impending passage and a lack of a clear congressional directive created incentive to evaluate Title IX’s application to athletics. The executive branch’s need to formulate regulations for Title IX opened a policy window for discussion of athletics as an element of gender equity in education. By the time Congress passed Title IX and handed the executive the task of formulating regulations, the executive branch had already evaluated the issue within the relevant agencies.

The Office of Education (OE) (the agency in charge of education before the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare) took early steps in anticipation of Title IX’s passage. In fact, OE had defined athletics and physical education as part of educational equity well in advance of the official regulation-writing process and well before 1974, when Congress amended the Title IX statute to include athletics. In May 1972, the Commissioner of Education, Sidney P. Marland Jr., established a twelve-member Task Force on the Impact of OE Programs on Women in response to the “rising public concern about discrimination against women in education” and for the purpose of investigating the impact of Office of Education programs on women.Footnote 68 The ensuing Report of the Commissioner’s Task Force on the Impact of Office of Education Programs on Women included a key paragraph on athletics as evidence of sex bias within the education system in 1972.Footnote 69 The report found that girls, at the time, got “short shrift” in physical education because “schools and colleges devoted greater resources to boys’ than to girls’ athletics: in facilities, coaches, equipment and interscholastic competition.”Footnote 70 It also made the connection between physical fitness and education. “Schools sponsor physical education and extramural sports because educators recognize the importance of the life long habits of physical fitness.”Footnote 71 The report acknowledged the importance of these habits for women, “as workers and mothers,” as well as for men.Footnote 72 Its release in November 1972, just five months after Title IX’s passage, demonstrates that at least one agency had acknowledged athletics as a part of public education well before Congress gave any other clear indication of congressional intent on Title IX’s application to athletics.Footnote 73 Despite no suggestions for agency action on athletics in education, the acknowledgment of sex bias in education and athletics indicates problem recognition in the executive arena.

In the executive arena, therefore, the need for Title IX regulations created the opportunity for policy development. Even before Title IX’s passage in 1972, in preparation for the regulation-writing process, the Office of Education evaluated the impact of OE programs on women. The open comment period in 1974 provided an institutional political event that opened a policy window in the executive arena. These events provide two examples of how executive procedures helped create the proper timing for Title IX’s policy focus to shift to gender equity in athletics.

CONGRESSIONAL PROCEDURE

Within the same time frame, congressional procedures also created opportunity for policy redefinition. As the executive arena proposed regulations, those in the congressional arena found ways to voice their opinions and clarify legislative intent. In particular, the impending expiration of the Educational and Secondary Education Act of 1965 provided the opportunity for creating the Education Amendments of 1974, which in turn prompted further congressional discussion of Title IX policy and offered a forum for communicating with the executive arena regarding regulations.

In 1974, the House and Senate both proposed bills (H.R. 69 and S. 1539) to amend and extend the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. These bills and their related hearings provided a window for Congress to clarify legislative intent concerning education and athletics.Footnote 74 Congress cleared the resulting conference report on July 31, and President Ford signed it into law on August 21, 1974.Footnote 75 This law, known as The Educational Amendments of 1974, included two sections pertaining to sex discrimination in athletics.

The first section relevant to sex discrimination in athletics fell under Title IV, Section 408, which concerned the consolidation of certain education programs. Section 408, entitled “Women’s Educational Equity,” was one of seven new programs to be funded.Footnote 76 The program was directly related to Title IX in that it provided the Commissioner of Education with the means to implement activities designed to provide educational equity for women. Its relevance to Title IX policy on athletics became readily apparent in the legislative hearings held on this act, which included witnesses who testified to the importance of athletics as a component of an individual’s educational experience.Footnote 77

The second provision relating to sex discrimination was Section 844, under Title VIII, “Miscellaneous Provisions.” It declared that “the Secretary shall prepare and publish not later than 30 days after the date of enactment of the Act, proposed regulations implementing the provision of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 relating to the prohibition of sex discrimination in federally assisted education programs which shall include with respect to intercollegiate athletic activities reasonable provisions considering the nature of particular sports.”Footnote 78 This section, known as the Javits amendment, specifically addressed the need for the completion of Title IX regulations and provisions for athletic activities within those regulations. The other branches of government would later refer to the Javits amendment as evidence of congressional intent concerning Title IX and gender equity in sport.

WOMEN’S EDUCATIONAL EQUITY ACT

The development and passage of the Women’s Education Equity Act largely resulted from individual and interest-group efforts. Arlene Horowitz, a clerical worker for the Education and Labor Committee in the House of Representatives, had the idea for the bill and authored the first draft.Footnote 79 Like Bernice Sandler, whose personal frustrations led to Title IX legislation, Horowitz’s restiveness with her own employment motivated her to consider political action.Footnote 80 She believed that her job made inadequate use of her education and political experience, and she blamed societal sex-role stereotyping for placing women like herself in such inferior positions. Having attended seminars on women’s issues and holding a position in the government that exposed her to numerous education bills aimed at specific issues, she thought in terms of a bill that would change attitudes about women in society by focusing on curriculum development in elementary and secondary schools.Footnote 81 In this case, Arlene Horowitz’s involvement highlights the importance of “hidden participants” in the development of public policy.Footnote 82 As a committee staff member, Horowitz had personal access to individuals directly tied to the agenda-setting process and thus the potential to make her voice heard.

Horowitz eventually contacted Bernice Sandler, a leader in the Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL) and a central figure in the Title IX policy community. As Sandler recalled, she and Horowitz met for lunch one day; they bought sandwiches and sat on a bench on the Capitol grounds and talked at length about Horowitz’s idea for her bill.Footnote 83 Sandler thought the idea was a long shot—in her own words, “crazy,” but she put Horowitz in touch with other interested women within the Women’s Equity Action League; these women soon developed a second draft and found an appropriate congressional sponsor. They chose Patsy Mink (D-Hawaii) for several reasons. Although not considered a feminist, Mink was both a woman and senior ranking member on the Education Subcommittee in the House of Representatives, where the bill would most likely be referred after its introduction. Horowitz also knew her because the Education Subcommittee on which Mink served was chaired by John Brademas (D-Ind.), for which Horowitz was a staff assistant. Receptive to the idea, Mink proposed hearings on educational discrimination against women and girls in order to establish on record a clear need for the bill.

The first time Patsy Mink introduced the Women’s Education Act (H.R. 14451) on April 18, 1972, it died as expected because she had introduced it too close to the end of the 92nd Congress. Her intent, however, had been to launch a trial balloon to receive some preliminary feedback.Footnote 84 As a result, the bill came to the attention of Senator Walter Mondale (D-Minn.), who asked Mink if he could sponsor the bill in the Senate.Footnote 85 According to Horowitz, it was Arlene Fraser, an active member of WEAL and the wife of Representative Don Fraser (D-Minn.), who knew the Mondales personally and drew his attention to the bill.Footnote 86 Senator Mondale seemed a good fit as a member of the Senate Education Subcommittee, which would most likely have to approve the bill.

On the first day of the 93rd Congress in January 1973, Patsy Mink reintroduced her bill with some modifications. As renamed, the Women’s Educational Equity Act of 1973 (H.R. 208) sought “to authorize the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare to make grants to conduct special educational programs and activities designed to achieve educational equity for all students, men and women, and for other related educational purposes.”Footnote 87 Subsequently, the bill was referred to the Education and Labor Committee, which referred it to the Subcommittee on Equal Opportunities, of which Mink was a member.Footnote 88 The chair of this subcommittee, Augustus Hawkins (D-Calif.), assured Mink that the bill would receive attention if requested. Mink requested two days of hearings in July and two days in September. Senator Mondale requested hearings to be held in the Senate Subcommittee on Education of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare in October and November 1973. Both hearings elicited significant testimony.

The July hearings in the House invited witnesses from twelve organizations representing a broad range of the national women’s and education groups in the country, such as WEAL, the National Women’s Political Caucus, the Council for University Women’s Progress, and the National Foundation for the Improvement of Education. Many of these groups discussed gender equity in athletics as a relevant topic.Footnote 89 For example, Arvonne Fraser, president of the Women’s Equity Action League, described sex discrimination in athletics as “the area where sex discrimination is most pervasive and most readily apparent.”Footnote 90 As evidence, she noted the unequal per capita expenditures on athletic activities by sex, unequal access to facilities, lack of coaches for women’s activities, and discouraging attitudes concerning women’s participation in athletics.Footnote 91

Senator Mondale introduced the Women’s Educational Equity Act in the Senate on October 2, 1973, as “a logical complement to Title IX.Footnote 92 The Senate Subcommittee on Education of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare held hearings on S. 2518 in October and November 1973. In particular, Billie Jean King’s testimony in November drew considerable attention.Footnote 93 Senator Mondale had been the only senator to show up in October, but when King testified, five senators attended and her appearance made the national news. This meant favorable publicity for the bill and added focus on the issue of women in sport. According to Sandler, King’s testimony definitely had the right impact. It drew attention to WEEA, which passed relatively quickly. Just as important as having five senators in attendance was the increased number of staffers in attendance. Sandler contends that staff members in attendance drew attention to WEEA, which, for a smaller bill, passed relatively quickly.Footnote 94 Staffers do not dictate but certainly provide cues to their senators and representatives to pay attention to certain issues. Senator Mondale’s staff, in fact, orchestrated the tennis star’s appearance. Ellen Hoffman, a member of Mondale’s staff, was in charge of putting together the hearings.Footnote 95 As Hoffman recalled, Mondale and his staff asked King to testify to draw attention to the issue and stimulate support from both the grass roots and within Congress.Footnote 96

King’s star quality propagandized the benefit of athletics for women. Her testimony stressed the benefits of athletic involvement for all individuals. She reflected on what athletics had done for her personally and described the discrimination she had experienced as a female athlete throughout her career. In particular, her testimony discussed the symbiotic relationship between intellectual and social growth and athletics.Footnote 97 She recounted how playing sports helped students with discipline and time management and the connection between being physically fit and mentally sharp.Footnote 98 King criticized the NCAA for its monopoly on college athletics and for fostering a system in which college athletes were actually professional athletes. This argument highlighted, once again, the conflict at the time between women’s groups in Washington, women’s athletic groups, and the NCAA. It also began a debate that continues today over the professionalization of college athletics.

A second and equally important point concerned society’s perception of female athletes. Senator Richard Schweiker (R-Pa.), for instance, asked King how equity would solve such problems as “breaking down among girls and women the concept of the “unladylikeness” and also the matter of jumping from say swimming and tennis to some other sports, and how do we educate society on the social mores that obviously are involved?”Footnote 99 King replied that “so many women” have “the potential to be athletically inclined, and they are just afraid, but if through these educational programs, if you do fund athletic programs and girls find out it is fun, they find out that they are accepted, in fact they are looked up to, this will change everything.”Footnote 100 Little girls would go home and tell their families how much fun they were having, which would change perceptions. And if women’s sports become professional, girls and boys would have new role models of successful female athletes, which would also encourage a change in social mores. Indeed, little boys told King that they wanted to be great tennis players like her. They did not think of her as a woman or a man; they knew her as an athlete.Footnote 101

King discussed several other possible changes. She pointed out that “money is a measuring stick” for success.Footnote 102 People valued her based on her financial success as a professional tennis player.Footnote 103 If more professional sports opened to women, and prize monies increased, it would facilitate a change in the public’s perception of women athletes. The media’s role was also changing the public’s perception of women athletes. Sports writers no longer wrote about “‘Cute blue eyed petite da-da boo-boo.’… They do not start a story about a male athlete the same way.”Footnote 104 Change was occurring within families as well. For instance, King cited mothers who wanted their little girls to have the same opportunities as their sons.

Other witnesses testified in the Senate hearings on the issue of sports for women. Women such as Bernice Sandler and Helen D. Wise, president of the National Education Association, referenced athletics in their testimony. Dr. Wise prepared a statement for the record that emphasized the importance of athletics for women. “If schools are to provide for the needs of girls, they must move to open educational opportunities beyond those that have traditionally existed.”Footnote 105 According to Wise, given that school programs had traditionally distinguished between sports and physical education programs for girls and boys, the Women’s Educational Equity Act, S. 2518, would help to eliminate some of the inequities and create more educational opportunities for women.

Although Title IX as legislated in 1972 forbade discrimination on the basis of sex in all federally assisted education programs, it did not create new programs for direct assistance to women.Footnote 106 Congress offered solutions to this “problem” in committee hearings on the Women’s Educational Equity Act of 1973. These hearings provided another opportunity for the policy community to debate athletics as a component of gender equity for women in education. In contrast, the hearings on Discrimination Against Women that took place in 1970 and the groups and individuals involved in Title IX’s legislation had not included discussion of athletics as a part of educational opportunity. In terms of timing, in 1973, while those in the executive arena debated congressional intent concerning athletics for women in Title IX, those in the congressional arena clarified their intent on Title IX through both statute and hearings related to the Education Amendments of 1974.

On August 21, 1974, President Gerald Ford signed the Education Amendments of 1974 (P.L. 93-380) into law, which included both the Women’s Educational Equity Act (Section 408) and the Javits amendment (Section 844). Section 408 of P.L. 93-380 authorized funding for several activities to achieve educational equity for men and women, and included the establishment of an Advisory Council on Women’s Educational Programs in the Office of Education.Footnote 107 The significance of the Women’s Educational Equity Act for Title IX’s development was not only that it provided funding and an advisory council, but also, through the hearings, that it drew more attention to sex bias in education and provided one of the first political institutional forums for the discussion of gender equity in sport. The Javits amendment, in particular, would subsequently be referenced by executive officials as a clear statement from Congress on the meaning of the Title IX statute as it applied to athletics.

THE JAVITS AMENDMENT

The Javits amendment specifically instructed the Secretary of HEW to issue proposed regulations for Title IX within thirty days of the passage of the Amendments, and furthermore stated that the regulations should make “reasonable provisions” for intercollegiate athletic activities.Footnote 108 Ironically, in this case, what began as a legislative proposal to exclude athletics from Title IX policy resulted in a policy that expanded the meaning of Title IX specifically to include intercollegiate athletics. The Javits amendment thus provides a conspicuous example of how policy change often occurs as the result of unintended consequences.

On May 20, 1974, in anticipation of the soon-to-be-released proposed Title IX regulations, Senator John Tower (R-Tex.) proposed an amendment to exempt revenue-producing intercollegiate athletics from coverage under Title IX. He claimed that the HEW had mistakenly “interpreted Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 to provide it with the authority to promulgate rules governing sex discrimination in intercollegiate athletics.”Footnote 109 According to his recollection and subsequent investigation, he insisted that Congress had not intended for Title IX to extend to intercollegiate athletics. Further, he argued that the proposed HEW rules would damage the revenue-raising ability of collegiate sports programs and thereby the overall sports program of the institution. This in turn would diminish the ability of the college or university to provide increased athletic opportunities for women.

In the middle of his statement, Tower modified his amendment to include a proposal made by Senator Mondale (D-Minn.).Footnote 110 In a compromise agreement, Mondale agreed not to oppose Tower’s amendment if Tower would add the requirement that the commissioner prepare and publish regulations implementing Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 within thirty days of the passage of the Education Amendments of 1974.Footnote 111 The Senate agreed to the Tower amendment, now including the Mondale proposal.

In conference committee, however, the Javits amendment replaced the Tower amendment. The Javits alteration left Mondale’s proposal intact, but it severely changed Tower’s proposal. Instead of exempting revenue-producing intercollegiate athletics from Title IX policy, the Javits amendment required Title IX regulations to include “reasonable provisions” concerning intercollegiate athletics. The conference committee also agreed to a House-passed provision that gave Congress forty-five days after the publication of DHEW regulations to veto the regulations by concurrent resolution if they found them inconsistent with congressional intent.Footnote 112 If Congress did not pass a concurrent resolution within the forty-five days, then the regulations would automatically go into effect.

What happened in conference committee? Margot Polivy, an attorney for the American Intercollegiate Athletic Association for Women (AIAW) at the time, has recalled that the Javits amendment was actually scrawled on an envelope on Representative Shirley Chisholm’s (D-N.Y.) back in the hall outside the conference committee.Footnote 113 Carol Burris from the Women’s Lobby also participated in drafting the amendment. In conference, it seems that Tower agreed to the Javits amendment because Pell, the subcommittee chairman, promised to hold hearings at a later date on Tower’s main issue concerning Title IX and revenue-producing sports. Tower reintroduced his amendment as a bill in 1975 (S. 2106), after the release of Title IX’s final regulations. Although the Senate hearings on the Tower amendment generated a great deal of debate within the policy community, the Senate did not vote on or pass S. 2106.

Timing and priorities clearly facilitated the passage of the Javits amendment. Margot Polivy remembered that the Javits amendment was “small potatoes” in comparison to the much larger appropriations bill within which it was ensconced.Footnote 114 The appropriations bill needed to be passed, and “small potatoes” like the Javits amendment were not going to hold up its passage. The passage of the Javits amendment thus illustrates how political context, interest groups, and unintended consequences can have an impact on the timing and substance of policy change. The agreements made among Tower, Mondale, Javits, and Pell reflected the compromises that accompany and often shape policy formulation.

This story also demonstrates how a policy’s original intention (i.e., the Tower amendment) can produce a completely unintended, if not opposite, outcome. The need to get the appropriations bill passed framed the political context and affected the timing of the bill’s consideration and passage. Policy change thus flowed from unintended institutional incentives and resources. Polivy’s statement about the political context also reflects the importance of political timing in policy formulation. What was seen as “small potatoes” prior to ERA’s passage would not have been viewed so afterward. Last, the fortuitous involvement of Carol Burris from the Women’s Lobby and Margot Polivy from AIAW outside the conference room with Javits as he wrote his amendment demonstrates the relevance of outside organized forces.

The Javits amendment also facilitated congressional communication with the executive arena. First, the Javits amendment stated congressional desire for executive action on Title IX regulations. Although Congress did not enact the Education Amendments of 1974 until August 1974, the Javits amendment prodded HEW into proposing Title IX regulations on June 20, 1974.Footnote 115 Second, documentary evidence indicates that individuals within the executive arena considered the Javits amendment an expression of congressional intent as they formulated Title IX’s final regulations. For instance, in October 1974, John B. Rhinelander, General Counsel, in responding to the Secretary of DHEW’s question about whether “Title IX must deal with intercollegiate sports that produce, through gate receipt or otherwise, significant revenue to universities and colleges,” included a detailed account of how Congress replaced the Tower amendment, which would have excluded revenue-producing sports from Title IX coverage, with the Javits amendment, thereby specifically stating Title IX’s application to intercollegiate athletics.Footnote 116 Because the statute did not differentiate between revenue and non-revenue-producing sports, there seemed to be no basis for exempting “such sports and their revenues from coverage by Title IX.”Footnote 117 As Rhinelander noted, “The legislative history together with the statutory language, finally enacted through the Javits amendment, leaves no doubt that Congress intended Title IX to apply to competitive athletics and did not intend to exclude from its application revenue-producing athletics.”Footnote 118 The Javits amendment thus illustrates Title IX’s simultaneous development across institutions and the cross-institutional communication that shaped Title IX policy as it applied to sport.Footnote 119

THE COURTS

The courts also contributed to the dialogue and shaped Title IX policy at this key historical juncture. As the executive branch struggled to formulate Title IX’s final regulations, it did so with further input from Congress, as well as through consideration of judicial activity. The overall development of judicial precedent concerning gender equity in athletics paralleled its development in the executive branch and the legislature. The Supreme Court also received its first cases filed under the Equal Protection Clause involving sex discrimination in high school athletic programs.Footnote 120 These cases were not filed under Title IX but did indicate judicial opinion on a woman’s right to gender equity in education and athletics under the Equal Protection Clause; the executive branch cited these decisions in the process of formulating Title IX regulations. At this juncture, these athletic cases did not need to address the issue of whether or not sex was a suspect classification; instead, they had to establish whether or not the classification based on sex, which denied women participation in athletics, bore a rational relationship to a state interest. Under the Fourteenth Amendment, the Equal Protection Clause had been construed to apply only when “state action” was shown.Footnote 121 The Court, therefore, had to establish whether or not administering programs of interscholastic athletics for state high schools constituted “state action” within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.Footnote 122

In general, equal protection claims brought by female student athletes arose in three distinct situations.Footnote 123 The first concerned the failure by an educational institution to fund a noncontact sport for women, while at the same time prohibiting women from joining the men’s team.Footnote 124 The second scenario involved a claim against a school that did provide a separate program for women, but the plaintiff wanted to gain entry to a men’s team or invalidate restrictions on competition between the separate teams.Footnote 125 In other words, female athletes made the telling argument that separate was not equal. The third situation involved the failure by a school to provide a contact sport for women, while at the same time prohibiting women from joining the men’s team.Footnote 126

A case from the first category, Brenden v. Independent School District, Footnote 127 will illustrate the court’s role in the development of gender equity in athletics as a policy issue. (See Table 1 for other cases that arose at the same time.) The Brenden case is relevant for several reasons. First, the courts decided the Brendan case in 1973, one of the first cases the courts received concerning equity in athletics. Members of the executive branch thus referenced Brenden as support for the inclusion of athletics in Title IX coverage. (As an example, see the discussion of the Dixon letter below.) Second, the 8th circuit court of appeals adjudicated the Brendan case at the very time that Congress held hearings on WEEA, which included reference to athletics in education. Third, the opinion in this case cited congressional and executive activity in the development of judicial precedent concerning sex discrimination in athletics and education, thereby underscoring once again the cross-institutional dialogue during this period of Title IX’s development. Last, the facts of the case illuminate the social and political context in which gender equity in athletics developed as a public policy issue.

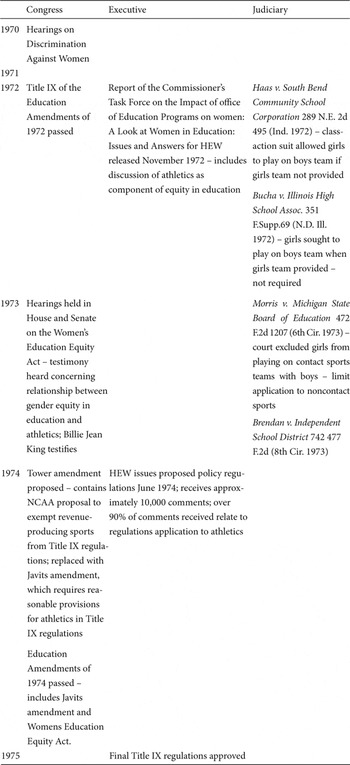

Table 1. Activity relating to Title IX within each policy arena from 1970 to 1975

In Brenden, two female Minnesota high school students, Peggy Brenden and Antoinette St. Pierre, filed to enjoin the enforcement of rules prohibiting interscholastic competition between men and women. Both plaintiffs were exceptional athletes, Brenden in tennis, and St. Pierre in cross-country skiing and cross-country track, but their schools did not provide competitive teams for females in these sports. The schools offered interscholastic competition in these sports for men only. The plaintiffs were denied the opportunity to try out for the team because of the Minnesota State High School League’s rule barring girls from participating in male athletics.Footnote 128

As their primary defense, the defendant highs schools argued that the purpose of the league rule was “to insure that persons with similar qualifications [would] compete among themselves.”Footnote 129 They further argued that the physiological differences between males and females made it impossible for females to compete equitably with males in athletic competition.Footnote 130 The defendants’ expert witnesses testified that “men are taller than women, stronger than women by reason of greater muscle mass; have larger hearts than women and a deeper breathing capacity … [and] run faster, based upon the construction of the pelvic area.”Footnote 131 The appellate court disagreed and affirmed the lower court’s ruling in favor of the plaintiffs.

The court relied on the test used by the Supreme Court in Reed v. Reed Footnote 132 and found that this sex-based classification had “no fair and substantial relationship to the objective of the league rule.”Footnote 133 The court further believed that Reed precluded a state from using assumptions about the nature of females as a class.Footnote 134 In the Brenden case, the two girls were barred from competition based on assumptions about the qualifications of women as a class. The court determined, therefore, that “the failure to provide the plaintiffs with an individualized determination of their own ability to qualify for positions on these teams is, under Reed, violative of the Equal Protection Clause.”Footnote 135 Although the court ultimately argued in favor of the plaintiffs, it carefully specified what this case did not decide.Footnote 136

Because neither high school offered separate teams for Brenden or St. Pierre, the court did not have to rule whether or not schools could fulfill their responsibilities under the Equal Protection Clause by providing separate but equal athletic facilities for females.Footnote 137 Second, because the sports in question were noncontact sports, this case did not decide whether schools could prevent women from competing in contact sports with men.Footnote 138 Third, this case did not require the court to determine whether classifications based on sex were suspect.Footnote 139 As the court noted in Brenden, the High School League’s rule could not be justified even under the standard applied to test nonsuspect classifications. Last, the court granted a permanent injunction, but limited it to the facts presented and applied only to the two plaintiffs. As Wien notes, “The decision in Brenden v Independent School District is limited to a situation wherein plaintiff high school girls wished to take part in certain interscholastic boys’ athletics (tennis, cross-country track and skiing).”Footnote 140 The evidence concerning substantial physiological differences between males and females was, therefore, irrelevant to this case, because the two plaintiffs could, as a matter of skill in these sports, competently compete on the boys’ teams.Footnote 141

The significance of the Brenden case for this study was Judge Heaney’s reference to the activities and opinions of the other branches of government in drawing his conclusion that “at the very least, the plaintiff’s interest in participating in interscholastic sports is a substantial and cognizable one.”Footnote 142 He cited the reports of the President’s Task Force on Women’s Rights and Responsibilities and the President’s Commission on the Status of Women as evidence that discrimination in education had been recognized as an issue of great importance.Footnote 143 He also quoted Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 as illustrative of Congress’s recognition of the importance of sex discrimination in education. Judge Heaney thus quoted the specific words of other policy arenas, thereby illustrating that the three arenas “communicated” with one another to develop policy concerning gender equity in athletics. Indeed, the federal arena resembled an echo chamber on this key subject.

Very quickly, the other branches of government referenced the Brenden decision in their evaluation of Title IX policy. In an exchange between Caspar Weinberger and Robert Dixon Jr., assistant attorney general in the Office of Legal Counsel, in June 1974, Weinberger specifically requested information concerning the “applicability of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 to athletic activities and, in particular, intercollegiate activities.”Footnote 144 In his response, Dixon considered both judicial precedent and legislative history.

The overall purpose of Dixon’s response was twofold: (1) to answer the questions posed by Secretary Weinberger concerning the applicability of Title IX to athletic activities and (2) to argue his department’s opinion on what Title IX regulations should entail. Ultimately, Dixon argued that the rules needed to be more specific concerning athletics: “We recognize the complex and novel nature of the issues presented by the application of Title IX to athletics and the consequent difficulty of drafting a regulation on the subject. Still, in our view, the present provisions on athletics (§ 86.38) are not adequate. We recommend that an effort be made to spell out more clearly what Title IX means with respect to athletics.”Footnote 145 In addition, Title IX’s legislative history seemed to indicate that “Congress, like the courts, embraced the view that an as yet undetermined number of rational distinctions between the sexes in regard to educational and athletic activities may be proper.”Footnote 146 HEW’s Title IX regulations should, therefore, allow some distinctions in athletic activities, such as separate locker rooms for men and women and separation by sex in regard to contact sports.

Dixon specifically referenced Brenden v. Independent School District 742, 477 F.2d (8th Cir. 1973), contending that the interpretation of the court “bolstered” support for a broad interpretation of Title IX and the inclusion of athletics in Title IX coverage. The court ruled that “discrimination in high school interscholastic athletics constitute[d] discrimination in education.”Footnote 147 As Dixon’s letter indicates, the court’s affirmation that Brendan and St. Pierre had been denied their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment “spoke” to the other arenas about judicial opinion concerning sex discrimination in sport.

The emergence of athletics on Title IX’s policy agenda thus occurred simultaneously and serendipitously across all three institutions. At the same time Heaney wrote his opinion concerning gender equity in athletics, the executive branch and Congress debated Title IX regulations with particular concern for athletics. Outside organized forces and the political and social context also supported a focus on gender equity in athletics.

CONCLUSION

After the passage of Title IX in June 1972, several elements and institutional processes came together within a changing social context to expand the statute’s meaning to incorporate gender equity in athletics. Like a “perfect storm” or the rare alignment of the planets, the coming together of historical context, institutional processes, and social elements created the proper timing for agenda shift. Before Congress passed Title IX, in preparation for the regulation-writing process, the Office of Education created a commission to evaluate the impact of OE programs on women. The final report released in November discussed athletics as a part of educational opportunity. In 1973, a window opened in Congress for the clarification of congressional intent on Title IX policy. The expiration of the Educational and Secondary Education Act of 1965 created the opportunity for the passage of the Education Amendments of 1974, which led to hearings on the Women’s Education Equity Act and a statute (the Javits amendment) that clearly indicated athletics as a part of women’s equity in education. Also within the same time frame, the executive arena developed and proposed Title IX regulations. Although not the most salient issue at the time, the question of whether or not revenue-producing sports should be excluded from Title IX regulations emerged as “the single most controversial issue in the Title IX [proposed] regulation based upon public and Congressional interest.”Footnote 148 Policy formulation within the executive arena included reference to the Javits amendment as indication of congressional intent and the need to include reasonable provisions for athletics. The judicial arena also participated in the dialogue as congressional and executive members considered judicial precedent in their debates and the courts referenced congressional and executive activity as it established precedent concerning gender equity in athletics. Athletics thus became a part of Title IX policy in the early 1970s as an issue that appeared simultaneously within a policy community that extended across all three policy-making arenas.

Historical context, unintended consequences, and external factors also contributed to the proper timing for change. Two key players in Title IX’s early development, Bernice Sandler and Margot Polivy, both acknowledged in interviews the importance of timing in its passage; if it had come any later, its passage would have been more difficult. Conflict among outside interests also redirected Title IX’s policy agenda. At the time, women’s groups did not want sports for women as defined by men. But as groups in support of men’s athletics fought so hard against Title IX, it raised political awareness of Title IX’s potential for the women’s groups. This point of contention focused the agenda on Title IX’s impact on athletics, as these groups testified in congressional hearings and wrote letters to congressional and executive members and provided information in the comment period during the regulation-writing process. Institutional processes and political events thus opened the window for policy change, while historical context and interest-group conflict focused the agenda. All together, these factors fostered the right timing for agenda setting and policy change in Title IX to include athletics as a component of gender equity in education.