In the aftermath of the June 2016 EU Referendum result the majority of attention has focused on what might be the future economic relationship between the UK and the EU and the prospects for the UK's trade relationships with third countries once outside the EU. None of the proposed models for the future trade policy relationship between the UK and the EU (for example, membership of the European Economic Area or a Free Trade agreement) come with a defined foreign and security policy relationship. Further, article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, providing for the exit of a member state from the EU, does not offer a roadmap to a new status of foreign, security and defence policy relationship between the EU and its exiting partner.

As a member of the EU, the UK's external relations, extending beyond foreign and security policy, and encompassing a wider variety of areas including trade, aid, environment, energy, development policy, immigration, border, asylum, cross-border policing, justice policies are all currently intertwined with EU policies. Establishing the broad panoply of UK national policies across all of these areas will be an extensive undertaking. This article focuses on the implications of Brexit for the UK's foreign, security and defence policy. Security and defence policy gives effects to the broader foreign policy aims and ambitions for a state. For the UK the EU has been a centrepiece of foreign policy since accession in 1973. Consequently exiting the EU presents the prospect of a major rethink in the aims and ambitions for Britain's place in the world and has implications for the conduct of British diplomacy and will impinge on security and defence policy (Reference WhitmanWhitman, 2016a, b). The British government has yet to outline a coherent assessment of Brexit's implications. As illustrative, neither Prime Minister Theresa May's UN General Assembly address in September nor Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson's 2 October speech to the Conservative Party conference provide sufficient detail on the objectives of future UK foreign policy and so allow for a sufficiently solid basis to assess the country's future stance on security and defence policy (Reference MayMay, 2016; Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2016).

The June Referendum vote can be read as facilitating the acceleration of a trend that was already at work in government thinking. The two recent Conservative-led governments had already sought to re-calibrate Britain's place in the world to ‘de-centre’ the EU from the UK's foreign policy. In a response to the rise of ‘emerging powers’ – as well as to shifts in the global political economy giving a greater prominence to China and Asia – the UK government was already placing greater emphasis on the UK as a ‘networked’ foreign policy actor, for whom the EU is only one network of influence. The current government core strategy documents that guide the UK government's foreign, security and defence policy clearly demonstrate this position. The 2015 National Security Strategy (NSS) and Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) place the EU in a minor supporting role in the UK's defence and security (HM Govt, 2015). Similarly, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office's Single Departmental Plan places the EU in a subordinate rather than a central place in British diplomacy.Footnote 1 Whether it is now appropriate to revise the NSS, SDSR and Departmental Plan should be the subject of policy debate.

As a nation-state with significant diplomatic and military resources, the UK's foreign, security and defence policy has never been solely pursued through the EU but via a variety of institutions (most notably the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the United Nations) and key bilateral relationships, such as that with the United States. Consequently, the detachment of the UK's foreign, security and defence policy from the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) will be less complicated than in other areas of public policy. Furthermore, for the EU the loss of the UK's diplomatic and military resources will diminish the collective capabilities at the disposal of EU foreign and defence policies.

The existing EU-UK foreign, security and defence policy relationship

The EU's current arrangements for collective foreign and security policy, the CFSP and the CSDP, are conducted on an intergovernmental basis. Foreign policy was not a component of the EU's founding treaties and only emerged as an informal process of collective consultation between member states in the early 1970s. Foreign policy coordination was revamped and made a constituent part of the European Union in 1993, with the coming into force of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and creating the CFSP and a commitment to an EU defence policy. The CFSP has the purpose of coordinating the foreign policies of the member states. It remains different from other areas of EU policy as each member state has the ability to veto any collective decision, so policymaking is normally described as intergovernmental, rather than based on the community method of decision-making in which the European Commission proposes policy which is co-legislated by the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament. The EU's High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/Vice President of the European Commission (HR/VP), currently Federica Mogherini, takes the lead in steering the EU's collective foreign policy on behalf of the member states and coordinating this with the EU's other ‘external action’ activity (as it is described in EU-speak), such as trade and development policy. To assist the HR/VP in her role there is the European External Action Service (EEAS). The EEAS is a diplomatic service populated by European civil servants and seconded national diplomats. Whilst based in Brussels, it operates a network of EU delegations (which enjoy a similar status to embassies) in third countries.

The Foreign Affairs Council (FAC), composed of member states' foreign (and sometimes development, defence and trade) ministers meets at least monthly to discuss and take decisions on common foreign policy positions, and to adopt measures, such as sanctions, to give effect to foreign policy decisions.Footnote 2 The FAC is also responsible for taking decisions to launch crisis management activities under the CSDP. As well as chairing the FAC, the HR/VP represents the EU's collective foreign policy positions to third countries and conducts diplomacy on behalf of the member states. These member states appoint ambassadors to a Political and Security Committee (PSC) (chaired by representatives from the EEAS) which provide oversight of the day-to-day operations of the EU's foreign, security and defence policies as well as providing policy options for consideration by the FAC.

The CFSP's achievements to-date remain rather modest and mixed as the European Council on Foreign Relations annual EU Foreign Policy Scorecard illustrates.Footnote 3 Recent successes include the EU's participation in the Iran nuclear diplomacy process and brokering agreement between the Kosovan and Serbian Governments to normalise their relations. Yet these must be set against less positive outcomes in Ukraine, Syria and Libya.

Successive British governments have been largely comfortable with the intergovernmental nature of the CFSP since its creation. The British government has assessed its own participation in the CFSP positively in the Review of the Balance of Competences exercise undertaken under the 2010–15 Coalition government (HM Govt, 2013). The foreign policy report summarised the expert evidence that it received with the assessment that it is “generally strongly in the UK's interests to work through the EU in foreign policy”. Proposals to reform the CFSP – such as introducing qualified majority voting for decision-making – have been made by successive British administrations irrespective of their political composition. Where reforms have been agreed by the CFSP under the Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon Treaties, Britain has held a consistent position in preserving the central role and veto power of member states, resisting the ‘communitisation’ of the CFSP by keeping the European Commission from assuming a leading role in initiating policy proposals, and seeking to improve the effectiveness of the CFSP via greater use of the EU's own financial resources and power as a trading bloc.

The EU embarked on its own defence policy in the early 1990s when the member states collectively agreed to create a common defence policy. The CSDP, like the CFSP, is an area of intergovernmental cooperation between the EU's member states. The CSDP has different ambitions and purposes from the collective defence purpose of NATO. The EU's CSDP focuses on preventing, managing and resolving conflict using both military and civilian resources. These include providing peace-keeping forces, providing security for elections to take place in states in conflict, training police, armed forces and security personnel in third countries, and monitoring disputed borders, ceasefires and peace agreements. The range of roles that the EU and its member states seek to undertake collectively are known as the ‘Petersberg tasks’. Since 2003, over thirty missions have been launched in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Western Balkans, Eastern Europe and the Caucuses.Footnote 4 The CSDP is also intended to enhance the collective capabilities of member state armed forces by coordinating military procurement and enhancing interoperability by developing joint military forces capable of undertaking Petersberg missions.

The UK can lay claim to an early leading role in the development of the CSDP. The EU's ambitions for a defence policy, set out in the TEU, were rather directionless until the 1998 Anglo-French summit in St Malo, where Tony Blair and Jacques Chirac agreed to a push for greater EU defence capabilities. As the EU's two most capable military powers, the UK-French agreement laid the ground for what was to became the EU's CSDP.

Since this time, the UK has shifted from leader to laggard in terms of its support for the development and substantiation of an EU defence policy. Indeed, the CSDP has not been a core component of British security and defence planning over the past decade. The SDSR made no reference to the CSDP as a component of the UK's approach to providing for its national security and defence.

Relative to its size, the UK has been a very modest contributor to the military strand of the CSDP operations (figure 1). It has generally had a preference for commitments through the framework of NATO. In contrast, it has committed personnel to the majority of the EU's ‘civilian’ missions deployed for roles such as border observation and capacity building for third countries. The civilian missions fit readily into the UK's development of the ‘comprehensive approach’ to international conflict management, which brings together diplomacy, defence and development resources to address the problems of failed and failing states. Independent analysts credit the UK with shaping the EU's agenda in this area (Reference PostPost, 2014; Reference Wittkowsky and WittkampfWittkowsky and Wittkampf, 2013).

Figure 1. Number of CSDP missions and designated lead states 2003–16

The main priority for UK defence and security in recent years has been recalibrating strategic choices following the withdrawal of military forces from Iraq and Afghanistan. A key concern has also been the UK's capacity for diplomatic influence and for influencing regional and international security in the context of diminishing public expenditure and the attendant shrinkage of diplomatic and military resources. There has also been a growing caution around overseas intervention due to public and elite scepticism and weariness. This has not, however, led to a greater enthusiasm for burden sharing on defence or the pooling and sharing of military resources with other member states via the EU.

There has, however, been interest in developing bilateral defence relationships with other European countries outside the EU. The UK has invested particularly heavily in its relationship with France in recent years. The 2010 Lancaster House treaties created a new Anglo-French defence relationship rooted in collaboration on nuclear weapons technology and increased interoperability of armed forces. The treaties are premised on closer cooperation between the UK and France to facilitate greater burden-sharing in the EU and NATO. France has persisted with the idea of Anglo-French coordination at the heart of a successful EU foreign, security and defence policy despite the reticence of recent British governments in respect of an EU defence policy. It is not yet clear as to whether Brexit would reduce the tempo of collaboration.

Foreign, security and defence policy after the Referendum vote

For the EU the most immediate impact on the foreign, security and defence policy area has been to give impetus to ideas on reforming EU defence policy which have been in circulation for some time. A set of proposals have been made for deepening the existing defence collaboration between the EU's other member states. However, choosing defence as the area to draw attention to the EU's continuing ability to deepen integration between its member states is a bold but risky move.

It is risky because, despite being a commitment contained in the Maastricht Treaty that came into force in 1993, the achievement of an EU defence and security policy has been modest to date. The CSDP has developed by undertaking a series of civilian and military conflict management missions. These have been unexceptional both in terms of their size and the military capabilities required to undertaken the missions. The EU has created the 1,500 strong stand-by Battlegroups (composed of rotating member state armed forces) to have the capability to intervene swiftly for the purposes of managing or stabilising conflicts. These have never been deployed.

A group of member states remains nervous about the EU developing its defence capabilities. This is either because of domestic public opposition to deepening EU defence, for example in the Irish Republic, or because of concern, expressed publicly by the Baltic states, that the EU should not complicate NATO's role in European security. The latter concern has been somewhat mitigated by the agreement signed between the EU and NATO to broaden and deepen their relationship at NATO's Warsaw Summit in July 2016.Footnote 5

A key reason why defence is an attractive area to focus upon is because the UK has vetoed modest proposals for the development of the CSDP. The UK has shifted from being a leader, in the late 1990s, in the development of an EU defence policy to being a much less enthusiastic participant in recent years. The UK has not been willing to engage at a level of significant scale and scope with CSDP military operations. In addition, it has been resistant to proposals to further develop the role of the European Defence Agency (EDA). The UK has also vetoed the creation of a permanent military EU operational headquarters (OHQ) which is supported by a significant proportion of the EU member states.

The new initiatives that have been proposed on EU defence are primarily the revival of these proposals. Germany and France are the key players in this initiative. The two governments' ideas have been crystallised into a six-page position paper.Footnote 6 The Franco-German proposals provide further impetus to ideas contained within the EU's new Global Strategy,Footnote 7 unveiled by the EU's High Representative following the UK's referendum, to further develop defence collaboration between the EU's member states.

The Franco-German proposals contain components which do represent a significant departure from the current EU defence arrangements. The first is to create a permanent OHQ. This is to give the EU a greater capacity for the command and control of military missions. Currently the EU uses operational headquarters ‘borrowed’ from the EU's member states (including the UK) or from NATO. The creation of such an arrangement has been mooted for some time but been a proposition that UK governments have firmly resisted. Franco-German paper would also give the EU the command centre capacity for coordinating medical assistance, a logistics centre for sharing ‘strategic’ assets, such as air-lift capacities, and sharing satellite reconnaissance data.

The second is its call for a common budget for military research and for the joint procurement of capabilities such as air-lift, satellite, cyber-defence assets and surveillance drones – all to run under the auspices of the EDA. A further idea is that there should be a ramping up of military force capabilities available to the EU by using the existing Battlegroups and utilising the Eurocorps which already brings together Germany, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy and Poland in a combined force.

To overcome differences of view on the future for EU defence that exist between the 27 member states, the proposal is to utilise the currently unused ‘permanent structured cooperation’ provisions of the EU treaties that allow for smaller groups of EU member states to undertake deeper defence collaboration even if all member states do not wish to participate.

European Commission President Mr Junker's ‘State of the Union’ address on 14 September demonstrates that thinking in Brussels is aligned with the proposals coming from Berlin and Paris.Footnote 8 His speech urged the creation of a single operational headquarters, to create common military assets (which would be EU-owned), and the creation of a budget for defence capabilities (a European Defence Fund) to boost research and innovation. Junker also made reference to permanent structured cooperation as a vehicle for deeper collaboration.

The push for a select group of like-minded EU countries to deepen their defence collaboration has quickly taken root. The Italian government has proposed an even more ambitious proposal that its Defence Minister, Roberta Pinotti, called a “Schengen for Defence”.Footnote 9 The proposal here is to mimic the development of the Schengen travel area which was created outside the EU Treaties by a small group of countries, progressively widened to others and then imported wholesale into the EU. Here the idea is to create a division-sized European Multinational Force able to act collectively under a unified command, with permanent forces in place and with a common budget to fund its operations. If not quite a proposal to create a dedicated European army, the Italian proposal, if ever implemented, would be the largest and most ambitious European defence integration development since the foundation of NATO in 1949.

The British government's immediate response to these proposals has been to threaten their enactment while the UK is still a member of the EU.Footnote 10 Such a short-term tactic, however, is not a replacement for consideration as to what would be best for the long-term interests of the UK. As with other policy areas, the UK government will need to determine how it envisages national foreign, security and defence policy engaging with the EU's own policies in these areas.

The relatively under-developed and intergovernmental nature of the CSDP does mean that the impact for the UK in departing from the EU's existing policy in this area would be marginal. The UK would, however, have a greatly diminished capacity for shaping the future agenda for EU defence policy and, as indicated above, EU policy may develop in a direction that the UK views as contrary to its interests.

Exiting the EU's CFSP would appear to carry more significant costs for the UK. The CFSP currently provides significant efficiencies for the UK in addressing a wide range of foreign policy and security issues, via a multilateral format, with 27 other European countries. It allows the UK to amplify national foreign and security policy interests by having these translated into collective positions held by 28 countries.

The CFSP decision-making mechanisms allow the UK to resolve inter-state disagreements, and to iron out differences behind closed doors before pursuing collective positions on issues of common concern – often before they reach international forums. As an illustration, the current collective EU sanctions regime towards Russia, following its occupation of Crimea and military involvement in Eastern Ukraine, provides an example of where significantly divergent views between the Member States were directed into strong collective action that was the UK's preferred policy. Leaving the EU and exiting the CFSP decision-making structures would see the UK looking to influence policy from outside. This would be a far more complicated and time consuming undertaking than at present. And crucially, the UK would also formally lose its ability to veto the development of policy in areas that it would see as contrary to its interests.

The future for the UK-EU foreign, security and defence policy relationship

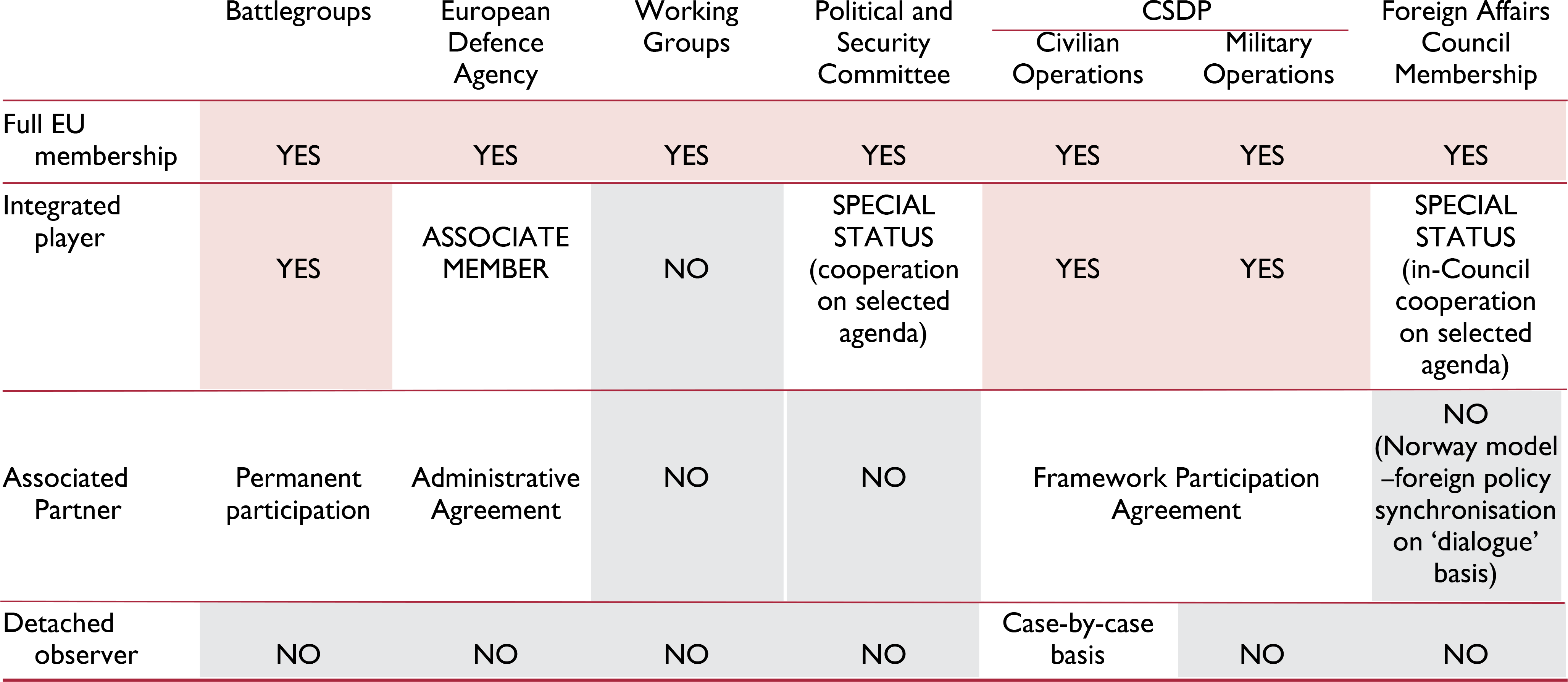

In embarking on the process of exiting the EU, the UK's future arrangements for cooperation in the areas of foreign, security and defence policy will need to be negotiated. Both the UK and the EU and its member states will need to take a view as to the characteristics of their future framework for cooperation. The UK will need to determine the degree to which it wishes to seek autonomy from the EU in foreign and security policymaking processes and the extent to which it might envisage national policies diverging from the portfolio of existing EU policies. Three alternative scenarios of the future foreign, security and defence relationship between the UK and the EU might be envisaged: integrated player, associated partner, detached observer.

Integrated player

At present the EU preserves a foreign policy decision-making system which keeps non-member states outside the mechanisms of decision-making. In leaving the EU the UK would no longer be a participant in the Foreign Affairs Council, the European Council, Political and Security Committee, its working groups and the secure COREU communications network. The UK would also depart the collaboration arrangements between member states in third country capitals and centres of multilateral diplomacy such as New York and Geneva.

Yet, the UK could still participate, via a special status, in the work of the EU's foreign and security policy-making infrastructure in the form of an EU+1 arrangement for example. This would allow for participation in the Foreign Affairs Council for relevant agenda items and (with the precedent for participation by the US Secretary of State and UN Secretary General), the work of the PSC and its working groups. The UK's foreign policy would remain largely in correspondence with the EU's portfolio of foreign security and defence policy.

On the CSDP the UK might engage a ‘reverse Denmark’ where it would remain outside the EU but inside the CSDP. The UK would continue with its existing commitments to current CSDP military and civilian operations, and participate in equal terms in future missions. It would also preserve its existing commitment to provide the EU with a Battlegroup and to remain on the roster of Battlegroups available for deployment. The UK could also hold associate membership status of the European Defence Agency (EDA), participate in projects on the current case-by-case basis, be granted observer status on the Agency's Steering Board and make a contribution to the EDA budget. Under this arrangement the UK's diplomatic capacity and military capabilities would be integrated with the EU's foreign and security policy to mutual benefit.

Figure 2. Future scenarios for UK and EU relationships in the areas of CFSP and CSDP

Associated partner

A looser relationship to EU foreign and security policy would be to replicate the relationship that already exists between the EU and Norway. This would constitute an arrangement in which the UK would align itself with EU foreign policy declarations and actions, such as sanctions, at the invitation of the EU. Exchanges on foreign policy issues would be on a ‘dialogue’ basis at ministerial, director and working-group level rather than allowing for direct participation in policymaking.

The UK would remain outside the EU's structures of military planning but may decide to participate in aspects of implementation. This could involve the signing of a Framework Participation Agreement (FPA) to allow for participation in CSDP operations on a case-by-case basis. The UK could also decide to sign an administrative agreement with the European Defence Agency (EDA) allowing for its participation in EDA initiatives but it would lose the ability to determine the strategy of the Agency. The UK might also want to consider ongoing permanent participation in an EU Battlegroup, as is currently the case with Norway.

Under an Associated Partner model the UK would relinquish its capacity to have direct influence on the development of EU foreign, security and defence policy but seek to involve itself with EU activity as an adjunct to a preference for a predominantly UK-centric outlook.

Detached observer

Under this model the United Kingdom remains politically and organisationally separated from the EU's foreign and security policies. This is not to suggest that the UK might see its foreign policy run counter to that of EU member states but, rather, makes a determination that it wishes to preserve a formally disconnected position vis-à-vis EU foreign and security policies. The UK may have preference for privileging bilateral relationships with EU member states and use this as the primary route for influencing EU foreign and security policy, rather than seek to influence through existing EU third party arrangements. This would provide the UK with the greatest degree of autonomy from, but possibly lowest level of influence on, EU foreign and security policy.

In the CSDP area the UK may decide to follow the practice of the United States. The US has not participated in the EU's military CSDP missions but has participated in civilian CSDP missions on a case-by-case basis via a framework agreement on crisis management operations signed in 2011. The UK may decide to replicate the US in working in separate missions alongside, rather than being integrated into, EU military deployments.

The relationship between the UK and EU may be one of largely corresponding positions on foreign and security policy issues – but also with the possibility of divergence in some issue areas. Whether divergence might develop into competition between the EU and the UK in third party relationships may be dependent on trade-offs that the UK may wish to make in privileging deepening economic ties with third countries over other issues.

Conclusion

Current UK debate on Brexit has focused on the timetable for triggering the negotiations for the UK's EU exit and the alternative forms of trading relationships that might be developed. None of the existing relationships that the EU has with a third country or a group of states – such as the EEA or free trade models – encompasses the embedded nature of the relationship between the EU's and UK's politics and societies that has developed since 1973. As the Brexit negotiations proceed, a wider range of issues will be up for consideration.

As an alternative to the current membership relationship the EU and the UK will most likely establish a broadranging ‘final status’ partnership agreement which reflects their ongoing economic, security and political interdependence. It would represent a new style of relationship made by the EU, and might also provide a future model for relations with neighbouring states such as Turkey as an alternative arrangement to EU membership.

The key components of the EU-UK partnership will key issues beyond markets and encompass a security relationship. Shared borders and a common neighbourhood will dictate the need for working in partnership. Security – the foreign, security and defence policy component of the relationship – should represent the most straightforward aspect of the future EU-UK relationship that is to be negotiated. Its key benefit is that it would ensure that the UK's diplomatic and military capabilities are broadly aligned with the EU's external action and allow for synchronised policy and action.

The key question for the UK and the EU during the Brexit negotiations in the security area is the degree to which both sides seek a relationship that sees the UK integrated into existing EU decision-making and collective implementation. For the UK it is also the degree to which it wishes to establish greater autonomy for divergence from the existing portfolio of EU policies. As this article suggests, there are costs and benefits in differing scenarios for the future foreign, security and defence policy relationships between the UK and the EU.