There is strong evidence to suggest that substantial health and economic benefits follow from improved nutrition in early life(1–4) and that breast-feeding is beneficial for both mother and baby(3). Breast-feeding protects against infection and morbidity, promotes development of the infant immune system(Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros5) and may support neurological development(Reference Brion, Lawlor and Matijasevich6,Reference Horta, Loret de Mola and Victora7) . It facilitates maternal postpartum weight normalisation(Reference Baker, Gamborg and Heitmann8), with persistent benefits for maintaining a healthy BMI(Reference Bobrow, Quigley and Green9) and reduces the risk of breast cancer(10) and endometriosis(Reference Farland, Eliassen and Tamimi11). The WHO recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of life, with continuation alongside complementary feeding to 2 years or beyond(Reference Kramer and Kakuma12,13) , and this advice is mirrored by national health organisations(3,14–16) and expert bodies(17–Reference Fewtrell, Bronsky and Campoy19). Because of the well-established benefits of breast-feeding to mother and baby, continuous promotion, education and assessment of infant feeding are vital, particularly in areas that traditionally have a low prevalence of breast-feeding.

Worldwide, many countries fail to meet breast-feeding recommendations, and the WHO European region is reported to have the lowest rates of breast-feeding(20). The European Perinatal Health Report 2010, with data from nineteen countries, showed that while more than 95 % of mothers in the Czech Republic, Switzerland, Latvia, Portugal and Slovenia breastfed to some extent in early life, early breast-feeding rates were below 70 % in Ireland, France, Scotland, Malta and Cyprus(21). National infant feeding surveys in Ireland, the UK and Scotland have reported low rates of breast-feeding in the first 6 months(Reference Layte and McCrory22–24), and current Health Service estimates suggest that in England 46 % breastfeed to any extent at 6–8 weeks(25). In Northern Ireland, 25 % breastfeed at 6 weeks, 20 % at 3 months and 13 % at 6 months(Reference Purdy, McAvoy and Cotter26). In Ireland, the latest national figures, from 2015 to 2016, indicate that 60 % of mothers breastfeed to any extent at hospital discharge, with 10 % of these feeding a combination of breast milk and infant formula(27). Post-discharge, national data are collected at 3 months postpartum only; 42 % of women are reported to breastfeed to any extent at this time(28). Despite the continuing low prevalence of breast-feeding, secular data do suggest some improvement in breast-feeding rates in Ireland and the UK over the past decade(24,27) , although the effect of methodological and population changes on national data challenges direct comparability across time(Reference Brick and Nolan29). In our previous birth cohort (participants recruited 2008–2011), we found higher breast-feeding initiation rates than nationally reported, but low levels of breast-feeding continuation(Reference O’Donovan, Murray and Hourihane30).

Because it has one of the lowest rates of breast-feeding initiation, as well as high rates of early breast-feeding cessation(Reference Layte and McCrory22), data from Ireland can provide a useful case study to inform the design and implementation of targeted breast-feeding policies and supports. However, detailed data are lacking. This paper describes early milk feeding data collected over the first 9 months of life in a nutrition-focused, longitudinal, prospective birth cohort study, the Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort (COMBINE). Using research midwife-administered questionnaires and in-person interviews at six time-points over the 9-month period, we aimed to describe infant milk feeding practices in detail and to examine the prevalence and impact of combination feeding of breast milk and infant formula on breast-feeding duration.

Methods

Study design

The COMBINE study, based in Cork, Ireland, is a longitudinal, prospective birth cohort study from early pregnancy to 24 months of age. Participants of the Improved Pregnancy Outcomes via Early Detection study (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; trial ID: NCT01891240) formed the recruitment pool for COMBINE. Improved Pregnancy Outcomes via Early Detection participants were generally healthy, low-risk, nulliparous women with a singleton pregnancy, who attended antenatal care at Cork University Maternity Hospital(Reference Navaratnam, Alfirevic and Baker31). Recruitment for COMBINE commenced in late 2015 and finished in late 2017, and 903 Improved Pregnancy Outcomes via Early Detection participants were eligible for postnatal follow-up in COMBINE during this period. After exclusion of twelve infants who met the newborn exclusion criteria (admitted to neonatal intensive care unit for >2 weeks or had a severe metabolic or genomic anomaly requiring ongoing specialist care in the neonatal period), 456 mother–infant pairs were recruited and participated in postnatal follow-up in COMBINE. Research midwives conducted nine study visits with families over the first 24 months of the baby’s life; the present analysis focuses on the first 9 months. Following delivery, the first follow-up visit was conducted in the maternity hospital and subsequent visits were scheduled for 1 month, 2, 4, 6 and 9 months (online Supplementary Fig. S1).

COMBINE was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the University College Cork Clinical Research Ethics Committee (ECM4(hh)06/01/15 and ECM3(bbb)10/04/18). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study is registered at http://www.birthcohorts.net/.

Raw data from the Cork Babies After SCOPE: Evaluating the Longitudinal Impact using Neurological and Nutritional Endpoints (BASELINE) birth cohort study were used to investigate changes in feeding patterns over the last 8–10 years. Briefly, between 2008 and 2011, the BASELINE study recruited 2137 maternal–infant dyads, who attended antenatal care at Cork University Maternity Hospital(Reference O’Donovan, Murray and Hourihane32). The study design, methods and data collection were similar in BASELINE and COMBINE, and in BASELINE, postnatal follow-up used for this analysis was at hospital discharge, 2 and 6 months. BASELINE was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (ECM 5 (9) 01/07/2008).

Data collection and preparation

In COMBINE, all feeding data were collected through interviewer-led questionnaires. At hospital discharge, simple infant feeding data were collected to ascertain the infant feeding method. At subsequent study visits, more in-depth information on feeding methods and practices were collected, with the questionnaires designed through past experience and literature review. Key questions included if the participant was breast, infant formula or combination feeding. If the participant reported breast-feeding only, data on use of infant formula top-ups since last visit were collected. Participants were asked if they had given their baby any fluids other than breast milk or infant formula and if so, the fluid given was recorded. Consistency of data across study visits was routinely monitored. If a participant ceased breast-feeding between visits, infant age at cessation (in weeks) was recorded and participants were asked to provide their reason(s) for breast-feeding cessation in their own words. This was matched to a predefined list of common reasons for breast-feeding cessation, and the match with the participant’s original answer was clarified with the participant to confirm. If an answer not on the predefined list was provided, it was recorded as ‘other’ and an open text box used to record the specific reason for breast-feeding cessation. If a participant reported combination feeding breast milk and infant formula, a similar approach was taken to ascertain their reason(s) for doing so.

Feeding in the first 9 months of life was analysed both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. In this analysis, breast-feeding refers to breast milk as the main milk source, although the infant may have received occasional formula top-ups, and combination feeding describes feeding both breast milk and formula as routine. Any breast-feeding encompasses both breast-feeding (breast milk as main milk source) and combination feeding. Infant formula feeding is defined as giving formula only, with no breast milk. These terms allow inclusion of supplementary fluids, as well as solid foods and do not differentiate between direct and expressed breast-feeding.

In addition, longitudinal exclusive and predominant breast-feeding as defined by the WHO(33) is reported from birth to each visit up to 6 months. These variables were prepared to account for use of any formula (including top-ups), supplementary fluids or solid foods at a preceding time, as appropriate to each definition (see Table 1). The WHO exclusive and predominant breast-feeding definitions do not preclude the use of medicines, vitamins or minerals and do not differentiate between direct and expressed breast-feeding.

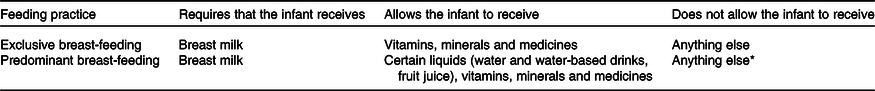

Table 1. Exclusive and predominant breast-feeding definitions according to the WHO(33)

* In particular infant formula.

Statistical analysis

Data collected during the study were stored in a bespoke, centralised, internet-deployed database (MedSciNet), which facilitates data entry, tracking and multi-step review. Data were then exported to Excel® 2016 (Microsoft), and statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS® version 24.0 (IBM Corp.) software for Windows™. Normality testing indicated that descriptive and feeding data were non-parametric, and data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), with categorical data presented as percentage (%). χ 2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used, as appropriate, in comparisons of categorical variables between participant groups. Differences in continuous variables were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Simple relative risk ratios for combination feeding and breast-feeding cessation were calculated as (Probability of breast-feeding cessation in combination feeding participants)/(Probability of breast-feeding cessation in breast-feeding solely participants)(Reference Tenny and Hoffman34). Statistical significance is defined at P < 0·05.

Results

Maternal and infant characteristics

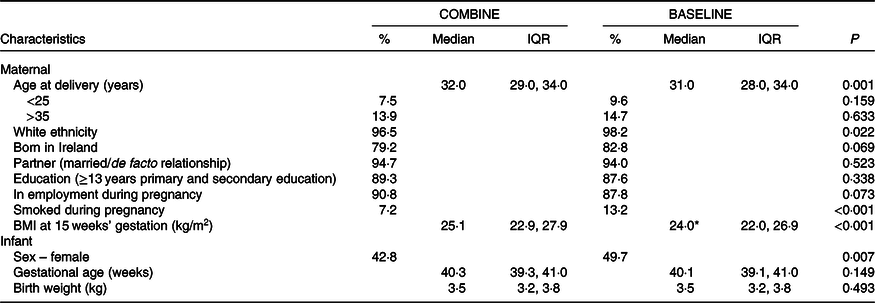

Characteristics of participants of the COMBINE study (n 456) are presented in Table 2. Median maternal age at delivery was 32 (IQR 29, 34) years. While 8 % of participants were <25 years, 14 % were >35 years of age. There was a high proportion of white (97 %) and Irish-born (79 %) mothers in the cohort. Most participants were in a stable relationship (95 %), in employment (91 %) and had a third-level qualification (75 %). Median gestational age and birth weight were 40 (IQR 39, 41) weeks and 3·5 (IQR 3·2, 3·8) kg, respectively, and the rate of neonatal unit admittance was 15 %. As shown in online Supplementary Fig. S1, 92 % of recruited participants completed the 1-month study visit, 86 % the 2-month, 80 % the 4-month, 79 % the 6-month and 76 % completed the 9-month study visits. Mothers who left the study before the 9-month visit were less likely to be in a stable relationship (89 v. 96 %, P = 0·006) compared with those who completed the study to 9 months, but there were no other demographic differences, including in tertiary education (64 v. 76 %, P = 0·17) or the proportion born in Ireland (75 v. 81 %, P = 0·20), between those who dropped-out and completed the study. The median age of mothers who did not complete the study was 30 (IQR 25, 33) years, compared with 33 (IQR 30, 35) years in mothers who continued in the study to 9 months, P < 0·001.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants in the Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort (COMBINE; n 456, recruited 2015–2017) and BASELINE (n 2137, recruited 2008–2011) birth cohort studies

(Percentages; medians and interquartile ranges (IQR))

BASELINE, Babies After SCOPE: Evaluating the Longitudinal Impact using Neurological and Nutritional Endpoints.

* n 1436.

Infant milk feeding practices

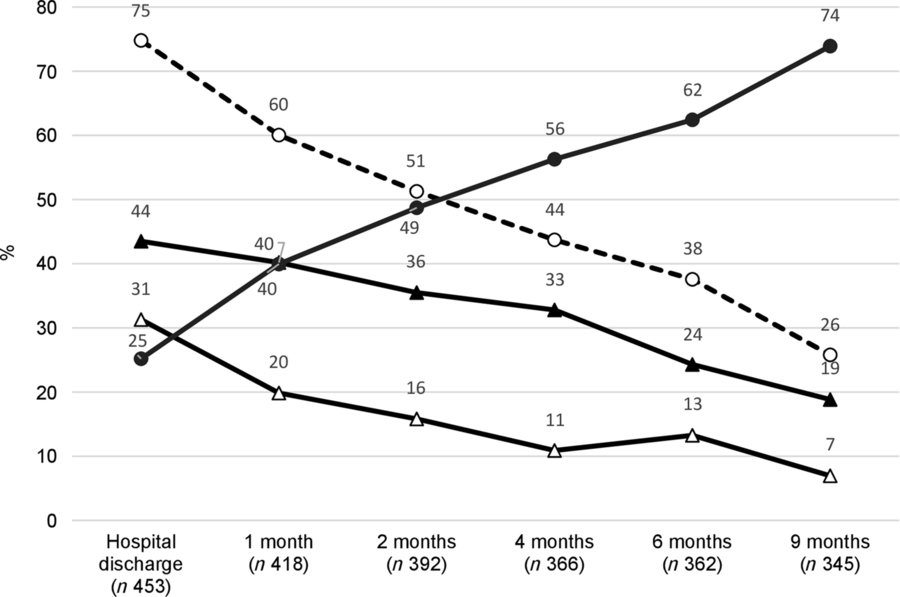

Fig. 1 details infant milk feeding practices at six time points over the first 9 months. At hospital discharge, 75 % of mothers provided any breast milk (breast or combination fed) and this decreased to 60 % by 1 month. Just over half (51 %) and a quarter (26 %) of the cohort breastfed to any extent at 2 and 9 months, respectively.

Fig. 1. Infant milk feeding patterns in the first 9 months of life in the Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort. Any breast-feeding (![]() ): breast-feeding and combination feeding. Breast-feeding (

): breast-feeding and combination feeding. Breast-feeding (![]() ): breast milk as the main milk source. Combination feeding (

): breast milk as the main milk source. Combination feeding (![]() ): both breast milk and infant formula on a daily basis. Infant formula feeding (

): both breast milk and infant formula on a daily basis. Infant formula feeding (![]() ): formula only (no breast milk).

): formula only (no breast milk).

At hospital discharge, 44 % of mothers breastfed as the main milk source, which decreased to 40 % by the 1-month follow-up visit and continued to decline to 24 % at 6 months and 19 % at 9 months. One-third (31 %) combination fed both breast milk and formula at discharge and one-fifth (20 %) did so at 1 month. Combination feeding halved to 11 % between 1 and 4 months and fluctuated slightly thereafter (13 and 7 % at 6 and 9 months, respectively). The prevalence of infant formula feeding increased throughout the study; 25 % of mothers formula fed at hospital discharge and 49 % did so at the 2 month follow-up. By 9 months, 74 % provided formula as the main milk source.

Breast-feeding patterns

Women who breastfed to any extent at hospital discharge were slightly older (33 (IQR 30, 35) v. 31 (IQR 27, 34) years, P < 0·001) and less likely to be <25 years old at delivery (4 v. 18 %, P < 0·001), born in Ireland (75 v. 91 %, P < 0·001) and of white ethnicity (95 v. 100 %, P = 0·016) than those who never breastfed. A higher proportion had a third-level qualification (84 v. 49 %, P < 0·001) and were in a stable relationship (97 v. 90 %, P = 0·004). Among breast-feeding mothers, 29 % had given at least one formula top-up between hospital discharge and 1 month and the equivalent figures were 14, 19 and 9 % in the intervals between 1–2 months, 2–4 months and 4–6 months, respectively. Most reported infrequent formula top-ups; at each time point, 45–63 % had not given infant formula more than three times since the previous visit.

Of the three quarters of mothers who breastfed to any extent at discharge, 20 % did so for <1 month, 25 % for 1–4 months, 9 % for 4–6 months, 14 % for 6–9 months and 32 % were still breast-feeding at 9 months. Among those who stopped breast-feeding within the 9-month study period, the median infant age at cessation was 7 (IQR 2, 22) weeks and 26 % stopped breast-feeding within the first 2 weeks. There were many reasons for breast-feeding cessation (online Supplementary Table S1). The most common reason given was an insufficient milk supply (perceived/actual) or failure to thrive (27 %); these mothers stopped breast-feeding earlier than those who gave alternative reasons for cessation of breast-feeding (6 (IQR 2, 10) v. 11 (IQR 3, 26) weeks, P = 0·005).

Exclusive and predominant breast-feeding

Longitudinal exclusive and predominant breast-feeding practices from birth to 6 months are presented in Fig. 2. Exclusive and predominant breast-feeding was not differentiated at hospital discharge. At discharge, 40 % of participants had exclusively breastfed since birth and 22 % continued to breastfeed exclusively to 1 month. Participants who exclusively breastfed to hospital discharge but not 1 month lost exclusive breast-feeding status through the use of water or other supplementary fluids (48 %), at least one formula top-up (22 %), initiation of combination feeding (33 %) and/or cessation of breast-feeding (30 %). The rate of exclusive breast-feeding to 2 months was 18 %, and 15 % exclusively breastfed from birth to 4 months. Whilst 38 % of infants were receiving breast milk at 6 months, only 1·9 % (six mothers) breastfed exclusively to this time point. All participants (n 42) who lost exclusive breast-feeding status between 4 and 6 months initiated complementary feeding during this time, although all were still breast-feeding to some extent at 6 months. Online Supplementary Table S2 details use of supplementary fluids in the cohort.

Fig. 2. Longitudinal breast-feeding practices in the Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort showing the percentage of participants predominantly and exclusively breast-feeding according to WHO definitions(33) from birth to 6 months. Predominant breast-feeding (![]() ): the infant may have received water or other liquids but no infant formula or solid foods. Exclusive breast-feeding (

): the infant may have received water or other liquids but no infant formula or solid foods. Exclusive breast-feeding (![]() ): breast milk only, with no formula, other liquids or solid foods. Any breast-feeding (

): breast milk only, with no formula, other liquids or solid foods. Any breast-feeding (![]() ): breast and combination feeding. † Exclusive and predominant breast-feeding were not differentiated at hospital discharge.

): breast and combination feeding. † Exclusive and predominant breast-feeding were not differentiated at hospital discharge.

Rates of predominant breast-feeding (infant may have received water or other supplementary fluids but not infant formula) were slightly higher than exclusive breast-feeding at 1, 2 and 4 months, at 29, 21 and 18 %, respectively. In those who had predominantly breastfed, water was the most commonly given liquid, but inappropriate fluids, including herbal teas, were also used.

Combination feeding patterns

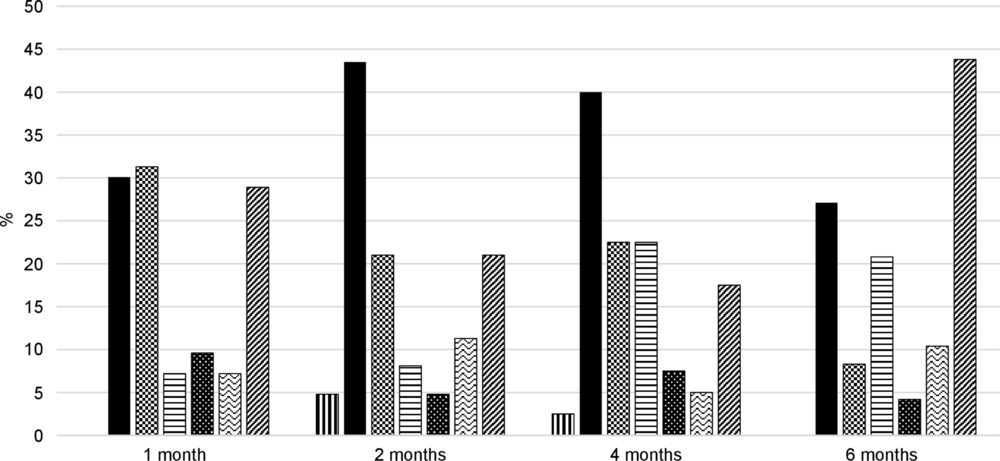

Between 7 and 31 % of participants reported feeding both breast milk and infant formula on a daily basis during the study (Fig. 1). Although the reasons for combination feeding varied over time (Fig. 3), a concern that baby was hungry was commonly expressed (30, 43, 40 and 27 % at 1, 2, 4 and 6 months, respectively). Up to 4 months, between 21 and 31 % of participants reported receiving advice from a healthcare professional to combination feed. At each visit, 13–17 % reported sleep-related reasons (infant sleeps better or sharing burden of night feeds) for giving infant formula as well as breast milk. While 7 % reported inclusion of family members as a reason for combination feeding at 1 month, this increased to 21 % at 6 months. Other reasons for combination feeding at 1 month included low breast milk supply/latching difficulties (13 %) and maternal pain/illness (7 %), as well as initiation of infant formula use in the neonatal unit with continuation on discharge (5 %). At 6 months, weaning (19 %) and return to work (15 %) were commonly cited as other reasons for using infant formula. Embarrassment at breast-feeding in public was not commonly reported at any visit (0–5 %).

Fig. 3. Reasons for combination feeding in the Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort. Participants may have provided more than one reason for combination feeding breast milk and infant formula. ![]() , Embarrassed to feed in public;

, Embarrassed to feed in public; ![]() , concern baby is hungry;

, concern baby is hungry; ![]() , healthcare professional advice;

, healthcare professional advice; ![]() , include family;

, include family; ![]() , sleeps better;

, sleeps better; ![]() , share burden;

, share burden; ![]() , other.

, other.

Combination feeding and breast-feeding continuation

As shown in Fig. 4, successful breast-feeding was associated with continuation of breast-feeding; at every visit, those who breastfed were significantly more likely than those who combination fed to be giving any breast milk at the next visit (all P < 0·001). Of mothers who were breast-feeding at hospital discharge, 86 % breastfed to any extent at 1 month, compared with 68 % of those who were combination feeding on discharge (P < 0·001). This translates to a relative risk of breast-feeding cessation by 1 month of 2·3 in those combination feeding at hospital discharge, as compared with those breast-feeding solely. In terms of breast-feeding duration, in participants who ceased breast-feeding during the study, the duration of breast-feeding was halved in those who combination fed at discharge compared with those who breastfed (median 6 (IQR 2, 19) v. 12 (IQR 4, 26) weeks, P = 0·006).

Fig. 4. Percentage of participants in the Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort receiving any breast milk at each follow-up visit according to whether they were breastfed (![]() ) or combination fed (

) or combination fed (![]() ) at the previous visit. For example, 86 % of infants who were breastfed at discharge received breast milk at 1 month and 68 % of infants who were combination fed at discharge received breast milk at 1 month. Differences were assessed using Pearson χ 2, *P < 0·001.

) at the previous visit. For example, 86 % of infants who were breastfed at discharge received breast milk at 1 month and 68 % of infants who were combination fed at discharge received breast milk at 1 month. Differences were assessed using Pearson χ 2, *P < 0·001.

Substantial differences were also observed at later visits. For example, 95 % of mothers who breastfed as the main milk source at 4 months breastfed to any extent at 6 months (P < 0·001) v. 53 % of those who were combination feeding. The rate of any breast-feeding at 9 months was 89 % in those who breastfed at 6 months, compared with 33 % in those who combination fed (P < 0·001). The relative risk for breast-feeding cessation if combination feeding, as compared with breast-feeding solely, was 12·0 between 1 and 2 months, 14·7 between 2 and 4 months, 9·1 between 4 and 6 months and 6·3 between 6 and 9 months.

Changes in feeding patterns over time

To investigate changes in milk feeding patterns over the last decade, differences in feeding practices between the BASELINE (recruited 2008–2011) and COMBINE (recruited 2015–2017) studies were examined. As shown in Table 2, participants in the recent COMBINE cohort were slightly older than participants in earlier BASELINE cohort (32 (29, 34) v. 31 (28, 34) years, P = 0·001), although there were no differences in the proportion of participants <25 or >35 years of age between the two cohorts (both P > 0·05). A slightly higher proportion of participants in the earlier cohort were of white ethnicity (98 v. 97 %, P = 0·042) and smoked during pregnancy (13 v. 7 %, P < 0·001), compared with participants in the recent cohort, but other maternal demographic characteristics did not differ (all P > 0·05). At hospital discharge, 75 % of participants in the recent COMBINE cohort breastfed to any extent, compared with 69 % in the earlier BASELINE cohort (P = 0·011), and the proportion giving any breast milk remained higher in COMBINE at 2 (51 v. 44 %, P = 0·009) and 6 (38 v. 23 %, P < 0·001) months. While rates of combination feeding were similar at each time point (all P > 0·05), a higher percentage of mothers breastfed as the main milk source in the recent COMBINE cohort than the earlier BASELINE cohort at 2 (36 v. 27 %, P = 0·01) and 6 (24 v. 12 %, P < 0·001) months, with no significant difference at hospital discharge (44 v. 40 %, P = 0·25) (Fig. 5). There was a consistently lower prevalence of formula feeding in the more recent cohort than the earlier cohort; 25 v. 31 % at hospital discharge (P = 0·011), 49 v. 55 % at 2 months (P = 0·009) and 62 v. 77 % at 6 months (P < 0·001).

Fig. 5. Percentage of participants in the COMBINE (![]() ; recruited 2015–2017) and BASELINE (

; recruited 2015–2017) and BASELINE (![]() ; recruited 2008–2011) studies who were breast-feeding (breast milk as main milk source) at hospital discharge, 2 months and 6 months. Differences were assessed using Pearson χ 2, *P < 0·05. COMBINE, Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort; BASELINE, Babies After SCOPE: Evaluating the Longitudinal Impact using Neurological and Nutritional Endpoints.

; recruited 2008–2011) studies who were breast-feeding (breast milk as main milk source) at hospital discharge, 2 months and 6 months. Differences were assessed using Pearson χ 2, *P < 0·05. COMBINE, Cork Nutrition and Development Maternal-Infant Cohort; BASELINE, Babies After SCOPE: Evaluating the Longitudinal Impact using Neurological and Nutritional Endpoints.

Discussion

We have presented a detailed description of early infant feeding practices in a large and well-characterised prospective cohort study in Ireland, which has a history of low breast-feeding rates. Through multiple closely timed follow-ups, we identified frequent changes in feeding methods over the first months of life and showed that precise breast-feeding definitions are required to accurately capture feeding patterns. High rates of early breast-feeding cessation persist; one-quarter of women who ceased breast-feeding did so within 2 weeks. Women who fed a combination of breast milk and infant formula were less likely to continue breast-feeding than those who fed breast milk only. This is highly relevant given that a substantial proportion of mothers used combination feeding during the first month.

The most recent national report in Ireland suggests that 60 % of mothers breastfeed to any extent at hospital discharge, with 50 % breast-feeding solely(27). There was a higher rate of any breast-feeding in this cohort (75 %), but a smaller proportion were breast-feeding solely (44 %). The higher rate of any breast-feeding may be reflective of study demographics, but potential differences in data collection and specification of feeding methods challenge direct comparisons. Nationally collected data are not as rigorously specified, which may account for the lower proportion of women breast-feeding solely in the cohort despite a higher rate of any breast-feeding.

Recognising that early breast-feeding cessation is a major challenge, infant feeding policies increasingly target improvements in breast-feeding duration(35–37). Collectively, national data highlight low rates of breast-feeding continuation through the first months of life(Reference Layte and McCrory22–Reference Purdy, McAvoy and Cotter26,28) , but can be limited in the time points examined, by the use of retrospective recall and through a lack of standardised and specific feeding definitions. Our data show that the most substantial drop in any breast-feeding occurred between discharge and 1 month, with continuing decreases thereafter. Almost half of participants who breastfed at discharge did so for <4 months, and given that one quarter of those who stopped breast-feeding during the study did so within the first 2 weeks of birth, the problem of early cessation, despite a relatively high prevalence of breast-feeding initiation, appears to be a critical one from the point of view of breast-feeding support service provision.

Support from healthcare professionals, as well as maternal satisfaction with support, predict breast-feeding continuation(Reference Tarrant, Younger and Sheridan-Pereira38) and a mother’s own experience is the most influential factor to continuation(Reference Begley, Gallagher and Clarke39). Thus, directing resources towards early feeding support and overcoming initial difficulties, thereby increasing maternal understanding and confidence, may prove most beneficial to improving breast-feeding duration. In addition to healthcare professionals, formal and informal peer and family support can positively influence breast-feeding duration(Reference Tarrant, Younger and Sheridan-Pereira40,Reference McFadden, Gavine and Renfrew41) . Because breast-feeding intention prior to birth influences breast-feeding initiation and continuation(Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows23), antenatal breast-feeding support is also essential, particularly in population groups with lower breast-feeding initiation rates, such as young, lower educated or lower socio-economic groups(Reference Layte and McCrory22).

The practice of combination feeding breast milk and infant formula was common, particularly in the postpartum period, and at every study visit, women who combination fed were more likely to cease breast-feeding. Given this, the reasons provided for combination feeding are of interest. Data on the reasons for combination feeding in hospital were not available, but other studies have reported reduced breast-feeding duration and increased likelihood of cessation, irrespective of the reason for in-hospital infant formula use(Reference Chantry, Dewey and Peerson42,Reference Agboado, Michel and Jackson43) .

From 1 month on, concern that baby was hungry, indicating an insufficient milk supply, was commonly cited as a reason for combination feeding. Studies suggest that perceived milk insufficiency can relate to factors such as breast-feeding self-efficacy, confidence, support and knowledge(Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Buccini and Segura-Pérez44,Reference Galipeau, Dumas and Lepage45) , rather than actual milk insufficiency. Although common infant behaviours, crying, fretfulness, discontentment and unsettledness, as well as changes in feeding pattern, frequency or duration may be interpreted as hunger signals and thus perceived as indicators of milk insufficiency(Reference Kent, Hepworth and Sherriff46–Reference Gatti48). While not precisely known, the prevalence of biological milk insufficiency, where enough milk cannot be produced to satiate the infant, is thought to be low(Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Buccini and Segura-Pérez44). However, quantifying actual milk production, through measurement of breast milk transfer, is challenging and not routinely practised in clinical settings(Reference Boss, Gardner and Hartmann49). Infant growth can be tracked as a proxy indicator of milk sufficiency and will identify cases of growth faltering, where combination feeding may be medically indicated. In this regard, exploration of the relationship between maternal reported milk insufficiency and infant growth is of interest. Where there is no evidence of growth faltering and breast-feeding continuation is deemed appropriate, adequate resourcing and support systems should facilitate mothers to continue breast-feeding without the use of infant formula, should they choose to do so.

In Scotland, a 10–11 % increase in any breast-feeding at 4 and 6 months between 2010 and 2017 has been reported, with no change in initiation rate(24). National data in Ireland suggest an increase in the proportion who breastfed to some extent at discharge between 2010 and 2016 (54–60 %)(27), and although only collected for the first time in 2015, an increase in any breast-feeding at 3 months between 2015 and 2019 (34–42 %)(28,50) . However, caution may be warranted due to the well-established and potentially substantial effects of changing demographics(Reference Brick and Nolan29). Conducted in the same maternity hospital, using similar methods, the COMBINE (recruited 2015–2017) and BASELINE (recruited 2008–2011) birth cohorts provide a useful backdrop from which to examine trends in feeding over an 8–10 year period. The proportion who breastfed solely in COMBINE was 1·3-fold higher at 2 months and 2-fold higher at 6 months, indicating an increase in breast-feeding duration over this time frame, with little change in initiation. Participants in COMBINE had additional study visits at 1 and 4 months and, although strictly an observational cohort, were afforded the opportunity to discuss any queries they had with research staff at each visit, which could have influenced breast-feeding rates at subsequent visits. However, the magnitude of the increases is neither likely attributable to the two additional study visits nor the 1-year increase in median maternal age and 1 % increase in non-white ethnicity.

Participant demographics, including the high proportion of white mothers, are largely reflective of the Irish population and that of many European countries, but this cohort was not designed to be nationally representative. All participants were nulliparous, increasing uniformity but potentially limiting generalisability. Nulliparous women may experience breast-feeding differently to multiparous women, being more likely to experience early difficulties and report cessation due to latching problems and milk insufficiency(Reference Hackman, Schaefer and Beiler51). Successfully breast-feeding a first child may potentiate breast-feeding of subsequent children(Reference Bai, Fong and Tarrant52,Reference Holowko, Jones and Koupil53) . In the UK and Ireland, where there is a high incidence of early cessation, particularly due to reported breast-feeding difficulties, this may discourage mothers from breast-feeding in subsequent pregnancies, leading to a negative effect of multiparity(Reference Layte and McCrory22,Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows23) . Enabling successful breast-feeding experiences in nulliparous women may therefore prove most effective in increasing breast-feeding rates.

A common challenge of longitudinal cohort research is participant retention, particularly with frequent study visits(Reference Teague, Youssef and Macdonald54). Although COMBINE had a relatively high retention rate, mothers who left the study early were younger and less likely to be in a stable relationship than those who completed the study, which may limit generalisability of results to young or single mothers. Given the potential for bias if selective attrition of younger, lower socio-economic or minority groups occurs(Reference Nunan, Aronson and Bankhead55) and possible socio-demographic differences in infant feeding patterns, future studies could implement tailored retention strategies toward particular groups. In interpretation of results, the possibility of an ecological fallacy should be considered; aggregate data at the cohort level may not apply at the individual level(Reference Sedgwick56).

This work is strengthened by description of infant feeding practices according to a number of precise definitions. Although the WHO indicators for exclusive and predominant breast-feeding are often based on 24- or 48-h recalls, we have reported them on a continuum since birth, as in the 2010 UK Infant Feeding Survey(Reference McAndrew, Thompson and Fellows23), because use of infant formula top-ups and other fluids, which is common in the current context, will introduce bias and may substantially overestimate the true rate of exclusive/predominant breast-feeding. Reported breast-feeding rates can depend greatly on the definition used. For example, the rate of any breast-feeding, an aggregate of feeding patterns, was 7–31 % higher than that of breast-feeding solely at each visit. At 6 months, the rate of any breast-feeding was 14-fold higher than WHO-defined exclusive breast-feeding from birth. Although often reported, the rate of any breast-feeding can be misleading, depending on the context of the feeding practices, and because of a decreased likelihood of breast-feeding continuation and potential dose–response effects of breast-feeding(3,Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros5) , distinguishing those who feed both breast milk and infant formula is pertinent. Clear, specific and standardised definitions of feeding patterns are essential for future population and epidemiological studies to ensure accuracy in collected statistics, comparability and usability of data, and we echo calls for the development of robust and consistent definitions of infant feeding to provide a core indicator set for use at local, national and international level(Reference Whitford, Hoddinott and Amir57).

Through a well-characterised, prospective birth cohort, with frequent, closely timed follow-up visits and precisely specified breast-feeding definitions, we have provided an analysis of current early infant milk feeding practices in Ireland. The rate of early breast-feeding cessation, particularly in the first weeks post-partum, remains very high, and we identified that mothers who combination fed breast milk and infant formula were more likely to subsequently cease breast-feeding than mothers breast-feeding solely. Given this, and an increased breast-feeding duration in the past 8–10 years in mothers who do successfully establish breast-feeding, the first weeks may be a critical window of opportunity for breast-feeding support services. The acknowledged importance of breast-feeding and its myriad benefits mean that this should be prioritised as a public health intervention.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the families and research teams of the COMBINE and BASELINE birth cohort studies for their participation and support.

This work was funded through a grant from Science Foundation Ireland to MEK for the COMBINE project (grant no. INFANT/B3067), which is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund under Ireland’s European Structural and Investment Funds Programmes 2014–2020. Science Foundation Ireland had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. The Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study was funded by the National Children’s Research Centre, Ireland; the National Children’s Research Centre had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

M. E. K. designed the COMBINE cohort study and is Principal Investigator, A. H. and M. E. K. formulated the research questions, D. F. conducted COMBINE study visits, E. D. and D. M. M. provided clinical advice and governance, A. H. and T. B. conducted quality control and constructed the database, A. H. analysed the data, prepared and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520001324