INTRODUCTION

The Franco-Scottish calligrapher and writer Esther Inglis has mainly been studied for her skill with pen and needle, and her political associations via her husband. Closer examination reveals an even more interesting and unusual woman, part of the international cultural landscape at the time. Inglis created at least twenty-five self-portraits in the sixty or so of her manuscript books currently known to survive. An attempt to classify these into portrait types was first made by A. H. Scott-Elliot and Elspeth Yeo in their seminal catalogue of Inglis's manuscripts, published in 1990.Footnote 1 Since then, several scholars, including myself, have written about the portraits while considering the broader implications of Inglis's work.Footnote 2 No one, however, has focused entirely on the portraits in an attempt to contextualize them within the overlapping margins of print, manuscript, and paint cultures in which she worked as a female limner and calligrapher. Many of the texts she reproduced in numerous calligraphic hands were taken from printed books; others she composed herself. Her exquisitely detailed self-portraits showing her as a writer draw from the print tradition of author portraits, which she recycles back into manuscript culture. At the same time, many of her later colored portraits draw on the art of limning as practiced by such artists as Nicholas Hilliard (ca. 1547–1619) and Isaac Oliver (ca. 1565–1617).

As a creative woman and religious refugee, Inglis crossed boundaries of gender, language, and nationality to work in a transcultural community. The Scottish society in which she lived was multilingual, with strong cross-fertilization of ideas through Continental travel and importation of books. She herself wrote in French- and Scots-inflected English, and very likely knew Latin as well. This study considers the overriding Protestant ethos behind her work and places it within a broader European context, examining portraits of French women writers and Italian women artists; printed books; painted miniatures; and the art of calligraphy.

THE SELF-PORTRAIT IN A CALVINIST CONTEXT

The idea of the self in the Renaissance has been extensively debated. As early as 1860, the historian Jacob Burkhardt wrote that the concept of an individual self began in Italy in the fourteenth century, thus generating a historical cliché that has been difficult to shake, but has been questioned and revised by many others, not least Stephen Greenblatt in his influential book Renaissance Self-Fashioning (1980). Borrowing theoretical ideas from anthropologist Clifford Geertz, Greenblatt investigated what he called the self-fashioning of six middle-class male writers, focusing on how they fashioned a self “in relation to something perceived as alien, strange, or hostile.” Here, human identity was constructed through the individual's transactions with the “Other,” and with “authority,” either of which might take on multiple meanings, while the transactions themselves were seen as a struggle.Footnote 3 This theory was quickly adopted by a range of literary scholars, but eventually it was criticized for being (among other things) not only elitist but also sexist, with scholars of feminist and queer studies quickly demanding a place at the table. Those studying early modern women in particular first adopted a self-fashioning approach that read much of women's writings as expressions of feminist negotiation with an oppressive patriarchy—a stance that, in addition to anachronistically reading modern feminist desires onto historical women, created a restrictive lens for viewing the past. Most scholars today have moved beyond that earlier phase, broadening their investigations to include the materiality of objects and bodies, as well as considerations of the natural world, race, class, and transnationalism.

Turning to Esther Inglis and her self-portraits, it is useful to refocus on the social matrix in which she thrived. Rather than assuming that she is daring when she shows her work and represents an image of herself to counter some masculine oppressive view of women, I suggest that she identifies herself creatively within—not against—the communities and spaces of which she is a part: geographic place and family, her Huguenot religion, the Scottish humanist circle, and artistic craftsmanship.

Inglis was born in Dieppe while her parents were in the process of fleeing to Britain as religious refugees. After spending a few years in London, they went on to Scotland in 1574, where she lived most of her life, except for the years between 1604 and 1615 when she moved with her husband to London and Essex. In some of her earliest manuscripts, she refers to herself as “daughter of Dieppe,” and “Esther English, Frenchwoman” (the latter lettered on the frame around early self-portraits), reflecting “her sense of solidarity with her suffering protestant correligionists in France.”Footnote 4 She thus begins her work from the liminal position of an outsider and insider; her identity is largely centered on the Huguenot exile community and her family, who have crossed geographical boundaries in order to survive. Furthermore, she marks her continued movement from Scotland to England with the movement of her Scottish countrymen following James VI (1566–1625) to London, and then back again, noting in almost all of her manuscripts the date and place of their composition, ranging from “Lislebourg en Ecosse” (Edinburgh), to London, Mortlake, Willingale Spain (Essex, place of her husband's benefice), and returning finally to “Edenbrough,” circling back to where she began her work and where she would die.

Amid these travels and changing circumstances, an unshakable constant was her commitment to her faith. Inglis was always first and foremost a Calvinist, a member of that church that believed in the reprobacy of human beings and their works. This faith was expressed by the religious motto she adopts in many of her ink self-portraits: “From the Eternal, goodness: From myself, evil, or nothing,” as well as her own short poems, “Prayer to God” in six early manuscripts, and “To the reader” in two, and most obviously in the biblical and religious poetic contents of all the manuscripts.Footnote 5 Overlapping with, and indeed part of, the Scottish Calvinist community was the circle of Scottish humanists with whom Inglis identified and who were personal friends: men such as Andrew Melville (1545–1622), John Johnston (ca. 1570–1611), and Robert Rollock (ca. 1555–99). The first, who had spent years in France and in John Calvin's (1509–64) Geneva, was a leading and controversial ideologue of the presbyterian movement within the Scottish Kirk. A prolific poet and reformer of university education, Melville was principal first of Glasgow University, then of St. Mary's College, St. Andrews. Robert Rollock taught at St. Andrews, before becoming the first principal of Edinburgh's new Tounis College, and John Johnston was another internationally traveled scholar who taught theology at St. Mary's from around 1595. All three men produced epigrams dedicated to Inglis, which she appends to many of her self-portraits. Sarah Gwyneth Ross identifies Inglis as a member of what she terms “the transnational elite of learned women,” and shows how Melville and Johnston in particular present her “as an ‘intellectual artist’ of their own stamp.” They praise the work of her mind and hand—mens et manus—using the same terminology that they employ in their encomia for each other, thus implicitly accepting her into this Calvinist humanist circle.Footnote 6

Among the Latin liminary verses praising Inglis are six by Andrew Melville, one in particular that she repeats beneath the pen-and-ink self-portraits attached to her black-and-white manuscripts in 1602, and again in 1624: “If I have mind and you have your skilfull hand.”Footnote 7 In this poem he says that her right hand defeats his mind, for her mind can depict the hand, and her hand can depict what is in the mind. Melville is obviously familiar with and playing on the relationship between mind and hand promulgated in humanistic discussions based on the writings of Leonardo (1452–1519), Michelangelo (1475–1564), Vasari (1511–74), and others. As Joanna Woods-Marsden has observed, Antonio Pisano (1395–ca. 1455) had used the term docta manus (learned hand), and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) believed that “the hand was to be understood as an extension of the mind.” He elaborated on this in his 1450 treatise, De Pictura (Of painting), where his objective “was to ‘instruct the painter how he can represent with his hand [mano] what he has understood with his talent [ingenio].’”Footnote 8 By placing this reference to the power of her hand and intellect beneath her self-portrait, Inglis is affirming her position as a genuine artist, skilled both in handwriting and in depicting, or, as she says, “limming.”

Negotiating these often overlapping spaces of geography, family, religion, humanism, and artistic talent helped Inglis to define her position as a woman writer and artist. But the creation of a self-portrait in ink and paint, rather than merely words, took her a step farther in representing who she was. As far as is known, no other European woman writer at the time had attempted such a thing, and the fact that she did so within a strict Calvinist environment may seem even stranger. Scholars have shown, however, that of all forms of art, portraits were the most acceptable to the early Reformers because they represented not “those mysteries that are beyond sensory perception,” but, to quote Calvin, “those things which the eyes are capable of seeing.”Footnote 9 Calvin felt that artistic talent was a gift from God, and portraits of himself and other reformers circulated as means of commemoration and emulation.Footnote 10

Though there were painted portraits, prints were more widely disseminated, one of the major examples being the collection of Icones (Images) (1580) made by Théodore de Bèze (1519–1605), the pastor, writer, and guiding force of world Calvinism, as Calvin's long-lived successor in Geneva. First published in Latin, Icones came out the following year (1581) in an expanded French translation, Les vrais pourtraits des hommes illustres en piete et doctrine (True portraits of men illustrious in devotion and doctrine). Inglis likely knew this collection, not least because it was dedicated to James VI of Scotland and would have circulated there. In his dedication, Bèze faces head-on the risk that some of his audience might oppose the use of images. He writes that “portraiture, sculpture and other such sciences which can be turned to good use, are not to be condemned in themselves.” Good and wise persons, after death, can continue to communicate familiarly with us through books, and likewise through their true portraits we can contemplate them and talk with those whose presence was honorable while they lived.Footnote 11 Bèze's collection contains only one portrait of a woman, Marguerite de Valois (1492–1549), queen of Navarre, the writer and sister of François I (1494–1547). She was sympathetic to the Protestant cause. An independent engraved portrait of Jeanne d'Albret (1528–72), later queen of Navarre, was circulating around the same time. Furthermore, in 1567 the engraver Pierre Woeiriot (1532–ca. 1596) made a portrait of writer Georgette de Montenay (ca. 1540–81), which would be inserted in copies of her Emblemes, ou devises chrestiennes (Emblems or Christian devices, 1567), a book which had a major influence on Esther Inglis. Models of pious Protestant women writers were thus available to Inglis as another resource for developing her self-presentation.

INTRODUCING HER SELF-PORTRAITS

Esther Inglis learned calligraphy from her mother, Marie Presot (d. after 1614), and both likely taught handwriting at the French School in Edinburgh, run by Inglis's father, Nicolas Langlois (d. 1611).Footnote 12 Inglis did not begin adding a self-portrait to her manuscripts until 1599; her first extant manuscript, made in 1586 when she was about sixteen, is a sample of five handwriting styles that she had learned. Even her first presentation manuscript, made in 1591 for Elizabeth I (1533–1603), does not include a self-portrait. Her marriage to Bartilmo Kello (1563–1631) around that time, however, provided a new opening for her talents. Soon afterwards, Kello sought, perhaps successfully, to take charge of the official foreign correspondence of King James VI, making sure it would be properly written and accounted for. The warrant (which may have been drafted by Kello himself, with help from his wife) says that Kello “wreat or cause al the sadis lettiris be his direction be wreatin be the mest exquisit wreater within this Realme,” which has been taken to refer to Inglis.Footnote 13

Around this time in 1599 Inglis began creating some of her most beautifully written manuscripts from her early period, working in black or brown ink on paper.Footnote 14 They include elaborate introductory matter—coats of arms, dedications—and a full-page self-portrait showing her writing at her desk, with lengthy commendatory verses beneath. Scott-Elliot and Yeo identify these as Type 1 among her portraits. These manuscripts were dedicated to Queen Elizabeth, Sir Anthony Bacon (1558–1601), Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (1565–1601), and Prince Maurice of Nassau (1567–1625)—all associated with the Protestant cause.Footnote 15 Kello himself was working with Bacon and Essex on secret negotiations to ensure that James VI would succeed Elizabeth to the English throne.Footnote 16 Evidently Inglis's manuscripts were used to sweeten the pot; a letter from Kello to the queen mentions that the manuscript of Psalms “wreaten be my wyfe in french and in divers sortis of Carectaris . . . wes verre acceptable to your Ma[jes]tie,” while he reminds her that he still needs remuneration.Footnote 17 Gift-giving would also have been part of the reciprocal arrangement between Kello and his employers, Bacon and Essex. Inglis mentions the “good offices” Bacon has done for her husband in her dedication.Footnote 18

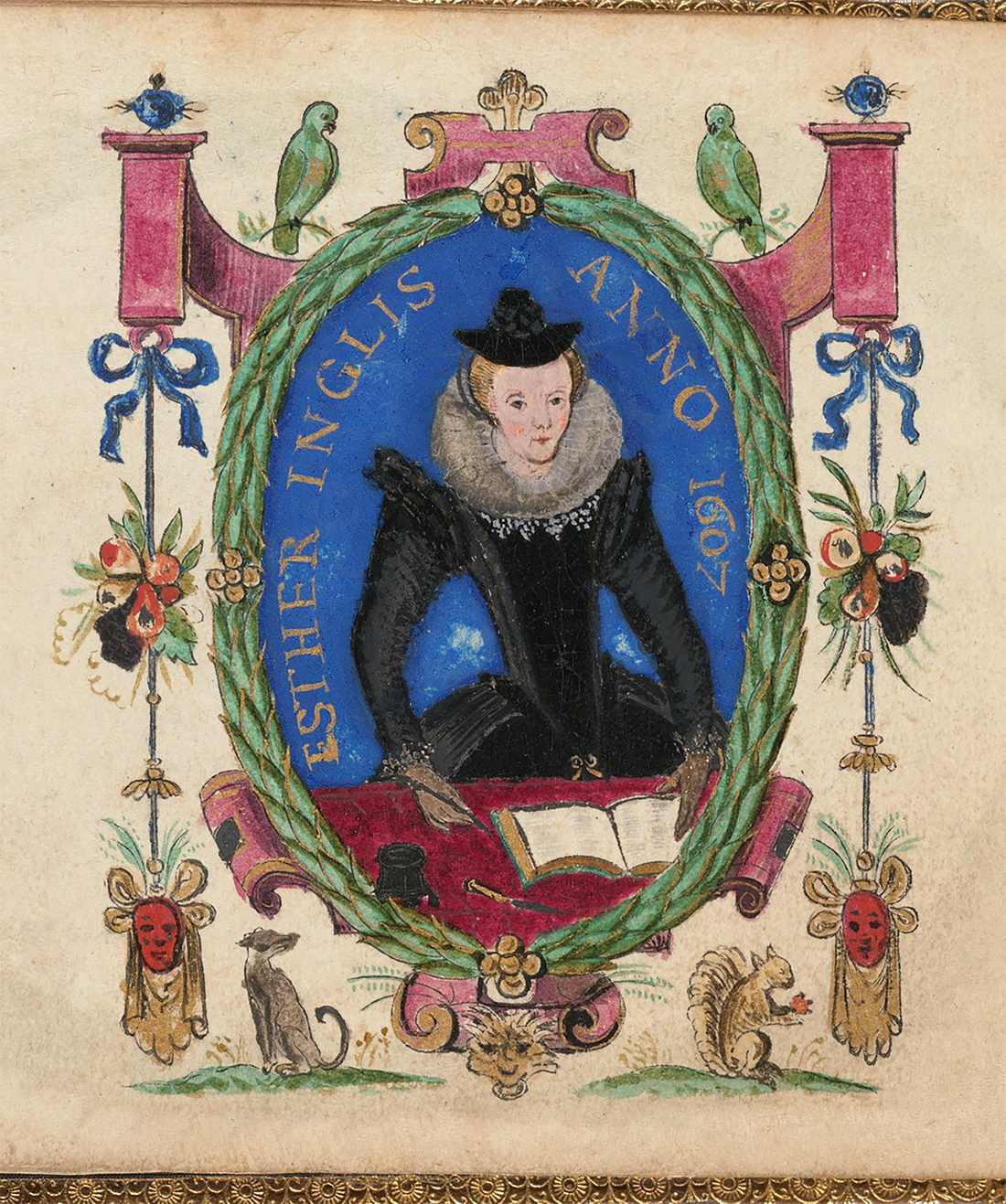

Around 1606, Inglis began using color in her manuscripts, including the self-portraits.Footnote 19 The iconography of these, nominated Type 2, is similar to the black-and-white ones, showing a three-quarter view of Inglis at a desk with writing implements, but now she is poised against a dark blue background, and is surrounded by a brightly colored frame of architectural motifs, fruit, and animals. Two of the most beautiful of these appear in manuscripts presented to Sir Thomas Egerton (1540–1617) in 1606 and Prince Henry (1594–1612) in 1607.Footnote 20 Inglis would have expected remuneration for these elaborate manuscripts, especially for those that were New Year's gifts.Footnote 21

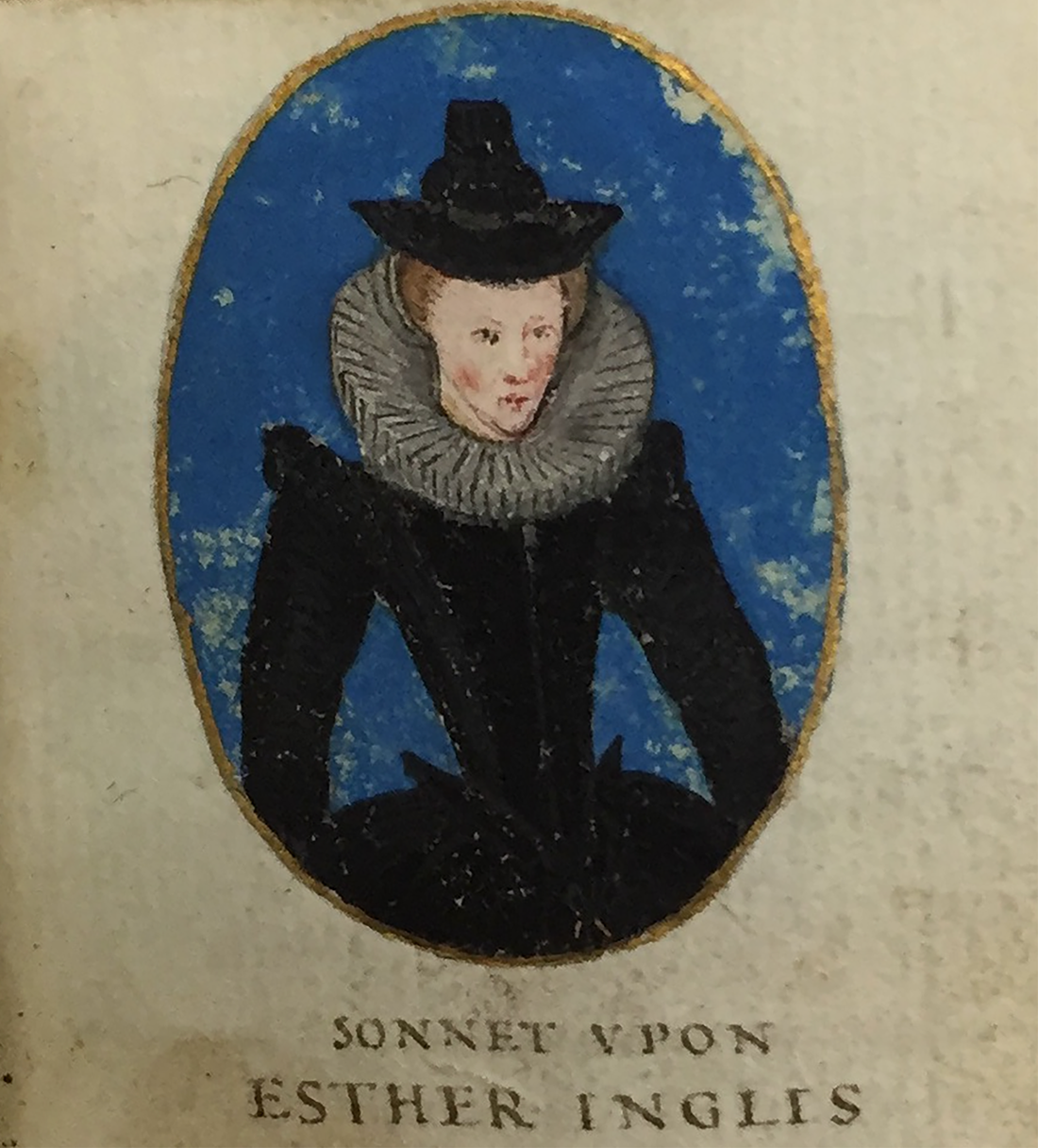

The third type of self-portrait, also in color, shows a three-quarter view of Inglis against a blue background, but her hands, writing instruments, and desk are no longer depicted. Two of these manuscripts were presented to Prince Henry and King James in 1612 and 1615 respectively.Footnote 22 Beginning around 1609, however, and until 1617, Inglis also used a pared-down iconography showing only her head and shoulders against a blue background. Some of those Type 3 portraits were likely cut down from larger versions, while others may have been made in this format; some were painted separately, then cut out and pasted into the manuscripts.Footnote 23

The fourth type is again in black-and-white; Inglis sits at a desk with a pen raised in her right hand, and an ink pot and paper in front of her.Footnote 24 The oval is framed with a leafy or balls-and-bead wreath. Scott-Elliot and Yeo note that these all date to 1624, the year of her death. There are four known examples of manuscripts using this Type 4 portrait, three of which were presented to Prince Charles (1600–49). I shall return to a more detailed examination of the iconography of these portraits after looking at the tradition of visual representations of women writing.

HOW SHOULD A WOMAN WRITER LOOK?

There are few visual depictions of women writing, rather than just holding a book, in the early Western manuscript tradition. In one of the earliest, dating from about 1152, Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) is shown writing on wax tablets.Footnote 25 Although Hildegard's agency has been debated, Madeline Caviness proposes that “some core of the images is based on lost designs that Hildegard devised as she composed the text” from her visions.Footnote 26

The first secular woman depicted as writing is Marie de France (ca. 1160–1215). Although she lived just slightly after Hildegard and wrote mainly in the twelfth century, “there are no extant manuscripts of her writing that date before the thirteenth century.”Footnote 27 Marie consciously thought of herself as a writer and translator. At the end of her Fables she says: “To end these tales I've here narrated / And into Romance tongue translated, / I'll give my name, for memory: / I am from France, my name's Marie.”Footnote 28

Such a claim to authorship, which was also a claim to authority, was relatively new at the time, and practically unheard of among women. It is echoed several centuries later in the title pages of some of Esther Inglis's manuscripts, with inscriptions such as this one in four of her 1599 works, playing wittily on her name and identity: “Written in diverse sorts of letters by Esther English Frenchwoman.”Footnote 29 Here and elsewhere, Inglis highlights her calligraphic skill as well as her identity, and often includes a self-portrait.

Perhaps the most famous depiction of Marie de France writing occurs in a gathering of French medieval verse, “dedicated to Marie of Brabant.”Footnote 30 In the image at the beginning of her Fables she sits at a raised writing desk with manuscript folios spread in front of her (fig. 1). Attached to the desk on the right is an ink horn; in her left hand she holds a scraper and in her right a pen. Susan Ward notes that it is unique among manuscripts of Marie's Fables in setting an image of Marie writing at the beginning of the text, replacing the usual image of Aesop.Footnote 31 Although none of the images of Marie are self-portraits, they reveal the power of Marie's written insistence on her authorship, and their details help establish the iconography of subsequent self-portrayals of women writers and artists for centuries to come.

Figure 1. Portrait of Marie de France, ca. 1300. Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsénal MS 3142, fol. 256r (detail). By permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

About two hundred years after Marie, Christine de Pizan (ca. 1364–ca. 1430) not only wrote a substantial corpus of poetry but also supervised its transcription by scribes, engaged in copying herself, and “personally directed the copying and the decoration of her works as well as the illustration.”Footnote 32 Based on Christine's intense interaction with the production of her own work, Hindman calls her “France's first woman ‘publisher’ as well as its first woman of letters.”Footnote 33 A sumptuous manuscript of her collected works presented to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, dating from 1410–15, “was entirely written by Christine, who also supervised its production,”Footnote 34 making it likely that she had oversight of how she herself was depicted. In addition to two illuminations showing Christine presenting her manuscript to Queen Isabeau and Louis of Orleans, this manuscript also contains the most famous image of Christine at her desk, iconographically similar to the one of Marie, but with the addition of a little dog sitting patiently at her feet (fig. 2). Its prominent position on folio 4r, immediately following her dedication to Queen Isabeau and introducing the first of her works in the collection, Ballades, places Christine emphatically as the author of her manuscript.

Figure 2. Portrait of Christine de Pizan, ca. 1410–ca. 1414. London, British Library, Harleian MS 4431, fol. 4r (detail). © British Library Board.

Inglis would not have seen any of these early French manuscripts, but they do help to establish the iconographic tradition of the woman writer. She might have come across some of Christine's writings in one of the early English, or more likely French printed editions.Footnote 35 Many French books were available in Scotland where, by the later sixteenth century, there were at least five booksellers active in Edinburgh, including Thomas Vautrollier, a Huguenot refugee like the Langlois family.Footnote 36 It is certainly possible, then, that Inglis could have known at least some of Christine's work, though without the illuminations.Footnote 37

Where Inglis did come into contact with Christine was through a work she definitely knew, the Emblemes Chrestiennes by Georgette de Montenay. First published in 1567, then withdrawn because of the religious civil wars and reissued in 1571, Montenay's Protestant emblem book was the first of its kind.Footnote 38 Montenay dedicated her book to Jeanne d'Albret, queen of Navarre and staunch Calvinist, whom Montenay knew. The first emblem shows Jeanne as a wise woman building the city of God, based on the image of the lady building a virtuous city from Christine de Pizan's City of Ladies.

Esther Inglis made her own version of Montenay's emblem book as a gift to Prince Charles in 1624, reworking the first emblem to represent Charles's sister, Elizabeth of Bohemia (1596–1662), who with her husband Frederick I, king of Bohemia (1596–1632) was fighting for the Protestant cause on the Continent.Footnote 39 It is clear, however, that Inglis knew Montenay's book long before 1624.Footnote 40 Her earliest self-portraits show knowledge of the engraved portrait of Georgette de Montenay that was made by Pierre Woeiriot, probably in 1566 when he could have visited her in Paris.Footnote 41 It is evident that Montenay had a say in how she wanted to be depicted, and her portrait helped reinvent the iconography of showing a female writer in print.

THE PRINTED AUTHOR PORTRAIT AS MODEL

As far as I have found, Woeiriot's portrait of Montenay is the first in print in France or England to show a recognizable woman writer. In 1539, Denis Janot printed Hélisenne de Crenne's (1510–ca. 1560) Epistres familières (Familiar letters) with a woodcut showing a woman sitting at a desk and writing, but it is not a portrait. He used the same woodcut in 1541 in his printing of her Songe de madame Helisenne (Dream of Madame Helisenne), evidently as part of his enterprise to create female authorship as “a market niche.”Footnote 42 Marguerite de Navarre was the mother of Jeanne d'Albret. Marguerite's writings were circulated in manuscript and print, but she is not shown putting pen to paper. She helped design the illuminations for the manuscripts of La Coche ou le débat de l'amour (The coach or the debate of love, 1540–41), which depict her as a participant in her own stories, and La Coche is the only one of her works to be fully illustrated in her first printed collection (Lyon, 1547).Footnote 43 While she is recognizable in the manuscript, she is merely represented by a generic female figure in the woodcuts. The well-known engraving (also by Woeiriot, dated 1555) depicting poet Louise Labé (ca. 1523–66) does not show her writing, and may in fact be another woman altogether.Footnote 44

Although the prototype of the secular woman writer at her desk with pen and ink appeared in the manuscripts of Marie de France and Christine de Pizan, when Christine's works reached print in early sixteenth-century France and England, the depictions of her fall between what Martha Driver has called “everywoman” and a full-blown portrait study.Footnote 45 The title page of Le Noir's 1503 Paris edition of Le tresor de la cite des dames (The treasure of the city of ladies) shows a generic woman in a garden outside a city (fig. 3). Henry Pepwell's 1521 edition of the same book in London includes the woodcut of a woman in her study (fig. 4). Neither is an actual portrait of Christine.

Figure 3. Christine de Pizan, Le tresor de la cite des dames, title page, Paris, 1503. Paris, BNF, RES-Y2-746. By permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 4. Christine de Pizan, The boke of the cyte of ladyes, frontispiece, [Aaiv], London, 1521. STC 7271. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

When Montenay and Woeiriot consulted about how she wanted to be presented in her emblem book, they were probably not thinking of the manuscripts depicting Marie de France and Christine de Pizan at their desks, or of the early woodcut figures of women writers, but more likely of the tradition of portraits of male authors. These date to ancient manuscript iconography showing the four Evangelists, often with pen in hand, poring over their books. While such figures were still shown in the woodcuts of sixteenth-century Bibles, that prototype did not completely inform later depictions of contemporary authors.

In her essay on author portraits in sixteenth-century France, Ruth Mortimer shows how the concept of depicting the author in printed books dates back to the late fifteenth century and is based upon the manuscript tradition of allegorical representations of the author with a book, or the author as presenter of (usually) his work to a patron. Probably the earliest printed self-portrait of an author is that of mathematician Oronce Fine (1494–1555), which he designed for the Paris 1532 edition of his Protomathesis (Foundations of mathematics). He depicts himself not writing but holding his book.Footnote 46 A few years later there appeared one of the earliest portraits of an author—Nicolas Bourbon (1503–50)—holding a pen and writing. The woodcut, printed in the 1536 Lyon edition of his Paidagogeion (On the education of the young), is based on a 1535 drawing by Hans Holbein (1460–1524) taken from life.Footnote 47 The early humanists exchanged portraits of themselves in paintings, medallions, or prints. One of the most famous is the 1536 engraving of Erasmus (1466–1536), whom Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) shows sitting at a raised desk, inkpot in left hand, pen in right, with his books at hand. In English books, the “first verisimilar author portrait” is of John Bale (1495–1563), in the 1548 edition of his Comedy Concerning Three Laws.Footnote 48 Bale is only holding a book, but in 1569, James Peele is depicted on the title page to his Pathewaye to Perfectnes sitting in his study, writing in a book at his desk with pen in hand, other writing equipment and books strewn around.

Montenay and Woeiriot could have been influenced by such images or by one closer to home: that for the emblem “Silence” in the several editions of Andrea Alciati's (1492–1550) Emblematum or Emblemes, printed in Lyons between 1549 and 1558 by Macé Bonhomme (ca. 1536–69). Here the scholar sits at his desk, his hand on an open book in front of him, ink and pen close by. Rather than writing, he points to his closed lips, which denote silent reading, but the setting is evocative. Montenay obviously knew the emblem tradition, as she was working on creating her own version in a religious rather than a classical mode.

To summarize, the image of the woman writer developed in France, first in the manuscript tradition with Marie de France and Christine de Pizan, but in later printed books it was largely replaced by images of male writers. Neither Montenay nor Inglis would have seen those royal manuscripts, but Montenay and her engraver Woeiriot must have seen the portraits of male writers, either in books or prints, and from these devised the presentation of Montenay herself, which was then used by Inglis.

The following discussion of Inglis's self-portraits treats Types 1 and 4 first, both done in pen and ink, then Types 2 and 3 painted in watercolor.

CREATING A SELF WITH PEN AND INK

The two types of portraits made by Inglis at the beginning and end of her career were done as line drawings with black or brown ink as variations on Montenay's portrait.Footnote 49 Type 1 dates from 1599–1602, and Type 4 from 1624, the last year of her life.

When Inglis used Montenay's portrait as a prototype for her own in the earlier manuscripts, she made some adjustments rather than creating an exact copy (figs. 5 and 6). Following Montenay, Inglis depicts herself at a desk, with a pen in her right hand and a small book held open by her left hand (Montenay uses a sheet of paper). Both show inkwells on the desk, and both women have a lute and music by their left arm. Both wear contemporary garb, though Montenay's brocaded dress denotes her noble family ties and closeness to the court of Jeanne d'Albret, while Inglis's high-crowned, pleated hat with decorative band over a hood and white coif are middle-class of the period (fig. 7). Instead of the elaborately starched ruff and blackwork-embroidered chemise of her 1595 portrait, painted by an unidentified artist close to the time of her wedding, Inglis depicts herself in “a plain linen smock with a wide, falling band collar underneath a plain buttoned jacket,” over which she wears “a loose gown that is belted at the waist,” the practical outfit of a middle-class woman.Footnote 50 In the earliest of these Type 1 portraits, made in 1599, Inglis is writing at an open-front desk with her gown visible below, revealing a separate patterned skirt beneath her open coat. In the later portraits of 1601 and 1602, her gown is hidden behind the desk, which is covered with a cloth.

Figure 5. Esther Inglis, self-portrait, Type 1, 1601. Ink on paper. The New York Public Library Digital Collections, Spencer Collection, French MS 008, fol. 6r.

Figure 6. Pierre Woeiriot, Georgette de Montenay, 1567. Engraving. Paris, BNF, RESERVE 4-ED-5 (E). By permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 7. Unknown artist, Esther Inglis 1569–1624, Calligrapher and miniaturist, 1595. (Former title: Mrs Esther or Hesther Kello [née Inglis or Langlois], 1569–1624.) Oil on panel. Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, PG 3556.

An engraved portrait of Jeanne d'Albret shows her in a pose similar to that adopted by Montenay and Inglis. As a staunch Protestant and writer (as well as Montenay's patron), Jeanne would have been a model for the younger women, and the portrait is one of very few to depict a woman with the tools of writing, though it was made too late to serve as a model for Woeiriot. Engraved in 1579 by Marc Duval (1530–81), the portrait was planned as part of a series on French royalty, which Duval never completed due to his early death.Footnote 51 Duval could have known Montenay's portrait from her book. His engraving of Jeanne was subsequently copied and distributed by other engravers and could have been known to Inglis. The earliest version depicts Jeanne in an oblong frame with paper and ink stand but no pen. A later version (1596) has her in an oval frame inscribed with her name (fig. 8). This version reverses the image and shows her with writing paper, ink, and pen, sitting at a desk covered with a cloth. In the style of the Montenay and Inglis portraits, this print also includes a verse beneath identifying the sitter and praising her virtue.Footnote 52

Figure 8. Léonard Gaultier, Jeanne d'Albret Queen of Navarre, 1596. Engraving; based on an engraving by Marc Duval. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, www.lacma.org, AC1993.213.14.

The use of rectangular and oval shapes characterizes the Montenay and Inglis portraits as well. Montenay's image is in an unframed rectangle with a simple cartouche below containing a poem by herself, engraved to look like cursive handwriting. The format is drawn from that used in emblems: from top down, motto, picture, and verse are here reproduced as Montenay's name, her portrait, and her poem.Footnote 53

By contrast, Inglis places herself in an elaborate oval frame containing her name, as in Jeanne's portrait. Beneath are laudatory poems by Andrew Melville. She varies the Latin heading for these poems based on the text she is using in her manuscript. For example, in Folger Library, MS X.d.533 and Christ Church College, Oxford, MS 180 the heading reads, “The Psalms of David described by the hand of Esther Inglis (whose likeness you see here)”; in other manuscripts the title phrase changes to “Ecclesiastes and the Song of Songs,” or “The Proverbs of Solomon, described by the hand of Esther Inglis.”Footnote 54 Her headings thus point to herself as the person in the portrait and to the specific text she has copied by hand. Melville's poems beneath praise not only Inglis's mind but also the ability of her hand to depict nature and art. As historian Robert Tittler has noted, written inscriptions were “a feature of the post-Reformation English portrait.” They “allowed men and women of this era to articulate, before a quasi-public audience . . . their personal histories, moral standing, and very identity.” Tittler is talking about painted portraits, but his comments apply equally well to the self-portraits of Inglis.Footnote 55

The oval frame around her self-portrait containing her name, “Esther Anglois Francoise” (Esther Inglis Frenchwoman), adds the date 1601 in the later ones of this series. Departing from the Montenay format, Inglis sets the frame within an elaborate architectural structure decorated with bunches of fruit and leaves, which vary slightly among these images. Inglis would have found many prototypes of portrait heads within an oval frame surrounded by text and a decorative border in prints and books of the period. These include a 1580 woodcut showing the young King James VI from Bèze's Icones, and an engraving of Elizabeth I by Crispijn van de Passe (1565–1637) from his collection of portraits published in 1598 (figs. 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Portrait of James VI of Scotland as a boy, from Théodore de Bèze, Icones, Geneva, 1580. Woodcut. London, British Museum, 1874,1212.515. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 10. Crispijn de Passe the Elder, Portrait of Elizabeth I, from Effigies rerum ac principium . . . depicta et tabellis aeneis incisae a Crispiano Passaeo Zelando 1598. Engraving. London, British Museum, O,7.222. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

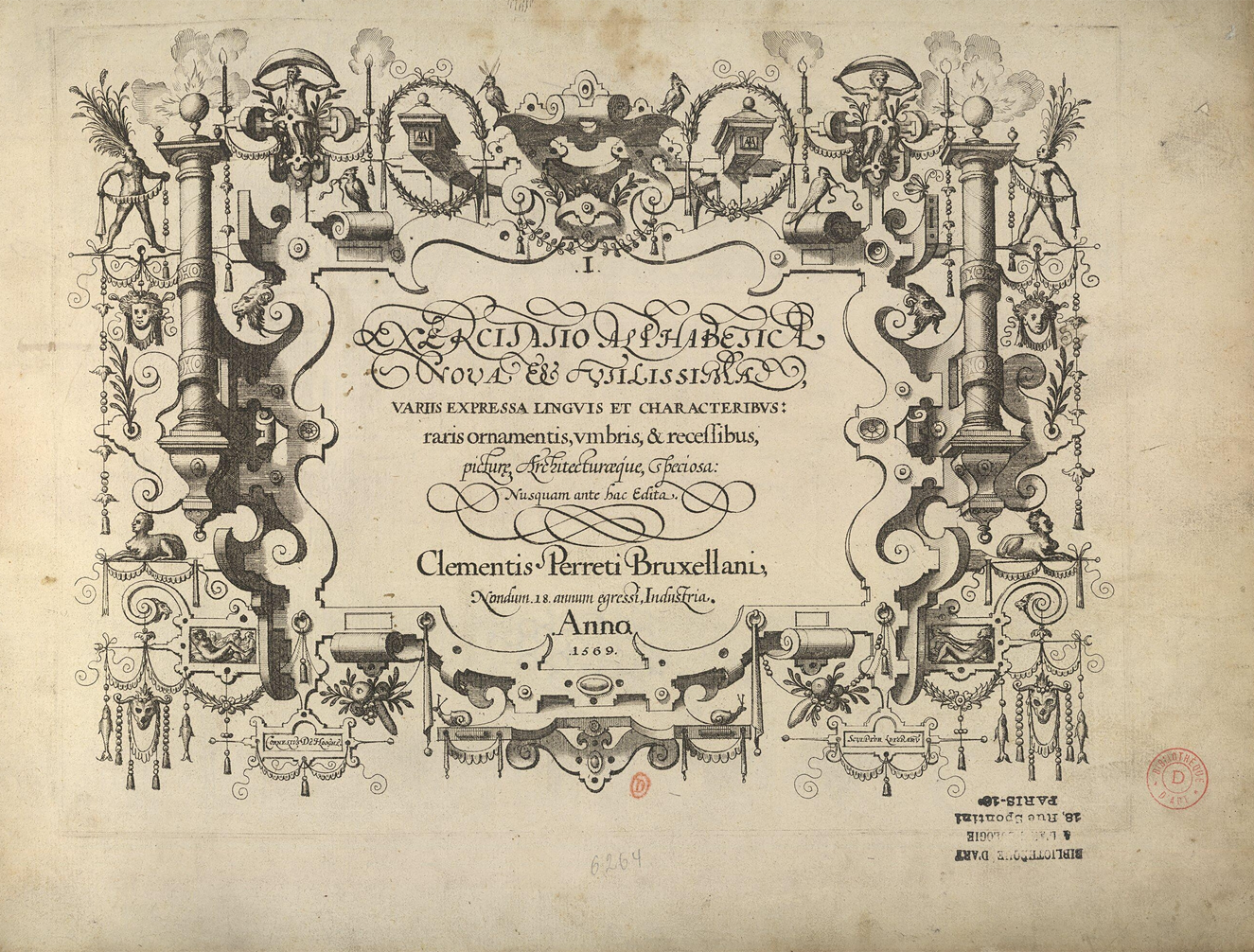

Inglis copied many of her borders from printed books, and indeed, the curled cylinders with piercings and the bunches of fruits and flowers echo those seen in emblem books and elsewhere, including in the borders of handwriting manuals. Inglis certainly knew Clément Perret's (1551–ca. 1591) Exercitatio alphabetica (Training in alphabetical scripts, 1569), a large book of engraved plates displaying writing styles and alphabets within decorative borders. Scott-Elliot and Yeo identify her use of motifs and architectural devices from this book in the group of 1599–1602 manuscripts.Footnote 56

MUSIC, ART, AND PROTESTANT PIETY

Why did Woeiriot and Montenay include a lute and music in her portrait, which Inglis copied? A tradition of self-portraits by women artists was developing during the sixteenth century, and there is an outside chance that, during Woeiriot's travels in Italy and time in Rome, he might have come across at least one of these.Footnote 57 Catherina van Hemessen (1528–ca. 1567) painted the earliest self-portrait of an artist at work at her easel (1548), and painting was joined with music and literature in self-portraits by later women artists.Footnote 58 Sofonisba Anguissola's (ca. 1532–1625) many self-portraits show her with a book (1554), playing a keyboard instrument (1556), and at her easel (ca. 1556). Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614) depicted herself with pen, ink, paper, and books in her study (1579), and playing the spinnet with her easel in the background (1577). Art historian Michael Cole writes that when Fontana combined instrument and easel in one painting, “she made explicit the comparison . . . that Sofonisba had only implied. When she placed the inscription beside the easel, similarly, she associated painting with the ability to read and write.”Footnote 59 Cole goes on to say that Renaissance theory from the time of Leonardo “conjoined painting and music at one moment, painting and writing at another.” These women artists brought the three together, believing “that the young woman who learned to write and to play the keyboard might just as well learn to paint.” In other words, painting rises above a craft to become a real art in the company of other arts.Footnote 60

Some of that prestige is implied by the lute and music in the portraits of Montenay and Inglis. Reading and playing an instrument were skills thought appropriate to women. In his treatise on education (1581), Richard Mulcaster (ca. 1530–1611) advised young women to learn “reading well, writing faire, singing sweete, playing fine,” and the accepted instruments were keyboard or lute.Footnote 61 Women artists, and limners, as Inglis was, might thus present themselves with music to raise their position from a mere artisan to someone skilled in female accomplishments. In choosing to add a lute to their portraits, Montenay and Inglis were showing that putting your poetry into print and engaging in calligraphy were acceptable pursuits for women.

More importantly, however, music and a stringed instrument took on religious significance for both women. The Psalms were central to Protestant theology, and singing them was encouraged as a form of worship, especially in the Calvinist tradition.Footnote 62 In the 1537 Articles setting up the church in Geneva, Calvin stated his wish that psalms should be sung there: “The psalms can stimulate us to raise our hearts to God and arouse us to an ardor in invoking as well as in exalting with praises the glory of His name.”Footnote 63 Later, in the preface to his Commentary on the Book of Psalms, Calvin wrote: “No where is there eyther a more ful and perfect manner of praysing God taughte us, or a sharper spurre put too us for the performance of this dutie of godlines.”Footnote 64 Inglis turned to the Psalms for eleven of her manuscripts, several of which include a picture of King David with his harp, an image that she could have seen reproduced in books of the time.Footnote 65 The lute, like the harp, was a stringed instrument, and psalms could be sung at home to the accompaniment of a lute, as indicated by a book such as Richard Allison's Psalmes of David in Meter, The plaine Song beeing the common tunne to be sung and plaide vpon the Lute (London, 1599).Footnote 66

Piety plays an important role in these portraits. Montenay's poem beneath her portrait says that with her instrument, books, and pen she sings the excellence of God. On the paper in front of her she has written part of the poem, which states that the pen in her hand is not in vain because she writes in praise of Christ. Sara Grieco writes of Montenay, “Both books and music here serve a special purpose for those of the reformed persuasion, for it is by their means that this author, ‘non vaine,’ sings the Lord's praises and exhorts others to follow her example.”Footnote 67 In her book, Inglis has written: “From the Eternal, goodness: From myself, evil, or nothing”—that is, “all good gifts come from God; of myself, I am nothing.”Footnote 68 This distich, appearing in many of her self-portraits, Inglis copied from French Calvinist minister Marin Le Saulx. He ends the lengthy preface of his Théanthropogamie (The marriage of God and man, London, 1577), or the Song of Songs rendered in sonnets, with those verses.Footnote 69 These Protestant women thus write and draw in the service of God. Even more than the lute, dedicating their work to God gives it legitimacy.

REFASHIONING THE SELF FOR A PRINCE

In 1624 when Inglis created her masterpiece for Prince Charles, the reworking of Montenay's Emblemes, she revisited Montenay's portrait, copying it out faithfully in black ink, but then revising it in her self-portrait, which Scott-Elliot and Yeo designate as Type 4. Replacing the lute and music are two instruments of her art, a rule and calipers, resting on a board atop a cloth-covered table in front of her (fig. 11). This is the only self-portrait showing these tools, and they are taken from the first emblem in Montenay's book. Inglis holds a pen in her raised right hand, while an inkpot and book lie nearby, and in front of her a piece of paper on which she has written her perennial motto with the date 1624. Her costume is similar to that in the Type 2 portraits; instead of a collar, she wears a neat white ruff, and her black hat has a lower crown and broader brim—gone are the hood and white coif of Type 1. Such felt hats known as capotains, with brims and higher or lower crowns, were popular in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Inglis places her portrait in an oval frame with a balls-and-bead design, while in the other 1624 manuscripts she uses an oval frame of leaves punctuated with a piece of fruit at each quadrant, a variation on the Type 2 portraits made in 1606–07.

Figure 11. Esther Inglis, self-portrait, Type 4, 1624. Ink on paper. London, British Library, Royal MS 17.D. XVI, fol. 7r. © British Library Board.

The three other versions of this portrait are smaller; one in the Royal Library of Copenhagen (for Prince Charles) shows her pen-in-hand but without desk or motto; another, in the Folger Library, is pasted into a much earlier manuscript she made (without dedication), dated 1600.Footnote 70 Here she has carefully printed her name ESTHER [portrait] INGLIS on each side of the portrait, and perhaps because this is an early manuscript from her colored series, the desk is painted light pink (fig. 12). Scott-Elliot and Yeo surmise that she kept this manuscript over the years to use as a model for her Anglo-Scots translation of Antoine de la Roche Chandieu's (1534–91) Octonaires (Octonaries), which Inglis presents here on facing pages with the French.Footnote 71 The third, a manuscript of the Psalms in the Wormsley Library (also for Prince Charles), is like the one pasted into the Folger manuscript.Footnote 72 In two of these smaller versions, the book on her desk has been moved to the right, replacing the ruler and calipers, yet in all these last portraits she continues to present herself as a self-assured woman, in the fifty-third year of her life, who has by now proven herself by her talent. Though the references to music are gone, her motto remains, a reminder that she still sees her artistry as firmly rooted in her religious faith.

Figure 12. Esther Inglis, self-portrait, Type 4 variation, 1624. Ink on paper. Folger, MS V.a.91, fol. 1v (detail). Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

HER GOLDEN BRUSH: PAINTING THE SELF IN COLOR

We have seen that portraits of women writing appeared quite early in the manuscripts of Marie de France and Christine de Pizan. The portrait miniature itself developed out of the small medallion portraits that decorated French and Flemish manuscripts in the early sixteenth century.Footnote 73 Two artists who enabled this transfer were Jean Clouet (d. 1541) and Lucas Horenbout (ca. 1490/95–1544), who began painting small portraits as stand-alone objects. In England, Horenbout was succeeded by Levina Teerlinc (ca. 1510–76), who worked thirty years at court, and by the next generation of limners, Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver.

The format of miniatures remained similar well into the seventeenth century. Figures were usually depicted turned slightly to the left or the right, sometimes just their head and shoulders; others (as developed by Holbein and Clouet) were depicted waistlength, with hands showing, and sometimes holding an object such as a book. Clouet started using oblong and oval formats, which Hilliard adopted; Holbein stayed with the round format, as did Teerlinc for individual portraits. As Elizabeth Goldring notes, the “one near-constant in virtually all early miniatures, [is that] the sitters are depicted against a plain blue background.”Footnote 74 On this background, the limner often wrote the person's name, age, the date, and sometimes their own initials. Such miniatures obviously informed Inglis's self-portraits when she turned to producing manuscripts in color.

When Inglis began experimenting with color in a small way around 1601, she was still in Edinburgh where she certainly could have seen illuminated manuscripts and portrait miniatures, but her first full-color works occur in 1606, when she was living in or near London. It is even possible that she met Isaac Oliver there, also a French Protestant refugee, attached to the courts of Queen Anna (1574–1619) and Prince Henry, heir to the throne. The introduction could well have been made by an old family friend, David Murray, who held highly responsible positions in the prince's household.Footnote 75 She would have had further opportunities to see not only portrait miniatures but also Flemish-style manuscripts with fruits and flowers painted on gold borders, a design she adapted for many of her own. Indeed, she used vellum for the first (and only) time in three 1606 manuscripts, perhaps trying a technique she observed in London, but none of these manuscripts contain self-portraits, and she quickly reverted to paper, cheaper and easier to procure and work on. The dedicatees of these colored manuscript selections from Proverbs were all attached to the court: Sir Robert Sidney (1563–1626); Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford (1581–1627); and Lady Erskine of Dirletoun (Elizabeth Pierrepoint, d. 1621). Robert Sidney, Viscount Lisle was lord chamberlain of Queen Anna's household, and Lucy Harington was one of the queen's favorites. Lady Erskine's husband Thomas had been educated with James VI in Scotland, followed the king on his accession to the English throne in 1603, and received high positions at court.

These colored manuscripts without self-portraits were followed by the four important manuscripts of 1606 and 1607 that include her first colored self-portraits. The first of these, Latin verses from Genesis, was made for Christian Friis (1556–1616), who visited London in the summer of 1606 in the entourage of Christian IV (1577–1648), king of Denmark, brother of Queen Anna.Footnote 76 This was followed by a Latin summary of the Psalms, made by Inglis for Thomas Egerton, Lord Chancellor (1540–1617) in 1606 according to the title page, but the portrait is dated 1607.Footnote 77 Egerton had been a friend of the Earl of Essex. Inglis says that she made these two manuscripts in London. Also in 1607 she copied Chandieu's Cinquante Octonaires (Fifty octonaries) as a New Year's gift for Prince Henry, who turned thirteen that year.Footnote 78 Henry himself, an ardent Protestant, was developing into a fine collector of books and manuscripts. Finally, in the same year, Inglis presented another copy of the Octonaires as a New Year's gift to Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox (1574–1624), a close relative of the king and important member of the court.Footnote 79 Esther and her husband Bartilmo Kello apparently lived in the parish of St. Mary Colechurch near the Royal Exchange, but by the end of 1607 they were in Mortlake, a town on the Thames near Barnes and Richmond, where she dedicated a manuscript (without a self-portrait) to her landlord, William Jeffrey.Footnote 80

The Type 2 self-portraits created by Inglis are a hybrid between the earlier black-and-white ones based on engravings and woodcuts, and the painted miniature based on the French oval style of Clouet (and later Hilliard and Oliver). The oval format gave Inglis the space to show herself in three-quarter length, behind a desk (fig. 13). Her body now turns slightly to the viewer's right, while she holds a pen in her right hand, with her left hand resting on the pages of an open book in front of her. An ink pot and brush are on the desk, which is covered with a red cloth. The book shows lines indicating writing but there is no readable text, as there was in her earlier portraits. She obviously learned from the miniaturists, laying a flesh-colored base (called “carnation”) for her face, shaping the mouth, cheeks, and chin with a deeper carnation, and using grey-black brushstrokes to model the eyes and head. She prepares the ruff with a grey undercoat, then adds white highlights. The result is rougher than regular miniatures, as she is not working on a smooth vellum-covered card surface.Footnote 81

Figure 13. Esther Inglis, self-portrait, Type 2. Watercolor on paper. Cambridge, MA, Houghton Library, MS Typ 212, fol. 9v (detail). By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Inglis is dressed all in black, but comparison with contemporary miniatures of middle-class women shows that she updated her style in London while maintaining the covered bosom of a modest Protestant. A white ruff replaces the earlier collar, and white lace shows at her cuffs. Gone is the hood, and she wears a black hat with a low crown over her blond hair, which is tamed into a pouf on each side. Her jacket has puffed shoulders, and gold points are visible at the ends of the black ties at her waist. In his study of Scottish sumptuary law, historian Matthew Glozier has pointed to a pronouncement made by the General Assembly of the Kirk (Edinburgh) in 1575 inveighing against the use of embroidery, bright colors, and the wearing of rings or other decorations. The document continues by recommending that the clergy and general populace wear clothing of “grave colour, as black, russet, sad grey. . . . And their wives to be subject to the same.”Footnote 82 Costume historian Maria Hayward adds another element, noting that while black was adopted by “Puritans and Presbyterians . . . they did so for a range of reasons. While donning black could represent a rejection of colour, black clothing had significant social and financial value [and] dyed black textiles were costly and elegant.”Footnote 83 As attested by miniatures, black was a fashionable color, worn in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century by queens as well as noble and middle-class women. Two unknown ladies painted by Oliver and Hilliard, dated 1587 and 1602 respectively, wear black hats with crowns similar to that of Inglis, which “indicates that . . . [they hail] from the urban elite.”Footnote 84 Still visible in three of Inglis's early color manuscripts is the name “Esther Inglis” printed in gold on the rich dark blue background around the left of the portrait, with either “Anno 1607” on the right, or in the case of the Friis manuscript, “London 1606.” (Sadly, the dates on the Royal and NRS manuscripts have now worn off.)

These self-portraits are all set in wreaths of green leaves, punctuated with a gold flower at each quadrant. Inglis uses gold to highlight the leaves as well as the architectural design surrounding them. The book in front of her has gold edges, and her pen is gold, as well as the handle of her scraper. The golden pen held special significance. In at least seven manuscripts from this period, including the ones dedicated to Christian Friis, Sir Thomas Egerton, and Prince Henry, Inglis includes a separate page showing a motif of crossed gold pens within a green wreath (fig. 14). These usually include the motto “Not the Pen But Skill” or “Long Live the Pen.”Footnote 85 The golden pen was the winner's prize in calligraphic contests in England and Europe. Inglis copied the crowned pen motif with motto from a 1591 book with examples of calligraphic hands by Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612), but the motif occurs in other books and prints well into the eighteenth century.Footnote 86 Thus far there is no evidence to show that Inglis herself was ever involved in one of these contests, but in a dedicatory poem by “G. D.” in her 1609 manuscript she is addressed as “the onely Paragon and matcheles Mistresse of the golden pen.” Footnote 87 She was proud of her skill, and by using the motif she added a mark of professionalism to her work.

Figure 14. Esther Inglis, “Vive la Plume.” Watercolor on paper. Cambridge, MA, Houghton Library, MS Typ 212, fol. 101r (detail). By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

The red architectural framework surrounding these portraits is topped by two balls with rays of light shooting from them, below which bunches of fruit and strange masks hang on ribbons. As she did in her earlier black-and-white work, Inglis appears to have taken these motifs as well as the top scrollwork from the engraved title page to Clément Perret's Excercitatio alphabetica (1569), designed by Cornelius de Hooghe (1541–83) (fig. 15). The two birds at the top, painted green to represent parrots, are different from the ones in Perret, and are possibly taken from another source where she may have found the dog and squirrel as well. These are all creatures that appear throughout sixteenth-century engravings such as those by Theodor de Bry (1528–98), Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601), and others. The squirrel could represent diligence and may also be a witty reference to her limning brush, which would likely have been “made of squirrel hairs set in a bird quill and mounted on a wooden stick.”Footnote 88 Thus, as part of her decoration, she depicts the animals that supplied the tools of her art. All of these four major self-portraits in color are rectangular in shape on horizontal pages, leaving no room beneath for poems, as in her black-and-white works. Two of them, dedicated to Christian Friis and Lord Egerton, include poems in praise of Inglis on leaves following her self-portrait.

Figure 15. Clement Perret, Exercitatio alphabetica, title page, Antwerp, 1569. Engraving. Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, collection Jacques Doucet, 4 RES 50. By permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Variations on self-portrait Type 2 occur in several manuscripts. Gone is the elaborate architectural framework, and Inglis depicts herself to the waist against a dark blue background, wearing the low-crowned hat and white or grey ruff, but without her hands or desk showing (fig. 16). She has thus pared down her self-portraits to look more like individual miniatures, which sometimes she made separately and pasted into the manuscript. On two of the earliest, dating from 1609, she has written her name on each side of the oval portrait, a style also used by Hilliard and Oliver.Footnote 89 Two others appear in manuscripts dating from 1612 that Scott-Elliot and Yeo never saw; in one, her portrait is surrounded by a thin gold frame.Footnote 90 Both of these portraits are notable for including beneath them a sonnet, “Esther Inglis Hir Anagramme, Resisting Hel,” again by G. D. This sonnet, based on passages in the books of James and Ephesians, appears also in a Folger manuscript dating from 1607, where it is not accompanied by her self-portrait.Footnote 91

Figure 16. Esther Inglis, self-portrait, Type 2 variation. 1612. Watercolor on paper. Folger MS V.a.665, fol. 7r. Photograph by Georgianna Ziegler from the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC.

The Type 3 self-portrait, again in color, is really a slightly different version of Type 2. She shows herself at waist-length, facing slightly to the viewer's right, and is dressed all in black with a grey ruff against a dark blue background, but she wears a high-crowned hat (fig. 17). The first of these occurs in a copy of Psalms in French, dedicated to Prince Henry in 1612. The second, also a copy of Psalms in French, is dedicated to James I and dates to 1615, by which time Prince Henry had died.Footnote 92 She has drawn the earlier portrait directly onto the page and surrounded it with a slim gold border. The second portrait, without a border, was cut out and pasted into the manuscript. Variations on Type 3 were pasted into two other manuscripts, and, as Scott-Elliot and Yeo suggest, may have been cut down from larger miniatures, focusing now on the head and bust. The earlier one, in a copy of the Quatrains dedicated to Prince Charles, dates from the first day of 1615, when Charles would still have been fourteen years old, but had newly assumed the role of heir to the throne.Footnote 93 With that portrait she returns to her old motto, which she prints on each side of the self-portrait: “From the Eternal, goodness: from myself, evil, or nothing.”Footnote 94 A second variant of Type 3 occurs in another copy of the Quatrains, this one dedicated to “My Very Singular Freinde Ioseph Hall Docter of Divinitie, and Deane of Worchester: . . . Iunii, XXI. 1617.”Footnote 95 The manuscript itself is done in black ink with no color decoration except the self-portrait. That, and the fact that it is pasted in, suggest that the miniature was made earlier.

Figure 17. Esther Inglis, self-portrait, Type 3. 1615. Watercolor on paper. Edinburgh, NLS MS 8874, fol. 4v (detail). By permission of the National Library of Scotland.

HER GOLDEN PEN: THE ART OF CALLIGRAPHY

Calligraphy and limning were closely related. In several of her manuscripts Inglis refers to her “small work written and traced by my pen and brush,” or to “the variety of arms and flowers traced by my pen and brush.”Footnote 96 Inglis's pride in her work is also evidenced by her inclusion of the crossed golden pen motif explored above. As Walter Melion has noted, some instructional books for handwriting “characterize calligraphy as a mode of pictorial representation, making frequent use of the syllogistic claim that as the painter is to the brush, and the brush is to the panel, so the writing master is to the quill, and the quill is to the field of paper.”Footnote 97 Calligraphers’ work was sometimes compared with that of great ancient or contemporary painters such as Apelles and Dürer.Footnote 98 In the systems of the arts that circulated from the time of Leonardo da Vinci, painting was paired with music and/or writing, and artists such as Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana gendered this pairing in their paintings of themselves writing or painting.Footnote 99 In his popular writing manual, A Booke Containing Divers Sortes of Handes, Jehan de Beau-Chesne places good writing with other arts: drawing, painting, and geometry. This is a sort of introductory book, with its “Rules for Children” that could well have been used in Nicolas Langlois's French School. First published in 1571 by Thomas Vautrollier, it was printed nine times through 1611.Footnote 100

Beau-Chesne's book contains a woodcut showing “how you ought to hold your Penne,” a version of which was reproduced in many European writing manuals from the 1540s on (fig. 18). There are two slightly different recommended ways to hold the pen depending on the style of writing required, but the instruction is clear:

Figure 18. Jehan de Beau-Chesne, A booke containing divers sortes of hands, London, 1602. “How you ought to hold your penne,” woodcut, A3r. STC 6450.2. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The instructions continue: “Ink alwayes good store on right hand to stand,” and “Waxe, quilles and penknife see alwayes ye beare.”Footnote 101

In her 1599 black-and-white self-portraits, Inglis shows herself sitting upright at a desk, with the ink pot strategically placed in front of her right hand, resting on the table (see fig. 5). On first view, she seems to be holding the pen incorrectly; while the pen is grasped between the thumb and next two fingers, the small finger extends under them outward on the desk, as shown in one of Beau-Chesne's “Naught” images. I propose, however, that we are meant to read her hand not as writing, but as resting before dipping into the ink pot, over which the pen hovers. In the Type 2 colored version of this self-portrait, Inglis holds her pen in a similar manner while resting her hand on the table, not yet writing. In these later portraits, which exclude musical elements, she includes what appears to be a penknife or scraper next to the ink pot, another important tool for calligraphers. An instructive comparison can be made with an early self-portrait by Sofonisba Anguissola, in which she holds two brushes in her left hand, while more are laid out on a palette lying on the table before her, unlike later portraits where she depicts herself painting.Footnote 102 In a pose similar to that of Inglis, Anguissola gazes directly out at the viewer, both women appearing to say, “I present myself as a skilled artist with the tools of my profession.”Footnote 103

The late black-and-white portraits, Type 4, show more direct influence from Georgette de Montenay's portrait. Here her right hand holding the pen is raised in front of her chest, as Montenay holds hers. In the chief of these, her actual copy of Montenay's Emblemes, Inglis replaces the lute and music with two more of the calligrapher's tools, calipers and a rule (see fig. 11).Footnote 104 These appear early on in a woodcut showing tools of the trade in sixteenth-century writing books by Giovanni Tagliente and Giovanni Palatino. Their inclusion by Inglis not only focuses on her skill as a writing mistress but also links her with the first emblem in Montenay's book showing Jeanne d'Albret as the wise woman building the house of the Lord. There, a rule and calipers lean against a pillar on the right. When Inglis redirected this emblem to Elizabeth of Bohemia, she included both tools, and then added them to her own self-portrait, signifying not only her drawing skills but also her association with these wise women doing God's work.Footnote 105 Her left hand grasps what may be a wad of bread, which was used to erase any pencil lines she might have used to keep her writing straight: “The same to be done [draw lines] is best with blacke leade, / Which written betwene, is clensed with bread.”Footnote 106 This detail is evident in the Emblemes manuscript, but not in the three other late Type 4 portraits, where the calipers and rule are replaced by a little book with ties at her left arm.

I have shown elsewhere the importance of the hand in Inglis's presentation.Footnote 107 In her dedications, she refers many times to the work of her own hand in creating her little books: to Prince Maurice of Nassau “written by my hand”; to Queen Elizabeth, this book “which I wrote in diverse sorts of letters”; and finally, in the 1624 Emblemes, she tells Prince Charles that this manuscript represents two years of work by her “totering right ![]() , now being in the age of fiftie three yeeres.”Footnote 108 The scholar-humanists who wrote dedicatory poems to Inglis, which she frequently included in her manuscripts, also dwell on her hand. Andrew Melville wrote, “This single hand, a rival of nature, expresses a thousand figures, animating small symbols with brushstrokes. And it creates living symbols, breathing tokens of heaven.” John Johnston added, “By what better hand inspired by a heavenly intelligence could these things be depicted? . . . Mind and hand compete, as do matter and art. You owe these things to the Gods.”Footnote 109 From early on, calligraphy was theorized as a divine art. In the dedication to his handwriting manual (1555), Wolfgang Fugger (1519/20–68) wrote that good art is “that which, thought out by a keen mind and put into practice by a skilful hand, will tend to the glory of God and the service of men.”Footnote 110 Likewise, calligrapher Jan van de Velde (1568–1623) defended the art of good writing to a mathematician friend, noting that while writing is important for perpetuating memory, it is most important as the means by which the Gospels were transmitted.Footnote 111 All her life, as she copied out biblical verses and religious poetry, Inglis strategically foregrounded her own belief that what she was doing was a sacred task, using her pen with the skill given her by God.

, now being in the age of fiftie three yeeres.”Footnote 108 The scholar-humanists who wrote dedicatory poems to Inglis, which she frequently included in her manuscripts, also dwell on her hand. Andrew Melville wrote, “This single hand, a rival of nature, expresses a thousand figures, animating small symbols with brushstrokes. And it creates living symbols, breathing tokens of heaven.” John Johnston added, “By what better hand inspired by a heavenly intelligence could these things be depicted? . . . Mind and hand compete, as do matter and art. You owe these things to the Gods.”Footnote 109 From early on, calligraphy was theorized as a divine art. In the dedication to his handwriting manual (1555), Wolfgang Fugger (1519/20–68) wrote that good art is “that which, thought out by a keen mind and put into practice by a skilful hand, will tend to the glory of God and the service of men.”Footnote 110 Likewise, calligrapher Jan van de Velde (1568–1623) defended the art of good writing to a mathematician friend, noting that while writing is important for perpetuating memory, it is most important as the means by which the Gospels were transmitted.Footnote 111 All her life, as she copied out biblical verses and religious poetry, Inglis strategically foregrounded her own belief that what she was doing was a sacred task, using her pen with the skill given her by God.

CONCLUSION: ESTHER INGLIS ON THE MARGINS OF MANUSCRIPT AND PRINT

The purpose of this essay has been to rethink the self-creation of an early modern Franco-Scottish woman, and also to assess her self-portraits in some detail by surveying the traditions of French female author portraits in manuscript and print, as well as images in printed books and painted miniatures that more directly influenced her work. Inglis's focus on the handmade quality of the physical objects she created is one of their major appeals for her audience, in addition to the pious texts enclosed. In the dedications, while using the humility topos adopted by both female and male authors, Inglis presents these as works by her own skill and hands: “this little book written by my hand in several sorts of characters,”Footnote 112 and she hopes that they will be kept in a private cabinet by the recipient—precious works to be taken out and enjoyed, just as portrait miniatures often were.Footnote 113 Her self-portraits personalize her little books, highlighting her participation as one of the many women who used their skills to advance the Protestant cause.

This acknowledgment of a sacred calling did not preclude her pride in her own work, her desire to present her self in person, as it were. In writing about the development of the author portrait in France, Cynthia J. Brown shows how printed author portraits derived from the two strands of manuscript author portraits: “authors presenting or authors authoring.” “Both of these images depicting writers—presentation scenes of poet and patron and generic woodcuts of the writer alone—find their source in conventional miniatures that had decorated manuscripts for centuries.”Footnote 114 I suggest that Inglis's self-portraits lie in the margin between presentation and author portrait, functioning as both. Rather than showing an actual scene of herself presenting her manuscript to its recipient, Inglis depicts herself, often with her writing tools, inscribing her authority. Her portrait is part of the preliminary paratext that also includes synecdochical references to her dedicatee/patron, such as coats of arms and dedications, as well as dedicatory verses to her recipients and to herself. It is in this liminal area that Inglis creates a self by evoking her place among the Franco-Scottish, refugee, Calvinist, humanist, and artistic communities and spaces that formed her.