Introduction

In highly dynamic and changing environments, the ability to generate radical ideas is crucial for organizations to maintain a sustainable competitive advantage (Malik, Choi, & Butt, Reference Malik, Choi and Butt2019; Venkataramani, Richter, & Clarke, Reference Venkataramani, Richter and Clarke2014; Zhang, Zhang, Gu, & Tse, Reference Zhang, Zhang, Gu and Tse2022). In response, organizations seek to foster employee radical creativity. One strategy that organizations employ is the establishment of stretch goals (Cunha, Giustiniano, Rego, & Clegg, Reference Cunha, Giustiniano, Rego and Clegg2017; Lemoine, Blum, & Roman, Reference Lemoine, Blum and Roman2016; Yang, Reference Yang2024). Stretch goals refer to organizational objectives that seem impossible to achieve given current capabilities but may be realized through breakthrough new approaches (Gary, Yang, Yetton, & Sterman, Reference Gary, Yang, Yetton and Sterman2017; Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless, & Carton, Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011). Indeed, some companies, such as Southwest Airlines and Walmart, have successfully promoted breakthrough ideas with stretch goals (Ahmadi, Jansen, & Eggers, Reference Ahmadi, Jansen and Eggers2022). However, there have also been cases where the use of stretch goals did not yield the desired outcomes, as seen with Volkswagen (Gaim, Clegg, & Cunha, Reference Gaim, Clegg and Cunha2021). Therefore, the relationship between stretch goals and employee radical creativity may be complex.

Although scholars have begun to examine the impact of stretch goals on organizational members, empirical research in this area remains relatively limited. These investigations have predominantly centered on outcome variables, such as unethical behavior, relationship conflict, work-family conflict, task persistence, task accuracy, emotional exhaustion, and abusive supervision (e.g., Chen, Zhang, & Jia, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2019, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2020, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2021a, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2021b; Mawritz, Folger, & Latham, Reference Mawritz, Folger and Latham2014; Roose & Williams, Reference Roose and Williams2018; Zhang & Jia, Reference Zhang and Jia2013). Ahmadi et al. (Reference Ahmadi, Jansen and Eggers2022) did explore the relationship between stretch goals and employee creativity, but their primary focus was on the fruitful and futile dimension of ideas (represented by whether the ideas are accepted by the organization) while neglecting the differences in the extent to which ideas can improve the status quo. As Gilson and Madjar (Reference Gilson and Madjar2011) have asserted, specific factors may influence distinct forms of creativity in various ways. Radical ideas deviate significantly from existing practices and are fraught with implementation challenges (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Madjar, Greenberg, & Chen, Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011), aligning with the extremely novel and difficult characteristics of stretch goals (Sitkin et al., Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011). Therefore, a more detailed exploration of the impact of stretch goals on employee radical creativity is necessary.

We utilize signaling theory and draw on existing creativity-related research to address this foregoing gap. According to signal theory, signals can convey vital information about intent (Connelly, Certo, Ireland, & Reutzel, Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011; Elitzur & Gavious, Reference Elitzur and Gavious2003). From an organizational perspective, because stretch goals involve extremely high expectations, employees can only achieve stretch goals with dramatically new approaches (Gary et al., Reference Gary, Yang, Yetton and Sterman2017; Sitkin et al., Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011). The difference between radical and incremental methods lies in their higher level of risk (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011). Therefore, the organization's intention in setting stretch goals should be to encourage employees to take risks and engage in radical creative activities.

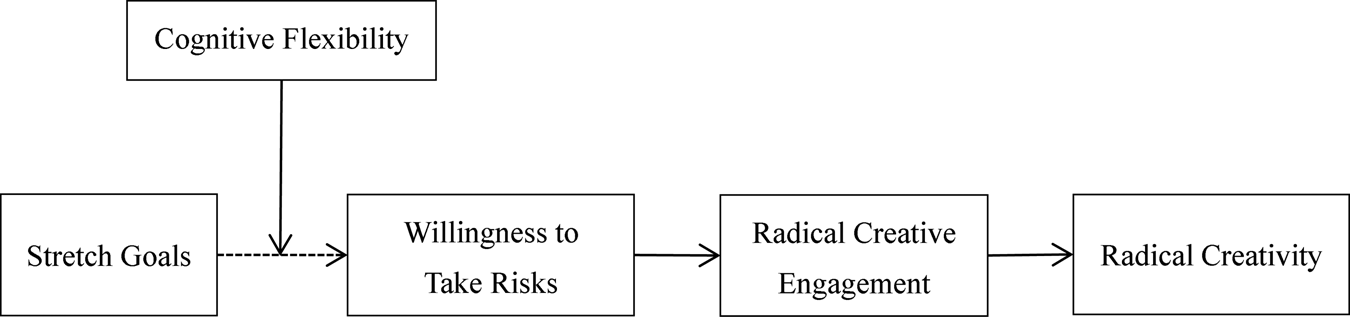

However, not all employees can correctly interpret the organizational intention associated with the signals and act accordingly (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011). When confronted with unattainable goals, employees' brains often enter a survival mode, during which rational thinking becomes difficult, and employees tend to repeat familiar behaviors. In more extreme cases, employees may experience feelings of anger, fear, impulsiveness, or even desperation, which can lead to uncontrolled actions. Only when employees transition from this survival mode to a learning mode can they potentially think rationally and comprehend the organization's intent in setting stretch goals (Ford & Wortmann, Reference Ford and Wortmann2013). Employees with high cognitive flexibility may be well-positioned to make this shift, as they are more inclined to perceive situations as controllable (Ratner, Burrow, Mendle, & Thoemmes, Reference Ratner, Burrow, Mendle and Thoemmes2023) and possess the capacity to consider issues from various angles (Dheer & Lenartowicz, Reference Dheer and Lenartowicz2019; Nijstad, De Dreu, Rietzschel, & Baas, Reference Nijstad, De Dreu, Rietzschel and Baas2010). Therefore, we propose that the interplay between stretch goals and cognitive flexibility influences an employee's willingness to take risks, which subsequently affects their level of radical creative engagement and, ultimately, their radical creativity.

The proposed theoretical model is depicted in Figure 1. We conducted two field studies to validate this model. This research has three main contributions. First, examining the mechanisms and boundary conditions of stretch goals on a specific type of creativity – namely, radical creativity – this article provides further insights into the relationship between stretch goals and creativity. Second, in response to Chen et al.'s (Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2020) call to explore boundary conditions that can make stretch goals either advantageous or detrimental, we explore the role of cognitive flexibility in the relationship between stretch goals and employee radical creativity. Last, the introduction of the concept of radical creative engagement should encourage further research on the creative process.

Figure 1. Theoretical model

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Signaling Theory and Stretch Goals

Signaling theory centers on the process through which signalers disseminate signals to receivers and procure feedback from them (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011). In this process, signalers possess information specific to the quality or intention of their signals (Elitzur & Gavious, Reference Elitzur and Gavious2003; Venkataramani, Bartol, Zheng, Lu, & Liu, Reference Venkataramani, Bartol, Zheng, Lu and Liu2022), and they benefit from the effective transmission of this information when receivers respond accordingly (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011). Concurrently, though receivers may not yet possess this information, they are aware of its potential to support sound decision-making, thus providing an incentive for them to acquire it (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011; Ho & Astakhova, Reference Ho and Astakhova2020).

In the context of our study, stretch goals are defined as organizational goals with an objective probability of attainment that may be unknown but are seemingly impossible given current practices, skills, and knowledge (Sitkin et al., Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011). They differ from typical challenging goals in two fundamental ways: extreme difficulty and extreme novelty (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Giustiniano, Rego and Clegg2017; Zhang & Jia, Reference Zhang and Jia2013). Given the extreme novelty of stretch goals, there is no known path to achieving them using the organization's current capabilities. Consequently, to attain these goals, employees need to generate new ideas (Sitkin et al., Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011). Additionally, due to the extreme difficulty of stretch goals, incremental ideas will likely prove insufficient in helping organizations meet their ambitious expectations. Thus, the ideas that employees derive must be radical in nature (Gary et al., Reference Gary, Yang, Yetton and Sterman2017; Sitkin et al., Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011). Radical ideas involve higher risk and uncertainty compared to incremental ideas (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011). Consequently, stretch goals may represent an organization's intention for employees to take risks and invest more effort in radical creative activities.

However, employees may not necessarily interpret the organizational intention associated with the signals and act accordingly, as the effectiveness of the signal depends on a range of factors (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011; Srivastava, Reference Srivastava2001). Among these, the receiver's attributes are crucial (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Certo, Ireland and Reutzel2011). We propose that cognitive flexibility of employees may be a crucial attribute related to how employees interpret signals.

Interactive Effect of Stretch Goals and Cognitive Flexibility on Employees' Willingness to Take Risks

According to Ford and Wortmann (Reference Ford and Wortmann2013), when individuals are exposed to high levels of stress, their brains enter a survival mode. In this state, individuals struggle to think rationally and tend to rely on repetitive, well-practiced actions. In more severe cases, individuals may become angry, impulsive, or even desperate, leading to uncontrolled behavior – such as engaging in unethical behavior. Rational thinking becomes possible only when the brain shifts from a survival mode to a learning mode.

Cognitive flexibility comprises awareness of the available options and alternatives in any situation, openness to adaptation, and self-efficacy in flexibility (Martin & Rubin, Reference Martin and Rubin1995). When employees possess high cognitive flexibility, they are more inclined to perceive situations as controllable (Ratner et al., Reference Ratner, Burrow, Mendle and Thoemmes2023) and possess the capacity to consider issues from various perspectives (Dheer & Lenartowicz, Reference Dheer and Lenartowicz2019; Kapadia & Melwani, Reference Kapadia and Melwani2021; Nijstad et al., Reference Nijstad, De Dreu, Rietzschel and Baas2010; Zhu, Bauman, Young, & Schaubroeck, Reference Zhu, Bauman, Young and Schaubroeck2023). Therefore, when facing the high-pressure situation of stretch goals, employees with high cognitive flexibility are more likely to transcend their familiar, routine thinking and switch from survival mode to learning mode.

Furthermore, when employees think rationally in a learning mode, they are more likely to interpret the intention behind stretch goals accurately and willingly align their attitudes with the organization's intent. This is because they can tap into a broad range of cognitive categories (De Dreu, Baas, & Nijstad, Reference De Dreu, Baas and Nijstad2008; Nijstad et al., Reference Nijstad, De Dreu, Rietzschel and Baas2010; Xu, Mehta, & Hoegg, Reference Xu, Mehta and Hoegg2022) and make novel connections among different concepts (Kapadia & Melwani, Reference Kapadia and Melwani2021; Kundro, Reference Kundro2023). They also demonstrate a strong willingness to adapt to novel situations (Dheer & Lenartowicz, Reference Dheer and Lenartowicz2019; Martin & Rubin, Reference Martin and Rubin1995) and maintain an optimistic outlook concerning their ability to manage uncertainty (Dheer & Lenartowicz, Reference Dheer and Lenartowicz2019). Accordingly, we propose that, for employees with high cognitive flexibility, stretch goals positively influence their willingness to take risks (i.e., employees' proneness to engage in the cultivation of new ideas despite uncertain outcomes; Andrews & Smith, Reference Andrews and Smith1996).

In contrast, we propose that, when organizations implement stretch goals, employees with low cognitive flexibility are less inclined to take risks. This is because employees with low cognitive flexibility tend to have a narrow and focused scope of attention, making them less likely to entertain divergent perspectives (Kapadia & Melwani, Reference Kapadia and Melwani2021; Rothman & Melwani, Reference Rothman and Melwani2017; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Mehta and Hoegg2022). These factors reinforce their preoccupation with survival concerns. In essence, their brains remain in survival mode, leading to irrational behavior where they rely on conventional strategies to achieve their goals or engage in uncontrolled behaviors (Ford & Wortmann, Reference Ford and Wortmann2013).

Even when employees with low cognitive flexibility can shift to learning mode for rational thinking, their inclination to consider a limited number of alternatives (Rothman & Melwani, Reference Rothman and Melwani2017) and their restricted ability to connect different concepts (Kapadia & Melwani, Reference Kapadia and Melwani2021; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Mehta and Hoegg2022) pose a challenge in accurately interpreting the organization's intentions. Their lack of confidence in their capacity to act effectively (Chung, Su, & Su, Reference Chung, Su and Su2012; Martin & Rubin, Reference Martin and Rubin1995) reduces the likelihood of aligning their attitudes with the organization's intentions. Given limited attentional resources, when employees rely on conventional strategies to achieve their goals or engage in uncontrollable actions (such as resisting goals or engaging in deception), their willingness to take risks in proposing new ideas decreases. The foregoing disquisition leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1a and H1b): The interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility influences employees' willingness to take risks as follows: (a) for employees with high cognitive flexibility, stretch goals positively affect their willingness to take risks; (b) for employees with low cognitive flexibility, stretch goals negatively affect their willingness to take risks.

Mediating Role of Willingness to Take Risks

Attitudes usually influence behavioral outcomes through behavioral processes. Therefore, we further propose that the interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility influences employees' willingness to take risks, thereby affecting their level of engagement in radical creative activities. Drawing on existing research on radical creativity and creative process engagement (e.g., Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011; Zhang & Bartol, Reference Zhang and Bartol2010), we define radical creative engagement as ‘the extent to which employees' invest their time and effort in the process of generating radically novel ideas'. Because radical ideas are characterized as a departure from old routines and conventions, the associated radical creative activities involve significantly greater unanticipated risks and uncertain rewards (Alexander & Van Knippenberg, Reference Alexander and Van Knippenberg2014; Liu, Ouyang, & Pan, Reference Liu, Ouyang and Pan2023; Sung, Rhee, Lee, & Choi, Reference Sung, Rhee, Lee and Choi2020). Thus, employees need greater willingness to navigate such challenges (Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang, Gu and Tse2022). Willingness to take risks provides employees with the mindset necessary to engage in high-risk activities (Andrews & Smith, Reference Andrews and Smith1996; Dewett, Reference Dewett2006). Consequently, employees with a high willingness to take risks are more likely to accept the uncertainty and risk associated with radical creative activities and, as a result, become more engaged in them. However, employees with low willingness to take risks are reluctant to bear the high risks and uncertainty associated with radical creative activities, so they invest less effort in these activities.

Combining the hypothesis about the effect of the interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on employees' willingness to take risks (H1), we present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2a and H2b): Employees' willingness to take risks mediates the effect of the interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on their radical creative engagement as follows: (a) for employees with high cognitive flexibility, stretch goals promote radical creative engagement by enhancing their willingness to take risks; (b) for employees with low cognitive flexibility, stretch goals inhibit their radical creative engagement by reducing their willingness to take risks.

A Comprehensive Model

We also anticipate that the interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility influences employees' willingness to take risks, which, in turn, influences their radical creative engagement – and ultimately their radical creativity. Creativity springs out of creative activities (e.g., Amabile, Reference Amabile1983; Mumford, Reference Mumford2000; Zhang & Bartol, Reference Zhang and Bartol2010). As previously mentioned, radical creative engagement refers to individuals' self-assessment of their level of engagement vis-à-vis their time and effort in radical creative activities. Radical creativity, though, pertains to ideas that significantly deviate from existing routines (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Gong, Wu, Song, & Zhang, Reference Gong, Wu, Song and Zhang2017; Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011). In essence, radical creative engagement emphasizes the process of generating radical ideas, but radical creativity represents the tangible output of this process (c.f., Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Shalley & Gilson, Reference Shalley and Gilson2004; Zhang & Bartol, Reference Zhang and Bartol2010). As employees dedicate more time and energy to radical creative activities, they are more likely to generate increasingly radical ideas. So, we further propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3a and H3b): Employees' willingness to take risks and undertake radical creative engagement sequentially mediate the effect of the interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on their radical creativity as follows: (a) for employees with high cognitive flexibility, stretch goals enhance their radical creativity by promoting their willingness to take risks and undertake radical creative engagement; (b) for employees with low cognitive flexibility, stretch goals impede their radical creativity by inhibiting their willingness to take risks and undertake radical creative engagement.

Study 1

Sample and Procedure

Study 1 was executed in research and development (R&D) departments in China (it was conducted as part of a larger data collection effort and was not preregistered). The departments were contacted through MBA students from a central university, and respondents (i.e., R&D employees) completed all measures through mail questionnaires. R&D departments constituted an appropriate sample for our study because they provided employees with ample opportunity to undertake radical creative activities.

We chose to have employees report on the study variables for two reasons. First, individuals perceive goal difficulty differently, and self-assessment of stretch goals is especially in line with the context of our study and is consistent with current methods of measuring stretch goals (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2020; Mawritz et al., Reference Mawritz, Folger and Latham2014; Zhang & Jia, Reference Zhang and Jia2013). Second, since cognitive flexibility, willingness to take risks, and radical creative engagement all emphasize individual internal states, it is logical to collect the data from participants themselves (Andrews & Smith, Reference Andrews and Smith1996; Martin & Rubin, Reference Martin and Rubin1995; Zhang & Bartol, Reference Zhang and Bartol2010).

Our final sample consisted of 346 participants, with a response rate of 67% (after excluding incomplete questionnaires). Among these respondents, 38.4% were female, and 91% held at least one college degree. The average age was 32.03 years (SDage = 7.62), and mean organizational tenure was 5.01 years (SDtenure = 4.32). Respondents belonged to a variety of industries: transportation (28.3%), biomedicine (12.4%), manufacturing (13.3%), and finance (46.0%). We assessed potential nonrespondent bias and found no significant differences in gender (χ²(1) = 1.82, p > 0.05) or age (t(470) = −0.98, p > 0.05) between respondents and nonrespondents.

Measures

Unless otherwise specified, all items were taken from established scales originally developed in English. To ensure consistency in meaning, we followed Brislin's (Reference Brislin1986) translation and back-translation procedure. All variables were assessed using 7-point Likert-type scales, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Stretch goals

We measured stretch goals using a six-item scale from Zhang and Jia (Reference Zhang and Jia2013). A sample item is, ‘I find that the goal in my work unit is too high'. Cronbach's α was 0.932.

Cognitive flexibility

We assessed cognitive flexibility using Martin and Rubin's (Reference Martin and Rubin1995) 12-item scale. A sample item is, ‘I have the self-confidence necessary to try different ways of behaving'. Cronbach's α was 0.914.

Willingness to take risks

We evaluated willingness to take risks using a three-item scale adapted from Andrews and Smith's (Reference Andrews and Smith1996) risk-taking scale. A sample item is, ‘I like to play it safe when I am developing new ideas’ (reverse scored). Cronbach's α was 0.793.

Radical creative engagement

We developed and validated a five-item scale to assess radical creative engagement using Hinkin's (Reference Hinkin1998) scale development procedure. First, we examined Zhang and Bartol's (Reference Zhang and Bartol2010) creative process engagement scale and Sheng and Chien's (Reference Sheng and Chien2016) radical innovation scale to create seven initial items for radical creative engagement. Four creativity and innovation experts (i.e., professionally educated university instructors) assayed these seven items for redundancy and clarity, resulting in deletion of two of them. The remaining five items were as follows: ‘I spend considerable time inventing completely new products and services', ‘I strive to generate entirely new alternatives before I choose the final solution', ‘I try to devise potential solutions that are completely different from the established ways of doing things', ‘I look for connections in seemingly completely different fields', and ‘I experiment with completely new approaches at work'.

We then examined content validation of this measure. Fourteen experts in organizational behavior – five professors and nine doctoral students – were asked to assess the extent to which the five items matched the definitions that we provided, using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (the item is an extremely bad match) to 7 (the item is an extremely good match). The results indicated strong definitional correspondence (i.e., 6.11; Colquitt, Sabey, Rodell, & Hill, Reference Colquitt, Sabey, Rodell and Hill2019), and the interrater agreement among the experts was high (rwg = 0.89; James, Demaree, & Wolf, Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1984); these values provided evidence of content validity.

In addition, we utilized two independent samples from Credamo (i.e., a data-collection platform) to examine the reliability and validity of our radical creative engagement measure. Sample 1 (n = 296; 62.5% female; M age = 31.64 years; M tenure = 5.89 years) was used in an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring. One factor was found with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0 accounted for 70.43% of the variance. The factor loadings were satisfactory (i.e., ranging from 0.81 to 0.86), and internal consistency was high (Cronbach's α = 0.919), hence supporting the reliability and factor structure of our measure.

We examined convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity of the newly developed scale using Sample 2 (n = 294; 66.0% female; M age = 34.36 years; M tenure = 6.75 years). We assessed employees' radical creativity (Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011; Cronbach's α = 0.883), which was positively correlated with our newly developed scale (r = 0.24, p < 0.01). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed that a two-factor model fit the data significantly better than a one-factor model (Δχ2(1) = 444.66, p < 0.001). We also measured employees' openness to experience, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003). These results showed a significant positive correlation between our scale and openness to experience (r = 0.25, p < 0.01), a significant negative correlation with neuroticism (r = −0.30, p < 0.01), and no correlation with agreeableness (r = 0.07, p > 0.05).

Additionally, we measured perceived organizational valuing of creativity (Farmer, Tierney, & Kung-McIntyre, Reference Farmer, Tierney and Kung-McIntyre2003; Cronbach's α = 0.932); it had a significant positive correlation with our radical creative engagement scale (r = 0.24, p < 0.01). CFA confirmed that a two-factor model fit the data significantly better than a one-factor model (Δχ2(1) = 532.89, p < 0.001). These findings, therefore, supported the discriminant, convergent, and criterion validity of our measure. Accordingly, in Study 1, we measured radical creative engagement with the newly developed five-item scale. The scale exhibited high reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.909).

Control variables

We controlled for employees' gender (0 = male, 1 = female), organizational tenure (in years), and education (1 = college degree and lower to 4 = doctorate degree) in the analysis. We did so, owing to their potential association with our mediation and outcome variables (Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Rhee, Lee and Choi2020). To account for differences across industries, we also created three dummy variables to control for the industry in which data were collected. Although age was also a potential confounding variable, we did not include it in our analysis due to the possibility of collinearity with organizational tenure. However, we conducted further analyses controlling for age instead of tenure and found that the significance patterns remained consistent. We also retested the model after deleting all control variables and determined that the significance of the results did not change.

Analytic Strategy

Data analysis was conducted using Mplus8 and RStudio. We performed path analysis to validate the hypotheses. Given the nested structure of the data (i.e., employees were nested in 101 units), we employed a mixed-effects regression model to account for any nonindependent influences within groups (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2009). To evaluate the conditional effects, we plotted the interaction effect and conducted a simple slope test (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991). To test the conditional indirect effects, we examined the 95% Ci's for the indirect effects at the ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ values of cognitive flexibility using the Monte Carlo simulation approach (with 20,000 repetitions).

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

The CFA results showed that the four-factor model (i.e., stretch goals, willingness to take risks, cognitive flexibility, and radical creative engagement) indicated a good fit with the data (χ² = 216.094; df = 113; CFI = 0.974; TLI = 0.968; RMSEA = 0.051; SRMR = 0.036) and exhibited a better fit than other alternative models. These findings demonstrated that the selected measures offered satisfactory discriminant validity.

Common method variance check

The self-reported data in this study may introduce potential common method biases. Thus, we incorporated a latent common method factor into the hypothesized four-factor model to examine the potential issue of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), We found that its addition improved the fit (Δχ²(17) = 84.847, p < 0.001). However, the change in all fit indices was less than 0.02 (Chen, Zhang, & Jia, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2021b; Li, Ling, & Liu, Reference Li, Ling and Liu2012), and the variance extracted by the common methods factor was only 0.044, far lower than the critical value of 0.5 (Dulac, Coyle-Shapiro, Henderson, & Wayne, Reference Dulac, Coyle-Shapiro, Henderson and Wayne2008; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, Reference Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black1998). Therefore, common method bias was unlikely to affect the findings of this study significantly.

Hypothesis testing

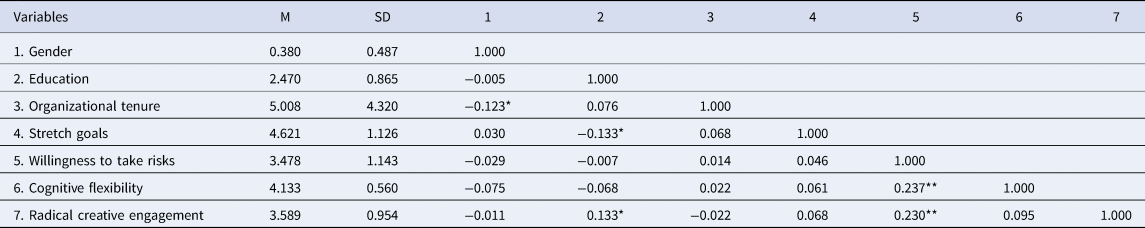

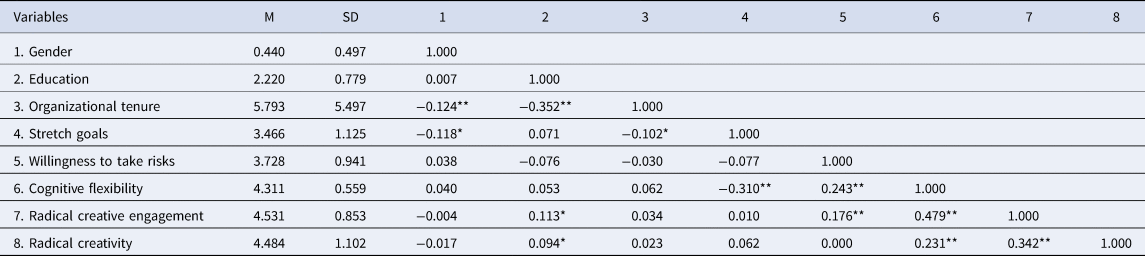

Shown in Table 1 are the descriptive statistics and correlations among the main variables. Path analysis results are depicted in Table 2.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables (Study 1)

Notes: N = 346; all variables are unstandardized. Gender: 0 = male; 1 = female. Education: 1 = college degree or lower; 2 = bachelor's degree; 3 = master's degree; 4 = doctorate degree. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

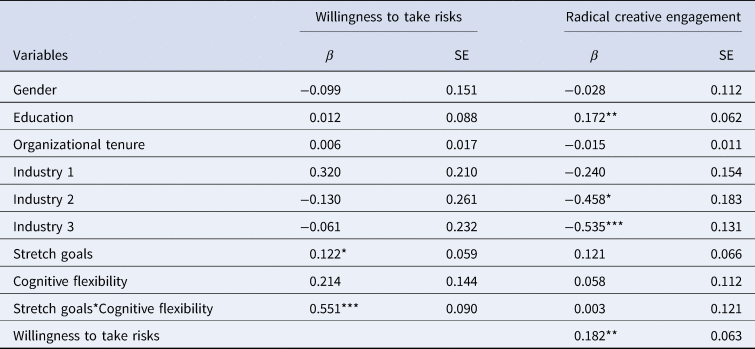

Table 2. Path analysis results (Study 1)

Notes: N = 346; β coefficients are unstandardized. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

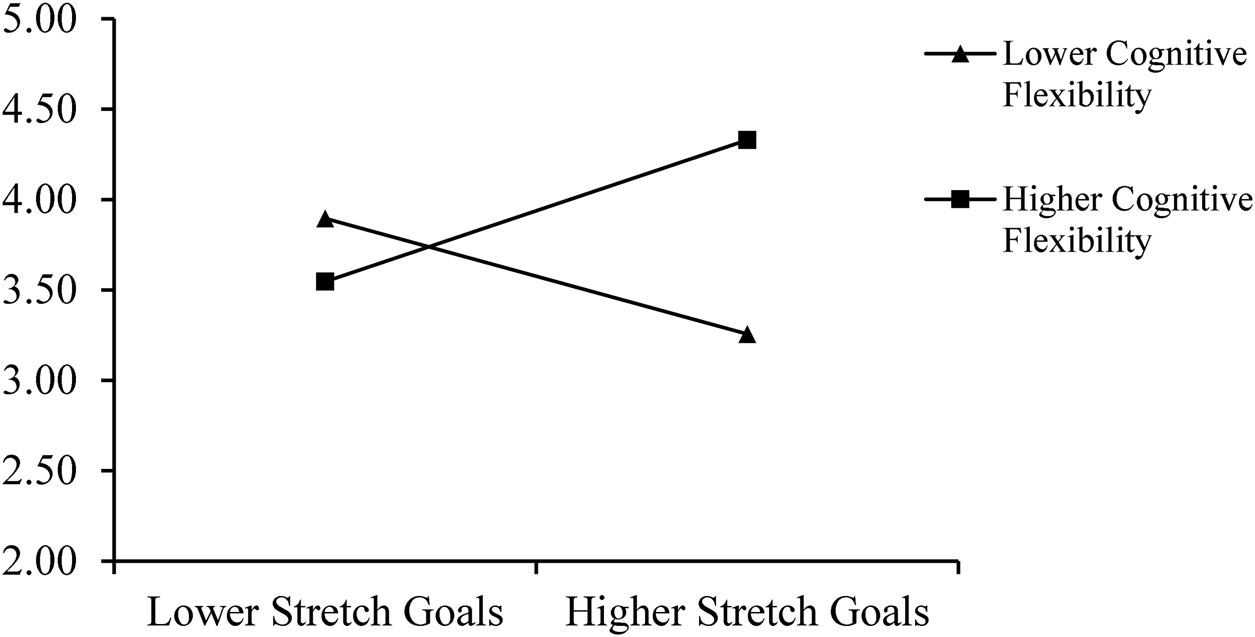

As illustrated in Table 2, the interactive effect of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility significantly predicted employees' willingness to take risks (β = 0.551, p < 0.001). We visualized this interaction effect in Figure 2 and conducted a simple slope test. Consistent with our hypotheses, when employees' cognitive flexibility was high, the relationship between stretch goals and employees' willingness to take risks was positive and significant (β = 0.430, p < 0.001). However, when their cognitive flexibility was low, the relationship was negative and significant (β = −0.187, p < 0.01). These findings, therefore, supported both H1a and H1b.

Figure 2. Interactive effect of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on employees' willingness to take risks (Study 1)

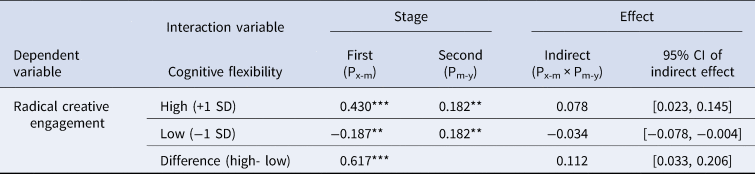

As depicted in Table 2, there was a positive relationship between employees' willingness to take risks and their engagement in radical creative activities (β = 0.182, p < 0.01). The bootstrapping analysis results, presented in Table 3, indicated that, when employees' cognitive flexibility was high, the indirect effect of stretch goals on employees' radical creative engagement through their willingness to take risks was significant and positive (indirect effect = 0.078, 95% CI = [0.023, 0.145]). However, when their cognitive flexibility was low, this indirect effect was significant and negative (indirect effect = −0.034, 95% CI = [−0.078, −0.004]). The difference between these indirect effects was also significant (difference = 0.112, 95% CI = [0.034, 0.205]). Therefore, both H2a and H2b were supported.

Table 3. Summary of conditional direct and indirect effects (Study 1)

Notes: N = 346. Px-m = stretch goals on willingness to take risks; Pm-y = willingness to take risks on radical creative engagement. Confidence intervals (CIs) are derived from the Monte Carlo simulation (with 20,000 repetitions). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion of Study 1 Findings

Study 1 found that the interaction of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility influenced employees' willingness to take risks, which then affected their radical creative engagement. For employees with high cognitive flexibility, stretch goals increased their willingness to assume risks and thus foster their radical creative engagement. For employees with low cognitive flexibility, stretch goals impaired their willingness to take risks and hence their radical creative engagement. Consequently, the findings in Study 1 lent support for our theoretical propositions.

However, Study 1 had certain limitations. First, cross-sectional study designs do not afford drawing firm conclusions regarding the causal ordering among studied variables. Second, the study examined only the effect of the interaction between stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on employees' radical creative engagement through their willingness to take risks. Therefore, whether this effect extended to employees' radical creativity (as hypothesized in H3a and H3b) was unclear. To address these limitations and test our model further, we conducted Study 2. Doing so conformed to LePine, Zhang, Crawford, and Rich's (Reference LePine, Zhang, Crawford and Rich2016) practice of replicating interaction patterns in a new sample.

Study 2

Sample and Procedure

Study 2 entailed a survey of full-time employees and their direct supervisors in the information technology industry in China. This industry was selected, owing to its high need for innovation. To recruit participants, we contacted senior managers or human resources managers across various companies through our established social networks. To minimize the potential for common method bias, we collected data at four different time points, per Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Research assistants conducted all data collection on-site during work hours. They also stressed the importance of confidentiality to participants prior to administering the survey. We preregistered this study at the following link: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UEZKG.

At Time 1, employees provided information on stretch goals and their cognitive flexibility, as well as on their demographic data. We received 704 completed questionnaires, an 88% response rate. At Time 2, approximately four weeks later, these 704 employees were asked to report their willingness to take risks. We received 612 completed questionnaires, an 87% response rate. At Time 3, approximately four weeks later, the remaining 612 employees were asked to record their radical creative engagement. We obtained 514 completed questionnaires, an 84% response rate. Finally, at Time 4, approximately four months later, we asked 155 direct supervisors to rate the radical creativity of their matched subordinates. After excluding incomplete or nonmatching questionnaires, the final sample consisted of 460 subordinates matched with 139 direct leaders.

Almost 44% of the subordinates were female, and 85.9% held at least one college degree. Their average age was 31.52 years (SDage = 7.54), and mean organizational tenure was 5.79 years (SDtenure = 5.50). Among the supervisor sample, 33.1% were female, and 72.7% held at least one college degree. Their average age was 38.47 years (SDage = 7.53), and mean organizational tenure was 8.91 years (SDtenure = 7.08).

We tested for potential nonrespondent bias and found no significant differences between Time 2 respondents and nonrespondents regarding their gender, age, education, organizational tenure, stretch goals, or cognitive flexibility. Similarly, there were no significant differences between Time 3 respondents and nonrespondents concerning their willingness to take risks. Additionally, we found no significant differences in radical creative engagement between employees who received a supervisor rating of radical creativity at Time 4 and those who did not.

Measures

Unless otherwise specified, all items were derived from established scales originally developed in English. As in Study 1, to translate the measures from English to Chinese, we followed Brislin's (Reference Brislin1986) translation and back-translation procedure. The scale anchors used were 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Stretch goals

(T1). Consistent with Study 1, we measured stretch goals using Zhang and Jia's (Reference Zhang and Jia2013) six-item scale. Cronbach's α was 0.929.

Cognitive flexibility

(T1). We assessed cognitive flexibility using the same 12-item scale used in Study 1. Cronbach's α was 0.916.

Willingness to take risks

We used the same items from Study 1 to assess willingness to take risks. Cronbach's α was 0.824.

Radical creative engagement

(T3). We measured radical creative engagement using the same 5-item scale used in Study 1. Cronbach's α was 0.867.

Radical creativity

(T4). We measured radical creativity using the 3-item scale from Madjar et al. (Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011). A sample item on radical creativity is, ‘This employee is a good source of highly creative ideas.’ Cronbach's α was 0.831.

Control variables

(T1). Consistent with Study 1, we included employees' gender (0 = male, 1 = female), organizational tenure (in years), and education (1 = college degree and lower to 4 = doctorate degree) as control variables in the analysis. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted by controlling for age instead of tenure or deleting all control variables, and the significance patterns remained unchanged.

Analytic Strategy

The analytical strategy of Study 2 was identical to that of Study 1.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA results showed that the five-factor model (i.e., stretch goals, willingness to take risks, cognitive flexibility, radical creative engagement, radical creativity) had an acceptable fit (χ² = 328.580; df = 160; CFI = 0.970; TLI = 0.965; RMSEA = 0.048; SRMR = 0.045) and a better fit than the alternative models. These results supported the distinctiveness of the measures used.

Common method variance check

Because all the variables except radical creativity were employee-based, we tested for common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). We added a latent common method factor to the same-source four-factor model and found that the addition of a latent factor improved the fit (Δχ²(17) = 97.032, p < 0.001). However, the change in all fit indices was less than 0.02 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2021b; Li et al., Reference Li, Ling and Liu2012), and the variance extracted by the common methods factor was only 0.103, far lower than the critical value of 0.5 (Dulac et al., Reference Dulac, Coyle-Shapiro, Henderson and Wayne2008; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black1998). Accordingly, common method variance was unlikely to pose a significant threat to the findings of this study.

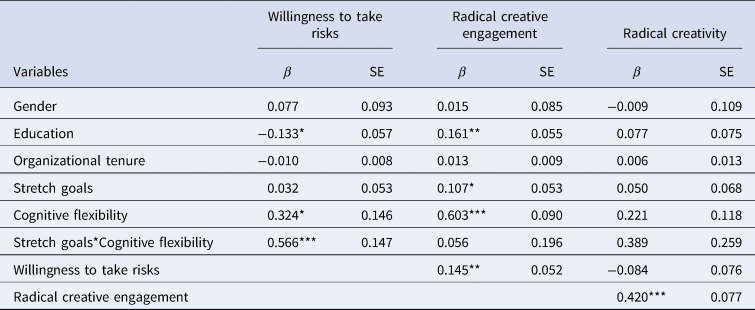

Hypothesis testing

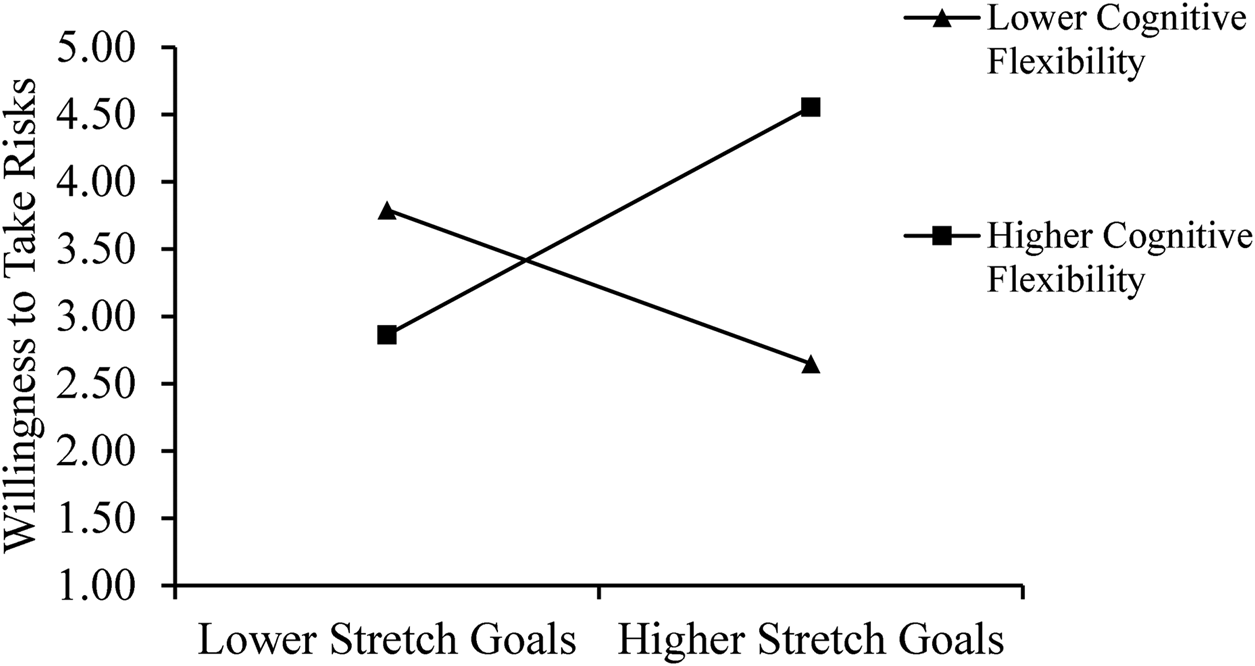

Shown in Table 4 are the descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables. The results of the path analysis are depicted in Table 5.

Table 4. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables (Study 2)

Notes: N = 460; all variables are unstandardized. Gender: 0 = male; 1 = female. Education: 1 = college degree or lower; 2 = bachelor's degree; 3 = master's degree; 4 = doctorate degree. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Table 5. Path analysis results (Study 2)

Notes: N = 460; β coefficients are unstandardized. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < .001.

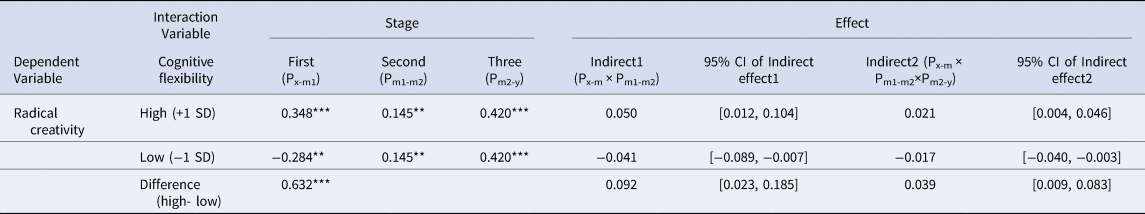

As revealed in Table 5, the interaction between stretch goals and cognitive flexibility significantly and positively influenced employees' willingness to take risks (β = 0.566, p < 0.001). To enhance understanding of this effect, we illustrated this interaction in Figure 3. Further analysis using simple slope tests indicated that, when employees' cognitive flexibility was high, the relationship between stretch goals and employees' willingness to take risks was positive and significant (β = 0.348, p < 0.001). However, when employees' cognitive flexibility was low, the relationship became significantly negative (β = −0.284, p < 0.01). Therefore, both H1a and H1b were supported.

Figure 3. Interactive effect of stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on employees' willingness to take risks (Study 2)

Furthermore, these results aligned with our expectations that employees' willingness to take risks positively influenced their radical creative engagement (β = 0.145, p < 0.01). As the bootstrapping analysis results in Table 6 demonstrated, when employees' cognitive flexibility was high, the indirect effect of stretch goals on radical creative engagement via willingness to take risks was significant and positive (indirect effect = 0.050, 95% CI = [0.012, 0.104]). However, when employees' cognitive flexibility was low, this effect became significant and negative (indirect effect = −0.041, 95% CI = [−0.089, −0.007]). The difference between these indirect effects was also significant (difference = 0.092, 95% CI = [0.023, 0.185]). As such, these findings supported H2a and H2b.

Table 6. Summary of conditional direct and indirect effects (Study 2)

Notes: N = 460. Px-m = stretch goals on willingness to take risks; Pm1-m2 = willingness to take risks on radical creative engagement; Pm2-y = radical creative engagement on radical creativity. Confidence intervals (CIs) are derived from the Monte Carlo simulation (with 20,000 repetitions). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < .001.

Finally, the analysis revealed that employees' radical creative engagement induced a positive effect on their radical creativity (β = 0.420, p < 0.01). Bootstrapping analysis exhibited a significant and positive indirect effect of stretch goals on employees' radical creativity through their willingness to take risks and radical creative engagement when their cognitive flexibility was high (indirect effect = 0.021, 95% CI = [0.004, 0.046]) (Table 6). However, when employees' cognitive flexibility was low, a significant and negative indirect effect was observed (indirect effect = −0.017, 95% CI = [−0.040, −0.003]). The difference between the two indirect effects was also significant (difference = 0.039, 95% CI = [0.009, 0.083]). These findings, therefore, supported H3a and H3b.

Discussion of Study 2 Findings

The results of Study 2 replicated as well as extended the findings of Study 1. They revealed that the indirect effect of stretch goals on employees' radical creative engagement was contingent on their cognitive flexibility. Moreover, this effect improved employees' radical creativity. Specifically, for employees with high levels of cognitive flexibility, stretch goals increased their willingness to take risks, which, in turn, improved their radical creative engagement and ultimately enhanced their radical creativity. For employees with low levels of cognitive flexibility, however, stretch goals decreased their willingness to take risks, which ultimately hindered their radical creative engagement and radical creativity.

General Discussion

Summary of Findings

We sought to clarify under what circumstances stretch goals can enhance or inhibit employees' willingness to take risks, thus influencing their radical creative engagement and radical creativity. Consistent evidence from two surveys shows that employees' cognitive flexibility plays a key role in the above relationship. For employees with high cognitive flexibility, we find a positive effect of stretch goals on their willingness to take risks and subsequent radical creative engagement and radical creativity. For employees with low cognitive flexibility, we observe a negative influence of stretch goals on their willingness to take risks and subsequent radical creative engagement and radical creativity. In sum, our findings indicate that employees with high cognitive flexibility can benefit more from stretch goals than employees with low cognitive flexibility. This is because of their differential willingness to assume risks and undertake radical creative engagement.

Theoretical Contributions

Our research offers several theoretical contributions. First, our overall contribution is that we have built and tested a conceptual model that uniquely integrates stretch goals with radical creativity. Although Ahmadi et al. (Reference Ahmadi, Jansen and Eggers2022) empirically investigated the impact of stretch goals on employee creativity, they overlooked differences in the extent to which ideas can improve the status quo. As Gilson and Madjar (Reference Gilson and Madjar2011) have argued, radical creativity and incremental creativity are related to different antecedents and processes. By uncovering the impact of stretch goals on employee radical creativity under different conditions (i.e., cognitive flexibility), as well as the specific attitude (i.e., willingness to take risks) and behavioral mechanism (i.e., radical creative engagement) involved, we provide enhanced nuanced understanding of the relationship between stretch goals and creativity.

Second, our study contributes to the literature on stretch goals by validating cognitive flexibility as a central catalyst for the relationship between stretch goals and employee' radical creativity. Scholars believe that not all employees respond to goals in a similar manner (Niven & Healy, Reference Niven and Healy2016). Although prior research has examined the impact of employees' previous success experiences, organizational tenure, organizational status, perspective taking, creative self-efficacy, a paradoxical mindset, and perceived organizational climate on the relationship between stretch goals and outcomes (Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Jansen and Eggers2022; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2019, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2020, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2021a, Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2021b; Zhang & Jia, Reference Zhang and Jia2013), our study confirmed that stretch goals either promote or inhibit employee radical creativity for employees with dissimilar levels of cognitive flexibility. We thus respond to Chen et al.'s (Reference Chen, Zhang and Jia2020) call to explore boundary conditions that render stretch goals either advantageous or detrimental.

Finally, our study introduces the concept of radical creative engagement, which is a distinctive aspect of our research. Though scholars have highlighted the distinction between creative process engagement and creativity (Zhang & Bartol, Reference Zhang and Bartol2010), they have also recognized that creativity can be categorized into radical creativity and incremental creativity (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011). However, there has been a lack of differentiation between radical creative engagement and incremental creative engagement. Radical creativity involves innovative ideas that can substantially reshape existing practices (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011; Madjar et al., Reference Madjar, Greenberg and Chen2011), and its associated activities are notably more complex compared to those concomitant with incremental creativity (Gong et al., Reference Gong, Wu, Song and Zhang2017). For instance, based on our research findings, when employees display a high willingness to take risks in generating new ideas, they tend to invest more in radical creative activities. However, owing to limited resources, employees' engagement in incremental creative activities may decrease. By introducing the concept of radical creative engagement, we set the stage for further exploration of the creative process.

Practical Implications

Our findings have several practical implications. First, we reveal that organizations can benefit or suffer from stretch goals vis-a-vis their effects on employees' radical creativity. Therefore, we recommend that organizations consider whether stretch goals are necessary and, if so, how to implement them to augment their positive impact. Second, when organizations consider applying stretch goals to motivate employees' engagement in radical activities, we encourage managers to foster employees' cognitive flexibility. Specific actions can be taken, such as presenting information in unstructured ways (Kim & Zhong, Reference Kim and Zhong2017) or encouraging employees to engage in counterstereotype exercises (Gocłowska, Crisp, & Labuschagne, Reference Gocłowska, Crisp and Labuschagne2013). Third, given that stretch goals can serve as signals and that signals can play a prominent role in organizations, managers can use strategies to create a context that values risk taking and leads employees to engage in radical creative actions.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This research has certain limitations. First, employees provided information on stretch goals, cognitive flexibility, willingness to take risks, and radical creative engagement. This raises the possibility that common method bias influenced our estimates. Although Siemsen, Roth, and Oliveira's (Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010) have averred that interaction effects are less likely to be due to common method variance and that the convergent results from our two studies alleviate this concern, we still recommend that future scholars adopt different methods and measures to test our hypothesis. In addition, although we tested the hypotheses using two different samples, our studies were not experimental (i.e., they were limited in their ability to assess causality). Therefore, future studies should assess our hypotheses with a more rigorous design.

Second, this study underscored the influence of a single receiver characteristic – namely, cognitive flexibility – on signal effectiveness. Although this variable is theoretically grounded in signaling theory, we acknowledge that other factors may affect receivers' interpretations of signals. For example, Wee, Derfler-Rozin, and Carson Marr (Reference Wee, Derfler-Rozin and Carson Marr2023) have argued that individuals of different status levels react differently to ‘task-based jolts'. Moreover, Jeong, Gong, and Zhong (Reference Jeong, Gong and Zhong2023) has proposed that implicit theories interact with employee-experienced crises (e.g., perhaps stretch goals) to impact employee creativity. Therefore, scholars should continue to explore critical variables that effectuate the effectiveness of stretch goals as signals.

Third, this study utilized employees' willingness to take risks and undertake radical creative engagement to explain the impact of the interaction between stretch goals and cognitive flexibility on employees' radical creativity. Although these mediators are theoretically sound, the role of other potential mediators should not be overlooked. For instance, amid a stretch goal, employees with high cognitive flexibility might experience positive affect (Sitkin et al., Reference Sitkin, See, Miller, Lawless and Carton2011), which could further enhance their radical creativity. Further research exploring other potential mediators is warranted.

Finally, we only examined the influence of stretch goals on employees' radical creativity. However, in achieving stretch goals, employees not only need to be extremely creative, but they also need to expend keen effort (Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Jansen and Eggers2022; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Giustiniano, Rego and Clegg2017; Zhang & Jia, Reference Zhang and Jia2013); such augmented effort is beneficial for employees' incremental creativity (Gilson & Madjar, Reference Gilson and Madjar2011). Thus, we encourage future research to explore the impact of stretch goals on employees' incremental creativity.

Conclusions

Drawing on signaling theory and creativity-related research, our results support a ripple effect whereby the interaction between stretch goals and cognitive flexibility predicts employees' willingness to take risks. Their willingness to take risks enhances employees' radical creative engagement, a prerequisite for their radical creativity. These findings hopefully advance understanding of stretch goals and help organizations achieve improved results amid fierce competition.

Data availability statement

In line with the current standards of methodological transparency, we have made the data, syntax, and results available at https://osf.io/ek4tb/

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grants 71832004, 72202096, 72302112) and the Key Project on Philosophy and Social Science Research of the Ministry of Education(Grant 21JZD056).

Zhiqiang Liu (zqliu@hust.edu.cn) is a Professor of Management at the Management School, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China. His current research interests include status competition in organizations, creativity, breakthrough innovation and LMX.

Yuping Xu (xuyuping2007hit@163.com) is currently pursuing a PhD degree in management at the School of Management, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Her research interests include leadership, creativity, and the impact of Artificial Intelligence on employees.

Ziyi Yu (1119579300@qq.com) is currently pursuing a master's degree in management at the School of Management, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Her research interests focus on goal management and creativity.

Bingqing Wu (wub@uwp.edu) is an Assistant Professor of Management at the University of Wisconsin, Parkside. She received her PhD in Business Administration from the University of Illinois, Chicago. Her research interests include leadership, creativity, and ambivalence.

Zijing Wang (tiewzj@163.com) is currently working toward a PhD degree in management with the School of Management, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Her research interests include leadership, organizational ethics, and creativity.